Abstract

Thrombus formation in an atherosclerotic or aneurysmal descending thoracic aorta is a well-described, frequently encountered vascular condition. In comparison, thrombus formation in a normal-appearing descending thoracic aorta is reported far less often.

We describe the case of a 46-year-old woman who had splenic and renal infarctions secondary to embolic showers from a large, mobile thrombus in a morphologically normal proximal descending thoracic aorta. After the patient underwent anticoagulation, stent-grafting, and surgical bypass to correct an arterial blockage caused by the stent-graft, she resumed a relatively normal life. In contrast with other cases of a thrombotic but normal-appearing descending thoracic aorta, this patient had no known malignancy or systemic coagulative disorders; her sole risk factor was chronic smoking. We discuss our patient's case and review the relevant medical literature, focusing on the effect of smoking on coagulation physiology.

Key words: Anticoagulants/therapeutic use; aorta, thoracic/pathology/radiography/surgery; aortic diseases/diagnosis/etiology/therapy; diagnostic imaging; embolism/diagnosis/etiology; endothelium, vascular/physiology; risk factors; smoking/physiopathology; thrombosis/diagnosis/etiology/surgery/therapy

We report the case of a woman who had mural thrombus in a normal-appearing descending thoracic aorta (NADTA). Her only risk factor was chronic smoking. Smoking can cause immediate microscopic changes in the vascular endothelium that can be as prothrombotic as an aneurysm or atherosclerotic plaque. We discuss our patient's case and review the relevant medical literature.

Case Report

In February 2011, a 46-year-old woman emergently presented with a 2-day history of dull, aching abdominal pain in the left upper quadrant. A similar episode had occurred 2 weeks earlier. The constant pain was associated with nausea and nonbloody, nonbilious vomiting. The patient's medical history included renal calculi, migraine headaches, tonsillectomy, tubal ligation, and hysterectomy. She had a 30-pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

The patient was not in acute distress. Physical examination revealed a normal blood pressure, pulse rate, and temperature. Cardiac auscultation yielded normal sounds without rubs, gallops, or murmurs. Both lungs were clear to auscultation. The left upper quadrant of the abdomen was tender to palpation, but no mass was discernible. Hypoactive bowel sounds were heard in all 4 quadrants, with no rebound tenderness, guarding, or rigidity. All peripheral pulses were palpable. No clubbing, cyanosis, or edema of the extremities was noted. No splinter hemorrhages or Janeway lesions were detected. The patient's laboratory values were all within normal ranges.

An electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with no ST-segment or T-wave changes. Computed tomograms (CTs) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ill-defined, wedge-shaped, hypoattenuating lesion in the spleen and several similar lesions in both kidneys. In the liver were 2 hypoattenuating lesions (length, 22 and 32 mm, respectively). There was no ductal dilation in the liver or pancreas. No abdominal aortic aneurysm was found.

Magnetic resonance images (MRI) of the abdomen showed 2 hepatic lesions, congruent with the CT findings. Revealed in addition were a moderate-sized infarction in the spleen and a few small infarctions in both kidneys; the most prominent of these was in the anterior aspect of the middle pole of the left kidney.

