Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, “self-sufficiency in safe blood and blood products based on voluntary non-remunerated blood donation (VNRBD) means that the national needs of patients for safe blood and blood products, as assessed within the framework of the National Health Service (NHS), are met in a timely manner, that patients have equitable access to transfusion services and blood products, and that these products are obtained from VNRBD of national, and where needed, of regional origin, such as from neighbouring countries”1. In Italy, the achievement of self-sufficiency of plasma-derived medicinal products (PMPs), as well as blood components, is a goal of the blood system “aimed at guaranteeing equal conditions of quality and safety of transfusion therapy to all citizens”, as set out by the main regulatory reference2. Self-sufficiency is recognised as a role of “national, supra-regional, supra-local indivisible interest of the National Health Service” whose achievement is entrusted to the contributions of the regional health authorities. In order to attain this strategic goal, the Ministry of Health is responsible for defining an annual national programme for self-sufficiency aimed at identifying historical usages, real demand, necessary production levels, resources, funding system criteria, interregional PMP exchanges, import and export levels3–5. Moreover, according to current legislative provisions6,7, a special decree must be adopted for defining the “program for the development of plasma collection in blood services and blood collection units, as well as the promotion of an appropriate and rational use of plasma-derived medicinal products”.

In addition, national plasma derives from voluntary, periodic, responsible, anonymous and non-remunerated donations2. Regions and Autonomous Provinces (APs) (henceforth referred to as “Regions”), individually or in association, send the plasma collected by blood establishments (BE) to Kedrion Biopharma (Kedrion SpA, Castelvecchio Pascoli, Lucca, Italy), which, at the moment, is the only manufacturer authorised under a toll fractionation agreement. The latter has the capacity to produce at least the following PMPs: human albumin solution (albumin), polyvalent immunoglobulin (for intravascular administration, IVIG), plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates (pdFVIII), plasma-derived factor IX concentrates (pdFIX), prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), and antithrombin (AT). However, Regions remain owners of the plasma sent for fractionation, as well as of PMPs manufactured and of the residual raw material, including discards.

Therefore, self-sufficiency strongly depends on the capacity of regional health systems and the national blood system to ensure the satisfaction of patients’ needs using all products obtained by the manufacturing of national plasma within the toll fractionation agreements between Regions and fractionators thus reducing supplies from the pharmaceutical market8–10. However, also the appropriate clinical use of plasma11 and of PMPs plays a key role in self-sufficiency.

The aim of the present paper is to address the issue of PMPs self-sufficiency in Italy in 2011.

Information sources and definitions

All data related to plasma sent for fractionation and PMPs produced by Kedrion within the toll fractionation agreements, are provided by the aforementioned pharmaceutical company and constitute the information base for the analysis of national PMPs manufacturing. Data related to PMP demand are recorded by the Medicinal Products Traceability Flow (Flusso della Tracciabilità del Farmaco)12.

In 2011, for each PMP included in the agreements between Regions and Kedrion (albumin, IVIG, AT, pdFVIII, pdFIX, and PCCs), the self-sufficiency level achieved was assessed comparing the potential and effective supply, as well as the total and the NHS demand.

For the purpose of this paper, productive capacity (or potential supply) means the theoretic quantity of PMPs derivable from plasma sent to fractionation by each Region in the second half of 2010 and the first half of 2011. In contrast, effective supply (or toll fractionation) means the quantity of PMPs de facto distributed by Kedrion to each Region, during the 2011 calendar year. Data related to the productive capacity and effective supply are provided by Kedrion. Both productive capacity and effective supply are strictly influenced by the quantity and quality of plasma sent by Regions13, industrial yields and planning. However, effective supply is also influenced by product needs and requests, contractual duties, and product exchanges among those Regions in the same consortium/agreement. Small differences between these two sets of values can be partially attributed to the different period of time in which they have been calculated. Indeed, all PMPs distributed to Regions in the calendar year derive from the fractionation of plasma carried out during the first half of the same calendar year and the second half of the previous one.

Total demand refers to the regional PMP utilisation considering all distribution channels (public and private healthcare facilities, pharmacies, etc.). The NHS demand means the amount of total demand funded by the NHS.

Potential self-sufficiency means the per cent ratio between the productive capacity and the NHS demand. Effective self-sufficiency means the per cent ratio between the effective supply and the NHS demand. For the purposes of assessing the achieved self-sufficiency of each PMP at the national and regional levels, the value of effective self-sufficiency related to the regional self-sufficiency achievement was set at 90%.

Analysis of plasma sent for fractionation and supply of the toll factionation plasma medicinal products

Following the actions carried out by Regional Blood Services in conjunction with Blood Donor Associations and Federations, a constant growth in the quantity of national plasma collected was recorded over the last decade (Figure 1). Indeed, the quantity of plasma sent for fractionation was 462,805 kilograms (kg) in 2000 and 747,982 kg in 2011, recording a percentage increase of approximately 62%. The mean annual growth rate was 5.6% with two phases of higher growth (2004–2006 and 2008–2010). A negative variation (−1.1%) was recorded only in 2001.

Figure 1.

Quantity of plasma (kilograms) sent to industry by the Italian Blood System in the period 2000–2011.

