Abstract

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of keratoconus (KCN) and subclinical KCN among subjects with two or more diopters (D) of astigmatism, and to compare Pentacam parameters among these subjects.

Methods

One hundred and twenty eight eyes of 64 subjects with astigmatism ≥2D were included in the study. All subjects underwent a complete ophthalmic examination which included refraction, visual acuity measurement, slit lamp biomicroscopy, retinoscopy, fundus examination, conventional corneal topography and elevation-based topography with Pentacam. The diagnosis of KCN and subclinical KCN was made by observing clinical findings and topographic features; and confirmed by corneal thickness and elevation maps of Pentacam. Several parameters acquired from Pentacam were analyzed employing the Mann-Whitney U Test.

Results

Mean age of the study population was 29.9±9.8 (range 15-45) years which included 39 (60.9%) female and 25 (39.1%) male subjects. Maximum corneal power, index of vertical asymmetry, keratoconus index and elevation values were significantly higher and pachymetry was significantly thinner in eyes with clinical or subclinical KCN than normal astigmatic eyes (P< 0.05).

Conclusion

The current study showed that subjects with 2D or more of astigmatism who present to outpatient clinics should undergo corneal topography screening for early diagnosis of KCN even if visual acuity is not affected. Pentacam may provide more accurate information about anterior and posterior corneal anatomy especially in suspect eyes.

Keywords: Keratoconus, Subclinical Keratoconus, Pentacam, Scheimpflug, Astigmatism, Corneal Topography

INTRODUCTION

Keratoconus (KCN) is a chronic, bilateral, non-inflammatory disorder characterized by progressive steepening, thinning and apical scarring of the cornea. The annual incidence of KCN is 2 per 100,000 with a prevalence of 54.5 per 100,000 (approximately 1 per 2,000).1-3 KCN usually manifests as progressive myopia and irregular astigmatism, with unique slit lamp findings. The diagnosis of advanced KCN can be easily made because of its characteristic biomicroscopic and topographic findings, but identification of subclinical cases may be extremely challenging.1,4 Refractive surgery candidates should be examined meticulously since keratorefractive treatment may exacerbate the clinical progression of this ectasia.5,6

The diagnosis of subclinical KCN can be tenuous. The term “subclinical KCN” is used to state a premature form of the disease in which characteristic keratometric, retinoscopic or slit lamp findings are absent, but mild topographic changes are consistent with clinical KCN.7 Identification of subclinical KCN is challenging as diagnostic criteria should be determined.8 It is usually not easy to predict the natural course of the disease because corneal alterations start generally before a patient is referred to an ophthalmologist. During puberty, the cornea starts to get thinner and protrudes, causing irregular astigmatism. In the stationary phase of the disease, the condition may vary from mild irregular astigmatism to severe thinning.9,10 Several methods with different corneal topographers have been introduced to aid the diagnosis of KCN and subclinical KCN. The Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) is a state-of-the-art instrument that scans the anterior and posterior cornea with a rotating Scheimpflug camera. Repeatability and reproducibility of corneal thickness and posterior elevation measurements has been reported to be high.11,12 However, unlike the Orbscan topographer (Bausch & Lomb Inc., Rochester, NY, USA), it is not clear what comprises normal or abnormal posterior elevation of the cornea measured with this

The aim of the current study was to determine the prevalence of KCN and subclinical KCN in subjects with astigmatism of two diopters (2D) or greater using data from the Pentacam Scheimpflug tomographer.

METHODS

Consecutive subjects (aged 15 to 45 years) with 2D or greater of astigmatism, presenting to our ophthalmology outpatient clinic for routine check-ups were included in this cross-sectional study. All subjects underwent a complete ophthalmic examination that included visual acuity measurement with an ETDRS chart, slit lamp biomicroscopy, retinoscopy, fundus examination and corneal topography (TMS-4; Tomey, Erlangen, Germany). Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), retinoscopic, slit lamp biomicroscopic and funduscopic findings were recorded. Only subjects with no signs of other ocular pathology were included.

