Abstract

The norepinephrine (NE) transporter (NET) regulates synaptic NE availability for noradrenergic signaling in the brain and sympathetic nervous system. Although genetic variation leading to a loss of NET expression has been implicated in psychiatric and cardiovascular disorders, complete NET deficiency has not been found in people, limiting the utility of NET knockout mice as a model for genetically-driven NET dysfunction. Here, we investigate NET expression in NET heterozygous knockout male mice (NET+/−), demonstrating that they display an ~50% reduction in NET protein levels. Surprisingly, these mice display no significant deficit in NET activity, assessed in hippocampal and cortical synaptosomes. We found that this compensation in NET activity was due to enhanced activity of surface-resident transporters, as opposed to surface recruitment of NET protein or compensation through other transport mechanisms, including serotonin, dopamine or organic cation transporters. We hypothesize that loss of NET protein in the NET+/− mouse establishes an activated state of existing, surface NET proteins. NET+/− mice exhibit increased anxiety in the open field and light-dark box and display deficits in reversal learning in the Morris Water Maze. These data suggest recovery of near basal activity in NET+/− mice appears to be insufficient to limit anxiety responses or support cognitive performance that might involve noradrenergic neurotransmission. The NET+/− mice represent a unique model to study the loss and resultant compensatory changes in NET that may be relevant to behavior and physiology in human NET deficiency disorders.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, Morris water maze, tail suspension, light dark box, norepinephrine, transporter, knockout, genetic, heterozygote

INTRODUCTION

Norepinephrine (NE) pathways in the brain mediate attention, executive function, learning, memory, sleep, mood, and stress responses (Arnsten, 2009, Arnsten & Pliszka, 2011, Clayton et al., 2004). NE is implicated in disorders of cognition and mood, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, and anxiety (Beane & Marrocco, 2004, Leonard, 1997, Pliszka, 2005, Ressler & Nemeroff, 1999). The signaling duration and intensity of NE released at synapses are controlled through active transport into terminals by the presynaptically-localized Na+/Cl−-dependent NE transporter (NET) (Iversen, 1963, Iversen, 1971). Compounds with NET-blocking activity (tricyclic antidepressants, mixed action and NET-selective reuptake inhibitors (NSRIs)), are effective treatments for ADHD, anxiety and depression, although these compounds do not produce treatment response in all patients (Biederman & Spencer, 1999, Morilak & Frazer, 2004, Spencer et al., 1998).

The human NET gene is a member of the Na+/Cl−-dependent SLC6 transporter family that includes the dopamine and serotonin transporters (DAT and 5-HTT, respectively) (Hahn & Blakely, 2002, Hahn & Blakely, 2007, Nelson, 1998). A number of studies demonstrate association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the NET gene with ADHD (Bobb et al., 2005, Brookes et al., 2006, Kim et al., 2006, Kim et al., 2008, Sengupta et al., 2012, Xu et al., 2008, Xu et al., 2005), anxiety (Buttenschon et al., 2011, Gelernter et al., 2004), depression (Haenisch et al., 2009b, Hahn et al., 2008, Inoue et al., 2004, Ryu et al., 2004, Uher et al., 2009, Yoshida et al., 2004) and cardiovascular function (Hahn et al., 2003, Kohli et al., 2011, Shannon et al., 2000). Several polymorphisms associated with disease have been shown to impart functional consequences of decreased NET expression (Hahn et al., 2005, Hahn et al., 2003, Hahn et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2006). A SNP that codes for a nonfunctional NET protein variant, A457P, contributes to a familial form of the cardiovascular disorder, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) (Hahn et al., 2003, Shannon et al., 2000). A common NET SNP, -3081A/T, (rs28386840) acts as a transcriptional repressor in the NET gene promoter and is associated with ADHD, phenotypes in major depression and cardiovascular function (Hahn et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2006, Kohli et al., 2011). Additionally, a novel NET protein variant, T283M, identified in ADHD, results in diminished transport activity (Hahn et al., 2009).

In mice homozygous for the deletion of the NET gene (NET−/−), NE clearance is decreased and extracellular NE levels are elevated (Vizi et al., 2004, Xu et al., 2000). NET knockout mice exhibit psychostimulant supersensitivity, depression-related phenotypes, altered stress responding, decreased seizure activity, and changes in autonomic function (Ahern et al., 2006, Haenisch et al., 2009a, Kaminski et al., 2005, Keller et al., 2006, Keller et al., 2004, Xu et al., 2000). However, the consequences of partial NET impairment, such as that identified in human phenotypes, has remained largely unexplored in animal models. The present study utilizes NET heterozygous knockout mice (NET+/−) mice to investigate the consequences of partial NET disruption on NE reuptake and behavior.

METHODS

Animals

The NET knockout mouse line, generated by the laboratory of Dr. Marc Caron, was used in all experiments (Xu et al., 2000). These mice were originally generated using 129SvJ (now termed 129X1/SvJ; http://jaxmice.jax.org) mouse strain ES cells, and have been back-crossed for >10 generations onto the C57BL/6J strain background. Mice were bred and maintained in the Vanderbilt University animal facilities. To breed experimental animals, NET knockout line wild-type females and heterozygous males were mated to generate approximately equal numbers of wild-type and heterozygous offspring. To generate each cohort for assays, several breeding pairs were used to generate litters, and wild-type and heterozygous littermates from each of several litters were used in each cohort.

Mice were group-housed on 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle and given ad libitum access to food and water. Male mice greater than 8 weeks old at the start of experiments were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care Use Committee. Genotypes were determined by PCR using the following primers originally designed by the Caron laboratory: 5′-CTGCCATGAGAGAAAGAAGT-3′ (antisense common primer), 5′-TTGCCTGAGGAAAGGAAAGGC-3′ (sense primer to amplify wild-type NET allele) and 5′-TGGATGTGGAATGTGTGCGAG-3′ (sense primer to amplify NET knockout allele).

Synaptosome preparation

Mice were decapitated and brains dissected on ice. The cortical hemispheres were reflected from the brain after which the whole hippocampus is visible and was dissected. Then, frontal cortex was cut from each hemisphere at the border of the corpus callosum and extending 3.5 mm back from the rostral pole of the cortex. Brain tissues were homogenized in 9 ml of ice-cold buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 4.2 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) with a Teflon-glass homogenizer (Wheaton Science Products, Millville, NJ). After centrifugation of the homogenate at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Final P2 pellets were resuspended in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer (KRH; 120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgSO4 and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce).

Radiolabeled Transport Assay

[3H]NE transport was assayed in KRH buffer. Synaptosomes were preincubated for 10 min at 37°C, with or without 1 μM desipramine or 1 μM atomoxetine, to assess nonspecific accumulation, followed by the addition of 150 nM (single-point) or varying concentrations of [3H]NE (10 nM to 1 μM for kinetic analysis) (~45 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences). In experiments to determine transport of [3H]NE via the serotonin or dopamine transporter, some synaptosomes were also preincubated with 1 μM citalopram or 100 nM GBR12909, respectively. In experiments to determine the transport of [3H]NE through organic cation transporters (OCTs), synaptosomes were preincubated with 1 μM decynium-22 (D-22; Sigma Chemical Co. St, Louis, MO). To test the dependence of transport to external Na+, Na+ was replaced in the KRH assay buffer with equimolar N-methyl-D-glucamine. Transport assays were terminated by filtration of synaptosomes over 0.3% polyethylenimine-coated glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/B; Whatman) using a cell harvester (Brandel Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Accumulated [3H]NE was determined by scintillation counting (Beckman LS 6000).

Surface Biotinylation

To investigate the level of NET surface expression, biotinylation was performed on intact synaptosomes. Synaptosomes were incubated with cell impermeant sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotinamido) ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate- (sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin; 3.0 mg/ml; Pierce) for 30 min at 4°C, washed, quenched with 100 mM glycine, extracted in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, pH 7.4, with 250 μM PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μM pepstatin) for 30 min at 4°C and, and then incubated with a 50% slurry of immobilized streptavidin agarose beads (Pierce) for 30 min at room temperature. Beads were washed three times in RIPA buffer, and proteins bound to streptavidin beads were eluted in 1X Laemmli sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Total NET levels were determined from synaptosomes extracted in RIPA buffer. Samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as described for Western blot analyses.

