In many developed and developing countries, progress towards attaining UHC is hindered by the lack of a health workforce large enough and with the proper skills to deliver quality services to the entire population. Several factors accentuate the problems associated with health worker shortages, especially in low- and middle-income countries: maldistribution and migration of the workforce, inappropriate training, poor supervision, unregulated dual practice, imbalances in skill-mix composition, and reduced productivity and performance.1 Such problems are, however, not limited to low- and middle-income countries; many high-income countries are likely to face severe shortages of health workers because of budget cuts for social services resulting from the global economic downturn. The ageing of the population puts further pressure on health systems by increasing the demand for health care. Moreover, the changing dynamics of workforce migration, such as the increased exodus of workers from one developing country to another, pose a challenge for global health labour markets.2

Comprehensive health workforce policies

To address the challenges described and attain UHC, countries will have to develop effective policies to optimize the supply of health workers. This can only be accomplished through comprehensive planning of the health workforce based on an in-depth analysis of the health labour market to understand the driving forces affecting workforce supply and demand, both within countries and at the global level.

Partial health workforce policies designed on the basis of needs-based estimates and focused on training more health workers are not sufficient in addressing health worker shortages. The needs-based approach consists of estimating the number of health workers required to meet the needs of the population. Although these estimates are useful to inform the demand of health workers, they are not enough to formulate effective health workforce policies because they ignore the dynamics of the health labour market.3 Workforce shortages cannot be resolved by simply training more health workers; the health labour market conditions also have to be such that the newly-trained health workers can be absorbed into the health workforce. Otherwise, a fraction of them will migrate, work in another sector or remain unemployed and the resources spent on training them will have gone to waste.4

Health labour market dynamics are the main determinant of the level of employment in a country – not the health needs of the population or the education sector alone. The health labour market is influenced by the health needs of the population, the demand for health services and the supply and governance of health workers. Together these factors determine workers’ wages and allowances, the number of health workers employed, the number of hours they work, their geographical distribution, their employment settings, and their productivity and performance.5

The health labour market framework

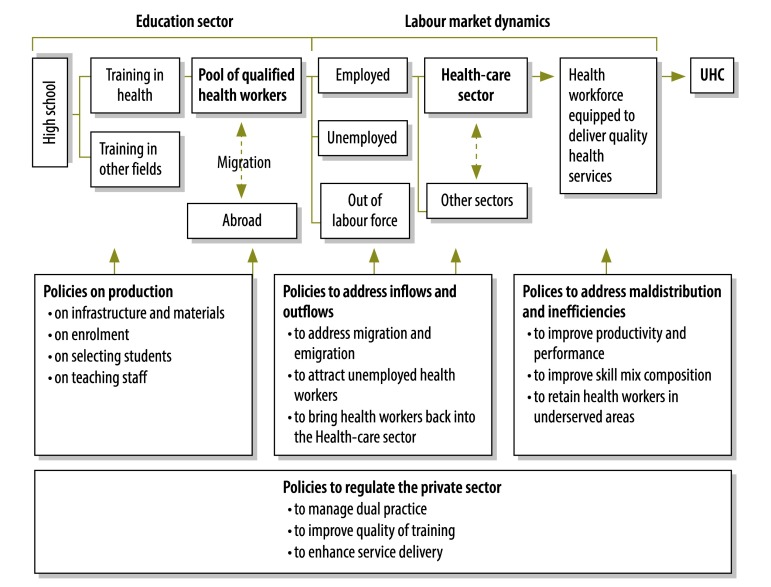

The framework presented in Fig. 1 provides a comprehensive picture of health labour market dynamics and of the contributions of four groups of health workforce policies to the attainment of equitable access to quality health services and UHC.

Fig. 1.

Health labour market framework and policy levers for attaining universal health coverage (UHC)

Note: The supply of health workers is made up of the pool of qualified health workers willing to work in the health-care sector. The demand for health workers is represented by the public and private institutions that constitute the health-care sector.

The training of health workers as defined by the education market is a key determinant of a country’s supply of new graduates – and hence of the supply of health labour. Production policies are those that pertain to the opening of new training institutions, the provision of scholarships, the offer of financial incentives for teaching staff, the alignment of health worker education with the health needs of the population, and the training of new cadres of health workers. These polices will succeed in producing enough health workers to fulfil the needs of the population only if they are designed in parallel with policies to ensure the absorption of new graduates into the labour market and to correct workforce maldistribution and inefficiencies.

