Abstract

Introduction:

Pharmacovigilance (PV) is designed to monitor drugs continuously after their commercialization, assessing and improving their safety profile. The main objective is to increase the spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), in order to have a wide variety of information. The Italian Drug Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco [AIFA]) is financing several projects to increase reporting. In Calabria, a PV information center has been created in 2010.

Materials and Methods:

We obtained data using the database of the National Health Information System AIFA relatively to Italy and Calabria in the year 2012. Descriptive statistics were performed to analyze the ADRs.

Results:

A total number of 461 ADRs have been reported in the year 2012 with an increase of 234% compared with 2011 (138 reports). Hospital doctors are the main source of this reporting (51.62%). Sorafenib (Nexavar®), the combination of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and ketoprofen represent the drugs most frequently reported causing adverse reactions. Adverse events in female patients (61.83%) were more frequently reported, whereas the age groups “41-65” (39.07%) and “over 65” (27.9%) were the most affected.

Conclusions:

Calabria has had a positive increase in the number of ADRs reported, although it has not yet reached the gold standard set by World Health Organization (about 600 reports), the data have shown that PV culture is making inroads in this region and that PV projects stimulating and increasing PV knowledge are needed.

Keywords: Adverse drug reaction, Italy, ketoprofen, pharmacovigilance, safety

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacovigilance (PV) was born in 1963 after the disaster caused by thalidomide in 1961, with the 16th World Health Assembly (WHA 16.36) that adopted a resolution, which reiterated the need for early intervention with regard to the rapid dissemination of information on adverse drug reactions (ADRs). This led, later, in 1968, to the creation through World Health Organization (WHO) of a pilot research project for international drug monitoring.[1]

The purpose of this was to develop a system, applicable internationally, for detecting previously unknown or poorly understood adverse effects of medicines.[2] From this, practice and science of PV emerged.[3]

PV is defined as the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects and of all other drug problems.[1] Furthermore, the WHO program for international drug monitoring aims at developing a comprehensive global PV strategy that responds to the health-care needs of all countries.[4] As previously stated by the WHA, the WHA 16.36 (1963) led to the creation of the WHO program for international drug control. Under this program, systems have been created in Member States for the collection and evaluation of individual case safety reports (ICSRs).[5]

ADRs knowledge led to increased recognition and reporting of the events. In developed countries, 12% of admissions is caused by ADRs and these are the fourth and the sixth most common cause of death.[6] Furthermore, the increase in the average age of the population is related to a proportional increase in the number of drugs used (due to the prevalence of chronic diseases, such as hypertension, heart failure, glaucoma, prostatic hyperplasia, diabetes, etc.) resulting in an exponential increase of the ADRs.[7] Other possible causes are the rapid development of new molecules for diseases previously intractable and new treatment alternatives for other common pathologies with a significant growth in the number of drugs commercially available. This can generate a lack of health professionals knowledge about the potential adverse effects due to drug-drug interactions or contraindications of some dugs caused by improper use.[8,9,10] Furthermore, the introduction of generic drugs has also increased the number of patients not responding to treatments or with ADRs due to increased bioavailability.[11,12]

In all countries, PV systems rely on spontaneous (or voluntary) communication, in which suspected ADRs are reported by the medical staff or by patients themselves to a national health coordinating center. The spontaneous reporting systems provide the highest volume of information at the lowest maintenance cost[13] and have established their value in the early diagnosis of problems related to safety in patients or their products or their use.[14] Most important function of the spontaneous reporting systems is the early identification of signals[15] and the formulation of hypotheses, which leads to further investigations, in order to confirm or refute any possible risks related to the use of a medication, any possible changes in the package insert and give updated information product.[16]

In some cases, the withdrawal of marketing authorizations are also based on ICSRs, for example, in the case of cerivastatin, an association (a “signal”) among cerivastatin, myopathy and rhabdomyolysis has been published on the basis of ICSRs, from the Uppsala Monitoring Centre in 1999 and various regulatory decisions were announced between 1999 and 2001 in different countries.[17] Unfortunately not in all countries, the voluntary reporting reaches standard levels set by the WHO (300 reported ADRs/1 million people),[18] under-reporting, according to literature data, appear to be due to: Lack of knowledge (it is believed that only serious adverse reactions should be reported), lack of interest or time, the indifference to the problem, the uncertainty about the causal link between a drug and an ADR; the mistaken belief that only safe drugs are marketed.[19] For these reasons, Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) has been promoting several projects on the whole national territory and managed at regional level, in order to increase “PV Culture”.