Source: Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

In 2011, the quantities of different categories of plasma sent for fractionation by Italian Regions were, respectively: 188,523 kg (25%) of apheresis plasma (A-category), 455,922 kg (61%) of whole blood plasma (B-category), 102,998 kg of whole blood plasma (C-category), and 539 kg of anti-hepatitis B plasma (Table I). According to the agreements between Regions and Kedrion, plasma sent for fractionation is classified as follows: “A-category”, apheresis plasma frozen within 6 hours from its collection; “B-category”, whole blood plasma frozen within 7 hours from its collection; “C-category”, whole blood plasma frozen between 7 and 72 hours from its collection. With respect to these specifications, clotting factors can be obtained only from A- and B-category plasmas13.

Table I.

Quantity of plasma sent to industry in 2011 by each Regional Blood Transfusion Service according to the category (A, B or C) expressed in kilograms and percentage, year 2011.

Source: Kedrion, data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | A (kg) | % | B (kg) | % | C (kg) | % | Total kg 2011 | Total kg per 1,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 6,304.5 | 37% | 10,565.2 | 63% | 2.4 | 0% | 16,872.1 | 12.6 |

| Aosta Valley | 949.8 | 34% | 1,848.2 | 66% | 0.6 | 0% | 2,798.5 | 21.8 |

| AP Bolzano | 720.3 | 10% | 4,587.4 | 63% | 1,988.9 | 27% | 7,296.6 | 14.4 |

| AP Trento | 1,573.2 | 23% | 3,245.0 | 48% | 1,972.2 | 29% | 6,790.4 | 12.8 |

| Apulia | 7,231.3 | 20% | 23,199.4 | 64% | 5,799.4 | 16% | 36,230.1 | 8.9 |

| Basilicata | 1,830.8 | 28% | 3,365.5 | 52% | 1,246.9 | 19% | 6,443.2 | 11 |

| Calabria | 680.0 | 5% | 13,256.3 | 93% | 358.5 | 3% | 14,294.7 | 7.1 |

| Campania | 282.4 | 1% | 16,372.9 | 69% | 6,924.9 | 29% | 23,580.1 | 4 |

| ER | 22,472.5 | 28% | 47,210.0 | 58% | 11,273.8 | 14% | 80,956.3 | 18.3 |

| FVG | 9,454.9 | 34% | 11,790.8 | 42% | 6,838.1 | 24% | 28,083.8 | 22.7 |

| Latium | 2,383.2 | 8% | 27,594.9 | 88% | 1,257.7 | 4% | 31,235.8 | 5.5 |

| Liguria | 4,825.1 | 22% | 16,050.3 | 75% | 620.3 | 3% | 21,495.7 | 13.3 |

| Lombardy* | 41,066.4 | 28% | 83,926.2 | 58% | 19,841.1 | 14% | 145,260.3 | 14.6 |

| Marche | 10,909.6 | 39% | 16,335.8 | 58% | 924.0 | 3% | 28,169.4 | 18 |

| Molise | 695.9 | 21% | 2,616.1 | 79% | - | 0% | 3,312.0 | 10.4 |

| Piedmont* | 17,575.0 | 24% | 46,336.2 | 63% | 9,097.8 | 12% | 73,121.1 | 16.4 |

| Sardinia | 180.5 | 1% | 9,749.6 | 80% | 2,251.8 | 18% | 12,181.8 | 7.3 |

| Sicily | 7,217.3 | 16% | 36,159.4 | 80% | 1,913.3 | 4% | 45,290.0 | 9 |

| Tuscany | 27,645.7 | 40% | 41,349.8 | 60% | 5.3 | 0% | 69,000.8 | 18.4 |

| Umbria | 839.2 | 9% | 8,189.9 | 91% | - | 0% | 9,029.1 | 10 |

| Veneto | 23,677.0 | 27% | 32,069.2 | 37% | 30,358.8 | 35% | 86,105.0 | 17.4 |

| Army service | 8.7 | 2% | 104.0 | 24% | 322.2 | 74% | 434.9 | na |

|

| ||||||||

| Italy | 188,523.3 | 25% | 455,921.9 | 61% | 102,997.6 | 14% | 747,981.6 | 12.3 |

Legend A: A-category plasma; plasma from apheresis frozen within 6 hours from its collection; B: B-category plasma; whole blood plasma frozen within 7 hours from its collection; C: C-category plasma; whole blood plasma frozen between 7 and 72 hours from its collection; kg: kilogram; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia;

Lombardy and Piedmont conferred 426.6 and 112.2 kilograms of anti-hepatitis B plasma, respectively;

na: not assessable.

Although interregional agreements are aimed at optimising plasma batches and frequency of PMPs distribution, improving plasma products yields, and reducing manufacture costs, a wide variability was observed as regards the quantity (and quality - data not shown) of plasma sent for fractionation by Regions.

