Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

In the largest head-to-head comparison between an oral and an intravenous (IV) iron compound in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) so far, we strived to determine whether IV iron isomaltoside 1,000 is non-inferior to oral iron sulfate in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia (IDA).

METHODS:

This prospective, randomized, comparative, open-label, non-inferiority study was conducted at 36 sites in Europe and India. Patients with known intolerance to oral iron were excluded. A total of 338 IBD patients in clinical remission or with mild disease, a hemoglobin (Hb) <12 g/dl, and a transferrin saturation (TSAT) <20% were randomized 2:1 to receive either IV iron isomaltoside 1,000 according to the Ganzoni formula (225 patients) or oral iron sulfate 200 mg daily (equivalent to 200 mg elemental iron; 113 patients). An interactive web response system method was used to randomize the eligible patient to the treatment groups. The primary end point was change in Hb from baseline to week 8. Iron isomaltoside 1,000 and iron sulfate was compared by a non-inferiority assessment with a margin of −0.5 g/dl. The secondary end points, which tested for superiority, included change in Hb from baseline to weeks 2 and 4, change in s-ferritin, and TSAT to week 8, number of patients who discontinued study because of lack of response or intolerance of investigational drugs, change in total quality of life (QoL) score to weeks 4 and 8, and safety. Exploratory analyses included a responder analysis (proportion of patients with an increase in Hb ≥2 g/dl after 8 weeks), the effect of regional differences and total iron dose level, and other potential predictors of the treatment response.

RESULTS:

Non-inferiority in change of Hb to week 8 could not be demonstrated. There was a trend for oral iron sulfate being more effective in increasing Hb than iron isomaltoside 1,000. The estimated treatment effect was −0.37 (95% confidence interval (CI): −0.80, 0.06) with P=0.09 in the full analysis set (N=327) and −0.45 (95% CI: −0.88, −0.03) with P=0.04 in the per protocol analysis set (N=299). In patients treated with IV iron isomaltoside 1,000, the mean change in s-ferritin concentration was higher with an estimated treatment effect of 48.7 (95% CI: 18.6, 78.8) with P=0.002, whereas the mean change in TSAT was lower with an estimated treatment effect of −4.4 (95% CI: −7.4, −1.4) with P=0.005, compared with patients treated with oral iron. No differences in changes of QoL were observed. The safety profile was similar between the groups. The proportion of responders with Hb ≥2 g/dl (IV group: 67% oral group: 61%) were comparable between the groups (P=0.32). Iron isomaltoside 1,000 was more efficacious with higher cumulative doses of >1,000 mg IV. Significant predictors of Hb response to IV iron treatment were baseline Hb and C-reactive protein (CRP).

CONCLUSIONS:

We could not demonstrate non-inferiority of IV iron isomaltoside 1,000 compared with oral iron in this study. Based on the dose–response relationship observed with the IV iron compound, we suggest that the true iron demand of IV iron was underestimated by the Ganzoni formula in our study. Alternative calculations including Hb and CRP should be explored to gauge iron stores in patients with IBD.

INTRODUCTION

Anemia is a frequent complication often seen in conjunction with acute exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) with known negative impact on quality of life (QoL) (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). The prevalence of anemia has been reported to be 6–74% in IBD (11). Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and anemia of chronic diseases are the most common causes of anemia in IBD. IDA is primarily caused by chronic blood loss, impaired gastrointestinal iron absorption, and upregulation of hepcidin due to inflammation, which inhibits enterocytic iron transport.

Control of the underlying inflammation and appropriate iron replacement therapy are therefore important in IBD. Although oral iron supplementation has traditionally been the treatment for IDA, intolerance often limits its use in IBD patients (12). An international guideline for management of anemia associated with IBD recommends intravenous (IV) administration of iron in patients with IBD (13), and some clinical studies support IV over oral iron supplementation (14,15,16). However, overall results are ambivalent because of studies in which no clear benefit in efficacy for IV over oral iron could be shown (8,17).

The aim of this study was to explore efficacy and safety of different modes of administration of iron isomaltoside 1,000 (Monofer, Pharmacosmos A/S, Holbaek, Denmark) compared with oral iron sulfate for treatment of IDA in IBD patients. The primary objective was to demonstrate that IV iron isomaltoside 1,000 is non-inferior to oral iron sulfate in treatment of IDA secondary to IBD, evaluated as the ability to increase hemoglobin (Hb). A non-inferiority study design was chosen based on the existing literature that both iron treatments could be equally efficacious, whereas they divagate regarding dosing limitation, administration (duration and frequency), and safety and tolerability profile. A non-inferiority margin of −0.5 g/dl was regarded as clinically relevant. The secondary objectives were to assess other relevant hematology and biochemical parameters, the effect on QoL, and safety. As part of safety, the effect of iron isomaltoside 1,000 on s-phosphate was measured as some IV iron therapies have been found to be associated with hypophosphatemia (18,19,20,21,22,23,24). Furthermore, exploratory analyses were performed in order to investigate the effect of regional differences and total iron dose level, and other potential predictors of the treatment response.

METHODS

Study design

This prospective, randomized, comparative, open-label, non-inferiority study was conducted in Austria, UK, Denmark, Hungary, and India from December 2009 to July 2012. The study protocol was approved by local ethics committees and competent authorities. The dates of the study was approved by the ethic committees are included in Supplementary Table 1 online. The study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

There were no important changes to methods after the study commenced.

Participants

The study took place at 36 sites (hospitals or private IBD clinics): 4 sites in Austria, 1 site in United Kingdom, 5 sites each in Denmark and Hungary, and 21 sites in India.

