Abstract

Sex trafficking, trafficking for the purpose of forced sexual exploitation, is a widespread form of human trafficking that occurs in all regions of the world, affects mostly women and girls, and has far-reaching health implications. Studies suggest that up to 50 % of sex trafficking victims in the USA seek medical attention while in their trafficking situation, yet it is unclear how the healthcare system responds to the needs of victims of sex trafficking. To understand the intersection of sex trafficking and public health, we performed in-depth qualitative interviews among 277 antitrafficking stakeholders across eight metropolitan areas in five countries to examine the local context of sex trafficking. We sought to gain a new perspective on this form of gender-based violence from those who have a unique vantage point and intimate knowledge of push-and-pull factors, victim health needs, current available resources and practices in the health system, and barriers to care. Through comparative analysis across these contexts, we found that multiple sociocultural and economic factors facilitate sex trafficking, including child sexual abuse, the objectification of women and girls, and lack of income. Although there are numerous physical and psychological health problems associated with sex trafficking, health services for victims are patchy and poorly coordinated, particularly in the realm of mental health. Various factors function as barriers to a greater health response, including low awareness of sex trafficking and attitudinal biases among health workers. A more comprehensive and coordinated health system response to sex trafficking may help alleviate its devastating effects on vulnerable women and girls. There are numerous opportunities for local health systems to engage in antitrafficking efforts while partnering across sectors with relevant stakeholders.

Keywords: Vulnerable populations, Public health, Gender-based violence, Forced sexual exploitation, Sex trafficking, Social determinants of sex trafficking, Trafficking-related health problems, Access to health care, Health policy

Introduction

A human rights violation, trafficking for the purpose of forced sexual exploitation, known as sex trafficking, is a widespread form of human trafficking occurring in all regions of the world.1 Though trafficking prevalence figures vary widely, the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that there are approximately 21 million “victims of forced labor” worldwide at any given time. Included in this estimate are the 4.5 million victims of forced sexual exploitation, 98 % of whom are estimated to be women and girls.2

Sex trafficking is defined under international law by the United Nations (UN) Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability” for commercial sex or other forms of sexual exploitation. This protocol further stipulates that sexual exploitation involving a child (<18 years) is considered trafficking, regardless of the means.3

A form of gender-based violence, sex trafficking is thought to primarily affect women and girls, posing serious detrimental physical and psychological health risks.4 – 6 Recent studies among sex-trafficked women and girls have demonstrated associations between sex trafficking and increased prevalence of HIV, as well as other sexually transmitted infections.7 – 9 The wide range of negative health outcomes, and the threat of increased HIV transmission, suggests that sex trafficking is a public health issue of global concern. Furthermore, studies in the USA among survivors of sex trafficking suggest that up to 50 % of victims seek medical care while in their trafficking situation.10 , 11 These negative health implications and the health-related encounters that give the health system unique access to victims also underscore the need to better understand the potential antitrafficking role of the health sector, an area still not well developed in the literature. In particular, little is known about the current roles of local health systems in mitigating the negative effects of sex trafficking on the health and well-being of individuals and communities.

Through comparative case studies, we used a public health lens to examine the local context in which sex trafficking of women and girls occurs in eight cities around the world. Together, these cases describe key social determinants of sex trafficking, the current responses of local health systems to sex trafficking, and potential roles for local health systems in addressing this form of trafficking in the future.