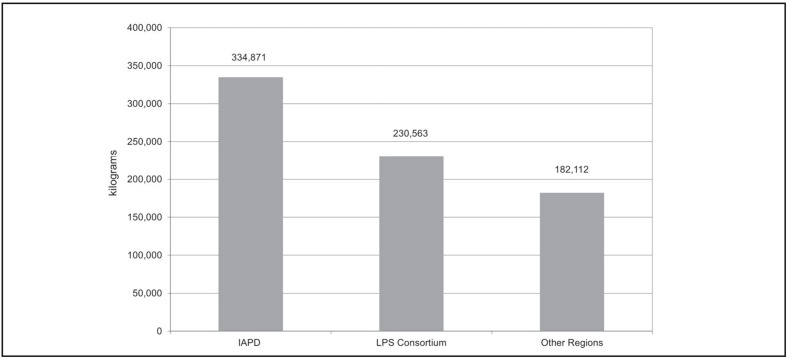

The Interregional Agreement on Plasma-Derivation (IAPD) is the main interregional agreement and includes Veneto (leader Region), Abruzzo, Aosta Valley, APs of Bolzano and Trento, Basilicata, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Tuscany and Umbria. Together with the Consortium Lombardy-Piedmont-Sardinia (LPS) (leader Region: Lombardy), they involve 14 Regions and collect approximately three-quarters (75.6%) of the total plasma sent for fractionation. In 2011, the IAPD sent 334,871 kg, the LPS 230,563 kg, and the remaining non-consortium Regions 182,112 kg (Figure 2) representing 45%, 31%, and 24% of national total plasma sent for fractionation, respectively. In addition, 435 kg of plasma were collected by the Army blood transfusion service (Table I) that cooperates with the NHS facilities, the Ministry of the Interior and the Department of Civil Protection in order to ensure the maintenance of adequate supplies for potential emergency situations2. There was also a wide variation in the regional percentages of different plasma categories sent for industrial fractionation, probably ascribable to different organizational models for apheresis plasma collection and/or higher clinical use of apheresis plasma. The highest percentages of apheresis plasma were recorded in Tuscany (40%), Marche (39%), and Abruzzo (37%) while Campania, Sardinia, and Calabria did not send significant amounts of A-category plasma (<5%). As far as B-category plasma is concerned, the highest percentage contributions were recorded in Calabria (93%), Umbria (91%), and Latium (88%) and the lowest percentage was recorded in Veneto (37%) (Table I).

Figure 2.

Quantity of plasma (kilograms) sent to industry by two main consortia of Italian Regions and by the other remaining non-consortium Regions in 2011.

Source: Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

Legend IAPD: Interregional Agreement on Plasma-Derivation; LPS: Lombardy-Piedmont-Sardinia.

If the quantities of plasma for fractionation are standardised per resident population, in 2011 the IAPD sent 16.8 kg per 1,000 population, the LPS 14.4 kg per 1,000 population, and the remaining Regions 7.4 kg per 1,000 population (Figure 3). The national mean value was 12.3 kg per 1,000 population with significantly different contributions by each Region (Figure 4). Indeed, maximum values of 22.7 kg per 1,000 population were recorded in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, 21.8 in Aosta Valley and 18.4 in Tuscany. Minimum contributions derived from demographically important Regions such as Latium and Campania, with 5.5 and 4 kg per 1,000 population, respectively.

Figure 3.

Quantity of plasma (kilograms per 1,000 population) sent to industry by two main consortia of Italian Regions and by the other remaining non-consortium Regions in 2011.

Source: Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

Legend IAPD: Interregional Agreement on Plasma-Derivation; LPS: Lombardy-Piedmont-Sardinia.

Figure 4.

Plasma for fractionation sent to industry (kilograms per 1,000 population) at regional and national level in 2011.

Source: Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

Legend FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia; ER: Emilia-Romagna; AP: Autonomous Province.

Table II shows the quantity of plasma (kg) sent to industry during the second half of 2010 and the first half of 2011 by Regional Blood Transfusion Services and the total amount of PMPs potentially derivable in 2011, expressed in grams or International Units (I.U.), according to the yields declared by Kedrion (productive capacity).

Table II.

Quantity of plasma (kilograms) sent to industry during the second half of 2010 and the first half of 2011 by Regional Blood Transfusion Services and plasma medicinal products productive capacity in 2011 (grams or international units)

Source: Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | 2nd semester 2010 (kg) | 1st semester 2011 (kg) | Total kg | Albumin (g) | IVIG (g) | pdFVIII (I.U.) | pdFIX/PCCs (I.U.) | AT (I.U.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 7,617.1 | 8,014.8 | 15,631.9 | 393,923 | 56,275 | 2,062,596 | 2,859,508 | 2,343,859 |

| Aosta Valley | 1,342.8 | 1,470 | 2,812.7 | 70,881 | 10,126 | 371,208 | 514,629 | 421,827 |

| AP Bolzano | 3,290.2 | 3,603.7 | 6,893.9 | 173,726 | 24,818 | 909,996 | 1,261,585 | 1,034,086 |

| AP Trento | 3,151.7 | 3,395.5 | 6,547.2 | 164,988 | 23,570 | 864,225 | 1,198,131 | 982,074 |

| Apulia | 18,256.4 | 17,646.8 | 35,903.2 | 904,760 | 129,251 | 4,019,190 | 5,572,059 | 4,567,261 |

| Basilicata | 3,286.9 | 2,982 | 6,268.9 | 157,976 | 22,568 | 677,001 | 938,569 | 769,319 |

| Calabria | 6,927.7 | 7,012.2 | 13,939.9 | 351,285 | 50,184 | 1,806,867 | 2,504,975 | 2,053,258 |

| Campania | 10,683.1 | 11,822.2 | 22,505.3 | 567,134 | 81,019 | 2,004,108 | 2,778,422 | 2,277,395 |

| ER | 39,748.9 | 40,171.4 | 79,920.3 | 2,013,992 | 287,713 | 8,969,980 | 12,435,655 | 10,193,160 |

| FVG | 14,126.4 | 14,603.3 | 28,729.7 | 723,989 | 103,427 | 3,510,867 | 4,867,339 | 3,989,622 |

| Latium | 13,599,6 | 14,793,1 | 28,392,8 | 715,498 | 102,214 | 3,571,763 | 4,951,762 | 4,058,821 |

| Liguria | 11,215.4 | 9,289.8 | 20,505.2 | 516,731 | 73,819 | 2,641,563 | 3,662,167 | 3,001,777 |

