Abstract

Nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) was recently identified as the endogenous ligand for the opioid-receptor like (ORL1) receptor. Although the ORL1 receptor shows sequence homology with the opioid receptors, the nociceptin/ORL1 ligand–receptor system has very distinct pharmacological actions compared to the opioid receptor system. Recently, several small-molecule ORL1 receptor ligands were reported by pharmaceutical companies. Most of these ligands had close structural similarities with known neuroleptics and opiates. In this study, we screened several available neuroleptics and opiates for their binding affinity and functional activity at ORL1 and the opioid receptors. We also synthesized several analogs of known opiates with modified piperidine N-substituents in order to characterize the ORL1 receptor ligand binding pocket. Substitution with the large, lipophilic cyclooctylmethyl moiety increased ORL1 receptor affinity and decreased μ receptor affinity and efficacy in the fentanyl series of ligands but had a different effect in the oripavine class of opiate ligands. Our results indicate that opiates and neuroleptics may be good starting points for ORL1 receptor ligand design, and the selectivity may be modulated by appropriate structural modifications.

Keywords: Opioid receptor, ORL1 receptor, Nociceptin/orphanin FQ, Structure activity, [35S]GTPγS binding

1. Introduction

The discovery of the fourth member of the opioid receptor family, ORL1, has produced as many questions as answers with regard to its similarities and differences with the classical opioid receptors. Although activation of ORL1 with its endogenous ligand nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) was initially found to be nociceptive, subsequent experiments by a variety of labs have produced a somewhat bewildering array of in vivo actions. First, Grandy and colleagues demonstrated that nociceptin is not actually nociceptive but rather it blocks stress-induced analgesia brought on by the intracerebroventricular injection into mice (Mogil et al., 1996). It was then shown that nociceptin was not nociceptive when administered intrathecally, and in fact, it was modestly analgesic and potentiated morphine analgesia. It has also been reported to be an effective analgesic in a model of chronic pain (Yamamoto et al., 1997). In contrast, it has been shown to induce allodynia when injected into the spinal cord (Hara et al., 1997).

A great deal is known about the actions mediated by the opioid receptors, due in large part to the years of medicinal chemistry spent trying to design non-addicting analgesics. Extensive synthetic chemistry led to the original characterization of multiple opioid receptor subtypes. The availability of nonpeptide agents allows for peripheral administration of drugs and affords stability not present with peptides. Most important, the standard test to determine whether a compound is acting through opioid receptors is to determine whether the action is naloxone-reversible. One major drawback to the understanding of the myriad of actions mediated by the ORL1 receptor has been the lack of ligands specific for this receptor.

This situation was aided to some extent when we described the in vitro activity of high affinity hexapeptides with partial agonist activity at ORL1, peptides that had been identified from combinatorial libraries (Dooley et al., 1997). Unfortunately, probably because of very rapid degradation, these peptides have no activity in vivo (un-published observation). There was recently some excitement when Guerrini et al. (1998) identified a nociceptin analog, [Phe1 ψ(CH2–NH)Gly2 ]N/OFQ (1–13)NH2 ([Phe1 ψ]N/OFQ), that has antagonist activity in the mouse vas deferens. However, this compound turned out to have full agonist activity when tested in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with the human ORL1 receptor (Butour et al., 1998). It also acted similarly to nociceptin in a variety of in vivo assays, including its action with respect to analgesic activity (Grisel et al., 1998). However, Calo et al. (2000) later described a new peptide analog, [NPhe1 N/OFQ(1–13)NH2], which was a selective and competitive nociceptin antagonist, devoid of any residual agonist activity.

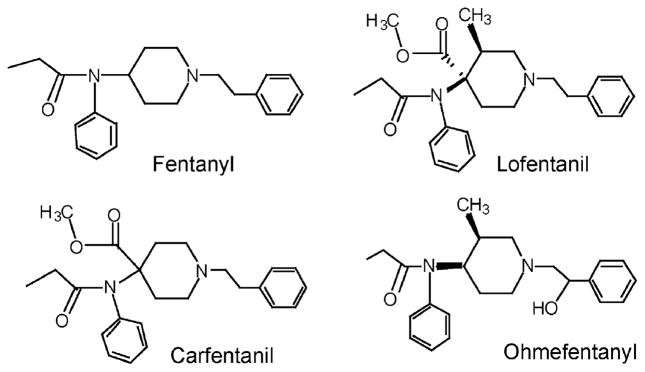

Several groups have examined available small-molecule opioids for binding at the ORL1 receptor in an effort to discover nonpeptide ORL1 receptor ligands. Naloxone benzoylhydrazone, a nonselective μ and κ receptor ligand, was reported to be a low potency competitive antagonist of nociceptin-induced effects (Bigoni et al., 1999). Kobayashi et al. (1997) found that the σ receptor ligands carbetapentane and rimcazole act as nonselective, low potency ORL1 receptor antagonists. Butour et al. (1997) tested the μ-selective opiate agonists lofentanil and fentanyl, both 4-anilidopiperidines, and etorphine, an oripavine derivative, for affinity at ORL1. Interestingly, lofentanil’s affinity for ORL1 is quite high (Ki = 24 nM) while that of fentanyl, a close structural analog of lofentanil, is very low (Ki > 1 μM), indicating that the ORL1 receptor differentiates well the 4-position substituents on the anilidopiperidine motif common to both drugs.

