Abstract

Incarceration has been extensively linked with HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). While a great deal of attention has been given to the risk behaviors of people who have been incarcerated, examination of the behaviors of partners of incarcerated individuals is also needed to understand the direct and indirect links between incarceration and HIV and to identify prevention avenues. In the present study, we hypothesize that incarceration is associated with risk behavior through attitudes and norms. The purpose of this paper is: (1) to describe the attitudes and norms about sexual behaviors that women have when a sexual partner is incarcerated; and (2) to examine the association between attitudes and norms with the behavior of having other sex partners while a main partner is incarcerated. In our sample (n = 175), 50 % of women reported having other sex partners while their partner was incarcerated. Our findings show that attitudes, descriptive norms (i.e., norms about what other people do), and injunctive norms (i.e., norms about what others think is appropriate) were associated with having other partners. Interventions designed for couples at pre- and post-release from prison are needed to develop risk reduction plans and encourage HIV/STI testing prior to their reunion.

Keywords: HIV, Incarceration, Women, Norms

Introduction

Over the last 35 years, the prison population has grown dramatically in the U.S.A. as a result of radical changes in policies of crime control and sentencing, particularly those related to the war on drugs.1 Researchers have demonstrated a strong connection between incarceration and physical and mental health problems as well as homelessness, substance use, and poverty. 2–6

Incarceration has been linked with HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).7–11 The number of AIDS cases in prisons is twice the number of the total U.S. general population.12 In 2008, 1.5 % of the federal and state male inmate population and 1.9 % of the female population were HIV seropositive; in Maryland, 2.5 % of the male and 4.2 % of the female inmate population were HIV seropositive.12

Men with a history of incarceration are three to six times more likely to be infected with HIV than men with no history of incarceration.13,14 High prevalence of drug use and sexual risk behaviors within this group facilitate HIV transmission.15 Further, prior research has also shown that high-risk drug and sexual behaviors do occur in prison settings, which also contributes to HIV risk and transmisson.16 Sexual risk behaviors that have been associated with personal history of incarceration among both men and women include sexual concurrency, having multiple partners, unprotected vaginal sex or inconsistent condom use, and exchange or transactional sex.17–24

An estimated 50–80 % of inmates are married or in a committed relationship when they are incarcerated.25–27 A growing body of research has focused on describing relationships and sexual risk among inmates and their partners.25,26,28 Having a partner who has been incarcerated has been associated with numerous high-risk behaviors, including partner concurrency,17,18,22,29 multiple sex partners,19,30,31 unprotected sex,28 transactional sex,30–32 and forced sex.32 Much of this research has focused on the role of the incarcerated partner. Examination of the behaviors of partners “on the outside” (i.e., not incarcerated) is needed to understand the direct and indirect links between incarceration and HIV and to identify prevention avenues.33

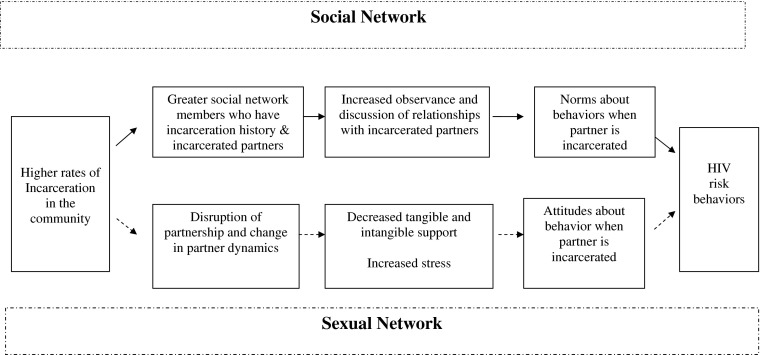

In Figure 1, we present two hypothesized pathways by which incarceration impacts HIV risk behaviors through social networks. Incarceration may change social networks and sexual networks. Clear and colleagues note that a multitude of social networks are disrupted as different people are incarcerated year after year.34 Social networks include a variety of individuals such as family, friends, co-workers, and neighbors. Sexual networks refer to a subgroup of the social network, the sex partners.

Figure 1.

Proposed pathways of the relationship between incarceration, social networks, and risky sexual behaviors.

