Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR) in an elderly patient.

Case Report

A 74-year-old Caucasian woman, with a 20-year history of a stable choroidal nevus in her right eye, was referred for evaluation of two small hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) affecting the temporal peripheral fundus of the same eye. Nine months later, the lesions became larger and indocyanine green angiography revealed polypoidal choroidal vascular changes corresponding to the location of the ophthalmoscopically visible PEDs. Despite one session of verteporfin photodynamic therapy, the lesions continued to enlarge eventually resulting in the development of a large hemorrhagic PED, which failed to respond to two subsequent injections of intravitreal bevacizumab. The final ophthalmoscopic appearance of the large hemorrhagic PED was typical of PEHCR.

Conclusion

This case suggests that polypoidal choroidal vascular changes similar to that seen in our patient may underlie the development of PEHCR in some cases.

Keywords: Eccentric Disciform Degeneration, Extramacular Disciform Degeneration, Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy, Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorio- retinopathy (PEHCR), also referred to as eccentric disciform degeneration, extramacular disciform degeneration and peripheral age- related retinal degeneration, is a degenerative condition affecting the peripheral fundus of elderly patients.1 PEHCR manifests with hemorrhagic and exudative alterations affecting the neurosensory retina or retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) including serous or hemorrhagic RPE detachment (RPED), subretinal hemorrhage, lipid exudation and exudative retinal detachment (RD).2,3 Similarities between the clinical manifestations of PEHCR with those of exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) have led some investigators to speculate a neovascular origin similar to exudative AMD for PEHCR.1,3 Recently, other investigators have shown similarities between the vascular characteristics of PEHCR and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV).4,5 In this report, we document the evolution of PEHCR in a 74-year-old woman who, on indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), was found to have choroidal vascular alterations resembling PCV in the affected area.

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old Caucasian woman, with a history of a stable choroidal nevus in her right eye for 20 years, was referred to a retina specialist for evaluation of a newly detected focus of hemorrhage affecting the temporal peripheral fundus of the same eye inferior to the choroidal nevus. The hemorrhage persisted despite an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab and the patient was referred to us for further management. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.