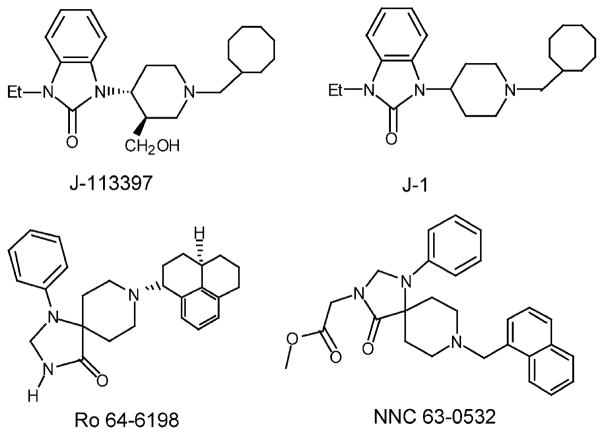

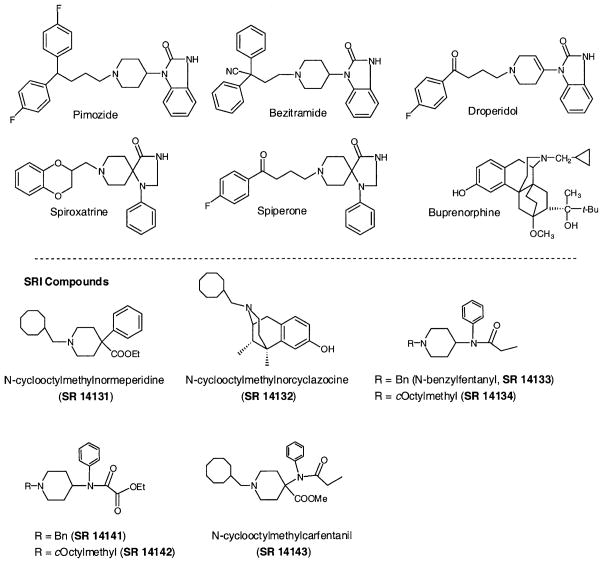

Recently, several potent and selective nonpeptide ORL1 receptor ligands have been reported by research groups from several pharmaceutical companies (Fig. 1). The group from Banyu described a high affinity and selective ORL1 receptor antagonist, 1-[(3R,4R)-1-cyclooctylmethyl-3-hydroxymethyl-4-piperidyl]-3-ethyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one (J-113397), obtained by extensive modification of a lead compound identified by screening (Kawamoto et al., 1999; Ozaki et al., 2000). High affinity agonists, on the other hand, were reported by Hoffman La Roche (Wichmann et al., 1999; Rover et al., 2000) and Novo Nordisk (Thomsen and Hohlweg, 2000). The Roche compound, (1S,3aS)-8-(2,3,3a,4,5,6-hexahydro-1H-phenalen-1-yl)-1-phenyl-1,3,8-triaza-spiro[4.5]decan-4-one (Ro 64-6198), is a potent agonist at ORL1(Ki = 0.39 nM) (Jenck et al., 2000) and has >100-fold selectivity over the opioid receptors. The Novo Nordisk compound, (8-naphthalen-1-ylmethyl-4-oxo-1-phenyl-1,3, 8-triaza-spiro[4.5]dec-3-yl)-acetic acid methyl ester (NNC 63-0532), has high affinity for ORL1 (Ki = 7.3 nM) but only 12-fold selectivity over opioid receptors. Interestingly, both these agonist ligands belong to the same chemical class, triazaspiro[4.5]-decanones, and differ mainly in their substituents on the piperidine nitrogen (Fig. 1). It is also interesting that all of the ORL1 receptor ligands above have a central piperidine core, bear close structural resemblance to well-known neuroleptics, and were obtained by structural modifications of such lead compounds. For example, NNC 63-0532 (Fig. 1) was obtained by structural modification of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist spiroxatrine (Fig. 2). The Roche compound is also structurally similar to spiroxatrine. The Banyu antagonist J-113397, on the other hand, bears structural resemblance to pimozide and the clinically used opioid analgesic bezitramide (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Structures of recently discovered ORL1 receptor ligands.

Fig. 2.

Structures of opiates and neuroleptics tested for ORL1 receptor affinity (top) and structures of SRI compounds based on ORL1 receptor-binding opiates (bottom).