The available supply of health workers – i.e. the number of qualified health workers willing to work for the health sector – is determined by wages, working conditions, safety and career opportunities. The demand for health-care workers is determined by the needs of the population and the demand for health services. Health worker demand is represented by those private and public institutions that are willing and able to pay for health workers to staff clinics, hospitals or other parts of the health system. These institutions compete with the each other by having different wage rates, budgets, provider payment practices, labour regulations and hiring rules that compete favourably with working conditions in other labour markets in attracting health professionals, including new graduates.8

The available supply of health workers is undermined by migration and by the attrition of those who choose to work outside the health sector. In Kenya, for example, 61% of physicians are not willing to work in their home country under current working conditions and wages and prefer to migrate to Australia, Namibia or the United States of America.9 Between 1990 and 2004, Zambia experienced a large exodus of physicians. To discourage physicians from leaving the country, the government increased their wages by 16% between 2007 and 2011 – to an amount 15 times the per capita income and in excess of the average pay received by other professionals with similar education, such as lawyers. Yet despite this increase, a physician’s average annual wage is only 21 780 United States dollars.10 Policies to attract health workers back to the health-care sector, discourage their migration and mobilize the unemployed, range from increasing wages and providing extra allowances to improving working conditions, revising recruitment strategies and offering training opportunities. If we are to draw closer to attaining equitable access to quality health services for the entire population, these policies will need to be designed with several factors in mind, including the geographical distribution of the current health workforce, worker productivity and performance, the skill-mix composition, and the allocation of health workers to the public and private sectors.

Although the shortage of health workers constrains service delivery, worker maldistribution, inappropriate training, poor supervision, low productivity and poor performance undermine the capacity of the existing supply of health workers to deliver quality services that are acceptable and accessible to the entire population. For example, Cameroon’s capital city of Yaoundé has 4.5 times as many health workers per inhabitant as the country’s poorest province.11 Such large health workforce inequalities stem from the low retention of health workers in poorer areas, which results in less access to health services and worse health outcomes in those areas than in more prosperous ones. Several policies are designed to redress worker maldistribution and inefficiencies. They include the training of local health workers; the opening of new vacancies; the adoption of recruitment strategies to increase the supply of health workers in underserved or rural areas; the provision of allowances; the granting of scholarships; and the matching of workers’ skills and tasks. UHC cannot be attained unless health workforce inefficiencies and resource wastage are eliminated by improving health worker productivity and performance.12

Virtually all countries have growing private health labour markets. Policies specifically designed to regulate the private sector need to be developed to ensure equitable access to quality health services for the entire population. In Sudan, for example, 90% of health workers engage in dual practice – i.e. they work in both the private and the public sector – but they do so informally, with little regulation. This jeopardizes the availability of health workers in the public sector and the quality of public health services.13 Staff training, service quality and dual practice are some of the areas in which regulatory policies are needed in the private health labour market.

Finally, the precise combination of health workforce policies intended to address worker shortages and maldistribution should be tailored to each country’s particular context and to its population’s health needs. In addition, innovative approaches such as task shifting and deployment of community health workers are needed to address inefficiencies and enhance equity in the delivery of services.

Conclusion

Health workforce policies that are partial rather than comprehensive, such as those that focus on education, are not effective in addressing health workforce shortages and ensuring equitable access to health services for a country’s entire population. A health labour market framework can provide the comprehensive approach needed to fully understand the forces behind health workforce supply and demand and make it possible to develop effective health workforce polices for the attainment of UHC.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.The world health report 2006: working together for health Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/ [accessed 11 September 2013].

- 2.WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/migration/code/WHO_global_code_of_practice_EN.pdf [accessed 11 September 2013].

- 3.Scheffler RM, Liu JX, Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR. Forecasting the global shortage of physicians: an economic- and needs-based approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:516–23B. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.046474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sousa A, Flores G. Transforming and scaling up health professional education: policy brief on financing education of health professionals. Geneva: Department for Health Systems Policies and Workforce, World Health Organization; 2013. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffler R, Bruckner T, Spetz J. The labour market for human resources for health in low and middle income countries Geneva: Department for Health Systems Policies and Workforce, World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/observer11/en/index.html [accessed 11 September 2013].

- 6.Vujicic M, Zurn P. The dynamics of the health labour market. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2006;21:101–15. doi: 10.1002/hpm.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vujicic M. Shedding light on the invisible hand – a labor market approach to health workforce policy Presented at the: Annual Session of the American Dental Association, San Francisco, 18–21 October 2012 Chicago: American Dental Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glassman A, Becker L, Makinen M, De Ferranti D. Planning and costing human resources for health. Lancet. 2008;371:693–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiambati H, Kiio CK, Toweett J. Understanding the labour market and productivity of human resources for health: country report Kenya. Geneva: Department for Health Systems Policies and Workforce, World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/tools/labour_market/en [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamwanga J, Koyi G, Mwila J, Musonda M, Bwalya R. Understanding the labour market and productivity of human resources for health: country report Zambia. Geneva: Department for Health Systems Policies and Workforce, World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/tools/labour_market/en [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ngah-Ngah S, Kingue S, Peyou MN, Bela AC. Understanding the labour market and productivity of human resources for health: country report Cameroon. Geneva: Department for Health Systems Policies and Workforce, World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/tools/labour_market/en [Google Scholar]

- 12.The world health report 2010 – health systems financing: the path to universal coverage Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/whr_background/en/ [accessed 11 September 2013]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Abu-Agla A, Ahmed N, Ahmed N, Badr E. Understanding the labour market and productivity of human resources for health: country report Sudan. Geneva: Department for Health Systems Policies and Workforce, World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/tools/labour_market/en [Google Scholar]