Abstract

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of refractive errors in Yazd, central Iran.

Methods

This population-based study was performed in 2010-2011 and targeted adults aged 40 to 80 years. Multi-stage random cluster sampling was applied to select samples from urban and rural residents of Yazd. Manifest refraction, visual acuity measurement, retinoscopy and funduscopy were performed for all subjects. Myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism and anisometropia were defined as spherical equivalent (SE) <-0.50 diopters (D), SE >+0.50 D, cylindrical error >0.5 D and SE difference ≥1 D between fellow eyes, respectively.

Results

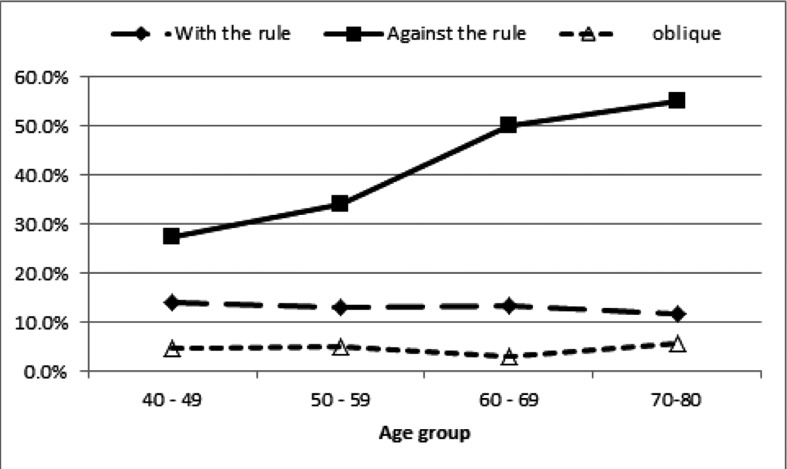

From a total of 2,320 selected individuals, 2,098 subjects (90.4%) participated out of which 198 subjects were excluded due to previous eye surgery. The prevalence (95% confidence interval) for myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, anisometropia, -6 D myopia or worse, and 4 D hyperopia or worse was 36.5% (33.6-39.4%), 20.6% (17.9-23.3%), 53.8% (51.3-56.3%), 11.9% (10.4-13.4%), 2.3% (1.6-2.9%) and 1.2% (0.6-1.8%), respectively. The prevalence of hyperopia, astigmatism and anisometropia increased with age. The prevalence of myopia was significantly higher in female subjects. The prevalence of with-the-rule, against-the-rule and oblique astigmatism was 35.7%, 13.4% and 4.6%, respectively. The prevalence of against-the-rule astigmatism increased with age (P<0.001); with-the-rule astigmatism was more common in women (P=0.038).

Conclusion

More than half of the study population had refractive errors; the prevalence of myopia and astigmatism was higher than earlier studies in Iran. Since refractive errors are a major cause of avoidable visual impairment, their high prevalence in this survey is important from a public health perspective.

Keywords: Population-based Study, Myopia, Hyperopia, Astigmatism, Anisometropia, Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Uncorrected refractive errors are the leading cause of low vision and the second cause of blindness worldwide.1 One hundred and fifty- three million individuals are visually impaired due to refractive errors, of whom 8 million are blind.1 Smith et al demonstrated that refractive errors impose a huge financial burden on human societies.2 Refractive errors affect people of all ages and have been reported in more than 60% of subjects over 40 years of age3-6 and in more than 20% of students7-9. There are new reports released each year on the prevalence of refractive errors and their possible causes, yet, our knowledge on their pattern of distribution and affecting factors is scarce. While it has already been revealed that the prevalence of myopia is particularly high in East Asian countries10-12, there is no recognized region as a reference when referring to hyperopia. Roles of genes and environmental factors such as near work have already been explained for uprising myopia; however results have been inconsistent regarding the association between near work and myopia in more recent studies.13-16 Despite the availability of numerous surveys on refractive errors, due to their high prevalence, further studies are still necessary in different parts of the world.

In the past decade, a number of studies have been conducted among students and elderly subjects in Iran showing hyperopia to be more prevalent than myopia.6,17-20 Nevertheless, to come up with the hypothesis that Iran is an accumulation spot for hyperopia, more surveys should be performed in different parts of the country. Regarding the fact that the elderly are at higher risk of visual impairment, they comprise the priority group for performing these studies.

