Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of care provided by mid-level health workers.

Methods

Experimental and observational studies comparing mid-level health workers and higher level health workers were identified by a systematic review of the scientific literature. The quality of the evidence was assessed using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria and data were analysed using Review Manager.

Findings

Fifty-three studies, mostly from high-income countries and conducted at tertiary care facilities, were identified. In general, there was no difference between the effectiveness of care provided by mid-level health workers in the areas of maternal and child health and communicable and noncommunicable diseases and that provided by higher level health workers. However, the rates of episiotomy and analgesia use were significantly lower in women giving birth who received care from midwives alone than in those who received care from doctors working in teams with midwives, and women were significantly more satisfied with care from midwives. Overall, the quality of the evidence was low or very low. The search also identified six observational studies, all from Africa, that compared care from clinical officers, surgical technicians or non-physician clinicians with care from doctors. Outcomes were generally similar.

Conclusion

No difference between the effectiveness of care provided by mid-level health workers and that provided by higher level health workers was found. However, the quality of the evidence was low. There is a need for studies with a high methodological quality, particularly in Africa – the region with the greatest shortage of health workers.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer l'efficacité des soins fournis par les agents de santé de niveau intermédiaire.

Méthodes

Des études expérimentales et observationnelles comparant des agents de santé de niveaux intermédiaire et de niveau supérieur ont été identifiées à l'aide d'une revue systématique de la documentation scientifique. La qualité des éléments de preuve a été évaluée à l'aide des critères GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assissment, Development and Evaluation – Méthode d'évaluation des recommandations, de détermination, d'élaboration et d'évaluation), et les données ont été analysées à l'aide d'un gestionnaire d'examen.

Résultats

Cinquante-trois études ont été identifiées, la plupart provenant de pays à revenu élevé, et menées dans des établissements de soins tertiaires. En général, il n'y avait pas de différence entre l'efficacité des soins prodigués par des agents de santé de niveau intermédiaire dans les domaines de la santé maternelle et infantile et des maladies contagieuses et non contagieuses et ceux prodigués par des agents de santé de niveau supérieur. Cependant, les taux de recours à l'épisiotomie et aux analgésiques étaient significativement moins élevés chez les femmes accouchant avec la seule aide d'une sage-femme que chez les femmes prises en charge par des docteurs secondés par des sages-femmes, et les femmes étaient significativement plus satisfaites des soins prodigués par les sages-femmes. Dans l'ensemble, la qualité des éléments de preuve était basse, voire très basse. La recherche a également identifié six études observationnelles, provenant toutes d'Afrique, qui comparaient les soins de praticiens cliniques, de techniciens chirurgicaux ou de cliniciens non-médecins avec les soins prodigués par des médecins. Les résultats étaient généralement similaires.

Conclusion

Aucune différence n'a été constatée entre l'efficacité des soins prodigués par des agents de santé de niveau intermédiaire et ceux fournis par des agents de santé de niveau supérieur. Cependant, la qualité des éléments de preuve était basse. Il est nécessaire d'effectuer des études basées sur une méthodologie de haute qualité, en particulier en Afrique, la région qui manque le plus d'agents de santé.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar la eficacia de la atención proporcionada por los trabajadores sanitarios de nivel intermedio.

Métodos

A través de un examen sistemático de la literatura científica se identificaron diversos estudios experimentales y observacionales que comparaban a los trabajadores sanitarios de nivel intermedio con los de nivel superior. Se evaluó la calidad de las pruebas científicas con ayuda de los criterios GRADE y se empleó el programa Review Manager para el análisis de los datos.

Resultados

Se identificaron 53 estudios, la mayoría de ellos de países de ingresos elevados y que se habían efectuado en centros de atención sanitaria terciaria. En general, no se observaron diferencias entre la eficacia de la atención prestada por los trabajadores de salud de nivel intermedio y la proporcionada por los trabajadores de salud de nivel superior en las áreas de salud materno-infantil y en relación a las enfermedades transmisibles y no transmisibles. Sin embargo, los índices de episiotomía y el uso de analgésicos fueron significativamente inferiores en las mujeres que dieron a luz únicamente con la ayuda de una matrona en comparación con aquellas cuya atención corrió a cargo de médicos que trabajaron conjuntamente con matronas. Las mujeres estuvieron mucho más satisfechas con el trabajo de las matronas. En general, la calidad de las pruebas científicas fue baja o muy baja. La búsqueda también identificó seis estudios observacionales, todos ellos realizados en África, que comparaban la atención de los encargados clínicos y la de los instrumentadores quirúrgicos o clínicos sin licencia para practicar medicina con la de los médicos. Los resultados fueron, en su mayoría, similares.

Conclusión

No se encontró diferencia alguna entre la eficacia de la atención proporcionada por trabajadores sanitarios de nivel intermedio o de nivel superior. No obstante, la calidad de las pruebas científicas era baja. Es necesario realizar estudios con una calidad metodológica alta, especialmente en África, la región con la mayor escasez de personal sanitario.

ملخص

الغرض

تقييم فعالية الرعاية المقدمة من العاملين الصحيين على المستوى المتوسط.

الطريقة

تم تحديد الدراسات التجريبية والقائمة على الملاحظة التي تقارن العاملين الصحيين على المستوى المتوسط والعاملين الصحيين على المستوى الأعلى عن طريق استعراض منهجي للأبحاث العلمية. وتم تقييم جودة البينّات باستخدام معايير تقدير وتطوير وتقييم التوصيات، وتم تحليل البيانات باستخدام مدير المراجعة.

النتائج

تم تحديد ثلاث وخمسين دراسة، معظمها من البلدان المرتفعة الدخل وتم إجراؤها في منشآت الرعاية المتخصصة. وبشكل عام، لم يتم العثور على أي اختلاف بين فعالية الرعاية المقدمة من العاملين الصحيين على المستوى المتوسط في مجالات صحة الأم والطفل والأمراض السارية وغير السارية وتلك المقدمة من العاملين الصحيين على المستوى الأعلى. ومع ذلك، انخفضت معدلات بضع الفرج واستخدام المسكنات بشكل كبير لدى النساء اللاتي يلدن وتلقين الرعاية من القابلات فقط، عنها لدى اللاتي تلقين الرعاية من الأطباء العاملين في فرق مع القابلات، وازداد مستوى رضا النساء عن الرعاية المقدمة من القابلات بشكل كبير. وبشكل عام، كانت جودة البيانات منخفضة أو شديدة الانخفاض. وحدد البحث كذلك ست دراسات قائمة على الملاحظة، جميعها من أفريقيا، قارنت الرعاية المقدمة من العاملين السريريين أو الاختصاصيين الجراحيين أو الخبراء السريريين غير الأطباء بالرعاية المقدمة من الأطباء. وكانت الحصائل متشابهة بشكل عام.

الاستنتاج

لم يتم العثور على اختلاف بين فعالية الرعاية المقدمة من العاملين الصحيين على المستوى المتوسط وتلك المقدمة من العاملين الصحيين على المستوى الأعلى. ومع ذلك، كانت جودة البينّات منخفضة. وثمة حاجة لإجراء دراسات ذات جودة منهجية عالية، لاسيما في أفريقيا – المنطقة التي تعاني من أعلى نقص في العاملين الصحيين.