| Lombardy | 70,997.2 | 71,704.2 | 142,701.3 | 3,596,074 | 513,725 | 16,256,624 | 22,537,592 | 18,473,436 |

| Marche | 15,489.1 | 13,486.6 | 28,975.6 | 730,186 | 104,312 | 3,670,638 | 5,088,839 | 4,171,179 |

| Molise | 1,592.9 | 1,655.5 | 3,248.4 | 81,860 | 11,694 | 428,791 | 594,461 | 487,263 |

| Piedmont | 35,839.2 | 36,331.2 | 72,170.4 | 1,818,694 | 259,813 | 8,388,522 | 11,629,542 | 9,532,412 |

| Sardinia | 5,738.8 | 7,043.2 | 12782 | 322,106 | 46,015 | 1,343,187 | 1,862,146 | 1,526,349 |

| Sicily | 22,439.1 | 21,654.3 | 44,093.4 | 1,111,153 | 158,736 | 5,347,087 | 7,413,006 | 6,076,235 |

| Tuscany | 33,821.6 | 33,652.5 | 67,474.1 | 1,700,348 | 242,907 | 8,906,583 | 12,347,763 | 10,121,118 |

| Umbria | 4,607.5 | 4,301.4 | 8,908.9 | 224,504 | 32,072 | 1,175,974 | 1,630,328 | 1,336,334 |

| Veneto | 42,641 | 43,205.8 | 85,846.9 | 2,163,341 | 309,049 | 10,599,248 | 14,694,412 | 12,044,600 |

| Army services | 127.1 | 247 | 374.2 | 9,429 | 1,347 | 12,513 | 17,348 | 14,220 |

|

| ||||||||

| Italy | 366,539.7 | 368,086.4 | 734,626.1 | 18,512,577 | 2,644,654 | 87,538,532 | 121,360,237 | 99,475,604 |

Legend kg: kilogram; g: gram; I.U.: international unit; IVIG: polyvalent immunoglobulins for intravenous administration; pdFVIII: plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates; pd FIX: plasma-derived factor IX concentrates; PCCs: protrombin complex concentrates; AT: antitrombin; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

The industrial yields for albumin and IVIG are approximately 25.2 and 3.6 grams (g) per kg of plasma, respectively, regardless of plasma category. On the contrary, the yields for pdFVIII, pdFIX, PCCs and AT are significantly influenced by the quality of plasma sent to fractionation by each Regional Blood Transfusion Service.

Table III shows the quantities in grams or I.U. of the six PMPs included in the regional toll fractionation agreements between Kedrion and Regions and returned to Regions in 2011 (effective supply or toll fractionation).

Table III.

Effective supply (grams or international units) of plasma medicinal products included in the regional toll fractionation agreements between Kedrion and Regions, year 2011.

Source: Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | Albumin (g) | IVIG (g) | pdFVIII (I.U.) | pdFIX (I.U.) | PCCs (I.U.) | AT (I.U.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 350,500 | 49,000 | 44,000 | 26,000 | 166,500 | 2,011,000 |

| Aosta Valley | 74,000 | 8,600 | 147,000 | - | 225,000 | 125,000 |

| AP Bolzano | 113,000 | 29,780 | 360,000 | 125,000 | 553,500 | 400,000 |

| AP Trento | 105,000 | 20,160 | - | - | 162,500 | 75,000 |

| Apulia | 744,610 | 97,580 | 2,799,000 | - | 1,150,000 | 3,052,000 |

| Basilicata | 261,500 | 18,720 | 22,000 | 15,000 | 218,500 | 1,675,000 |

| Calabria | 307,860 | 57,280 | 657,000 | 49,000 | 102,500 | 1,500,000 |

| Campania | 488,040 | 69,870 | 965,000 | - | 800,000 | 5,604,000 |

| ER | 1,828,500 | 235,693 | 2,175,000 | 625,000 | 3,228,500 | 1,402,000 |

| FVG | 320,000 | 76,280 | 808,000 | 225,000 | 500,000 | 3,250,000 |

| Latium | 587,380 | 96,130 | 4,083,000 | 536,000 | 1,148,000 | 3,398,000 |

| Liguria | 700,000 | 113,535 | 835,000 | 370,000 | 560,000 | 4,554,000 |

| Lombardy | 3,146,290 | 482,425 | 12,250,500 | 1,426,500 | 3,885,500 | 4,917,000 |

| Marche | 467,910 | 104,965 | 2,029,000 | 381,000 | 1,132,500 | 2,150,000 |

| Molise | 58,050 | 13,465 | 50,000 | - | 100,000 | 300,000 |

| Piedmont | 1,277,500 | 244,650 | 7,656,000 | 2,006,500 | 1,254,000 | 9,891,000 |

| Sardinia | 417,500 | 47,470 | 216,000 | - | 715,000 | 3,590,000 |

| Sicily | 1,234,870 | 121,840 | 1,953,000 | 167,000 | 1,186,000 | 9,623,000 |

| Tuscany | 2,117,250 | 278,265 | 4,690,000 | 558,000 | 2,288,000 | 8,844,000 |

| Umbria | 455,000 | 60,105 | 251,000 | 12,000 | 400,000 | 701,000 |

| Veneto | 1,797,500 | 315,415 | 4,178,000 | 1,098,000 | 2,068,000 | 7,455,000 |

| Army services | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Italy | 16,852,260 | 2,541,228 | 46,168,500 | 7,620,000 | 21,844,000 | 74,517,000 |