Patients ≥18 years of age with a diagnosis of IBD and a score of ≤5 on the Harvey–Bradshaw index for Crohn's disease (25) or a partial Mayo score of ≤6 for ulcerative colitis (26), a Hb <12 g/dl (7.45 mmol/l), and a transferrin saturation (TSAT) <20% were considered eligible to participate and if willing to provide written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were intolerance to oral iron treatment, other primary causes of anemia, hemochromatosis, hemosiderosis, hypersensitivity to IV iron complexes or iron sulfate, a history of multiple allergies, active intestinal tuberculosis/amoebic infections, liver cirrhosis, active hepatitis, acute infections, rheumatoid arthritis along with symptoms or signs of active joint inflammation, untreated vitamin B12/folate deficiency, pregnant or nursing women, and patients with extensive active bleeding necessitating blood transfusion or with planned elective surgery during the study. If the patient had participated in any other clinical study within 3 months, had taken any other IV or oral iron treatment within 4 weeks, had received blood transfusion within 4 weeks or erythropoietin within 8 weeks before screening or had any other medical condition that in the opinion of investigator may have caused the patient to be unsuitable for completion of the study or placed the patient at potential risk from being in the study, they were also excluded from participation in the study.

During the study, the patients were prohibited from having a blood transfusion, erythropoiesis stimulating agent treatment, and any iron supplementation other than investigational drugs as they would influence the outcome measures of the study. Furthermore, tetracycline, antacids, and cholestyramine were not allowed because of absorption interactions. IBD-related concomitant medication was allowed and did not necessarily need to be kept stable. All the blood samples were analyzed at two central laboratories in Europe and India. Cross-validation of laboratory values between laboratories was documented. C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured as a continuous parameter in Europe but as a positive/negative parameter in India. To be able to compare CRP across regions, CRP from European patients were evaluated as positive if >0.5 mg/dl.

Interventions

The total calculated IV iron requirement and administered cumulative dose in each patient in group A was calculated according to an adapted Ganzoni formula: cumulative iron dose (mg)=(body weight (kg)×(target Hb−actual Hb (g/dl)×2.4.+depot iron (set at 500 mg) where the target Hb was 13 g/dl (8.1 mmol/l), compared with the suggested 15 g/dl (9.3 mmol/l) in the original formula (27). Patients in treatment group A were randomized to either (A1) single once weekly infusion of up to 1,000 mg iron isomaltoside 1,000 (Monofer) over 15 min until reaching cumulative dosage or to (A2) single once weekly 500 mg bolus injections of iron isomaltoside 1,000 over 2 min until reaching cumulative dosage. All patients in group B received 200 mg oral iron sulfate (Ferro Duretter, manufactured by AstraZeneca, London, UK for the first batch and by GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK for the second batch; equivalent to 200 mg elemental iron) daily for 8 weeks. The dosing of Ferro Duretter was according to the product insert (28).

Outcomes

The patients attended seven visits during the 8-week study period. The assessments performed at each visit are shown in Supplementary Figure 1 online.

The primary end point was to assess the change in Hb from baseline to week 8. The secondary end points included change in Hb concentration from baseline to weeks 2 and 4, change in concentrations of s-ferritin and TSAT from baseline to week 8, number of patients who discontinued study because of lack of response or intolerance of investigational drugs, change in total QoL score from baseline to weeks 4 and 8 as measured by the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (29), and safety (adverse events (AEs), vital signs, electrocardiogram, s-phosphate, and other safety hematology and biochemistry parameters).

Exploratory analyses included number of patients, who responded with an increase in Hb ≥2 g/dl within 8 weeks, assessment of regional differences between Europe and India, influence on different cumulative doses of iron isomaltoside 1,000 (<1,000 mg,=1,000 mg, and >1,000 mg), and different biochemical makers and baseline characteristics on the Hb response.

The primary outcome was tested for non-inferiority whereas the remaining outcomes were tested for superiority. The outcomes are similar to other studies measuring treatment effect of iron treatment (30).

There were no changes to outcomes after the study commenced.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on absolute change in Hb from baseline to week 8. The non-inferiority margin was set as −0.5 g/dl. A two-sided significance level of 5% was used and the power was set to 80% and s.d. in change in Hb was assumed to be 1.5 g/dl. Based on these assumptions, a total of 321 patients were to be included in the efficacy analyses (i.e., provided post-randomization Hb measurements).

No interim analysis of efficacy parameters was performed, but s-phosphate as part of safety laboratory were analyzed after 25, 50, and 100 patients had been exposed to iron isomaltoside 1,000. The interim analysis was not related to the non-inferiority hypothesis, but purely part of monitoring safety in the study.

Randomization

Permuted block randomization was used to assign patients in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive either treatment A1 (weekly infusion of up to 1,000 mg iron isomaltoside 1,000 until reaching cumulative dosage), A2 (weekly 500 mg bolus injections of iron isomaltoside 1,000 until reaching cumulative dosage), or B (200 mg oral iron sulfate daily for 8 weeks). The block size was 6.

The randomization list was prepared centrally by a Contract Research Organization, Max Neeman International Data Management Centre, using a validated computer program (Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) PROC PLAN procedure). The randomization was stratified by whether the patient had received IV iron treatment in the past or not.

An interactive web response system method was used to randomize the eligible patient to the treatment groups. When the patient data had been entered into the interactive web response system, a unique randomization number was generated for the patient, identifying which treatment the patient was allocated to. The screening and enrollment of the patients were performed by the investigator at the site, whereas the entering of the patient data into the interactive web response system generating the randomization number was typically performed by the study nurse or study coordinator.

In line with previous studies, the study was not blinded since it is almost impossible to blind for oral iron as it is indicated by black stools. Furthermore, the primary end point is a biochemical measurement which unlikely is affected by the open-label study design.