Methods

Case Study Site Selection

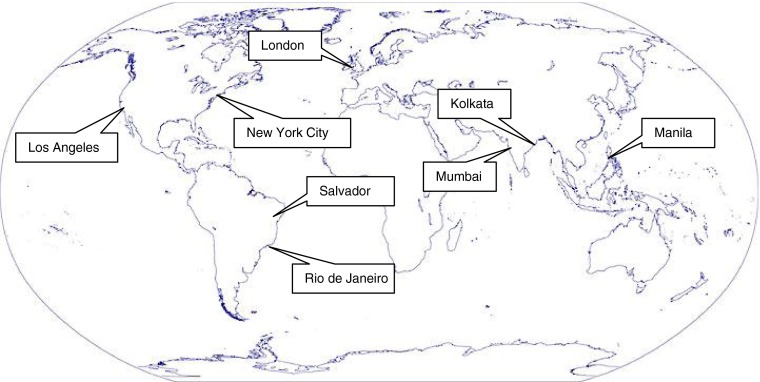

We completed eight case studies during a 12-month study timeframe (Fig. 1). Case study methodology allowed for an inductive, exploratory approach to examining sex trafficking. The total number of case studies was consistent with social science case study literature, which proposes 4–10 cases for informing development of conceptual frameworks.12 Using cities as the primary unit of analysis, we reviewed many potential candidate sites. Ultimately, we selected cities that had a significant sex trafficking trade, as well as public health infrastructure that would allow us to study the health system role in addressing trafficking. Other site selection criteria included access to local social scientists, sufficient security/safety for the research team, and a demonstrated commitment by the national government to address sex trafficking. We relied on existing data and indicators from widely available, reputable sources (e.g., US Department of State, World Health Organization, World Bank) to stratify candidate countries, then cities within these countries. Final site selection was an iterative process guided by the principle of theoretical sampling through which we also attempted to capture complementary theoretical domains13 on sex trafficking (e.g., developed versus developing country, predominance of domestic versus international trafficking, origin versus destination site).

Figure 1.

Map of case study sites.

Participants

A total of 277 respondents from health and non-health sectors were interviewed (Table 1). Researchers developed a list of potential interviewees in each city by way of web-based searches of media outlets, organizational reports, health journals, and government documents. These potential participants were contacted regarding the study with requests for an interview and referrals to colleagues engaged in local antitrafficking work. This respondent-driven snowball sampling allowed for identification of key antitrafficking stakeholders from various sectors, representing a wide range of occupations and organization types. Snowball sampling continued until theoretical saturation was attained in each city. Theoretical saturation was reached when the paired researchers jointly determined that additional interviews (either in terms of number or type of participant) would be unlikely to yield any new data.14 All participants provided verbal informed consent and their anonymity was assured. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners Healthcare (Boston, MA, USA) and exempted from further review.

Table 1.

Number of participants interviewed per case study site (N = 277), sampled occupations, and sampled organization types

| No. of participants (%) (N = 277) | Occupation types | Organization types | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manila | 51 (18.4) | Physician | Health care organization |

| Kolkata | 49 (17.7) | Nurse | Social service organization |

| Salvador | 41 (14.8) | Mental health provider | Advocacy |

| Rio de Janeiro | 37 (13.3) | Social worker | Academic or research |

| Mumbai | 34 (12.3) | Community outreach worker | Government (health) |

| New York City | 23 (8.3) | Program director | Government (nonhealth) |

| Los Angeles | 21 (7.6) | Administrator | Foundation, philanthropy |

| London | 21 (7.6) | Researcher | |

| Government official | |||

| Foundation, philanthropy officer | |||

| Law enforcement official | |||

| Legal professional | |||

| Other | |||

Interviews

Eight health researchers, trained in case study methodology and working in pairs to minimize potential single-investigator bias, conducted the interviews between November 2008 and August 2009. Using the UN definition of sex trafficking, a semistructured interview guide was used to elicit respondents’ perceptions of the scope and key determinants of sex trafficking in their city; the current local health system response; the barriers to greater health sector participation in antitrafficking activities; and the potential opportunities for the local health system in antitrafficking efforts. The interview guide includes semistructured and open-ended questions to allow both the participant and interviewer freedom to explore new themes as they arise in the course of the conversation. In the two Brazil cases, an established professional interpreter accompanied the research team. With rare exception, all interviews were conducted in-person. Interviews lasted 60 min on average, but length varied depending on the direction of the interview and the extent of translation required. Researchers took notes during the interviews and, with few exceptions, audiorecorded all interviews for transcribing purposes. All audio files were downloaded to a secured, encrypted laptop computer at the end of the interview day and deleted from the portable recording device. The audio files were transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team, or, as in the Brazil interviews, transcribed verbatim in Portuguese and subsequently translated into English by the established professional interpreter. All transcripts were reviewed for accuracy with the audio files by at least one other team member before being finalized.