Legend g: grams; IVIG: polyvalent immunoglobulin for intravenous use; pdFVIII: plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates; I.U.: international unit; pdFIX: plasma-derived factor IX concentrates; PCCs: prothrombin complex concentrates; AT: antithrombin; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

Self-sufficiency analysis

Human albumin solution

In 2011, the NHS demand accounted for 84% of albumin total demand14. The national potential self-sufficiency was 60%, whereas the effective one was barely 55% (Table IV). The effective self-sufficiency (≥90%) was achieved in Aosta Valley, APs of Trento and Bolzano, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Marche, Tuscany, Umbria, and Veneto. With the exception of Marche, all aforementioned Regions are members of the IAPD. Umbria (effective self-sufficiency 99% vs potential self-sufficiency 49%), Basilicata (77% vs 47%), and Liguria (92% vs 68%) mainly benefited from the interregional exchanges within the IAPD. Conversely, Apulia, Calabria, Latium, and Sardinia with percentages between 21% and 23% were far from achieving effective self-sufficiency; Campania barely covered 15% of NHS demand with the effective supply.

Table IV.

Estimates of national and regional human albumin self-sufficiency, year 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | Total demand (g) | NHS demand (g) | Productive capacity (g) | Effective supply (g) | Potential self-sufficiency (%) | Effective self-sufficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 802,783 | 666,798 | 393,923 | 350,500 | 59% | 53% |

| Aosta Valley | 74,480 | 74,480 | 70,881 | 74,000 | 95% | 99% |

| AP Bolzano | 116,570 | 116,440 | 173,726 | 113,000 | 149% | 97% |

| AP Trento | 123,475 | 110,530 | 164,988 | 105,000 | 149% | 95% |

| Apulia | 3,762,990 | 3,322,238 | 904,760 | 744,610 | 27% | 22% |

| Basilicata | 354,735 | 338,903 | 157,976 | 261,500 | 47% | 77% |

| Calabria | 1,466,588 | 1,345,648 | 351,285 | 307,860 | 26% | 23% |

| Campania | 4,328,273 | 3,226,335 | 567,134 | 488,040 | 18% | 15% |

| ER | 2,254,210 | 1,946,500 | 2,013,992 | 1,828,500 | 103% | 94% |

| FVG | 340,380 | 330,135 | 723,989 | 320,000 | 219% | 97% |

| Latium | 4,036,993 | 2,863,000 | 715,498 | 587,380 | 25% | 21% |

| Liguria | 806,700 | 759,058 | 516,731 | 700,000 | 68% | 92% |

| Lombardy | 5,517,158 | 4,281,590 | 3,596,074 | 3,146,290 | 84% | 73% |

| Marche | 571,033 | 505,065 | 730,186 | 467,910 | 145% | 93% |

| Molise | 191,583 | 146,670 | 81,860 | 58,050 | 56% | 40% |

| Piedmont | 1,659,628 | 1,437,240 | 1,818,694 | 1,277,500 | 127% | 89% |

| Sardinia | 2,046,890 | 2,015,680 | 322,106 | 417,500 | 16% | 21% |

| Sicily | 2,929,808 | 2,449,470 | 1,111,153 | 1,234,870 | 45% | 50% |

| Tuscany | 2,493,200 | 2,344,098 | 1,700,348 | 2,117,250 | 73% | 90% |

| Umbria | 464,650 | 461,763 | 224,504 | 455,000 | 49% | 99% |

| Veneto | 2,029,680 | 1,839,743 | 2,163,341 | 1,797,500 | 118% | 98% |

| Other* | 70,858 | 105,928° | 9,429 | na | na | |

|

| ||||||

| Italy | 36,442,660 | 30,687,308 | 18,512,577 | 16,852,260 | 60% | 55% |

Legend g: grams; NHS: National Health Service; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia; Other*: movements of medicinal products not univocally defined;

the National Health Service demand can appear bigger than total demand on the basis of the fact that the former considers all movements related to the National Health Service expenditure recorded in medicinal products traceability that are tied to intermediate recipients (warehousemen, wholesalers, etc.), which are not envisaged in the total demand. The latter takes into account just the final users’ consumptions. In order to calculate self-sufficiency in the worst scenario, it was preferred to always consider the biggest value.

If regional consortia are compared, the IAPD recorded an effective supply similar to the productive capacity with a per cent ratio of 98%; the latter was 85% for the LPS, and 87% for the remaining Regions.

The above data seem to reflect a better organizational efficiency of the IAPD. In fact, in terms of effective self-sufficiency, the IADP covered the NHS demand with a mean percentage of 90% compared to 63% of the LPS and 28% of the remaining non-consortium Regions. The Marche Region had an unusual situation, recording an excess of albumin (about 262 kg), which was not made available to other Regions.

As albumin is considered a driving product (i.e. a PMP whose trends related to both demand and supply involve significant variations within the overall market), a joint distribution analysis of the productive capacity (grams per 1,000 population) and NHS demand (grams per 1,000 population) at regional level was carried out. Figure 5 shows the position of all Italian Regions with respect to albumin productive capacity and utilisation both related to the national mean values, which are highlighted by the secondary axes.

Figure 5.

Regional joint distribution according to standardised albumin productive capacity (grams per 1,000 population) and standardised National Health Service demand (grams per 1,000 population) in 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

Legend FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia; ER: Emilia-Romagna; AP: Autonomous Province; NHS: National Health Service.

The low rate of potential self-sufficiency in Sardinia, Apulia, Calabria, and Campania is a consequence of very high (and probably inappropriate) usage in comparison to the national average as well as low collection of plasma for fractionation. On the contrary, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Marche showed the highest potential self-sufficiency per 1,000 population.