摘要

目的

评估中级卫生工作者所提供护理的效果。

方法

通过系统回顾科学文献,对比较中级卫生工作者和高级卫生工作者的实验和观察性研究进行确认。使用推荐等级的评估、制定与评价评估、制定和评价标准分级来评估证据的质量,并使用Review Manager分析数据。

结果

确认了53 项研究,这些研究大多数来自高收入国家,并且是在三级医院中执行的。一般而言,在孕产妇和儿童卫生以及传染病和非传染性疾病方面,中级卫生工作者和高级卫生工作者所提供护理的效果没有差别。但是,较之由医生与助产士合作提供护理的产妇,其会阴侧切率和镇痛使用率显著低于只接受助产士护理的产妇,并且产妇对助产士的护理明显更加满意。整体而言,证据的质量较低或非常低。此次研究还确定了六项观察性研究,这些研究都来自非洲,它们对临床人员、外科工作人员和非医师临床人员提供的护理与医生提供的护理进行比较。结局大致相似。

结论

在中级卫生工作者和高级卫生工作者提供的护理效果之间没有发现区别。但是,证据的质量很低。需要进行方法质量较高的研究,尤其是在非洲——该地区卫生工作者最为短缺。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить качество медицинской помощи, предоставляемой средним медицинским персоналом.

Методы

На основе систематического обзора научной литературы были отобраны экспериментальные и обсервационные исследования, в которых сравнивается качество услуг, получаемых от медицинского персонала среднего и более высокого уровня. Качество собранных данных оценивалось на основе методологии GRADE (система градации и оценки качества рекомендаций), собранные данные были проанализированы с помощью программы Review Manager.

Результаты

Было отобрано 53 исследования, главным образом из стран с высокими доходами, проведенных в учреждениях специализированной медицинской помощи. В целом не было выявлено разницы между эффективностью медицинской помощи, оказываемой медперсоналом среднего уровня в области материнского и детского здоровья и инфекционных и неинфекционных заболеваний, и помощью, оказываемой медицинскими работниками более высокого уровня. Однако показатели использования эпизиотомии и анальгезии были значительно ниже при родах женщин, получавших помощь только от акушерок, по сравнению с теми родами, которые вели врачи, работающие в группах с акушерками; и женщины были значительно более удовлетворены уходом акушерок. Но качество этих данных было низким или очень низким. В процессе поиска также было выявлено шесть обсервационных исследований, все из Африки, в которых проводилось сравнение медицинского ухода, получаемого от сотрудников клиник, хирургических техников и медицинских работников, не являющихся врачами. Результаты в целом были сходными.

Вывод

Не обнаружено никаких отличий между эффективностью медицинской помощи, оказываемой медперсоналом среднего уровня, и помощью, оказываемой медицинскими работниками более высокого уровня. Однако качество этих доказательств являлось низким. Существует потребность в изучении данного вопроса с более высоким методологическим качеством, особенно в Африке, регионе с наиболее острой нехваткой работников здравоохранения.

Introduction

In 2000, 189 countries adopted the United Nation’s Millennium Declaration and its eight Millennium Development Goals, including Goals 4, 5 and 6, which are directly related to health. However, progress towards achieving the associated health targets falls far below expectations, especially in developing countries. Recent reviews have clearly identified interventions that can have a positive effect on maternal and child health and neonatal survival but implementing them throughout the general population has been hampered by a lack of trained and motivated health workers.1–6 Moreover, the poor performance of health systems in delivering effective, evidence-based interventions for priority health conditions has been linked to the poor retention, inadequate performance and poor motivation of health workers, as well as to shortages of personnel and their maldistribution. As health systems around the world and the international health community increasingly embrace the goal of universal health coverage, which will inevitably result in greater demands on health systems and existing health workers, the need to address these shortcoming is becoming imperative.7 In parallel, there is growing recognition that skilled and semi-skilled mid-level health workers, who are sometimes referred to as “outreach and facility health workers”, can play a major role in community mobilization and in delivering a range of health-care services.

Although mid-level health workers have been defined in a variety of ways (Table 1), the definitions commonly agree that they will have received shorter training than physicians but will perform some of the same tasks.10 Typically, these workers follow certified training courses and receive accreditation for their work.10 Many, such as nurse auxiliaries and medical assistants, undergo shorter training than physicians and the scope of their practice is narrower, but this is not necessarily the case for all. For example, sometimes nurses and nurse practitioners spend more than 5 years in training and perform some of the same tasks as doctors. Similarly, non-physician clinicians may have, in total, spent an equal amount of time in training as medical doctors and may perform a comparable range of tasks, including surgery. Despite differences in the roles and training of mid-level health workers and despite a continuing struggle for their acceptance, today many countries rely ever more heavily on these workers to improve the coverage and equity of health care.11 Although mid-level health workers have played a vital role in many countries’ health-care systems for over 100 years, interest in them has been renewed only in the past 10 years, principally because of the serious shortage of health workers in many developing countries, the burden of diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the emerging importance of other conditions, such as noncommunicable diseases. Many African and Asian countries have successfully invested in these workers.12–15

Table 1. Definitions of mid-level health workers.

| Source of definition | Definition of mid-level health workers |

|---|---|

| WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 20018 | “Front-line health workers in the community who are not doctors but who have been trained to diagnose and treat common health problems, to manage emergencies, to refer appropriately and to transfer the seriously ill or injured for further care.” |

| Dovlo, 20049 | “Health cadres who have been trained for shorter periods and required lower entry educational qualifications, to whom are delegated functions and tasks normally performed by more established health professionals with higher qualifications.” |

| Lehman, 200810 | “Mid-level workers are health-care providers who are not professionals but who render health care in communities and hospitals. They have received less (shorter) training and have a more restricted scope of practice than professionals. In contrast to community or lay health workers, they have a formal certificate and accreditation through their countries’ licensing bodies. Some may work under the direct or indirect supervision of professionals, while others work independently and indeed lead health care teams, particularly in primary and community care.” |

WHO, World Health Organization.

Our aim was to test the hypothesis that mid-level health workers are as effective as higher level health workers at providing good quality care in priority areas of the health service. We also hoped to increase understanding of their effectiveness and of how they can best be integrated into national health-care systems.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of studies on the role of mid-level health workers in delivering to the general population health-care services that are associated with the achievement of Millennium Development Goals on health and nutrition or with the management of noncommunicable diseases. We included all randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, controlled before-and-after trials and interrupted time-series studies. Less rigorously designed studies, such as observational (cohort and case–control) and descriptive studies, were also examined to understand the context within which mid-level health worker programmes are implemented, the types of health-care providers involved, the types of interventions delivered and the outcomes obtained. We aimed to compare the effectiveness of: (i) different kinds of mid-level health workers; (ii) mid-level health workers and doctors or community health workers; and (iii) mid-level health workers working alone or in a team.

For the purpose of this study, a mid-level health worker was defined as a health-care provider who is not a medical doctor or physician but who provides clinical care in the community or at a primary care facility or hospital. He or she may be authorized and regulated to work autonomously, to diagnose, manage and treat illness, disease and impairments, or to engage in preventive care and health promotion at the primary- or secondary-health-care level. The definition includes midwives, nurses, auxiliary nurses, nurse assistants, non-physician clinicians and surgical technicians (Table 2). Workers who specialize in health administration or who perform only administrative tasks and those who provide rehabilitative or dentistry services were excluded. However, no type of patients or recipient of health services was excluded.

