Abstract

Prolactin (PRL) is an anterior pituitary hormone which has its principle physiological action in initiation and maintenance of lactation. In human reproduction, pathological hyperprolactinemia most commonly presents as an ovulatory disorder and is often associated with secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea. Galactorrhea, a typical symptom of hyperprolactinemia, occurs in less than half the cases. Out of the causes of hyperprolactinemia, pituitary tumors may be responsible for almost 50% of cases and need to be investigated especially in the absence of history of drug induced hyperprolactinemia. In women with hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea one important consequence of estrogen deficiency is osteoporosis, which deserves specific therapeutic consideration. Problem in diagnosing and treating hyperprolactinemia is the occurrence of the ‘big big molecule of prolactin’ that is biologically inactive (called macroprolactinemia), but detected by the same radioimmunoassay as the biologically active prolactin. This may explain many cases of very high prolactin levels sometimes found in normally ovulating women and do not require any treatment. Dopamine agonist is the mainstay of treatment. However, presence of a pituitary macroadenoma may require surgical or radiological management.

KEY WORDS: Anovulation, galactorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, prolactin, prolactinomas

INTRODUCTION

Prolactin (PRL) plays a central role in a variety of reproductive functions. Initially, even though this hormone was recognized in relation to lactation in women, lately immense interest has been focused on prolactin with respect to its effect on reproduction. Hyperprolactinemia is a condition of elevated prolactin levels in blood which could be physiological, pathological, or idiopathic in origin. Similarly elevated prolactin levels could be associated with severe clinical manifestations on one side of the spectrum or be completely asymptomatic on the other side.

Unlike other tropic hormones secreted by the anterior pituitary gland, prolactin secretion is controlled primarily by inhibition from the hypothalamus and it is not subject to negative feedback directly or indirectly by peripheral hormones. It exercises self-inhibition by a counter-current flow in the hypophyseal pituitary portal system which initiates secretion of hypothalamic dopamine, as well as causes inhibition of pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH). This negatively modulates the secretion of pituitary hormones responsible for gonadal function.

PREVALENCE

It is a common endocrine disorder of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. It occurs more commonly in women. The prevalence of hyperprolactinemia ranges from 0.4% in an unselected adult population to as high as 9-17% in women with reproductive diseases. Its prevalence was found to be 5% in a family planning clinic, 9% in women with adult onset amenorrhea, and 17% among women with polycystic ovary syndrome.[1]

PROLACTIN MOLECULE

Prolactin is a 23 kDa polypeptide hormone (198 amino acid) synthesized in the lactotroph cells of the anterior pituitary gland. Its secretion is pulsatile and increases with sleep, stress, food ingestion, pregnancy, chest wall stimulation, and trauma.

Macroprolactin: Even though monomeric 23 kDa form is the predominant form, prolactin is also present in different molecular forms on which the bioactivity of the hormone depends. Macroprolactinemia denotes the situation in which high levels of the circulating ‘big prolactin’ molecules are present. These big variants of prolactin molecule are of 50 and 150 kDa (PRL-IgG complexes) also known as ‘big prolactin’ and the ‘big-big prolactin’ which have high immunogenic properties, but poor or no biological effect. The ‘big prolactin’ or macroprolactin represents dimers, trimers, polymers of prolactin, or prolactin-immunoglobulin immune complexes. When these big variants circulate in large amounts, the condition is referred to as “macroprolactinemia”, identified as hyperprolactinemia by the commonly used immune assays. Such forms are rarely physiologically active but may register in most prolactin assays.[1] In these situations even though tests determines high levels of circulating prolactin hormone the biological prolactin is normal and thus the lack of clinical symptoms.[2,3] Although a smaller proportion of patients with macroprolactinemia may have symptoms of hyperprolactinemia,[4,5] it should be suspected when typical symptoms of hyperprolactinemia are absent.[6,7] As macroprolactinemia is a common cause of hyperprolactinemia, routine screening for macroprolactinemia could eliminate unnecessary diagnostic testing as well as treatment.[3] Investigation for macroprolactin should always be done in cases of asymptomatic hyperprolactinemic subjects. Many commercial assays do not detect macroprolactin. Polyethylene glycol precipitation is an inexpensive way to detect the presence of macroprolactin in the serum.

