Background: 3-Ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenases catalyze the 1,2-desaturation of 3-ketosteroids.

Results: First structures of the enzyme from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1, combined with site-directed mutagenesis, clarify its catalytic mechanism.

Conclusion: Tyr487 and Gly491 promote keto-enol tautomerization, whereas Tyr318/Tyr119 and FAD abstract a proton and hydride ion, respectively.

Significance: This study is an important step toward tailoring the enzyme for steroid biotransformation applications.

Keywords: Cholesterol Metabolism, Crystal Structure, Dehydrogenase, Enzyme Mechanisms, Flavoproteins, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, 3-Ketosteroid, Rhodococcus erythropolis, Rossmann Fold

Abstract

3-Ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenases are FAD-dependent enzymes that catalyze the 1,2-desaturation of 3-ketosteroid substrates to initiate degradation of the steroid nucleus. Here we report the 2.0 Å resolution crystal structure of the 56-kDa enzyme from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 (Δ1-KSTD1). The enzyme contains two domains: an FAD-binding domain and a catalytic domain, between which the active site is situated as evidenced by the 2.3 Å resolution structure of Δ1-KSTD1 in complex with the reaction product 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione. The active site contains four key residues: Tyr119, Tyr318, Tyr487, and Gly491. Modeling of the substrate 4-androstene-3,17-dione at the position of the product revealed its interactions with these residues and the FAD. The C1 and C2 atoms of the substrate are at reaction distance to the N5 atom of the isoalloxazine ring of FAD and the hydroxyl group of Tyr318, respectively, whereas the C3 carbonyl group is at hydrogen bonding distance from the hydroxyl group of Tyr487 and the backbone amide of Gly491. Site-directed mutagenesis of the tyrosines to phenylalanines confirmed their importance for catalysis. The structural features and the kinetic properties of the mutants suggest a catalytic mechanism in which Tyr487 and Gly491 work in tandem to promote keto-enol tautomerization and increase the acidity of the C2 hydrogen atoms of the substrate. With assistance of Tyr119, the general base Tyr318 abstracts the axial β-hydrogen from C2 as a proton, whereas the FAD accepts the axial α-hydrogen from the C1 atom of the substrate as a hydride ion.

Introduction

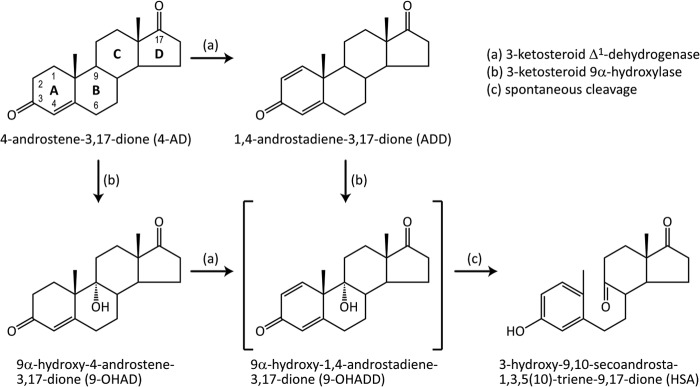

3-Ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase (Δ1-KSTD; 4-ene-3-oxosteroid:(acceptor)-1-ene-oxireductase; EC 1.3.99.4)3 is a FAD-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the introduction of a double bond into the C1-C2 position of the 3-ketosteroid A-ring (Fig. 1). The enzyme can dehydrogenate a wide variety of 3-ketosteroids, but not 3-hydroxysteroids, and has a preference for substrates unsaturated at the C4-C5 position, such as 4-androstene-3,17-dione (4-AD), 9α-hydroxy-4-androstene-3,17-dione, or 4-pregnene-17α,21-diol-3,11,20-trione (cortisone) (1, 2). Δ1-KSTDs are found in many steroid-degrading bacteria, particularly in those belonging to the genera Arthrobacter, Comamonas, Mycobacterium, and Rhodococcus (formerly Nocardia) (3, 4). They are, together with 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase, essential for the opening of the steroid B-ring of the key intermediate 4-AD (Fig. 1), which initiates the degradation of the steroid ring system (4–6).

FIGURE 1.

Degradation steps of 3-ketosteroids catalyzed by Δ1-KSTD and 3-ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase. The key metabolic compound 4-AD is converted into the unstable intermediate 9-OHADD, which undergoes spontaneous, nonenzymatic B-ring cleavage and A-ring aromatization to form HSA. See main text for further information.

The dehydrogenation catalyzed by Δ1-KSTD proceeds via direct elimination of two hydrogen atoms from its substrate, instead of via hydroxylation followed by dehydration (1, 7, 8). As determined using isotope-labeled substrates, the stereochemistry of the dehydrogenation appeared to proceed preferentially via a trans-diaxial elimination of the α-hydrogen of the C1 atom and the β-hydrogen of the C2 atom of the 3-ketosteroid substrate (9–11). Such a mechanism is also observed in the activity of acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenases (12, 13). Δ1-KSTDs catalyze the exchange of the alkali-labile hydrogen at the C2 atom of their substrates under conditions that inhibit enzyme turnover (9–11). This observation suggests that the enzyme-catalyzed dehydrogenation more likely follows a stepwise unimolecular elimination conjugate base (E1cB) mechanism, in which departure of the first hydrogen atom precedes that of the second hydrogen accompanied by the formation of an intermediate. A concerted bimolecular elimination (E2) mechanism, in which the two hydrogens depart simultaneously without the formation of any intermediate, was considered less likely. Therefore, catalysis by Δ1-KSTD was proposed to proceed via a two-step mechanism, initiated by the interaction of the C3 carbonyl group of the 3-ketosteroid substrate with an electrophile to promote labilization of the C2 hydrogen atoms. Subsequent abstraction of a proton from the C2 atom by a general base was proposed to result in either an enolate or a carbanionic intermediate, after which a double bond is formed between the C1 and C2 atoms in synchrony with hydride transfer from the C1 atom of the substrate to the flavin coenzyme (9–11). This proposed mechanism is in contrast to the dehydrogenation catalyzed by acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenases, which proceeds via a concerted removal of the eliminated hydrogens (12, 13).

Based on chemical modification, mutagenesis, and kinetics experiments, several amino acid residues of the Δ1-KSTD from Rhodococcus rhodochrous (formerly Nocardia corallina) were identified as important for catalytic activity, including one or two histidines, an arginine, and Tyr121, and several other residues were shown to be important for binding of the steroid substrates, such as Tyr104 and Tyr116 (14, 15). Moreover, mutagenesis studies on the Δ1-KSTD isoenzyme 2 from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 (Δ1-KSTD2) have shown that Ser325 and Thr503 are crucial for catalysis (5).