Polyvalent immunoglobulin for intravenous administration

In 2011, the NHS demand of IVIG accounted for 96% of total demand15. National effective self-sufficiency was 81%, similar to the potential one (83%) (Table V). Basilicata, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Lombardy, Marche, Molise, and Veneto achieved effective self-sufficiency (≥90%). Umbria (effective self-sufficiency 88% and potential self-sufficiency 47%) and Liguria (effective self-sufficiency 90% and potential self-sufficiency 58%) mainly benefited from the interregional exchange agreements. Campania (43%), Latium (48%), Apulia, and Sardinia (both 56%) were far from achieving effective self-sufficiency.

Table V.

Estimates of national and regional self-sufficiency in polyvalent immunoglobulin for intravenous administration in 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | Total demand (g) | NHS demand (g) | Productive capacity (g) | Effective supply (g) | Potential self-sufficiency (%) | Effective self-sufficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 70,793 | 70,768 | 56,275 | 49,000 | 80% | 69% |

| Aosta Valley | 11,843 | 11,843 | 10,126 | 8,600 | 86% | 73% |

| AP Bolzano | 35,829 | 35,829 | 24,818 | 29,780 | 69% | 83% |

| AP Trento | 22,740 | 22,740 | 23,570 | 20,160 | 104% | 89% |

| Apulia | 194,847 | 175,257 | 129,251 | 97,580 | 74% | 56% |

| Basilicata | 19,964 | 19,964 | 22,568 | 18,720 | 113% | 94% |

| Calabria | 84,301 | 84,301 | 50,184 | 57,280 | 60% | 68% |

| Campania | 165,094 | 160,817 | 81,019 | 69,870 | 50% | 43% |

| ER | 251,585 | 251,350 | 287,713 | 235,693 | 114% | 94% |

| FVG | 80,653 | 80,803° | 103,427 | 76,280 | 128% | 94% |

| Latium | 249,788 | 201,225 | 102,214 | 96,130 | 51% | 48% |

| Liguria | 126,676 | 126,567 | 73,819 | 113,535 | 58% | 90% |

| Lombardy | 576,666 | 526,132 | 513,725 | 482,425 | 98% | 92% |

| Marche | 117,283 | 117,173 | 104,312 | 104,965 | 89% | 90% |

| Molise | 21,950 | 14,575 | 11,694 | 13,465 | 80% | 92% |

| Piedmont | 306,901 | 303,691 | 259,813 | 244,650 | 86% | 81% |

| Sardinia | 84,439 | 84,364 | 46,015 | 47,470 | 55% | 56% |

| Sicily | 200,402 | 196,677 | 158,736 | 121,840 | 81% | 62% |

| Tuscany | 432,952 | 432,414 | 242,907 | 278,265 | 56% | 64% |

| Umbria | 67,955 | 67,955 | 32,072 | 60,105 | 47% | 88% |

| Veneto | 335,054 | 331,809 | 309,049 | 315,415 | 93% | 95% |

| Other* | 83 | - | 1,347 | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Italy | 3,457,793 | 3,316,251 | 2,644,654 | 2,541,228 | 83% | 81% |

Legend g: grams; NHS: National Health Service; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia;

the National Health Service demand can appear bigger than total demand on the basis of the fact that the former considers all movements related to the National Health Service expenditure recorded in medicinal products traceability that are tied to intermediate recipients (warehousemen, wholesalers, etc.), which are not envisaged in the total demand. The latter takes into account just the final users’ consumptions. In order to calculate self-sufficiency in the worst scenario, it was preferred to always consider the biggest value.

Other*: movements of medicinal products not univocally defined.

If regional aggregations are compared, the IAPD recorded a mean effective self-sufficiency of 83%, the LPS achieved 85% and the remaining Regions 61%.

As also IVIG is considered a driving product, a joint distribution analysis of the productive capacity (grams per 1,000 population) and NHS demand (grams per 1,000 population) at regional level was carried out. Figure 6 shows the position of all Italian Regions with respect to IVIG productive capacity and utilisation both related to the national mean values, which are highlighted by the secondary axes. It shows that, although several Regions (upper right quadrant of the graph) recorded high productive capacity levels compared to the national mean value, their potential self-sufficiency level was low due to very high usage.

Figure 6.

Regional joint distribution according to standardised polyvalent immunoglobulin for intravenous administration productive capacity (grams per 1,000 population) and standardised National Health Service demand (grams per 1,000 population) in 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

Legend FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia; ER: Emilia-Romagna; AP: Autonomous Province; NHS: National Health Service.

In order to achieve self-sufficiency, IVIG demand should be thoroughly analysed in terms of appropriateness and management of interregional exchanges.

Antithrombin

In 2011, the NHS demand for AT was almost mirrored by the total demand at national level (94%)16. The effective self-sufficiency level was significantly lower than the potential one (65% vs 86%) (Table VI). Abruzzo, Aosta Valley, APs of Trento and Bolzano, Basilicata, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Marche, Piedmont, Umbria, and Veneto achieved effective self-sufficiency (≥90%). Basilicata (effective self-sufficiency 93% vs potential self-sufficiency 43%) and Liguria (100% vs 66%) mainly benefited from the interregional exchange agreements. On the contrary, Apulia, Calabria, Campania, Latium, and Molise, with percentages between 23% and 47%, were far from achieving effective self-sufficiency. It is important to underline that Tuscany achieved an effective self-sufficiency level lower than the potential one (88% vs 101%) buying approximately one million of I.U. of AT from the market. In contrast, Sicily achieved an effective self-sufficiency (66%), despite its low productive capacity (42%), thanks to the availability of the AT intermediate product given by IAPD jointly with Tuscany (Table VI).