Statistical methods

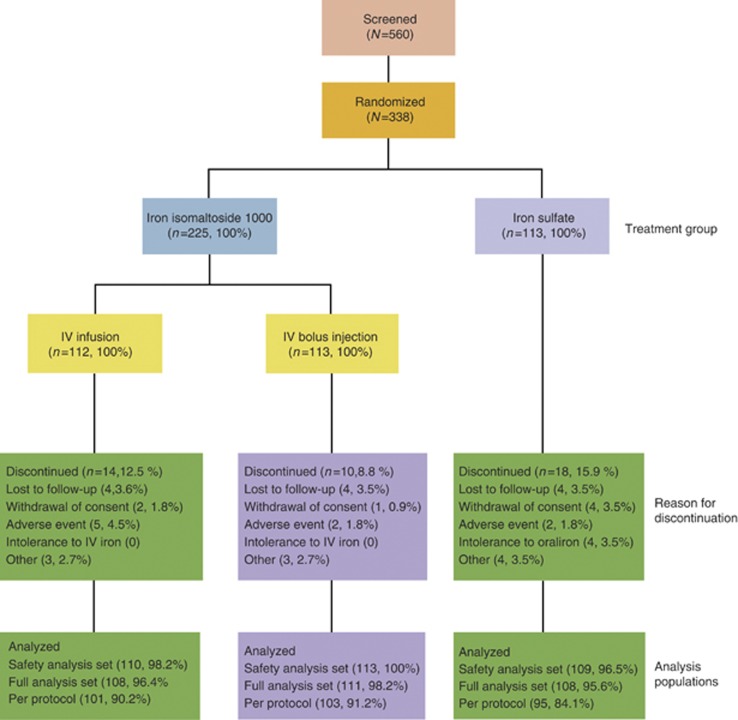

The following data sets were used in the analyses (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. IV, intravenous.

Safety analysis set (N=332): the safety population included all patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of the study drug.

Full analysis set (FAS; N=327): the FAS consisted of all the patients who were randomized into the study, received at least one dose of the study drug, and had at least one after baseline Hb assessment. The patients were included as randomized, regardless of which treatment they actually received.

Per protocol (PP) (N=299): the PP analysis set consisted of all the patients in the FAS who did not have any major protocol deviation.

The primary analysis was conducted on the FAS and PP analysis set. The secondary analyses of laboratory data were conducted on the FAS, whereas changes in QoL and safety analyses were conducted on the safety analysis set. The exploratory analyses were conducted on the FAS.

The primary end point was analyzed by a mixed model with repeated measures with treatment, visit, country, and stratum (IV iron Y/N) as factors, and baseline Hb as covariate. From the same model, treatment estimates and differences were deducted for weeks 2 and 4. A similar model was used to analyze other laboratory parameters, QoL, and potential predictors on Hb response (regional difference, cumulative dose, and other biochemical and baseline markers).

Response (increase in Hb ≥2 g/dl within 8 weeks) was analyzed by a logistic regression with treatment and selected baseline variables included in the model as factors or covariates. Also, an analysis with a separate model only including Hb was performed. In addition, the proportion of patients, who had a change in Hb ≥2 g/dl at any time from baseline to week 8, was compared between treatment groups by Fisher's exact test. Time to response was displayed by a Kaplan–Meier plot.

Baseline characteristics and safety data are displayed descriptively.

All tests were two-sided and the significance level was 0.05.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 560 patients were screened in the period 2 December 2009 to 30 May 2012 of whom 338 were randomized into two treatment groups: (A) iron isomaltoside 1,000 (225 patients) and (B) iron sulfate (113 patients). Treatment group A subsumed subgroup A1 (112 patients) and A2 (113 patients). The last patient's last visit was on the 30 July 2012.

Overall, patient discontinuation was comparable in both treatment groups (24/225 (11%) in group A and 18/113 (16%) in group B). Details of patient disposition are summarized in Figure 1. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall more women (63%) than men (37%) were included and a history of ulcerative colitis (69%) was more common than of Crohn's disease (31%). Baseline Hb was comparable between groups A and B. Regarding regional differences of the patient cohort, subjects from India were found to have more often a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis and a shorter duration of IBD. They were more frequently CRP negative, more severely anemic at baseline, and naive to IV iron ( Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and baseline characteristics.

|

Total |

Europe |

India |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Iron isomaltoside 1,000 (group A) | Oral iron (group B) | Total | Iron isomaltoside 1,000 (group A) | Oral iron (group B) | Total | Iron isomaltoside 1,000 (group A) | Oral iron (group B) | |

| Full analysis set | 327 | 219 | 108 | 130 | 87 | 43 | 197 | 132 | 65 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| Median | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 37 | 31 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Women | 206 (63%) | 139 (63%) | 67 (62%) | 98 (75%) | 65 (75%) | 33 (77%) | 108 (55%) | 74 (56%) | 34 (52%) |

| Men | 121 (37%) | 80 (37%) | 41 (38%) | 32 (25%) | 22 (25%) | 10 (23%) | 89 (45%) | 58 (44%) | 31 (48%) |

| Weight (kg) | |||||||||

| Median | 56 | 56 | 57 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| Race | |||||||||

| Asian | 200 (61%) | 134 (61%) | 66 (61%) | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 197 (100%) | 132 (100%) | 65 (100%) |

| Black | 2 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | — | — | — |

| Other | 2 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | — | — | — |

| White | 123 (38%) | 83 (38%) | 40 (37%) | 123 (95%) | 83 (95%) | 40 (93%) | — | — | — |

| Disease type | |||||||||

| Crohn's disease | 103 (31%) | 66 (30%) | 37 (34%) | 90 (69%) | 59 (68%) | 31 (72%) | 13 (7%) | 7 (5%) | 6 (9%) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 224 (69%) | 153 (70%) | 71 (66%) | 40 (31%) | 28 (32%) | 12 (28%) | 184 (93%) | 125 (95%) | 59 (91%) |

| Disease duration (years) | |||||||||

| Median | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Mayo score | |||||||||

| Median | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1.5 | 1 | 2.5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Harvey–Bradshaw index | |||||||||

| Median | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Previous oral iron | |||||||||

| No | 229 (70%) | 150 (68%) | 79 (73%) | 46 (35%) | 30 (34%) | 16 (37%) | 183 (93%) | 120 (91%) | 63 (97%) |

| Yes | 98 (30%) | 69 (32%) | 29 (27%) | 84 (65%) | 57 (66%) | 27 (63%) | 14 (7%) | 12 (9%) | 2 (3%) |

| Previous IV iron | |||||||||

| No | 273 (83%) | 184 (84%) | 89 (82%) | 82 (63%) | 56 (64%) | 26 (60%) | 191 (97%) | 128 (97%) | 63 (97%) |

| Yes | 54 (17%) | 35 (16%) | 19 (18%) | 48 (37%) | 31 (36%) | 17 (40%) | 6 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) |