One of these structures “Regional network of drug information: Information, training and PV” was financed in the Calabria region (located in the south of Italy) at the end of 2010 at “Mater Domini” University Hospital of Catanzaro, in order to increase the scientific skills of health professionals and to inform the community on PV issue, indirectly increasing the number of spontaneously reported ADRs in the region.

The components of this project are carrying out various activities in the whole Calabria regional territory by involving the various training health workers, doctors, pharmacists and structures health facilities. This collaboration has increased the quality and quantity of reports of suspected ADRs and vaccines; AIFA projects by increasing awareness about PV surely help in improving the status of ADRs reporting.

In Italy, the actual situation of spontaneous reports of ADRs is the following: An average annual increase ranging from 25% to 30% in the last 5 years. In the Calabria region, the increase of the signals for 2012 compared with 2011 was of 234%, for 2011 compared with 2010 was 38% while in 2010 there was only an increase of 25% compared with 2009.

In the present study, we report an analysis of the ADRs recorded in 2012 considering various aspects with the hope of stimulating the interest in the PV field and suggesting some possible corrections to improve the system in Calabria or to be used in other countries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All reports of ADR relating to Calabria region were obtained from the database through portal National Health Information System (NSIS) AIFA, a system specifically designed to handle the reporting of ADRs. These reports collected in the year 2012 were studied and analyzed through a descriptive analysis including ADRs severity, the pharmacological class causing ADRs and the kind of reporter. A total of 461 ADRs were present in the database in the period 1st January 2012-31st December 2012.

RESULTS

ADRs analysis

The ADRs’ reports present in the national network of PV via NSIS AIFA, for the year 2012 were totally 461 for Calabria. data analysis showed a higher incidence of ADRs in the age group between 41 and 65 years old, followed by the series “over 65” in part justified by the frequent polypharmacy in patients of this age group. In fact, in the “age 41-65” group, 61 patients of total 180 (33.8%) are in polypharmacy and in the age “over 65” group, 49 patients of total 129 (37.9%) are in polypharmacy; these data confirm the trend of the previous year.[18] In details, in the age group 41-65 the majority of ADRs have been classified as non-serious for the 85.71% while in 14.29% of cases the reaction was severe [Figure 1]. Furthermore, in the age group 0-12 years, ADRs arise in 31 patients, in the age group 13-18 in 11 patients and in the age group 19-40 in 110 patients.

Figure 1.

Frequency of adverse drug reactions in different age range and their related severity

By comparing all age groups the minor onset of ADRs was in the age group 13-18; this is probably due to a reduced use of drugs.