In R. erythropolis SQ1, three Δ1-KSTD isoenzymes have been found: Δ1-KSTD1 (16), Δ1-KSTD2 (5), and Δ1-KSTD3 (2). Previously, we described the purification, crystallization, and preliminary x-ray crystallographic analysis of Δ1-KSTD1 (17). Here, we report crystal structures of the enzyme in the unliganded form and in complex with the reaction product 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione (ADD). The structures provide insight into the active site of the enzyme and allowed us to assign its catalytic residues, which, interestingly, include three tyrosines. To further investigate their role, these tyrosines were mutated to phenylalanines, and the kinetic properties of the produced mutants were studied. These results enabled us to identify the roles of the amino acid residues involved in catalysis and to clarify the catalytic mechanism of Δ1-KSTD.

The information presented here may allow manipulating the catalytic properties of the enzyme to improve it for application in the pharmaceutical steroid industry. Furthermore, the steroid catabolic activity of steroid-degrading pathogenic bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Rhodococcus equi is frequently associated with their pathogenicity (18, 19). In particular, cholesterol degradation appeared to be essential for the survival of M. tuberculosis in the normally adverse environment of the host macrophages (19, 20). For this purpose, M. tuberculosis H37Rv contains a large gene cluster coding for enzymes catalyzing cholesterol degradation, including a gene for Δ1-KSTD (Rv3537) (19) that is important for its pathogenicity (21). Thus, these first three-dimensional structures of a Δ1-KSTD may facilitate the design of inhibitors that may be developed into efficacious drugs to combat pathogenic bacteria.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

A protocol for Δ1-KSTD1 expression has been established (2), as well as a procedure for its purification (17). In brief, Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) cells harboring the pET15b-kstD1 plasmid (2) were grown at 290 K. N-terminally His-tagged Δ1-KSTD1 was overexpressed by induction with 100 μm isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 48 h. After cell lysis, Δ1-KSTD1 was purified by immobilized Ni2+ affinity chromatography (HisTrap HP; GE Healthcare), followed by anion exchange chromatography (Resource Q; GE Healthcare) and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare). The purified Δ1-KSTD1 (in 25 mm bicine (N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine) buffer, pH 9.0, 100 mm NaCl, and 10% (v/v) glycerol) was concentrated to 50 mg ml−1 using an Amicon Ultra-4 30K filter (Millipore) and freeze-stored at 253 K until usage. All chromatography experiments were performed using an ÄKTAexplorer (GE Healthcare). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad), with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Protein purity was monitored by Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE.

Protein Crystallization

Δ1-KSTD1 was crystallized using the sitting drop, vapor diffusion method at room temperature (17). Typically, 0.30-μl drops comprising 0.15 μl of protein sample (15 mg ml−1 protein) mixed with 0.15 μl of reservoir solution (2% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 400, 0.1 m HEPES were equilibrated against wells containing 50 μl of the reservoir solution. Brightly yellow, rectangular crystals grew in 5–7 days to maximal dimensions of ∼100 × 100 × 300 μm3. Because of the low solubility of ADD in aqueous solution, protein samples were incubated with ADD powder (Steraloids Inc.) for 3 h on ice, prior to the cocrystallization experiments.

X-ray Data Collection and Processing

Before x-ray diffraction data collection, Δ1-KSTD1 crystals were transferred for 5 s to a cryoprotection solution (reservoir solution with 40% (w/v) sucrose added), followed by a 1-s transfer to a 1:1 solution of paraffin oil and paratone-N and flash cooling in liquid nitrogen (17). Δ1-KSTD1 crystals with bound ADD (Δ1-KSTD1·ADD) were cryoprotected in a similar way, except that both above solutions were saturated overnight with ADD powder. X-ray diffraction data from both Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD crystals were collected at 100 K on beam-line ID14-1 (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France) using an ADSC Quantum Q210 detector. Data sets comprising 450 and 550 frames with an oscillation range per frame of 0.2° were recorded from Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD, respectively, at a wavelength of 0.93340 Å. All data sets were processed and integrated using the program XDS (22) and scaled and merged with the program SCALA (23) from the CCP4 package (24).

Structure Determination and Refinement

The initial phases of Δ1-KSTD1 were obtained using multiwavelength anomalous dispersion data collected from a Pt-derivatized crystal, and a complete model for the protein was obtained (17). This model was subjected to rigid body refinement with the program Refmac5 (25) from the CCP4 package using native diffraction data of Δ1-KSTD1. The resulting model was then refined manually using the visualization program COOT (26). Water and ligand molecules were added to the model, manually checked, and refined against sigma-A-weighted 2Fo − Fc maps (27). The final model of Δ1-KSTD1 was obtained after several rounds of local real space refinement in COOT and overall restrained refinement in Refmac5. The same protocol was used to prepare the final model of Δ1-KSTD1·ADD. The atomic coordinates and experimental structure factor amplitudes have been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank with Protein Data Bank codes 4c3x and 4c3y for Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD, respectively.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The pET15b-kstD1 plasmid (2) was used as the template for site-directed mutagenesis to introduce Y119F, Y318F, and Y487F point mutations into Δ1-KSTD1. Forward mutagenic primer sequences, which were designed using the QuikChange® primer design program, were 5′-gt gcg ttc ccc gac tTc tac aaa gcc gaa gg-3′ for Y119F, 5′-c ctc aac gag tcg ctt ccg tTc gac cag ttc g-3′ for Y318F, and 5′-tg agc ggc cgc ttc tTc ccc ggc c-3′ for Y487F. The mutated nucleotides are shown as capital letters. Reverse mutagenic primer sequences were complementary to the forward primers and had the same lengths. The mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange® II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the instruction manual. Following mutagenesis, the plasmid template was digested using DpnI, and each of the mutants was transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue supercompetent cells (Stratagene). Individual clones of these E. coli variants were grown, and their plasmids were isolated for sequencing and transformation into the expression strain E. coli BL21(DE3). All mutant proteins were expressed and purified using the same procedures as the wild-type protein. The mutants were expressed at roughly the same level and crystallized under the same conditions as the wild-type enzyme, implying that no large scale conformational or stability changes were caused by the mutations.

