Abstract

Human resources for health (HRH) will have to be strengthened if universal health coverage (UHC) is to be achieved. Existing health workforce benchmarks focus exclusively on the density of physicians, nurses and midwives and were developed with the objective of attaining relatively high coverage of skilled birth attendance and other essential health services of relevance to the health Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). However, the attainment of UHC will depend not only on the availability of adequate numbers of health workers, but also on the distribution, quality and performance of the available health workforce. In addition, as noncommunicable diseases grow in relative importance, the inputs required from health workers are changing. New, broader health-workforce benchmarks – and a corresponding monitoring framework – therefore need to be developed and included in the agenda for UHC to catalyse attention and investment in this critical area of health systems. The new benchmarks need to reflect the more diverse composition of the health workforce and the participation of community health workers and mid-level health workers, and they must capture the multifaceted nature and complexities of HRH development, including equity in accessibility, sex composition and quality.

Résumé

Les ressources humaines de la santé devront être renforcées pour pouvoir réaliser la couverture sanitaire universelle. Les points de référence existants des effectifs de santé se concentrent exclusivement sur la densité des médecins, infirmiers et sages-femmes, et ils ont été développés avec l'objectif d'atteindre une couverture relativement élevée des accouchements médicalisés et des autres services de santé essentiels qui sont importants pour la réalisation des objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement (OMD) de la santé. Cependant, la réalisation de la couverture sanitaire universelle ne dépendra pas seulement de la disponibilité d'un nombre approprié de professionnels de la santé, mais également de la distribution, de la qualité et de la performance des effectifs de santé disponibles. En outre, comme le nombre des maladies non transmissibles ne cesse de croître, les contributions requises de la part des professionnels de la santé sont en train de changer. Des points de référence nouveaux et plus larges des effectifs de santé – et un cadre de suivi correspondant – doivent donc être développés et inclus dans l'agenda pour la couverture sanitaire universelle afin de catalyser l'attention et les investissements dans ce domaine critique des systèmes de santé. Les nouveaux points de référence doivent refléter la composition plus diverse des effectifs de santé et la participation des agents sanitaires des collectivités et des agents sanitaires de niveau intermédiaire, et ils doivent saisir la nature polymorphe et la complexité du développement des ressources humaines de la santé, y compris en ce qui concerne l'équité dans l'accessibilité, la composition sexospécifique et la qualité.

Resumen

Es fundamental fortalecer la acción de los recursos humanos en sanidad (RHS) para alcanzar la cobertura universal de la salud (CUS). Los parámetros de referencia actuales sobre el personal sanitario se centran exclusivamente en la densidad de médicos, enfermeros y comadronas, y se desarrollaron con el fin de alcanzar una cobertura relativamente alta de asistencia especializada durante el parto y otros servicios de salud esenciales, que fueran para lograr los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio (ODM). Sin embargo, la consecución de la cobertura universal de la salud no solo depende de la disponibilidad de un número adecuado de personal sanitario, sino también de la distribución, la calidad y el desempeño del personal sanitario disponible. Además, la contribución necesaria por parte del personal sanitario cambia a medida que la importancia de las enfermedades no transmisibles crece relativamente. Por lo tanto, es necesario desarrollar e incluir en el programa otros parámetros de referencia más amplios y actuales, así como su marco de seguimiento correspondiente, de modo que los trabajadores comunitarios de salud puedan catalizar la atención y la inversión en esta área clave del sistema sanitario. Los nuevos puntos de referencia deben reflejar la composición más plural del personal sanitario y la participación de los trabajadores comunitarios de salud, así como de los trabajadores sanitarios de nivel medio. De esta manera, deben captar las múltiples facetas y complejidades del desarrollo de los recursos humanos para sanidad, incluyendo la equidad en la accesibilidad, la composición por sexo y la calidad.