Data Analysis

Our analysis of the interview transcripts was both iterative and collaborative. Research team members triangulated interview transcripts with the audio files and notes taken during the interviews. We took a hybrid approach to developing a code book, one that has been described by Bradley et al. as an “integrated approach” that “employs both inductive (ground up) development of codes, as well as a deductive organizing framework for code types (start list).”13 Once the research team reviewed a sizable subset of the interviews, it developed, over several iterations, a code book that could be used across the eight cities to organize the data. Pairs of researchers were involved in coding the interview transcripts for each case, to strengthen inter-rater reliability. Research teams also met to discuss similarities and differences in the major themes that emerged from the transcripts and to resolve any discrepancies in their findings. This constant iteration and use of multiple researchers provided opportunities to debate interpretations of interviews, and to thoughtfully begin to establish the logic (i.e., establishing the “chain of evidence”) for case key finding outlines. As the project evolved, the research team met often to discuss intercase common themes and differences, and to discuss any difficulties in coding, or in approaches to identifying emerging themes in the individual cases. Qualitative research software (NVivo 9, QSR International) was used to organize data for each case study site.

Results

While mindful of the various and specific contexts of each of the case study cities, we identified several cross-case thematic findings. These findings relate to the scale and scope of trafficking, key determinants of sex trafficking, barriers to health workers’ participation in antitrafficking efforts, and future opportunities for local health systems to address sex trafficking.

Uncertain Prevalence of Sex Trafficking

The difficulty in determining the scope of sex trafficking was identified as a major theme in all eight cities. Many respondents commented that sound methodologies for accurately estimating the prevalence of sex trafficking have yet to be developed. Respondents attributed some of the difficulty in developing these methodologies to the hidden nature of sex trafficking. Respondents further noted the lack of centralized databases for tracking victims as contributing to the difficulty in reliably estimating the extent of sex trafficking. Several respondents voiced concern over the wide range of published prevalence figures, cautioning that these estimates are mired by competing definitions of sex trafficking, discordance in the perceived agency of women, challenges in identifying victims, and hidden political agendas.

The majority of respondents believed that current estimates undercount the true number of victims; many referring to these estimates as representing “the tip of the iceberg.” The reasons suggested for this undercounting included victims’ reluctance to identify themselves to authorities as well as their inability to recognize their own victimization. Several respondents noted that the long-term exposure to physical threats and psychological manipulation instills fear in trafficking victims and facilitates the trafficker’s ability to exert control over victims. Fear of retaliation against them or their families may prevent victims from attempting escape as well as deter them from reporting or seeking assistance both during and after exiting the trafficking situation. Respondents also identified victims’ shame, denial, fear of authorities (e.g., possible deportation, skepticism about victims’ claims, or judgmental attitudes), and dependence on or traumatic bonding with their traffickers as barriers to self-reporting.

Key Determinants of Sex Trafficking

Respondents identified several key determinants of sex trafficking. Child sexual abuse was viewed as a major determinant of sex trafficking in all eight cities. Family dysfunction and early exposure to violence in the home were also frequently reported as trafficking determinants. Respondents explained that these unhealthy relationships and experiences in childhood result in multiple factors at the individual level, such as low self-esteem, need for affection, and inappropriate sexual boundaries, that increase an individual’s vulnerability to sex trafficking. Financial insecurity, lack of formal education, and lack of viable alternative economic opportunities were also described as important determinants. Respondents believed that these combined economic factors fuel the migration of women and girls out of their rural villages in search of work and/or education, a process during which they are vulnerable to being lured or coerced into sex trafficking. Particularly in the Indian case studies, the role of family poverty in fostering the sex trafficking of girls was critical. In most case sites, respondents believed that family members, some unwittingly and some knowingly, play a role in the trafficking process.