Western Blots

Proteins were electrophoretically transferred overnight at 4°C to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were incubated in blocking solution (PBS, 2% Tween 20, 5% dry milk) for 1 h, followed by incubation with a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse NET at a dilution of 1:500 (NET05; Mab Technologies), and incubation with goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:5000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Antibody visualization was performed using Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagents (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Quantitation of band density was performed using ImageJ (NIH). Gel analyses were performed in replicates, and data are presented with representative blots and graphs of mean optical density from replicate experiments.

Behavior

Open field activity

Behavioral tests were performed in the following order; open field, light dark box, tail suspension, and Morris water maze. In all cases, at least 48 hours separated each behavioral test. For the open field test, mice were placed in open field activity chambers (29 × 29 × 20.5cm) that were housed inside environmental chambers (64 × 45 × 42) (Med Associates, Inc, St. Albans, VT). The environmental chambers remained closed for the duration of the test. The testing room was kept in normal lighting (250-300 lux) during testing. Testing was begun at approximately 9:00 am. The activity chambers were cleaned with MB-10 between each mouse. Mice were exposed to the open field for 1 hr. Movement and location were detected by the interruption of infrared beams by the body of the mouse and distance traveled calculated (Med Associates).

Light Dark Box

For the light-dark test, a black box (29 × 15 × 20.5 cm) insert was placed within one-half of the open field activity chambers (29 × 29 × 20.5 cm). The black box contains a single door for moving between the dark and light compartments. The activity chambers were housed inside environmental chambers (64 × 45 × 42 cm) (Med Associates). The doors of the environmental chambers remained closed for the duration of testing. The testing room was kept in normal lighting (250-300 lux) during testing. Testing was begun at approximately 9:00 am. Mice were brought into an anteroom 30 min before the start of testing. Mice were placed in the light side of the box at the start of the experiment and the test duration was 5 min. The activity chambers and inserts were cleaned with MB-10 between each mouse. Mouse movement and location were detected by the interruption of infrared beams by the body of the mouse and used to calculate time spent in the light and dark compartments (Med Associates).

Tail Suspension

Mice were brought into an anteroom 30 min prior to testing. For the tail suspension test, mice were suspended for seven minutes by the tail from a vertical aluminum bar (bar size: 11.5 × 2.3 cm) attached to the top of a box-like enclosure (33 × 33 × 32cm) open on the front side (Med Associates). Mice were attached to the bar by tape placed ~1.5 cm from the tip of the tail. Mice were monitored visually throughout the test to ensure they did not tail climb. The level and duration of force placed on the bar by the mouse was measured, with a force level below the lower threshold being counted as immobilization (Med Associates). The settings used were: lower threshold of 7, upper threshold of 20, gain of 8, and resolution of 220 ms. Boxes were cleaned with MB-10 between each test. The testing room was kept in normal lighting (250-300 lux) during the test. Testing was begun at approximately 9:00 am.

Morris Water Maze

The Morris Water Maze task was performed using a circular pool with a diameter of 106 cm and sides 40.5 cm high containing a submerged platform 10 cm in diameter. Water in the pool was made opaque using non-toxic tempera paint. Mice were placed in the pool with their heads facing the sides of the pool at 1 of 4 locations for a given trial. The mice were given 60 seconds to find the platform and if they did not find it in during the allotted time, they were placed on the platform for 15 seconds prior to their removal from the pool. Mice underwent 4 trials per day, and were placed at a different location in the pool at the start of each trial. Trial days continued until the latency of the mice to find the platform reached an asymptote or their time to reach the platform was 10 seconds or less. One day following completion of the acquisition phase, a probe trial was performed in which the platform was removed for the duration of one 60 second trial. The time mice spent in the quadrant where the platform was located during the acquisition phase (target) was measured. One day following the probe trial, the reversal phase was performed, in which the platform was moved to the quadrant opposite to the acquisition phase position. Trials were performed exactly as described for the acquisition phase. Trial days continued until the latency of the mice to find the platform reached an asymptote or their time to reach the platform was 10 seconds or less. One day following the reversal phase, another probe trial was performed. A camera positioned directly above the pool videotaped the sessions. ANY-maze software was used to define the quadrants within the pool and automatically collect data including time spent in each quadrant, duration of trial, and swim speed (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL).

Statistical Analyses

Data from all experiments were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc testing, or two-tailed t-tests, as appropriate for experimental design (SPSS20, Prism). P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Open field activity was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and thigmotaxis was compared using t-test. Light-dark test results were analyzed using t-test. Water maze data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA repeated measures followed by post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons to compare genotypes on different days. Single point transport and Western blot assays were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA comparing brain region between genotypes. Transport experiments to determine saturation kinetics were analyzed using nonlinear regression analysis according to a single-site hyperbolic model to calculate KM and VMAX values (Prism version 5; GraphPad Software Inc.). One or two-way ANOVA was used to compare derived VMAX or KM values. Single-point transport assays testing the effects of D-22 or Na+-dependency were analyzed by two-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

Decreased NET expression, but not NE transport, In NET+/− mice

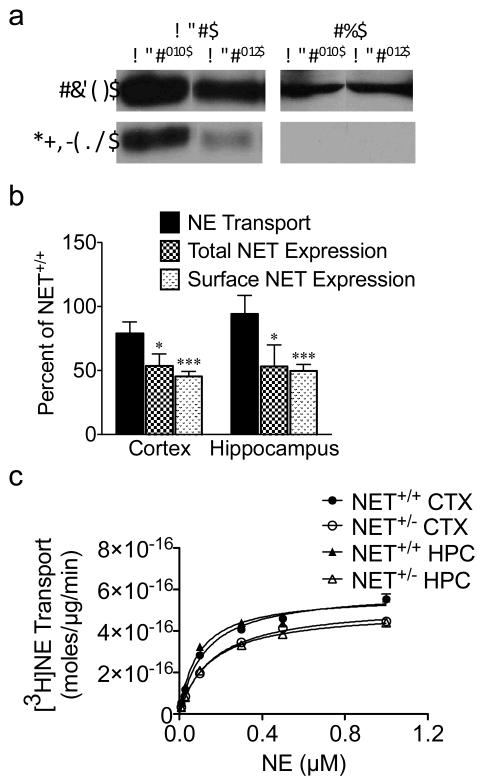

In order to evaluate NET function in the NET+/− mouse, NET expression levels and transport activity were determined in cortex (CTX) and hippocampus (HPC), brain regions of noradrenergic neuronal innervation. Cortical and hippocampal synaptosomes were subjected to biotinylation with the membrane-impermeant biotinylating reagent, sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, to identify NET on the synaptosome plasma membrane and in total protein lysates. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) was used as a control for surface labeling in the biotinylation assay. Whereas NET was expressed in total and surface fractions, TH signal was observed solely in total fractions, indicating selective labeling of surface proteins in the biotinylation assay (Fig. 1a). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant genotype effect for both total (F(1,8)=6.215) and surface (F(1,8)=174.8) NET protein (Fig 1a,b). HPC and CTX NET protein levels were decreased by approximately 50% in both total (p<0.05) and surface fractions (P<0.001) of NET+/− mice (N=3; Fig 1a,b). Transport measured in synaptosomes using 150 nM [3H]NE decreased by only ~15%, which was not significant (F(1,16)=0.385; N=5; Fig 1b). Saturation kinetic analyses were then performed to determine more fully any possible changes in NET activity (Fig. 1c). Data were well fit to a single site transport function. The VMAX values for NET+/− mice were decreased ~15%, and not significantly different from NET+/+ VMAX values. VMAX values in 10−16 mol/μg/min: NET+/+ CTX, 6.3±1.3; NET+/− CTX, 5.5±1.1; NET+/+ HPC, 5.9±0.8; NET+/− HPC, 4.9±0.8. F(3,12)=0.3315; Fig. 1c). There were no differences between NET+/+ vs. NET+/− for KM for NE transport in CTX or HPC. KM values were: NET+/+ CTX, 140±50 nM; NET+/− CTX, 175±47 nM; NET+/+ HPC, 100±22 nM; NET+/− HPC, 142±20 nM (F(3,12)=0.682).