The first pathway (solid black line) illustrates how changes in the social network lead to HIV risk behavior. With high rates of incarceration among disadvantaged populations such as out sample, there is a greater likelihood that a person will have someone in their network who is or has been incarcerated. Also, this person may interact with a greater number of people who have incarcerated partners. Through these interactions, there are opportunities to observe and discuss relationships that people have with incarcerated people and how people act when their partner in incarcerated. These opportunities may lead to the establishment and proliferation of norms about what behaviors are appropriate and commonly practiced when a partner is incarcerated. Thus, incarceration indirectly influences relationships and sexual behaviors by influencing community norms.35–37

Norms refer to one’s perceptions of what behaviors are practiced by others (i.e., descriptive norms) as well as what behaviors are accepted or approved (injunctive norms).38 Thus, if a person believes that other people “step out of the relationship” or approve of having other sexual partners when a partner is incarcerated, this person may be likely to practice similar behaviors. Norms have consistently been found to be associated with several risky sexual behaviors including unprotected sex and exchanging sex for money or drugs.39,40 However, little is known about norms regarding sexual behaviors when a partner is incarcerated within a population with high rates of incarceration.

The second pathway in Figure 1 shows that a second consequence of incarceration is changes in sexual networks (dashed line). Incarceration disrupts relationships and changes partner dynamics, which may lead to seeking out other partners.41 Incarceration affects sexual relationships directly through the removal of a partner and the emotional and material support they provided,42 which may lead non-incarcerated partner to experience emotional distress and financial challenges.43 In addition, when children are involved, the non-incarcerated partner may have increased child care-giving burden.44 This experience may shape one’s attitudes about incarceration and having relationships with incarcerated individuals. To overcome these financial and emotional burdens, women may seek additional partners while their partner is incarcerated. To rationalize this behavior, women may begin to feel that is it ok to have other sex partners because of these situations.

The current study focuses on a sample of predominantly African American women who were in a relationship with a sexual partner who was incarcerated for 6 months or longer during their relationship. The purpose of this paper is: (1) to describe the attitudes and norms about sexual behaviors when a sexual partner is incarcerated; and (2) to examine the association between attitudes and norms with the behavior of having other sex partners while a main partner is incarcerated.

Methods

Study Population and Procedures

The current study is a cross-sectional analysis embedded in the CHAT project, a longitudinal evaluation of a social network based HIV/STI prevention intervention. The CHAT intervention was designed to train women to be peer mentors who promoted HIV and STI risk reduction in their social networks. The goal of the intervention was to teach women (called “index participants”) about HIV risk reduction. These women would then share the information and resources with people in their social networks. The sample was comprised of two types of participants—index (76 %) and network participants (24 %). Index participants were recruited through street outreach, referrals, and word-of-mouth. After completing a baseline visit, index participants referred their social network members to the study (i.e., network participants). While index participants participated in the intervention phase of the study, network participants only participated in assessment visits. (For more information on recruitment and the intervention see Davey-Rothwell et al.45).

Eligibility criteria for index participants included (1) female; (2) 18–55 years; (3) did not inject drugs in the past 6 months; (4) self-reported sex with at least one male partner in the past 6 months; and (5) at least one of the following risk behaviors in the past 6 months: (a) more than two sex partners; (b) recent STI diagnosis, and (c) having a high-risk sex partner (i.e., injected heroin or cocaine, smoked crack, HIV seropositive, or man who has sex with men). Index participants also referred social network members to the study. Eligibility for network participants included: (1) injecting heroin or cocaine in the past 6 months, (2) sex partners of the index participant, or (3) people the index participants felt comfortable talking to about HIV or STIs.

Both index and network participants completed the same study visits which were conducted at a community-based research center. After providing written consent, participants took part in an interview. Part of the interview was administered by a trained interviewer and part was administered through audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). At the end of each survey visit, participants received an individualized consultation about the need for referrals from our extensive database of resources on local medical and social service agencies, as well as risk reduction materials. Participants were also welcomed to come back to the clinic to get additional referrals and resources.

Participants were compensated with $35 for completion of the interview. Measurements regarding attitudes, norms, and behaviors while a partner was incarcerated were collected during the 6-month follow-up visits, which were conducted during May 2006 and June 2008. This study was conducted in Baltimore, MD, USA. All study procedures were reviewed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Incarcerated Partners Measures

Prior to the start of the data collection, we conducted a brief piloting phase with 32 women. Through brief semi-structured interviews, we asked about the frequency of having incarcerated partners, views of how incarceration impacts relationships, their behaviors when a partner was incarcerated, and the daily context of having a partner who was incarcerated. The results of this piloting were used to develop items to measure attitudes and norms. We used 6 months as the time frame to indicate that the questions pertained to relationships when a main partner, rather than a casual partner, is incarcerated.

Behaviors and Background

All study participants were asked if they ever had a sexual partner who was incarcerated for at least 6 months during the relationship. Participants who reported yes were subsequently asked, “How long were you with this partner before he or she was incarcerated?”

Next, participants were asked, “While that partner was incarcerated, did you have any other sexual partners?” Participants reporting other sexual partners were also asked whether the incarcerated partner knew of the other sexual partners.