In some cities, societal and cultural norms that reinforce inequalities were also viewed as facilitators of sex trafficking. Societal-level factors appear to play particularly important roles in the cases of India and Brazil. Many respondents, notably in Rio and Salvador, made specific reference to the sexual objectification of women and girls as a form of gender inequality that normalizes sexual exploitation and facilitates sex trafficking. Respondents further explained that this objectification leads to the early socialization of women and girls who, by adopting the view of themselves as sexual objects, become prime targets for exploitation in the commercial sex industry. Respondents also cited the high demand among men for commercial sex and the profitability of the commercial sex trade as important and often overlooked key trafficking determinants. Furthermore, the complex interplay of determinants facilitating the trafficking of women and girls is compounded in the legal sex work industries of India and Brazil, where respondents suggested that some law enforcement officials are complicit in the sex trafficking trade of minors. In Kolkata, social discrimination against darker-skinned individuals and lower-caste individuals also serve as risk factors for sex trafficking. A similar discrimination was described in Rio and Salvador against darker-skinned individuals and those who live in poor urban shanty towns (favelas) or in poor rural communities.

Weak Response of Local Health Systems

Respondents described a myriad of health problems either associated with sex trafficking or consequential to the poor working and living conditions of sex-trafficked victims (Table 2). However, respondents in all eight cities characterized their local health system responses as weak and limited. Although public health facilities were believed to provide the majority of health care for victims, especially in emergency situations, many respondents remarked that local governments had not developed well-coordinated systems of health care for sex trafficking victims.

Table 2.

Reported health problems of sex-trafficked victims

| Sexually transmitted infections |

| Physical injuries/burns |

| Anxiety/post-traumatic stress disorder |

| Unsafe abortions |

| Substance abuse |

| HIV/AIDS |

| Depression/suicide |

| Sexual violence |

| Rape/gang rape |

| Malnutrition |

| Somatic symptoms (skin and gastrointestinal disorders) |

| Sleep deprivation |

| Lack of immunization |

| Dental disease or injury |

| Tuberculosis |

In all eight cities, nongovernmental organization (NGO) service providers were perceived as attempting to fill this gap by either providing or facilitating access to healthcare services. For example, several respondents in the cases of New York and India noted that NGO service providers rely heavily on personal contacts in healthcare facilities to secure illness-related episodic care for former victims. In many of the cities, respondents were able to identify various nonprofit free health clinics, community health clinics, mobile health clinics, and emergency departments as local resources for accessing care, but believed that no single facility was designed to meet all the health and mental health needs of this population.

Despite the efforts of NGO service providers and a small number of dedicated healthcare workers in each city, the victims’ lack of access to health care was viewed as being a significant gap and was a major concern among respondents. In particular, the absence of culturally sensitive mental health services for trafficking victims was described as a major gap in services in all eight cities. Furthermore, in Kolkata and Mumbai, many respondents expressed the need for health care for the children of trafficking victims and commercial sex workers.

Barriers to Greater Health System Participation

Respondents reported that the hidden nature of trafficking dramatically restricts victims’ access to healthcare services while they are in trafficking situations. Many respondents also noted that the inhibited health-seeking behavior of victims (and former victims) acts as a barrier to a greater health system response. Victims were believed to refrain from seeking care due to fear of discriminatory treatment, fear of being reported to immigration officials, and fear that they were either not entitled to or could not afford health care. Other victims were reportedly deterred by the long wait times or restricted hours of operation at health facilities. Moreover, many respondents acknowledged that when victims (and former victims) do present to health facilities for illness-related episodic care, their reluctance or inability to disclose their situation further limits the response of local healthcare systems. Respondents explained that the health system’s inability to identify them as victims of trafficking, while multifactorial, also leads to the failure in recognizing the full extent of their health and mental health needs at the time of presentation.