Figure 1.

NET expression and activity in synaptosomes from NET+/+ versus NET+/− mice. Synaptosomes were subjected to surface biotinylation (sulfo-NHS-SS biotin) followed by immunoisolation. Total and surface NET and TH levels were analyzed on Western blot (a,b). In the same sample, [3H]NE transport was measured in a ten minute transport assay at 37°C using 150 nM [3H]NE. Data are expressed as the mean percent ± SEM of NET+/+ results for each assay and brain region. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, N=3 (b). Saturation kinetics of [3H]NE transport. Synaptosomes were incubated in 10 nM-1 μM [3H]NE for 10 min at 37°C (c). TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; CTX, cortex; HPC, hippocampus.

Lack of compensation of NE transport through other transporters in NET+/− mice

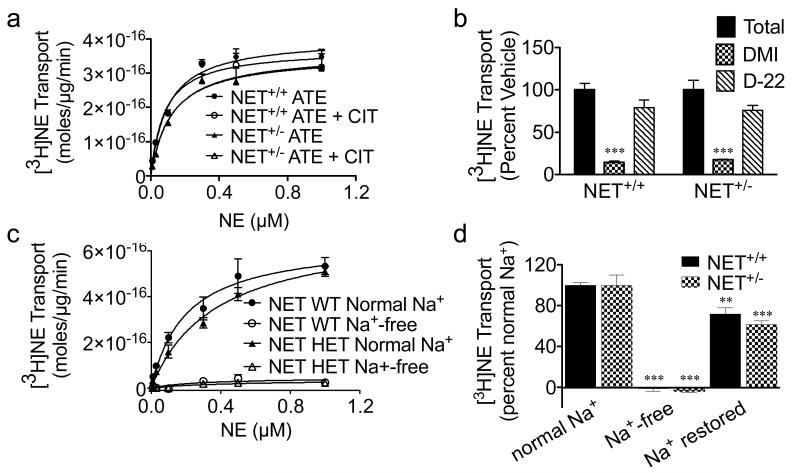

We next sought to determine if the discrepancy between uptake and protein levels in NET+/− mice was due to a change in NET-mediated transport versus other means of NE uptake. Studies have suggested that 5-HTT and DAT binding sites are increased in NET−/− mice, and that NE is accumulated in HPC via 5-HTT in NET−/− mice, suggesting transport of NE through these other carriers might be prominent in NET−/− mice (Solich et al., 2011, Vizi et al., 2004). Thus, we tested if NE is transported through the other monoamine transporters in NET+/− mice. NE transport was measured in hippocampal synaptosomes in the presence of atomoxetine (selective NET inhibitor), citalopram (selective 5-HTT inhibitor), or both in combination. Citalopram alone produced minimal inhibition of [3H]NE transport in both NET+/+ and NET+/− mice that was not different between genotypes (data not shown). Compared to atomoxetine alone, atomoxetine plus citalopram did not affect the VMAX for NE transport in either NET+/+ mice (3.7±0.4 vs. 3.8±0.4 × 10−16 mol/μg/min) or NET+/− mice (3.6±0.6 vs. 3.7±0.6 × 10−16 mol/μg/min) (F(3,8=0.0255; N=3; Fig. 2a). KM was also unaffected (F(3,8)=0.8524, N=3). Cortical synaptosomes also did not demonstrate NE transport through 5-HTT (data not shown). The DAT-selective inhibitor, GBR-12909, was also without effect on NE transport in atomoxetine-treated synaptosomes (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Specificity of NET-mediated transport in brain synaptosomes. Saturation kinetics of [3H]NE transport in the presence of either 1 μM atomoxetine (ATE) or 1 μM atomoxetine plus 1 μM citalopram (CIT). Synaptosomes were incubated in 10 nM-1 μM [3H]NE for 10 min at 37°C (N=3) (a). [3H]NE transport in the presence of 1 μM desipramine or 1 μM decynium-22 (D-22) followed by a 10 min incubation in 150 nM [3H]NE at 37°C. ***p < 0.001, N=4 (b). Saturation kinetics of of [3H]NE transport in the presence or absence of Na+. Synaptosomes were incubated in 10 nM-1 μM [3H]NE for 10 min at 37°C (c). [3H]NE transport in normal, Na+-free, and normal Na+ following Na+-free conditions. Synaptosomes were incubated in 150 nM [3H]NE for 10 min at 37°C. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, N=4 (d).

Other candidates for an alternate means of NE transport in the brain are members of the organic cation transporter family (OCTs). In contrast to NET and other SLC6 family members, OCTs are sodium-independent transporters and have a much lower affinity for monoamines than the SLC6 family (Amphoux et al., 2006, Koepsell et al., 2007). However, in 5-HTT knockout mice, OCT3 is upregulated and mediates reuptake of 5-HT in the hippocampus (Baganz et al., 2008). Thus, we tested whether a similar mechanism would be invoked under conditions of NET deficiency in the NET+/− mice. First, we used an inhibitor of OCTs, decynium-22 (D-22) (Schomig et al., 1993), to determine the contribution of OCTs to hippocampal NE transport in NET+/+ versus NET+/− mice. There was a significant effect of drug (F(2,18)=74.27; N=4). This was due to the effect of desipramine to block >80% of transport in both NET+/+ and NET+/− mice (p < 0.001; N=4; Fig. 2b). However, D-22 had no significant effect to block transport in either genotype. Thus, there was no effect of genotype on the response to either desipramine or D-22 (F(1,18)=0.00; N=4; Fig. 2b). This data supports that OCT activity is not contributing to the observed NE transport in the HPC of NET+/− mice. D-22 may have other targets in addition to blocking OCTs that may have contributed to its smaller, non-significant trends to decrease transport. Therefore, we also determined the contribution of OCTs to NE transport by performing transport assays in the absence and presence of sodium, as OCTs are Na+-independent transporters (Koepsell et al., 2007). In the absence of Na+, transport was nearly abolished in both NET+/+ and NET+/− mice. The lack of transport in the Na+-free condition prevented curve-fitting. Thus, transport levels measured in 1 μM NE were used to compare between groups. Both NET+/+ and NET+/− mice demonstrated significantly reduced NE transport compared to their normal Na+ controls, approximately 2.5% of normal transport levels (F(3.8)=31.39; N=3; p < 0.001; Fig. 2c). In order to account for any effect of Na+-free conditions to impair synaptosomes, we restored full Na+ to synaptosomes that had been previously incubated in Na+-free media and performed [3H]NE transport assays using 150 nM [3H]NE. As we observed previously, transport was abolished in Na+-free media (F2,18)=199.4); N=4; Fig. 2d). This effect was observed in both NET+/+ (p<0.001) and NET+/− (p<0.001) mice. Furthermore, the majority of NET transport activity was restored by switching back to Na+-containing assay buffer, demonstrating that synaptosomes were still viable and capable of transport in the Na+-free media (Fig. 2d). There was no effect of genotype on the ability of Na+-free media to inhibit [3H]NE transport (F(1,18)=0.8506. The same results were obtained using cortical synaptosomes in the Na+-free experiments (data not shown). In summary, a Na+-independent OCT transporter does not appear to account for the normalized transport in NET+/− mice. Taken together, these data indicate that NET+/− mice have more NET activity relative to transporter expression level compared to NET+/+ mice, supporting near normal levels of transport.