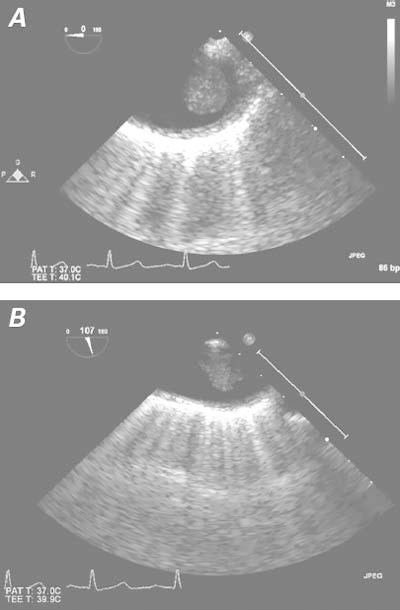

Multiple thrombotic emboli were causing the minor organ infarctions. Because 85% of emboli are cardiac in origin,1 we performed transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Examination of the left ventricle and the atria yielded no thrombi or valvular abnormalities. Chamber size, thickness, and function were all normal, as was left ventricular ejection fraction. However, a pedunculated, mobile, 1.3 × 1-cm mass was seen in the upper descending thoracic aorta, with no atherosclerotic plaque or aneurysmal dilation at the insertion base of the thrombus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Transesophageal echocardiograms in A) short-axis and B) long-axis views show a mobile thrombus in the upper descending thoracic aorta and no substantial atherosclerotic disease in the aortic wall.

The large thrombus in the NADTA prompted testing for coagulation disorders; the results showed no thrombophilia and nothing unusual in the patient's coagulation profile. Her partial thromboplastin time was 35 sec, her international normalized ratio (INR) was 0.94, and her prothrombin time was 10.1 sec. The patient was not deficient in protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III. Evaluation for anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant were negative. The homocysteine level was 8.6 μmol/L (normal range, <10.4 μmol/L), and the fibrinogen level was within normal limits. A test for antinuclear antibodies was negative. A search for prothrombin G20210A, a mutation in the prothrombin gene, was also negative. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase was positive in only one allele. The serum vitamin B12 and folic acid levels were normal.

The patient was started on a heparin drip and underwent thoracic aortic endografting as well as left carotid artery–subclavian artery bypass to correct a blockage of the left subclavian artery by the stent-graft. She recovered fairly well. Full anticoagulant therapy was resumed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital after 2 weeks with a prescription for warfarin. When the patient's incision was checked, she reported paresthesia throughout her left arm. Examination revealed tenderness in the left fingertips, some motor-strength deficits in the arm, a weak left radial pulse, and a positive bruit in the region of the left subclavian artery. Computed tomograms showed occlusion of the bypass graft. As of the 3rd postoperative month, the patient's symptoms had partially resolved, and she declined further surgery. She reported having quit smoking after the incident and returning to a relatively normal life with little activity restriction. She was lost to follow-up thereafter.

Discussion

Arterial thromboembolism has a substantially negative impact on morbidity and mortality rates. It is challenging to detect early and to treat, because most cases are found only when distal embolization causes organ ischemia and injury.2 Pieces of thrombus break off and migrate to the peripheral, visceral, and cerebral vasculature. The prevalence of arterial thromboembolism is unknown: most thrombi do not cause significant hemodynamic changes until they embolize, and even then they can migrate in clinical silence—for example, to regions with good collateral circulation.3 Approximately 85% of all arterial thrombi arise from cardiac causes, such as atrial fibrillation, valvular abnormalities, and myocardial infarction.1,2,4 Perhaps 5% of thrombi are found in the aorta, usually in the presence of atherosclerosis or aneurysm.4,5 In the aorta, thrombus typically forms in the isthmus—the region between the left subclavian artery and the first intercostal branch.6,7 The aortic isthmus is an intrinsically weak, injury-prone area, which perhaps explains why fibrin clots form in the isthmus.8

The classic Virchow's triad suggests 3 conditions that promote a prothrombotic state: hypercoagulability, stasis of blood flow, and endothelial injury. Therefore, when the aortic wall is injured (as in the development of atherosclerosis) or when blood flow becomes relatively stagnant (as in aneurysmal areas), thrombus formation becomes more likely. In the presence of a thrombotic NADTA, the causes are often more systemic. Typically, patients have hypercoagulable conditions such as malignancies, autoimmune disorders, and factor deficiencies.9–12 In rare cases, angiosarcoma of the aortic wall serves as the nidus for thrombus formation; therefore, aortic wall malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients who have evidence of aortic thrombosis.2 Caution is in order when qualifying the aorta as normal-appearing, because patients with thrombotic NADTA can have typical cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and smoking.3 Tissue biopsy of the aortic wall can confirm whether patients with a thrombotic NADTA have atheroma or atheroma-like histology. During our literature search, we found that not every case of thrombotic NADTA prompted a tissue biopsy; and most of the “normal” aortas were diagnosed with use of TEE, which enables insight into luminal patency but not necessarily the ultrafine structures of the wall. Many Korean War casualties who died of noncardiac events had vascular atherosclerosis13; in another report, no aortic sample was normal.14 We did not obtain a tissue specimen from the aorta of our patient. We presume that a biopsy specimen would have shown histologic changes in the aortic wall and would have served as visual proof of the damage that her cigarette smoking caused to the aortic wall.

