Abstract

Introduction:

Carcinoma cervix is a leading cause of cancer in India. However, majority of the patients face a problem of not being able to complete the treatment.

Aim:

This study was an attempt to find out the important causes of this non-compliance to treatment in a rural Medical College Hospital where majority of the cancer cases are of cervical cancer.

Results:

Out of 144 patients studied over 2 years 88 cases could not complete the treatment. The study revealed that due old age 58.33% cases were defaulters, having many children at home meant a burden to 76.92% cases and 63.89% cases had a problem of not been able to travel a far distance of more than 100 km from home to hospital for treatment.

Conclusion:

These were the important factors of non-compliance and suggested more important than the issues of literacy and poor socio-economic status.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Non-compliance, Radiotherapy, Socio-demographic factors, Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma cervix is the leading cause of cancer in India. It is estimated that yearly 134,420 Indian women are newly diagnosed with cancer of the cervix[1] and each year the mortality due to this disease is estimated to be around 72,825 Indian women. Most of the cases (85%) present in advanced cases and late stages. Out of these not all cases achieve a complete cure owing to various reasons such as advanced stage, poor differentiated status of histology of the tumor, treatment failures and treatment gaps.

Aim

The present study aims to find out the socio-demographic causes, which lead to non-compliance to treatment even after registration in Radiotherapy (RT) Department of a state government rural Medical College Hospital. This department has got a Co-60 machine for external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and refers patients on a government referral basis to Kolkata (567 km away) for brachytherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a retrospective analysis during the period 2011-2012 conducted at North Bengal Medical College (NBMCH). Total 144 patients were enrolled. All patients were first evaluated by clinical, radiological and laboratory investigations at Gynecology and Obstetrics Department and then by RT Department at NBMCH. All patients were planned for treatment by RT with Co-60 machine (Theratronics International OntarioCanada, Machine ID-1117, Serial no -191). RT was given for 50 Gy in 25 fractions followed by assessment for brachytherapy. Brachytherapy was given at 7 Gy per fraction for 3 weekly by high dose rate (HDR) at RT Department, Kolkata. Concurrent chemotherapy was given to a select group of patients by cisplatin weekly at 40 mg/m2 after assessing, creatinine clearance and other blood parameters such as complete hemogram, random blood sugar and liver function tests. All patients were followed-up regularly.

Inclusion criteria

All patients diagnosed with biopsy proven cervical adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma

Cases of International Federation of Gynecological and Obstetrics (FIGO) Stage IB to IVA

Post-operative carcinoma cervix cases

Patients receiving external radiation at NBMCH followed by brachytherapy at Kolkata.

Exclusion criteria

Patients having metastatic disease

Patients having double primary cancers

Patients having other comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, tuberculosis and autoimmune disorder.

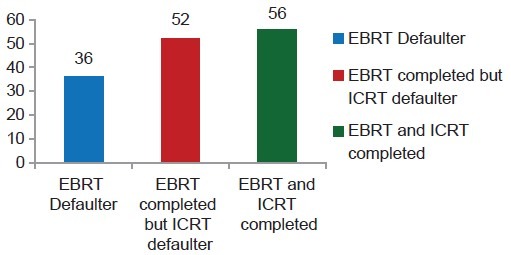

In this retrospective study, the treatment record files of patients who were finally selected according to the exclusion and inclusion criteria, were analyzed with respect to their treatment details. It was noted whether these patients had completed radiation, which comprised of taking the course of EBRT at NBMCH and then brachytherapy at Kolkata. With respect to the treatment adherence and completion, the selected patients were divided into three groups:

1st Group (group A) consisted of those patients who did not take or complete external EBRT after their registration at NBMCH

2nd Group (group B) consisted of those patients who completed EBRT but did not take or complete intracavitary brachytherapy (ICRT)

3rd Group (group C) consisted of those patients who completed EBRT and ICRT.

The factors such as age, parity, menopausal status, monthly income level, level of education, distance from home, which meant time taken and expenses to travel for EBRT were analyzed.

The analysis was performed using simple tests of percentage evaluation and representative bar diagrams and pie charts.