ملخص

سوف يتعين تعزيز الموارد البشرية الصحية إذا كانت هناك رغبة في تحقيق التغطية الصحية الشاملة. وتركز الأسس المرجعية القائمة للقوى العاملة الصحية بشكل حصري على كثافة الأطباء والممرضات والقابلات، وتم تطويرها بهدف بلوغ التغطية المرتفعة نسبياً لخدمات التوليد التي يقدمها أشخاص مهرة وغيرها من الخدمات الصحية الأساسية ذات الصلة بالأهداف الإنمائية للألفية في مجال الصحة. وعلى الرغم من ذلك، لن يعتمد بلوغ التغطية الصحية الشاملة على إتاحة الأعداد الكافية من العاملين الصحيين فحسب، ولكنه سيعتمد كذلك على توزيع القوى العاملة الصحية المتاحة ونوعيتها وأداءها. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نتيجة لنمو الأمراض غير السارية بأهمية نسبية، فإن الإسهامات المطلوبة من العاملين الصحيين تتغير. ولذلك، ثمة حاجة لوضع أسس مرجعية جديدة أوسع نطاقاً للقوى العاملة الصحية – وإطار رصد مقابل - وإدراجها في جدول الأعمال للتغطية الصحية الشاملة بغية تسريع الاهتمام والاستثمار في هذا الجانب الهام من النظم الصحية. ويتعين أن تعكس الأسس المرجعية الجديدة التركيبة الأكثر تنوعاً للقوى العاملة الصحية ومشاركة العاملين في مجال الصحة المجتمعية والعاملين الصحيين من المستوى المتوسط، ويجب أن تستوعب الطبيعة متعددة الأوجه لتطوير الموارد البشرية الصحية وتعقيداتها، بما في ذلك الإنصاف في الإتاحة والتركيبة من الجنسين والجودة.

摘要

要实现全民医保(UHC),就必须强化卫生人力资源(HRH)。现有卫生人力基准仅仅关注医生、护士和助产士的密度,其发展目标在于实现熟练助产和其他卫生千年发展目标(MDG)相关基本卫生服务的较高覆盖率。但是,实现UHC不仅依赖于足够数量卫生工作者的可及性,还在于可用卫生劳动力的分布、质量和绩效。此外,随着非传染性疾病相对重要性的提高,对卫生工作者所提供服务的要求也在变化。因此,需要制定更广泛的卫生劳动力基准以及相应的监控框架,并将其纳入UHC日程中,以便促成对卫生系统这一关键领域的关注和投入。新的基准需要反映更加多样的卫生劳动力组合以及社区卫生工作者和中级卫生工作者的参与,并且必须把握HRH发展的多样化和复杂性,包括可及性、性别组成和质量方面的公平性。

Резюме

Для достижения всеобщего охвата медико-санитарной помощью (ВОМСП), необходимо усилить кадровые ресурсы здравоохранения (КРЗ). Существующие в настоящее время методы оценки достаточности кадров здравоохранения сосредоточены исключительно на обеспеченности населения врачами, медсестрами и акушерками и были разработаны с целью достигнуть относительно высоких показателей по количеству профессиональных акушеров и других важных медицинских служб в соответствии с Целями тысячелетия в области развития здравоохранения. Тем не менее, достижение всеобщего охвата зависит не только от адекватного количества работников здравоохранения, но также от распределения, качества и профессиональных показателей доступных кадровых ресурсов здравоохранения. Кроме того, с ростом относительной важности лечения неинфекционных заболеваний меняются требования к работникам здравоохранения. Поэтому должны быть разработаны и включены в программу действий по ВОМСП новые, более широкие методы оценки кадровых ресурсов здравоохранения, а также соответствующая система наблюдения. Это поможет активизировать привлечение внимания и инвестиций к этой исключительно важной области системы здравоохранения. Новые методы оценки должны отражать многообразный состав кадровых ресурсов здравоохранения и задействование местных медработников, а также работников здравоохранения среднего звена. Кроме того, эти оценки должны отражать многопрофильность и сложность развития КРЗ, включая равенство при обеспечении доступности, половой состав и качество подготовки.

Introduction

The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)1 have been credited with catalysing a greater focus on the development priorities they targeted – poverty reduction, gender equality, primary education, maternal and child health, control of major diseases, environmental issues, and partnerships for development – and with mobilizing the relevant resources. With three of the MDGs being health-related, health is awarded a high priority in the current framework. The progress being made towards achieving these three goals is inequitable within and across countries, but despite this, many countries are recording improvements in health outcomes.2