To assess the continuity of the relationship after the partner was released, participants were asked, “When your incarcerated partner was released, did you start having sex with this partner again?” Participants who reported re-initiating sexual activity with the incarcerated partner were also asked, “When your incarcerated partner was released, did you use a condom with him or her the first time you had sex again?” and, “When the partner was released, did he or she get tested for HIV before you started having sex with this partner again?”

Attitudes and Norms

The study measured eight statements indicating attitudes and norms about having additional partners while a sexual partner was incarcerated and risk of having sex with someone recently incarcerated. All statements were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly agree”, 2 = “agree”, 3 = “neither agree nor disagree, 4 = “disagree”, and 5 = “strongly disagree”). Some items were recoded to ensure that all items were in the same direction.

We performed principal component analysis (PCA) of the eight items to determine if any of the items were correlated together, thus signifying a subconstruct (i.e., factor) within the scale. The criteria used to determine the number of meaningful factors to retain were the Keiser–Guttman rule of an eigenvalue greater than 1.0, component with greater than 10 % of the proportion of variance extracted, the scree test and parallel analysis. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to determine which items clustered together using maximum likelihood extraction, followed by an oblique rotation (promax) of the loading matrix. Factor loadings > ±0.40 were considered meaningful loadings with a factor if also the factor loading with the other factors was low (<±0.20).46 Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess internal consistency of the items for each factor derived from EFA.

Based on the factor analysis, four items loaded on one factor and the other four items were individual items. The four items in the factor measuring attitudes were:

- If a person’s main partner is incarcerated for 6 months or longer, (attitudes factor)

- it is okay for that person to have other sex partners.

- it is okay for that person to have other sex partners if they get lonely.

- it is okay for that person to have sex with other people who can provide for them.

- that person should remain faithful and not have other sex partners.

The four individual items were:

It is riskier to have sex with a person who was recently incarcerated. (Attitude)

If my partner was in prison for 6 months or longer, most of my friends would think it was okay if I had sex with someone else. (Injunctive norms)

Most of my friends would go out with someone else, if their partner was in prison for 6 months or longer. (Descriptive norms A)

Most of my friends would hide going out with someone else, if their partner was in prison for 6 months or longer. (Descriptive norms B)

Sexual Risk Behaviors

Participants were also asked about their sexual behaviors in the past 90 days. Specifically, participants reported the number of sex partners they had in the past 90 days and the frequency of condom use during vaginal and anal sex (coded as always vs. less than always). Participants were asked if they knew or suspected any of their sex partners had any of the following characteristic: injected drugs, smoked crack, HIV+, had a STI, or a male sex partner who had sex with other men. Finally, participants were asked if they had sex while they were high or drunk in the past 90 days.

Substance Use

Participants self-reported their use of heroin and cocaine. A dichotomous variable was created to measure use of these drugs (regardless of route of administration) in the past 6 months. In addition, since smoking crack has been linked to risky sex behaviors,47,48 we also created a variable of smoked crack in the past 6 months.

Participants were also asked about their alcohol use. Problem drinking was derived from two questions that asked about drinking frequency and number of drinks on a typical day. We defined high-risk drinking as either (1) drinking at least two or three times a week five or more drinks at a time, or (2) drinking four or more times a week three to four drinks at a time. Women consuming fewer drinks were categorized as not a high-risk drinker. These levels exceed the recommended guideline of alcohol consumption in moderation for women as defined by the USDA.49

Psychosocial Characteristics

Eight items measured participant self-efficacy for using a condom for vaginal sex with their last sex partner under various scenarios (i.e., want to feel close, partner does not want to, or under the influence). Responses included “sure I cannot”, “not sure I can”, and “sure I can”) (alpha = 0.95). Finally, depressive symptoms were assessed through the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) assessment tool.50 A cutpoint of 20 was used to indicate depression. This cutpoint has been used in other studies where depression levels of the sample were high.51

Demographics

Several demographic covariates were also examined including age, race (Black/African American vs. not Black/African American), educational attainment (less than high school vs. high school, GED and any college), and marital status (married/cohabiting vs. not married/not cohabiting. Housing situation was measured with five categories (own/rent house or apartment, rent a room, stay for free in someone else’s place, homeless/two or more different places per week, or other), while unemployment and homeless in the past 6 months was coded as yes or no. Income was coded as less than $500 in the past 30 days versus $500 or more. Participants also reported if they had ever been arrested or spent any time in jail or prison in the past 6 months. Finally, participants were asked about the number of people in their social network who had ever been incarcerated. Several items were dichotomized due to a skewed distribution.