The current cross-sectional population based survey was performed in 2010-2011 on the elderly population of Yazd; earlier reports on design study and protocol and the prevalence of glaucoma have been published elsewhere.21,22 Herein, we report age- and sex- adjusted prevalence rates for myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism and anisometropia.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was performed in 2010-2011 on 40 to 80 year-old inhabitants of Yazd which is one of the central districts in Iran. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

The methodology of this survey has been discussed in another report21, nevertheless, herein we briefly explain the applied sampling method. Subjects were selected through multi- stage random cluster sampling. Proportionate to urban and rural non-institutionalized populations based on the national 2006 census, 58 clusters including 52 urban and 6 rural clusters were selected. Six trained interviewers invited subjects to participate in the study at their residence. Selected subjects were interviewed face to face to record certain demographics including age, gender, education, and drug and medical histories. Written informed consent was obtained from those willing to participate in the study prior to enrollment.

All participants underwent manifest refraction, uncorrected and best corrected visual acuity measurement, retinoscopy and funduscopy. Visual acuity measurement was performed by an optometrist using a NIDEK chart projector (CP-670 20/10- 20/400; Nidek Co, Gamagori, Japan) with tumbling E letters at a distance of 4 meters. Refraction was measured by an optometrist using a Topcon automated refractometer (Topcon KR 8000, Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The results were used as a starting point for a full subjective and manifest refraction. If autorefraction was not possible, manual manifest and subjective refraction were tried. Subjects with history of eye surgery were excluded from the current analysis.

Spherical equivalent (SE) was applied to define refractive errors in this study and was described as sphere power plus half cylinder power. Similar to previous studies,5,10,23,24 myopia and hyperopia were defined as SE of worse than -0.50 diopters (D) and +0.50 D, respectively. SE of -0.50 D to +0.50 D was defined as emmetropia while astigmatism was defined as cylinder power exceeding 0.5 D. In order to demonstrate the severity of refractive errors, myopia of -6.00 D or worse and hyperopia of 4.00 D or worse were also reported. The prevalence of refractive errors was reported both binocularly and monocularly for all participants. In order to be considered as a subject with refractive error, the participant had to have a refractive error in at least one eye. In cases with one myopic and a fellow hyperopic eye, the refractive error of the eye with larger absolute SE was taken into account. Astigmatism was classified according to the 30 degree axis rule,25-26 negative cylinder axes within 0±30 degrees and 90±30 degrees were considered as with-the-rule and against-the-rule astigmatism, respectively; other axes were categorized as oblique astigmatism. Anisometropia was defined as a difference of at least 1D in SE between fellow eyes.27-29. SE difference in subjects with two myopic/ hyperopic eyes was defined as anisomyopia/ anisohyperopia.

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence rates for myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism and anisometropia were reported with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). The design effect of cluster sampling was considered in calculating the standard error and 95%CIs. Age- and sex- standardized prevalence values based on the 2006 National Census were also reported. Logistic regression analysis using STATA V11 software was applied for evaluating the relationship between risk factors and refractive errors. Relationships among all risk factors were analyzed by backward multiple logistic regression model. Significance level was set at 5%.

RESULTS

From a total of 2,320 invited individuals, 2,098 subjects participated in the survey (response rate of 90.4%) consisting of 994 (47.4%) male subjects. A total of 198 (9.4%) subjects were excluded due to previous ophthalmic surgeries. Mean age of the participants was 53.2±9.54 years and mean SE was 0.53D (95%CI, 0.39-0.66D).

Myopia

Binocular and monocular myopia was observed in 25.2% (95%CI: 22.7-27.7%) and 11.6% (95%CI: 10.1-13.2%) of the study population, respectively; the prevalence of myopia in at least one eye considering an SE of ≤-0.5 was 36.5% (95%CI: 33.6-39.4%).

The prevalence of different types of refractive errors are summarized in table 1. Logistic regression analysis revealed that the odds of being myopic was significantly higher in women (odds ratio [OR]=1.23, 95%CI: 1.03- 1.47, P=0.023). The prevalence of myopia did not significantly vary in different age groups (P=0.106). Regarding 40-49 year-old subjects as our reference group, the odds of being myopic among 50-59 (P=0.061) and 60-69 (P=0.056) year-old subjects were marginally lower than that of 40-49 year-old individuals (Table 1). There was no significant difference in terms of myopia among different levels of literacy (P=0.234). Table 2 presents logistic regression results on myopia and education. Logistic regression analysis revealed that location of residence had no significant relationship with myopia (P=0.269), neither did nuclear cataracts (P=0.426).

Table 1.