| Concomitant mesalazinea | |||||||||

| No | 33 (27%) | 26 (31%) | 7 (18%) | 29 (59%) | 22 (65%) | 7 (47%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (8%) | — |

| Yes | 90 (73%) | 57 (69%) | 33 (83%) | 20 (41%) | 12 (35%) | 8 (53%) | 70 (95%) | 45 (92%) | 25 (100%) |

| Concomitant prednisolonea | |||||||||

| No | 89 (72%) | 57 (69%) | 32 (80%) | 28 (57%) | 17 (50%) | 11 (73%) | 61 (82%) | 40 (82%) | 21 (84%) |

| Yes | 34 (28%) | 26 (31%) | 8 (20%) | 21 (43%) | 17 (50%) | 4 (27%) | 13 (18%) | 9 (18%) | 4 (16%) |

| Concomitant azathioprinea | |||||||||

| No | 89 (72%) | 58 (70%) | 31 (78%) | 26 (53%) | 18 (53%) | 8 (53%) | 63 (85%) | 40 (82%) | 23 (92%) |

| Yes | 34 (28%) | 25 (30%) | 9 (23%) | 23 (47%) | 16 (47%) | 7 (47%) | 11 (15%) | 9 (18%) | 2 (8%) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | |||||||||

| Median | 9.9 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.6 |

| C-reactive protein | |||||||||

| Negative | 237 (72%) | 160 (73%) | 77 (71%) | 82 (63%) | 58 (67%) | 24 (56%) | 155 (79%) | 102 (77%) | 53 (82%) |

| Positive | 90 (28%) | 59 (27%) | 31 (29%) | 48 (37%) | 29 (33%) | 19 (44%) | 42 (21%) | 30 (23%) | 12 (18%) |

| s-ferritin (μg/l) | |||||||||

| Median | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 7.9 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | |||||||||

| Median | 5 | 5.1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 4 |

IV, intravenous.

Concomitant medication: mesalazine, prednisolone, or azathioprine taken before/during the study.

Exposure to iron

A total of 130 infusions of iron isomaltoside 1,000 were administered to the patients in subgroup A1 and 227 bolus injections were administered to the patients in subgroup A2. In addition, the safety analysis set included three patients, for whom no dose was recorded. The mean cumulative dose of iron isomaltoside 1,000 in the infusion and the bolus groups were 885 mg (s.d.: 238 mg, range: 195–1,500 mg) and 883 mg (s.d.: 296 mg, range: 350–2,500 mg), respectively, in the safety analysis set. There was no statistically significant regional difference in the mean IV dose. A cumulative dose of <1,000 mg was administered in 58%, whereas 42% received ≥1,000 mg iron. Oral iron was administered as 200 mg iron sulfate once daily for 8 weeks (11,200 mg elemental iron in total).

Efficacy results

Increase in Hb concentration

The primary analysis was conducted on the FAS (N=327) and PP analysis set (N=299).

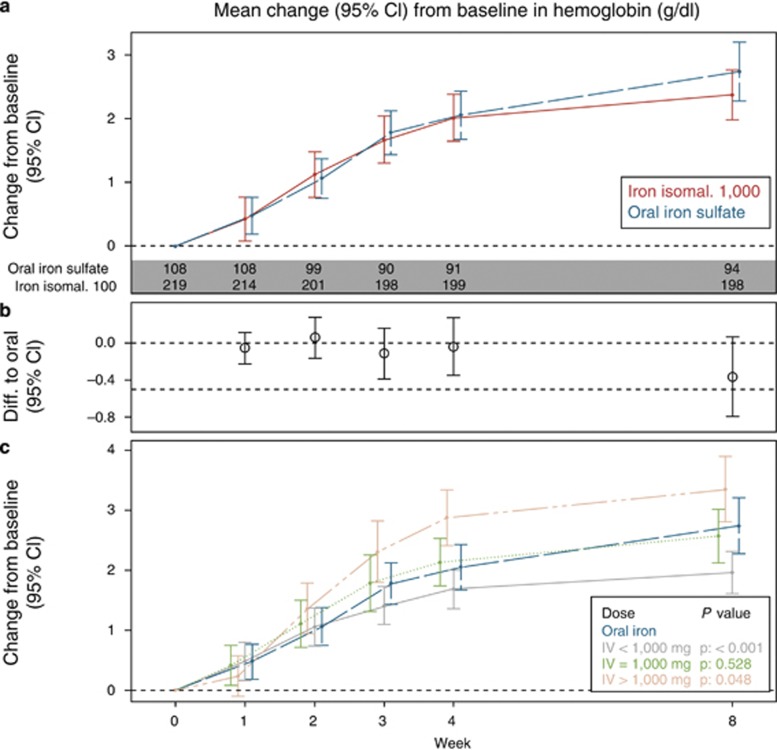

Non-inferiority could not be demonstrated on the primary end point. In the FAS, the mean (s.d.) Hb concentration in group A at baseline was 9.64 (1.65) g/dl, which increased to 12.23 (1.33) g/dl at week 8, whereas in group B, the Hb concentration increased from 9.61 (1.82) g/dl at baseline to 12.59 (1.91) g/dl at week 8 (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained in the PP analysis set (group A: 9.68 (1.67) g/dl increased to 12.28 (1.31) g/dl; group B: 9.69 (1.81) g/dl increased to 12.72 (1.77) g/dl) (Supplementary Figure 2). The mean change in Hb concentration from baseline to week 8 between groups A and B was statistically significantly different in the PP analysis set, but not in the FAS. The estimated treatment effect (A and B) was −0.37 (95% confidence interval (CI): −0.80, 0.06) with P=0.09 in the FAS and −0.45 (95% CI: −0.88, −0.03) with P=0.04 in the PP analysis set. Thus overall, a trend was observed for oral iron sulfate being more effective in increasing Hb than iron isomaltoside 1,000 with a statistical significant difference in the PP analysis set.

Figure 2.