Table 2. Categories of mid-level health workers.

| Broad category | Definition16,17 | Titles |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse | A graduate nurse who has been legally authorized (i.e. registered) to practise after examination by a state board of nurse examiners or similar regulatory authority. Their education typically includes 3, 4 or more years in a nursing school and leads to a university or postgraduate university degree or equivalent. | Registered nurse, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, advanced practice nurse, clinical practice nurse, practice nurse, licenced nurse, diploma nurse, nurse with a Bachelor of Science degree |

| Midwife | A person who has been assessed and registered by a state midwifery regulatory authority or similar regulatory authority. Midwives offer care to childbearing women during pregnancy, labour, birth and the postpartum period. They also care for neonates and assist the mother with breastfeeding. Their education lasts 3, 4 or more years in a nursing school and leads to a university or postgraduate university degree or equivalent. A registered midwife has the full range of midwifery skills. | Registered midwife, midwife, community midwife |

| Auxiliary nurse or auxiliary nurse midwife | Auxiliary nurses and auxiliary nurse midwives undergo some training in secondary school. A period of on-the-job training may be included and sometimes formalized in apprenticeships. An auxiliary nurse has basic nursing skills but no training in nursing decision-making. Auxiliary nurse midwives provide care to women during the prenatal, intrapartum and postpartum periods and to neonates. | Auxiliary nurse, auxiliary nurse midwife, auxiliary midwife, nurse assistant |

| Non-physician clinician | A non-physician clinician is a health worker who is not trained as a physician but who is able to perform many of the diagnostic and clinical functions of a medical doctor and who has more clinical skills than a nurse. He or she usually provides advanced advisory, diagnostic, curative (including minor surgery but not, according to the definition adopted in this report, caesarean section, except in Mozambique) and preventive medical services. The requisites and training vary from country to country but often include 3 or 4 years of education after secondary school in clinical medicine, surgery and community health. | Clinical officer, medical assistant, physician assistant |

| Surgical technician | Surgical technicians perform all the functions of non-physician clinicians. However, they are predominantly responsible for performing caesarean sections. | Medical and surgical technician |

A systematic search of the Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase and Cinahl databases, the Latin America and the Caribbean database LILACS and the Social Sciences Citation Index was performed, without language restrictions. Articles in both peer-reviewed and grey literature were included and the authors of relevant papers were contacted to help identify additional published or unpublished works.

The main health-care outcomes we considered were morbidity, mortality, outcomes associated with care delivery, health status, quality of life, service utilization and the patient’s satisfaction with care. Two review authors independently extracted all outcome information. Data were collected on all health workers and care recipients involved, on health-care settings and on each study’s design and outcomes.

The statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Risk ratios (RRs) and mean differences, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively. Study heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and χ2 statistics. Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in each study using a form describing standard criteria, which was obtained from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group.18 We analysed the quality of the evidence supporting study findings using the approach developed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group.19,20 The quality of the evidence for each outcome was rated high, moderate, low or very low.

Results

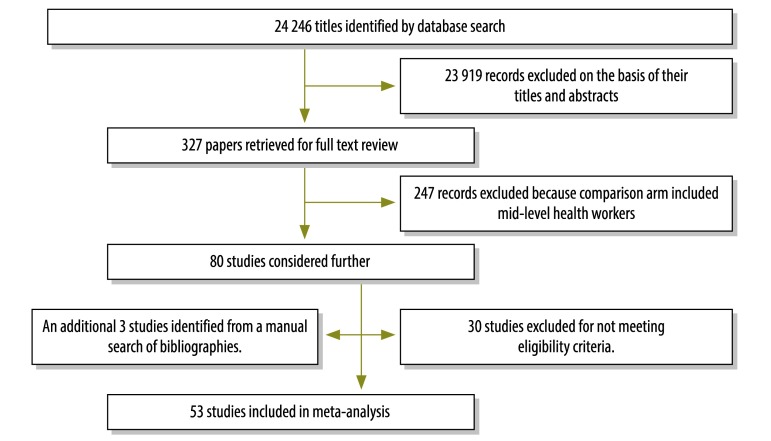

The search identified 24 246 database records, which led to the retrieval of documentation on 327 studies for a full text review (Fig. 1). Of the 327, 53 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review (Table 3, available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/11/13-118786). Most studies compared either care provided by midwives with that provided by doctors working in a team along with midwives or care provided by nurses with that provided by doctors. Moreover, most were conducted in high-income countries and at tertiary care facilities. The studies were experimental in design and their results were pooled for the meta-analysis (Table 4). Since the evidence in all studies was found to be of low or very low quality, as assessed using GRADE criteria, the findings of the meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution.

Fig. 1.

Database search for experimental studies of mid-level health workers’ effectiveness, 1973–2012

Table 3. Experimental studies included in meta-analysis of mid-level health workers’ effectiveness, 1973–2012.

| Study | Study design | Health worker comparison | Study characteristics | Study participants | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begley, 201121 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with general practitioners | Intervention: antenatal care from midwives in a maternity unit or an outreach clinic and, if desired, from the woman’s general practitioner. When complications arose, women were transferred to a consultant-led unit according to agreed criteria. | Recipients: pregnant women. (n = 1653; 1101 in the intervention arm and 552 in the control arm) | Health status, including rates of caesarean delivery, episiotomy and epidural anaesthesia |

| Control: standard care from a consultant-led unit. | |||||

| Health-care setting: general hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Australia | |||||

| Harvey, 199622 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: a team of seven midwives provided antenatal and intrapartum care in a hospital and postpartum care in the community. | Recipients: women at a low risk of complications who requested and qualified for the intervention group. (n = 101) | Rates of caesarean delivery, episiotomy and epidural anaesthesia |

| Controls: usual care from obstetricians or general practitioners at a variety of city hospitals. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Canada | |||||

| Hundley, 199423 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with consultant gynaecologist | Intervention: patients randomized to the midwife-led unit were seen by a midwife throughout delivery with minimal intervention from other hospital staff. Midwives were responsible for delivering and maintaining care. | Recipients: low-risk pregnant women from the general population. (n = 2844) | Maternal and perinatal morbidity |

| Controls: care from a consultant in a delivery unit. | |||||

| Health-care setting: medical centre. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Aberdeen, Scotland | |||||

| MacVicar, 199324 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: team of two midwifery sisters assisted by eight staff midwives provided hospital-based antenatal and intrapartum care and hospital care only after childbirth. | Recipients: women with a low risk of complications. (n = 2304) | Induction, augmentation, intrapartum complications, need for pain relief, perineal status, satisfaction with care, birth weight, Apgar score and maternal and fetal mortality |

| Controls: shared antenatal care from general practitioner and midwives and intrapartum care from hospital staff. | |||||

| Health-care setting: tertiary-care hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Leicester, England | |||||

| Marks, 200325 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with general practitioners | Intervention: all women in the study received the basic pattern of care provided by the midwifery service at King’s College London; that is, each woman was seen by a midwife 8 to 12 times during pregnancy, on commencement of labour, at delivery and then as required from a minimum of 10 days postpartum to a maximum of 28 days. | Recipients: women who had had at least one episode of a major depressive disorder, as defined by DSM-III-R criteria, either in the past or during the current pregnancy. (n = 51) | Any antenatal illness, new episode of illness after antenatal registration, any postnatal illness and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score 4 weeks after giving birth |

| Controls: women in the control group received a mixture of care at antenatal clinics after giving birth: either from a general practitioner alone or from a general practitioner and a community midwife. However, none of these included continuity of care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: King’s College London, London, England | |||||

| McLachlan, 200826 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: care from midwives who attended information sessions on the need to adhere to the clinical practice guidelines of the Royal Women's Hospital. | Recipients: pregnant women. (n = 2307; 1150 in the intervention arm and 1157 in the control arm) | Health status, rates of caesarean delivery, episiotomy and epidural anaesthesia |

| Controls: care from doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: teaching hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Australia | |||||

| Di Napoli, 200427 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: breastfeeding counselling. | Recipients: mothers who had recently given birth. (n = 605; 303 in the intervention and 302 in the control arm) | Breastfeeding 4 months and 6 months postpartum |