Our patient's case is notable because, unlike patients in previous reports, she had no known systemic hypercoagulable disorder. Her only risk factor was a 30-pack-year history of smoking. Smoking causes endothelial damage and impairs the release of nitric oxide, a substance important for inhibiting platelet aggregation, smooth-muscle-cell proliferation, and monocyte adhesion.15 In addition, smoking increases blood viscosity via red blood cell aggregation and elevations in fibrinogen levels.16 The negative effects of smoking can be immediate: even brief exposure to tobacco smoke can make the fibrin ultrastructure more netlike, a condition that has been called “the sticky fibrin phenomenon.”17

Particularly in women, smoking has diminished the positive effect of estrogen on lipid profiles.18,19 However, estrogen's cardioprotective property cannot be presumed. In many patients with a thrombotic NADTA who used hormone replacement therapy, estrogen created a prothrombotic environment by decreasing antithrombin III and factor VII levels.20 Oral contraceptive agents and hepatic disease have predisposed patients to vascular intimal hyperplasia with or without thrombosis.21,22 Estrogen seems to play a substantial overall role in the natural history of thrombus in NADTA, because most cases have involved women of perimenopausal age who had dramatic fluctuations in estrogen level. Future study can help to identify individuals who are at high risk of developing aortic disease and who might benefit from routine screening.

There are no standardized guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of thrombotic NADTA. Nevertheless, TEE has proved to be effective in confirming and locating the thrombus, although sometimes underestimating its size.23 When used with high-frequency probes, TEE yields good image resolution, especially in characterizing the macroscopic appearance of the aortic wall and the implantation base of the mural thrombus, which is crucial to surgical planning.3 The TEE readings correlate well with operative findings.24 Another advantage of TEE is that of real-time imaging to detect the mobility of the thrombus, a characteristic of embolism and recurrence.1 Of other less invasive methods, CT is less sensitive than TEE,25,26 and MRI yields more false-positive results secondary to circulatory turbulence.23 Aortography is invasive, can cause thrombus migration, and yields images of comparatively poor quality.3 However, even when high-frequency probes are used, TEE lacks the resolution power to detect microscopic changes in the aortic wall. In addition, TEE cannot capture images of the abdominal aorta; CT or MRI is necessary to define the embolic source.24 For these reasons, intravascular ultrasonography might one day become the preferred diagnostic method.

Heparin has been preferred as initial therapy for thrombotic NADTA.2,3 If the thrombus has not responded after 2 weeks of heparin therapy, surgery might be appropriate. Surgical candidates include patients who are young and have a low risk of perioperative complications, those in whom conservative treatment has failed, and those who have a highly mobile thrombus and a consequently high embolic risk.1,3,4,7,24 Treatment options include thrombectomy, segmental aortic resection,2 thromboaspiration,27 and endoluminal stent-grafts.7 No approach is clearly superior. Endoluminal stent-grafting, the least invasive option, carries the risk of distal embolization through wire manipulation and stent deployment.2 Some clinicians prefer stent-grafting for reestablishing vascular patency and excluding the thrombus insertion site, thus minimizing further fibrin and platelet deposition.28–33