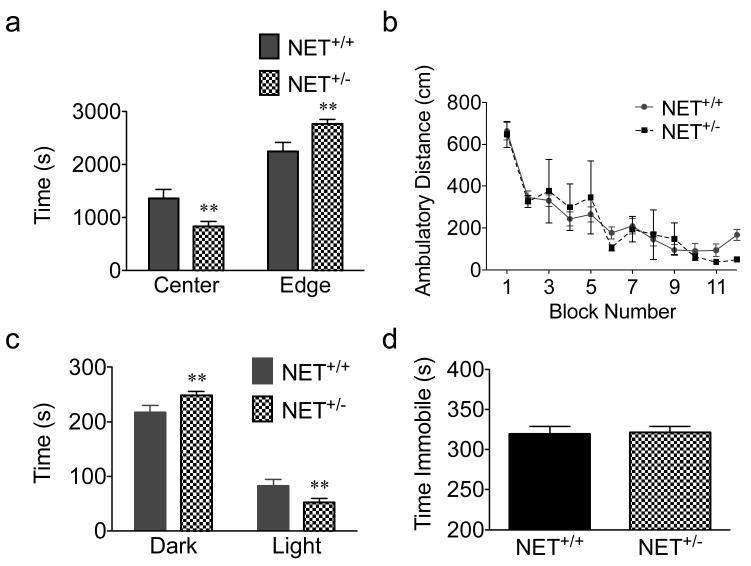

NET+/− mice have anxiety like behaviors and cognitive deficits

We next examined whether altered regulation of NET expression and activity in the NET+/− mice influences behavior on tasks that probe anxiety/depression-related behaviors and cognitive function. In the open-field test, mice were exposed to novel, open field chambers for one hour. Compared to NET+/+ mice, NET+/− mice spent less time in the center of the field and more time in the peripheral zone, consistent with an anxiety-phenotype (p < 0.01; N=14-20; Fig 3a). We detected no difference in the total distance traveled, supporting a lack of an effect on motor activity (F(1,384)=0.0288; Fig. 3b). Next, we tested mice in another task to measure anxious behavior, the light-dark box. Both NET+/+ and NET+/− mice spent more time in the dark side, as typically observed in this task. However, NET+/− spent significantly more time in the dark and less time in the light compartments compared to NET+/+ mice (p < 0.01; Fig. 3c). Mice were also tested in the tail suspension test, in which mice were suspended by their tails for 7 minutes and struggling versus immobility were measured. The tail suspension test is sensitive to antidepressants, which increase the amount of time spent struggling, behavior that is considered to be reduced despair. NET+/− mice did not differ from NET+/+ mice in total time spent immobile (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Anxiety/depression phenotypes in NET+/+ versus NET+/− mice. Open field exploration during a 1 h trial (a,b) Time spent in the center versus periphery of the open field. Data are expressed as mean time in s ± SEM for each area of the field. **p < 0.01, N=14-20 (a). Distance traveled in the open field displayed in 5 min blocks (N=14-20) (b). Time spent in the light vs. dark in a 5 min light-dark test. Data are expressed as mean time in s ± SEM for each compartment. **p < 0.01, N=21-29 (c). Immobility during a 7 min-duration tail suspension test. N=14-20 (d).

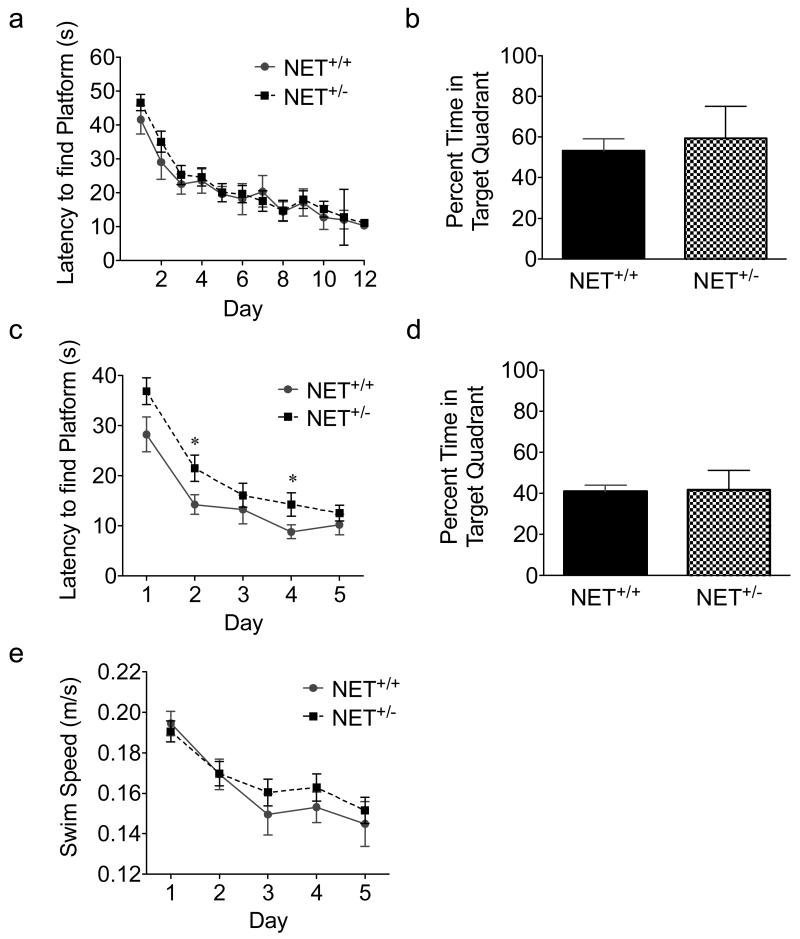

We next examined the performance of NET+/− mice in the Morris water maze (MWM). NE mediates learning acquisition and retention in the MWM, and improves reversal learning of a new platform location in this task (Bjorklund et al., 2000, Decker & Mcgaugh, 1989, Hatfield & Mcgaugh, 1999, Roozendaal et al., 2004). Stress can impair reversal learning in the MWM (Cerqueira et al., 2005, Quan et al., 2011, Sousa et al., 2000). These data, together with the observed anxiety phenotype, suggested MWM performance might also be affected in NET+/− mice. In the MWM, mice were trained to find a hidden platform in a pool of opaque water. During the acquisition phase, mice were exposed to the water maze for 60 second trials, 4 times per day until the latencies to find the platform reached asymptote or were 10 seconds or less. During acquisition, there was no difference between NET+/+ and NET+/− in latency to find the platform (F(1,276)=0.9422; N=8-20; Fig. 4a). There was also no difference between genotypes in a probe trial performed one day following acquisition for time spent in the target quadrant (Fig. 4b). We next exposed the mice to a reversal learning task in the MWM in which the location of the platform was moved to a different quadrant of the pool. There was an overall genotype effect, with NET+/− mice demonstrating increased latencies to find the platform compared to NET+/+ mice (F(1,130)=8.590; Fig. 4c). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences in time to find the platform on days 2 and 4 (P<0.05; Fig 4c). There was no difference between genotypes in the probe trial performed one day following the reversal phase (Fig. 4d). We measured swim speed to determine if changes in motor activity accounted for the increased time it took NET+/− mice to find the platform. There were no differences in swim speed at any of the time points (F(1,135)=0.9289; Fig. 4e).

Figure 4.

Performance in the Morris water maze. For the acquisition and reversal phases, each mouse underwent four trials per day and the mean per mouse for a measure was used to calculate the mean ± SEM for the NET+/+ or NET+/− group on that day (a,c,e). Latency to find the platform during the acquisition (a) and reversal (c) phases of the task. *p < 0.05, N=8-20. Probe trials were performed once for 60 seconds on the days following the acquisition (b) and reversal (d) phases and are expressed as percent time spent in the target quadrant versus other quadrants ± SEM. Swim speed during the reversal phase of mice shown in c (e).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to our knowledge to evaluate NET protein expression or activity in the NET+/− mouse. A number of human polymorphisms resulting in decreased, but not completely abolished, NET activity have been identified and associated with disease, underscoring the importance of understanding genetically-induced NET deficiency (Hahn et al., 2005, Hahn et al., 2003, Hahn et al., 2009, Halushka et al., 1999, Kim et al., 2006, Shannon et al., 2000). In the present study, we observed that although transporter levels were reduced by approximately half in NET+/− mice, transport rates were only reduced by ~15%, a value that did not reach significance. Interestingly, these results differ from our recent findings using a knockin mouse of a NET genetic variant (A457P) identified in a familial cardiovascular disorder. In that study, heterozygous knockin mice, containing one wild-type NET allele and one A457P allele, demonstrated significant deficits in NE transport that might involve a dominant negative effect of the A457P allele (Hahn et al., 2003, Shirey-Rice et al., 2013).