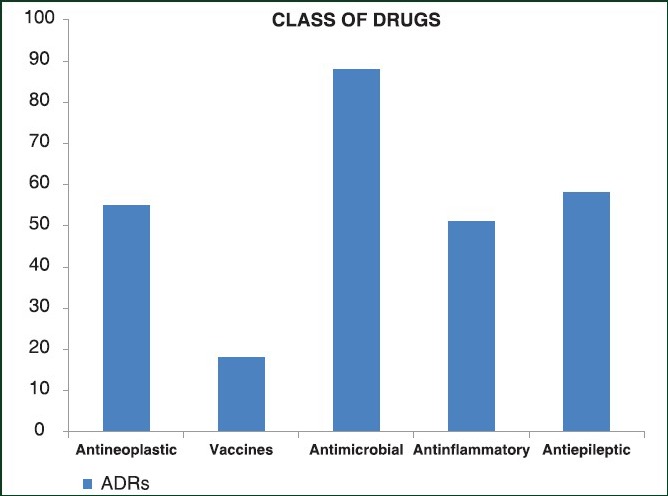

In the age group 41-65, drugs that have given more ADRs were antibacterial agents (16%), followed by anti-inflammatory drugs (10.8%), antiepileptic (10.8%) and antineoplastic (9.14%). In the “over 65” group drugs involved were the antineoplastic (28.24%), the antibacterial (17.55%) and anti-inflammatory (12.97%) [Figure 2]. Furthermore, considering pharmacological class of antimicrobial it is possible to observe a homogenous number of ADRs in all the range age; the antiepileptic drugs have caused the major number of ADRs in the age range of 19-40 [Figure 2]. Furthermore, analysis showed gender differences for the reporting; ADRs in men only account for the 38.17% (number of ADRs 176) whereas a higher number of ADRs for women has been reported (61.83%-285 ADRs reported).

Figure 2.

Number of adverse drug reactions caused by different drugs class in different range age

Considering all ADRs, only the 16.26% was classified as serious [Figure 3]; among drug classes, the highest number of serious adverse events was reported for antibacterial agents (27.27%) followed by anti-inflammatories (23.53%) [Figure 3]. Further analysis showed that the class of drugs, which caused more ADRs, was that of antibacterial agents (19.08%) followed by anti-epileptics (12.58%), antineoplastic (11.93%) and anti-inflammatory drugs (11.06%) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Number of not severe, severe and not definited adverse drug reactions considering different pharmacological classes

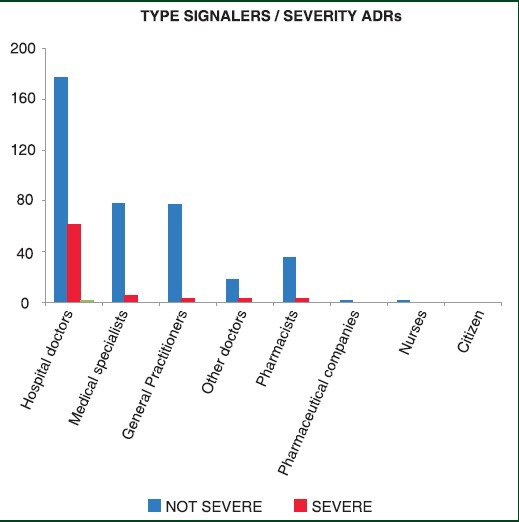

The main class of reporters is represented by hospital doctors with 51.62% of reports, followed by the medical specialists and general practitioners (GPs) with 17.78% and 17.57%, respectively. All health-care groups have reported more non-serious adverse reactions; the hospital doctors have reported the highest number of serious ADRs, specifically, they have reported both 13.23% of serious events and 38.38% of non-serious events comparing all reactions. Considering antibacterials, the association “amoxicillin/clavulanic acid” was the most frequently reported (19.33% of antibacterial and 5,4% of all ADRs reported); on the other hand, when globally considering ADRs the majority of adverse events were caused by the antineoplastic Sorafenib (Nexavar; 6.29% of all drugs), followed by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (5.20%) and ketoprofen (3.27%); the latter two drugs are in trend with the data reported for the year 2011[18] [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Distribution of adverse drug reactions relatively to every single brand name. Nexavar = Sorafenib; OKI = Ketoprofene; Augmentin = Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; Keppra = Levetiracetam; Tegretol = Carbamazepine; Depakin = Valproic acid; Topamax = Topiramate; Taxotere = Docetaxel; Rocefin = Ceftriaxone; Clavulin = Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; Zimox = Amoxicillin

From the comparison between brands and generics, it has been found that only 52 of 461 (11.2%) ADRs were caused by generic drugs use while the rest was caused by brand drugs. The most frequently reported reactions were skin reactions (132 ADRs) followed by gastrointestinal reactions and lack of efficacy [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Incidence of the most frequently reported type of adverse drug reactions

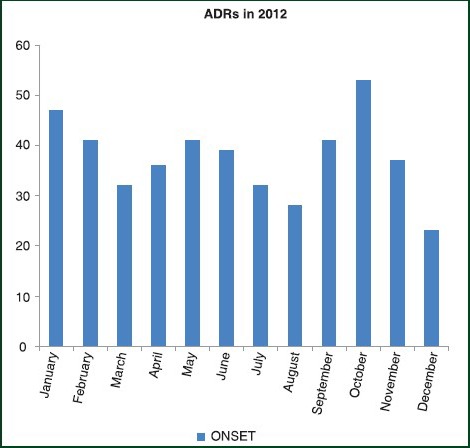

Last analysis examined the occurrence of ADRs for each month during 2012 [Figure 6]. Distributing ADRs relatively to the month of observation, the mean number of ADRs/month was 37.5; furthermore, it was observed that October and January represent the months with the higher number of ADRs whereas, August and December are below the average/month.