RESULTS

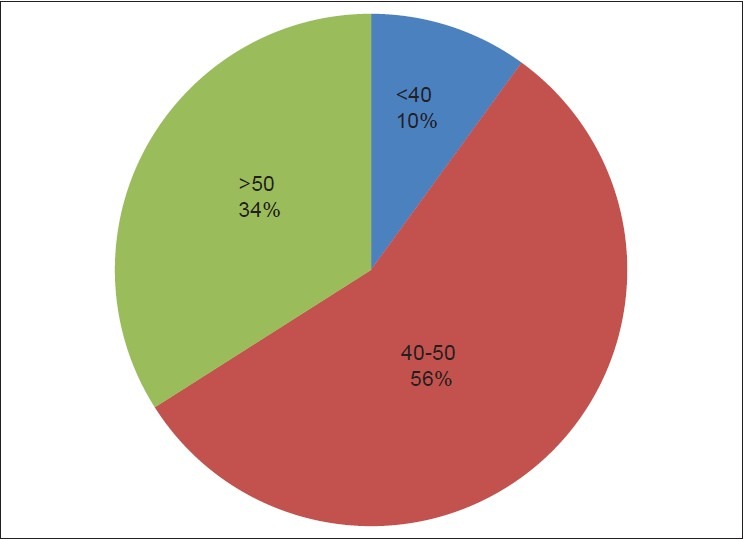

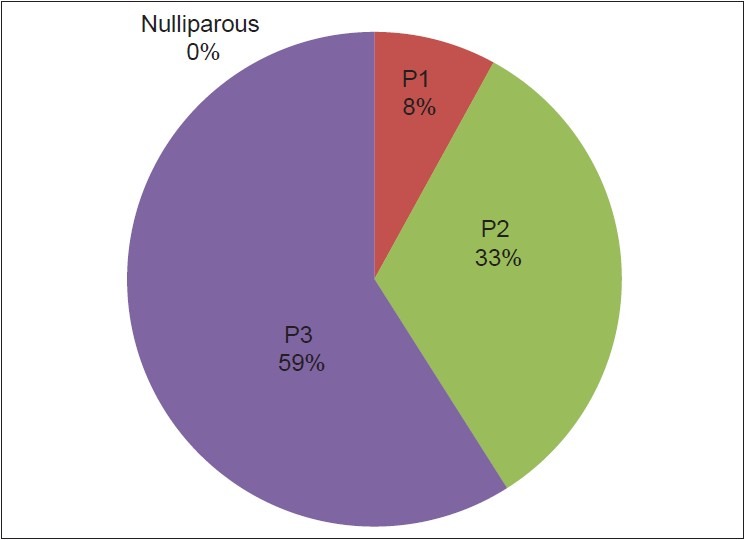

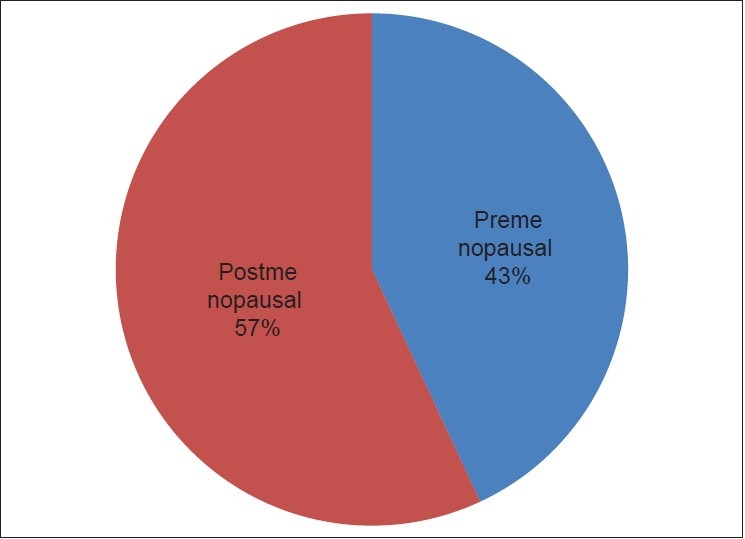

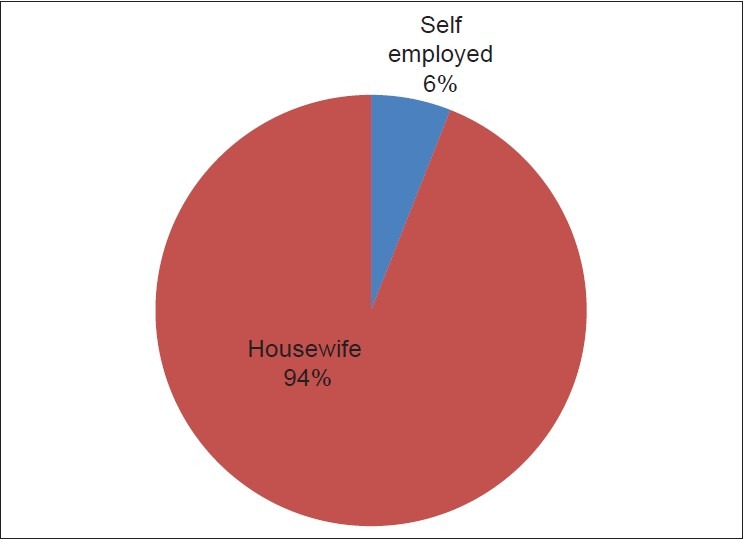

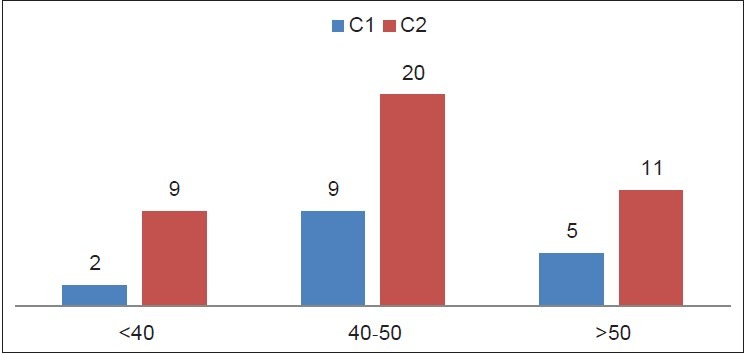

The demographic pattern of the patients is given in Figures 1–6. The lowest age of the presentation was 28 years and the highest age of the presentation was 80 years. Clearly it shows that the majority (55.55%) cases are in the age group of 40-50 years. Majority of the cases were