| Control: no specific intervention. | |||||

| Health-care setting: in the community. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Rome, Italy | |||||

| Rowley, 199528 | Stratified randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: care from a midwifery team. | Recipients: women attending an antenatal clinic. (n = 405) | Antenatal, intrapartum and neonatal events, satisfaction and costs |

| Controls: routine care. | |||||

| Health-care setting: teaching hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Australia | |||||

| Small, 200029 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with a consultant gynaecologist | Intervention: debriefing by midwives who were experienced in talking with women about childbirth, able to listen with empathy to women's accounts and aware of the common concerns and issues arising for women after an operative birth. The content of the discussion was determined by each woman's experiences and concerns and up to 1 hour was made available for each session. | Recipients: women who had operative deliveries were identified from maternity ward records at least 24 hours after delivery by two research midwives. (n = 917) | Maternal depression and overall health status |

| Controls: no debriefing by midwives. | |||||

| Health-care setting: teaching hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Melbourne, Australia | |||||

| Turnbull, 199630 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: women received care at midwifery development unit. | Recipients: women with normal healthy pregnancies. (n = 648) | Postnatal care, preparation for parenthood |

| Controls: women received traditional care. | |||||

| Health-care setting: major urban teaching hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Glasgow, Scotland | |||||

| Waldenström, 200131 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: team midwifery care in a hospital’s public delivery wards 24 hours a day; when no woman cared for by her team was in labour, the midwife cared for women outside her team. Each midwife worked on average one shift per week in the hospital antenatal clinic where she saw only women enrolled in team care. | Recipients: patients who presented to the Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne. (n = 464) | Satisfaction with care, maternal complication rates, procedures performed and infant outcomes such as neonatal death |

| Controls: standard care, mostly from doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: teaching hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Australia | |||||

| Law, 199932 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with general practitioners | Intervention: care exclusively from midwives. | Recipients: pregnant women assessed as being at a low risk on admission to a labour ward. (n = 1050) | Caesarean delivery, normal vaginal delivery, episiotomy, Apgar score |

| Controls: care from doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: teaching hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | |||||

| Wolke, 200233 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives compared with paediatric senior house officers | Intervention: neonate examination by midwives, which was usually carried out 6 to 24 hours after birth. | Recipients: mothers and neonates. (n = 826) | Maternal satisfaction with examination |

| Controls: neonate examination by junior paediatricians. | |||||

| Health-care setting: district general hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: south-east England | |||||

| Eren, 198334 | Controlled comparative trial | Auxiliary nurse midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: intrauterine device insertion by auxiliary nurse midwives. | Recipients: healthy women. (n = 501 in the Philippines; 250 in the intervention arm and 251 in the control arm); (n = 495 in Turkey; 257 in the intervention arm and 238 in the control arm) | Health status, successful intrauterine device insertion |

| Controls: insertion by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: teaching hospitals. | |||||

| Geographical setting: the Philippines and Turkey | |||||

| Dusitsin, 198035 | Randomized controlled trial | Mid-level health workers and nurse midwives compared with doctors | Intervention: tubal ligation by mid-level health workers. Controls: tubal ligation by doctors. Health-care setting: operating theatre. Geographical setting: Thailand |

Recipients: healthy women. (n = 292; 143 in the intervention arm and 149 in the control arm) |

Health status, postoperative complications, difficulties during the operation |

| Warriner, 200636 | Randomized controlled trial | Midwives and doctor’s assistants compared with doctors | Intervention: manual vacuum aspiration performed by a mid-level health worker, with a follow-up 10 to 14 days later. | Recipients: women who presented for an induced abortion at up to 12 weeks’ gestation were informed of the study and invited to participate. (n = 1160) in South Africa; (n = 1734) in Viet Nam | The primary outcome was abortion complications |

| Controls: manual vacuum aspiration performed by a doctor. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: South Africa and Viet Nam | |||||

| Warriner, 201137 | Randomized controlled trial | Certified nurses and nurse auxiliary midwives compared to doctors | Intervention: randomized patients were managed by mid-level health workers who had full responsibility for the management of each case. Abortions were performed according to Nepalese health authority guidelines. | Recipients: women seeking a termination early in the first trimester of pregnancy. (n = 542) | The primary outcome was the successful abortion rate |

| Controls: similar care from doctors with similar responsibilities. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Nepal | |||||

| Sanne, 201038 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: primary care from primary health-care nurses. The experimental nurse monitoring strategy involved doctor-initiated ART, which was monitored by the nurses. | Recipients: HIV-positive patients. (n = 404) | The primary study outcome was the composite endpoint of the various treatment-limiting events that could occur on first-line ART |

| Controls: primary care from doctors. The care strategy was consistent with the routine management of patients in the current South African ART programme, which is based on treatment initiated and monitored by a doctor. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care in two towns. | |||||

| Geographical setting: South Africa | |||||

| Mann, 199839 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: study 1 evaluated the effectiveness of standardized psychiatric assessment by a practice nurse with feedback of information to a general practitioner. Study 2 evaluated the same assessment by and feedback from a practice nurse combined with nurse-assisted follow-up care. In study 1, nurses interviewed patients and scored them using the Beck Depression Inventory. In study 2, nurses were also responsible for follow-up care. | Recipients: patients diagnosed as depressed by a general practitioner. (n = 577; 158 in study 1 and 419 in study 2) | Change in Beck Depression Inventory scores 4 and 5 and change in the proportion of patients fulfilling DSM-III criteria for major depression, as determined by the nurse assessment interview |

| Controls: patients were seen and managed by a general practitioner. | |||||

| Health-care setting: clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Liverpool, England | |||||

| Du Moulin, 200740 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: in a cluster-randomized study, women were referred to a continence nurse who, guided by a protocol, assessed the patients and gave advice about therapy, lifestyle and medications. If progress was disappointing, therapy was revised. | Recipients: low-risk pregnant women from the general population. (n = 45) | The primary outcome was the number of incontinence episodes |

| Controls: women received usual care. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: the Netherlands | |||||

| Gordon, 197441 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurse clinicians compared with doctors | Intervention: primary medical care was provided by a nurse clinician. | Recipients: patients who presented to hospital outpatient clinics. (n = 169; 82 in the intervention arm and 87 in the control arm) | Correct diagnosis, frequency of visits and clinical status |

| Controls: care was provided by attending physicians in a general medical clinic. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: New York, United States | |||||

| Hemani, 199942 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care provided by a nurse practitioner. | Recipients: adult patients. (n = 150) | Specialty care, primary care, emergency and walk-in visits and hospitalizations over a 1-year period |

| Controls: care provided by a resident or attending physician. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care clinic. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Veterans Affairs medical centre, United States | |||||

| Katz, 200443 | Randomized controlled trial (secondary analysis) | Licenced practice nurses compared with medical officers | Intervention: counselling provided by licenced practice nurses. | Recipients: adult smokers. (n = 1221) | Proportion of patients who received counselling as recommended by guidelines |

| Controls: counselling provided by medical officers. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary health care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: United States | |||||

| Kinnersley, 200044 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: patients seen by a nurse practitioner. Patients who were prepared to consult either a general practitioner or a nurse practitioner were informed about the study in general terms. Consent was obtained when patients attended the surgery and were told which clinician they would see. All practices had a trained member of staff to manage the study under the supervision of the project research officer. | Recipients: patients seeking a same-day consultation. (n = 652) | Patients’ satisfaction with care, resolution of symptoms and concerns and patients' intentions regarding seeking care in the future |