Prevalence of myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism and anisometropia with a CI of 95% in the study population.

| Number | Myopia* % (range) | Hyperopia* % (range) | Astigmatism* % (range) | Anisometropia* % (range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||||

| 40 to 49 | 780 | 39.0 (35.2-42.8) | 8.7 (6.5-10.9) | 46.3 (42.3-50.3) | 8.1 (6.2-10.0) | |

|

|

||||||

| 50 to 59 | 656 | 34.4 (30.5-38.2) | 23.2 (19.6-26.8) | 52.3 (48.4-56.2) | 10.2 (8.0-12.5) | |

|

|

||||||

| 60 to 69 | 290 | 33.1 (27.8-38.5) | 33.8 (27.7-39.9) | 66.6 (60.4-72.7) | 16.2 (11.7-20.7) | |

|

|

||||||

| 70 to 80 | 172 | 39.5 (31.7-47.4) | 42.4 (33.6-51.3) | 72.7 (65.4-79.9) | 28.5 (21.6-35.4) | |

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| female | 995 | 38.8 (35.0-42.6) | 18.6 (15.4-21.8) | 54.9 (51.7-58.0) | 11.7 (9.7-13.6) | |

|

|

||||||

| male | 905 | 34.0 (30.7-37.2) | 22.8 (19.5-26.1) | 52.6 (49.0-56.2) | 12.2 (9.9-14.4) | |

|

| ||||||

| Place | ||||||

| urban | 1686 | 35.8 (32.9-38.7) | 19.9 (17.1-22.7) | 53.0 (50.3-55.7) | 11.4 (10-12.9) | |

|

|

||||||

| rural | 214 | 41.8 (31.3-52.3) | 25.8 (16.7-35.0) | 59.8 (56.4-63.3) | 15.4 (8.8-22.0) | |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| illiterate | 338 | 37.0 (32.3-41.7) | 32.2 (26.3-38.2) | 65.1 (60.1-70.1) | 18 (13.7-22.4) | |

|

|

||||||

| primary | 789 | 38.2 (34.4-42.0) | 17.4 (13.9-20.9) | 56.4 (52.6-60.2) | 10.5 (8.2-12.8) | |

|

|

||||||

| secondary | 221 | 29.9 (23.4-36.3) | 21.3 (14.5-28.1) | 45.7 (39.4-52.0) | 10.0 (6.0-13.9) | |

|

|

||||||

| diploma | 320 | 35.9 (29.7-42.2) | 16.6 (12.8-20.3) | 46.9 (41.2-52.6) | 10.0 (6.7-13.3) | |

|

|

||||||

| academic | 218 | 37.2 (30.9-43.4) | 19.3 (12.8-25.8) | 45.4 (39.6-51.3) | 11.0 (6.6-15.5) | |

|

| ||||||

| Total prevalence | ||||||

| crude | 1900 | 36.5 (33.6-39.4) | 20.6 (17.9-23.3) | 53.8 (51.3-56.3) | 11.9 (10.4-13.4) | |

|

|

||||||

| age sex standardized | 36.3 (33.3-39.2) | 18.8 (16-21.5) | 52.2 (49.5-54.9) | 11.3 (9.8-12.8) | ||

All values are reported with a confidence interval of 95%

Table 2.

Relationship among different refractive errors in a simple logistic regression model according to the studied variables.

| Myopia | Hyperopia | Astigmatism | Anisometropia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Gender Male=0, Female=1) | 1.23 (1.03-1.47) | 0.023 | 0.77 (0.62-0.96) | 0.022 | 1.1 (0.91-1.31) | 0.318 | 0.95 (0.73-1.25) | 0.728 |

|

| ||||||||

| Area (Urban=0, Rural=1) | 1.29 (0.82-2.02) | 0.269 | 1.4 (0.84-2.33) | 0.192 | 1.32 (1.1-1.58) | 0.003 | 1.41 (0.83-2.39) | 0.196 |

|

| ||||||||

| Nuclear cataract No=0, Yes=1) | 1.67 (0.46-6.1) | 0.426 | 0.63 (0.14-2.76) | 0.533 | 0.88 (0.26-2.96) | 0.836 | 2.31 (0.69-7.70) | 0.168 |

|

| ||||||||

| Age (years) | Not linear | 1.07 (1.06-1.09) | <0.0001 | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | <0.0001 | 1.05 (1.04-1.07) | <0.0001 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 40-49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 50-59 | 0.82 (0.66-1.01) | 0.061 | 3.16 (2.46-4.06) | <0.0001 | 1.27 (1.03-1.57) | 0.027 | 1.29 (0.89-1.89) | 0.175 |