post-menopausal (56.94%) and had a family burden of more than three children (59.02%). Only 6.25% cases were self-employed and the rest had to depend on the family and husband for their livelihood.

Figure 1.

Age

Figure 6.

Group analysis

Figure 2.

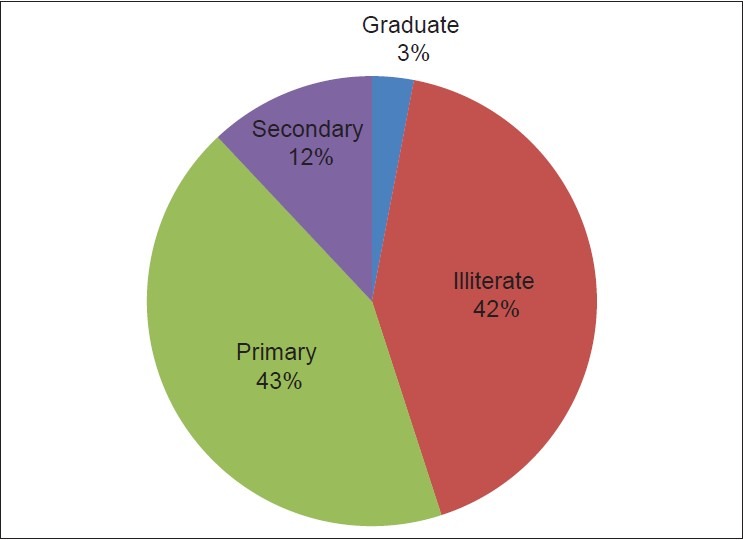

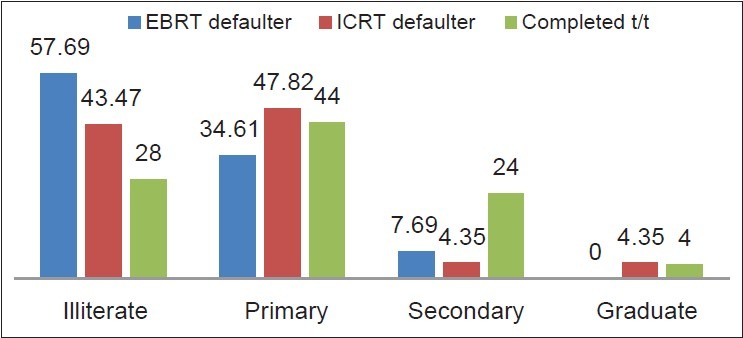

Educational level

Figure 3.

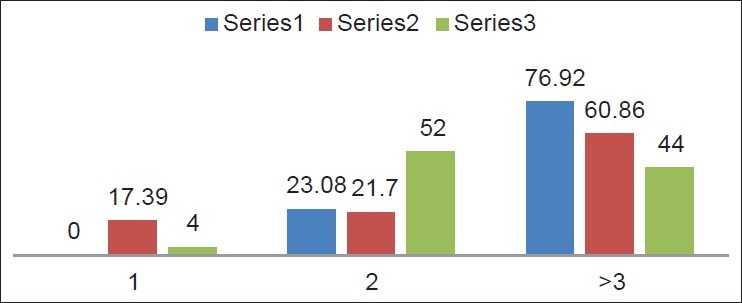

Parity

Figure 4.

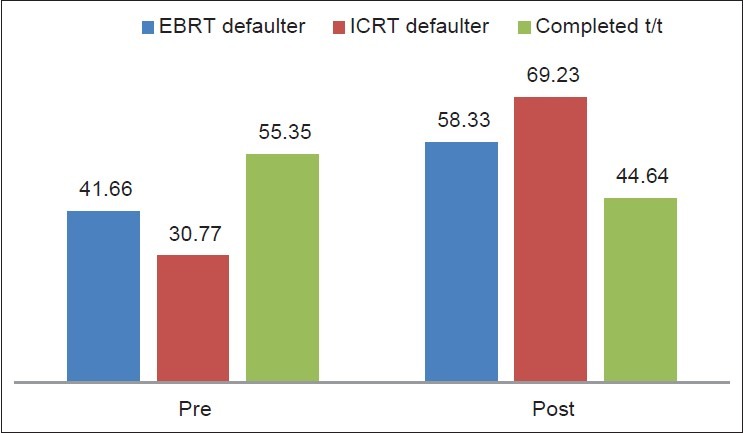

Menopausal status

Figure 5.