Analyses

The current study was limited to women who reported having ever had a sexual partner who was incarcerated for at least 6 months during the relationship. The baseline dataset included 746 individuals who completed a baseline visit, of which 76 % were female. The 6-month retention rate among women was 78 % (n = 447). Among the women who completed the 6-month survey, 39 % (n = 175) reported having a partner incarcerated for 6 months or longer during their relationship and were retained in the current analysis.

Student t tests were used to examine associations between the outcomes and continuous predictors and χ2 for categorical predictors. Univariate analysis assessed the normality distribution (mean, variance, skewness, and kurtosis) of individual norm and attitude items.

To describe and assess the association between individual attitudes and norms items and the outcome, we used cross-tabulation and χ2 tests. Attitude and norms items were examined nominally with the combined response categories “strongly agree” with “agree” and “strongly disagree” with “disagree”. After the factor analysis, four of the eight items were summed into one factor.

Participants may have been in the relationship with the incarcerated partner prior to enrollment in this study. However, due to the possibility that going through the intervention may influence risk behavior, we examined differences in the outcome between participants who participated in the intervention and those who did not. There were no differences in having an incarcerated partner as well as having other partners when a partner was incarcerated.

In logistic regression models, we examined the attitudes factor, single attitude item, and the remaining descriptive and injunctive norm items simultaneously with the study outcome- having other sex partners while main partner was incarcerated. To facilitate interpretation, attitude and norms variables were converted to z-scores (i.e., standardized).

Multivariate logistic regression models adjusted for variables conceptualized to be most influential in the relationship between attitudes, norms and the incarcerated-related sex behavior. The multivariate model used clustered robust estimation to calculate standard errors to account for correlation between network members of the same network. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC 10.1 for Windows.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants were between 20 to 59 years old with a median age of 42 years, predominantly African Americans (98 %), half (48 %) were currently married or in a committed relationship, 35 % cared for children under 18 years of age, 84 % were unemployed, and 41 % had completed less than a high school education.

Within the past 90 days, about a third (31 %) of the women had between two and four sexual partners and 5 % had five or more sexual partners. High-risk sexual partners were prevalent (40 %), and the most common risk was having a partner who smoked crack or snorted heroin. Half (48 %) of the women had smoked crack or cocaine in the past 6 months.

Approximately 85 % of women reported having ever been arrested. Sixty-three percent of participants had at least one individual (non-partner) in their social network who had been incarcerated.

Relationships with Incarcerated Partners

Approximately 50 % (n = 88) of the women reported having other sex partners while their partner was incarcerated. We examined characteristics of the relationship with the incarcerated partner . The majority (81.1 %) had been in the relationship with the incarcerated partner for at least 1 year. Women currently under the age of 40 were less likely to have been in the relationship with the partner for at least 5 years at the time of incarceration compared to older women (16 % versus 42 % of women aged 40 to 49 years old and 28 % of women aged 50 to 59 years old; p < 0.05). Duration of the relationship at the time of incarceration was not associated with having other sexual partners while the partner was incarcerated (<1 year, 50 %; 1–5 years, 55 %; and >5 years, 45 %, p = 0.55). Two thirds (62.5 %) of the participants who had other sexual partners indicated that the incarcerated partner knew of other sexual partners, and neither duration of the relationship or age of the participant was associated with the incarcerated partner knowing of other sexual partners.

Younger age was the only demographic characteristic associated with having other sexual partners while their partner was incarcerated (p < 0.05; Table 1). Women who had other sexual partners while their partner was incarcerated had higher prevalence of recent sexual risk behaviors compared to women who did not have other sexual partners while partner was incarcerated, including multiple partners (59 versus 15 %, p < 0.001), exchange sex (32 versus 7 %, p < 0.001), and unprotected sex with a non-main partner (48 versus 26 %, p < 0.01). Women with other partners were also more likely to report recent sexual intercourse while high (56 % versus 32 %, p < 0.001) or drunk (40 % versus 26 %, p = 0.06). No differences in prevalence of alcohol and drug use were observed between women who had and did not have other sexual partners while a partner was incarcerated. Women who had other sex partners while a partner was incarcerated were more likely to experience depressive symptoms and have a history of abuse.

Table 1.