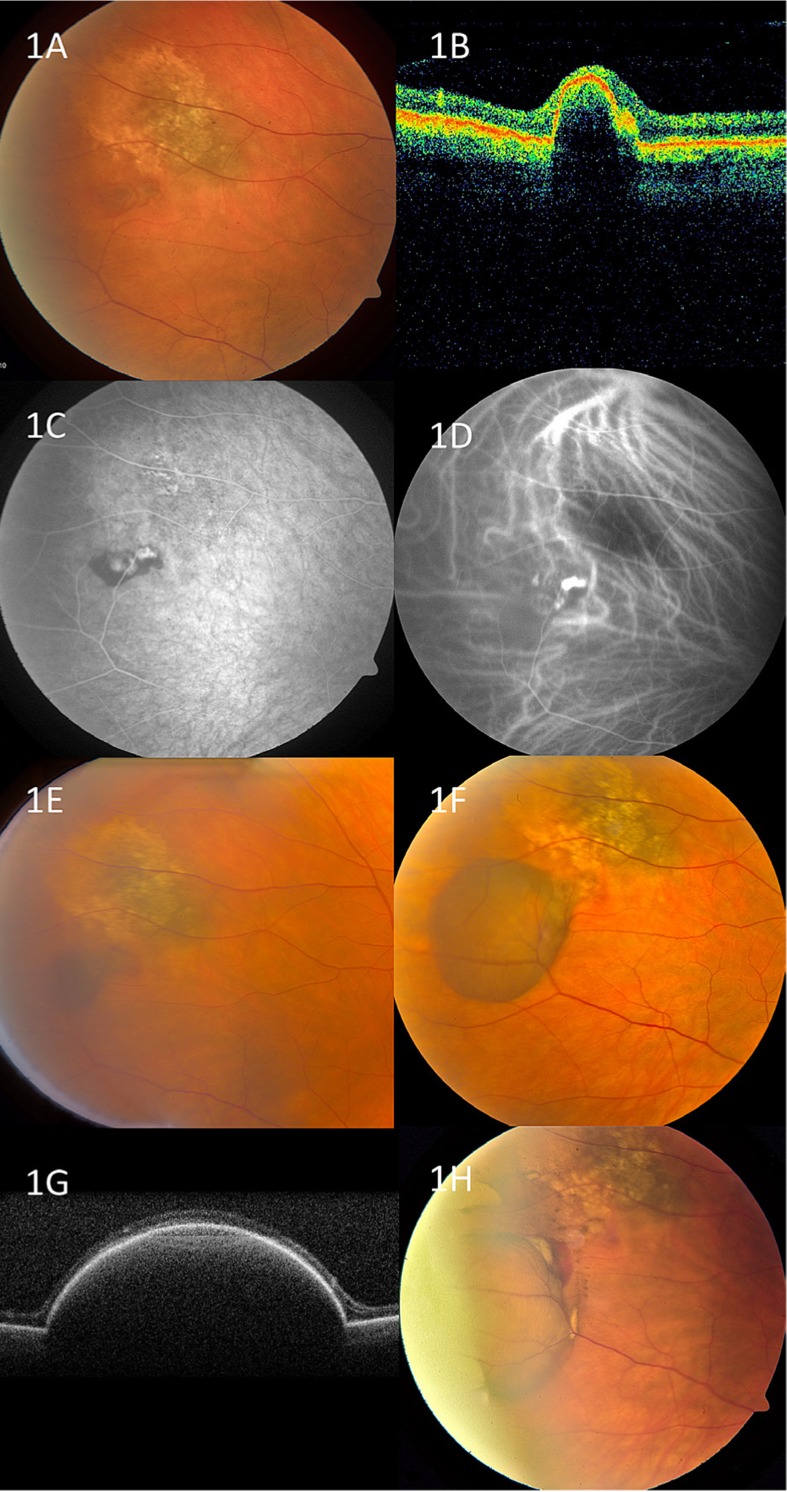

On initial evaluation she had corrected visual acuity of 20/20 in both eyes and intraocular pressures were 20 and 18 mmHg in the right and left eyes, respectively. Anterior segment examination of both eyes showed mild nuclear sclerosis. Fundus of the left eye was unremarkable except for mild peripheral RPE atrophy and no evidence of AMD. On funduscopy of the right eye, a pigmented choroidal nevus measuring 6 by 4 millimeters in basal dimensions and with overlying drusen was noted at the equator along the 10 o’clock meridian. Inferior to the nevus and separate from it, two nearly confluent hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachments (PED) were noticeable without any subretinal fluid or lipid exudation (Fig. 1A). There was no evidence of AMD.

Figure 1.

Gradual enlargement of peripheral hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachment (PED) in the right eye of a 74-year-old woman. A. Color fundus photograph shows a pigmented choroidal nevus with overlying drusen and two small hemorrhagic PEDs below the nevus. B. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows a small PED. C. Fluorescein angiography shows focal blockage of underlying choroidal fluorescence and two areas of hyperfluorescence corresponding to the location of the ophthalmoscopically visible PEDs. D. Indocyanine green angiography reveals the presence of polypoidal choroidal vessels corresponding to the location of the PEDs. E. Fundus photograph 11 months after initial evaluation and two months after standard photodynamic therapy. F. Four months later the hemorrhagic PED is significantly larger. G. OCT shows large PED with optically dense material inside. H. Four months later and after two monthly injections of intravitreal bevacizumab, the PED is larger and contains old blood. Note the presence of mild fresh and old subretinal hemorrhage at the superior and posterior margin of the PED.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed the presence of PED (Fig. 1B). Fluorescein angiography (FA) showed 2 focal areas of hyperfluorescence and leakage corresponding to the location of the PEDs (Fig. 1C). Due to the small size and peripheral location of the PEDs, observation was suggested.

Nine months later the hemorrhagic lesions were slightly larger with mild adjacent subretinal hemorrhage. ICGA revealed one large and several smaller polypoidal choroidal vessels corresponding to the location of the PEDs (Fig. 1D). After informing the patient of available treatment options, including continued observation, intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents, focal laser photocoagulation, or photodynamic therapy (PDT), one session of standard PDT with verteporfin was performed. Two months later, the sub-RPE and subretinal hemorrhage was stable in size but slightly darker in color (Fig. 1E). Repeat FA did not show any foci of leakage. On the next evaluation, three months later, the hemorrhagic lesion was larger in size but the patient continued to remain asymptomatic. Three weeks later, the patient experienced sudden onset of floaters and funduscopy showed a significant increase in the size of hemorrhagic PED (Fig. 1F), which measured 2.7 mm in thickness on B-scan ultrasonography. OCT revealed a large confluent PED with optically dense content (Fig. 1G). The patient received two monthly injections of intravitreal bevacizumab and on follow- up, three months later, the hemorrhagic PED was somewhat larger but the blood inside it had acquired a khaki color suggestive of old blood and lack of recent hemorrhage (Fig. 1H). Small foci of old subretinal hemorrhage were visible at the superior and nasal margins of the PED.