Occupation

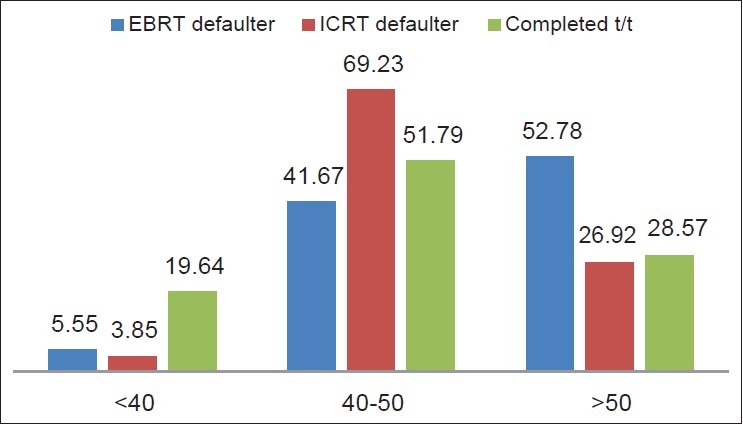

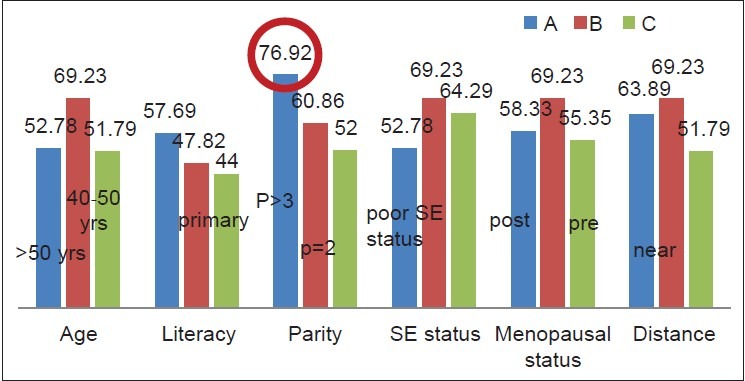

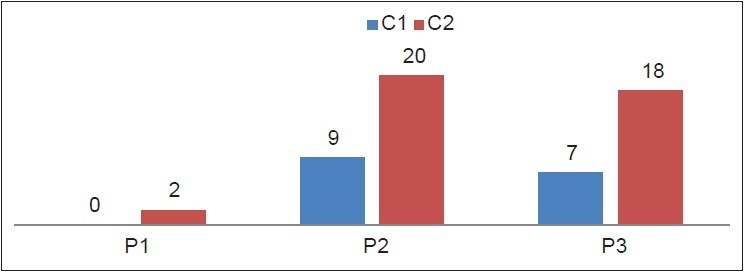

Patients were subdivided into three groups [Figure 6] according to their compliance to treatment. 38.88% of the cases had completed the entire treatment (group C), which comprised of both external radiation and brachytherapy. However, 25% cases did not complete external radiation and 36.11% cases could complete external radiation, but did not comply with brachytherapy in Kolkata. The analysis was carried out to find out the possible important causes of these treatment failures. Comparison of the three groups was performed with respect to six different socio-demographic parameters [Figures 7–12].

Figure 7.

Group analysis age wise

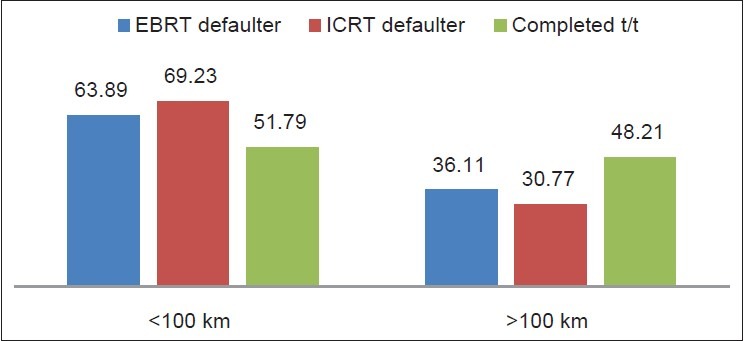

Figure 12.

Group wise analysis of distance

Figure 10.