Demographic, behavioral and psychosocial characteristics by risk behaviors among women with a history of an incarcerated partner (n = 175)

| Characteristics | Other sexual partners while partner incarcerated (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 88) | No (n = 87) | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (mean, SD)* | 39.9 (8.0) | 43.2 (7.8) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 44.8 | 51.7 |

| Never married | 43.7 | 37.9 |

| Residing with 1+ child in home | 34.1 | 35.6 |

| Less than high school degree | 42.0 | 40.5 |

| Income from all sources past 30 days < $500 | 64.0 | 55.2 |

| Unemployed past 6 months | 86.4 | 81.6 |

| Homeless in the past 6 months | 30.7 | 27.6 |

| Ever been arrested | 82.3 | 87.4 |

| Spent time in jail past 6 months | 24.1 | 16.1 |

| Had at least one social network member who had been incarcerated (excludes sex partner) | 63.2 | 64.4 |

| Sexual behaviors | ||

| 2+ sexual partners past 90 days* | 58.8 | 14.9 |

| Knows/suspect partner past 90 days is MSM, IDU, crack user, HIV + or STI+ | 45.9 | 34.5 |

| Exchange sex past 90 days* | 31.8 | 7.0 |

| Unprotected vaginal sex past 30 days or unprotected anal sex past 90 days with non-main partner* | 48.2 | 26.4 |

| Unprotected vaginal sex past 30 days or unprotected anal sex past 90 days with main partner | 61.2 | 55.2 |

| Had sex while high past 90 days* | 56.5 | 32.2 |

| Had sex while drunk past 90 days*** | 40.0 | 26.4 |

| Substance use past 6 months | ||

| Crack use | 45.5 | 50.6 |

| Any type of cocaine or heroin | 50.0 | 57.5 |

| Problem drinking: ≥10 drinks/week | 19.3 | 17.2 |

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||

| Depressive symptoms: CESD score 20 or higher** | 54.0 | 39.1 |

| Condom self-efficacy mean score (SD)** | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.61) |

A five-point Likert scale was collapsed into three categories: agrees includes “strongly agree” responses, and disagrees includes “strongly disagree”

*p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.10

Attitudes and Norms

The distribution of each individual attitude and norms items are shown in Table 2. The Attitudes towards having other sexual partners while a partner is incarcerated factor was strongly associated with a history of having had other sexual partners while a partner was incarcerated in both univariate and multivariate analysis that adjusts for age and sexual risk behaviors (Table 3). The injunctive norm and descriptive norm A items were marginally associated with history of the incarcerated-related sex behavior.

Table 2.

Distribution of attitudes and norms among women who reported having an incarcerated sex partner and by sexual risk

| Attitudes and norms statementa | Other sexual partners while partner incarcerated (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 88) | No (n = 87) | |

| If a person’s main partner is incarcerated for 6 months or longer | ||

| It is okay for that person to have other sex partners.* | ||

| Agrees | 29.6 | 4.6 |

| Disagrees | 42.0 | 77.0 |

| Neutral | 28.4 | 18.4 |

| It is okay for that person to have other sex partners if they get lonely.* | ||

| Agrees | 37.5 | 16.1 |

| Disagrees | 36.4 | 74.7 |

| Neutral | 26.1 | 9.2 |

| It is okay for that person to have sex with other people who can provide for them.* | ||

| Agrees | 40.9 | 18.4 |

| Disagrees | 34.1 | 71.3 |

| Neutral | 25.0 | 10.3 |

| That person should remain faithful and not have other sex partners.* | ||

| Agrees | 52.3 | 77.0 |

| Disagrees | 26.1 | 10.3 |

| Neutral | 21.6 | 12.6 |

| If my partner was in prison for 6 months or longer, most of my friends would think it was okay if I had sex with someone else.** | ||

| Agrees | 62.5 | 50.0 |

| Disagrees | 25.0 | 43.0 |

| Neutral | 12.5 | 7.0 |

| Most of my friends would go out with someone else, if their partner was in prison for 6 months or longer.* | ||

| Agrees | 81.8 | 71.3 |

| Disagrees | 6.8 | 24.1 |

| Neutral | 11.4 | 4.6 |

| Most of my friends would hide going out with someone else, if their partner was in prison for 6 months or longer.** | ||

| Agrees | 53.4 | 66.7 |

| Disagrees | 31.8 | 29.9 |

| Neutral | 14.8 | 3.4 |

| It is riskier to have sex with a person who was recently incarcerated. | ||

| Agrees | 48.9 | 37.9 |

| Disagrees | 34.1 | 44.8 |

| Neutral | 17.0 | 17.2 |

aA five-point Likert scale was collapsed into three categories: agrees includes “strongly agree” responses, and disagrees includes “strongly disagree”

*p < 0.01; **p < 0.05

Table 3.