The present data support that the enhanced NET activity is mediated via NET. Given evidence of NE transport through other transporters, we endeavored to explore other potential mechanisms of NE transport in NET+/− mice. For example, Vizi et al. reported citalopram-sensitive NE transport in the NET−/− mouse (Vizi et al., 2004), whereas studies support that DAT is not a likely compensatory mechanism for NE uptake (Moron et al., 2002). Neither 5-HTT nor DAT provided a mechanism for enhanced NE transport in the NET+/− mice. Organic cation transporters (OCTs; SLC22) are also capable of transporting NE, although at much lower affinities than NET, with KMs approximately 1000-fold higher than the NE concentrations used in the present experiments (Amphoux et al., 2006). Using both pharmacological inhibition and Na+-free conditions to inhibit OCT activity, we did not observe OCT-mediated NE transport. We conclude that NET is responsible for the observed NE transport in the NET+/− mice. This suggests that the plasma membrane harbors “spare” NETs or NETs increase their intrinsic activity in NET+/− mice.

Changes in firing rate, adrenergic receptor expression and sensitivities, extracellular levels of substrate, and other cellular signaling mechanisms, can elicit upregulated NET activity (Bergstrom & Kellar, 1979, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska et al., 2006, Gilsbach et al., 2006, Grant & Weiss, 2001, Invernizzi & Garattini, 2004, Nestler et al., 1990, Parini et al., 2005, Vizi et al., 2004, Xu et al., 2000). For example, extracellular levels of substrate are known to stabilize the expression of monoamine transporters at the cell surface (Brenner et al., 2007, Ramamoorthy & Blakely, 1999, Weinshenker et al., 2002, Whitworth et al., 2002, Whitworth & Quick, 2001). Protein kinase C (PKC) and protein kinase B (Akt) down-regulate NET, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) increases NET activity (Apparsundaram et al., 1998a, Apparsundaram et al., 1998b, Apparsundaram et al., 2001, Jayanthi et al., 2004, Robertson et al., 2010). Trafficking-independent regulation of transporter activity, like that observed in the present study, occurs in response to kinase signaling mechanisms and changes in interacting protein complexes (Apparsundaram et al., 2001, Jayanthi et al., 2005, Sung et al., 2003, Zhu et al., 2005, Zhu et al., 2004) For example, p38MAPK increases NET activity and the association of NET in a complex with Syntaxin 1A decreases NET activity, in both cases independently of a change in surface transporter number (Apparsundaram et al., 2001, Sung et al., 2003). Adaptations in multiple cellular mechanisms may serve to set a new level of NET activity in the remaining transporters in the NET+/− mouse.

Findings from studies of heterozygous DAT and 5-HTT knockout mice might elucidate the present results in NET+/− mice. DAT+/− mice demonstrate a 50% decrease in DA clearance measured with voltammetry and a similar reduction in transporter density (Jones et al., 1998). Initial studies of 5-HTT+/− mice demonstrated protein expression to be 50% of WT protein levels, without a change in transport in synaptosomes (Bengel et al., 1998). However, measuring 5-HT clearance in a synaptosomal preparation using chronoamperometry, a 60% reduction in 5-HT clearance was observed in 5-HTT+/− compared with 5-HTT+/+ mice (Perez & Andrews, 2005). Furthermore, in a study using in vivo high speed chronoamperometry, it was demonstrated that clearance was not different in 5-HTT+/− compared to 5-HTT+/+ mice when low concentrations of 5-HT were locally pressure ejected into the hippocampus, but that higher concentrations of 5-HT (1 μM) produced a 50% reduction of 5-HT clearance (Montanez et al., 2003). These data suggest that 5-HT clearance in 5-HTT+/− mice demonstrates a compensatory increase in transport apparent at lower, but not higher, concentrations of 5-HT. Such situation-dependent manifestations of transport deficits versus compensation may provide one potential explanation of the negligible effects on NE transport, yet emergent behavioral phenotypes, observed in NET+/− mice in the present study.

The present results demonstrate that NET+/− mice exhibit several behavioral phenotypes, in both affective and cognitive dimensions. NET+/− mice demonstrated increased anxiety compared to NET+/+ mice in the open field and light-dark box tests. These results are consistent with data that noradrenergic activity is anxiogenic and adrenergic receptor antagonists reverse anxiety behavior (Goddard et al., 2010, Katayama et al., 2010, Kukolja et al., 2008, Morilak et al., 2005, Schank et al., 2008). We did not see changes in overall distance travelled in the open field chamber, demonstrating a lack of effect on motor activity, in agreement with that previously reported for NET+/− mice (Hall et al., 2009). NET−/− mice also show little or no change in motor activity (Hall et al., 2011, Xu et al., 2000). In the TST, NET+/− mice did not demonstrate a difference in immobility time, whereas NET−/− mice demonstrate a decreased immobility in forced swim and tail suspension test (Dziedzicka-Wasylewska et al., 2006, Haenisch et al., 2009b, Perona et al., 2008, Xu et al., 2000). A possible explanation for this difference is that the minimal loss of transport in the NET+/− mice is not sufficient to generate the TST phenotype observed in NET−/− mice.

NET+/− mice were not impaired in spatial learning on the MWM, indicated by performance levels that were not different from NET+/+ mice in both the acquisition phase and probe trials. However, NET+/− mice were impaired in the reversal phase of learning on the MWM. The observation of a selective effect on reversal learning may stem from the reliance of reversal learning performance on the ability of the animal to engage behavioral flexibility, subserved, at least in part, by the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Impaired reversal learning but not acquisition learning have been associated with disruptions to medial PFC activity (De Bruin et al., 1994, Lacroix et al., 2002, Quan et al., 2011). Given the importance of NE and DA to PFC function, changes in this brain region may contribute to the selective effect of reversal learning we observe. The impaired performance could also be attributed to a stress-sensitive component to reversal learning in MWM (Quan et al., 2011).

The observation of behavioral phenotypes in NET+/− mice despite small changes in NET activity might be accounted for in several ways. First, it could reflect an inability of NET+/− mice to respond to situations of stress or cognitive demand that might require a greater transporter reserve to handle enhanced NE neuronal activity and NE release. Such a behavior-related increase in choline transporter availability occurs in mice performing an attention task (Apparsundaram et al., 2005). It has been reported that differences between NET+/+ and NET+/− mice in the forced swim test only emerge following stress, supporting an interaction of NET deficiency with stress-induced behavioral regulation (Haller et al., 2002). Second, brain regions of NE innervation not assessed in the present study might undergo a loss of transport that contributes to the behavioral phenotypes. For example, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) receives a dense noradrenergic projection and ablation of this projection or pharmacological inhibition of NE receptors within the BNST disrupts anxiety and fear responding (McElligott & Winder, 2009). Additionally, a higher level of anatomical resolution of NE terminal regions might reveal altered NET activity. For example, the observed reversal learning impairment suggests that NET in the mPFC division of the frontal cortex could be selectively affected. Finally, NET+/− mice could exhibit developmental compensations in other molecules important to NE signaling or in other neurotransmitter pathways. Reports in NET−/− mice demonstrate that alpha1 and β adrenergic receptors are down-regulated (Bohn et al., 2000, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska et al., 2006, Xu et al., 2000), alpha2 adrenergic receptors are upregulated (Gilsbach et al., 2006, Vizi et al., 2004), presynaptic DA neurotransmission is reduced, dopamine D2/D3 receptor sensitivity is increased (Xu et al., 2000), and neurotrophin-3 and nerve growth factor expression is altered (Haenisch et al., 2008). Thus, it will be valuable for future studies to assess NET activity in other NE terminal regions and neuronal subpopulations, address the influence of task performance and stress on NET activity, and examine other mechanisms of compensation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Marc Caron for the NET knockout line of mice. We acknowledge the Vanderbilt Murine Neurobehavioral facility and Dr. Gregg Stanwood for assistance with behavioral tests. We thank Madeline Tolish and Victoria Ham for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH K01MH076018 (M.K.H.) and NIH MH065215-08 (J.S.R.).