An eye was diagnosed as having KCN if there was a scissoring reflex on retinoscopy and central or paracentral steepening of the cornea on topography with at least 1 of the following slit lamp findings: stromal thinning, anterior bulging of cornea, Vogt striae, Fleischer ring, Descemet’s breaks, apical scars, and subepithelial fibrosis.14 An eye was diagnosed with subclinical KCN if it was the fellow eye of a patient with KCN or showed the following features: normal cornea by slit lamp biomicroscopy, normal keratometry, retinoscopy and ophthalmoscopy but inferior-superior asymmetry or bow-tie pattern with skewed radial axes detected on tangential maps. Subjects not fulfilling these criteria were classified in the normal astigmatic group.

A single experienced observer, who was masked to the patient diagnosis, performed all Pentacam measurements. Briefly, the subject was asked to place his/her chin on the chin rest and the forehead against the head rest. The subject was asked to open both eyes and look at the fixation target. The examiner aligned the joystick until the rotating Scheimpflug camera automatically captured 25 single images within 2 seconds for each eye. The measurements were checked under the quality specification window; only correct measurements were accepted (comment box reading ‘’OK’’). If the comment box was marked yellow or red, the examination was repeated. Maps with poor centration were repeated in order to provide a best-fit toric/ ellipsoid reference surface. Subjects with corneal surface irregularity were re-examined with Pentacam after using artificial tears for 2 weeks. From the Pentacam examination, flat (K1) and steep (K2) keratometric readings, maximum simulated keratometry (Kmax), corneal thickness at the thinnest point of the cornea (minimal pachymetry), index of surface variance (ISV), index of vertical asymmetry (IVA), KCN index (KI), anterior elevation (AE) and posterior elevation (PE) were recorded into an Excel worksheet.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The bootstrap method was applied to eliminate the correlation between eyes of the same subject by treating each subject as a cluster. For group comparisons of continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty eight eyes of 64 subjects were analyzed. Mean age was 29.9±9.8 (range, 15 to 45) years and the study population included 39 (60.9%) female and 25 (39.1%) male subjects.

Mean spherical and cylindrical refractive error was -0.63±1.92D, -2.36±1.79D respectively. Mean best-corrected visual acuity was 0.09±0.02 (0.0-0.16) logMAR. Pentacam measurements yielded mean K1, K2 and Kmax of 42.5±1.8D, 45.3±1.9D and 46.3±2.6D respectively. Mean minimal pachymetry value was 536±47 µm, mean ISV was 30.6±15.7, mean IVA was 0.21±0.19 and mean KI was 1.02±0.05. Mean AE and PE were 3.7±6.7 µm, 5.9±11.1 µm respectively.

From the entire study sample, 8 eyes (6.3%) were diagnosed with KCN and 10 eyes (7.8%) as subclinical KCN. Out of 9 patients with KCN and subclinical KCN, 6 were female and 3 were male; 3 patients had bilateral KCN, 4 patients had bilateral subclinical KCN and 2 patients had KCN in one eye and subclinical KCN in the fellow eye. Mean age was 32.1±7.3 years in patients with KCN, 29.1±5.2 years in patients with subclinical KCN and 29.0±9.8 years in astigmatic patients. There were no statistically significant differences in spherical and cylindrical refractive error among KCN, subclinical KCN and astigmatic eyes (P > 0.05, for all comparisons).