Mean (95% CI) change from baseline in Hb by treatment and by dose, FAS. (a) Mean (95% CI) change from baseline between iron isomaltoside 1,000 and oral iron, (b) estimated difference (95% CI) between iron isomaltoside 1,000 and oral iron of change in Hb from baseline to each time-point. (c) Mean (95 % CI) change from baseline between iron isomaltoside 1,000 by dose (<1,000 mg, 1,000 mg, and >1,000 mg) and oral iron. Estimates (mean and 95% CI) from a mixed model with repeated measures with strata and country as factors, treatment*week interaction, and baseline value as covariate. P values refer to comparison to oral iron week 8. CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; Hb, hemoglobin; IV, intravenous.

The secondary analyses on Hb were conducted on the FAS (N=327). The mean change in Hb concentration from baseline to weeks 2 and 4 was not statistically significant between groups A and B. The estimated treatment effect (A and B) was 0.06 (95% CI: −0.16, 0.28) with P=0.6 at week 2 and −0.04 (95% CI: −0.35, 0.27) with P=0.8 at week 4.

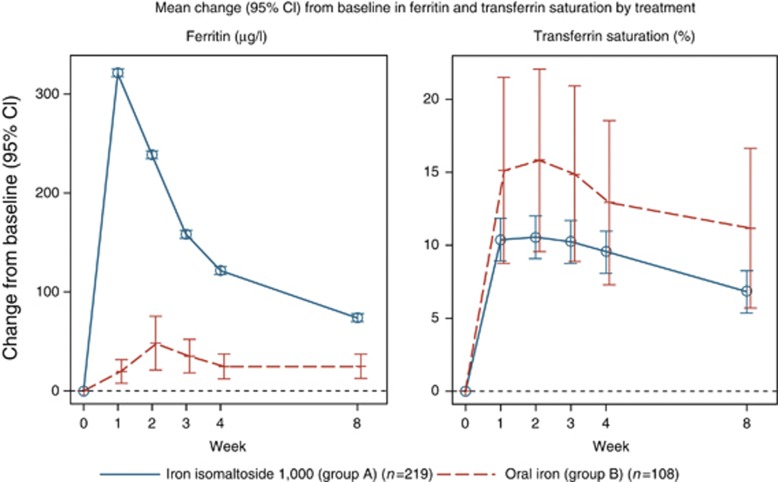

S-ferritin and TSAT

The analyses of change in s-ferritin and TSAT from baseline to week 8 were performed on the FAS (N=327).

The mean (s.d.) s-ferritin concentration in group A increased from baseline 32.8. (90.8) μg/l to 110.2 (231.4) μg/l at week 8 significantly higher than in group B (18.3 (36.0) μg/l at baseline to 54.1 (38.8) μg/l at week 8). The estimated treatment effect (A and B) was 48.7 (95% CI: 18.6, 78.8) with P=0.002 (Figure 3). The opposite was observed for the change in mean (s.d.) TSAT, which in group A rose from baseline was 8.2 (9.7) % to 17.4 (11.0) % at week 8, whereas in group B from 6.2 (4.4) % at baseline to 21.8 (13.2) % at week 8. The estimated treatment effect (A and B) was −4.4 (95% CI: −7.4, −1.4) with P=0.005 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean (95% confidence interval (CI)) change from baseline in s-ferritin and transferrin saturation by treatment. Estimates from a mixed model with repeated measures with strata and country as factors, treatment×week interaction, and baseline value as covariate.

QoL score

The analysis of QoL was performed on the safety analysis set (N=332).

There was an increase in the total QoL score from a median baseline score of 175 and 170 in groups A and B, respectively, to 189 in group A and 188 in group B at week 4 and to 195 in group A and 197 in group B at week 8, indicating an improvement in QoL. The increase was not statistically significant between the groups. The estimated treatment effect (A and B) was 1.92 (95% CI: −3.6, 7.5) with P=0.49 at week 4 and −3.72 (95% CI: −10.7, 3.2) with P=0.29 at week 8.

Exploratory analyses

A subanalysis was performed comparing treatment group A1 vs. A2 on the primary end point. In the FAS, the mean (s.d.) Hb concentration in group A1 at baseline was 9.74 (1.74) g/dl, which increased to 12.19 (1.41) g/dl at week 8, whereas in group A1, the Hb concentration increased from 9.54 (1.57) g/dl at baseline to 12.27 (1.25) g/dl at week 8. The change in Hb was not statistical different between group A1 and A2 (P=0.25). Exploratory analyses were further performed on the FAS (N=327) in order to investigate the effects of different IV dosages. A dose–response relative to the primary end point, change in Hb from baseline to week 8, was found within group A, where iron isomaltoside 1,000 was more efficacious with higher cumulative doses of >1,000 mg (Figure 2).

The difference in effect of IV vs. oral iron on change from baseline to week 8 in Hb was more pronounced in Indians, which was in contrast to Europeans, where the treatment effect of IV and oral iron was similar (Supplementary Figure 3). The estimated treatment effect (A and B) was −0.53 (95% CI: −0.13, 0.06) with P=0.08 at week 8 in Indians and 0.02 (95% CI: −0.52, 0.57) with P=0.9 at week 8 in Europeans.

Further analysis was performed on the responder criteria (Hb ≥2 g/dl). The number of responders, who had a change in Hb ≥2 g/dl, in group A was 147/249 (67%) compared with 66/108 (61%) in the oral group B (P=0.32). Supplementary Figure 4 demonstrates the proportion of responders over time by dose. Patients, who received >1,000 mg IV iron, had a response rate of 93% (37/40; P=0.0001 when compared with oral iron).

Independent predictor analyses of response (Hb ≥2 g/dl) are illustrated in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. In the IV sub-population, baseline Hb and CRP were significant predictors of response (Supplementary Table 2), whereas there was a trend for total IV iron dose (P=0.097). Hb, TSAT, and disease were significant predictors of response in the oral sub-population where subjects with ulcerative colitis showed a statistically significant higher response than subjects with Crohn's disease (Supplementary Table 3).

Disease activity was measured at screening and week 8, and there was no statistical significant change between groups A and B in change from screening (Supplementary Table 4).