Steady-state Kinetics

The steady-state kinetics parameters of Δ1-KSTD1 and its mutants were determined by measuring the dehydrogenase activity of the enzyme on the substrate 4-AD (Sigma) using dichlorophenol indophenol (Sigma) as an artificial electron acceptor. The stock solution of the substrate was prepared in ethanol. Activity assays were carried out at room temperature using 1-ml samples that had a typical composition (final concentration) of 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, 60 μm dichlorophenol indophenol, 4-AD (varying concentrations), and protein (chosen concentration). For each protein variant, seven different substrate concentrations (each in triplicate) were used. The protein concentrations were chosen such that the amount of consumed substrate at the end of the measurement was less than 10%. Controls were prepared by omitting the substrate. Except for the enzyme, all sample components were preincubated for 3 min, and the reactions were initiated by adding the enzyme. The reduction of dichlorophenol indophenol was monitored by measuring the decrease of its absorbance at 605 nm using an Ultrospec 4300 Pro UV-visible spectrophotometer (Amersham Biosciences) every minute for 5 or 6 min, and the data were collected using the SWIFT II reaction kinetics software (Amersham Biosciences). The kinetics parameters were analyzed by nonlinear regression curve fitting of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression, Purification, and Preliminary Characterization

Δ1-KSTD1 was expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) from the pET15b-kstD1 plasmid (2). Therefore, in addition to the Δ1-KSTD1 amino acid sequence (510 residues), the expressed protein also contains a His-tagged 20-amino acid leader sequence (MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSH). The expressed protein was purified in three steps of, successively, immobilized Ni2+ affinity, anion exchange, and size exclusion chromatography (17). The purified protein was colored brightly yellow and exhibited a typical absorption spectrum for a flavoprotein with maxima at 275, 377, and 464 nm (data not shown). Moreover, a Pfam search (28) using the amino acid sequence of Δ1-KSTD1 revealed that the sequence could be assigned to Pfam family PF00890, which is a protein family that binds FAD. Taken together, the expressed Δ1-KSTD1 comprises 530-amino acid residues and one FAD molecule with a calculated molecular mass of 55,995 Da (17).

Crystal Structure Determination

The Δ1-KSTD1 holoenzyme and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD complex crystallized under the same conditions and had the same space group P212121 with similar unit cell parameters. The crystal structure of Δ1-KSTD1 was solved using multiwavelength anomalous dispersion data collected from a Pt-derivatized crystal (17), whereas that of Δ1-KSTD1·ADD was elucidated by rigid body fitting using the refined model of the holoenzyme and subsequent refinement. The structures were determined at 2.0 and 2.3 Å resolution for Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD, respectively, with R factor and Rfree (for 5% of the data not included in the refinement selected in thin shells) values as expected for their resolutions. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Summary of x-ray data collection and processing

The values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell. Ii(h) is the integrated intensity of a reflection, <I(h)> is the mean intensity of multiple corresponding symmetry-related reflections, and N is the multiplicity of the given reflections.

| Crystal | Δ1-KSTD1a | Δ1-KSTD1·ADD |

|---|---|---|

| Beam line | ID14-1 (ESRF) | ID14-1 (ESRF) |

| Detector | ADSC Q210 | ADSC Q210 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.93340 | 0.93340 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.00 (2.11–2.00) | 2.30 (2.42–2.30) |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell | ||

| a (Å) | 107.4 | 107.7 |

| b (Å) | 131.6 | 132.1 |

| c (Å) | 363.2 | 363.6 |

| α = β = γ (°) | 90 | 90 |

| Molecules per asymmetric unit | 8 | 8 |

| Matthew's coefficient (Å3 Da−1) | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Solvent content (%) | 57 | 57 |

| Rmergeb | 0.084 (0.752) | 0.126 (0.717) |

| Rp.i.m.c | 0.050 (0.450) | 0.066 (0.374) |

| Total observations | 1,296,759 (183,757) | 1,048,445 (145,885) |

| Unique reflections | 345,382 (49,404) | 229,728 (32,222) |

| Mean I/σI | 10.9 (1.8) | 7.2 (1.9) |

| Completeness | 99.8 (98.6) | 99.5 (96.7) |

| Multiplicity | 3.8 (3.7) | 4.6 (4.5) |

a Data collection statistics according to Rohman et al. (17).

b Rmerge = ΣhΣi|Ii(h) − <I(h)>|/ΣhΣiIi(h).

c Rp.i.m. = Σh[1/(N − 1)]½Σi|Ii(h) − <I(h)>|/ΣhΣiIi(h).

TABLE 2.

Refinement statistics

| Crystal | Δ1-KSTD1 | Δ1-KSTD1·ADD |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) | 49.3–2.0 | 49.4–2.3 |

| Number of reflections | 327,731 | 217,960 |

| R factor (%)a | 17.9 | 21.3 |

| Rfree (%)b | 20.8 | 24.8 |

| Number of atoms | ||

| Total | 33,549 | 31,708 |

| Protein | 29,620 | 29,620 |

| FAD | 424 | 424 |

| Na+ | 4 | 4 |

| Cl− | 8 | 0 |

| Tetraethylene glycol | 247 | 78 |

| Sucrose | 276 | 0 |

| ADD | 0 | 168 |

| Water | 2,970 | 1,414 |

| RMSDs | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.51 | 1.40 |

| Ramachandran statisticsc | ||

| In preferred regions (%) | 97.2 | 96.9 |

| In allowed regions (%) | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| In disallowed regions (%) | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Mean B values (Å2) | ||

| Overall | 32.9 | 41.3 |

| Protein | 32.0 | 41.6 |

| FAD | 24.7 | 33.2 |

| Na+ | 23.7 | 30.7 |

| Cl− | 31.9 | |

| Tetraethylene glycol | 67.4 | 64.2 |

| Sucrose | 52.0 | |

| ADD | 45.7 | |

| Water | 38.2 | 34.9 |

| Protein Data Bank code | 4c3x | 4c3y |

a R factor = Σhkl||FP(obs)| − |FP(calc)||/Σhkl|FP(obs)|, where |FP(obs)| and |FP(calc)| are observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

b Rfree is R factor for 5% of the data not included in the refinement selected in thin shells.

c Ramachandran statistics were obtained from COOT (26).

For each of the models reported here, there are eight Δ1-KSTD1 monomers (denoted as chains A–H in the Protein Data Bank files) in the crystallographic asymmetric unit. Except for the first 22 amino acid residues, including the 20-amino acid leader sequence and the first two residues of Δ1-KSTD1, all residues could be positioned in the electron density. However, for residues 421–423 of monomers B, C, F, and G, the electron densities are very weak, indicating conformational flexibility and/or disorder. A total of 2,970 and 1,414 water molecules could be modeled unequivocally and refined in the final model of Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD, respectively. The electron density showed the presence of an FAD molecule in each monomer. Based on its electron density and octahedral coordination geometry, a sodium ion was identified at the interface between two monomers on a 2-fold symmetry axis. In the Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ1-KSTD1·ADD electron density maps, clear densities were present for a chloride ion, which most likely originated from the protein storage buffer, and an ADD ligand, respectively, in each of the eight monomers.

Oligomeric Structure

Δ1-KSTD1 crystallizes with eight monomers in the asymmetric unit. These eight monomers form two independent, very similar tetramers (ABCD and EFGH), which have noncrystallographic 222 symmetry. Superposition of these tetramers gave an RMSD of 0.44 Å for 1,940 of 2,026 Cα atoms. A calculation of the buried solvent-accessible surface areas caused by intermonomer interactions in the ABCD tetramer resulted in values of 1,622, 633, 1,161, 517, 534, and 1,662 Å2 for the AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, and CD interactions, respectively. These values suggest that the tetramer is a dimer of dimers, i.e., AB and CD, instead of a homotetramer. A sodium ion was found in the AB dimer interface on the noncrystallographic 2-fold symmetry axis relating the A and B chains. Asp154, Gln155, and Gln160 from each chain ligate the sodium ion. A sodium ion is also present at the corresponding position in the CD interface.