In this study, we tested several known neuroleptics and opiates for their ORL receptor affinity. We also modified the piperidine nitrogen substituent in selected ligands in order to study the effect of these modifications on the binding affinity and selectivity of the ligands at ORL1. These studies will help to increase our understanding of the structural requirements for binding to the ORL1 receptor and help identify the variations in the receptor binding pocket that leads to the non-opioid nature of the ORL1 receptor.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Fentanyl, buprenorphine, meperidine, normeperidine, normetazocine, [D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly-ol5]-enkephalin (DAMGO), and D-Pen-D-Pen enkephalin (DPDPE) were obtained from the NIDA drug supply program. Pimozide, spiperone, haloperidol, droperidol, and spiroxatrine were purchased from RBI(Natick, MA). Nociceptin was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Belmont, CA). Bezitramide was the kind gift of Dr. James Woods (University of Michigan). [3H]nociceptin (120 Ci/mmol), [3H]DAMGO (51 Ci/mmol), and [3 H]DPDPE (42 Ci/mmol) were obtained from the NIDA drug supply program. [3 H] (+)-(5α,7α,8β)-N-{7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxas-piro [4.5]dec-8-yl}-benzeneacetamide ([3 H] U69593) (39.7 Ci/mmol) was purchased from NEN(Boston, MA).

The N-cyclooctylmethyl analogs of meperidine and cyclazocine (SR 14131 and SR 14132, respectively, Fig. 2), and buprenorphine were synthesized from normeperidine, normetazocine, and norbuprenorphine, respectively, via reductive amination with cyclooctylcarboxaldehyde. The fentanyl analogs were synthesized using literature methods (Van Deale et al., 1976), and the cycloctylmethyl analog of fentanyl was prepared by reductive amination of the N-dealkylated intermediate during the synthesis. The carfentanil analogs were synthesized according to the literature method for making carfentanil (Feldman and Brackeen, 1990). The Banyu compound 1-[1-cyclooctylmethyl-4-piperidyl]-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one (J-1, Fig. 1) was synthesized in our laboratory by the literature method (Kawamoto et al., 1999).

2.2. Cell culture

All receptors were in CHO cells transfected with human receptor cDNA. The cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum, in the presence of 0.4 mg/ml G418 and 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin, in 100-mm plastic culture dishes. For binding assays, the cells were scraped off the plate at confluence.

2.3. Receptor binding

Binding to cell membranes was conducted in a 96-well format, as described previously (Adapa and Toll, 1997). Cells were removed from the plates by scraping with a rubber policeman, homogenized in Tris buffer using a Polytron homogenizer, then centrifuged once and washed by an additional centrifugation at 27,000×g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and the suspension incubated with [3 H]nociceptin, [3 H]DAMGO, [3 H]DPDPE, or [3 H]U69593, for binding to ORL1, μ-, δ-, or κ-opioid receptors, respectively. The total volume of incubation was 1.0 ml and samples were incubated for 60–120 min at 25 °C. The amount of protein in the binding reaction varied from approximately 15 to 30 μg. The reaction was terminated by filtration using a Tomtec 96 harvester (Orange, CT) with glass-fiber filters. Bound radioactivity was counted on a Pharmacia Biotech beta-plate liquid scintillation counter (Piscataway, NJ) and expressed in counts per minute. IC50 values were determined using at least six concentrations of each peptide analog, and calculated using Graphpad/Prism (ISI, San Diego, CA). Ki values were determined by the method of Cheng and Prusoff (1973).

2.4. [35S]GTPγS binding

[35 S]GTPγS binding was conducted basically as described by Traynor and Nahorski (1995). Cells were scraped from tissue culture dishes into 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, then centrifuged at 500×g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in this buffer and homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 27,000×g for 15 min and the pellet resuspended in Buffer A, containing 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. The suspension was recentrifuged at 27,000×g and suspended once more in Buffer A. The pellet was sometimes frozen at −70 °C prior to use. For the binding assay, membranes (8–15 μg protein) were incubated with [35 S]GTPγS(50 pM), GDP(10 μM), and the appropriate compound, in a total volume of 1.0 ml, for 60 min at 25 °C. Samples were filtered over glass-fiber filters and counted as described for the binding assays. Statistical analysis was conducted using the program Prism.

3. Results

3.1. Binding affinities of ligands at ORL and opioid receptors

Upon publication by Kawamoto et al.(1999) of the first high affinity nonpeptide ORL1 receptor ligand, we noticed the similarity between their compound J-113397 and the clinically used analgesic bezitramide. We noticed further similarities to fentanyl analogs, from which bezitramide was originally developed, as well as other piperidine-containing compounds, primarily neuroleptics. This was consistent with the relatively high affinity found for the fentanyl analog lofentanil (Butour et al., 1997). Accordingly, we tested bezitramide and a variety of other commercially available piperidine-containing compounds. As seen in Table 1, the tested compounds had surprisingly low affinity for the ORL1 receptor. The highest affinity compound was the 5-HT receptor partial agonist spiroxatrine, with a Ki of 127 nM at the ORL1 receptor. This com-pound also has high affinity at the μ-opioid receptor (7.0 nM), slightly higher than that of the clinically used analgesic bezitramide (8.5 nM). We would expect this compound to have analgesic activity, not to mention addiction liability. The other compound found to have surprisingly high μ-receptor binding affinity is the Banyu ORL1 receptor antagonist J-1. In our hands, this compound has a Ki of 47 nM at μ-opioid receptors. By comparison, the Ki value we obtained at the ORL1 receptor was 8.6 nM, very similar to the value of Kawamoto et al.(1999).