Safety

All safety analyses were conducted on the safety analysis set (N=332).

Both iron isomaltoside 1,000 and oral iron sulfate were well tolerated and the majority of the observed AEs were mild or moderate. No differences between IV administration forms A1 and A2 were found and overall, iron isomaltoside 1,000 was comparable to oral iron sulfate in terms of safety (proportion of patients with AEs in group A: 88/223 (39%); group B: 38/109 (35%); Table 2). adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were observed in 31/223 (14%) in group A and 11/109 (10%) in group B ( Table 2).

Table 2. Number of patients with adverse events.

|

Iron isomaltoside 1,000 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

Infusion (group A1) |

Bolus (group A2) |

Oral iron sulfate (group B) |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Safety analysis set | 223 | 100 | 110 | 100 | 113 | 100 | 109 | 100 |

| Any AEs | 88 | 39 | 46 | 42 | 42 | 37 | 38 | 35 |

| Related AEs | 31 | 14 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 10 |

| Not related AEs | 69 | 31 | 36 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 29 | 27 |

| SAEs | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | <1 |

| Related SAE | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.9 | — | — | — | — |

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious AE.

Supplementary Table 5 provides an overview of the treatment-related AEs (ADRs) in each treatment group. Four patients reported non-serious AEs of hypersensitivity symptoms. In group A1, one patient experienced flushing and hypotension (blood pressure 86/45 5 min after drug administration) on administration of iron isomaltoside 1,000 infusion. In group A2, one patient complained of flushing and respiratory distress lasting 5 min on administration of iron isomaltoside 1,000 bolus injection, a second patient experienced itching and erythematous rashes of moderate intensity in the ears and arms, and a third patient complained of tightness in the chest, breathlessness, anxiety, and diminished vision on administration of iron isomaltoside 1,000 bolus injection. All four subjects experiencing hypersensitivity recovered without sequelae. Two subjects were re-exposed to iron isomaltoside 1,000 without reoccurrence of hypersensitivity reactions. No serious AEs (SAEs) of hypersensitivity were reported.

The proportion of patients withdrawn due to AEs was similar between the treatment groups (group A: 7/225 (3%); group B: 2/113 (2%).

Ten SAEs were reported by nine patients, where eight (out of 223 patients) were in group A and one (out of 109 patients) was in group B. No SAE of hypersensitivity and no anaphylactic shock reactions were reported. All 10 SAEs except 1 (grand mal convulsion from which the patient made full recovery) were considered unrelated to the study drug.

One patient in group A died during the study. The fatal event was considered related to the underlying illness and unrelated to study drug by the investigator. The cause of death was recorded as ulcerative colitis with acute exacerbation, cellulitis of left thigh extending up to left flank, right pneumonia with septic shock, respiratory failure, and metabolic acidosis leading to cardio respiratory arrest. The event occurred 4 days after the patient had been dosed with 250 mg iron isomaltoside 1,000.

No dose–response was seen with the frequency of AEs, SAEs, or ADRs in patients treated with iron isomaltoside 1,000.

The hematological and biochemistry parameters and vital signs at each visit were similar between groups A and B. No clinically significant changes in blood pressure occurred in close relation to the administration of iron isomaltoside 1,000. There was no statistically significant difference in the s-phosphate concentration from baseline to week 8 between groups A and B. The incidence of hypophosphatemia (defined as s-phosphate <2 mg/dl) in group A increased from 1/223 (<1%) at baseline to 11/162 (7%) at week 2 and then decreased to 2/196 (1%) at week 8. In group B, the incidence of hypophosphatemia was 4/109 (4%) at baseline, which decreased to 0/84 and 1/95 (1%) at weeks 2 and 8, respectively. No clinically significant abnormality in electrocardiogram was observed and there was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients who discontinued the study because of lack of response or intolerance to the study drug (group A: 0; group B: 4/113 (3.5%); Figure 1).

A total cumulative dose of 2,500 mg of iron isomaltoside 1,000 as bolus injection was inadvertently administered to a 35-year-old woman. She tolerated the dose well; her hepatic enzymes were transiently elevated to <3 times upper limit of normal, which was considered a minor AE. The elevated hepatic enzyme levels returned to normal within 2 weeks. The patient previously had marginally increased liver enzymes and it was unclear whether the observed increase in liver enzymes was related to the IV iron treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study was a non-inferiority study designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of iron isomaltoside 1,000 compared with oral iron sulfate in IBD patients with IDA. Non-inferiority at week 8 was not demonstrated and we found a trend toward a higher increase with the oral iron compound from baseline in Hb concentration at week 8.

The IV vs. oral iron dosages and study duration are not directly comparable to previous studies, where the iron dosages are lower in this study, which could be a contributing factor to the trend for oral iron inducing a higher increase in Hb than IV iron. However, the hematopoietic response to iron isomaltoside 1,000 is in the range of responses seen with other IV irons (8,11,30,31). In this study, the oral iron sulfate demonstrated a trend toward a higher increase from baseline in Hb concentration at week 8 compared with IV iron isomaltoside 1,000. Previous reported studies are inconsistent in whether IV or oral iron is superior in increasing Hb but in the majority of studies, IV iron is the most effective treatment (8,11,17,30,31). Change in Hb is a well-accepted end point for estimating the efficacy of iron treatment. However, a responder analysis of the number of patients with a relevant increase in Hb might pose an alternative end point. Thus, we performed a post-hoc exploratory responder analysis defined as the numbers of patients with an increase in Hb ≥2 g/dl within 8 weeks. The number of responders was 67% in group A (IV iron isomaltoside 1,000) compared with 61% in group B (oral iron sulfate) with comparable effects on QoL scores in both groups. A subgroup of patients receiving >1,000 mg iron isomaltoside 1,000 (mean 1,313 mg) had a ≥2 g/dl Hb response in 93% of the patients, which points to a dose–response relationship.