Although many hydrogen bonding interactions exist between the monomers in the dimer and tetramer, size exclusion chromatography indicated that Δ1-KSTD1 occurs as monomers in solution. Moreover, most residues involved in hydrogen bonding interactions in the dimer interface are relatively variable among Δ1-KSTDs (data not shown). Thus, the intermolecular contacts observed in the Δ1-KSTD1 crystal structure are most likely biologically insignificant.

Overall Fold and Domains

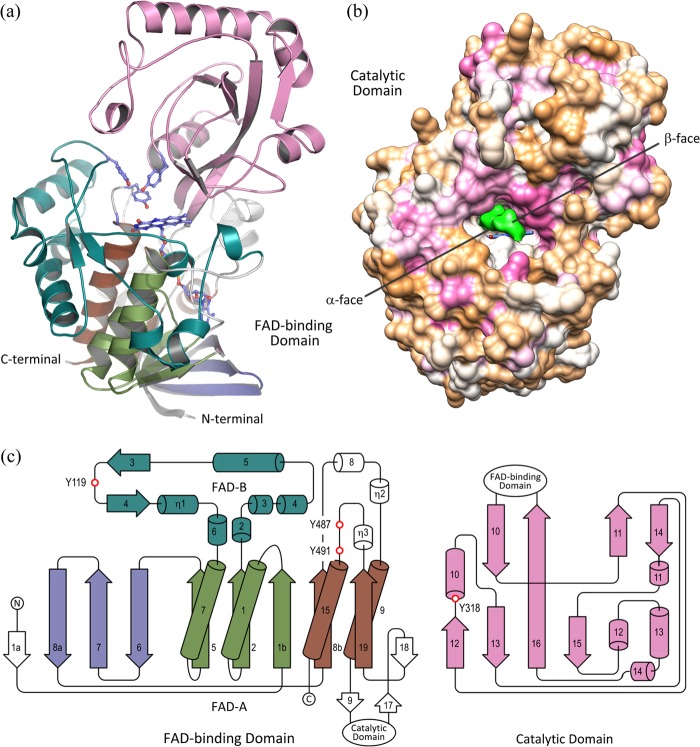

All Δ1-KSTD1 monomers exhibit a highly similar fold with an overall Cα RMSD of 0.18 Å when all amino acid residues are structurally aligned. Each Δ1-KSTD1 molecule has an elongated shape with dimensions of ∼40 × 45 × 70 Å3 and is organized in two domains: an FAD-binding domain and a catalytic domain (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure and topology diagram of Δ1-KSTD1. a, ribbon drawing of the Δ1-KSTD1 monomer. The catalytic domain (in pink) is at the top, whereas the FAD-binding domain is at the bottom. In the FAD-binding domain, the first half, the second half, and the β-meander crossover of the Rossmann fold (subdomain FAD-A) are colored pale green, brown, and deep blue, respectively, whereas subdomain FAD-B is in deep teal. The side chains of the three tyrosine residues in the active site, as well as FAD, are shown in ball and stick representation with carbon atoms in blue. b, molecular surface drawing of Δ1-KSTD1 colored according to its hydrophobicity (minimum, tan; zero, white; maximum, hot pink). The electron density for the bound ADD ligand is represented as a green surface with its faces indicated as α and β. FAD is depicted in ball and stick representation with carbon atoms in blue. The Δ1-KSTD1 molecule is in approximately the same orientation as in a. c, simplified secondary structure topology diagram of Δ1-KSTD1 colored in accordance with a. Cylinders and arrows symbolize helices and β-strands, respectively. Key residues for enzyme activity are indicated with red circles. Secondary structure elements were assigned using DSSP (37). Figs. 2a, 3a, and 4 were prepared with the program PyMOL (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 0.99, Schrödinger), whereas Fig. 2b was made with the program Chimera (38).

The FAD-binding domain consists of two separate polypeptide segments (residues 3–278 and 449–510) forming subdomains FAD-A and FAD-B. Subdomain FAD-A essentially folds into a central five-stranded parallel β-sheet sandwiched by a three-α-helix bundle at one side and a twisted three-stranded β-meander and an α-helix at the other side (Fig. 3a). The arrangement adopts the Rossmann fold, the well known mononucleotide-binding fold with a basic topology of a symmetrical α/β structure composed of two halves of β1-α1-β2-α2-β3 and β4-α4-β5-α5-β6 connected at the β3 and β4 strands by an α-helix (α3) crossover (29, 30). The first half of the Rossmann fold of Δ1-KSTD1 (β1b-α1-β2-α7-β5) is very similar to the basic topology, whereas the second half (β8b-α9-β19-α15) is slightly different because of a missing third β-strand. Moreover, instead of an α-helix, Δ1-KSTD1 uses a three-stranded β-meander as a crossover to connect the two halves of its Rossmann fold. Such a fold has been identified in the glutathione reductase structural family and can be observed in many different FAD-containing enzymes catalyzing a wide variety of reactions (29). In addition to the Rossmann fold, the FAD-A subdomain also includes several secondary structure elements inserted between β8b and α9, as well as β19 and α15. The FAD-B subdomain is inserted between β2 and α7, whereas the catalytic domain (residues 279–448), where the catalytic residue Tyr318 comes from, is in between α9 and β19 of the FAD-A subdomain.

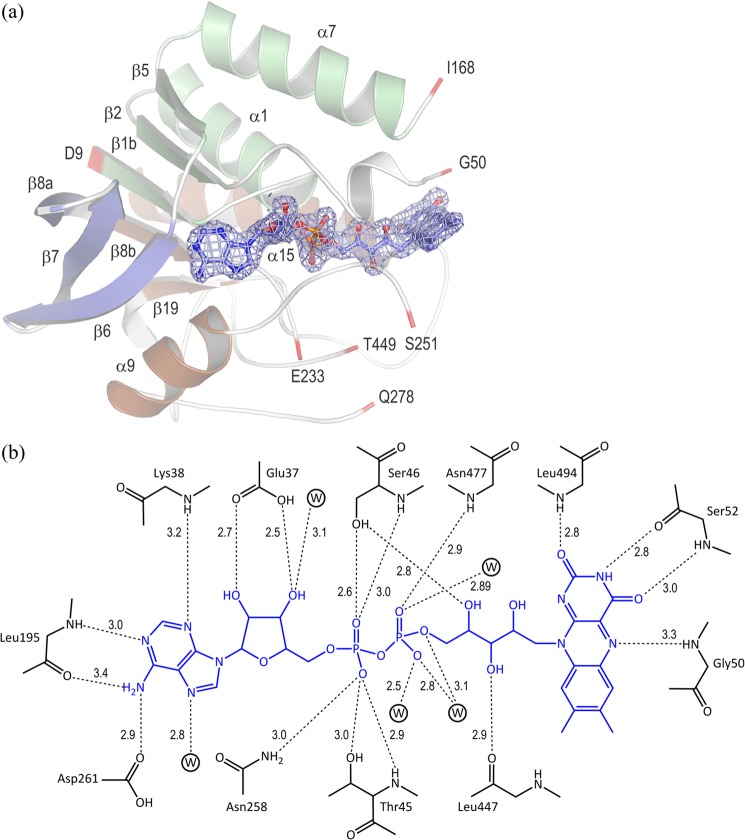

FIGURE 3.