Group wise analysis of menopausal status

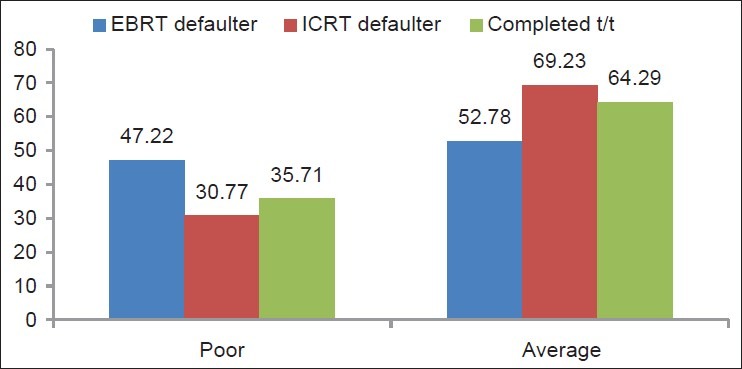

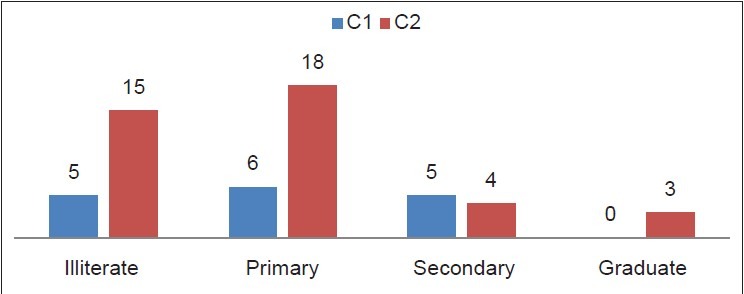

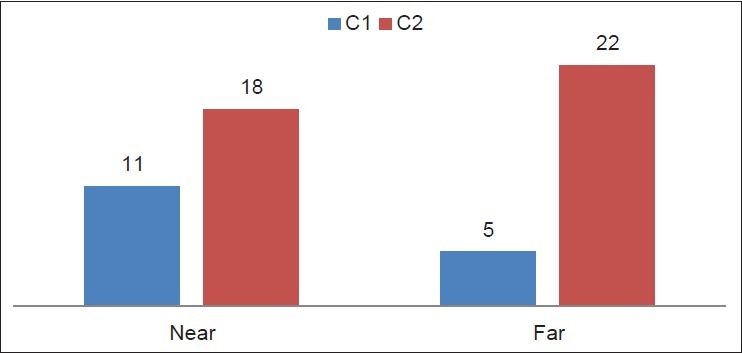

It was found that elderly women (<50 years of age and post-menopausal) belonged to groups A and B, i.e., were defaulters. 52.78% cases were elderly and could not complete EBRT, i.e., group A [Figure 7]. Group A also had the highest number of illiterate women (57.69% cases [Figure 8]. Group A had the maximum number of women who had more than three children at home (76.92% cases) [Figure 9]. Socio-economic status was based on whether the family had a below the poverty line (BPL) card or not. Among the defaulters, it was surprisingly seen that in group B (i.e., those who could not go to Kolkata for brachytherapy) 69.23% cases [Figure 11] were not BPL card holders or not poor. Distance assessment was based on the fact that near = up to 100 km and distant <100 km. It was seen that 63.89% cases of group A and 69.23% cases of group B were not living far, but were the majority of the defaulters [Figure 12]. A matched comparison of all the factors was performed to visualize the highest percentage of cases in each group [Figure 13]. It was found that 76.92% cases of group A had the highest percentage of cases and this was pertaining to the issue of having many children. 69.23% cases of group B (i.e., brachytherapy failures) was the most common and second highest recorded number of cases with respect age 40-50 years, post-menopausal state, of poor socio-economic status and also surprisingly had home nearby.

Figure 8.

Group analysis of literacy

Figure 9.

Group wise parity analysis

Figure 11.

Group wise analysis of socio-economic status

Figure 13.