Multivariate models of the relationship between attitudes and norms with having other sexual partners while a partner is incarcerated

| Attitudes and norms | Had other sexual partners while partner was incarcerated | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| OR [95 % CI] | OR [95 % CI] | |

| Attitudes factorb | 2.89 [1.95–4.26]** | 2.56 [1.73–3.79]** |

| Riskier to have sex with a person who was recently incarcerated (attitude) | 1.24 [0.91–1.68] | 1.18 [0.84–1.67] |

| Friends would think it is ok if you had sex with someone else (injunctive norm) | 1.33 [0.97–1.83]* | 1.41 [1.0–1.98]* |

| Friends would go out with someone else (descriptive norm A) | 1.33 [0.99–1.8]* | 1.39 [0.96–2.0]* |

| Friends would NOT hide going out with someone else (descriptive norm B) | 1.24 [0.91–1.69] | 1.29 [0.92–1.82] |

**p < 0.05, *p < 0.10

aMultivariate analyses adjusted for participants’ age and sexual risk (multiple partners and unprotected sex with non-main partner)

bAttitudes and norms items have been standardized

Discussion

In this sample of women who had a main partner that was incarcerated, we found that having other sex partners during the incarceration was common and associated with several individual characteristics. In addition, norms and attitudes were associated with having other sex partners.

Our finding that half of the sample had other sex partners while their partner was incarcerated is consistent with previous research.20 Women who had other partners while their partner was incarcerated were more likely to be younger and engage in other risky sexual behaviors and non-injection drug use. Attitudes indicating approval with having other sex partners while a person’s partner is incarcerated were positively associated with having sex with other partners. Thus, participants viewed this behavior as acceptable, especially in situations where the partner may receive resources in exchange for the partnership.

When a partner is incarcerated, the emotional and material support they provided is gone as well.42 This lack of support and resources may persuade the non-incarcerated partner to seek other companionship to fill the gaps left behind by the partner. Further, stigma associated with having an incarcerated partner may prevent the partner on the outside from getting assistance from public or social services agencies.52 Thus, she may seek out other sex partners for economic resources.

Through semi-structured interviews, Gorbach and colleagues53 described a phenomenon called “separation concurrency”, which occurs when a person seeks other sex partners while the main partner is away as a result of situations like incarceration. They found that while many partners knew about the other partners, it was not openly discussed within the couple. In our study, approximately two thirds of the women who had other sex partners reported that their partner knew about the other partners. However, our study did not ascertain if the women themselves told their incarcerated partner or the partner found out through other social network members. Previous research has shown that concurrency is often viewed as socially acceptable within groups at high risk for HIV.41

Our study has shown that incarceration is a normative behavior. The majority of participants reported having ever been arrested or incarcerated. Personal incarceration has been linked to having sex partners with a history of incarceration.32 Participants own experiences may have shaped their attitudes and changed the structure of the social network with more favorable views towards having other partners and ultimately influenced their behavior.

In addition, over 60 % of the sample reported having someone (a person who was not the partner) in their social network who had been incarcerated. Having interactions with individuals with an incarceration history provides opportunity for norms to form. It is highly probable that participants have social network members who have been in a relationship with someone who was incarcerated. As a result, participants may have had the opportunity to discuss and observe these relationships. Having other partners while a partner is incarcerated may be viewed as a normative behavior if others seems to do this as well.

In our sample, women who did not have other sexual partners were more likely to resume sexual activity when their partner was released from jail or prison suggesting that some women who had other sex partners may have anticipated that their relationship with their incarcerated partner would end. Incarceration disrupts social networks and increased stress on a relationship; thus partnerships may dissolve.31

Approximately 43 % of the sample held the attitude that it was risky to have sex with someone who was incarcerated. Yet, of the 76 % of women who resumed sexual relationships with their partner upon release, only one third used condoms. Similar results have been previously reported.43 It is important to note that we did examine the relationships between attitudes and norms with having unprotected sex with partner after release. However, there was no significant association (data not shown). Examination of recent sexual risk behaviors reveals that unprotected sex with a main partner among women in our study is highly prevalent. It is promising that 50 % of the sample reported that their partner got tested for HIV before they reinitiated sex.

Unprotected sex may occur because partners want to re-establish their relationship and demonstrate trust upon a partner’s release.54 However, all of this may come at a price if the incarcerated partner or non-incarcerated partner has engaged in any risky drug and sex behaviors during the separation. Our study has shown that a large percentage of women have other partners when their partner is incarcerated. Women who reported other partners while a main partner was incarcerated also were more likely to currently have lower condom efficacy skills and were less likely to use condoms with casual partners.

This analysis has several limitations that should be noted. First, the data were cross-sectional so we are unable to ascertain a temporal relationship between having an incarcerated partner and participants’ attitudes and norms towards incarcerated sexual partners and own sexual risk behaviors. The questions focused on ever having a partner who was incarcerated for longer than 6 months in the relationships. We do not have data on how long ago the incarceration occurred and how long the relationship continued after the incarceration period. Some of the responses may be subject to recall bias if the respondent’s partner was incarcerated a long time ago. In addition, we do not know the full length of incarceration.