|

| ||||||||

| 60-69 | 0.77 (0.6-1.01) | 0.056 | 5.34 (3.46-8.25) | <0.0001 | 2.31 (1.64-3.25) | <0.0001 | 2.2 (1.45-3.34) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| 70-80 | 1.02 (0.76-1.38) | 0.877 | 7.72 (4.91-12.15) | <0.0001 | 3.09 (2.15-4.44) | <0.0001 | 4.53 (3.13-6.58) | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Illiterate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Primary | 1.05 (0.84-1.32) | 0.646 | 0.44 (0.31-0.62) | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.53-0.92) | 0.011 | 0.53 (0.36-0.78) | 0.002 |

|

| ||||||||

| Secondary | 0.73 (0.51-1.03) | 0.069 | 0.57 (0.35-0.91) | 0.019 | 0.45 (0.32-0.63) | <0.0001 | 0.5 (0.3-0.83) | 0.008 |

|

| ||||||||

| Diploma | 0.96 (0.7-1.3) | 0.77 | 0.42 (0.29-0.61) | <0.0001 | 0.47 (0.35-0.65) | <0.0001 | 0.5 (0.3-0.85) | 0.011 |

|

| ||||||||

| Academic | 1.01 (0.73-1.38) | 0.963 | 0.5 (0.31-0.82) | 0.007 | 0.45 (0.32-0.62) | <0.0001 | 0.56 (0.33-0.96) | 0.036 |

After analyzing the variables (age, gender, nuclear cataracts, literacy level and residence) in a multiple logistic model, it was clarified that female gender has a significant relationship with myopia. Figure 1 demonstrates the severity of myopia and hyperopia. The prevalence of 6 D or worse myopia was 2.3% (95%CI: 1.6-2.9%) in the current study.

Figure 1.

Severity of myopia and hyperopia by gender in the elderly population of Yazd district, Iran.

Hyperopia

The prevalence of binocular and monocular hyperopia was 12.5% (95%CI: 10.7-14.2%) and 8.6% (95%CI: 7.2-10.0%), respectively; the prevalence of hyperopia in at least one eye considering SE ≥0.5 D was 20.6% (95%CI: 17.9- 23.3%). The prevalence of hyperopia was lower in men (Table 1). Logistic regression showed that the odds of being hyperopic was significantly lower in women (OR=0.77, 95%CI: 0.62-0.96%, P=0.022).

The lowest prevalence of hyperopia was observed in 40-49 year-old subjects with a corresponding value of 8.7%. The prevalence of hyperopia increased with age (Table 1); it was 23.2%, 33.8% and 42.4% in 50-59, 60-69 and 70-80 year-old individuals, respectively. Each year of increase in age raised the odds of hyperopia by 7% (P<0.001).

Considering different levels of literacy, the highest odds of being hyperopic was observed among illiterate subjects (Tables 1); referring to this group as a reference in logistic regression analysis, the prevalence of hyperopia was significantly lower with other levels of literacy.

It was also revealed that only age had a direct relationship with the prevalence of hyperopia (P<0.001). The prevalence of ≥4 D of hyperopia was 1.2% (95%CI: 0.6-1.8%).

Astigmatism

The prevalence of bilateral and unilateral astigmatism was 31.4% (95%CI: 29.3-33.6%) and 22.4 (95%CI: 20.3-24.4%), respectively; the prevalence of astigmatism in at least one eye was 53.8% (95%CI: 51.3-56.3%) which was not significantly (P=0.318) different in men and women, (Tables 1 and 2). The prevalence of astigmatism increased significantly with age (OR=1.04, 95%CI, 1.03-1.05, P<0.001).

The prevalence of astigmatism was significantly higher among illiterates as compared to other levels of literacy (Table 1 and 2). Multiple regression analysis revealed a direct relationship between age and astigmatism; in addition, the prevalence of astigmatism was significantly lower in people with high school diploma or higher levels of education as compared to illiterates (Table 2).

The prevalence of astigmatism was significantly higher in people living in rural areas (P=0.003). The prevalence of against-the- rule, with-the-rule and oblique astigmatism was 35.7%, 13.4% and 4.6%, respectively.

Figure 2 demonstrates the prevalence of different types of astigmatism among different age groups; the prevalence of against-the-rule astigmatism increased from 27.6% in 40-49 years old subjects to 55.2% in 70-80 years old individuals (OR=1.044, 95%CI, 1.034-1.054, P<0.001). However, with-the-rule astigmatism did not have a significant relationship with age (P=0.510).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of astigmatism in different age groups in the elderly population of Yazd district, Iran.