REFERENCES

- Ahern TH, Javors MA, Eagles DA, Martillotti J, Mitchell HA, Liles LC, Weinshenker D. The effects of chronic norepinephrine transporter inactivation on seizure susceptibility in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:730–738. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amphoux A, Vialou V, Drescher E, Bruss M, Mannoury La Cour C, Rochat C, Millan MJ, Giros B, Bonisch H, Gautron S. Differential pharmacological in vitro properties of organic cation transporters and regional distribution in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apparsundaram S, Galli A, DeFelice LJ, Hartzell HC, Blakely RD. Acute regulation of norepinephrine transport: I. protein kinase C- linked muscarinic receptors influence transport capacity and transporter density in SK-N-SH cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998a;287:733–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apparsundaram S, Martinez V, Parikh V, Kozak R, Sarter M. Increased capacity and density of choline transporters situated in synaptic membranes of the right medial prefrontal cortex of attentional task-performing rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3851–3856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0205-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apparsundaram S, Schroeter S, Giovanetti E, Blakely RD. Acute regulation of norepinephrine transport: II. PKC-modulated surface expression of human norepinephrine transporter proteins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998b;287:744–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apparsundaram S, Sung U, Price RD, Blakely RD. Trafficking-Dependent and - Independent Pathways of Neurotransmitter Transporter Regulation Differentially Involving p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Revealed in Studies of Insulin Modulation of Norepinephrine Transport in SK-N-SH Cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:666–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Pliszka SR. Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baganz NL, Horton RE, Calderon AS, Owens WA, Munn JL, Watts LT, Koldzic-Zivanovic N, Jeske NA, Koek W, Toney GM, Daws LC. Organic cation transporter 3: Keeping the brake on extracellular serotonin in serotonintransporter-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18976–18981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800466105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beane M, Marrocco RT. Norepinephrine and acetylcholine mediation of the components of reflexive attention: implications for attention deficit disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:167–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengel D, Murphy DL, Andrews AM, Wichems CH, Feltner D, Heils A, Mossner R, Westphal H, Lesch KP. Altered brain serotonin homeostasis and locomotor insensitivity to 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“Ecstasy”) in serotonin transporter-deficient mice. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:649–655. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom DA, Kellar KJ. Adrenergic and serotonergic receptor binding in rat brain after chronic desmethylimipramine treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1979;209:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Spencer T. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a noradrenergic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1234–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund M, Sirvio J, Riekkinen M, Sallinen J, Scheinin M, Riekkinen P., Jr. Overexpression of alpha2C-adrenoceptors impairs water maze navigation. Neuroscience. 2000;95:481–487. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb AJ, Addington AM, Sidransky E, Gornick MC, Lerch JP, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, Sharp WS, Inoff-Germain G, Wavrant-De Vrieze F, Arcos-Burgos M, Straub RE, Hardy JA, Castellanos FX, Rapoport JL. Support for association between ADHD and two candidate genes: NET1 and DRD1. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134:67–72. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Xu F, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Potentiated opioid analgesia in norepinephrine transporter knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9040–9045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09040.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B, Harney JT, Ahmed BA, Jeffus BC, Unal R, Mehta JL, Kilic F. Plasma serotonin levels and the platelet serotonin transporter. J Neurochem. 2007;102:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes K, Xu X, Chen W, Zhou K, Neale B, Lowe N, Anney R, Franke B, Gill M, Ebstein R, Buitelaar J, Sham P, Campbell D, Knight J, Andreou P, Altink M, Arnold R, Boer F, Buschgens C, Butler L, Christiansen H, Feldman L, Fleischman K, Fliers E, Howe-Forbes R, Goldfarb A, Heise A, Gabriels I, Korn-Lubetzki I, Johansson L, Marco R, Medad S, Minderaa R, Mulas F, Muller U, Mulligan A, Rabin K, Rommelse N, Sethna V, Sorohan J, Uebel H, Psychogiou L, Weeks A, Barrett R, Craig I, Banaschewski T, Sonuga-Barke E, Eisenberg J, Kuntsi J, Manor I, McGuffin P, Miranda A, Oades RD, Plomin R, Roeyers H, Rothenberger A, Sergeant J, Steinhausen HC, Taylor E, Thompson M, Faraone SV, Asherson P. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:934–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttenschon HN, Kristensen AS, Buch HN, Andersen JH, Bonde JP, Grynderup M, Hansen AM, Kolstad H, Kaergaard A, Kaerlev L, Mikkelsen S, Thomsen JF, Koefoed P, Erhardt A, Woldbye DP, Borglum AD, Mors O. The norepinephrine transporter gene is a candidate gene for panic disorder. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:969–976. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira JJ, Pego JM, Taipa R, Bessa JM, Almeida OF, Sousa N. Morphological correlates of corticosteroid-induced changes in prefrontal cortexdependent behaviors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7792–7800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EC, Rajkowski J, Cohen JD, Aston-Jones G. Phasic activation of monkey locus ceruleus neurons by simple decisions in a forced-choice task. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9914–9920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2446-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin JP, Sanchez-Santed F, Heinsbroek RP, Donker A, Postmes P. A behavioural analysis of rats with damage to the medial prefrontal cortex using the Morris water maze: evidence for behavioural flexibility, but not for impaired spatial navigation. Brain Res. 1994;652:323–333. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MW, McGaugh JL. Effects of concurrent manipulations of cholinergic and noradrenergic function on learning and retention in mice. Brain Res. 1989;477:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund M, Sirvio J, Riekkinen M, Sallinen J, Scheinin M, Riekkinen P., Jr. Overexpression of alpha2C-adrenoceptors impairs water maze navigation. Neuroscience. 2000;95:481–487. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb AJ, Addington AM, Sidransky E, Gornick MC, Lerch JP, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, Sharp WS, Inoff-Germain G, Wavrant-De Vrieze F, Arcos-Burgos M, Straub RE, Hardy JA, Castellanos FX, Rapoport JL. Support for association between ADHD and two candidate genes: NET1 and DRD1. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134:67–72. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Xu F, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Potentiated opioid analgesia in norepinephrine transporter knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9040–9045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09040.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B, Harney JT, Ahmed BA, Jeffus BC, Unal R, Mehta JL, Kilic F. Plasma serotonin levels and the platelet serotonin transporter. J Neurochem. 2007;102:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes K, Xu X, Chen W, Zhou K, Neale B, Lowe N, Anney R, Franke B, Gill M, Ebstein R, Buitelaar J, Sham P, Campbell D, Knight J, Andreou P, Altink M, Arnold R, Boer F, Buschgens C, Butler L, Christiansen H, Feldman L, Fleischman K, Fliers E, Howe-Forbes R, Goldfarb A, Heise A, Gabriels I, Korn-Lubetzki I, Johansson L, Marco R, Medad S, Minderaa R, Mulas F, Muller U, Mulligan A, Rabin K, Rommelse N, Sethna V, Sorohan J, Uebel H, Psychogiou L, Weeks A, Barrett R, Craig I, Banaschewski T, Sonuga-Barke E, Eisenberg J, Kuntsi J, Manor I, McGuffin P, Miranda A, Oades RD, Plomin R, Roeyers H, Rothenberger A, Sergeant J, Steinhausen HC, Taylor E, Thompson M, Faraone SV, Asherson P. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:934–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttenschon HN, Kristensen AS, Buch HN, Andersen JH, Bonde JP, Grynderup M, Hansen AM, Kolstad H, Kaergaard A, Kaerlev L, Mikkelsen S, Thomsen JF, Koefoed P, Erhardt A, Woldbye DP, Borglum AD, Mors O. The norepinephrine transporter gene is a candidate gene for panic disorder. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:969–976. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira JJ, Pego JM, Taipa R, Bessa JM, Almeida OF, Sousa N. Morphological correlates of corticosteroid-induced changes in prefrontal cortexdependent behaviors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7792–7800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EC, Rajkowski J, Cohen JD, Aston-Jones G. Phasic activation of monkey locus ceruleus neurons by simple decisions in a forced-choice task. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9914–9920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2446-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin JP, Sanchez-Santed F, Heinsbroek RP, Donker A, Postmes P. A behavioural analysis of rats with damage to the medial prefrontal cortex using the Morris water maze: evidence for behavioural flexibility, but not for impaired spatial navigation. Brain Res. 1994;652:323–333. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MW, McGaugh JL. Effects of concurrent manipulations of cholinergic and noradrenergic function on learning and retention in mice. Brain Res. 1989;477:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M, Faron-Gorecka A, Kusmider M, Drozdowska E, Rogoz Z, Siwanowicz J, Caron MG, Bonisch H. Effect of antidepressant drugs in mice lacking the norepinephrine transporter. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2424–2432. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter J, Page GP, Stein MB, Woods SW. Genome-wide linkage scan for loci predisposing to social phobia: evidence for a chromosome 16 risk locus. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:59–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsbach R, Faron-Gorecka A, Rogoz Z, Bruss M, Caron MG, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M, Bonisch H. Norepinephrine transporter knockout-induced up-regulation of brain alpha2A/C-adrenergic receptors. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard AW, Ball SG, Martinez J, Robinson MJ, Yang CR, Russell JM, Shekhar A. Current perspectives of the roles of the central norepinephrine system in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:339–350. doi: 10.1002/da.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MM, Weiss JM. Effects of chronic antidepressant drug administration and electroconvulsive shock on locus coeruleus electrophysiologic activity. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:117–129. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00936-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenisch B, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Caron MG, Bonisch H. Knockout of the norepinephrine transporter and pharmacologically diverse antidepressants prevent behavioral and brain neurotrophin alterations in two chronic stress models of depression. J Neurochem. 2009a;111:403–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenisch B, Gilsbach R, Bonisch H. Neurotrophin and neuropeptide expression in mouse brain is regulated by knockout of the norepinephrine transporter. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:973–982. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenisch B, Linsel K, Bruss M, Gilsbach R, Propping P, Nothen MM, Rietschel M, Fimmers R, Maier W, Zobel A, Hofels S, Guttenthaler V, Gothert M, Bonisch H. Association of major depression with rare functional variants in norepinephrine transporter and serotonin1A receptor genes. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009b;150B:1013–1016. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MK, Blackford JU, Haman K, Mazei-Robison M, English BA, Prasad HC, Steele A, Hazelwood L, Fentress HM, Myers R, Blakely RD, Sanders-Bush E, Shelton R. Multivariate permutation analysis associates multiple polymorphisms with subphenotypes of major depression. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MK, Blakely RD. Gene organization and polymorphisms of monoamine transporters. Relationship to psychiatric and other complex diseases. In: Reith MEA, editor. Neurotransmitter transporters. Structure, function, and regulation. Humana Press; Totowa: 2002. pp. 111–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MK, Blakely RD. The Functional Impact of Monoamine Transporter Genetic Variation. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:16.11–16.41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MK, Mazei-Robison MS, Blakely RD. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human norepinephrine transporter gene affect expression, trafficking, antidepressant interaction, and protein kinase C regulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:457–466. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MK, Robertson D, Blakely RD. A mutation in the human norepinephrine transporter gene (SLC6A2) associated with orthostatic intolerance disrupts surface expression of mutant and wild-type transporters. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4470–4478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04470.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MK, Steele A, Couch RS, Stein MA, Krueger JJ. Novel and functional norepinephrine transporter protein variants identified in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Li XF, Randall-Thompson J, Sora I, Murphy DL, Lesch KP, Caron M, Uhl GR. Cocaine-conditioned locomotion in dopamine transporter, norepinephrine transporter and 5-HT transporter knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Schwarzbaum JM, Perona MT, Templin JS, Caron MG, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, Uhl GR. A greater role for the norepinephrine transporter than the serotonin transporter in murine nociception. Neuroscience. 2011;175:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Bakos N, Rodriguiz RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Liposits Z. Behavioral responses to social stress in noradrenaline transporter knockout mice: effects on social behavior and depression. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00789-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halushka MK, Fan JB, Bentley K, Hsie L, Shen N, Weder A, Cooper R, Lipshutz R, Chakravarti A. Patterns of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in candidate genes for blood-pressure homeostasis. Nat Genet. 1999;22:239–247. doi: 10.1038/10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield T, McGaugh JL. Norepinephrine infused into the basolateral amygdala posttraining enhances retention in a spatial water maze task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1999;71:232–239. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Itoh K, Yoshida K, Shimizu T, Suzuki T. Positive association between T-182C polymorphism in the norepinephrine transporter gene and susceptibility to major depressive disorder in a japanese population. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50:301–304. doi: 10.1159/000080957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Invernizzi RW, Garattini S. Role of presynaptic alpha2-adrenoceptors in antidepressant action: recent findings from microdialysis studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen LL. The uptake of noradrenaline by the isolated rat heart. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1963;21:523–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1963.tb02020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen LL. Role of transmitter uptake mechanisms in synaptic neurotransmission. Br J Pharmacol. 1971;41:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1971.tb07066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi LD, Samuvel DJ, Blakely RD, Ramamoorthy S. Evidence for biphasic effects of protein kinase C on serotonin transporter function, endocytosis, and phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:2077–2087. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi LD, Samuvel DJ, Ramamoorthy S. Regulated internalization and phosphorylation of the native norepinephrine transporter in response to phorbol esters. Evidence for localization in lipid rafts and lipid raft-mediated internalization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19315–19326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SR, Gainetdinov RR, Jaber M, Giros B, Wightman RM, Caron MG. Profound neuronal plasticity in response to inactivation of the dopamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4029–4034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski RM, Shippenberg TS, Witkin JM, Rocha BA. Genetic deletion of the norepinephrine transporter decreases vulnerability to seizures. Neurosci Lett. 2005;382:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama K, Yamada K, Ornthanalai VG, Inoue T, Ota M, Murphy NP, Aruga J. Slitrk1-deficient mice display elevated anxiety-like behavior and noradrenergic abnormalities. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:177–184. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller NR, Diedrich A, Appalsamy M, Miller LC, Caron MG, McDonald MP, Shelton RC, Blakely RD, Robertson D. Norepinephrine transporter-deficient mice respond to anxiety producing and fearful environments with bradycardia and hypotension. Neuroscience. 2006;139:931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller NR, Diedrich A, Appalsamy M, Tuntrakool S, Lonce S, Finney C, Caron MG, Robertson D. Norepinephrine transporter-deficient mice exhibit excessive tachycardia and elevated blood pressure with wakefulness and activity. Circulation. 2004;110:1191–1196. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141804.90845.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Hahn MK, Joung Y, Anderson SL, Steele AH, Mazei-Robinson MS, Gizer I, Teicher MH, Cohen BM, Robertson D, Waldman ID, Blakely RD, Kim KS. A polymorphism in the norepinephrine transporter gene alters promoter activity and is associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;50:19164–19169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510836103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Biederman J, McGrath CL, Doyle AE, Mick E, Fagerness J, Purcell S, Smoller JW, Sklar P, Faraone SV. Further evidence of association between two NET single-nucleotide polymorphisms with ADHD. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:624–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H, Lips K, Volk C. Polyspecific organic cation transporters: structure, function, physiological roles, and biopharmaceutical implications. Pharmaceutical research. 2007;24:1227–1251. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli U, Hahn MK, English BA, Sofowora GG, Muszkat M, Li C, Blakely RD, Stein CM, Kurnik D. Genetic variation in the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter is associated with blood pressure responses to exercise in healthy humans. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2011;21:171–178. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328344f63e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukolja J, Schlapfer TE, Keysers C, Klingmuller D, Maier W, Fink GR, Hurlemann R. Modeling a negative response bias in the human amygdala by noradrenergicglucocorticoid interactions. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12868–12876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3592-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix L, White I, Feldon J. Effect of excitotoxic lesions of rat medial prefrontal cortex on spatial memory. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BE. The role of noradrenaline in depression: a review. J Psychopharmacol. 1997;11:S39–S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElligott ZA, Winder DG. Modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:1329–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanez S, Owens WA, Gould GG, Murphy DL, Daws LC. Exaggerated effect of fluvoxamine in heterozygote serotonin transporter knockout mice. J Neurochem. 