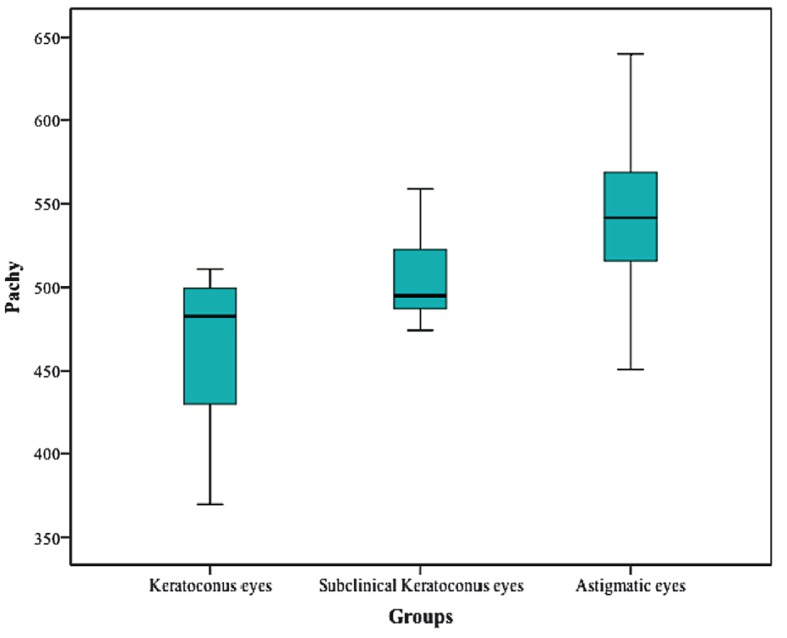

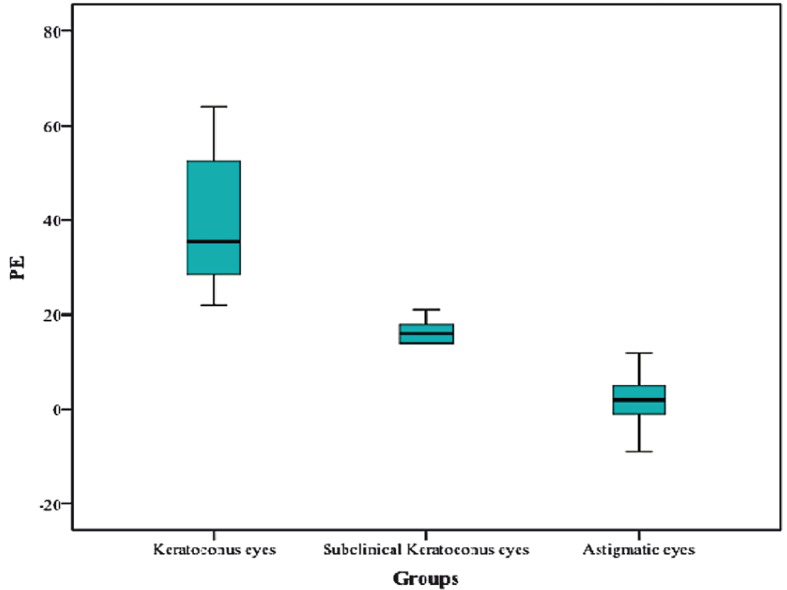

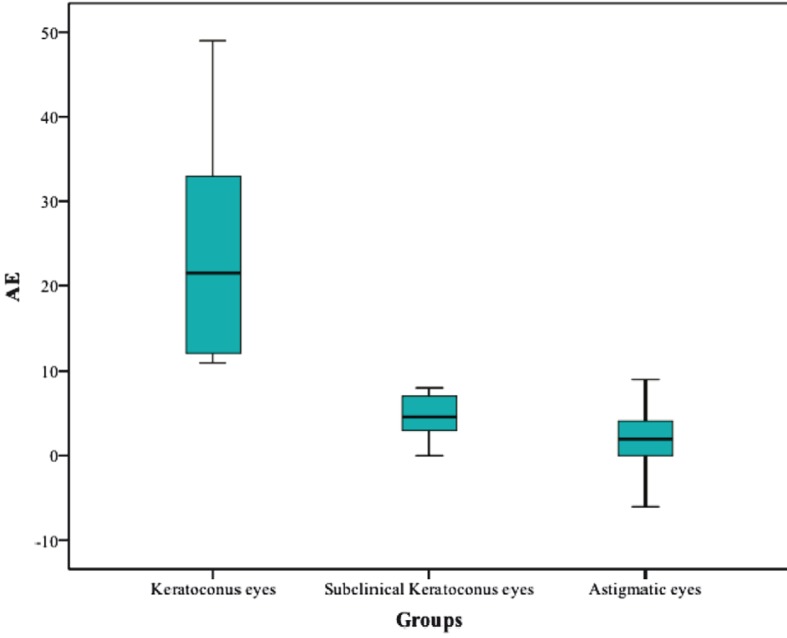

Table 1 details Pentacam parameters in the three study groups. There were statistically significant differences between KCN eyes and astigmatic eyes in all Pentacam parameters except for cylindrical refractive error (P<0.001). With the exception of K1, K2, Kmax, cylindrical error and ISV value, statistically significant differences were found in all parameters between subclinical KCN eyes and astigmatic eyes (P<0.05). Mean minimal pachymetry was 463±52 µm in KCN eyes, 505±27 µm in subclinical KCN eyes and 544±42 µm in astigmatic eyes (Fig. 1). Mean anterior elevation was 24.13±13.79 µm, 4.60±2.75 µm and 2.11±2.69 µm, respectively. Mean posterior elevation was 39.88±15.76 µm, 16.40±2.63 µm, 2.42±4.47 µm, respectively. The distributions of anterior and posterior corneal elevations are presented in figure 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Mean values for Pentacam parameters by study group