The mean change in s-ferritin concentration from baseline to week 8 was significantly higher with IV iron isomaltoside 1,000 compared with oral iron sulfate, which is in line with literature (30), whereas the opposite was observed for the mean change in TSAT. In this study, the TSAT demonstrated large variability in the oral group which may be part of the explanation. Further, it could indicate a more controlled and slow release of bioavailable iron from iron isomaltoside 1,000 to iron-binding proteins with little risk of free iron toxicity (32), where only the amount necessary to cover the need for a satisfying hematopoietic/metabolic response is released from ferritin to transferrin.

The oral Hb response was particularly pronounced in the Indians and this study suggests that regional differences may exist among patients with IBD and IDA. Patients from India had lower baseline Hb, included a higher proportion of men, were more often suffering from ulcerative colitis, and in particular in the oral group, had less often elevated CRP. Hence, the Indian population may have suffered from more pronounced absolute IDA with less severe active inflammation compared with the European population. In fact, literature supports that Asians are more prone to anemia (33).

In general, baseline Hb and CRP were associated with a more pronounced Hb response to both iron treatments as demonstrated in the explorative predictor analysis of responds. Within the treatment groups, subjects with ulcerative colitis showed a statistically significant higher response than subjects with Crohn's disease in the oral group. However, as the analysis of potential predictors was explorative in nature, further studies are required to evaluate potential predictors for response.

In terms of total QoL score, no significant difference in the increase in the QoL score was observed between the treatment groups.

Data in animals suggest that oral iron sulfate may trigger inflammatory processes associated with progression with Crohn's disease-like ileitis (34). In this study, there was no statistical significant change in disease activity from screening to week 8 between groups A and B. However, a longer study period might be needed in order to clarify whether there is a different effect of oral and IV iron on disease activity.

The selection criteria in this study excluding patients with known intolerance to oral iron and severe disease activity may have caused a selection bias toward a favorable tolerability for oral iron. In previous reports, significantly higher percentage of patients (up to 46%) on oral iron discontinued the study because of gastrointestinal disturbances in comparison with patients on IV iron (11%) (35,36). In another study, IBD patients treated with oral iron also reported more gastrointestinal disturbances as compared with IV iron sucrose (21% vs. 5%) (8). Hence, in an unselected IBD population, the tolerability of oral iron would be lower than in this study, where 101 out of 338 patients had been treated previously with oral iron.

Iron isomaltoside 1,000 showed a good safety profile in both up to 500 mg bolus injections over 2 min and up to 1,000 mg IV infusions over 15 min.

ADRs were observed in 14% in group A (IV iron isomaltoside 1,000) and 10% in group B (oral iron sulfate). A single serious ADR of seizures was observed in a patient with no known predisposition to seizures. The mechanism behind the seizure is unknown, but seizures have been described with other IV irons (37). Four non-serious nonspecific hypersensitivity reactions of unclear mechanism, but which may involve complement activation related pseudo-allergy (38), were reported. No anaphylactic shock reactions were observed.

The incidence of patients with transient hypophosphatemia (s-phosphate <2 mg/dl) was 7%, which is low compared with hypophosphatemia rates ranging up to 70% with other IV irons (39). No dose–response was seen with frequency of ADRs and no overall safety concerns were found in vital signs or safety laboratory parameters.

Based on the results from this study, the Ganzoni formula may underestimate the IV iron dose needed when using a target Hb of 13 g/dl and iron stores of 500 mg. This is supported by the exploratory observation that a higher increase in Hb from baseline was observed with dosing of ≥1,000 mg of iron isomaltoside 1,000. In a study by Kulnigg et al. (30), iron carboxymaltose was compared with oral iron sulfate in reducing IDA in IBD. The median Hb improved from 8.7 to 12.3 g/dl in the iron carboxymaltose group and from 9.1 to 12.1 g/dl in the oral iron group, demonstrating non-inferiority (P=0.6967), but not superiority of iron carboxymaltose for the primary end point. Despite that the Ganzoni formula was used for calculation of the iron demand both in the study by Kulnigg et al. and our study, there are major differences which might explain the diverging outcomes and support underdosing in our study. A mean dose of 1,406 mg IV iron carboxymaltose was administered in the study by Kulnigg et al., which was a higher dose compared with the mean dose of approximately 880 mg iron isomaltoside 1,000 given in this study. The large difference in dosing level was most likely due to using either a higher target Hb and/or higher estimate of depot iron in the Ganzoni formula combined with a lower baseline Hb in the study by Kulnigg et al.

In this study, a Hb <12 g/dl and a TSAT <20% were defined as major inclusion criteria, whereas in the study by Kulnigg et al., subjects with a Hb ≤10g/dl and TSAT <20% or s-ferritin <100 μg/l were eligible. Owing to low recruitment, the inclusion criteria of the latter study were modified after 4 months to an Hb ≤11 g/dl. Evaluation of the primary end point in our study was at week 8, whereas in the study by Kulnigg et al. at week 12. Importantly, in the latter study a second treatment cycle was allowed in patients in the iron carboxymaltose group, if their iron status parameters indicated that IDA recurred in between the end of the first cycle and week 9 of the study. The above-mentioned aspects might explain differences in both cumulative iron doses and outcomes between the studies. Thus, only 62% of the iron dose administered in the study by Kulnigg et al. were applied in this study.

Evstatiev et al. (31) applied dosages of 1,377 mg ferric carboxymaltose using an alternative dosing algorithm and 1,160 mg iron sucrose applying the Ganzoni calculation with target Hb 15 g/dl and depot 500 mg and reached response rates for Hb ≥2 g/dl of 65% and 58%, respectively.

As patients treated with >1,000 mg IV iron had a more pronounced Hb response without affecting safety, there seems to be room for higher dosing of iron isomaltoside 1,000. Based on the identified biochemical predictors of response, the main drivers of IV dosing should be Hb and CRP. As safety did not show a dose–response relation, it is suggested that IBD patients with an increase in CRP and Hb <9 g/dl are given higher doses of >1,000 mg IV iron isomaltoside 1,000.

The open-label design of the study may be considered a weakness and needs to be justified. This design is used in several other comparable IBD studies (30,31). It is almost impossible to blind studies where oral iron is compared with IV, as oral iron is indicated by black stools. However, as the primary efficacy parameter was biochemical it is not likely to represent a major limitation. Hence, we consider the study design justified and indicative of important new findings.