2003;86:210–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Barrera G, Echevarria DJ, Garcia AS, Hernandez A, Ma S, Petre CO. Role of brain norepinephrine in the behavioral response to stress. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1214–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Frazer A. Antidepressants and brain monoaminergic systems: a dimensional approach to understanding their behavioural effects in depression and anxiety disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;7:193–218. doi: 10.1017/S1461145704004080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moron JA, Brockington A, Wise RA, Rocha BA, Hope BT. Dopamine uptake through the norepinephrine transporter in brain regions with low levels of the dopamine transporter: evidence from knock-out mouse lines. J Neurosci. 2002;22:389–395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00389.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N. The family of Na+/Cl− neurotransmitter transporters. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1785–1803. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, McMahon A, Sabban EL, Tallman JF, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant administration decreases the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase in the rat locus coeruleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7522–7526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parini S, Renoldi G, Battaglia A, Invernizzi RW. Chronic reboxetine desensitizes terminal but not somatodendritic alpha2-adrenoceptors controlling noradrenaline release in the rat dorsal hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez XA, Andrews AM. Chronoamperometry to determine differential reductions in uptake in brain synaptosomes from serotonin transporter knockout mice. Anal Chem. 2005;77:818–826. doi: 10.1021/ac049103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona MT, Waters S, Hall FS, Sora I, Lesch KP, Murphy DL, Caron M, Uhl GR. Animal models of depression in dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine transporter knockout mice: prominent effects of dopamine transporter deletions. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:566–574. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830cd80f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR. The neuropsychopharmacology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan M, Zheng C, Zhang N, Han D, Tian Y, Zhang T, Yang Z. Impairments of behavior, information flow between thalamus and cortex, and prefrontal cortical synaptic plasticity in an animal model of depression. Brain Res Bull. 2011;85:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy S, Blakely RD. Phosphorylation and sequestration of serotonin transporters differentially modulated by psychostimulants. Science. 1999;285:763–766. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1219–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SD, Matthies HJ, Owens WA, Sathananthan V, Christianson NS, Kennedy JP, Lindsley CW, Daws LC, Galli A. Insulin reveals Akt signaling as a novel regulator of norepinephrine transporter trafficking and norepinephrine homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11305–11316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0126-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Hahn EL, Nathan SV, de Quervain DJ, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid effects on memory retrieval require concurrent noradrenergic activity in the hippocampus and basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8161–8169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2574-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu SH, Lee SH, Lee HJ, Cha JH, Ham BJ, Han CS, Choi MJ, Lee MS. Association between norepinephrine transporter gene polymorphism and major depression. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;49:174–177. doi: 10.1159/000077361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank JR, Liles LC, Weinshenker D. Norepinephrine signaling through betaadrenergic receptors is critical for expression of cocaine-induced anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomig E, Babin-Ebell J, Russ H. 1,1′-diethyl-2,2′-cyanine (decynium22) potently inhibits the renal transport of organic cations. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;347:379–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00165387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta SM, Grizenko N, Thakur GA, Bellingham J, DeGuzman R, Robinson S, TerStepanian M, Poloskia A, Shaheen SM, Fortier ME, Choudhry Z, Joober R. Differential association between the norepinephrine transporter gene and ADHD: role of sex and subtype. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:129–137. doi: 10.1503/jpn.110073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon JR, Flattem NL, Jordan J, Jacob G, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Blakely RD, Robertson D. Clues to the origin of orthostatic intolerance: a genetic defect in the cocaine- and antidepressant sensitive norepinephrine transporter. New Eng J Med. 2000;342:541–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirey-Rice JK, Klar R, Fentress HM, Redmon SN, Sabb TR, Krueger JJ, Wallace NM, Appalsamy M, Finney C, Lonce S, Diedrich A, Hahn MK. Norepinephrine transporter A457P knock-in mice display key features of human postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2013 doi: 10.1242/dmm.012203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solich J, Faron-Gorecka A, Kusmider M, Palach P, Gaska M, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. Norepinephrine transporter (NET) knock-out upregulates dopamine and serotonin transporters in the mouse brain. Neurochem Int. 2011;59:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa N, Lukoyanov NV, Madeira MD, Almeida OF, Paula-Barbosa MM. Reorganization of the morphology of hippocampal neurites and synapses after stress-induced damage correlates with behavioral improvement. Neuroscience. 2000;97:253–266. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, Prince J, Hatch M, Jones J, Harding M, Faraone SV, Seidman L. Effectiveness and tolerability of tomoxetine in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:693–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung U, Apparsundaram S, Galli A, Kahlig K, Savchenko V, Schroeter S, Quick MW, Blakely RD. A regulated interaction of syntaxin 1A with the antidepressantsensitive norepinephrine transporter establishes catecholamine clearance capacity. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:1697–1709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01697.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uher R, Huezo-Diaz P, Perroud N, Smith R, Rietschel M, Mors O, Hauser J, Maier W, Kozel D, Henigsberg N, Barreto M, Placentino A, Dernovsek MZ, Schulze TG, Kalember P, Zobel A, Czerski PM, Larsen ER, Souery D, Giovannini C, Gray JM, Lewis CM, Farmer A, Aitchison KJ, McGuffin P, Craig I. Genetic predictors of response to antidepressants in the GENDEP project. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009 doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizi ES, Zsilla G, Caron MG, Kiss JP. Uptake and release of norepinephrine by serotonergic terminals in norepinephrine transporter knock-out mice: implications for the action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7888–7894. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1506-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D, White SS, Javors MA, Palmiter RD, Szot P. Regulation of norepinephrine transporter abundance by catecholamines and desipramine in vivo. Brain Res. 2002;946:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth TL, Herndon LC, Quick MW. Psychostimulants differentially regulate serotonin transporter expression in thalamocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-j0003.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth TL, Quick MW. Substrate-induced regulation of gammaaminobutyric acid transporter trafficking requires tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42932–42937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Gainetdinov RR, Wetsel WC, Jones SR, Bohn LM, Miller GW, Wang YM, Caron MG. Mice lacking the norepinephrine transporter are supersensitive to psychostimulants. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:465–471. doi: 10.1038/74839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Hawi Z, Brookes KJ, Anney R, Bellgrove M, Franke B, Barry E, Chen W, Kuntsi J, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Ebstein R, Fitzgerald M, Miranda A, Oades RD, Roeyers H, Rothenberger A, Sergeant J, Sonuga-Barke E, Steinhausen HC, Faraone SV, Gill M, Asherson P. Replication of a rare protective allele in the noradrenaline transporter gene and ADHD. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1564–1567. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Knight J, Brookes K, Mill J, Sham P, Craig I, Taylor E, Asherson P. DNA pooling analysis of 21 norepinephrine transporter gene SNPs with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: no evidence for association. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134:115–118. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Takahashi H, Higuchi H, Kamata M, Ito K, Sato K, Naito S, Shimizu T, Itoh K, Inoue K, Suzuki T, Nemeroff CB. Prediction of antidepressant response to milnacipran by norepinephrine transporter gene polymorphisms. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1575–1580. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CB, Carneiro AM, Dostmann WR, Hewlett WA, Blakely RD. p38 MAPK activation elevates serotonin transport activity via a trafficking-independent, protein phosphatase 2A-dependent process. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15649–15658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CB, Hewlett WA, Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I, Blakely RD. Adenosine receptor, protein kinase G, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent upregulation of serotonin transporters involves both transporter trafficking and activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1462–1474. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]