However, limitations in the MDG framework – and particularly in the health-related MDGs – are being recognized: a lack of attention to equity,3 the neglect of health issues that were not explicitly included in any of the MDGs, and the fragmentation of efforts targeted at the different health priorities (the latter might have contributed to a narrowly selective focus on development assistance for health).4 The targets and indicators currently used for the health-related MDGs focus on increasing the coverage of some priority health services – such as skilled birth attendance – and on improving health outcomes in relation to maternal health, child health and infectious diseases. However, none of the MDG targets refers explicitly to the health system actions required to attain such objectives. Yet it has been evident for over a decade that only by overcoming the structural deficiencies of health systems – including those related to governance, the health workforce, information systems, health financing and supply chains – will it be possible to improve specific outcomes for individual diseases or population subgroups.5

Although econometric analyses have confirmed that an adequate health workforce is necessary for the delivery of essential health services and improvement in health outcomes,6,7 there have been systemic failures in the planning, forecasting, development and management of human resources for health (HRH).8,9 This has led to unacceptable variations in the availability, distribution, capacity and performance of health workers, and these have resulted, in turn, in uneven quality and coverage of health services. In many low-income countries, acute shortages in the health workforce have been compounded by the emigration of health workers to high-income countries that offer better working conditions. The situation has heightened a sense of injustice that culminated in the adoption, in 2010, of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel.10

Health workforce benchmarks

The world health report 2006 included an estimate of the minimum density threshold of physicians, nurses and midwives deemed generally necessary to attain a high coverage of skilled birth attendance: 2.28 per 1000 population.9 According to the statistics available when the report was published, 57 countries fell below this benchmark and an additional 4.3 million health workers would be required to achieve the minimum density globally.

Thanks to its grounding in evidence, its relative simplicity and the fact that it could be easily standardized, the minimum density of physicians, nurses or midwives suggested in The world health report 2006 – 2.28 per 1000 population – has become the most widely used health workforce “target”. It was adopted in the commitments of the Group of Eight (G8) in 200811 and has served as a basis for several monitoring and accountability processes that were either focused on the health workforce12 or had a different and broader focus.13 However, this benchmark focuses exclusively on physicians, nurses and midwives and was developed with the objective of attaining relatively high coverage of selected essential health services of relevance to the health MDGs. In today’s world, it is no longer adequate in the health workforce discourse for at least four reasons:

The evidence underpinning the threshold value was based on data on immunization coverage and skilled birth attendance. No consideration was given to health workforce requirements with respect to a wider range of health services, including the control and treatment of noncommunicable diseases.

The benchmark only allows the identification of inadequacies in the numbers of health workers. In the attainment of universal health coverage (UHC), many other challenges of equal – if not greater – importance exist, such as issues relating to access to, and the quality and performance of, the health workforce that were not captured by the simple density-based benchmark. Aspects such as distribution, responsiveness, affordability and productivity were crucially missing.

The macroeconomic implications of attaining the density benchmark have not been examined. It has been estimated that some low-income countries would have to allocate 50% of their gross domestic product to health to be able to reach the benchmark.14

The benchmark only relates to physicians, nurses and midwives. However, community health workers15,16 and mid-level health workers17 can also improve the availability and accessibility of health services while maintaining – when appropriately trained and managed – quality standards that are similar to those of cadres undergoing longer training. Despite a growing evidence base and a significant political momentum in support of their role, including through the global One Million Community Health Workers Campaign and similar initiatives,18,19 these cadres are often operating at the margins of health systems and are largely excluded from HRH information systems and benchmarks.

A few other benchmarks have been used, such as the Sphere standards.20 However, these benchmarks – which call for at least one physician and 50 community health workers for every 50 000 population – are only of primary relevance to humanitarian operations in refugee settings.

Evolving health workforce needs

The renewed focus on UHC in the health policy discourse – which culminated in December 2012 in the adoption of a United Nations General Assembly resolution on global health and foreign policy – has contributed to a wider recognition of the need for an “adequate skilled, well-trained and motivated [health] workforce”.21

The progressive realization of the right to health for all people – and of UHC – will entail a wide array of actions to address the specific needs of each country. As national health systems in low- and middle-income countries try to broaden the services they provide to cover noncommunicable diseases as well, new demands will be made on their health workers. Population demands for more equitable access to health care of good quality will also have to be reflected in efforts at securing greater accessibility of health workers – especially in rural and other underserved areas22 – and improving their competence and performance. There will also be an increasing demand for greater efficiency: in general, the countries that are facing the greatest obstacles to the attainment of UHC are also the most fiscally constrained. Affordable approaches to boost the performance of health workers are urgently required. There may be trade-offs between the broader HRH needs entailed in the UHC paradigm and the financial constraints faced by many countries. It may be possible to increase the cost-effectiveness of an expanding health system by awarding more prominent roles to community health workers and mid-level health workers. Similarly, the adoption of appropriate management systems and incentive structures could help to optimize the performance of existing health workers and reduce wasteful spending.23