| Parameter | Mean±Standard Deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keratoconus | Subclinical Keratoconus | Astigmatism | P Value* | |

| K1 (D) | 47.00 ± 2.52 | 42.46 ± 1.19 | 42.24 ± 1.39 | 0.000 / 0.531 |

| K2 (D) | 49.51 ± 2.69 | 44.78 ± 1.23 | 45.07 ± 1.51 | 0.000 / 0.518 |

| Kmax (D) | 53.53 ± 3.85 | 45.55 ± 1.15 | 45.83 ± 1.64 | 0.000 / 0.621 |

| Cyl (D) | -2.50 ± 1.67 | -2.48 ± 1.54 | -2.34 ± 1.83 | 0.779 / 0.710 |

| Min Pachy (µm) | 463.13 ± 52.04 | 504.90 ± 27.15 | 544.24 ± 42.45 | 0.000 / 0.003 |

| ISV | 76.13 ± 25.62 | 27.60 ± 8.44 | 27.96 ± 8.45 | 0.000 / 0.853 |

| IVA | 0.83 ± 0.30 | 0.23 ± 0.06 | 0.17 ± 0.09 | 0.000 / 0.001 |

| KI | 1.18 ± 0.73 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.000 / 0.006 |

| AE (µm) | 24.13 ± 13.79 | 4.60 ± 2.75 | 2.11 ± 2.69 | 0.000 / 0.010 |

| PE (µm) | 39.88 ± 15.76 | 16.40 ± 2.63 | 2.42 ± 4.47 | 0.000 /0 .000 |

K1, flat keratometry; K2, steep keratometry; Kmax, maximum simulated keratometry; Cyl, cylindrical value

Min Pachy, corneal thickness at the thinnest point of the cornea; ISV, index of surface variance

IVA, index of vertical asymmetry; KI, keratoconus index; AE, anterior elevation; PE, posterior elevation

D, diopters

Keratoconus versus astigmatic eyes / subclinical keratoconus versus astigmatic eyes

Figure 1.

Distribution of minimal pachymetry (Pachy) in eyes with keratoconus, subclinical keratoconus and astigmatism.

Figure 2.

Distribution of anterior elevation (AE) in eyes with keratoconus, subclinical keratoconus and astigmatism.

Figure 3.

Distribution of posterior elevation (PE) in eyes with keratoconus, subclinical keratoconus and astigmatism.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of KCN among refractive surgery candidates has been reported to vary from 0.9% to 8.1%.15,16 Corneal pachymetry in keratoconic corneas has been studied with various instruments17 and many studies have compared the reproducibility and reliability of instruments with different operating principles.15,18

The Pentacam, which is based on the Scheimpflug principle, measures 138,000 elevation points. This technique can be used as a screening test for detecting KCN since it works independent of axis, orientation and position of the eye. It has been shown that elevation- based topography systems are more accurate than Placido-based devices in differentiating normal eyes from early KCN.16

It is not difficult to detect clinically advanced KCN on the basis of slit lamp biomicroscopic findings. However, it can be problematic to distinguish between KCN suspects and normal eyes only with topographic criteria. There are no definite or universally accepted diagnostic criteria for defining KCN suspects. For instance, anterior corneal topography may present increased asymmetry such as localized steepening of the inferior cornea without other characteristic criteria for both keratoconus and contact lens-induced corneal warpage. There may be asymmetry between the right and the left eyes, i.e. reduced enantiomorphism. Subjects with steep keratometric values and progressive astigmatism may also have subclinical KCN.17