The prevalence of against-the-rule astigmatism was 34.1% and 37.6% in women and men, respectively (P=0.112). Yet, with-the- rule astigmatism was significantly higher in women (P=0.038); corresponding values were 15% and 11.7% in women and men, respectively. The prevalence of oblique astigmatism was also significantly higher in women than men (5.8% versus 3.3%, P=0.010). Regarding the relationships among different types of astigmatism, age and gender, multiple model findings were similar to the simple model.

Anisometropia

Anisometropia of 1 D or higher was observed in 11.9% (95%CI: 10.4-13.4%) of the study population. There was no significant relationship between anisometropia and gender (P=0.728), however the odds of being anisometropic increased by about 5% for each year of increasing age (P<0.001). The prevalence of anisometropia was significantly higher after the age of 59 compared to 40-49 year-old subjects (Table 2). There was no significant difference between urban and rural populations regarding the prevalence of anisometropia (P=0.196). The prevalence of anisometropia was significantly higher among illiterates as compared to other levels of literacy (Table 2). Anisometropia did not have a significant relationship with nuclear cataracts (P=0.168).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of different types of refractive errors in the Iranian population has already been studied in various surveys during the past decade.6,17-20 While most of these studies were related to student populations,17,19 refractive errors among the elderly have also been reported in Tehran and Mashhad surveys.6,20 Nevertheless, the latter two reports had limitations in addressing refractive errors in elderly population; they had lower sample sizes as compared to the current study and reported a high prevalence of hyperopia in the Iranian population which should be confirmed by further studies. This study evaluated individuals aged 40 to 80 years of age and in order to make a precise comparison with other reports,5,10,23,24,30 emmetropia was defined as SE from -0.5 to +0.5 D.

In contrast to other reports from Iran,6,18,20 the prevalence of myopia was higher than hyperopia in the current study with almost 36.5% of the study population being myopic. The prevalence of myopia among subjects older than 50 years was 23% and 27.2% in Tehran6 and Mashhad20 surveys, respectively. Their rates were lower as compared to the same age groups in our study; one point should be borne in mind that subjects with SE of -0.5 D were considered myopic in the two above-mentioned studies. In other words, although the cutpoints of defining myopia in Tehran6 and Mashhad20 studies were lower than ours, myopia was still more prevalent in the current study.

Prevalence of myopia more than -0.5 D in people aged 40 years or older in Myanmar3 (51%), Japan10 (41.8%), Singapore5 (35%) and India29 (34.6%) were higher than or equal to our study. Meanwhile, the prevalence of myopia was higher in the current study as compared to studies conducted in India24 (27%), Singapore23 (30.7%), Beaver Dam31 (26.2%), China32 (19.4%), Mongolia33 (17.2%) and Austrailia34 (17%). According to previous Iranian studies6,18,20, we did not expect a high prevalence of myopia in middle-aged or elderly subjects. However, not only was the prevalence of myopia higher as compared to previous Iranian studies6,18,20, but was also higher than many other surveys carried out in different parts of the world like China31, India24 and Singapore23 which are known places with a high prevalence of myopia. This is difficult to explain; nevertheless since race, gender, genes and environmental factors may affect myopia35,36, our finding could be due to racial and genetic differences among this particular group of Iranian population. We should consider the fact that Yazd population is more homogeneous in terms of genetic and racial characteristics than Tehran6 and Mashhad20.

The prevalence of hyperopia was rather low in our study, especially among 40-50 year-old subjects. The prevalence of hyperopia was 58.6% and 51.6% in Tehran6 and Mashhad20 studies, respectively. Findings of these two studies in terms of hyperopia were considerably different from our study despite the fact that the definition of hyperopia (SE of 0.5 D or higher) was similar to ours in Mashhad study. Although subjects with SE of 0.5 D were enrolled as hyperopic cases in the Tehran study6, the prevalence of hyperopia was so high that could not be justified by different definitions only. There are different studies worldwide such as the Blue Mountains37 (57%), Barbados38 (46.9%) and Beaver Dam31 (49%) in which the prevalence of hyperopia was considerably higher than our study. Considering the inverse relationship between hyperopia and myopia, it seems that the same reason for a high prevalence of myopia in our study has led to a low prevalence of hyperopia. In fact, since cycloplegic refraction is more valid than non- cycloplegic refraction in all age groups,39 a lower prevalence of hyperopia, especially as compared to Tehran6 study, can partly be explained by the use of non-cycloplegic refraction in our study.