BIOLOGICAL ACTION

The main biological action of prolactin is inducing and maintaining lactation. However, it also exerts metabolic effects, takes part in reproductive mammary development[8] and stimulates immune responsiveness.[9] All these effects of prolactin are because it binds to specific receptors in the gonads, lymphoid cells, and liver.[10]

Actual serum prolactin level is the result of a complex balance between positive and negative stimuli derived from both external and endogenous environments. Plenty of mediators of central, pituitary, and peripheral origin take part in regulating prolactin secretion through a direct or indirect effect on lactotroph cells.[2]

Prolactin secretion is under dual regulation by hypothalamic hormones. The predominant signal is tonic inhibitory control of hypothalamic dopamine which traverses the portal venous system to act upon pituitary lactotroph D2 receptors. Other prolactin inhibiting factors include gamma amino butyric acid (GABA), somatostatin, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine. The second signal is stimulatory which is provided by the hypothalamic peptides, thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and dopamine receptor antagonists. Serotonin physiologically mediates nocturnal surges and suckling-induced prolactin rises and is a potent modulator of prolactin secretion. Histamine has a predominantly stimulatory effect due to the inhibition of the dopaminergic system.

Estrogen stimulates the proliferation of pituitary lactotroph cells especially during pregnancy. However, lactation is inhibited by the high levels of estrogen and progesterone during pregnancy. The rapid decline of estrogen and progesterone in the postpartum period allows lactation to commence. During lactation and breastfeeding, ovulation may be suppressed due to the suppression of gonadotropins by prolactin, but may resume before menstruation resumes.