Table 1.

Binding affinities at opioid receptors and ORL1

| Compound |

Ki (nM)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | δ | κ | ORL1 | |

| Bezitramide | 8.5±0.32 | >10,000 | 21.7±0.8 | >10,000 |

| Pimozide | 105±2.5 | 1491±305 | 822±223 | 216±101 |

| Spiroxatrine | 7.0±1.7 | >10,000 | 254±13 | 127±15 |

| Spiperone | nd | nd | nd | 1950 |

| Haloperidol | nd | nd | nd | >10,000 |

| Droperidol | nd | nd | nd | >10,000 |

| J-1 | 47.1±2.1 | 1368±53 | 162±3.6 | 8.6±1.9 |

| Cyclazocine | 0.1±0.01 | 0.8±0.05 | 0.1±0.02 | >10,000 |

| Meperidine | 143±66 | >10,000 | 327±50 | >10,000 |

| Buprenorphine | 1.5±0.8 | 4.5±0.04 | 0.8±0.05 | 112±22 |

| Fentanyl | 0.7±0.25 | 153±38 | 85±19 | >10,000 |

Binding was conducted to CHO cell membranes containing the appropriate human receptor, as described in Materials and methods. Values shown are Ki±S.D. for each compound, which derive from at least two individual experiments conducted in triplicate. Ki values were calculated using the Cheng Prusoff equation based upon the IC50 value that was determined using the program Prism.

Based upon the affinities of these compounds and the Banyu series of compounds described by Kawamoto et al. (1999), it appeared that the nitrogen N-1 substituent of the piperidine was an important determinant for affinity at ORL1 as well as at the opioid receptors. In particular, the N-cyclooctylmethyl moiety of J-113397 seemed to be optimum for ORL1 receptor binding. For this reason, we synthesized a series of N-cyclooctylmethyl derivatives of opioid compounds. These compounds were tested at ORL1 and the opioid receptors, and the values are shown in Table 2. None of the compounds produced high affinity at ORL1, but in some cases, the addition of the cyclooctylmethyl moiety increased affinity for ORL1 compared to the parent opiate. The most surprising exception is buprenorphine and its N-cyclooctylmethyl analog. Although the N-cyclopropylmethyl-containing buprenorphine is one of the highest affinity ORL1 receptor ligands among the opioid structures, N-cyclooctylmethylnorbuprenorphine showed basically no inhibition up to 10 μM. The addition of the cyclooctylmethyl moiety to these opiates had a variable action on their affinity for the opioid receptors—increasing the affinity of meperidine, decreasing the affinity of buprenorphine, and having a mixed action on fentanyl at the opioid receptors.

Table 2.

Binding affinities of novel compounds

| Compound |

Ki (nM)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | δ | κ | ORL1 | |

| Com-normeperidine a (SR14131) | 17.6±6.6 | 926±1.1 | 137±30 | 244±125 |

| Com-norcyclazocine (SR14132) | 158±25.6 | 1527±727 | 44.8±11.8 | >10,000 |

| Com-fentanyl (SR14134) | 4.6±0.4 | 1115±10 | 41.9±4.5 | 397±215 |

| Com-carfentanil (SR14143) | 0.28±0.02 | 128±5.6 | 2.0±0.04 | 152±59 |

| (SR14142) | 40.8±1.6 | 472±109 | 262±9.2 | 219±133 |

| Com-norbuprenorphine | 19.4±6.8 | 205±82 | 32±1.0 | >10,000 |

Binding and data analysis were performed as described in the legend of Table 1.

Com = cyclooctylmethyl.