Independent of surgical treatment, long-term anticoagulation is recommended. There is no consensus on its duration, which can range from the time of complete resolution of the thrombus to lifelong.2 Choukroun and colleagues3 suggested an INR goal of 2.5 to 3.5. Heparin, vitamin K antagonists, and aspirin are used most often.2 Patients with a thrombotic NADTA can experience recurrence even with anticoagulant therapy.3,23 Recurrences tend to involve different regions of the aorta, which implies that patients with a thrombotic NADTA have diffuse aortic disease.3

Multiple factors guide the management strategy in thrombotic NADTA, including the characteristics of the thrombus, the patient's comorbidities and symptoms, and the risk factors for thrombus formation.2 Because there are no standard criteria to evaluate the instability of thrombus,34 some investigators suggest that mobile and pedunculated types should be more aggressively treated. Our patient resumed an essentially normal life after anticoagulant therapy, stent-grafting, and bypass surgery to correct the arterial blockage caused by the stent-graft.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Habib Habib, MD, Department of Cardiology, Seton Hall University/Saint Michael's Medical Center, 111 Central Ave., Newark, NJ 07102.

E-mail: Habibhabib78@gmail.com

References

- 1.Reber PU, Patel AG, Stauffer E, Muller MF, Do DD, Kniemeyer HW. Mural aortic thrombi: an important cause of peripheral embolization. J Vasc Surg 1999;30(6):1084–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Tsilimparis N, Hanack U, Pisimisis G, Yousefi S, Wintzer C, Ruckert RI. Thrombus in the non-aneurysmal, non-atherosclerotic descending thoracic aorta–an unusual source of arterial embolism. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41(4):450–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Choukroun EM, Labrousse LM, Madonna FP, Deville C. Mobile thrombus of the thoracic aorta: diagnosis and treatment in 9 cases. Ann Vasc Surg 2002;16(6):714–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Lozano P, Gomez FT, Julia J, M-Rimbau E, Garcia F. Recurrent embolism caused by floating thrombus in the thoracic aorta. Ann Vasc Surg 1998;12(6):609–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.O'Connell JB, Quinones-Baldrich WJ. Proper evaluation and management of acute embolic versus thrombotic limb ischemia. Semin Vasc Surg 2009;22(1):10–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Laperche T, Laurian C, Roudaut R, Steg PG. Mobile thromboses of the aortic arch without aortic debris. A transesophageal echocardiographic finding associated with unexplained arterial embolism. The Filiale Echocardiographie de la Societe Francaise de Cardiologie. Circulation 1997;96(1):288–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Morris ME, Galinanes EL, Nichols WK, Ross CB, Chauvupun J. Thoracic mural thrombi: a case series and literature review. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25(8):1140.e17–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lundervall J. The mechanism of traumatic rupture of the aorta. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1964;62:34–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hazirolan T, Perler BA, Bluemke DA. Floating thoracic aortic thrombus in “protein S” deficient patient. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40(2):381. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Onwuanyi A, Sachdeva R, Hamirani K, Islam M, Parris R. Multiple aortic thrombi associated with protein C and S deficiency. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76(3):319–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rafiq MU, Jajja MM, Qadri SS, Robinson GJ, Cale AR. An unusual presentation of pedunculated thrombus in the distal arch of the aorta after splenectomy for B-cell lymphoma. J Vasc Surg 2008;48(6):1603–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ryu YG, Chung CH, Choo SJ, Kim YS, Song JK. A case of antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with a floating thrombus in the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137(2):500–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Virmani R, Robinowitz M, Geer JC, Breslin PP, Beyer JC, McAllister HA. Coronary artery atherosclerosis revisited in Korean war combat casualties. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1987; 111(10):972–6. [PubMed]