Matched comparison of all the variables in three groups

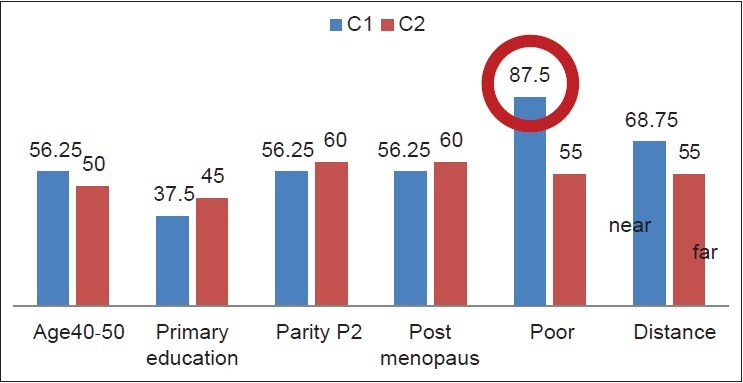

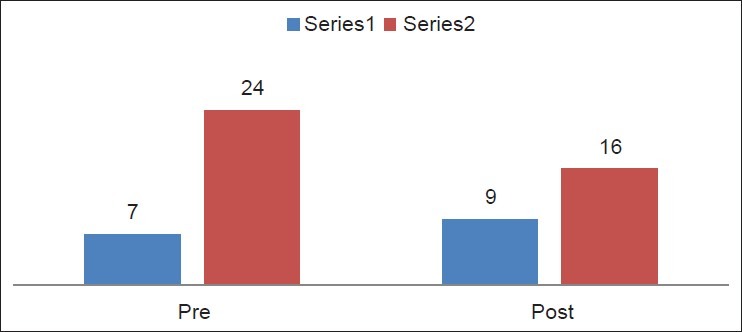

A total of 56 cases had completed treatment. However, we found that even there were two subsets of patients who could complete the entire treatment within 8 weeks and who took a prolonged time to complete the treatment. Further, analysis was performed to find out the issues pertaining to prolonged or delayed treatment [Figures 14–19]. 87.5% cases of group C1, i.e., those who completed the entire treatment in 8 weeks were not poor. 56.25% of cases of group C1 were middle aged, had less number of children (para = 2) and were post-menopausal. However, among those who had prolonged time to complete treatment, 95% had <two children. A matched analysis of both the subgroups C1 and C2 was done [Figure 19] and the data was visualized.

Figure 14.

Age comparison of C subgroups

Figure 19.

Subgroup analysis

Figure 15.

Education status comparison of C subgroups

Figure 16.

Comparison of parity status of C subgroups

Figure 17.

Comparison of menopausal state of C subgroups

Figure 18.

Comparison of distance of C subgroups

DISCUSSION

Carcinoma of the cervix is a leading cause of cancer in India and most of the cases present in FIGO IIB to IIIB.[1] The standard treatment of locally advanced cases of cervical carcinoma is RT with concurrent chemotherapy followed by brachytherapy. To achieve best local tumor control the entire treatment should be completed within 8 weeks.[2],[3] In locally advanced cases classically EBRT is given first and this takes 4-5 weeks to complete. After completion of EBRT, brachytherapy is given weekly once for 2-3 fractions (doses) by HDR and thus it take 2-3 weeks to complete. Usually, a gap of 2-3 weeks is given between completion of external radiation and the start of brachytherapy depending upon the severity of acute toxicity of radiation.

Thus, the entire treatment depends on many factors such as patient's general condition, tolerance to treatment, availability of radiation facility of both EBRT and HDR and radioresponsiveness of the tumor. However, every patient has to stay near the hospital or radiation department for the entire 8 weeks of treatment and this is a very important logistical issue, which is often not emphasized or addressed and this leads to treatment breaks.

The incidence of cervical cancer is greatest among women of lower socio-economic backgrounds. Unquantifiable cultural and individual logistical hurdles such as limited financial, social and personal resources are often significant barriers for receiving treatment.[4],[5] Fear, language, transportation, religious and cultural beliefs may also play a role.[6],[7],[8],[9],[10],[11],[12] These barriers may disrupt patient's desires to complete their treatment, causing prolonged radiation therapy schedules.[13],[14],[15] Consequently cervical cancer has been reported to cause approximately 25% of cancer deaths in certain minority populations.

The RT Department in NBMCH is the only place having a Co-60 machine in the government set-up in the entire North Bengal in the state of West Bengal, India and cancer patients come from six adjoining districts of North Bengal (Malda, Uttar and Dakshin Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Coochbehar, Darjeeling), Sikkim, western districts of Assam (Dhubri, Kokrajhar), Bihar and also from neighboring countries such as Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan for radiation treatment. Hence, the burden of cancer cases registration in RT Out-Patient Department (OPD) is very high per year and is increasing every year. Moreover, after completion of EBRT these patients are referred to Kolkata which is approximately 567 km away from Siliguri (the place where NBMCH is situated) for brachytherapy. All patients are given forms for railway concession for travel from their home place in North Bengal to Kolkata so that they can go for completion of the treatment. Inspite of this not all cases complete EBRT and/or EBRT and brachytherapy. This study was an attempt to find out the possible causes for these failures and to find out steps for ensuring better treatment compliance than the present scenario.

In this study, it has been seen that 25% of cases (group A) did not complete EBRT even after registration at RT OPD. In this group, the highest number of cases had the problem of many children (76.92%). Majority of the cases in this group were elderly (52.78% cases of age <50 years) and post-menopausal (58.33% cases). Hence, it may be speculated that the problem of old age and family burden was definitely a major contributing factor to not complying to EBRT even after starting it. This problem was also seen in the group B (which had completed EBRT but did not go to Kolkata for brachytherapy), i.e., three out of the six assessment factors (age of 40-50 years, poor socio-economic status and post-menopausal status) had 69.23% of cases in each. Even in this group women who had more than three children (60.86%) had the maximum problem of not going for brachytherapy 567 km away. Indeed there was therefore a major link between issues of elderly age, family burden and poor compliance to treatment.

The problem of post-menopusal (56.94%) and elderly women is manifold. Most of the husbands are daily wagers and have children at home who also need care and food to eat. These women mainly look after the general household and the kitchen at home and hence their absence from home for a long time is general difficult to manage for the husband and their children, which ultimately leads to the fact that these women are somehow compelled to return home even if the RT was started.