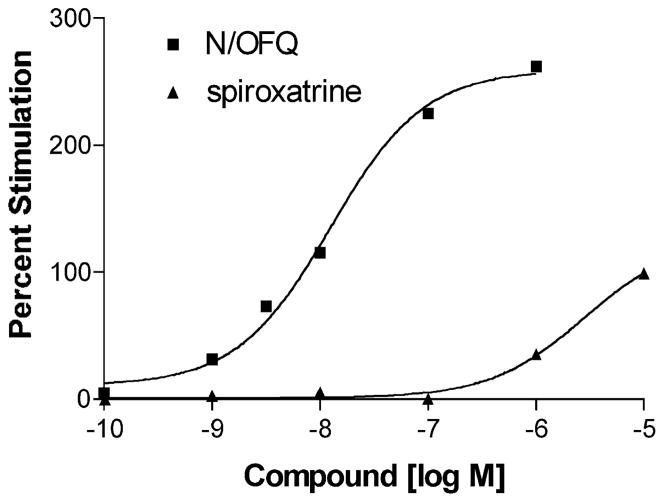

The highest affinity compounds were tested for functional activity at ORL1 by measuring stimulation of [35 S]GTPγS binding. As seen in Fig. 3, spiroxatrine was a weak agonist at ORL1, while the cyclooctylmethyl-containing opioid compounds were devoid of agonist activity. These compounds did display some antagonist activity at high concentrations (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding to hORL1 receptor-containing CHO cell membranes. The experiment was conducted as described in Materials and methods. Data are from a single experiment conducted in triplicate that was repeated with very similar results. Basal [35S]GTPγS binding was 71 fmol/mg and maximal stimulation with nociceptin was 240 fmol/mg protein. N-cyclooctylmethylfentanyl, N-cyclooctylmethylcarfentanil, and N-cyclooctylmethyl-normeperidine were tested concurrently and were found to produce no stimulation up to 10 μM.

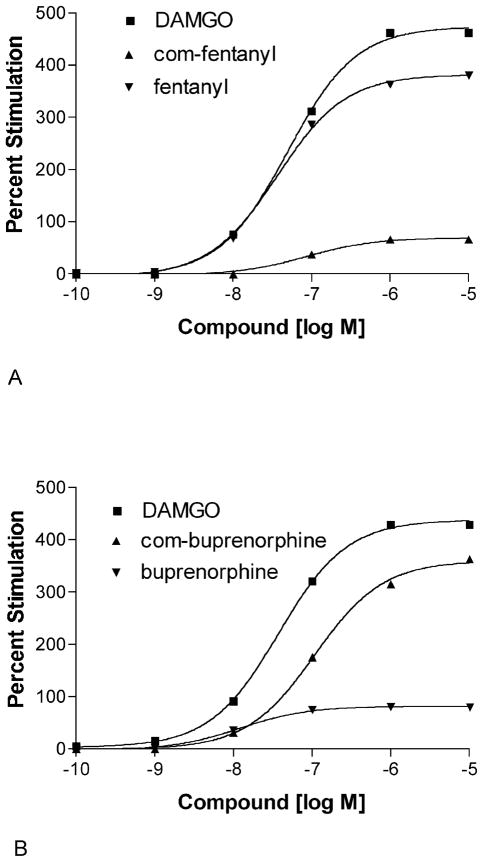

High affinity compounds were also tested for their ability to stimulate [35 S]GTPγS binding to μ-opioid containing cell membranes. As seen in Table 3, the clinically used analgesic bezitramide and the 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist spiroxatrine were partial to full agonists of moderate potency at the μ receptor. As expected, buprenorphine was found to be a potent partial agonist at μ receptors, while N-cyclooctylmethylnorbuprenorphine showed almost full agonist activity at the μ receptor. In contrast, in the fentanyl series, the cyclooctylmethyl moiety served to lower efficacy, leading to partial agonist activity at μ receptors (Fig. 4). Consistent with its moderate binding affinity at the μ receptor, the Banyu compound J-1 was also found to be a weak to moderate μ receptor partial agonist. This is in contrast to potent ORL1 receptor antagonist activity for this compound (Ke of 3.4 nM)(Gupta et al., submitted for publication).

Table 3.

Stimulation of GTPγS binding to μ-opioid receptors

| Compound | EC50 (nM) | Percent stimulation |

|---|---|---|

| DAMGO | 41.3±3 | 100 |

| Bezitramide | 216±25 | 88±5 |

| Spiroxatrine | 224±8 | 71±2 |

| Buprenorphine | 14.8±3 | 18±0.4 |

| Fentanyl | 52.7±14.3 | 74.5±9 |

| Com-fentanyl | 74.3±1 | 18±2.5 |

| Com-carfentanil | 2.5±1.0 | 33.6±5.0 |

| Com-norbuprenorphine | 303±190 | 88±2.8 |

| J-1 | 144±37 | 18±5.5 |

Binding was conducted to CHO cell membranes containing the human μ receptor, as described in Materials and methods. Values shown are EC50±S.D. for each compound, which derive from at least two individual experiments conducted in triplicate. EC50 values and maximal stimulation were determined using the program Prism. Percent stimulation was calculated as the percent maximal stimulation of the full agonist DAMGO, which was simultaneously run on each 96-well plate.

Fig. 4.

Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding to human μ receptor-containing CHO cell membranes. The experiment was conducted as described in Materials and methods. Data are from a single experiment conducted in triplicate that was repeated at least once with very similar results. (A) Stimulation with the full agonist DAMGO(■), N-cyclooctylmethyl(com) fentanyl (▲), or fentanyl (▼). (B) Stimulation with DAMGO (■), N-cyclooctylmethylnor(com)-buprenorphine(▲), or buprenorphine(▼). Basal [35S]GTPγS binding was 113 fmol/mg and maximal stimulation with DAMGO was 590 fmol/mg protein.