| Controls: patients seen by a general practitioner. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: 10 general practices in south Wales and south-west England | |||||

| Strömberg, 200345,46 | Randomized controlled trial | Cardiac nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care was provided in a nurse-led heart failure clinic, which was staffed by specially educated, experienced cardiac nurses who took responsibility for making protocol-led changes in medication. The first follow-up visit took place 2 to 3 weeks after hospital discharge. During that visit, the nurse evaluated the degree of heart failure and the treatment received, provided education about heart failure and gave social support to the patient and his or her family. | Recipients: patients hospitalized for heart failure. (n = 106) | All-cause mortality and all-cause hospital admission after 12 months |

| Controls: patients received usual care from primary care physicians in accordance with current guidelines. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Linköping University, Sweden | |||||

| Moher, 200147 | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: setting up a disease register and a procedure for the systematic recall of patients to a nurse-led clinic (nurse recall group). | Recipients: patients aged 55–75 years. (n = 1906) | Adequate assessment of risk factors |

| Controls: setting up a disease register and a procedure for the systematic recall of patients to a general practitioner (general practitioner recall group). | |||||

| Health-care setting: 21 general practices. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Warwickshire, England | |||||

| Sakr, 199948 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurse practitioners compared with doctors | Intervention: patients were first managed by a nurse practitioner who carried out a clinical assessment. Assessments were transcribed afterwards to maintain blinded conditions. Patients were then assessed by an experienced accident and emergency physician (i.e. a research registrar) who completed a research assessment but took no part in the clinical management of the patients. | Recipients: patients attending an accident and emergency department. (n = 727) | The primary outcome measure was the adequacy of the care provided |

| Controls: patients were first managed by a junior doctor. | |||||

| Health-care setting: accident and emergency department at a general hospital. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Sheffield, England | |||||

| Smith, 200549 | Randomized controlled trial | Respiratory nurse specialists compared with doctors | Intervention: in addition to usual care, patients received a 6-month psychoeducational programme of home visits and telephone calls from a supervised respiratory nurse specialist. | Recipients: patients with a confirmed diagnosis of severe asthma who had been admitted to hospital. (n = 92) | The primary outcome was asthma symptom control |

| Controls: patients received usual care from primary care and secondary care clinics, which included an asthma assessment every 3 to 6 months. | |||||

| Health-care setting: hospital and primary care asthma clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Norfolk and Suffolk, England | |||||

| Stein, 197450 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurse practitioners compared with doctors | Intervention: patients were randomized to a consultation with a nurse practitioner, which included history-taking, physical examination, ordering tests and referrals. | Recipients: patients diagnosed with type-2 diabetes. (n = 23) | The primary outcome was diabetic status |

| Controls: patients were managed by an internist. | |||||

| Health-care setting: hospital clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Gainsville, Florida, United States | |||||

| Chambers, 197751,52 | Interrupted time series | Family practice nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care was provided by family practice nurses who were employed to provide health care to local residents. | Recipients: patients in all age groups. (n = 1167) | Utilization of primary health-care services and hospital services and economic effect of deploying a family practice nurse |

| Controls: care was provided by doctors at a local hospital. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care in two villages. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Ontario, Canada | |||||

| Caine, 200253 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurse practitioners compared with doctors | Intervention: care was provided by a nurse practitioner. | Recipients: patients aged over 18 years attending a bronchiectasis clinic with moderate or severe disease confirmed by high-resolution computed tomography. (n = 80) | Number of hospital admissions, health-related quality of life, satisfaction with care and compliance with care |

| Controls: care was provided by a general practitioner. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Lung Defence Clinic, Papworth Hospital, England | |||||

| Chambers, 197854 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: families were allocated to nurse-led primary care. | Recipients: families. (n = 868) | Health status |

| Controls: families received doctor-led primary care. | |||||

| Health-care setting: health-care clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Canada | |||||

| Chinn, 200255 | Randomized controlled trial | Dermatology nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: a trained dermatology nurse holding an ENB 393 certificate in dermatology demonstrated techniques for applying medication, gave advice and provided education in a single 30-minute session. Patients were also provided with leaflets from a drug company that did not promote a product and which covered topics in a one-page format. | Recipients: children aged under 16 years visiting a general practitioner for dermatitis. (n = 240) | The primary outcomes were quality of life, as assessed by the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index and the Infant's Dermatitis Quality of Life Index, and the effect on the family, as assessed by the Family Dermatitis Index |

| Controls: patients received usual care from a general practitioner. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Middlesborough, Teeside, England | |||||

| Cox, 200056 | Prospective follow-up study (data analysed as a case–control study) | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: patients were seen by a nurse. | Recipients: patients aged over 2 years presenting with a sore throat to a doctor or practice nurse during normal working hours. (n = 188) | Sore throat settled, median number of days for sore throat to settle, number of patients requiring analgesia, reconsultation rate, dissatisfaction rate and recollection of advice about home remedies |

| Controls: patients were seen by a doctor. | |||||

| Health-care setting: clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: United Kingdom | |||||

| D’Eramo–Melkus, 200457 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | Registered nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: registered nurses provided information on diabetes care. Dietary habits were addressed by a dietician and other lifestyle modifications were encouraged. | Recipients: low-risk, pregnant, black African women from the general population. (n = 25) | Weight, body mass index, haemoglobin A1c level, knowledge about diabetes, self-efficacy and diabetes-related emotional distress |

| Controls: management was provided by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Pennsylvania, United States | |||||

| Dierick–van Daele, 200958 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: patients with common complaints were randomized to be seen by a nurse practitioner. | Recipients: patients who attended a medical practice in selected areas for an appointment during the study period. (n = 759) | Patients’ perception of the quality of care, effectiveness of consultation |

| Controls: patients with similar complaints were seen by a general practitioner. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: the Netherlands | |||||

| Federman, 200559 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: treatment provided by a nurse. | Recipients: patients with dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus or hypertension. (n = 19 660) | Haemoglobin A1c level, low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol level and blood pressure |

| Controls: treatment provided by a doctor. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Connecticut, United States | |||||

| Houweling, 200960 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care from nurses, who provided treatment to correct glycaemia, blood pressure and lipid profiles according to a protocol. | Recipients: patients with type-2 diabetes. (n = 84) | Haemoglobin A1c level, total cholesterol level, low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol level and total cholesterol to high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol ratio |

| Controls: similar care from doctors (i.e. internists). | |||||

| Health-care setting: clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: the Netherlands | |||||

| Mundinger, 200061 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: patients were assessed and followed up by nurse practitioners, who had the same independence as doctors. | Recipients: adult patients. (n = 806) | Health status at consultation and follow-up |

| Controls: patients were seen by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: New York, United States | |||||

| Myers, 199762 | Follow-up study | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care provided by nurses. | Recipients: patients with acute medical conditions. (n = 1000) | Morbidity |

| Controls: care provided by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: United Kingdom | |||||

| Rushforth, 200663 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with senior house officers | Intervention: preoperative assessment by nurses before day surgery. | Recipients: children. (n = 595) | Ability to detect clinically significant abnormalities |

| Controls: assessment by senior house officers. | |||||

| Health-care setting: preoperative clinic. | |||||

| Geographical setting: England | |||||

| Sharples, 200264 | Randomized, controlled, crossover trial | Nurse practitioners compared with doctors | Intervention: nurse practitioner-led care, during which patients underwent routine tests followed by a consultation that involved clinical assessment and discussion of a management plan. | Recipients: patients aged over 18 years with bronchiectasis. (n = 80) | Forced vital capacity, 12-minute walk test results, number of exacerbations of infection that required intravenous antibiotics, number of hospital admissions, health-related quality of life |