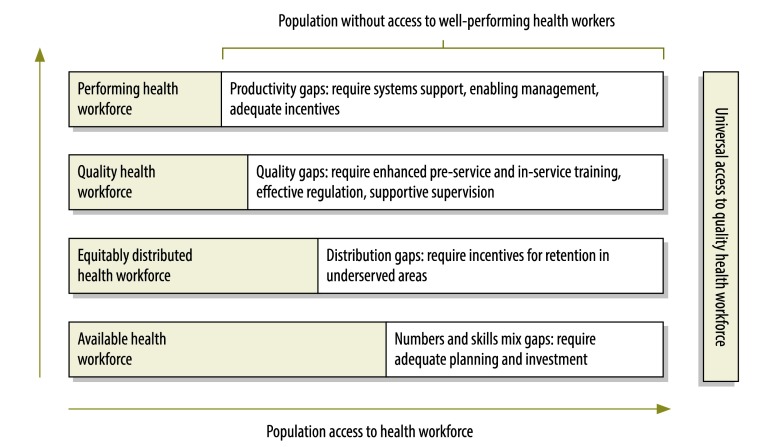

Guaranteeing UHC is a multifaceted endeavour. To approach the issue through the health workforce lens, it is necessary to go beyond mere numbers and address gaps in equitable distribution, competency, quality, motivation, productivity and performance. Improving access to effective coverage will not be possible otherwise (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Human resources for health actions required to achieve universal health coverage

Source: Jim Campbell and Giorgio Cometto (2012), adapted from Tanahashi (1978).

On the path towards UHC, fundamental changes will have to be adopted by countries and by the global health community in relation to how health workers are trained, deployed, managed and supported.24 The role of the public sector in shaping health labour market forces will also have to be strengthened. A critical element in this endeavour is the inclusion of HRH benchmarks and of a corresponding monitoring framework in the UHC agenda.

Aiming for universal health coverage

HRH are not an end in themselves but the indispensable means to achieving improved health outcomes. Aware of the importance of measurable targets and linked accountability mechanisms in stimulating action, countries and the international community should include a health-workforce-specific benchmark in the framework for UHC and the post-2015 development agenda. The inclusion of HRH benchmarks in the post-2015 agenda could help to foster collaboration between countries and global partners and to focus policy actions and investments where they are most required.

The development of new benchmarks in the field of HRH should take into account several interrelated factors, including:

population growth and the demographic transition;

the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases and the corresponding changes in demand for health services by citizens;

the need to adapt the skills and competencies of health workers to match these changed demands;

an appreciation of health workforce challenges other than numerical shortages, and of the potential contributions of cadres other than physicians, nurses and midwives in improving health service availability and accessibility – especially in those disrupted health systems that face the most acute challenges;

the role of non-state actors, which has never been adequately captured in previous benchmarks or in the corresponding monitoring frameworks.

New benchmarks are required that give a better reflection of the diverse composition of the health workforce. They should take account of the contributions that are made by social workers who are involved in long-term care and by community health workers and mid-level health workers. The inclusion of these other cadres could result in targets that are realistically attainable even by low-income countries. Recent costing studies suggest that providing care through community health workers is affordable.25 However, any additions to the roles and expectations of health workers are likely to increase resource requirements.

Even adopting a more affordable skills mix and increasing efficiency in HRH spending through a renewed emphasis on performance and quality of care, the financial path towards UHC for some low-income countries and fragile states will inevitably involve, at least in the short-term, a role for official development assistance. Feng Zhao et al. discuss in an editorial in this theme issue how to maximize the returns of external financing for HRH.26

HRH benchmarks should influence the planning, management, support and monitoring of health systems. They should also be reflected in the setting of the targets used – at the national and global level – to track progress towards UHC and the health priorities of the post-2015 development agenda.