Figure 6.

Number of adverse drug reactions in the months of 2012

DISCUSSION

In Calabria 2,011,395 people live therefore, according to the standards set by the WHO (300 reports/million population), the number of ADR/year should be around 603. For the year 2012 were totally 461 for Calabria, with a marked increase in comparison to previous years; the increase was 234% compared with 2011 and by 476% compared with 2010. The positive trend of spontaneous reporting in the Calabria region started in 2011;[18] in 2012 has obtained a positive result which is very encouraging for 2013; the WHO standard has not been reached; however, the mechanism set up has already collected in 2013 about 400 ADRs report on the 10th of May. Up to date, the number is already very close to the previous year and very likely it will lead to about 800 reports for 2013.

This result was achieved by an intensive activity of information to health professionals by the organization of 5 regional update courses on PV. Furthermore, informative leaflet and advertisement on the role of the PV center and the importance of PV has been pursued at all levels including brief meetings in hospitals or publications on newspapers. Finally, a strong collaboration based on selected local project has led to the creation of small professional networks paying particular attention to the development of ADRs and drug safety. All together, the continuous feedback obtained by health professionals increased the general knowledge on PV.

In relation to the source's signal, it is also observed in 2012 a high participation of specialist doctors mainly working in hospitals and general practitioners; very relevant is the increase observed for pharmacists in comparison to the previous year (39 in the 2012 while 7 in the 2011). Whereas, reports by nurses remains very low despite the fact that them together with pharmacist might be considered the first to observe possible ADRs; furthermore, no spontaneous reports from patients were uploaded into the system. The reasons for such a result might be various (see below); however, in some cases nurses observed the ADR and then the physician reported it, whereas despite the increment in the number of reports by pharmacists, this class could undoubtedly increase their participation to the system. These data, although many measures have been put in place to increase the PV culture at regional, national and global levels, it must be admitted that still more job has to be done in order to move out of this under-reporting condition.

Under-reporting has many causes: The detectors often look for a certain temporality and causality between ADRs and drug before reporting the event; sometimes the reports are of poor quality or incomplete and cannot be inserted into the system; there is an underutilization of the latest technological communication means; very often the reporters complain about the lack of time to fill in ADRs.[20]

In Italy, in 2012, the total number of ADRs has been 29,036 with an increase of 35% in comparison to 2011 and 44% in comparison to 2010. Therefore, in Italy, 473/million inhabitants ADRs were reported keeping Italy beyond the standard set by WHO. Although the gold standard (GD) has been achieved at national level, the number of reports is not homogenous in the country and there are regions that exceed the GD and other, which are far below.

Among the various Italian regions, a strong discrepancy can be evidences; in fact, there are regions such as Lombardia, which holds the largest number of signals with 11.639 reports in 2012 (1194/million) and 9170 in 2011, followed by Toscana (4.446 in 2012 = 1186/million), Piemonte (2102 in 2012 = 470/million) and Campania (1839 = 319/million in 2012). On the hand, there are regions such as Friuli Venezia Giulia (364 in 2012 = 294/million), Veneto (1407 = 284/million in 2012) and Calabria (461 = 230/million in 2012) that are close to the GD and finally, there are regions still far from reaching the GD such as Lazio (920 in 2012 = 166/million), Sicily (797 in 2012 = 158/million) and Liguria (203 in 2012 = 129/million).