ETIOLOGY

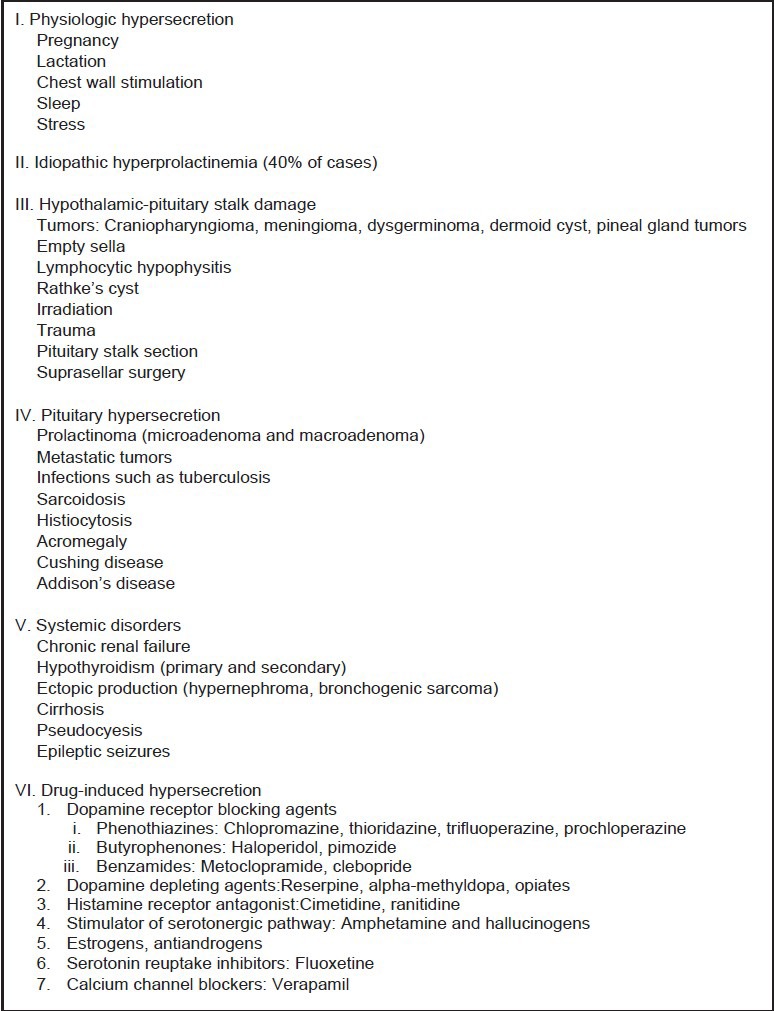

Hyperprolactinemia can be physiological or pathological. Some of the common causes are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Etiology of hyperprolactinemia[11]

Physiological hyperprolactinemia is usually mild or moderate. During normal pregnancy, serum prolactin rises progressively to around 200-500 ng/mL. Many common medications cause hyperprolactinemia usually with prolactin levels of less than 100 ng/mL.

Pathological hyperprolactinemia can be caused by both hypothalamic-pituitary disease (prolactinomas) as well as non-hypothalamic-pituitary disease.

Prolactinomas account for 25-30% of functioning pituitary tumors and are the most frequent cause of chronic hyperprolactinemia.[12] Prolactinomas are divided into two groups: (1) microadenomas (smaller than 10 mm) which are more common in premenopausal women, and (2) macroadenomas (10 mm or larger) which are more common in men and postmenopausal women. Raised prolactin levels can also be caused by pituitary adenomas cosecreting prolactin hormone. Lesions affecting the hypothalamus and pituitary stalk such as nonfunctioning adenomas, gliomas, and craniopharyngiomas also results in prolactin elevation.[13]

Around 40% patients with primary hypothyroidism, 30% patients with chronic renal failure, and up to 80% patients on hemodialysis have mild elevation of prolactin levels. Many patients with acromegaly have prolactin cosecreted with growth hormone.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The predominant physiologic consequence of hyperprolactinemia is hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH) which is due to suppression of pulsatile GnRH. The clinical manifestations of conditions vary significantly depending on the age and the sex of the patient and the magnitude of the prolactin excess. Clinical presentation in women is more obvious and occurs earlier than in men. Women can present with symptoms of oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, galactorrhea, decreased libido, infertility, and decreased bone mass.

It is worth noting that many premenopausal women with hyperprolactinemia do not have galactorrhea, and many with galactorrhea do not have hyperprolactinemia. This is because galactorrhea requires adequate estrogenic or progesterone priming of breast. Conversely, isolated galactorrhea with normal prolactin levels occurs due to increased sensitivity of the breast to the lactotrophic stimulus.[14,15,16] Thus, galactorrhea is very uncommon in postmenopausal women. Approximately 3-10% women with PCOS have coexistent modest hyperprolactinemia.[17]

Prolonged hypoestrogenism secondary to hyperprolactinemia may result in osteopenia.[18] Spinal bone mineral density (BMD) is decreased by approximately 25% in such women and is not necessarily restored with normalization of prolactin levels.[19] Women with hyperprolactinemia and normal menses have normal BMD.[20,21] Hyperprolactinemic women may present with signs of chronic hyperandrogenism such as hirsutism and acne, possibly due to increased dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate secretion from the adrenals,[22] as well as reduced sex hormone binding globulin leading to high free testosterone levels.