Surprisingly, astigmatism was present in more than half of our study population. Astigmatism was observed in more than 60% and 70% of individuals aged 60-69 and 70-80 years, respectively. The prevalence of astigmatism was reported to be 37.5% in Mashhad20 study while the Shahroud40 study reported the prevalence of astigmatism to be high (49%). Rates of astigmatism in both of these two studies were lower than ours. The highest prevalence of astigmatism has been reported from Indonesia4 (77%) and Taiwan32 (74%) in subjects aged above 50 and 65 years, respectively; the lowest rate has been reported in subjects over 40 years of age in Myanmar3 (30.6%) and Blue Mountain37 (37%). One of the most important reasons for the higher prevalence of astigmatism in the current study as compared to previous Iranian studies is the dry and hot climate of Yazd. Dry weather in that region may have caused an increase in ophthalmic reactions resulting in eye rubbing giving rise to astigmatism. Shahroud, where the prevalence of astigmatism is also high, has a dry climate too. Our findings demonstrate that the prevalence of against-the-rule astigmatism is significantly higher than other forms of astigmatisms. The prevalence of against-the- rule astigmatism in Shahroud40, Singapore23, Bangladesh41 and Chinese residents of Taiwan32 was reported to be higher in elderly population. As will be further discussed, the prevalence of against-the-rule astigmatism is expected to be high in elderly populations while that of with- the-rule astigmatism is low.

We observed a prevalence of 11.9% for anisometropia in our study. The prevalence of anisometropia according to a cutpoint of 1 D or higher has been variable in middle- aged and elderly populations; the prevalence of anisometropia in the elderly population of Tehran27 and Mashhad20 was 30.0% and 10.7%, respectively. In Tehran27 study, subjects older than 65 years of age did not show a great difference with the same age group in the current study. The prevalence of anisometropia has been reported to range from 9.9% in Singaporeans23 aged 40 to 80 years to 35.3% in subjects aged 40 to 70 years in Myanmar28. Meanwhile, the prevalence of anisometropia in elderly Chinese residents of Singapore5, residents of Blue Mountain42 and Mongolia33 were 15.9%, 14.7% and 10.7%, respectively. Anisometropia had a medium to low prevalence and was not considered a serious visual issue in the elderly population of Yazd. However, since anisometropia may disturb binocular vision, its correction especially in elderly subjects who also have the problem of presbyopia is extremely important.

Our study revealed that, the prevalence of myopia had a significant relationship with female gender. Although most studies,20,43-46 unlike the current study, have found a higher prevalence of myopia in men, reports by Saw23, Wong5 and Brown47 also showed a higher prevalence of myopia among women.

Considering apparent differences in certain biometric components, especially axial length, between the two genders,44,48 we expected the prevalence of myopia to be higher in men due to greater axial length. Nevertheless, other causes could have been affected by gender in our study population changing the prevalence of myopia.

Our results showed that a higher prevalence of hyperopia could be observed with increasing age which has previously been addressed in various reports.6,37,38,49,50 Age-related decline in accommodation has already been proposed as a hypothesis in the etiology of hyperopia, nevertheless, a hyperopic shift was observed with age using cycloplegic refraction in Tehran study.51 Therefore, structural changes in the lens may be a plausible theory regarding this issue; this was first suggested by Danders and later confirmed by other surveys.52,53

Similar to other studies, the prevalence of astigmatism significantly increased with age in our study.40,54 Alterations in corneal curvature as a result of aging is an explanation for this finding. The observed decreased prevalence of with-the- rule and increased prevalence of against-the-rule astigmatism with age in our study have already been reported in other studies.26,55,56 There are various changes in the type of astigmatism with age. Read et al demonstrated that astigmatism varies during different stages of life.57 Age- related weakening of palpebral muscles and a reduction in palpebral pressure may decrease with-the-rule astigmatism and cause a shift toward against-the-rule astigmatism.58 With- the-rule astigmatism was more prevalent among women in our study; Mandel59 and Huynh60 also showed a higher rate of with-the-rule astigmatism in women. Difference in palpebral fissure slant between the two genders may be one of reasons for this finding.