Respondents described a general “reluctance” or “disinterest” within the health system and among health providers to address the broader issue of interpersonal sexual violence and commercial sexual exploitation. They attributed this reluctance to a variety of factors such as health providers’ low level of awareness of trafficking, high patient case load, fear of breaching patient confidentiality, fear of compromising patient safety, and fear of retribution by the traffickers. In the cases of Brazil, Philippines, and India, some respondents noted that health providers’ tendency to either avoid or ignore the overarching problem of violence against women and girls is a product of gender inequalities that exist in the cultural and social norms—norms from which health providers are not immune. Many respondents in these cities commented that health providers can harbor discriminatory attitudes towards women and girls, especially those suspected of engaging in commercial sex. These attitudes reportedly result in punitive and insensitive treatment of victims. In Mumbai and Kolkata, respondents perceived that hospital workers prejudge women in prostitution and treat them less favorably than other patients. In Manila and Rio, multiple key informants reported widespread humiliating treatment of unmarried women who present for reproductive health problems and outright hostility toward women who present for care following complications from unsafe abortions. In addition, several respondents in the Brazil cases noted that some healthcare workers’ negative attitudes toward certain patients (e.g., poor, Black women) can have deleterious effects on women’s access to, and experiences with, health care. Respondents expressed concern that these attitudes among health providers further discourage victims from disclosing their experiences, thereby interfering with their ability to obtain care and referrals tailored to their specific needs.

At the systems level, respondents cited several barriers to greater health system participation in antitrafficking efforts: the dismissal of trafficking as a public health issue, the absence of curricular offerings on trafficking in health professional schools, the dearth of trafficking-related training programs for practicing health workers, the lack of streamlined referral mechanisms to social services for victims, the constraints placed on resources by overburdened healthcare systems, the institutional biases that engender lower quality health care for poor women and girls, and the emphasis placed on a biomedical, rather than holistic, approach to health in medical training.

At the national and policy levels, the lack of participation of health officials in antitrafficking policymaking was noted in several cities. In London, Manila, Kolkata and Mumbai, some respondents argued that the practice of police raids in red-light districts undermine the ability of NGOs and healthcare workers to negotiate access to brothels and provide health care for victims.

Discussion

The present case studies indicate that a preponderance of antitrafficking stakeholders believe currently available prevalence figures are inaccurate and reflect an underestimation of the scope of sex trafficking. They also identify a wide range of factors—from family poverty and child sexual abuse to gender inequality—that function as determinants of sex trafficking. Operating at the macro- and microlevels of the socioecological model of health, these sociocultural and economic factors can have devastating effects on the health and psychosocial development of girls, placing them at increased risk of sex trafficking and related negative health outcomes. These findings are consistent with extant literature on sex trafficking and health.15 – 18 Additionally, our study corroborates trafficking studies that document the myriad harmful physical and psychological effects of sex trafficking on victims.19 – 21

Our case studies further suggest that local health systems have been slow to respond to sex trafficking. In these eight cities, health workers’ awareness of sex trafficking was low, as was their knowledge of how to proceed when encountering victims. In addition, we found that many health professionals are reluctant to actively pursue victim identification and to intervene in trafficking situations, further impeding the health sector’s contribution to local antitrafficking efforts. Furthermore, many gaps in health services for victims remain unaddressed. Comprehensive, coordinated systems to meet the full range of trafficking victims’ health needs were absent in the eight cities, and the lack of mental health services for victims was described as the most acute health-related gap. While sex trafficking and the available local health resources may differ from one city to another, antitrafficking stakeholders in all eight cities welcomed greater health sector participation in continued antitrafficking efforts.