Men with hyperprolactinemia may present with erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, infertility, gynecomastia, decreased bone mass, but rarely galactorrhea. Over time, the patient may have diminished energy, reduced muscle mass, and increased risk of osteopenia.[23]

Macroprolactinomas usually present with neurological symptoms caused by mass effects of the tumor. Symptoms include headaches, visual field losses, cranial neuropathies, hypopituitarism, seizures, and cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea.[23]

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Normal serum prolactin levels vary between 5 and 25 ng/ml in females although physiological and diurnal variations occur.[24] Serum prolactin levels are higher in the afternoon than in the morning, and hence should preferably be measured in the morning. Hyperprolactinemia is usually defined as fasting levels of above 20 ng/ml in men and above 25 ng/ml in women[9] at least 2 hours after waking up. Unless the prolactin levels are markedly elevated, the investigation should be repeated before labeling the patient as hyperprolactinemic. Even one normal value should be considered as normal and an isolated raised one should be discarded as spurious. Other common conditions which must be excluded when considering raised prolactin levels are non-fasting sample, excessive exercise, history of drug intake, chest wall surgery or trauma, renal disease, cirrhosis, and seizure within 1-2 hours. These conditions usually cause PRL elevation of <50 ng/ml.

Hyperprolactinemia without an identified cause requires imaging of the hypothalamic-pituitary area. A mildly elevated serum prolactin level may be due to a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma or craniopharyngioma compressing the pituitary stalk, but high prolactin levels are commonly associated with a prolactin secreting prolactinoma.[1] Although computerized axial tomography (CAT) scan can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement provides the best visualization of the sellar area. A prolactinoma is likely if the prolactin level is greater than 250 ng/mL[25] and a level of 500 ng/mL or greater is diagnostic of a macroprolactinoma. Selected drugs including risperidone and metoclopramide may cause prolactin elevations above 200 ng/mL.[26]

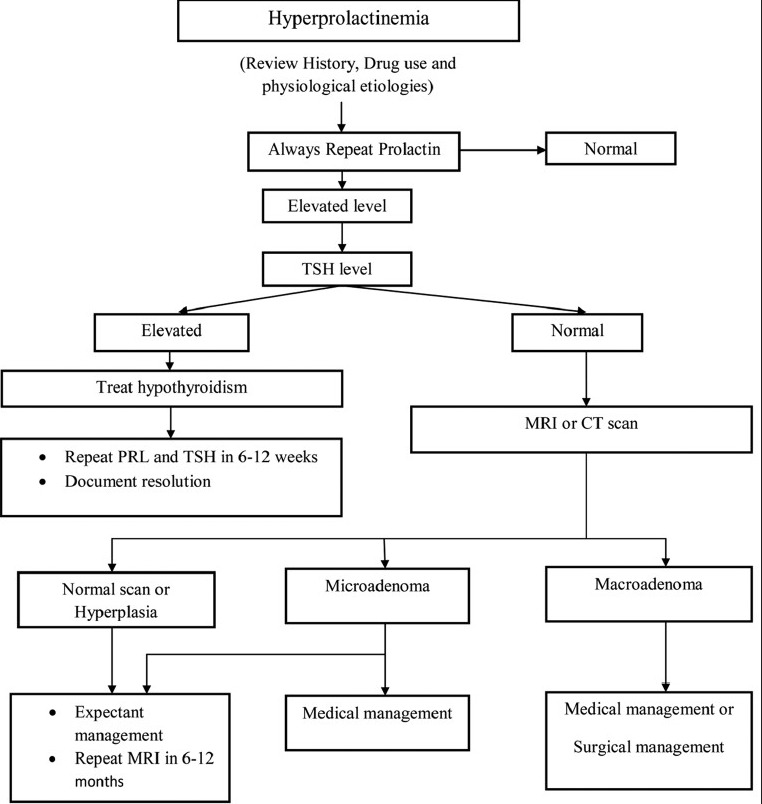

In cases where other causes of hyperprolactinemia have been excluded and no adenoma can be visualized with MRI, the hyperprolactinemia is referred to as “idiopathic” [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Overview of diagnosis and management of hyperprolactinemia