4. Discussion

The several small-molecule ORL1 receptor ligands recently reported in the literature, such as J-113397 (Kawamoto et al., 1999), Ro 64-6198 (Rover et al., 2000), and NNC 63-0532 (Thomsen and Hohlweg, 2000), were developed from screening leads that bear close structural resemblance to well-known piperidine-containing neuroleptics and opiate ligands. Their ORL1 affinity was primarily increased through modification of the N-1 piperidine substituent (Kawamoto et al., 1999; Rover et al., 2000; Thomsen and Hohlweg, 2000). Most of the known neuroleptics as well as the anilidopiperidine class of opiates possess the N-phenethyl, or a similar extended alkyl chain bearing an aromatic ring, at the N-1 of the piperidine (Figs. 2 and 5). Structural comparison of the reported ORL1 receptor ligands like J-113397, etc. and the compounds synthesized in this study (Fig. 2 and Table 2) to their parent opiates and neuroleptics provides hints on the shape and volume of the binding pocket in ORL1 and opioid receptors, particularly where the piperidine N-1 binds. Modification of the piperidine N-1 substituent produces significant changes in the affinity and selectivity of the ligands for ORL1 versus opioid receptors. Indeed, replacement of the N-benzyl substituent on the piperidine to a cyclooctylmethyl in the Banyu series of benzimidazolone compounds increased affinity for the ORL1 receptor and significantly decreased binding at the μ-, δ-, and κ-opioid receptors. (Kawamoto et al., 1999). In the synthetic analogs synthesized in this study, replacement of the small N-methyl group of meperidine, as well as the extended phenethyl group of fentanyl, with the lipophilic cyclooctylmethyl moiety increased the binding affinity at the ORL1 receptor and had a mixed effect on affinities at the opioid receptors. It therefore appears that for the anilidopiperidine class of ligands, the ORL1 receptor prefers and accepts large, voluminous lipophilic groups on the N-1 of the piperidine, close to the nitrogen. If the spirodecanone rings of spiroxatrine and spiperone (Fig. 2) are viewed as cyclized analogs of the 4-N-phenylpropanamide moiety of fentanyl, then it can be seen from Table 1 that spiroxatrine, with its large group closer to the piperidine ring, has higher affinity for ORL1 than spiperone, which contains the extended phenylbutanone group.

Fig. 5.

Structures of the anilidopiperidine class of opiate ligands.

On the other hand, for binding at the μ-opioid receptor, Subramanian et al.(2000) have shown that the fentanyl class of μ receptor ligands require the extended conformation of the N-phenethyl substituent and that increase in steric bulk or cyclization around the N-1 of the piperidine results in diminished μ affinity. This is further corroborated by the lack of μ affinity of analogs containing constrained or bicyclic N-1 substituents (Bagley et al., 1991). Therefore, anilidopiperidine-based ORL1 receptor ligands that have large lipophilic N-1 piperidine substituents will be inherently selective for ORL1 versus μ and other opioid receptors.

Topham et al. (1998) have constructed an active-site model of the ORL1 receptor liganded with nociceptin, based on the ORL1 amino acid sequence and the model of the bovine rhodopsin G-protein coupled receptor transmembrane domains. However, no docking for any small-molecule ORL1 receptor ligand has been carried out thus far, and it is not obvious from Topham’s model how a small-molecule ligand would orient itself into the ORL1 receptor active site, compared to the endogenous peptide ligand nociceptin. In the absence of a model of a small molecule in the active site, or a crystal structure of the small-molecule-bound ORL1 receptor, one must be very careful in evaluating structure–activity relationships among different classes of ORL1 receptor ligands, even those with very close structural similarities. Lofentanil is a close structural analog of fentanyl and possesses the extended N-phenethyl substituent on the piperidine, yet it is the most potent anilidopiperidine at the ORL1 receptor. Its IC50 for inhibition of [3 H]nociceptin binding to human ORL1 was reported to be 45 nM (Hawkinson et al., 2000). Lofentanil possesses the additional 4-ethoxycarbonyl group and the 3-methyl group on the piperidine (Fig. 5). It is tempting to hypothesize that this class of anilidopiperidines which possess the 4-alkoxycarbonyl group and the 3-alkyl substituent may bind slightly differently to ORL1 than the fentanyl series of compounds. Hawkinson et al.(2000) also found that ohmefentanyl (Fig. 5), which lacks the 4-ethoxycarbonyl group, is one order of magnitude less potent than lofentanil (IC50 = 520 nM) at ORL1. Carfen-tanil (Fig. 5), which possesses the 4-methoxycarbonyl group but lacks the 3-methyl group, has not yet been tested at ORL1. We synthesized the cyclooctylmethyl derivative of carfentanil (SR 14143) and found it to have fairly good affinity for ORL1 (Table 2).

