Abstract

Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy (PPCRA) is an uncommon retinal disorder of unknown etiology that is neither well understood nor classified. We report an atypical case of PPCRA, associated with Coat's like response (CLR) in a 64-year-old man of Asian origin. Both the eyes were involved, though asymmetrically.

Keywords: Coat's like response, pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy, Retinochoroiditis radiata

PPCRA is an uncommon, asymptomatic, slowly progressive disease of unknown etiology, although some authors have attributed it to be the sequela of ocular inflammation. It has been described as pigmentary retinopathy, and is characterized by the presence of bilateral and symmetrical chorioretinal atrophy and corpuscular pigmentation along the retinal veins, extending nearly half to one disc diameter on either side of the vein and its branches.[1]

CLR is characterized by clinical features like telangiectasia, exudation and sometimes exudative retinal detachment.

We report an unusual association of PPCRA with CLR.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man of Asian origin presented to us with complains of slowly progressive defective vision left eye (OS) for five years. There was no history of suggestive of previous inflammation, trauma or nyctalopia, or family history of retinal disorder. He was a known hypertensive on regular treatment.

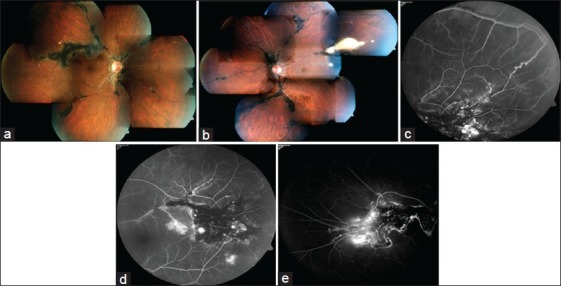

His best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 right eye (OD) and 20/32 OS. Anterior segment was unremarkable both eyes (OU). Central fields were normal. Fundus evaluation showed pigment clumps along the retinal veins with variable chorioretinal atrophy extending from the disc up to equator OU [Fig. 1a and b] and intraretinal and subretinal exudation with telangiectasia along the superotemporal vein OU w(more evident clinically in OS). A clinical diagnosis of PPCRA with CLR, OU was made.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Fundus pictures OD and OS respectively showing pigment clumps along the retinal veins and chorioretinal atrophy extending from the disc, with intraretinal and subretinal exudation and telangiectasia along the superotemporal vein OU (OS is more obvious clinically). (c-e) Fluorescein angiogram OS (c,d) and OD (e) depicting areas of hyperfluorescence in atrophic areas and hypoflourescence corresponding to the pigment clumps with telangiectasia and exudation along superotemporal vein OU and multiple macro aneurysms with capillary nonperfusion areas OS

Electroretinography (ERG) was normal OU. Fluorescein angiography showed areas of hyperfluorescence in atrophic areas in the peripapillary area and hypofluorescence corresponding to the pigment clumps along the retinal veins along with its branches with telangiectasia and exudation along superotemporal vein OU and multiple macro aneurysms with capillary nonperfusion areas OS akin to Coat's disease (CD) [Fig. 1c-e].

Discussion

The first case of this disorder was described as Retinochoroiditis radiata,[2] and since then there have been several reports of varied presentations. The characteristic presentation of PPCRA is bilateral, restricted to the paravenous area, and slowly progressive disorder with macular sparing. Hence, it is believed not to be sight threatening degenerative condition of the eye. Visual field evaluation has been reported to be variable ranging from normal fields to significant field defects. Electrophysiological tests are usually normal but diminution of b-wave and prolongation of a-wave and b wave implicit time have also been described.[3] Although most reports have been of sporadic presentation but there have been reports on hereditary pattern as well.[4]

CLR has been described often in relation to retinitis pigmentosa (RP), and it differs from the classical CD as there is no age and gender predisposition in CLR as opposed to CD where young boys are affected in early childhood. CLR tends to involve inferior and/or temporal quadrants of both retinae in most cases in contrast to CD where the most common involvement is unilateral and in superotemporal quadrant.[5]

Our case is unusual because a bilateral CLR has not been described before with PPCRA, however there has been an earlier report of asymmetric predominantly unilateral PPCRA with microangiopathy, along with field defect in the involved eye, and ERG changes.[6] Our case had no field defects and the ERG was normal OU.

Systemic diseases that may mimic the vasculopathy of this disorder such as diabetes mellitus, retinal vein occlusion, Eales’ disease and sickle cell retinopathy were excluded by history, clinical examination and laboratory investigations.

The cause for vasculopathy cannot be fixed with certainty but an array of clinicopathological explanations for exudative vasculopathy that have been described are an existence of congenital vascular anomalies akin to CD which get stimulated to progress by concurrent degeneration of the retina, choroidal origin for vascular exudative lesions, and acquired degeneration of the Bruch's membrane leading to venous anastomosis between retinal and choroidal vasculature. This exudative vasculopathy leads to a break in the blood retinal barrier resulting in macular edema; and sometimes shallow inferior retinal detachments and subsequent telangiectasia.[7,8]

In our case chronic progressive atrophic changes of retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptors along the retinal veins probably caused a chronic decompensation of the microvasculature leading to telangiectasia, leakage and exudation.

The chronicity of vasculopathy lead to the development of minimal macular edema in OS and the patient had blurring of vision but as the BCVA was too good, no active intervention was contemplated. The cause for subnormal vision OS could not be determined with certainty. Our case expands the clinical spectrum of PPCRA and adds this disease into the list of RP syndromes associated with CLR.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Yamaguchi K, Hara S, Tanifuji Y, Tamai M. Inflammatory pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:463–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.6.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown TH. Retino-choroiditis radiata. Br J Ophthalmol. 1937;21:645–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.21.12.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearlman JT, Kamin DF, Kopelow SM. Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:630–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skalka HW. Hereditary pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87:286–91. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan JA, Ide CH, Strickland MP. Coats’-type retinitis pigmentosa. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:317–32. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limaye SR, Mahmood MA. retinal microangiopathy in pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:757–61. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.10.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fogle JA, Welch RB, Green WR. Retinitis pigmentosa and exudative vasculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:696–702. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050386018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pruett RC. Retinitis pigmentosa: Clinical observations and correlations. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1983;81:693–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]