MANAGEMENT

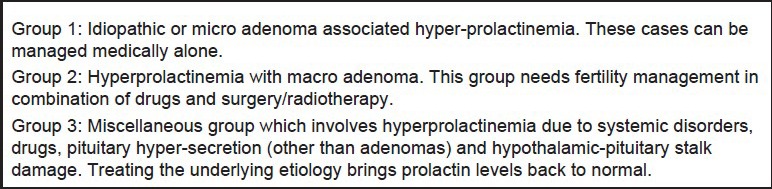

For management purpose, hyperprolatinemics can be broadly divided into three groups [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Management of hyperprolactnemia based on etiology

Group 1

Dopamine agonist is the mainstay of management if fertility is desired or there are symptoms of estrogen deprivation or galactorrhea.

Idiopathic hyperprolactinemia

Bromocriptine is the first option for this condition and has now been used for the longest period of time. Best way is to give it is as continuous therapy and prolactin levels reduce in about a week; ovulation and menstruation resumes in 4-8 weeks. Weekly assessment of progesterone is the most popular method to confirm resumption of ovulatory function in oligo or amennorrhic women. Ovulation rates achieved by medical therapy alone with dopamine agonist are approximately 80-90% if hyperprolactinemia is the only cause for anovulation. In the remaining women, exogenous gonadotropin stimulation can be added along with dopamine agonist to achieve ovulation.

Microadenoma with hyperprolactinemia

Medical management can be undertaken for a period ranging from 18 months to 6 or more years. Tumor expansion may occur during pregnancy in less than 2% of cases. No treatment is required in asymptomatic and very slow growing tumors which do not metastasize. Follow-up is mandatory with yearly estimation of prolactin levels, MRI, and visual fields. However, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to replenish estrogen deficit should be given to all patients with amenorrhea.

Dopamine agonists have been in clinical use for many years and remain the cornerstone for therapy of prolactinomas.[27,28] All (except quinagolide) are ergot alkaloids. Initially it was thought that patients would require lifelong dopamine agonist therapy but the current use has evolved into a dynamic process depending on the patient's requirement. Most commonly used dopamine agonists are bromocriptine and cabergoline. Others are lisuride, pergolide, quinagolide, terguride, and metergoline. Patients who are intolerant or fail to respond to one agent may do well with another.

Side effects associated with these drugs are nausea, vomiting, headache, constipation, dizziness, faintness, depression, postural hypotension, digital vasospasm, and nasal stuffiness. These symptoms are most likely to occur with initiation of treatment or when the dose is increased. One rare but notable side effect is neuropsychiatric symptoms which present as auditory hallucinations, delusion, and mood changes. This may be due to hydrolysis of the lysergic acid part of the molecule. It quickly resolves with discontinuation of the drug.[29] Previous concerns about valvular heart disease[30,31] with the use of these agents have largely been disproved by more recent reports.[32,33]

Bromocriptine is a lysergic acid derivative with a bromine substitute at position 2.[34] It is a strong dopamine agonist which binds to dopamine receptor and directly inhibits PRL secretion. It decreases prolactin synthesis, DNA synthesis, cell multiplication, and overall size of prolactinoma. It has a short half-life and so it requires twice daily administration to maintain optimal suppression of prolactin levels. Intolerance to bromocriptine is common and it is the main indication of using an alternative drug. Tolerance is better when one starts with the lowest possible dose of 1.25 mg/day after dinner and increase the dose gradually by 1.25 mg each week until prolactin levels are normal or a dose of 2.5 mg twice daily is reached which is effective in 66% cases.[14] However, one can start with 7.5 mg/day dosage to save time and 90% will respond.