Since these women are weak with disease and cannot do or help in the household work, they are often a burden to the family of this population. In most of the cases (93.75%), the woman has to depend on husband or any other family member for constant company for travel, stay and complying to needs during EBRT, which is not always possible. Hence, they prefer to stay back at home due to lack of a persistent caregiver.

Almost two-third of the patients live outside the main town and the average time taken to travel is 5-6 h by train or by road. This includes the daily bus fare of atleast two persons up and down, which is not less than Rs. 200 daily, schedule and timing of the conveyance mode which is subjected to weather conditions, road conditions, railways arrival and departure timings coinciding with the hospital OPD hours, holidays and strikes, road and rail blocks. This leads to the fact that inspite of the initial registration at RT OPD these patients find it difficult to travel multiple times for further investigative work-up and getting RT dates before the start of treatment. Hence, this was probably the reason why inspite of the near distance (>100 km) from their respective homes to NBMCH in 63.89% cases of group A and 69.23% cases of (group B) there was poor compliance to treatment. Similar issues of distance and transportation related problems were addressed in studies by Ramondetta et al. from Houston, Texas and Mundt et al. from Chicago and it was shown that a combination of the lack of adequate methods of transportation and social support may contribute to the high cost of treatment in patients with cervical cancer.[16],[17]

Poor socio-economic status was the second common factor in both groups of failures. During EBRT each patient has to stay near the RT Department for 1-1½ months as the hospital does not have any hostel for the patient and family to stay during long-term treatment. Hence each, patient has to take room/house for rent at an average expense of Rs. 1200/month for lodging only excluding daily other expenses for food, clothing, emergency medicines and general household expenses. In order to do this each lady has to either bring her husband or any willing relative of her own in order to accompany her during the EBRT treatment and this doubles up the expenses of food, clothing and other daily needs and this is around Rs. 2000/month. Hence, the total cost of stay for the patient and her family is approximately Rs. 3000-3500. However, poor socio-economic status was a major problem to travel for brachytherapy (69.23%) rather than coming for EBRT at first (52.78% cases).

Surprisingly it was found that 64.29% of cases who had completed the entire treatment (group C) had a poor socio-economic status, i.e., EBRT followed by getting brachytherapy 567 km away. Hence, subgroup analysis of group C was performed to critically further analyze all the six evaluable socio-demographic factors respectively in subgroup C1 (those who completed treatment within 8 weeks) and C2 (<8 weeks to complete).

Only 28.57% cases of group C could complete the treatment within 8 weeks and 87.5% of cases out of these group C1 were not of BPL category. This was the highest percentage of cases recorded in group C1. 71.42% cases were in group C2 and 45% cases of group C2 were of BPL category, which reflected in the broad group C as the majority of cases. Hence, the critical analysis of group C did showed that a high association of good treatment compliance with good socio-economic status in a select subgroup of patients.

Nearly 68.75% cases of group C1 lived near NBMCH compared to 55% cases of group C2 who lived far away when the factor of distance was compared. This also suggested that people living near had to travel less and hence could complete the treatment in time inspite of having a poor socio-economic status.

Women were of middle age (40-50 years) mostly and did not have more than two children at home in both groups C1 and C2. This indirectly reflected that good treatment in young or middle aged women who at the same time did not have a great burden of children.

Literacy was not a very strong decisive factor as reflected from this study as most of the cases in any group were either illiterate or not better than just having primary education and there was no major difference between the number of illiterate (41.66%) women and those who had merely primary education (43.05% cases only).

Factors like advanced age related poor treatment compliance and outcome have been addressed in the study by Brun et al.[18] In January 2005, Trimble et al. had shown that in the US many women with cervical cancer are not treated properly and the factors associated included lack of access to the health-care system, access to a medical specialist, lack of third-party coverage and lack of the necessary social support to help patients be compliant with their medical treatment. In addition, patient's fear and mistrust of the health-care system.[19] made situations more complex practically to ensure treatment. The authors emphasized that “we must implement research to identify the obstacles that may prevent adherence to treatment recommendations.” Similar such studies were performed by authors like Formenti et al. at Los Angeles, Carpenter and Cowell at Texas[20],[21] and suggested several possible reasons like poor understanding of the disease process and the importance of treatment, as well as concerns about transportation, childcare, employment for high rates of non-compliance among inner-city minority patients treated with radiation for cervical cancer.

There has been a lot of emphasis on socio-demographic issues regarding cervical cancer screening program and the current study is our initial attempt in India to address these issues and find out the possible suggestions to ensure proper treatment compliance. However, larger more detailed studies will be needed to clarify the reasons for these failures and to define any solution for better treatment outcome.

The limitations of this study

This study was an initial attempt and probably the first reported study of the issue of non-compliance to RT treatment of cervical cancer in a peripheral rural Medical College Hospital. The relative time period was short Moreover many other factors like linguistics barrier, involvement of other forms of treatment - like homeopathy, ayurvedic or even local tantric or indigenous methods of shedding spells or casts were not included- these could also have been a hindrance to the compliance of treatment. However, this study needs to be carried out for a more prolonged time and include more number of patients so that a proper re-evaluation of more number of important factors leading to non-compliance can be analyzed statistically.