It would also be helpful, besides setting quantitative targets, to introduce an equity lens and explore needs in other dimensions, including the geographical distribution and sex composition of the health workforce. Minimum standards need to be established for all aspects of health worker performance – including responsiveness and competency and the associated management, financing and information systems. This round table base paper is complemented by four discussants,27–30 on how to strike the right balance between benchmarks that are sharp, actionable and measurable while simultaneously capturing the multifaceted nature and complexities of health workforce development.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Waage J, Banerji R, Campbell O, Chirwa E, Collender G, Dieltiens V, et al. The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015: Lancet and London International Development Centre Commission. Lancet. 2010;376:991–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe [Internet]. UN MDG report, 2012, stresses need for a true global partnership. Brussels: UNRICWE; 2012. Available from: http://www.unric.org/en/latest-un-buzz/27661-un-mdg-report-2012-stresses-need-for-a-true-global-partnership [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 3.Reidpath DD, Morel CM, Mecaskey JW, Allotey P. The Millennium Development Goals fail poor children: the case for equity-adjusted measures. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samb B, Evans T, Dybul M, Atun R, Moatti JP, Nishtar S, et al. World Health Organization Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet. 2009;373:2137–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA, et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet. 2004;364:900–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16987-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand S, Bärnighausen T. Health workers and vaccination coverage in developing countries: an econometric analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:1277–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand S, Bärnighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet. 2004;364:1603–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Human resources for health – overcoming the crisis Cambridge: Joint Learning Initiative; 2004. Available from: www.who.int/hrh/documents/JLi_hrh_report.pdf [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 9.The world health report 2006 – working together for health Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006 [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 10.Resolution WHA63.16. WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel. In: Sixty-third World Health Assembly, Geneva, 21 May 2010 Resolutions and decisions Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_R16-en.pdf [accessed 25 July 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit Leaders Declaration Toyako: Group of Eight; 2008. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/summit/2008/doc/doc080714__en.html [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 12.Global Health Workforce Alliance [Internet]. Reviewing progress, renewing commitment: launch of the progress report on the Kampala Declaration and Agenda for Global Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/forum/2011/progressreportlaunch [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 13.Building a future for women and children: the 2012 report Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/reports-and-articles/2012-report [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 14.Bossert TJ, Ono T. Finding affordable health workforce targets in low-income nations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1376–82. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD004015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Global Health Workforce Alliance [Internet]. Community health workers. Geneva: GHWA; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/themes/community [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 17.Lassi ZS, Cometto G, Huicho L, Bhutta ZA. Quality of care provided by mid-level health workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:824–33. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.118786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.One million community health workers [Internet]. Grant to help coordinate campaign to train one million community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa. New York: One Million Community Health Workers Campaign; 2013. Available from: http://www.1millionhealthworkers.org [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 19.Singh P, Sachs JD. 1 million community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa by 2015. Lancet. 2013;382:363–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response Geneva: The Sphere Project; 2011. Available from: http://www.sphereproject.org/resources/download-publications/?search=1&keywords=&language=English&category=22 [accessed 25 July 2013].

- 21.Resolution A. 67/L.36. Resolution on global health and foreign policy. In: Sixty-seventh session of the United Nations General Assembly, New York, 6 December 2012 New York: United Nations; 2012. Available from: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/67/L.36 [accessed 25 July 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolea C, Stormont L, Braichet JM. Evaluated strategies to increase attraction and retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:379–85. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.070607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The world health report 2010 – health systems financing: the path to universal coverage Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2010 [accessed 25 July 2013]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bhutta ZA, Chen L, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, et al. Education of health professionals for the 21st century: a global independent commission. Lancet. 2010;375:1137–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCord GC, Liu A, Singh P. Deployment of community health workers across rural sub-Saharan Africa: financial considerations and operational assumptions. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:244–53B. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao F, Squires N, Weakliam D, Van Lerberghe W, Soucat A, Toure K, et al. Investing in human resources for health: the need for a paradigm shift for the global health community over the next decade. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:799. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.118687. - [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boerma T, Siyam A. Health workforce indicators: let’s get real. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:886. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell J. Towards universal health coverage: a health workforce fit for purpose and practice. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:886. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126698. - [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheil-Adlung X. Health workforce benchmarks for universal health coverage and sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:888. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker BK. Empowering patients and strengthening communities for real health workforce and funding targets. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:889. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]