Another alternative to oral administration is vaginal usage of the same drug which is well tolerated. Vaginal absorption is nearly complete and avoidance of the liver first pass metabolism allows lower therapeutic dosing.[35] It is also available in a long acting form (depot-bromocriptine) for intramuscular injection and a slow release oral form.[36,37] Bromocriptine has good treatment results but the problem is that prolactin returns to elevated levels in 75% of patients after discontinuation of treatment and there is no clinical or laboratory assessment that can predict those patients who will have long-term beneficial result.[38]

Cabergoline shares many characteristics and adverse effects of bromocriptine but has a very long half-life allowing weekly dosing. This is more effective in suppressing prolactin and reducing tumour size.[39] The low rate of side effects and the weekly dosage make cabergoline a better choice for initial treatment. It can also be given vaginally if nausea occurs when taken orally.[40] A dose of 0.25 mg twice per week is usually adequate for hyperprolactinemia. Maximum dose that can be given is 1 mg twice a week.

Though both drugs have been found to be safe in pregnancy, the number of reports studying bromocriptine in pregnancy far exceeds that of cabergoline.

Kisspeptin, when administered exogenously, has the ability to reverse the hypogonadotropic effects of hyperprolactinemia and can also restore pulsatile LH secretion.[41] Treatment with kisspeptin or kisspeptin agonists has potential therapeutic implications in fertility restoration in the future.

Group 2

Macroadenoma with hyperprolactinemia

The aim of the treatment is reduction in tumor mass along with the correction of the biochemical consequences of the hormonal excess including restoration of fertility, prevention of bone loss, and suppression of galactorrhea.[42]

Dopamine agonists are the first line of treatment with surgery and radiotherapy reserved for refractory and medication intolerant patients.[43] Macroprolactinomas regress with medication but the response is variable. Some show prompt shrinkage with low doses while others may require prolonged treatment with higher dosage. Reduction in tumor size can take place in several days to weeks.[12,44]

Transnasal transsphenoidal microsurgical excision of prolactinoma is a straight forward and safe procedure. It is usually recommended for very large tumors, those with suprasellar and frontal extension, and visual impairment persisting after medications. Besides the usual surgical risks, hypopituitarism is a potential long-term effect of surgery and should be discussed with patients as part of the decision-making process. Unfortunately, excision is often incomplete and therefore relapse occurs even though prolactin levels are lower than before. Prolactin levels should be repeated after 4 weeks of starting therapy and then repeated only after 3-6 months depending on symptom reversal. Repeat MRI is done after 6 months of normalization of prolactin levels. Further evaluation is done with 6 monthly prolactin levels. Scanning should be repeated only if symptoms reappear or exacerbate.

There are several possible explanations for the recurrence or persistence of hyperprolactinemia after surgery as listed below:

Tumor may be multifocal in origin

Complete resection is difficult because prolactin producing tumor looks like the surrounding normal pituitary

There may be continuing abnormality of the hypothalamus giving rise to chronic stimulation of the lactotrophs. This can lead to recurrent hyperplasia. However, molecular biology studies indicate that pituitary tumors are monoclonal in origin.[45]

External radiation therapy is only reserved for residual tumor in patients who have undergone surgery and the entire tumor is not removed. It is of very limited benefit in the treatment of these tumors since the response is typically quite modest and delayed.[46] Patients should be warned that such treatment carries a risk of developing hypopituitarism. Bromocriptine has been used in surgical failure or combined surgical and radiological failures.

Group 3

Around 40% patients with primary hypothyroidism have mild elevation of PRL levels that can be normalized by thyroid hormone replacement.[11] Medications that can cause hyperprolactinemia should be discontinued for 48-72 hours if it is safe to do so and serum prolactin level repeated. Sometimes the causative agent is essential for the patient's health (for e.g., a psychotropic agent) but it may cause symptomatic hypogonadism. In these patients, treatment with a dopamine agonist should be avoided since it might compromise the effectiveness of the psychotropic drug and the patient should simply be treated with replacement of sex steroids.

About 30% patients with chronic renal failure and up to 80% patients on hemodialysis have raised prolactin levels. This is probably due to either decreased clearance or increased production of prolactin as a result of disordered hypothalamic regulation of prolactin secretion. Correction of the renal failure by transplantation results in normal PRL levels.