The FAD-binding site of Δ1-KSTD1. a, ribbon drawing of the Rossmann fold (subdomain FAD-A) of Δ1-KSTD1 and its interaction with FAD. The color scheme is the same as that of Fig. 2a. Various interdomain/subdomain residues are numbered and colored in red. FAD is represented as balls and sticks with blue carbon atoms; its electron density is contoured at 1.8 σ. b, schematic drawing emphasizing the hydrogen bonds between FAD and protein and water (circled W) molecules. The hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines, and their distances, which were adopted from chain A of Δ1-KSTD1 structure, are indicated in Ångströms.

A structural similarity search using the DALI server (31) indicated that Δ1-KSTD1 is related to many FAD-binding proteins, with the highest similarity to 3-ketosteroid Δ4-(5α)-dehydrogenase (Δ4-(5α)-KSTD) from Rhodococcus jostii (Protein Data Bank entry 4at0; Z-score 39.4; RMSD 3.4 Å; 28% sequence identity) (32), followed by flavocytochrome c fumarate reductase from Shewanella putrefaciens (Protein Data Bank entry 1d4c; Z-score 37.2; RMSD 3.8 Å; 24% sequence identity) (33).

FAD-binding Site

Most of the FAD coenzyme is buried in an elongated cavity in the FAD-binding domain. It adopts an extended conformation comparable to those in other proteins of the glutathione reductase family (29). Its adenine end is tethered in front of the parallel β-sheet of the Rossmann fold, and its isoalloxazine ring is at the edge of the FAD-binding domain pointing to the catalytic domain. The isoalloxazine ring has an almost planar conformation. Its si-face interacts with the α3-α4 loop of the FAD-binding domain, its re-face faces the catalytic domain, whereas the O4, C4A, N5, and C5A atoms face the bulk solvent. In both structures, the FAD molecules are in the oxidized state, as suggested by the solution spectrum of the protein and the bright yellow color of the crystals. As observed in the majority of FAD-containing proteins of the glutathione reductase family (29), the FAD coenzyme in Δ1-KSTD1 is bound noncovalently. The different parts of the coenzyme bind to the apo-enzyme through a variety of interactions, including hydrogen bonds, van der Waals contacts, and dipole-dipole interactions (Fig. 3).

The adenine moiety is nested in a hydrophobic pocket formed primarily by the side chains of Val13, Leu36, Lys38, Val194, Leu195, Ala229, and Ala262. The N1, N3, N6, and N7 atoms of this moiety are hydrogen-bonded to the protein. As also observed in other members of the glutathione reductase family (29), Δ1-KSTD1 contains a consensus dinucleotide-binding motif (29) of the XhXhGXGXXGXXXhXXhX7hXhE(D) type (where X is any residue, and h is a hydrophobic residue), i.e., 10VLVVGSGGGALTGAYTAAAQGLTTIVLE37 (the conserved residues are in bold), in which the third conserved glycine is replaced by alanine (Ala19). These residues are part of the β1b-α1-β2 portion of the first half of the Rossmann fold. The conserved Glu37 at the end of the motif (and at the C-terminal end of β2) has a bidentate hydrogen bonding interaction of its carboxylate group with the diol O2 and O3 atoms of the ribose. The pyrophosphate group is located in a site surrounded by amino acid residues from the α2 and η3 helices and the β8-α8 and η2-α9 loops, close to the α1 helix. The positive end of the helix dipole of this latter α-helix is in a good position to favorably interact with the double negative charge of the pyrophosphate. Additionally, four of the pyrophosphate oxygen atoms of the pyrophosphate are hydrogen-bonded to the apo-enzyme or water molecules. Except for the O2′ hydroxyl group, all hydroxyls of the ribityl moiety make hydrogen bonds to the protein. Of the isoalloxazine ring, the dimethylbenzene ring is found in a hydrophobic environment between the side chains of Tyr48, Ser49, Leu153, Met252, Phe294, Ile354, and Leu447, whereas the N5 atom and the pyrimidine moiety interact through hydrogen bonds with the protein backbone. In addition, the hydroquinone and semiquinone forms of the pyrimidine moiety, which is situated just near the N terminus of the α15 helix, may be stabilized by their interaction with the positive end of the macro-dipole moment of this helix.

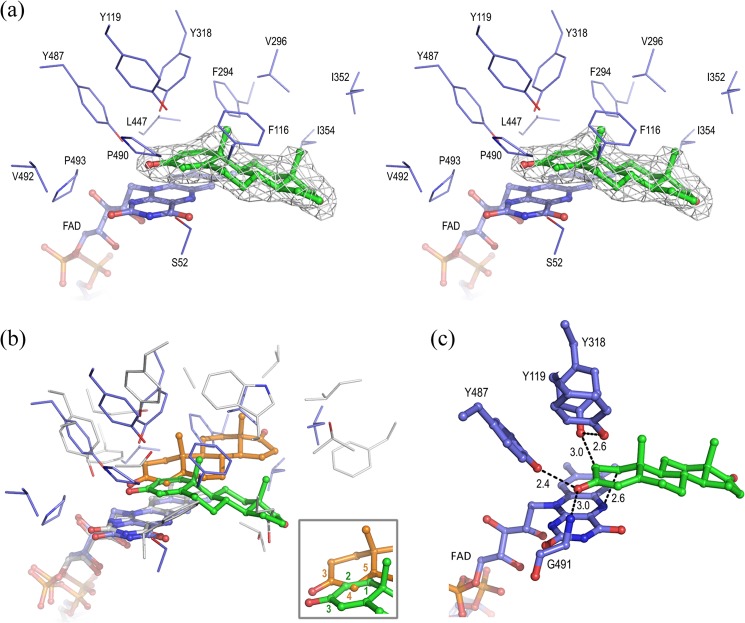

Active Site Structure

The electron density map of the Δ1-KSTD1·ADD complex revealed the presence of electron density in its active site compatible with a bound ADD molecule (Fig. 4a). The ADD is located at the interface between the FAD-binding and the catalytic domains, near the FAD-binding site. It is bound in a pocket-like cavity that is lined with hydrophobic amino acid residues originating from both domains and bordered by the re-face of the isoalloxazine ring of FAD (Figs. 2b and 4a). The apolar nature of the residues that line this pocket is conserved among Δ1-KSTD enzymes from different bacteria (data not shown). The electron density for the two axial β-methyl groups at the C10 and C13 atoms of ADD clearly defined the orientation of the 3-ketosteroid molecule. The A-ring of the 3-ketosteroid is nearly planar and lies almost parallel to the plane of the isoalloxazine ring. It is buried in the active site and sandwiched between the re-face of the pyrimidine moiety of the isoalloxazine ring system on its α-face and residues Tyr119 and Tyr318 on its β-face, whereas the five-membered D-ring of the 3-ketosteroid occupies a solvent-accessible pocket near the active site entrance.