We also looked at the effect of the same N-substituent variation on less flexible opioid structures. We observed that while the oripavine buprenorphine had good affinity for ORL1, replacing the N-cyclopropylmethyl group with the N-cyclooctylmethyl actually abolished ORL1 receptor binding affinity. The other rigid opiate structure tested followed a similar pattern. Substitution of the N-cyclopropylmethyl moiety of the benzomorphan, cyclazocine, with N-cyclooctylmethyl did not produce an increase in ORL1 receptor binding affinity. Several groups (Adapa and Toll, 1997; Butour et al., 1997; Hawkinson et al., 2000) have also tested other opiates such as etorphine, quadazocine, and zenazocine at ORL1 and found them to have sub-micromolar affinity at this receptor. Although these compounds have some structural similarity, leading to high μ-receptor binding affinity in each case, our results with structural modifications of buprenorphine and cyclazocine clearly show that these classes of opiates binds very differently to ORL1 than the anilidopiperidine class of compounds.

The presence of the cyclooctylmethyl moiety increased binding affinities at ORL1 for the anilidopiperidine and meperidine families. However, consistent with Kawamoto et al. (1999), this N-substituent reduces efficacy, as none of the cyclooctylmethyl fentanyl or meperidine analogs showed any agonist activity (Fig. 3). The introduction of the cyclooctylmethyl group onto the N-1 also had interesting actions on the efficacy of the compounds at the μ receptor. Exchange of the cyclopropylmethyl moiety of burprenorphine with cyclooctylmethyl lowered affinity at the μ receptor by one order of magnitude but also increased the efficacy substantially, producing essentially a full agonist. This is consistent with results in other fused-ring opiate families, in which substitution of the N–CH3 with cyclopropylmethyl or allyl substituents leads to antagonist activity while incorporation of a larger moiety, such as phenethyl, restores agonist activity (Harris and Pierson, 1964). As with buprenorphine, introduction of the cyclooctylmethyl into fentanyl (to make SR 14134) and carfentanil (to make SR14143) decreases their μ receptor affinity by one order of magnitude, but in contrast, it converts these compounds into low efficacy partial agonists, on the order of buprenorphine (Table 3). This suggests that the flexible anilidopiperidines and the bulky, lipophilic oripavines are oriented differently in the μ-receptor binding pocket. This also brings up the interesting possibility that increasing the lipophilic bulk close to the N-1 substituent in fentanyl may produce hitherto unknown fentanyl-based antagonists. Lower efficacy fentanyl analogs have been described, but these compounds maintained the normal N-phenethyl moiety (Bagley et al., 1989).

In conclusion, our study shows that opiates and neuroleptics can be good templates for ORL1 receptor ligands. For the anilidopiperidine class of ORL1 receptor ligands, it is clear that (1) there is a lipophilic pocket of defined geometry and depth at the ORL1 receptor into which the N-1 piperidine substituent of the ORL1 receptor ligand fits, and this substituent can therefore be optimized for maximum ORL1 affinity; and (2) there are specific binding elements in a well-defined spatial orientation in the ORL1 receptor in the vicinity of the 4-position of the piperidine, which interact with the 4-position substituents or heterocyclic rings and may be important for ORL1 affinity. The structure–activity relationships observed in our study as well as those recently reported in the literature shed light on the binding requirements and selectivity at ORL1, although a clear picture must await the resolution of a crystal structure of the ligand-bound ORL1 receptor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDA grant DA06682 to LT and NIDA grant DA07315 to JL.

References

- Adapa IP, Toll L. Relationship between binding affinity and functional activity of nociceptin/orphanin FQ. Neuropeptides. 1997;31:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(97)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley JR, Wynn RL, Rudo FG, Doorley BM, Spencer HK, Spaulding T. New 4-(heteroanilido)piperidines, structurally related to the pure opioid agonist fentanyl, with agonist and/or antagonist properties. J Med Chem. 1989;32:663–671. doi: 10.1021/jm00123a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley JR, Thomas SA, Rudo FG, Spencer HK, Doorley BM, Ossipov MH, Jerussi TP, Benvenga MJ, Spaulding T. New 1-(heterocyclylalkyl)-4-propionanilido-4-piperidinyl methyl ester and methylene methyl ether analgesics. J Med Chem. 1991;34:827–841. doi: 10.1021/jm00106a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigoni R, Calo G, Rizzi A, Mitri S, Regoli D. Naloxone benzoylhydrazone acts as a non selective nociceptin receptor antagonist. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1999;13:214s. [Google Scholar]

- Butour JL, Moisand C, Mazarguil H, Mollereau C, Meunier JC. Recognition and activation of the opioid receptor-like ORL 1 receptor by nociceptin, nociceptin analogs and opioids. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;321:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butour JL, Moisand C, Mollereau C, Meunier JC. [Phe1ψ(CH2–NH)Gly2]N/OFQ(1–13)NH2 is an agonist of the nociceptin (ORL1) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;349:R5–R6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo G, Guerrini R, Bigoni R, Rizzi A, Marzola G, Okawa H, Bianchi C, Lambert DG, Salvadori S, Regoli D. Characterization of [NPhe1]NC(1–13)NH2, a new selective nociceptin receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:1183–1193. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley CT, Spaeth CG, Craymer K, Adapa ID, Brandt SR, Houghten RA, Toll L. Binding and in vitro activities of peptides with high affinity for the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor, ORL1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PL, Brackeen MF. A novel route to the 4-anilido-4-(methoxycarbonyl) piperidine class of analgesics. J Org Chem. 1990;55:4207–4209. [Google Scholar]