To conclude, in contrast to previous studies in Iran, the prevalence of myopia was higher than hyperopia in the current survey. The prevalence of astigmatism was not only higher than myopia, but also greater than other Iranian studies. Taking all refractive errors into account, we observed that more than half of the elderly population had at least one type of refractive error. Regarding the fact that refractive errors are one of the most important causes of vision impairment worldwide, recognizing and correcting these errors can reduce ophthalmic problems.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:63–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith TS, Frick KD, Holden BA, Fricke TR, Naidoo KS. Potential lost productivity resulting from the global burden of uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:431–437. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.055673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A, Casson RJ, Newland HS, Muecke J, Landers J, Selva D, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in rural Myanmar: the Meiktila Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saw SM, Gazzard G, Koh D, Farook M, Widjaja D, Lee J, et al. Prevalence rates of refractive errors in Sumatra, Indonesia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3174–3180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong TY, Foster PJ, Hee J, Ng TP, Tielsch JM, Chew SJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in adult Chinese in Singapore. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2486–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Mohammad K. The age- and gender-specific prevalences of refractive errors in Tehran: the Tehran Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11:213–225. doi: 10.1080/09286580490514513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anera RG, Soler M, de la Cruz Cardona J, Salas C, Ortiz C. Prevalence of refractive errors in school-age children in Morocco. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37:191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He MG, Lin Z, Huang J, Lu Y, Wu CF, Xu JJ. Population-based survey of refractive error in school-aged children in Liwan District, Guangzhou. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2008;44:491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawada A, Tomidokoro A, Araie M, Iwase A, Yamamoto T. Refractive errors in an elderly Japanese population: the Tajimi study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan CW, Wong TY, Lavanya R, Wu RY, Zheng YF, Lin XY, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in Indians: the Singapore Indian Eye Study (SINDI). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3166–3173. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan CS, Chan YH, Wong TY, Gazzard G, Niti M, Ng TP, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors and ocular biometry parameters in an elderly Asian population: the Singapore Longitudinal Aging Study (SLAS). Eye (Lond) 2011;25:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ip JM, Saw SM, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Kifley A, Wang JJ, et al. Role of near work in myopia: findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2903–2910. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low W, Dirani M, Gazzard G, Chan YH, Zhou HJ, Selvaraj P, et al. Family history, near work, outdoor activity, and myopia in Singapore Chinese preschool children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1012–1016. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.173187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu B, Congdon N, Liu X, Choi K, Lam DS, Zhang M, et al. Associations between near work, outdoor activity, and myopia among adolescent students in rural China: the Xichang Pediatric Refractive Error Study report no. 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:769–775. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Jones LA, Zadnik K. Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children’s refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3633–3640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:287–292. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostadimoghaddam H, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Yekta A, Heravian J, Rezvan F, et al. Prevalence of the refractive errors by age and gender in Mashhad, Iran: the Mashhad eye study. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011;39:743–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yekta A, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Dehghani C, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Shiraz, Iran. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yekta AA, Fotouhi A, Khabazkhoob M, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. The prevalence of refractive errors and its determinants in the elderly population of Mashhad, Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16:198–203. doi: 10.1080/09286580902863049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katibeh M, Ziaei H, Pakravan M, Dehghan MH, Ramezani A, Amini H, et al. The Yazd Eye Study-a population-based survey of adults aged 40-80 years: rationale, study design and baseline population data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20:61–69. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2012.744844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pakravan M, Yazdani S, Javadi MA, Amini H, Behroozi Z, Ziaei H, et al. A Population-based Survey of the Prevalence and Types of Glaucoma in Central Iran: The Yazd Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saw SM, Chan YH, Wong WL, Shankar A, Sandar M, Aung T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in the Singapore Malay Eye Survey. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raju P, Ramesh SV, Arvind H, George R, Baskaran M, Paul PG, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in a rural South Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4268–4272. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heidary G, Ying GS, Maguire MG, Young TL. The association of astigmatism and spherical refractive error in a high myopia cohort. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:244–247. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000159361.17876.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano K, Nomura H, Iwano M, Ando F, Niino N, Shimokata H, et al. Relationship between astigmatism and aging in middle-aged and elderly Japanese. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Yekta A, Mohammad K, Fotouhi A. Prevalence and risk factors for anisometropia in the Tehran eye study, Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18:122–128. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2011.574333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu HM, Casson RJ, Newland HS, Muecke J, Selva D, Aung T. Anisometropia in an adult population in rural myanmar: the Meiktila Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:162–166. doi: 10.1080/09286580701843796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yekta A, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Dehghani C, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. The prevalence of anisometropia, amblyopia and strabismus in school children of Shiraz, Iran. Strabismus. 