In conclusion, we failed to demonstrate non-inferiority of IV iron isomaltoside 1,000 compared with oral iron in our study. However, we provide exploratory evidence that the demand of IV iron was underestimated. Alternative estimates of iron stores including Hb, CRP, and sex should be explored in patients with IBD. Higher doses of iron isomaltoside 1,000 were safe and might have led to superior response rates compared with oral iron in our study.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS

Acknowledgments

We thank all the investigators and study personal for their contribution to the study, and Günter Weiss for his valuable input to interpretation of the iron-related biochemistry.

Guarantor of the article: Walter Reinisch, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions: Michael Staun, Rakesh K. Tandon, Andrew Thillainayagam, and Lars L. Thomsen were involved in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Walter Reinisch, Istvan Altorjay, Cornelia Gratzer, and Sandeep Nijhawan were involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support: The study was funded by Pharmacosmos A/S. Pharmacosmos A/S was responsible for setup of the study, collection, analyses, and interpretation of the data, and in the writing of the report.

Potential competing interest: Lars L. Thomsen is employed by Pharmacosmos A/S, and the investigators/institutions received a fee per patients.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/ajg

Supplementary Material

References

- Wells CW, Lewis S, Barton JR, et al. Effects of changes in hemoglobin level on quality of life and cognitive function in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:123–130. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000196646.64615.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S, Wedel S. Diagnosis and treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1997;3:204–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasche C. Complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasche C, Lomer MC, Cavill I, et al. Iron, anaemia, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2004;53:1190–1197. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iron deficiency anaemia The challenge . http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/ida/en/index.html .

- Wilson A, Reyes E, Ofman J. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116 (Suppl 7A:44S–49S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodemar G, Kechagias S, Almer S, et al. Treatment of anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease with iron sucrose. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:454–458. doi: 10.1080/00365520310008818-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder O, Mickisch O, Seidler U, et al. Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral iron supplementation for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease—a randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2503–2509. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamula P, Piccoli DA, Peck SN, et al. Total dose intravenous infusion of iron dextran for iron-deficiency anemia in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:286–290. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200203000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi LT, Weston CM, Goldfarb NI, et al. Impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000191670.04605.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch W, Staun M, Bhandari S, et al. State of the iron: how to diagnose and efficiently treat iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulnigg S, Gasche C. Systematic review: managing anaemia in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1507–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasche C, Berstad A, Befrits R, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren S, Wikman O, Befrits R, et al. Intravenous iron sucrose is superior to oral iron sulphate for correcting anaemia and restoring iron stores in IBD patients: a randomized, controlled, evaluator-blind, multicentre study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:838–845. doi: 10.1080/00365520902839667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulnigg S, Teischinger L, Dejaco C, et al. Rapid recurrence of IBD-associated anemia and iron deficiency after intravenous iron sucrose and erythropoietin treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1460–1467. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli F, Aljama P, Barany P, et al. Revised European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19 (Suppl 2:ii1–47. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Pajares R, et al. Oral and intravenous iron treatment in inflammatory bowel disease: hematological response and quality of life improvement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1485–1491. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Document, Drug Safety and Risk Management Committee, Division of Medical Imaging and Hematology Products and Office of Oncology Drug Products and Office of New Drugs, New Drug Application (NDA) 22–054 for Injectafer (Ferric Carboxymaltose) for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with heavy uterine bleeding or postpartum patients. 2008.

- Sato K, Nohtomi K, Demura H, et al. Saccharated ferric oxide (SFO)-induced osteomalacia: in vitro inhibition by SFO of bone formation and 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D production in renal tubules. Bone. 1997;21:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Shiraki M. Saccharated ferric oxide-induced osteomalacia in Japan: iron-induced osteopathy due to nephropathy. Endocr J. 1998;45:431–439. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.45.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten BJ, Hunt PJ, Livesey JH, et al. FGF23 elevation and hypophosphatemia after intravenous iron polymaltose: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2332–2337. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten BJ, Doogue MP, Soule SG, et al. Iron polymaltose-induced FGF23 elevation complicated by hypophosphataemic osteomalacia. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:167–169. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.008151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Imamura K, Iida M, et al. Hypophosphatemia induced by intravenous administration of saccharated iron oxide. Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61:99–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01496662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyck DB, Mangione A, Morrison J, et al. Large-dose intravenous ferric carboxymaltose injection for iron deficiency anemia in heavy uterine bleeding: a randomized, controlled trial. Transfusion. 2009;49:2719–2728. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzoni AM. Intravenous iron-dextran: therapeutic and experimental possibilities. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1970;100:301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro Duretter, Produktresume 29 February2012

- Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulnigg S, Stoinov S, Simanenkov V, et al. A novel intravenous iron formulation for treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: the ferric carboxymaltose (FERINJECT) randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1182–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evstatiev R, Marteau P, Iqbal T, et al. FERGIcor, a randomized controlled trial on ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:846–853. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn MR, Andreasen HB, Futterer S, et al. A comparative study of the physicochemical properties of iron isomaltoside 1000 (Monofer®), a new intravenous iron preparation and its clinical implications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;78:480–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005, WHO global database on anaemia, World Health Organization, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. 2008.

- Werner T, Wagner SJ, Martinez I, et al. Depletion of luminal iron alters the gut microbiota and prevents Crohn's disease-like ileitis. Gut. 2011;60:325–333. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.216929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall IC. Strategies for iron supplementation: oral versus intravenous. Kidney Int Suppl. 1999;69:S61–S66. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055suppl.69061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Herzig KA, Gissane R, et al. A prospective crossover trial comparing intermittent intravenous and continuous oral iron supplements in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1879–1884. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.9.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low molecular weight iron dextran (Cosmofer®) summary of product characteristicsdated 27 January2010

- Szebeni J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a new class of drug-induced acute immune toxicity. Toxicology. 2005;216:106–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Public Assessment Report for Ferric Carboxymaltose, TGA Health Safety RegulationMay2011

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.