CONCLUSIONS

This study strongly suggests that a family burden of more than three children is a major determinant of poor treatment compliance. Elderly patients tend to be defaulters rather than younger women. Educational status and far distance did not affect the treatment compliance. The best outcome is directly linked with a good socio-economic status though a BPL category does not necessarily mean that she will not comply to treatment.

Hence our suggestions Encourage small family size:

Effort should be made to reduce the undue delay in the investigative work up in radiology and pathology department and in getting Radiation commencement dates. This will ensure lesser number of unwanted travel and expenses

Every effort should be made to increase the facilities of arranging the patient's hostel near to the RT Department at a cheap and subsidized rate from the government so that they can stay with their family during the entire treatment and avoid undue excess expenditure in a limited source of income

Even though, the BPL category patients get free treatment facilities for radiation and chemotherapy; this should be extended in an uncomplicated manner to all patients irrespective of their financial status with regards not only to treatment, but to travel both by rail and specially by road as people hear have to travel long distances by road alone

Small incentives like giving a small cash token amount of money after completing EBRT and brachytherapy can be given as a reward so as to encourage more treatment compliance and goal directed attitude among the patient and the caregivers quite like the concept of mid-day meal for ensuring good formal education among children and also like getting cash money after getting tubal ligation carried out in camps and hospital

Last but not the least every effort made to increase the number of RT centers with basic external beam and brachytherapy facilities in this part of the country so that people have to travel less from their homes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 10 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Accessed on 2012 Feb 11]. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanciano RM, Pajak TF, Martz K, Hanks GE. The influence of treatment time on outcome for squamous cell cancer of the uterine cervix treated with radiation: A patterns-of-care study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:391–7. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Castro-Vita H, Lockett MA. Carcinoma of the uterine cervix. I. Impact of prolongation of overall treatment time and timing of brachytherapy on outcome of radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32:1275–88. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00220-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrahams N, Wood K, Jewkes R. Barriers to cervical screening: Women's and health workers’ perceptions. Curationis. 1997;20:50–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnett CB, Steakley CS, Tefft MC. Barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening in underserved women of the District of Columbia. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:1551–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz VA., Jr Cultural factors in preventive care: Latinos. Prim Care. 2002;29:503–17. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(02)00010-6. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson K, Geiger AM, Mangione CM. Effect of health beliefs on delays in care for abnormal cervical cytology in a multi-ethnic population. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:709–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks SE, Chen TT, Ghosh A, Mullins CD, Gardner JF, Baquet CR. Cervical cancer outcomes analysis: Impact of age, race, and comorbid illness on hospitalizations for invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:107–15. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz A, Eifel PJ, Moughan J, Owen JB, Mahon I, Hanks GE. Socioeconomic characteristics of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with radiotherapy in the 1992 to 1994 patterns of care study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:443–50. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roter DL, Rudd RE, Comings J. Patient literacy. A barrier to quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:850–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konski A, Berkey BA, Kian Ang K, Fu KK. Effect of education level on outcome of patients treated on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 90-03. Cancer. 2003;98:1497–503. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD, Lovejoy B. Why we don’t come: Patient perceptions on no-shows. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:541–5. doi: 10.1370/afm.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen SW, Liang JA, Yang SN, Ko HL, Lin FJ. The adverse effect of treatment prolongation in cervical cancer by high-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2003;67:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyatt RM, Beddoe AH, Dale RG. The effects of delays in radiotherapy treatment on tumour control. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:139–55. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/2/301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yalman D, Aras AB, Ozkök S, Duransoy A, Celik OK, Ozsaran Z, et al. Prognostic factors in definitive radiotherapy of uterine cervical cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24:309–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramondetta LM, Sun C, Hollier L, Jarrett L, Folloder J, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Advanced cervical cancer treatment in Harris County: Pilot evaluation of factors that prevent optimal therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:547–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mundt AJ, Connell PP, Campbell T, Hwang JH, Rotmensch J, Waggoner S. Race and clinical outcome in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with radiation therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:151–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brun JL, Stoven-Camou D, Trouette R, Lopez M, Chene G, Hocké C. Survival and prognosis of women with invasive cervical cancer according to age. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:395–401. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trimble EL, Harlan LC, Clegg LX. Untreated cervical cancer in the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Formenti SC, Meyerowitz BE, Ell K, Muderspach L, Groshen S, Leedham B, et al. Inadequate adherence to radiotherapy in Latina immigrants with carcinoma of the cervix. Potential impact on disease free survival. Cancer. 1995;75:1135–40. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950301)75:5<1135::aid-cncr2820750513>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter V, Colwell B. Cancer knowledge, self-efficacy, and cancer screening behaviors among Mexican-American women. J Cancer Educ. 1995;10:217–22. doi: 10.1080/08858199509528377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]