- Grisel JE, Farrier DE, Wilson SG, Mogil JS. [Phe1ψ(CH2 – NH)Gly2 ]N/OFQ(1–13)NH2 acts as an agonist of the orphanin FQ/nociceptin receptor in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;357:R1–R3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Calo G, Rizzi A, Bigoni R, Bianchi C, Salvadori S, Regoli D. A new selective antagonist of the nociceptin receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:163–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara N, Minami T, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Sugimoto T, Sakai M, Onaka M, Mori H, Imanishi T, Shingu K, Ito S. Characterization of nociceptin hyperalgesia and allodynia in conscious mice. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:401–408. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LS, Pierson AK. Some narcotic antagonists in the benzomorphan series. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1964;143:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkinson JE, Acosta-Burruel M, Espitia SA. Opioid activity profiles indicate similarities between the nociceptin/orphanin FQ and opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;389:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenck F, Wichmann J, Dautzenberg FM, Moreau JL, Ouagazzal AM, Martin JR, Lundstrom K, Cesura AM, Poli SM, Rover S, Kolczewski S, Adam G, Kilpatrick G. A synthetic agonist at the orphanin FQ/nociceptin receptor ORL1: anxiolytic profile in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4938–4943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090514397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto H, Ozaki S, Itoh Y, Miyaji M, Arai S, Nakashima H, Kato T, Ohta H, Iwasawa Y. Discovery of the first potent and selective small molecule opioid receptor-like (ORL1) antagonist: 1-[(3 R,4 R)-1-cyclooctylmethyl-3-hydroxymethyl-4-piperidyl]-3-ethyl-1, 3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one (J-113397) J Med Chem. 1999;42:5061–5063. doi: 10.1021/jm990517p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Ikeda K, Togashi S, Itoh N, Kumanishi T. Effects of σ ligands on the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor coexpressed with the G-protein-activated K+ channel in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:986–987. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Grisel JE, Zhangs G, Belknap JK, Grandy DK. Functional antagonism of μ-, δ- and κ-opioid antinociception by orphanin FQ. Neurosci Lett. 1996;214:131–134. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki S, Kawamoto H, Itoh Y, Miyaji M, Azuma T, Ichikawa D, Nambu H, Iguchi T, Iwasawa Y, Ohta H. In vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization of J-113397, a potent and selective non-peptidyl ORL1 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;402:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rover S, Adam G, Cesura AM, Galley G, Jenck F, Monsma FJ, Jr, Wichmann J, Dautzenberg FM. High affinity, non-peptide agonists for the ORL1 (orphanin FQ/nociceptin) receptor. J Med Chem. 2000;43:1329–1338. doi: 10.1021/jm991129q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian G, Paterlini MG, Portoghese PS, Ferguson DM. Molecular docking reveals a novel binding site model for fentanyl at the μ-opioid receptor. J Med Chem. 2000;43:381–391. doi: 10.1021/jm9903702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen C, Hohlweg R. (8-Naphthalen-1-ylmethyl-4-oxo-1-phenyl-1,3,8-triaza-spiro[4.5]-dec-3-yl)-acetic acid methyl ester (NNC 63-0532) is a novel potent nociceptin receptor agonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:903–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topham CM, Mouledous L, Poda G, Maigret B, Meunier JC. Molecular modelling of the ORL1 receptor and its complex with nociceptin. Protein Eng. 1998;11:1163–1179. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.12.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR, Nahorski SR. Modulation by μ-opioid agonists of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate binding to membranes from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:848–854. doi: 10.1016/S0026-895X(25)08634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deale PGH, De Bruyn MFL, Boey JM, Sanczul S, Agten JTM, Janssen PA. Synthetic analgesics: N-(1-[2-Arylethyl]-4-substituted-4-piperidinyl)-N-arylalkanamides. Arzneim-Forsch Drug Res. 1976;26:1521–1529. doi: 10.1002/chin.197646236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann J, Adam G, Rover S, Cesura AM, Dautzenberg FM, Jenck F. 8-Acenaphthen-1-yl-1-phenyl-1,3,8-triaza-spiro[4.5]decan-4-one derivatives as orphanin FQ receptor agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2343–2348. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nozaki-Taguchi N, Kimura S. Effects of intrathecally administered nociceptin, an opioid receptor-like1(ORL1) receptor agonist, on the thermal hyperalgesia induced by unilateral constriction injury to the sciatic nerve in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1997;224:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]