DISCUSSION

This case demonstrated the gradual enlargement and coalescence of small peripheral hemorrhagic PEDs into a large hemorrhagic PED in the eye of an elderly woman over the course of one and a half years. ICGA revealed peripheral choroidal vascular alterations resembling PCV and corresponding to the location of the PEDs. The final ophthalmoscopic appearance of a large hemorrhagic PED affecting the peripheral fundus closely resembles that of PEHCR suggesting that peripheral choroidal vascular alterations similar to PCV may underlie the development of PEHCR in some cases. The similarities between funduscopic features (serous and hemorrhagic PED, subretinal hemorrhage, lipid exudation) and the natural course (remitting-relapsing course with recurrent hemorrhagic episodes) of PCV and PEHCR support the hypothesis that these two conditions may indeed be the result of a similar underlying vascular lesion.6,7 This notion is supported by two recently published articles, which have shown the presence of peripheral polyp-like vascular changes in eyes with PEHCR.4,5 Similar to our case, the patients included in both of these studies were white and elderly and the lesions were more common in the temporal fundus.4,5

On the other hand, except in rare cases, PCV affects the peripapillary and macular regions whereas PEHCR is a disease of the peripheral (equatorial) fundus.8,9 Patients with PEHCR (mean age of 80 years) are also older than patients with PCV (mean age of 60 years). Moreover, to our knowledge, studies have not shown a higher rate of posterior PCV in eyes with PEHCR (or vice versa), denoting that despite the possibility of having a similar underlying vascular pathology, PCV and PEHCR can be separate entities and not just different clinical manifestations of the same disease entity.

It is our belief that the choroidal vascuopathy seen in our case was unrelated to the adjacent choroidal nevus. Although choroidal neovascular membranes are known to rarely develop in association with choroidal nevi, these membranes are usually of the classic type and develop directly over posteriorly located nevi.10 These features are to be contrasted with our case in which the choroidal vasculopathy was polypoidal and located outside a peripherally located nevus. Moreover, the development of a large hemorrhagic PED in our case was unlike the clinical presentation of choroidal neovascular membranes associated with choroidal nevi, which generally manifest as small focal areas of shallow serous subretinal fluid and subretinal hemorrhage usually with lipid exudation.10

In summary, we report an elderly woman with evolving PEHCR and polypoidal choroidal vascular alterations noted on ICGA in the area of involvement. These findings suggest that polypoidal choroidal vascular changes similar to that described in idiopathic PCV may be responsible for development of PEHCR.

Acknowledgments

Support provided by a donation from Michael Bruce, and Ellen Ratner, New York, NY (JAS, CLS), Mellon Charitable Giving from the Martha W. Rogers Charitable Trust, Philadelphia, PA (CLS), and the Eye Tumor Research Foundation, Philadelphia, PA (CLS, JAS).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Annesley WH. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:321–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields CL, Salazar PF, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy simulating choroidal melanoma in 173 eyes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantel I, Uffer S, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: a clinical, angiographic, and histologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:932–938. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantel I, Schalenbourg A, Zografos L. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and hemodynamic modifications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:910–922. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman DR, Freund KB, McCannel CA, Sarraf D. Peripheral polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy as a cause of peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy: A report of 10 eyes. Retina. 2013;33:48–55. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31825df12a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YT, Kang SW, Lee JH, Chung SE. Peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy in Korean patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54:227–231. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciardella AP, Donsoff IM, Huang SJ, Costa DL, Yannuzzi LA. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yannuzzi LA, Nogueira FB, Spaide RF, Guyer DR, Orlock DA, Colombero D, et al. Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: a peripheral lesion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:382–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karagiannis DA, Soublis V, Kandarakis A. A case of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Periphery is equally important for such patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:315–317. doi: 10.2147/cia.s6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zografos L, Mantel I, Schalenbourg A. Subretinal choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal nevus. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2004;14:123–131. doi: 10.1177/112067210401400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]