Recommendations for Antitrafficking Role of the Health Sector

Our study proposes an expanded antitrafficking role for local health systems. In addition to providing illness-related episodic care for trafficking victims, local health systems can participate in five areas: (1) prevention, (2) victim identification, (3) trauma-informed health and mental health care, (4) rehabilitation and referral, and (5) advocacy and policy engagement.

Prevention

Health workers could embed trafficking prevention strategies into existing disease prevention and women’s health programs, especially in rural villages and other source areas, to allow for early identification of and intervention for women and girls at risk of trafficking. Similarly, in more developed health systems, health professionals could partner with community and school-based health educators and providers to raise public awareness on this issue as a means of prevention for at risk groups. Prevention strategists should consider the specific factors that facilitate sex trafficking locally and the effects of these on the psychosocial development of girls when designing their prevention programs. Given that many respondents articulated that high demand for commercial sex fuels the sex trafficking of women and girls, prevention strategies designed to influence the psychosocial development of boys to reduce their future potential as buyers would also be an important approach. Furthermore, the medical and public health communities could draw on the lessons and successes of child abuse and domestic violence programs in order to inform the development of comprehensive, proactive, and effective trafficking prevention strategies.

Victim Identification and Trauma-Informed Care

Greater investments could be made in trafficking competency programs for health workers, including physicians, nurses, midwives, community health workers, school-based nurses, and other allied health professionals. Such programs should aim to train health workers as first responders for victims presenting to health facilities by providing them with the skills necessary for victim identification and trauma-informed care, and suggesting guidelines for safe interventions in trafficking situations. The ability of health providers to demonstrate a sensitivity to and understanding of the complexity of the physical and psychological trauma experienced by this population may over time increase the likelihood of trafficking victim disclosures in the health setting. This would in turn allow health providers the opportunity to recognize and address the full spectrum of their acute and long-term health and mental needs. Furthermore, introducing trafficking-related curricula at health professional schools and postgraduate clinical training programs may also be an effective strategy for engaging future generations of health professionals in antitrafficking efforts.

Rehabilitation and Referral

Rehabilitation is as important to the healing process as trauma-informed care. The health community could partner with local antitrafficking stakeholders and mental health providers to develop coordinated, streamlined mechanisms of referral to mental health, social services, residential programs, and legal services for trafficking victims, with a preference whenever possible for services specifically designed to meet the needs of this population. A multilateral referral system would promote stronger collaborations among the various agents facilitating victim rehabilitation and social reintegration, and potentially render these integrated efforts more effective.

Advocacy and Policy Engagement

Finally, advocacy and public policy have historically been crucial components in promoting the sustainability and effectiveness of antiviolence movements within the health sector.22 Health providers active in health professional associations and medical societies could advocate for the official recognition of sex trafficking as an important public health issue. Such efforts would lay the groundwork for the health sector to increasingly participate in antitrafficking policymaking at the local and national levels, ensuring that the public health perspective is incorporated into future antitrafficking initiatives.

Study Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of our case studies precluded a longitudinal examination of this complex and dynamic phenomenon. Moreover, our a priori decision to focus on women and girls limited our ability to examine the issue of sex trafficking among male and transgender counterparts, which is known to occur, but perhaps erroneously thought to be a minor form of sex trafficking due to a lack of research. Furthermore, due to concerns for safety and the potential for retraumatization, we elected not to interview sex trafficking victims for this study. The lack of interviews with victims could potentially affect study results related to trafficking determinants or how victims perceive and access health services. In London, we were unable to interview National Health Service (NHS) healthcare workers during the study timeframe. While we made a concerted effort to interview non-government employed (non-NHS) health professionals, the paucity of health interviews in London limits our ability to directly capture this cohort’s perspectives. Finally, it is plausible that social desirability bias (e.g., portraying their city in the most favorable light or the least favorable light to draw further attention) could have affected the responses of some respondents.