CONCLUSION

As reproductive clinicians, it is important that the pathological relevance of hyperprolactinemia is established before commencing treatment for this endocrinological disorder. Most cases of true hyperprolactinemia are associated with amenorrhea or hormone deprivation in premenopausal women and can be managed by dopamine agonist or hormone replacement therapy respectively.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biller BM, Luciano A, Crosignani PG, Molitch M, Olive D, Rebar R, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia. J Reprod Med. 1999;44(Suppl 12):1075–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: Structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1523–631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibney J, Smith TP, McKenna TJ. The impact on clinical practice of routine screening for macroprolactin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3927–32. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donadio F, Barbieri A, Angioni R, Mantovani G, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A, et al. Patients with macroprolactinaemia: Clinical and radiological features. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:552–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna TJ. Should macroprolactin be measured in all hyperprolactinaemic sera? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:466–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chahal J, Schlechte J. Hyperprolactinemia. Pituitary. 2008;11:141–6. doi: 10.1007/s11102-008-0107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glezer A, Soares CR, Vieira JG, Giannella-Neto D, Ribela MT, Goffin V, et al. Human macroprolactin displays low biological activity via its homologous receptor in a new sensitive bioassay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1048–55. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benker G, Jaspers C, Häusler G, Reinwein D. Control of prolactin secretion. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68:1157–67. doi: 10.1007/BF01815271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halbreich U, Kinon BJ, Gilmore JA, Kahn LS. Elevated prolactin levels in patients with schizophrenia: Mechanisms and related adverse effects. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2003;28(Suppl 1):53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nilsson LA, Roepstorff C, Kiens B, Billig H, Ling C. Prolactin suppresses malonyl-CoA concentration in human adipose tissue. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:747–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang I, Gibson M, Peterson CM. Endocrine disorders. In: Berek JS, editor. Berek and Novak's Gynecology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1069–136. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster J, Scanlon MF. Prolactinomas. In: Sheaves R, Jenkins PJ, Wass JA, editors. Clinical Endocrine Oncology. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1997. pp. 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevan JS, Webster J, Burke CW, Scanlon MF. Dopamine agonists and pituitary tumor shrinkage. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:220–40. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-2-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinberg DL, Noel GL, Frantz AG. Galactorrhea: A study of 235 cases, including 48 with pituitary tumors. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:589–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197703172961103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolis G, Somma M, Van Campenhout J, Friesen H. Prolactin secretion in sixty-five patients with galactorrhea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974;118:91–101. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33651-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd AE, 3rd, Reichlin S, Turksoy RN. Galactorrhea-amenorrhea syndrome: Diagnosis and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:165–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-2-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minakami H, Abe N, Oka N, Kimura K, Tamura T, Tamada T. Prolactin release inpolycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrinol Jpn. 1988;35:303–10. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.35.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klibanski A, Neer RM, Beitins IZ, Ridgway EC, Zervas NT, McArthur JW. Decreased bone density in hyperprolactinemic women. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1511–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012253032605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlechte J, el-Khoury G, Kathol M, Walkner L. Forearm and vertebral bone mineral in treated and untreated hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:1021–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-5-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biller BM, Baum HB, Rosenthal DI, Saxe VC, Charpie PM, Klibanski A. Progressive trabecular osteopenia in women with hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:692–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.3.1517356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klibanski A, Biller BM, Rosenthal DI, Schoenfeld DA, Saxe V. Effects of prolactin and estrogen deficiency in amenorrheic bone loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:124–30. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-1-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biller BM. Hyperprolactinemia. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 1999;44:74–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luciano AA. Clinical presentation of hyperprolactinemia. J Reprod Med. 1999;44(Suppl 12):1085–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melmed S, Jameson JL. Disorders of the anterior pituitary and hypothalamus. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 2076–97. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erem C, Kocak M, Nuhoglu I, Yılmaz M, Ucuncu O. Blood coagulation, fibrinolysis and lipid profile in patients with prolactinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73:502–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kearns AE, Goff DC, Hayden DL, Daniels GH. Risperidone-associated hyperprolactinemia. Endocr Pract. 2000;6:425–9. doi: 10.4158/EP.6.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, Kleinberg DL, Montori VM, Schlechte JA, et al. Endocrine Society. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:273–88. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlechte JA. Long-term management of prolactinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2861–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner TH, Cookson JC, Wass JA, Drury PL, Price PA, Besser GM. Psychotic reactions during treatment of pituitary tumours with dopamine agonists. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:1101–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6452.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motazedian S, Babakhani L, Fereshtehnejad SM, Mojthahedi K. A comparison of bromocriptine and cabergoline on fertility outcome of hyperprolactinemic infertile women undergoing intrauterine insemination. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:670–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahceci M, Sismanoglu A, Ulug U. Comparison of cabergoline and bromocriptine in patients with asymptomatic incidental hyperprolactinemia undergoing ICSI-ET. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:505–8. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horvath J, Fross RD, Kleiner-Fisman G, Lerch R, Stalder H, Liaudat S, et al. Severe multivalvular heart disease: A new complication of the ergot derivative dopamine agonists. Mov Disord. 2004;19:656–62. doi: 10.1002/mds.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rascol O, Pathak A, Bagheri H, Montastruc JL. New concerns about old drugs: Valvular heart disease on ergot derivative dopamine agonists as an exemplary situation of pharmacovigilance. Mov Disord. 2004;19:611–3. doi: 10.1002/mds.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vance ML, Evans WS, Thorner MO. Drugs five years later. Bromocriptine. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:78–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz E, Weiss BE, Hassell A, Schran HF, Adashi EY. Increased circulating levels of bromocriptine after vaginal compared with oral administration. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:882–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merola B, Colao A, Caruso E, Sarnacchiaro F, Briganti F, Lancranjan I, et al. Oral and injectable long-lasting bromocriptine preparations in hyperprolactinemia: Comparison of their prolactin lowering activity, tolerability and safety. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1991;5:267–76. doi: 10.3109/09513599109028448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brue T, Lancranjan I, Louvet JP, Dewailly D, Roger P, Jaquet P. A long-acting repeatable form of bromocriptine as long-term treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas: A multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passos VQ, Souza JJ, Musolino NR, Bronstein MD. Long-term follow-up of prolactinomas: Normoprolactinemia after bromocriptine withdrawal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3578–82. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Cappabianca P, Di Salle F, Rossi FW, Pivonello R, et al. Resistance to cabergoline as compared with bromocriptine in hyperprolactinemia: Prevalence, clinical definition, and therapeutic strategy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5256–61. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.8054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motta T, de Vincentiis S, Marchini M, Colombo N, D’Alberton A. Vaginal cabergoline in the treatment of hyperprolactinemic patients intolerant to oral dopaminergics. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:440–2. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.George JT, Veldhuis JD, Roseweir AK, Newton CL, Faccenda E, Millar RP, et al. Kisspeptin-10 is a potent stimulator of LH and increases pulse frequency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1228–36. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillam MP, Molitch ME, Lombardi G, Colao A. Advances in the treatment of prolactinomas. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:485–534. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, Abs R, Bonert V, Bronstein MD, et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;65:265–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Essaïs O, Bouguerra R, Hamzaoui J, Marrakchi Z, Hadjri S, Chamakhi S, et al. Efficacy and safety of bromocriptine in the treatment of macroprolactinomas. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2002;63:524–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herman V, Fagin J, Gonsky R, Kovacs K, Melmed S. Clonal origin of pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1427–33. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-6-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsagarakis S, Grossman A, Plowman PN, Jones AE, Touzel R, Rees LH, et al. Megavoltage pituitary irradiation in the management of prolactinomas: Long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1991;34:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]