Table VI.

Estimates of national and regional antithrombin self-sufficiency in 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | Total demand (I.U.) | NHS demand (I.U.) | Productive capacity (I.U.) | Effective supply (I.U.) | Potential self-sufficiency (%) | Effective self-sufficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 2,149,500 | 2,146,000 | 2,343,859 | 2,011,000 | 109% | 94% |

| Aosta Valley | 130,000 | 130,000 | 421,827 | 125,000 | 324% | 96% |

| AP Bolzano | 400,000 | 400,000 | 1,034,086 | 400,000 | 259% | 100% |

| AP Trento | 77,000 | 75,000 | 982,074 | 75,000 | 1,309% | 100% |

| Apulia | 7,387,500 | 6,717,000 | 4,567,261 | 3,052,000 | 68% | 45% |

| Basilicata | 1,805,500 | 1,805,500 | 769,319 | 1,675,000 | 43% | 93% |

| Calabria | 5,996,500 | 5,570,500 | 2,053,258 | 1,500,000 | 37% | 27% |

| Campania | 17,222,500 | 16,398,500 | 2,277,395 | 5,604,000 | 14% | 34% |

| ER | 2,031,000 | 1,408,000 | 10,193,160 | 1,402,000 | 724% | 100% |

| FVG | 3,250,000 | 3,250,000 | 3,989,622 | 3,250,000 | 123% | 100% |

| Latium | 16,017,000 | 14,771,500 | 4,058,821 | 3,398,000 | 27% | 23% |

| Liguria | 4,911,000 | 4,554,000 | 3,001,777 | 4,554,000 | 66% | 100% |

| Lombardy | 9,169,000 | 6,709,500 | 18,473,436 | 4,917,000 | 275% | 73% |

| Marche | 2,160,000 | 2,160,000 | 4,171,179 | 2,150,000 | 193% | 100% |

| Molise | 983,500 | 643,000 | 487,263 | 300,000 | 76% | 47% |

| Piedmont | 11,059,500 | 10,633,000 | 9,532,412 | 9,891,000 | 90% | 93% |

| Sardinia | 5,303,000 | 5,301,500 | 1,526,349 | 3,590,000 | 29% | 68% |

| Sicily | 14,978,000 | 14,522,500 | 6,076,235 | 9,623,000 | 42% | 66% |

| Tuscany | 10,064,000 | 10,062,500 | 10,121,118 | 8,844,000 | 101% | 88% |

| Umbria | 701,000 | 701,000 | 1,336,334 | 701,000 | 191% | 100% |

| Veneto | 7,524,000 | 7,455,000 | 12,044,600 | 7,455,000 | 162% | 100% |

| Other* | 10,000 | 44,500* | 14,220 | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Italy | 123,329,500 | 115,458,500 | 99,475,604 | 74,517,000 | 86% | 65% |

Legend I.U.: international unit; NHS: National Health Service; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia; Other*: movements of medicinal products not univocally defined.

In order to use all unexpressed potentialities, these gaps could be reduced by the adoption of more incisive interregional exchange mechanisms, more efficient management and planning of the industrial manufacturing as well as a more appropriate clinical use of this PMP whose evidence based clinical indications, especially for acquired deficiencies, are still very limited16.

Plasma-derived factor VIII

In order to estimate the pdFVIII self-sufficiency in 2011, the demand of PMPs containing pdFVIII was taken into account, independently from the von Willebrand Factor (vWF) content and the potential additional indication for von Willebrand Disease (vWD).

For the purpose of analysing the pdFVIII demand and supply, consideration should be given to the fact that the choice of the medicinal product for haemophilia A treatment is made according to an evaluation of safety and tolerability and to clinical decisions that are taken within the “therapeutic alliance” between patient and physician. Moreover, all clinical considerations and decisions have to be safeguarded and do not necessarily allow for substitutability in medical prescription17–20. In fact, although the published evidence regarding the development of inhibitors in response to product switching does not support that switching factor concentrate in previously treated haemophilia patients will significantly influence the development of clinically relevant inhibitors, we should be aware that “absence of evidence for a risk of inhibitor is not the same as evidence of no risk”21.

In 2011, the pdFVIII total demand22 was not entirely satisfied by the only toll fractionation-derived product, the Emoclot® manufactured by Kedrion (Table VII). WHEREAS, the specific demand for Emoclot® was entirely met by the Emoclot® supplied by toll fractionation. In this case the productive capacity and effective supply of Emoclot® are equivalent. In fact, the latter is defined within the toll fractionation agreements, reaching sufficient quantities to meet the specific demand and producing a surplus. Indeed, the manufacturer finalised the process to obtain finished products from the intermediate ones, according to the existing contracts.

Table VII.