In patients seeking refractive surgery, a high incidence of ‘forme fruste’ KCN and ‘KCN suspect’ has been reported in early studies. Some investigators stated that this overdiagnosis was related to the sagittal-based curvature measurements by Placido-based topography systems.19,20 Many patients, who had previously been labelled as keratoconic, were found to have a displaced corneal apex. It has been pointed out that these eyes demonstrate elevated I-S ratio, normal pachymetry, orthogonal astigmatism and stable refractions with no other clinical or topographical feature of KCN.21

Lim et al22 found that more than one third of subjects with unilateral KCN developed manifest KCN in the other eye over 8 years. These authors reported that mean values of maximum posterior elevation and irregularity were significantly higher in KCN and KCN-suspects than control eyes.

Recently, Ucakhan et al15 investigated several Pentacam parameters in subclinical KCN, KCN and normal eyes. They found that the Scheimpflug system could differentiate between ectatic and normal eyes. In this study, the optimum cut-off point for posterior elevation was found to be 26.5 µm (97.7 % sensitivity and 81.0 % specificity). Logistic regression analysis indicated that a model combining corneal power, thickness and elevation data produced the best predictive accuracy in KCN and subclinical KCN.15

In a study by Mihaltz et al23 ROC curve analysis indicated that posterior elevation was the most important criterion in the diagnosis of KCN. A threshold value of 15.5 µm had sensitivity of 95.1% and specificity of 94.3% for differentiating normal eyes from KCN. These authors found lower pachymetry readings in subclinical, early and moderate KCN; however, they did not find significant differences in these parameters between subclinical KCN and normal eyes.23

Pinero et al24 investigated corneal volume, pachymetry and the correlation between anterior and posterior corneal shape in normal and KCN eyes. They found lower pachymetry readings in subclinical and clinical KCN, but found no remarkable differences in these measurements between subclinical KCN eyes and normal eyes.24

Based on topographic maps from the Pentacam, Vejarano25 stated that KCN should be highly suspected in eyes with anterior elevation greater than 15 µm and posterior elevation greater than 20 µm using the best fit toric ellipsoid, corneal thickness less than 500 µm, and keratometric power greater than 47D on the tangential map when all are at the same corresponding points. Subjects who had anterior elevation between 12 and 15 µm, posterior elevation between 15 and 20 µm with a corresponding location of thinnest pachymetry point less than 500 µm were diagnosed as KCN suspects.25

When screening patients for ectasia using the Pentacam, higher sensitivity and specificity have been achieved by combining pachymetric graphs and indices, and the enhanced elevation maps provided by the Belin/Ambrosio Enhanced Ectasia Display.26 In our study, the mean values were compatible with the results of other studies and well correlated with the Belin/Ambrosio Enhanced Ectasia Display.