FIGURE 4.

The active site of Δ1-KSTD1. a, wall-eyed stereo view of the active site of Δ1-KSTD1 with bound ADD product. ADD is depicted with green carbon atoms together with electron density contoured at 1.5 σ. FAD and the side chains of amino acid residues within 5.0 Å from the ADD are shown with blue carbon atoms. b, protein superposition based on the FAD molecules of Δ1-KSTD1·ADD and Δ4-(5α)-KSTD·4-AD. ADD is represented with green carbon atoms, whereas 4-AD is in orange. The FAD molecules and the amino acid residues within 5.0 Å from ADD and 4-AD are shown in blue and gray carbon atoms, respectively. Inset, a close-up view of the A-rings of the steroids in Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ4-(5α)-KSTD showing the superposition of the atoms between which the double bond is formed. c, 4-AD, a Δ1-KSTD1 substrate, modeled in the active site by superposition on the product. Hydrogen bonds and close contacts between substrate (green carbon atoms) and FAD and several active site residues (blue carbon atoms) are shown as dashed lines, and their distances are indicated in Ångströms. The superposition was performed with chain A of Δ1-KSTD1·ADD structure.

The ADD molecule is bound in the active site via a large number of van der Waals interactions (Fig. 4a). Phe116 is in a good position for hydrophobic stacking interactions with the B-ring of the 3-ketosteroid. The C3 carbonyl oxygen atom of the 3-ketosteroid forms hydrogen bonds with the Tyr487 hydroxyl group and the Gly491 backbone amide, whereas the C1 and C2 atoms are at short distances to the N5 atom of the isoalloxazine ring and the hydroxyl group of Tyr318, respectively. Binding of ADD does not induce significant conformational changes, as evidenced by the low RMSD of 0.27 Å for Cα atoms between the holoenzyme and enzyme-product complex structures.

The binding mode of ADD in the active site of Δ1-KSTD1 resembles that of 4-AD in Δ4-(5α)-KSTD, a flavoenzyme that introduces a 4,5-double bond into 3-keto-(5α)-steroids (32). However, a structural superposition of the proteins based on their FAD coenzymes revealed that the ADD and 4-AD ligands are bound in a similar orientation but rotated by ∼40° in the plane of the steroid ring system. Importantly, the C1, C2, and C3 carbonyl O atoms of ADD virtually superpose on the C5, C4, and C3 carbonyl O atoms of 4-AD, respectively (Fig. 4b). In addition, the hydroxyl groups of Tyr318 and Tyr487 of Δ1-KSTD1 are in very similar positions to those of Ser468 and Tyr466 of Δ4-(5α)-KSTD, respectively. Whereas in Δ4-(5α)-KSTD, the Ser468 hydroxyl group abstracts a proton from the C4 carbon atom of the substrate, and in Δ1-KSTD1, the Tyr318 hydroxyl group is in a position to abstract a proton from C2. Similarly, the N5 atom of FAD can accept a hydride ion from C5 (Δ4-(5α)-KSTD) or C1 (Δ1-KSTD1). Finally, Tyr487 of Δ1-KSTD1 can promote keto-enol tautomerization at C3 keto-group, similar to Tyr466 of Δ4-(5α)-KSTD. Therefore, this binding mode is in agreement with Δ1-KSTD1 abstracting a hydride ion and a proton from the C1 and C2 atoms of its 4-AD substrate, respectively, and the C3 carbonyl group of the substrate is involved in keto-enol tautomerization. Thus, whereas the nature of the catalytic residues is the same in Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ4-(5α)-KSTD, the substrate is bound in a different orientation, exposing either the C1-C2 bond (Δ1-KSTD1) or the C4-C5 bond (Δ4-(5α)-KSTD) to the catalytic residues. This different orientation fully explains the different regiospecificity of Δ1-KSTD1 and Δ4-(5α)-KSTD.

Active Site Residues and Mutational Studies

An amino acid sequence alignment of the available Δ1-KSTDs from different bacteria revealed that, among the amino acids lining the active site of Δ1-KSTD1, four residues are strictly conserved (data not shown). These residues are Tyr119, Tyr487, and Gly491 from the FAD-binding domain and Tyr318 from the catalytic domain. These four residues are spatially close to the bound ADD molecule. To assess their importance for Δ1-KSTD1 activity, the tyrosine residues were mutated into phenylalanines (Y119F, Y318F, and Y487F). All mutants were expressed, purified, and crystallized, employing the same protocol as used for the wild-type enzyme, and their enzymatic properties were compared.

The steady-state kinetic parameters of wild-type and mutant enzymes are shown in Table 3. A substantial reduction in dehydrogenase activity was observed for all three mutants, verifying their importance for activity of Δ1-KSTD1. The Y318F mutation had the largest effect; it completely abolished the dehydrogenase activity of the enzyme. As discussed above, the hydroxyl group of Tyr318 is situated close to the C2 atom of the bound ADD product, a position compatible with a role as catalytic base that abstracts a proton from the C2 atom of 4-AD. Surprisingly, the Y119F mutation also showed a drastic reduction of the dehydrogenase activity, with only ∼0.05% of the wild-type specific activity remaining. Tyr119 has no close contacts with the bound ADD in the Δ1-KSTD1·ADD complex structure, but its hydroxyl group is at hydrogen-bonding distance from the hydroxyl group of Tyr318 and thus may serve to increase the basic character of the catalytic base and facilitate proton relay. On the other hand, the Y487F mutation had only a relatively modest effect with a residual activity of ∼2.6% of that of the wild-type enzyme, despite the hydrogen bonding interaction of the hydroxyl group of Tyr487 with the C3 carbonyl oxygen of ADD. An explanation for this observation could be that the backbone amide of Gly491 has also a hydrogen bonding interaction with the C3 carbonyl oxygen. Apparently, these two active site residues may act in tandem, and therefore the absence of Tyr487 does not completely abolish the dehydrogenase activity of Δ1-KSTD1. Together they may promote keto-enol tautomerization and labilization of the C2 hydrogen atoms.