This is one of the first studies to date that has explored how attitudes and norms about incarcerated partners are related to sex behaviors when partner in incarcerated. Future research is needed to assess if attitudes and norms about partners’ incarceration are associated with STI and HIV status. Progress has been made in the prevention of HIV among inmates. For example, since 2008, the Baltimore City jails have offered HIV rapid testing to inmates on a voluntary basis.55 However, while attention to HIV prevention among incarcerated partners has greatly increased,56 more work focusing on non-incarcerated partners is needed. The study has shown that incarcerated individuals do not account for the entire link between HIV and incarceration; non-incarcerated partners also may introduce HIV/STIs to the relationship. Thus, prevention programs for the partners of incarcerated individuals are urgently needed.

One HIV prevention approach that optimizes the effect of attitudes and norms on behaviors is peer education. Through peer education programs, a select group of individuals disseminate HIV risk reduction information and resources as well as promote norms regarding risk reduction. Grinstead and colleagues57 utilized peer educators to promote condom use and HIV testing as well as to educate women with incarcerated male partners about the links between HIV and incarceration. Women who went through the intervention were more likely to get tested as well as have their partner get tested for HIV after the release.58 In addition, interventions designed for couples at pre- and post-release from prison are a mechanism to create personalized risk reduction plans and encourage HIV/STI testing prior to reunion. Finally, support programs for women whose partner is incarcerated are essential to assist in the mental and material costs endured during this time. This support can reduce the need to seek relations outside of the primary partnership, positively affecting attitudes, norms and behaviors that increase the risk of HIV.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute on Mental Health (grant no. R01 MH66810).

References

- 1.Roberts DE. The social and moral cost of mass incarceration in African American communities. Stanford Law Rev. 2004;56(5):1271–1305. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heigel CP, Stuewig J, Tangney JP. Self-reported physical health of inmates: impact of incarceration and relation to optimism. J Correct Health Care. 2010;16(2):106–116. doi: 10.1177/1078345809356523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan M. The prison setting as a place of enforced residence, its mental health effects, and the mental healthcare implications. Health Place. 2011; 17(5): 1061–1066. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Courtenay-Quirk C, Pals SL, Kidder DP, Henny K, Emshoff JG. Factors associated with incarceration history among HIV-positive persons experiencing homelessness or imminent risk of homelessness. J Commun Health. 2008;33(6):434–443. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson FS, Cleland CM, Chaple M, Hamilton Z, Prendergast ML, Rich JD. Substance use, mental health problems, and behavior at risk for HIV: evidence from CJDATS. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):459–469. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):840–846. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite RL, Arriola KR. Male prisoners and HIV prevention: a call for action ignored. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9 Suppl):S145–S149. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epperson MW, Khan MR, El-Bassel N, Wu E, Gilbert L. A longitudinal study of incarceration and HIV risk among methadone maintained men and their primary female partners. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):347–355. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9660-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jurgens R, Nowak M, Day M. HIV and incarceration: prisons and detention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:26. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudsen HK, Leukefeld C, Havens JR, et al. Partner relationships and HIV risk behaviors among women offenders. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):471–481. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosman J, Macgowan R, Margolis A, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and hepatitis in men with a history of incarceration. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(7):634–639. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820bc86c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruschak LM. HIV in prisonss, 2007–08. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. 2009: NCJ 228307.