| Controls: doctor-led care following a similar procedure. | |||||

| Health-care setting: bronchiectasis outpatient clinic. | |||||

| Geographical setting: United Kingdom | |||||

| Shum, 200065 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care was managed by nurses, who took the patient's history, performed a physical examination, offered advice and treatment, issued prescriptions (which required a doctor's signature) and referred the patient to the doctor when appropriate. | Recipients: patients who requested and were given a same-day appointment by a receptionist. (n = 1815) | Patients’ general satisfaction with care as assessed using a consultation satisfaction questionnaire |

| Controls: care was managed by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: five general practices. | |||||

| Geographical setting: England | |||||

| Venning, 200066 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurse practitioners compared with doctors | Intervention: the patient’s first medical encounter was with a nurse practitioner, who was responsible for history-taking, physical examination, ordering tests, diagnosis and writing prescriptions to be signed by a general practitioner. | Recipients: patients consulting general practices. (n = 503) | Patients’ satisfaction with care, health status, repeat visits within 2 weeks and costs |

| Controls: patients were managed by a general practitioner. | |||||

| Health-care setting: 20 general practices. | |||||

| Geographical setting: England and Wales | |||||

| Sackett, 197467 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: care provided by nurses. | Recipients: families. (n = 4325) | Health status, patients’ satisfaction with care and costs |

| Controls: care provided by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Canada. | |||||

| Babor, 200568 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: alcohol screening and brief intervention by nurses. | Recipients: hazardous and harmful drinkers. (n = 3449) | Percentage of patients screened |

| Control: alcohol screening and brief intervention by doctors. | |||||

| Health-care setting: primary care clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: United States | |||||

| McIntosh, 199769 | Randomized controlled trial | Nurses compared with doctors | Intervention: brief advice (i.e. 5 minutes) from a physician, followed by two 30-minute sessions with a nurse practitioner using cognitive behavioural strategies. | Recipients: hazardous drinkers. (n = 159) | Reduction in hazardous drinking and problems related to drinking over 12 months of follow-up |

| Controls: the same strategy, but with two 30-minute sessions with a physician. | |||||

| Health-care setting: family practice clinics. | |||||

| Geographical setting: Australia |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition revised; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 4. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mid-level health workers, 1973–2012.

| Clinical area and outcome measure | RR (95% CI) | Meta-analysis |

Study heterogeneity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | No. of participants | I2 (%) | P for χ2 | |||

| Midwife vs obstetrician or doctor in team with midwives | ||||||

| Antenatal hospitalization | 0.95 (0.79–1.13) | 2 | 1 794 | 47 | 0.17 | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | 1.02 (0.54–1.92) | 3 | 2 460 | 48 | 0.14 | |

| No intrapartum analgesia | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | 3 | 7 419 | 0 | 0.94 | |

| Use of intrapartum opiate analgesia | 0.85 (0.71–1.00) | 6 | 9 411 | 89 | < 0.0001 | |

| Use of intrapartum regional analgesia | 0.87 (0.81–0.93) | 8 | 9 415 | 0 | 0.56 | |

| Augmentation or artificial oxytocin during labour | 0.85 (0.71–1.00) | 8 | 12 143 | 89 | < 0.0001 | |

| Induction of labour | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 7 | 9 440 | 59 | 0.02 | |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 8 | 13 616 | 62 | 0.01 | |

| Instrumental vaginal birth | 1.10 (0.81–1.50) | 8 | 13 388 | 88 | < 0.0001 | |

| Episiotomy | 0.85 (0.78–0.92) | 8 | 13 205 | 25 | 0.23 | |

| Caesarean section | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | 8 | 12 144 | 11 | 0.34 | |

| Intact perineum | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 6 | 10 105 | 70 | 0.005 | |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | 0.53 (0.25–1.14) | 6 | 8 604 | 90 | < 0.001 | |

| Fetal or neonatal death | 0.94 (0.56–1.58) | 6 | 11 562 | 13 | 0.33 | |

| Preterm birth | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | 5 | 9 210 | 0 | 0.58 | |

| Admission to neonatal intensive care | 0.97 (0.77–1.23) | 8 | 13 980 | 62 | 0.01 | |

| Auxiliary nurse midwife vs doctor | ||||||

| Incomplete abortion | 0.93 (0.45–1.90) | 1 | 1 032 | NA | NA | |

| Complication during manual vacuum aspiration | 3.07 (0.16–59.1) | 1 | 2 789 | NA | NA | |

| Adverse event after manual vacuum aspiration | 1.36 (0.54–3.40) | 1 | 2 761 | NA | NA | |

| Complication after tubal ligation | 2.43 (0.64–9.22) | 1 | 292 | NA | NA | |

| Referral to a specialist after intrauterine device insertion | 0.81 (0.31–2.09) | 1 | 996 | NA | NA | |

| Nurses vs doctors | ||||||

| Communicable diseases | ||||||

| ART failure | 1.08 (0.39–2.14) | 1 | 812 | NA | NA | |

| Noncommunicable diseases | ||||||

| Management of depression | 1.28 (0.83–1.98) | 1 | 139 | NA | NA | |

| Repeat consultation for a noncommunicable disease | 0.90 (0.35–2.32) | 3 | 2 394 | 93 | < 0.0001 | |

| Improved physical functioning | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 4 | 3 603 | 78 | 0.004 | |

| Attendance at a follow-up visit for a chronic condition | 1.26 (0.95–1.67) | 3 | 4 022 | 84 | 0.002 | |

| Attendance at an emergency department after receiving care | 1.02 (0.87–1.14) | 2 | 2 648 | 0 | 0.91 | |

| Satisfaction with noncommunicable disease care | 0.20 (0.14–0.26) | 4 | 4 903 | 90 | < 0.0001 | |

| Compliance with drug treatment | 1.24 (1.03–1.48) | 1 | 62 | NA | NA | |

| Death by 12-month follow-up | 0.36 (0.17–0.79) | 1 | 106 | NA | NA | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; RR, risk ratio.

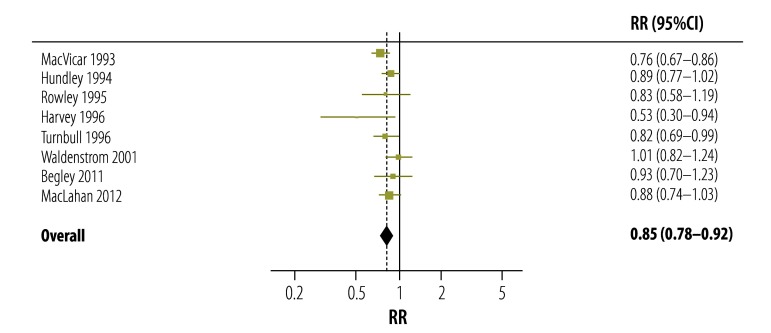

Thirteen of the 53 studies21–33 compared the care provided by midwives with that provided by doctors working in a team with midwives. On meta-analysis, no significant difference in the antenatal hospitalization rate was found between care provided by midwives alone and that provided by doctors working with midwives (RR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.79–1.13). However, the absence of intrapartum analgesia was more likely with care from midwives alone (RR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.96–1.33), but not significantly so, and the use of opiate or regional anaesthesia was significantly less likely (Table 4). Episiotomy was also significantly less likely with care from midwives alone (Fig. 2). However, there was no significant difference in rates for the induction of labour, instrumental delivery or caesarean section (Table 4). The postpartum haemorrhage rate was not significantly lower with care from midwives alone and there was no significant difference between the groups in the rate of fetal or neonatal death, preterm birth or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the risk of episiotomy when pregnancy care is provided only by midwives versus when it is provided by obstetricians or other types of doctors as part of a team including midwives, 1993–2012

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

Note: The values to the left of the 1 indicate a lower risk of episiotomy when pregnancy care is provided only by midwives and those to the right of 1 indicate a higher risk when the care is administered by obstetricians or other types of doctors as part of a team including midwives.