The largest increases were observed in Puglia (+258%), Calabria (+243%), Piemonte (+205%) and Abruzzo (+100%) where new active centers of PV started their work or were maintained. These data demonstrate the importance of the role of projects financed by AIFA and indicate that this system can be implemented as a result of an appropriate intervention policy. The number of professionals that send signals is still low, but the increase of reports recorded in 2012 is a sign that the world medical-health is sensitive to the problem; surely all the interventions put in place in recent years have increased PV culture.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Italy at national level has reached and exceeded the GD pre-set by the WHO and has shown an important growth signal, an increase of reports of 35% over the previous year was observed. In addition, 80% of the Italian regions had an increase in the total number of ADRs. The region Calabria has demonstrated to be booming in the field of PV despite not having reached yet the GD it has shown one of the largest increase.

The positive trend is encouraging and the work of the regional center is reaching satisfactory levels. The activities organized in the last 2 years such as various continuing medical education (CME) courses, have led to good results (the current ADRs count for this year is very encouraging). More generally, the role of PV regional centers seems to be necessary to the correct functioning of this machine. In the past, when such centers activities were stopped, due to lack of funding, the number of ADRs dropped down to unsatisfactory levels. Therefore, information and support must continue in the next coming years at least until PV culture gets a widespread diffusion starting to be self-sustained. In any case, the relevance of PV to patients’ safety and pharmaco-economy should be a primary aim in all countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The Italian Drug Agency AIFA is kindly acknowledged for its financial and technical support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Last accessed 30th of April 2013]. World Health Organization. The Importance of Pharmacovigilance – Safety Monitoring of Medicinal Products. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4893e/s4893e.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1972. International Drug Monitoring: The Role of National Centres (WHO) Technical Report Series No. 498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bankowski Z, Dunne JF, editors. Geneva, Switzerland: CIOMS; 1994. Drug surveillance: International co-operation past, present and future. Proceedings of the XXVIIth CIOMS Conference. 14-15 September 1993; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsson S, Pal SN, Stergachis A, Couper M. Pharmacovigilance activities in 55 low- and middle-income countries: A questionnaire-based analysis. Drug Saf. 2010;33:689–703. doi: 10.2165/11536390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pal S, Dodoo A, Mantel A, Olsson S. The World Medicines Situation 2011. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2011. Pharmacovigilance and Safety of Medicines. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rambhade S, Chakarborty A, Shrivastava A, Patil UK, Rambhade A. A survey on polypharmacy and use of inappropriate medications. Toxicol Int. 2012;19:68–73. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.94506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strandell J, Norén GN, Hägg S. Key elements in adverse drug interaction safety signals: An assessment of individual case safety reports. Drug Saf. 2013;36:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s40264-012-0003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallelli L, Staltari O, Palleria C, Di Mizio G, De Sarro G, Caroleo B. A case of adverse drug reaction induced by dispensing error. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19:497–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patanè M, Ciriaco M, Chimirri S, Ursini F, Naty S, Grembiale RD, et al. Interactions among low dose of methotrexate and drugs used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/313858. 313858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vuono A, Scicchitano F, Palleria C, Russo E, De Sarro G, Gallelli L. Lack of efficacy during the switch from brand to generic allopurinol. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013;20:540–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vuono A, Palleria C, Scicchitano F, Squillace A, De Sarro G, Gallelli L. Development of skin rash during the treatment with generic itraconazole: Description of a case. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013 doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.130086. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma M, Gupta SK. Postmarketing surveillance. In: Gupta SK, editor. Textbook of Pharmacovigilance. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2011. pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alj L, Touzani MD, Benkirane R, Edwards IR, Soulaymani R. Detecting medication errors in pharmacovigilance database: Capacities and limits. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2007;19:187–94. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Härmark L, van Grootheest AC. Pharmacovigilance: Methods, recent developments and future perspectives. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64:743–52. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke A, Deeks JJ, Shakir SA. An assessment of the publicly disseminated evidence of safety used in decisions to withdraw medicinal products from the UK and US markets. Drug Saf. 2006;29:175–81. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. WHO international drug monitoring: cerivastatin and gemfibrozil. WHO Drug Inf. 2002;16:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scicchitano F, Giofrè C, Palleria C, Mazzitello C, Ciriaco M, Gallelli L, et al. Pharmacovigilance and drug safety 2011 in Calabria (Italy): Adverse events analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:872–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Gonzalez E, Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A. Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32:19–31. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards IR. Pharmacovigilance. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:979–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]