Conclusions

Our study highlights the unmet need and significant opportunity for local health systems to assume a more active role in antitrafficking work. Recognizing sex trafficking as a pervasive form of gender-based violence with major health, mental health, and public health implications is crucial. In addition, by developing a greater understanding of the potential roles of local health systems in mitigating the devastating effects of sex trafficking, we may be able to catalyze greater health sector participation in the global efforts to eliminate this form of gender-based violence. Future studies should focus on identifying and developing best practices in the field to begin establishing a global framework of sex trafficking through the public health lens.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from Humanity United, Redwood City, CA, USA. The funding organization provided helpful, nonbinding study design suggestions, but had no role in the conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. A grant from Give Way to Freedom, Essex Junction, VT, USA, also supported the preparation of the manuscript; this funding organization had no role in the conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions made by Jay Silverman and Michele Decker, the indispensible field support provided by Peter Lenny, Kena Silva, and Sylvia Lichauco, and the research assistance provided by Julie Barenholtz, Christina Martin, Kathryn Conn, and Hannah Harp.

References

- 1.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime . Trafficking in persons: global patterns. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Labour Organization. ILO global estimate of forced labour: results and methodology. 2012. ILO: Geneva. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---declaration/documents/publication/wcms_182004.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2013

- 3.United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. Protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, 2000. http://www.uncjin.org. Accessed 15 Mar 2010

- 4.World Health Organization. Violence against women. Fact sheet No 239, November 2009. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en. Accessed 15 Mar 2010

- 5.Zimmerman C, Hossain M, Yun K, et al. The health of trafficked women: a survey of women entering posttrafficking services in Europe. Am J of Publ Health. 2008;98(1):55–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.108357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Organization for Migration . Caring for trafficked persons: guidance for health providers. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Patel V, Raj A. HIV Prevalence and predictors among rescued sex-trafficking women and girls in Mumbai, India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(5):588–593. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243101.57523.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Maheshwari A, Willis BM, Raj A. HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women. JAMA. 2007;298:536–542. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Gupta J, Dharmadhikari A, Seage GR, Raj A. Syphilis and hepatitis B Co-infection among HIV-infected, sex-trafficked women and girls, Nepal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(6):932–934. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.080090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Family Violence Prevention Fund. Turning pain into power: trafficking survivors’ perspectives on early intervention strategies. San Francisco, CA: Family Violence Prevention Fund; 2005.

- 11.Baldwin SB, Eisenman DP, Sayles JN, Ryan G, Chuang KS. Identification of human trafficking victims in health care settings. Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(1):36–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhardt K. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev. 1989;14(4):532–550. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse E. Theoretical saturation. In: Lewis-Beck M, et al., Editors. Encyclopedia of social science research methods, Sage Publications, 2004. Available at: http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/socialscience/n1011.xml. Accessed 13 Sept 2013

- 15.Silverman J, Decker M, Gupta J, et al. Experiences of sex trafficking victims in Mumbai, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;97(3):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis BM, Levy BS. Child prostitution: global health burden, research needs, and interventions. Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1417–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajic-Veljanoski O, Stewart DE. Women trafficking into prostitution: determinants, human rights and health needs. Transcult Psychiatry. 2007;44(3):338–358. doi: 10.1177/1363461507081635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huda S. Sex trafficking in South Asia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94(3):374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta J, Raj A, Decker MR, Reed E, Silverman JG. HIV vulnerabilities of sex-trafficked Indian women and girls. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutsumi A, Izutsu T, Poudyal AK, Kato S, Marui E. Mental health of female survivors of human trafficking in Nepal. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1841–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman C, Yun K, Shvab I, et al. The health risks and consequences of trafficking in women and adolescents: findings from a European study. London, UK: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA. History of violence as a public health issue. AMA Virtual Mentor. 2009;11(2):167–172. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2009.11.2.mhst1-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]