In one study, women were significantly more satisfied with antenatal care provided by midwives alone but there was no significant difference between the groups in satisfaction with intrapartum or postpartum care.31 Turnball et al.30 also reported that women were more satisfied with care from midwives alone than care from doctors working with midwives in a team. Wolke et al.33 compared the level of satisfaction with health workers in general between groups of patients managed by midwives and those managed by junior paediatricians: the care provided by midwives was perceived as being significantly better than that provided by physicians (RR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.10–1.37).

Four of the 53 studies34–37 compared auxiliary nurse midwives with doctors. There was no significant difference in the likelihood of an incomplete abortion between groups of patients managed by auxiliary nurse midwives and those managed by doctors (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.45–1.90). Nor was the likelihood of a complication during (RR: 3.07; 95% CI: 0.16–59.1) – or an adverse event after (RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.54–3.40) – manual vacuum aspiration significantly greater with auxiliary nurse midwives. Similarly, there was no difference between the groups in postoperative complications in women who underwent tubal ligation or in those who were referred to a specialist after insertion of an intrauterine device (Table 4).

One study38 compared the effects of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in patients managed by nurses and those managed by doctors. There was no significant difference in the likelihood of ART failure between groups of patients managed by nurses and those managed by doctors (RR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.39–2.14). Nor was there any difference in mortality, failure of viral suppression or immune recovery between the groups.

The search also identified one study39 that compared nursing care of depression in the general population with standard care. There was no significant difference in measures of depression between patients managed by nurses compared with those managed by physicians (RR: 1.28; 95% CI: 0.83–1.98).

Twenty-eight studies40–45,47–51,53–69 compared the effectiveness of care provided by nurses and care provided by doctors in patients with chronic diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes. Most concerned secondary and tertiary care in developed countries. The meta-analysis showed that care provided by nurses was as effective as care provided by doctors: no significant difference between the groups was found in the need for a repeat consultation, improved physical functioning, attendance at follow-up visits or attendance at an emergency department after receiving care (Table 4). However, dissatisfaction was significantly lower with care received from nurses than with that received from doctors (RR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.14–0.26). The likelihood of death at 12-month follow-up was also lower with care from nurses and the likelihood of compliance with drug treatment was higher (Table 4). However, these last two findings are based on the results of only one study.

Observational studies

All of the lower quality, prospective observational studies identified came from Africa and compared care delivered by clinical officers, surgical technicians or non-physician clinicians with that delivered by doctors.

Six observational studies compared the effectiveness of care provided by clinical officers and surgical technicians with that of care provided by doctors.70–75 Detailed descriptions of the interventions and types of mid-level health workers involved in these studies are provided in Table 5 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/11/13-118786). Since the studies were not experimental in design, data could not be pooled for analysis. Two studies from Malawi compared the outcomes of surgical procedures carried out by clinical officers and medical officers (i.e. doctors).70,71 In the prospective cohort study from Malawi, there was no significant difference in postoperative maternal health outcomes, such as fever, wound infection, the need for re-operation and maternal death, after emergency obstetric procedures performed by clinical officers or by medical officers (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.95–1.03). In particular, there was no significant difference in the likelihood of a stillbirth with procedures performed by clinical officers (RR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.52–1.09) or in the likelihood of early neonatal death (RR: 1.40; 95% CI: 0.51–3.87). Although 22 maternal deaths occurred in 1875 procedures performed by clinical officers compared with 1 in 256 procedures performed by medical officers, the difference was not significant. In a prospective cohort study from Mozambique,72 haematomas occurred significantly more often after surgery performed by a surgical technician than after surgery performed by an obstetrician (odds ratio: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.3–3.9). Finally, a retrospective cohort study from the United Republic of Tanzania73 found no difference in maternal mortality or perinatal mortality between care provided by an assistant medical officer and that provided by a medical officer.

Table 5. Observational studies of mid-level health workers’ effectiveness,1996–2010.

| Study | Country | Study design | Health workers | Objective | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chilopora, 200770 | Malawi | Prospective cohort study | Health workers: clinical officers compared with medical officers (i.e. doctors). Training: clinical officers were trained locally for 3 years. After a 1-year internship, they were licensed to practise independently. Responsibilities: performing major emergency and elective surgery. The Government of Malawi has been training clinical officers since 1974. |

To determine the extent of major surgical work carried out by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi and to assess the quality of surgical care from postoperative outcomes. | Health-care outcomes, including morbidity |

| McGuire, 200871 | Malawi | Cohort study | Health workers: clinical officers compared with nurses and medical officers. Training: not reported. Responsibilities: not reported. |

To identify innovative, alternative and complementary means of delivering ART that can be used to scale up access to treatment. | Health behaviour, such as adherence to treatment, and health-care outcomes, such as mortality |

| McCord, 200973 | United Republic of Tanzania | Retrospective cohort study | Health workers: assistant medical officers compared with medical officers. Training: assistant medical officers were selected from practising clinical officers on the basis of recommendations and examination results. They received another 2 years of clinical training, including 3 months on surgery and 3 months on obstetrics, during which they were expected to have carried out at least five caesarean sections. After graduation, they were licensed to practise medicine and surgery. Responsibilities: practising medicine and surgery. The United Republic of Tanzania started training assistant medical officers to perform caesarean sections and other forms of emergency surgery in 1963. |

To assess the quality of care provided by assistant medical officers (i.e. non-physician clinicians); a prospective review was carried out of all patients admitted with obstetrical complications to district-level hospitals in two regions. | Health-care outcomes, including mortality |

| Gimble-Sherr, 200874 | Mozambique | Retrospective cohort study | Health workers: clinical officers versus medical officers. Training: not reported. Responsibilities: not reported. |

To evaluate the quality of care provided by clinical officers (tecnicos de medicina) who initiated ART and followed up patients. | Health behaviour, such as adherence to treatment |

| Labhardt, 201075 | Cameroon | Uncontrolled before-and-after study | Health workers: non-physician clinicians compared with medical officers. Training: non-physician clinicians were trained in the same way as medical officers and took on many of their diagnostic and therapeutic functions. |

To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of systematically integrating hypertension and diabetes care into the primary health-care services provided by 75 facilities staffed by non-physician clinicians in eight rural districts of Cameroon. | Change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure |

| Pereira, 199672 | Mozambique | Prospective cohort study | Health workers: surgical technicians compared with obstetricians. Training: surgical technicians underwent a 3-year course on the principles of surgery and anaesthesiology and surgical techniques and methods. In Mozambique, government training of surgical technicians began in 1984. |

To evaluate the outcomes of caesarean delivery, with particular attention to postoperative complications. | Health-care outcomes, including morbidity |

ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Discussion

The meta-analysis showed that the outcomes of numerous interventions in the areas of maternal and child health and communicable and noncommunicable diseases were similar when the interventions were performed by mid-level health workers or higher level health workers. However, this finding must be interpreted with caution as the evidence obtained in the systematic review was generally of low or very low quality.