TABLE 3.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of wild-type Δ1-KSTD1 and its mutants

The dehydrogenase activity was measured using seven different 4-AD substrate concentrations ranging from 7.5 to 240, 60 to 1,000, and 40 to 700 μm for wild-type, Y119F, and Y487F enzyme, respectively. The enzyme concentrations were approximately 360 × 10−6 μm, 1.07 μm, and 18 × 10−3 μm for the wild-type, Y119F, and Y487F enzyme, respectively. The values are the averages of triplicate measurements.

| Variant | Specific activity | Activity | Km | kcat | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol·mg−1·min−1 | % | μm | s−1 | s−1·m−1 | |

| Wild-type | 72,900 ± 1,500 | 100 | 37.0 ± 0.8 | 68.1 ± 1.4 | 1,838,000 ± 67,000 |

| Y119F | 38.6 ± 2.5 | 0.05 | 335 ± 51 | 0.036 ± 0.002 | 108 ± 12 |

| Y318F | NMa | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| Y487F | 1,868 ± 53 | 2.6 | 193 ± 12 | 1.7 ± 0.05 | 9,061 ± 844 |

a NM, not measurable.

Catalytic Mechanism

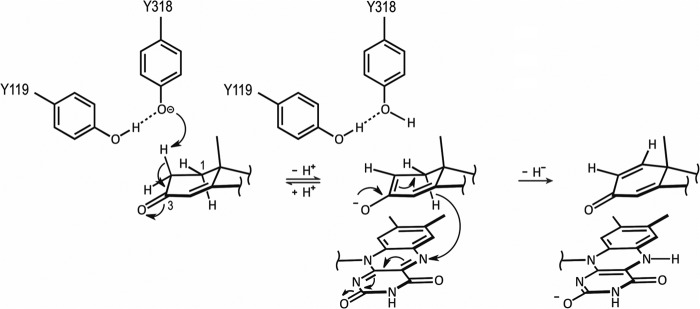

The catalytic cycle of a typical flavoenzyme includes two half-reactions, i.e., a reductive half-reaction and an oxidative half-reaction (34). In the reductive half-reaction, the flavin coenzyme is reduced by a substrate, whereas in the oxidative half-reaction, the reduced coenzyme is reoxidized by an electron acceptor (34). For Δ1-KSTDs, the physiological electron acceptor is not known, although vitamin K2(35) has been proposed as a natural cosubstrate for the enzyme (35, 36). In contrast, the reductive half-reaction has been intensively studied (1, 2). The enzyme is able to use a variety of 3-ketosteroid substrates, with a preference for those possessing a double bond at the C4-C5 position (1, 2). Based on our structural and mutational studies described above, a detailed catalytic mechanism of the reductive half-reaction can now be proposed (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Proposed dehydrogenation mechanism catalyzed by Δ1-KSTD1. The hydroxyl group of Tyr487 and the backbone amide of Gly491 (both not shown for clarity) bind the C3 keto-group of the substrate, promoting keto-enol tautomerization and labilization of the C2 hydrogen atoms. Tyr318, whose basic character is enhanced by a hydrogen bond with Tyr119, abstracts the axial β-hydrogen from the C2 atom as a proton. The ensuing enolate may undergo hydrogen exchange at the C2 atom with the solvent via Tyr318. Upon migration of the negative charge of the species to the C1 atom and transfer as a hydride ion of the axial α-hydrogen of the C1 atom to the N5 atom of the isoalloxazine ring of FAD, a double bond is formed between the C1 and C2 atoms.

A structural superposition of the substrate 4-AD on the product ADD as bound in the Δ1-KSTD1·ADD complex structure revealed that 1) the C1 atom of 4-AD would be at ∼2.6 Å from the N5 atom of the FAD isoalloxazine ring; 2) the C2 atom of 4-AD would be at ∼3.0 Å from the hydroxyl group of Tyr318; 3) the isoalloxazine ring and Tyr318 would be on opposite faces of the A-ring of the substrate, with the isoalloxazine ring at the α-face and Tyr318 at the β-face; and 4) the C3 carbonyl group of the substrate would be at hydrogen-bonding distance to the hydroxyl group of Tyr487 (2.4 Å) and the backbone amide of Gly491 (3.0 Å). Thus, the substrate would be bound in the active site such that its C1 and C2 atoms are positioned appropriately for hydride and proton abstraction, respectively (Fig. 4c).

The position of Tyr487 and Gly491 and their hydrogen bonding interactions with the C3 keto group of 4-AD suggest that they may function in promoting keto-enol tautomerization and labilization of the C2 hydrogen atoms. Whether during the reaction a proton is transferred from the Tyr487 hydroxyl group to the enolate oxygen atom is currently unknown, but given the significant residual activity of the Y487F mutant protein (Table 3), such a transfer appears not to be absolutely necessary. The Tyr318 hydroxyl group is at reaction distance to the axial β-hydrogen of the C2 atom (2β-hydrogen) and is in the right position to serve as a general base that abstracts the 2β-hydrogen. It has a hydrogen bonding interaction with the hydroxyl group of Tyr119, which may enhance the basic character of the Tyr318 hydroxyl group. Moreover, Tyr318 is positioned at the N-terminal end of α-helix α10, and the positive helix macro-dipole may provide additional stabilization to the (transient) phenolate form of Tyr318. How the abstracted proton is transferred to the solvent is less clear; Tyr119 may have a role in the proton relay, but the possible proton acceptors, a water molecule or the conserved Tyr414 hydroxyl group, are too far away (at 5 Å). However, breathing motions of the protein could reduce this distance or allow water to enter and accept the proton from Tyr119. Indeed, the electron density suggests that several residues in this region are flexible (e.g., Phe116).

As a result of proton abstraction by Tyr318, a transient carbanionic species is formed, which is most likely stabilized by keto-enol tautomerization. The negative charge of this species is then transferred to the C1 atom to form a double bond between the C1 and C2 atoms. In concert with this, the axial α-hydrogen of the C1 atom (1α-hydrogen), which is in close proximity to the re-face of the N5 of the isoalloxazine ring, is transferred as a hydride ion to the N5 atom, generating a semireduced anionic FAD. The negative charge of this anion is likely delocalized over the pyrimidine moiety of the isoalloxazine ring system, which is stabilized by hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl and amide backbone of Ser52 and the amide backbone of Leu494 as well as by the helix macro-dipole interaction with the N-terminal end of helix α15. Reoxidation of the FAD in the subsequent oxidative half-reaction will make the enzyme ready for another cycle of catalysis.