- 13.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the Southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammett TM, Drachman-Jones A. HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, and incarceration among women: national and southern perspectives. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S17–S22. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218852.83584.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheyett A, Parker S, Golin C, White B, Davis CP, Wohl D. HIV-infected prison inmates: depression and implications for release back to communities. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):300–307. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seal DW, Margolis AD, Morrow KM, et al. Substance use and sexual behavior during incarceration among 18- to 29-year old men: prevalence and correlates. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):27–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manhart LE, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Sex partner concurrency: measurement, prevalence, and correlates among urban 18-39-year-olds. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(3):133–143. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent partnerships among rural African Americans with recently reported heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34(4):423–429. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epperson M, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Orellana ER, Chang M. Increased HIV risk associated with criminal justice involvement among men on methadone. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):51–57. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9298-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacGowan RJ, Margolis A, Gaiter J, et al. Predictors of risky sex of young men after release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(8):519–523. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grieb SM, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin CA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among urban African American high-risk women with main sex partners. AIDS Behav. 2011; 16(2): 323–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Tyndall MW, Patrick D, Spittal P, Li K, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Risky sexual behaviours among injection drugs users with high HIV prevalence: implications for STD control. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(Suppl 1):i170–i175. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werb D, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. HIV risks associated with incarceration among injection drug users: implications for prison-based public health strategies. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30(2):126–132. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comfort M, Grinstead O, McCartney K, Bourgois P, Knight K. “You cannot do nothing in this damn place”: sex and intimacy among couples with an incarcerated male partner. J Sex Res. 2005;42(1):3–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grinstead O, Zack B, Faigeles B. Reducing postrelease risk behavior among HIV seropositive prison inmates: the health promotion program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13(2):109–119. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.2.109.19737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grinstead OA, Faigeles B, Comfort M, et al. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk to primary female partners of men being released from prison. Women Health. 2005;41(2):63–80. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epperson MW, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Gilbert L. Examining the temporal relationship between criminal justice involvement and sexual risk behaviors among drug-involved men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):324–336. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9429-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(3):155–160. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan MR, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, et al. Timing and duration of incarceration and high-risk sexual partnerships among African Americans in North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(5):403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):100–113. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim A, Page-Shafer K, Ruiz J, et al. Vulnerability to HIV among women formerly incarcerated and women with incarcerated sexual partners. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(4):331–338. doi: 10.1023/A:1021148712866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Montague BT, Rich JD. Opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV in the criminal justice system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S49–S55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clear TR, Rose DR. Individual sentencing practices and aggregate social problems. In: Hawkins DF, Myers SLJ, Stone RN, editors. Crime control and social justice: the delicate balance. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2003. pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aral SO. Sexual network patterns as determinants of STD rates: paradigm shift in the behavioral epidemiology of STDs made visible. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(5):262–264. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braman D. Families and incarceration. In: Mauer M, Chesney-Lind M, editors. Invisible punishment: the collateral consequences of mass imprisonment. New York: The New Press; 2002. pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas JC, Thomas KK. Things ain’t what they ought to be: social forces underlying racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted diseases in a rural north carolina county. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(8):1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58(6):1015–1026. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. An examination of perceived norms and exchanging sex for money or drugs among women injectors in baltimore, MD, USA. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(1):47–50. doi: 10.1258/Ijsa.2007.007123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton A, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):465–476. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nunn A, Dickman S, Cornwall A, et al. Social, structural and behavioral drivers of concurrent partnerships among African American men in Philadelphia. AIDS Care. 2011; 23(11): 1392–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Blankenship KM, Smoyer AB, Bray SJ, Mattocks K. Black-white disparities in HIV/AIDS: the role of drug policy and the corrections system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4 Suppl B):140–156. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harman JJ, Smith VE, Egan LC. The impact of incarceration on intimate relationships. Crim Justice Behav. 2007;34(6):794–815. doi: 10.1177/0093854807299543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wildeman C, Western B. Incarceration in fragile families. Future Child. 2010;20(2):157–177. doi: 10.1353/foc.2010.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin K, Yang C, Sun CJ, Latkin CA. Results of a randomized controlled trial of a peer mentor HIV/STI prevention intervention for women over an 18 month follow-up. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1654–1663. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9943-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black CW. Multivariate data analysis: with readings. 4. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, et al. Intersecting epidemics—crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. multicenter crack cocaine and HIV infection study team. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(21):1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffman JA, Klein H, Eber M, Crosby H. Frequency and intensity of crack use as predictors of women’s involvement in HIV-related sexual risk behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58(3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costenbader EC, Astone NM, Latkin CA. The dynamics of injection drug users’ personal networks and HIV risk behaviors. Addiction. 2006;101(7):1003–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Browning SL, Miller RR, Spruance LM. Criminal incarceration dividing the ties that bind: black men and their families. J Afr Am Men. 2001;6(1):87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorbach PM, Stoner BP, Aral SO, Whittington WLH, Holmes KK. “It takes a village”: understanding concurrent sexual partnerships in seattle, washington. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(8):453–462. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Corbett AM, Dickson-Gomez J, Hilario H, Weeks MR. A little thing called love: condom use in high-risk primary heterosexual relationships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41(4):218–224. doi: 10.1363/4121809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beckwith CG, Nunn A, Baucom S, et al. Rapid HIV testing in large urban jails. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S184–S186. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rich JD, Wohl DA, Beckwith CG, et al. HIV-related research in correctional populations: now is the time. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):288–296. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grinstead O, Comfort M, McCartney K, Koester K, Neilands T. Bringing it home: design and implementation of an HIV/STD intervention for women visiting incarcerated men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(4):285–300. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.4.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grinstead Reznick O, Comfort M, McCartney K, Neilands TB. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention program for women visiting their incarcerated partners: the HOME project. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):365–375. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9770-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]