Mid-level health workers play an important role in maternal and child health since midwives are the primary health-care providers in many settings. The results of our meta-analysis indicate that antenatal care provided by midwives alone gave comparable results on most outcome measures to care provided by doctors working in a team with midwives. In addition, mothers were more satisfied with neonatal examinations performed by midwives alone. Midwives can provide continuity of care after childbirth and can advise mothers on other health-care issues concerning neonates, such as breastfeeding.

Mid-level health workers often care for patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Our meta-analysis indicated that patients were significantly more satisfied with care received from nurses than from doctors, though the evidence available was of low quality. Moreover, care provided by nurses was as effective as that provided by doctors. Another consideration is that consultations with mid-level health workers are less expensive for patients.

If health-related Millennium Development Goals are to be achieved, health systems will have to be strengthened so that more countries can deliver a wider range of health services on a much larger scale. It has been claimed that better quality health services could be achieved using the existing workforce, but there is compelling evidence that the number of people with access to health-care services is directly correlated with the number of health service providers.76 Furthermore, there is also a correlation between the health of the population and the density of qualified health-care workers.77 Thus, the number of health-care workers has a positive effect not only on access to health care but also on health outcomes. Clearly, any strategy that aims to increase the scope or reach of the health-care services must consider long-, medium- and short-term initiatives for increasing the skills and retention of health-care workers.

Although the use of mid-level health workers instead of medical doctors has proved successful in various contexts, such as in performing surgery, providing health-care services, health promotion and education and providing ART, the quality of care can be poor when mid-level health workers are not properly supervised or are inadequately trained.78 Moreover, these factors can also have a negative effect on staff retention. Once it has been accepted that less-qualified health-care workers can provide as good a service as more qualified workers, attention should shift to optimizing the skills mix of the workforce. This would mitigate the effect of personnel shortages and help countries achieve the Millennium Development Goals.

This meta-analysis provides evidence supporting the concept of task-sharing, which is defined as the situation in which health-care tasks are shared, as part of a team-based approach to the delivery of care, with either existing or new health workers who have been trained for only a limited period or within only a narrow field. Task-sharing can help achieve the new paradigm of universal health coverage as well as health-related Millennium Development Goals. In addition, mid-level health workers are less costly to train and employ than doctors and they are easier to retain in rural areas. However, it must be remembered that task-sharing alone cannot produce large-scale changes where there is a shortage of personnel. Any task-sharing strategy should be implemented alongside other strategies designed to increase the total number of health-care workers.79–82

The main obstacle to ensuring that mid-level health workers can help improve health outcomes is that they are often ignored by government policies, health workforce strategies and health system support measures, despite their widespread use. Until these workers are more comprehensively taken into account and supported, their potential contribution will not be fully realized.

This review has several limitations. First, most studies reviewed did not fully describe the characteristics of the mid-level health workers involved; in particular, the level and amount of training and supervision provided were not reported. Second, the meta-analysis included few studies of the role of mid-level health workers in HIV prevention and care, mental health or nutrition. Third, the quality of the evidence in the studies we identified was low or very low and, in particular, the majority of studies from Africa on non-physician clinicians and clinical officers were not experimental. Therefore, the results of these studies could not be pooled to generate evidence on the effectiveness of mid-level health workers.

There is a need for more studies of a high methodological quality, particularly experimental studies in primary health care and developing countries. In addition, further research is required on the effectiveness of mid-level health workers in low- and middle- income settings, where the challenge of accessing essential health services is greatest. There is also a remarkable dearth of information on the cost-effectiveness of programmes involving these health workers and on whether these programmes help ensure that care can be accessed on an equitable basis. Finally, there is a need for a systematic review to identify factors that determine whether interventions involving mid-level health workers are sustainable when scaled-up.

In conclusion, we found no difference between the effectiveness of care provided by mid-level health workers and that provided by higher level health workers. However, the quality of the evidence was low or very low. Better quality trials with longer follow-ups are needed, particularly in Africa. Countries in danger of missing health-related Millennium Development Goals should continue to scale up health-care interventions involving community health workers and mid-level health workers. Both national and subnational policies are needed to reduce the shortfall in human resources for health: the skills required by mid-level health workers and their roles should be clearly defined with reference to the level of demand from the local community and changing disease patterns in the country.

Funding:

The review was supported financially by the Global Health Workforce Alliance.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhutta ZA, Ali S, Cousens S, Ali TM, Haider BA, Rizvi A, et al. Interventions to address maternal, newborn, and child survival: what difference can integrated primary health care strategies make? Lancet. 2008;372:972–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Haws RA, Yakoob MY, Lawn JE. Delivering interventions to reduce the global burden of stillbirths: improving service supply and community demand. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell OMR, Graham WJ. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368:1284–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370:1358–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haws RA, Thomas AL, Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL. Impact of packaged interventions on neonatal health: a review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22:193–215. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resolution A/RES.33/63. Global health and foreign policy. In: General Assembly of the United Nations [Internet]. Resolutions. New York: WHO; 2013 (A/RES/33/63). Available from: http://www.who.int/trade/foreignpolicy/en/ [accessed 26 August 2013].

- 8.Mid-level and nurse practitioners in the Pacific: models and issues Manila: World Health Organization, Western Pacific Regional Office; 2001. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/wpro/2001/a76187.pdf [accessed 26 August 2013].

- 9.Dovlo D. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa: a desk review. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehman U. Mid-level health workers. The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes: a literature review Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/MLHW_review_2008.pdf [accessed 26 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Task shifting to tackle health worker shortages Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: www.who.int/healthsystems/task_shifting_booklet.pdf [accessed 26 August 2013].

- 12.Zulu l. Clinical officers (CO) and health care delivery in Zambia: a response to physician shortage Lusaka: CDC Global AIDS Program. Available from: http://csis.org/files/media/csis/events/080324_zulu.pdf [accessed 4 July 2013].

- 13.Hounton SH, Newlands D, Meda N, De Brouwere V. A cost-effectiveness study of caesarean-section deliveries by clinical officers, general practitioners and obstetricians in Burkina Faso. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruk ME, Pereira C, Vaz F, Bergström S, Galea S. Economic evaluation of surgically trained assistant medical officers in performing major obstetric surgery in Mozambique. BJOG. 2007;114:1253–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira C, Cumbi A, Malalane R, Vaz F, McCord C, Bacci A, et al. Meeting the need for emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: work performance and histories of medical doctors and assistant medical officers trained for surgery. BJOG. 2007;114:1530–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Optimizing the delivery of key interventions to attain MDGs 4 and 5: background document for the first expert ‘scoping’ meeting to develop WHO recommendations to optimize health workers’ roles to improve maternal and newborn health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- 17.Mullan F, Frehywot S. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 2007;370:2158–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute [Internet]. EPOC resources. Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. Ottawa: OHRI; 2013. Available from: http://epoc.cochrane.org/search/google-appliance/Suggested%20risk%20of%20bias%20criteria [accessed 26 August 2013].

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org [accessed 26 August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Begley C, Devane D, Clarke M, McCann C, Hughes P, Reilly M, et al. Comparison of midwife-led and consultant-led care of healthy women at low risk of childbirth complications in the Republic of Ireland: a randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey S, Jarrell J, Brant R, Stainton C, Rach DA. A randomized, controlled trial of nurse-midwifery care. Birth. 1996;23:128–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1996.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hundley VA, Cruickshank FM, Lang GD, Glazener CMA, Milne JM, Turner M, et al. Midwife managed delivery unit: a randomised controlled comparison with consultant led care. BMJ. 1994;309:1400–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6966.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacVicar J, Dobbie G, Owen-Johnstone L, Jagger C, Hopkins M, Kennedy J. Simulated home delivery in hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:316–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb12972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]