- 14.Modelli ME, Cherulli AS, Gandolfi L, Pratesi R. Atherosclerosis in young Brazilians suffering violent deaths: a pathological study. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kiowski W, Linder L, Stoschitzky K, Pfisterer M, Burckhardt D, Burkart F, Buhler FR. Diminished vascular response to inhibition of endothelium-derived nitric oxide and enhanced vasoconstriction to exogenously administered endothelin-1 in clinically healthy smokers. Circulation 1994;90(1):27–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Dintenfass L. Elevation of blood viscosity, aggregation of red cells, haematocrit values and fibrinogen levels with cigarette smokers. Med J Aust 1975;1(20):617–20. [PubMed]

- 17.Pretorius E, Oberholzer HM, van der Spuy WJ, Meiring JH. Smoking and coagulation: the sticky fibrin phenomenon. Ultrastruct Pathol 2010;34(4):236–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mueck AO, Seeger H. Smoking, estradiol metabolism and hormone replacement therapy. Arzneimittelforschung 2003; 53(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mueck AO, Seeger H. Smoking, estradiol metabolism and hormone replacement therapy. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents 2005;3(1):45–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Brosnan JF, Sheppard BL, Norris LA. Haemostatic activation in post-menopausal women taking low-dose hormone therapy: less effect with transdermal administration? Thromb Haemost 2007;97(4):558–65. [PubMed]

- 21.Irey NS, Norris HJ. Intimal vascular lesions associated with female reproductive steroids. Arch Pathol 1973;96(4):227–34. [PubMed]

- 22.Lamy AL, Roy PH, Morissette JJ, Cantin R. Intimal hyperplasia and thrombosis of the visceral arteries in a young woman: possible relation with oral contraceptives and smoking. Surgery 1988;103(6):706–10. [PubMed]

- 23.Krishnamoorthy V, Bhatt K, Nicolau R, Borhani M, Schwartz DE. Transesophageal echocardiography-guided aortic thrombectomy in a patient with a mobile thoracic aortic thrombus. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011;15(4):176–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Malyar NM, Janosi RA, Brkovic Z, Erbel R. Large mobile thrombus in non-atherosclerotic thoracic aorta as the source of peripheral arterial embolism. Thromb J 2005;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Cohen A, Chauvel C, Abergel E, Albo C, Benhalima B, Valty J. Value of transesophageal echocardiography in the cardiovascular assessment of an ischemic cerebral accident of suspected embolic origin [in French]. Ann Radiol (Paris) 1994;37(1–2):29–40. [PubMed]

- 26.Tunick PA, Perez JL, Kronzon I. Protruding atheromas in the thoracic aorta and systemic embolization. Ann Intern Med 1991;115(6):423–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Goueffic Y, Chaillou P, Pillet JC, Duveau D, Patra P. Surgical treatment of nonaneurysmal aortic arch lesions in patients with systemic embolization. J Vasc Surg 2002;36(6):1186–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Luckeroth P, Steppacher R, Rohrer MJ, Eslami MH. Endovascular therapy for symptomatic mobile thrombus of infrarenal abdominal aorta. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2009;43(5):518–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Luebke T, Aleksic M, Brunkwall J. Endovascular therapy of a symptomatic mobile thrombus of the thoracic aorta. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;36(5):550–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Modarai B, Ali T, Dourado R, Reidy JF, Taylor PR, Burnand KG. Comparison of extra-anatomic bypass grafting with angioplasty for atherosclerotic disease of the supra-aortic trunks. Br J Surg 2004;91(11):1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Piffaretti G, Tozzi M, Caronno R, Castelli P. Endovascular treatment for mobile thrombus of the thoracic aorta. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32(4):664–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Queral LA, Criado FJ. The treatment of focal aortic arch branch lesions with Palmaz stents. J Vasc Surg 1996;23(2):368–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Shames ML, Rubin BG, Sanchez LA, Thompson RW, Sicard GA. Treatment of embolizing arterial lesions with endoluminally placed stent grafts. Ann Vasc Surg 2002;16(5):608–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.De Rango P. Mural thrombus of thoracic aorta: few solutions and more queries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41(4):458–9. [DOI] [PubMed]