The above mechanism is in full agreement with the stereochemistry of the dehydrogenation reaction catalyzed by Δ1-KSTDs, which preferentially proceeds via a trans-diaxial elimination of the 1α and 2β-hydrogens (9–11). However, whereas the 1α-hydrogen release is an absolute requirement, the 2β-hydrogen loss is not obligatory (10). A dehydrogenation experiment with the Δ1-KSTD from Bacillus sphaericus using 2β-deuterio-5α-androstane-3,17-dione as substrate showed only 86% loss of the deuterium (10). Although reportedly the deuterated substrate was not the pure 2β-isomer (10), the incomplete loss of the 2β-hydrogen could also be due to the formation of a reactive transient species that may undergo fast hydrogen exchange at the C2 atom (9–11). Such a hydrogen exchange may decrease the stereoselectivity of 2β-hydrogen elimination. The reactive species was suggested to be either a keto-enolate (10, 11) or a carbanion (9). Both suggestions are based on the fact that Δ1-KSTD may catalyze hydrogen exchange at the C2 atom of its substrate, even when 1α-hydrogen expulsion was prevented by the absence of an electron acceptor for the oxidative half-reaction (10, 11) or by keeping the flavin coenzyme in the reduced state (9). Indeed, our structures and the observed binding mode of 4-AD show that the active site of the enzyme architecture can stabilize a transient keto-enolate during the reaction, supporting a catalytic mechanism that makes use of keto-enol tautomerization similar to the mechanism of Δ4-(5α)-KSTD (32).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Lubbert Dijkhuizen, Dr. Robert van der Geize, and Dr. Jan Knol (Department of Microbiology, University of Groningen) for providing the pET15b-kstD1 plasmid and initial Δ1-KSTD1 protein samples and for helpful discussions. We thank the beam-line scientists of ID14-1 (European Synchrotron Radiation Facility) for assistance.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4c3x and 4c3y) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- Δ1-KSTD

- 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase

- Δ1-KSTD1

- 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase isoenzyme 1 from R. erythropolis SQ1

- 4-AD

- 4-androstene-3,17-dione

- ADD

- 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- Δ4-(5α)-KSTD

- 3-ketosteroid Δ4-(5α)-dehydrogenase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Itagaki E., Wakabayashi T., Hatta T. (1990) Purification and characterization of 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase from Nocardia corallina. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1038, 60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knol J., Bodewits K., Hessels G. I., Dijkhuizen L., van der Geize R. (2008) 3-Keto-5α-steroid Δ1-dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 and its orthologue in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv are highly specific enzymes that function in cholesterol catabolism. Biochem. J. 410, 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Donova M. V. (2007) Transformation of steroids by actinobacteria. A review. Appl Biochem. Microbiol. 43, 1–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Horinouchi M., Hayashi T., Koshino H., Yamamoto T., Kudo T. (2003) Gene encoding the hydrolase for the product of the meta-cleavage reaction in testosterone degradation by Comamonas testosteroni. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 69, 2139–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Geize R., Hessels G. I., Dijkhuizen L. (2002) Molecular and functional characterization of the kstD2 gene of Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 encoding a second 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase isoenzyme. Microbiology 148, 3285–3292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wovcha M. G., Brooks K. E., Kominek L. A. (1979) Evidence for two steroid 1,2-dehydrogenase activities in Mycobacterium fortuitum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 574, 471–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayano M., Ringold H. J., Stefanovic V., Gut M., Dorfman R. I. (1961) The stereochemical course of enzymatic steroid 1,2-dehydrogenation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 4, 454–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levy H. R., Talalay P. (1959) Bacterial oxidation of steroids. II. Studies on the enzymatic mechanism of ring A dehydrogenation. J. Biol. Chem. 234, 2014–2021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Itagaki E., Matushita H., Hatta T. (1990) Steroid transhydrogenase activity of 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase from Nocardia corallina. J Biochem. 108, 122–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jerussi R., Ringold H. J. (1965) The mechanism of the bacterial C-1,2 dehydrogenation of steroids. III. Kinetics and isotope effects. Biochemistry 4, 2113–2126 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ringold H. J., Hayano M., Stefanovic V. (1963) Concerning the stereochemistry and mechanism of the bacterial C-1,2 dehydrogenation of steroids. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 1960–1965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghisla S., Thorpe C. (2004) Acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. A mechanistic overview. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 494–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thorpe C., Kim J. J. (1995) Structure and mechanism of action of the acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. FASEB J. 9, 718–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fujii C., Morii S., Kadode M., Sawamoto S., Iwami M., Itagaki E. (1999) Essential tyrosine residues in 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous. J. Biochem. 126, 662–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsushita H., Itagaki E. (1992) Essential histidine residue in 3-ketosteroid-Δ1-dehydrogenase. J. Biochem. 111, 594–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van der Geize R., Hessels G. I., van Gerwen R., van der Meijden P., Dijkhuizen L. (2001) Unmarked gene deletion mutagenesis of kstD, encoding 3-ketosteroid Delta1-dehydrogenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 using sacB as counter-selectable marker. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205, 197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rohman A., van Oosterwijk N., Dijkstra B. W. (2012) Purification, crystallization and preliminary x-ray crystallographic analysis of 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 68, 551–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Geize R., Grommen A. W., Hessels G. I., Jacobs A. A., Dijkhuizen L. (2011) The steroid catabolic pathway of the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi is important for pathogenesis and a target for vaccine development. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van der Geize R., Yam K., Heuser T., Wilbrink M. H., Hara H., Anderton M. C., Sim E., Dijkhuizen L., Davies J. E., Mohn W. W., Eltis L. D. (2007) A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1947–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pandey A. K., Sassetti C. M. (2008) Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4376–4380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brzezinska M., Szulc I., Brzostek A., Klink M., Kielbik M., Sulowska Z., Pawelczyk J., Dziadek J. (2013) The role of 3-ketosteroid 1(2)-dehydrogenase in the pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 13, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of COOT. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Read R. J. (1986) Improved Fourier coefficients for maps using phases from partial structures with errors. Acta Crystallogr. A 42, 140–149 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., Pang N., Forslund K., Ceric G., Clements J., Heger A., Holm L., Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Bateman A., Finn R. D. (2012) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290–D301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dym O., Eisenberg D. (2001) Sequence-structure analysis of FAD-containing proteins. Protein Sci. 10, 1712–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rossmann M. G., Moras D., Olsen K. W. (1974) Chemical and biological evolution of nucleotide-binding protein. Nature 250, 194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server. Conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Oosterwijk N., Knol J., Dijkhuizen L., van der Geize R., Dijkstra B. W. (2012) Structure and catalytic mechanism of 3-ketosteroid-Δ4-(5α)-dehydrogenase (Δ4-(5α)-KSTD) from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30975–30983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leys D., Tsapin A. S., Nealson K. H., Meyer T. E., Cusanovich M. A., Van Beeumen J. J. (1999) Structure and mechanism of the flavocytochrome c fumarate reductase of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1113–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghisla S., Massey V. (1989) Mechanisms of flavoprotein-catalyzed reactions. Eur J Biochem. 181, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abul-Hajj Y. J. (1978) Isolation of vitamin K2(35) from Nocardia restrictus and Corynebacterium simplex. A natural electron acceptor in microbial steroid ring A dehydrogenations. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 2356–2360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gale P. H., Page A. C., Jr., Stoudt T. H., Folkers K. (1962) Identification of vitamin K2(35), an apparent cofactor of a steroidal 1-dehydrogenase of Bacillus sphaericus. Biochemistry 1, 788–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kabsch W., Sander C. (1983) Dictionary of protein secondary structure. Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera. A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]