2010;18:104–110. doi: 10.3109/09273972.2010.502957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnaiah S, Srinivas M, Khanna RC, Rao GN. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in the South Indian adult population: The Andhra Pradesh Eye disease study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:17–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q, Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Refractive status in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:4344–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng CY, Hsu WM, Liu JH, Tsai SY, Chou P. Refractive errors in an elderly Chinese population in Taiwan: the Shihpai Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4630–4638. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wickremasinghe S, Foster PJ, Uranchimeg D, Lee PS, Devereux JG, Alsbirk PH, et al. Ocular biometry and refraction in Mongolian adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:776–783. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wensor M, McCarty CA, Taylor HR. Prevalence and risk factors of myopia in Victoria, Australia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:658–663. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McBrien NA, Young TL, Pang CP, Hammond C, Baird P, Saw SM, et al. Myopia: Recent Advances in Molecular Studies; Prevalence, Progression and Risk Factors; Emmetropization; Therapies; Optical Links; Peripheral Refraction; Sclera and Ocular Growth; Signalling Cascades; and Animal Models. Optom Vis Sci. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgan I, Rose K. How genetic is school myopia? Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:1–38. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attebo K, Ivers RQ, Mitchell P. Refractive errors in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1066–1072. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu SY, Nemesure B, Leske MC. Refractive errors in a black adult population: the Barbados Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2179–2184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fotouhi A, Morgan IG, Iribarren R, Khabazkhoob M, Hashemi H. Validity of noncycloplegic refraction in the assessment of refractive errors: the Tehran Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:380–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Yekta A, Jafarzadehpur E, Emamian MH, Shariati M, et al. High prevalence of astigmatism in the 40- to 64- old population of Shahroud, Iran. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bourne RR, Dineen BP, Ali SM, Noorul Huq DM, Johnson GJ. Prevalence of refractive error in Bangladeshi adults: results of the National Blindness and Low Vision Survey of Bangladesh. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guzowski M, Fraser-Bell S, Rochtchina E, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Asymmetric refraction in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:551–553. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eysteinsson T, Jonasson F, Arnarsson A, Sasaki H, Sasaki K. Relationships between ocular dimensions and adult stature among participants in the Reykjavik Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83:734–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warrier S, Wu HM, Newland HS, Muecke J, Selva D, Aung T, et al. Ocular biometry and determinants of refractive error in rural Myanmar: the Meiktila Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1591–1594. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.144477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mallen EA, Gammoh Y, Al-Bdour M, Sayegh FN. Refractive error and ocular biometry in Jordanian adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2005;25:302–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He M, Huang W, Li Y, Zheng Y, Yin Q, Foster PJ. Refractive error and biometry in older Chinese adults: the Liwan eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5130–5136. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu SY, Yoo YJ, Nemesure B, Hennis A, Leske MC. Nine-year refractive changes in the Barbados Eye Studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4032–4039. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shufelt C, Fraser-Bell S, Ying-Lai M, Torres M, Varma R. Refractive error, ocular biometry, and lens opalescence in an adult population: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4450–4460. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gudmundsdottir E, Arnarsson A, Jonasson F. Five-year refractive changes in an adult population: Reykjavik Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee KE, Klein BE, Klein R, Wong TY. Changes in refraction over 10 years in an adult population: the Beaver Dam Eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2566–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hashemi H, Iribarren R, Morgan IG, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K, Fotouhi A. Increased hyperopia with ageing based on cycloplegic refractions in adults: the Tehran Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:20–23. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.160465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donsers FC. On the anomalies of accommodation and refraction of the eye; with a preliminary essay on physiological dioptrics. London: The New Syndenham Society; 1864. pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hemenger RP, Garner LF, Ooi CS. Change with age of the refractive index gradient of the human ocular lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:703–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee KE, Klein BE, Klein R. Changes in refractive error over a 5-year interval in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1645–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Topuz H, Ozdemir M, Cinal A, Gumusalan Y. Age- related differences in normal corneal topography. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2004;35:298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gudmundsdottir E, Jonasson F, Jonsson V, Stefansson E, Sasaki H, Sasaki K. “With the rule” astigmatism is not the rule in the elderly. Reykjavik Eye Study: a population based study of refraction and visual acuity in citizens of Reykjavik 50 years and older. Iceland-Japan Co-Working Study Groups. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:642–646. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078006642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Read SA, Collins MJ, Carney LG. A review of astigmatism and its possible genesis. Clin Exp Optom. 2007;90:5–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2007.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Read SA, Collins MJ, Carney LG. The influence of eyelid morphology on normal corneal shape. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:112–119. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mandel Y, Stone RA, Zadok D. Parameters associated with the different astigmatism axis orientations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:723–730. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huynh SC, Kifley A, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Mitchell P. Astigmatism in 12-year-old Australian children: comparisons with a 6-year-old population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:73–82. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]