In our study, 14.1% of patients attending the general ophthalmology outpatient clinic with astigmatism of 2D or greater had some degree of KCN (6.3% of eyes had KCN and 7.8% had subclinical KCN). When we compare this prevalence with other studies, it is obvious that higher prevalence rates for KCN will be found as cylindrical power increases. Since this study is limited by sample size, our results may not reflect the actual prevalence of KCN in the population with ≥2D of astigmatism. However, our study showed that various parameters acquired from Pentacam measurements can help discriminate eyes with varying degrees of KCN from normal eyes. The analysis of these measurements is important in differentiating eyes with subclinical KCN from normal eyes. Sometimes analyzing curvature maps separately may mislead ophthalmologists in the diagnosis of KCN. It has been emphasized that anterior elevation, posterior elevation and thinnest pachymetry values appear to be the most crucial components in the diagnosis and follow up of KCN patients.8 While assessing KCN with Pentacam, tangential curvature maps should always be combined with corneal thickness and elevation maps.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of KCN is an increasingly important clinical issue as many methods are being developed such as cross- linking to halt the progression of this ectatic disease. The incidence of KCN is higher than estimated because of the increasing use of imaging systems such as the Pentacam. Since keratoconus induces irregular astigmatism and myopia, subjects with astigmatism of 2D or greater attending to outpatient clinics should be screened with corneal topography for early diagnosis even if their visual acuity is not affected. We think that Pentacam provides more accurate diagnosis than conventional corneal topography systems especially in keratoconus suspect eyes.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:297–319. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krachmer JH, Feder RS, Belin MW. Keratoconus and related noninflammatory corneal thinning disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:293–322. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy RH, Bourne WM, Dyer JA. A 48-year clinical and epidemiologic study of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon TT, Edrington TB, Szczotka-Flynn L, Olafsson HE, Davis LJ, Schechtman KB. Longitudinal changes in corneal curvature in keratoconus. Cornea. 2006;25:296–305. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000178728.57435.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciolino JB, Belin MW. Changes in the posterior cornea after laser in situ keratomileusis and photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1426–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein SR, Epstein RJ, Randleman B, Stulting RD. Corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis in subjects without apparent preoperative risk factors. Cornea. 2006;25:388–403. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000222479.68242.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Rabinowitz YS, Rasheed K, Yang H. Longitudinal study of the normal eyes in unilateral keratoconus subjects. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Sanctis U, Loiacono C, Richiardi L, Turco D, Mutani B, Grignolo FM. Sensitivity and specificity of posterior corneal elevation measured by pentacam in discriminating keratoconus/subclinical keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1534–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmund C. Corneal topography and elasticity in normal and keratoconus eyes. A methodological study concerning the pathogenesis of keratoconus. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1989;193:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ertan A, Muftuoglu O. Keratoconus clinical findings according to different age and gender groups. Cornea. 2008;27:1109–1113. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31817f815a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Sanctis U, Missolungi A, Mutani B, Richiardi L, Grignolo FM. Reproducibility and repeatability of central corneal thickness measurement in keratoconus using the rotating Scheimpflug camera and ultrasound pachymetry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D, Lam AK. Intrasession and intersession repeatability of the Pentacam system on posterior corneal assessment in the normal human eye. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quisling S, Sjoberg S, Zimmerman B, Goins K, Sutphin J. Comparison of Pentacam and Orbscan IIz on posterior curvature topography measurement in keratoconus eyes. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1629–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kymes SM, Walline JJ, Zadnik K, Gordon MO. Quality of life in keratoconus; the Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uçakhan ÖÖ, Cetinkor V, Özkan M, Kanpolat A. Evaluation of Scheimpflug imaging parameters in subclinical keratoconus, keratoconus, and normal eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37:1116–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belin MW, Khachikian SS. An introduction to understanding elevation-based topography: how elevation data are displayed - a review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37:14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gherghel D, Hosking SL, Mantry S, Banerjee S, Naroo SA, Shah S. Corneal pachymetry in normal and keratoconus eyes: Orbscan II versus ultrasound. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:1272–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barkana Y, Gerber Y, Elbaz U, Schwartz S, Ken-Dror G, Avni I, et al. Central corneal thickness measurement with the Pentacam Scheimpflug system, optical low-coherence reflectometry pachymeter, and ultra- sound pachymetry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:1729–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson SE, Klyce SD. Screening for corneal topographic abnormalities before refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGhee CNJ, Weed KH. Computerized videokeratography in clinical practice. In: McGhee CNJ, Taylor HR, Gartry DS, et al., editors. Excimer Lasers in Ophthalmology: Principles and Practice. London: Martin Dunitz Ltc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belin MW, Khachikian SS. New devices and clinical implications for measuring corneal thickness. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:729–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim L, Wei RH, Chan WK, Tan DT. Evaluations of keratoconus in Asians: role of Orbscan II and Tomey TMS-2 corneal topography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miháltz K, Kovács I, Takács A, Nagy ZZ. Evaluation of keratometric, pachymetric, and elevation parameters of keratoconus corneas with pentacam. Cornea. 2009;28:976–980. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31819e34de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piñero DP, Alió JL, Alesón A, Escaf M, Miranda M. Pentacam posterior and anterior corneal aberrations in normal and keratoconus eyes. Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92:297–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2009.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felipe Vejarano L. Obtaining Essential Performance with the Pentacam System for Corneal Surgery. Highlights of Ophthalmology: Jaypee-Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc. 2010;38:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belin MW, Khachikian SS, Ambrosio R, Salomão M. Keratoconus / Ectasia Detection with the Oculus Pentacam: Belin / Ambrósio Enhanced Ectasia Display. Highlights of Ophthalmology. 2007;35:5–12. [Google Scholar]