Estimates of national and regional plasma-derived factor VIII self-sufficiency in 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | Total demand (I.U.) | NHS demand (I.U.) | Productive capacity (I.U.) | Effective offer (I.U.) | Potential self-sufficiency (%) | Effective self-sufficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 276,000 | 276,000 | 2,062,596 | 44,000 | 747% | 16% |

| Aosta Valley | 147,000 | 147,000 | 371,208 | 147,000 | 253% | 100% |

| AP Bolzano | 1,140,000 | 1,140,000 | 909,996 | 360,000 | 80% | 32% |

| AP Trento | 125,000 | 125,000 | 864,225 | - | 691% | 0% |

| Apulia | 6,318,000 | 6,296,000 | 4,019,190 | 2,799,000 | 64% | 44% |

| Basilicata | 22,000 | 22,000 | 677,001 | 22,000 | 3,077% | 100% |

| Calabria | 2,583,500 | 1,199,500 | 1,806,867 | 657,000 | 151% | 55% |

| Campania | 6,911,000 | 6,482,000 | 2,004,108 | 965,000 | 31% | 15% |

| ER | 4,756,500 | 4,281,500 | 8,969,980 | 2,175,000 | 210% | 51% |

| FVG | 986,000 | 986,000 | 3,510,867 | 808,000 | 356% | 82% |

| Latium | 12,518,500 | 5,570,000 | 3,571,763 | 4,083,000 | 64% | 73% |

| Liguria | 1,916,000 | 1,825,000 | 2,641,563 | 835,000 | 145% | 46% |

| Lombardy | 21,935,500 | 23,905,500° | 16,256,624 | 12,250,500 | 68% | 51% |

| Marche | 2,261,000 | 2,261,000 | 3,670,638 | 2,029,000 | 162% | 90% |

| Molise | 317,000 | 99,000 | 428,791 | 50,000 | 433% | 51% |

| Piedmont | 10,323,500 | 10,271,500 | 8,388,522 | 7,656,000 | 82% | 75% |

| Sardinia | 360,000 | 360,000 | 1,343,187 | 216,000 | 373% | 60% |

| Sicily | 5,259,500 | 5,307,500° | 5,347,087 | 1,953,000 | 101% | 37% |

| Tuscany | 8,465,000 | 8,474,000° | 8,906,583 | 4,690,000 | 105% | 55% |

| Umbria | 315,000 | 315,000 | 1,175,974 | 251,000 | 373% | 80% |

| Veneto | 4,692,000 | 4,538,000 | 10,599,248 | 4,178,000 | 234% | 92% |

| Other* | 300,500 | 2,532,500° | 12,513 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Italy | 91,928,500 | 86,414,000 | 87,538,532 | 46,168,500 | 101% | 53% |

Legend I.U.: international unit; NHS: National Health Service; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia; Other*: movements of medicinal products not univocally defined;

the National Health Service demand can appear bigger than total demand on the basis of the fact that the former considers all movements related to the National Health Service expenditure recorded in medicinal products traceability that are tied to intermediate recipients (warehousemen, wholesalers, etc.), which are not envisaged in the total demand. The latter takes into account just the final users’ consumptions. In order to calculate self-sufficiency in the worst scenario, it was preferred to always consider the biggest value.

All these elements can explain why the level of effective supply was lower than the level of the productive capacity and the level of effective self-sufficiency achieved was less than 100% in several Regions (Table VII). Moreover, Emoclot® is not indicated for the vWD treatment, even if its content of vWF is standardised.

If all products containing pdFVIII are considered, in 2011, the NHS demand is almost mirrored by the total demand (94%). The potential self-sufficiency was 101% and the effective one was 53%, with a regional variable range from 0 to 100% (Table VII). According to toll fractionation agreements, the pdFVIII distributed to Regions covered slightly more than half the pdFVIII demand.

Though respecting both the above-mentioned principles of haemophilia A treatment and the indications/characteristics of the Kedrion medicinal product, the use of Emoclot™ should be encouraged in order to meet the total demand for factor VIII, with particular regard to pdFVIII, and to reduce its surplus, thus increasing the efficacy of regional toll fractionation agreements.

Plasma-derived factor IX and prothrombin complex concentrates

The industrial production of pdFIX and PCCs are mutually exclusive (one excludes the other) and, for this reason, self-sufficiency is jointly analysed23.

Considerations made for pdFVIII apply also to pdFIX in relation to the principle of non-necessary substitutability among proprietary medicinal products, within the medical prescription (principle of “continuity of therapeutic healthcare”).

In 2011, the NHS demand of pdFIX and PCCs was 93% of total demand (Table VIII)22,24. The potential and effective self-sufficiency were 347% and 84%, respectively. Therefore, self-sufficiency for both PMPs can be considered achieved at the national level. However, regional effective self-sufficiency varied from 19% to 100% showing some critical aspects with regard to planning, transfer mechanisms and interregional exchanges. In particular, the Regions of Abruzzo (effective self-sufficiency of 19%), Apulia (38%), Calabria (45%), Campania (60%), Molise (54%), Sardinia (83%), and Umbria (79%) significantly supplied from the market, despite their productive capacity was 2 or 3 times higher than their own NHS demand.

Table VIII.

Estimates of national and regional prothrombin complex concentrates and plasma-derived factor IX self-sufficiency in 2011.

Source: medicinal products traceability and Kedrion data processed and adapted by the Italian National Blood Centre.

| Region | Total demand (I.U.) | NHS demand (I.U.) | Productive capacity (I.U.) | Effective supply (I.U.) | Potential self-sufficiency (%) | Effective self-sufficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | 996,900 | 996,900 | 2,859,508 | 192,500 | 287% | 19% |

| Aosta Valley | 225,000 | 225,000 | 514,629 | 225,000 | 229% | 100% |

| AP Bolzano | 678,500 | 678,500 | 1,261,585 | 678,500 | 186% | 100% |

| AP Trento | 163,500 | 163,500 | 1,198,131 | 162,500 | 733% | 99% |

| Apulia | 3,482,500 | 3,031,200 | 5,572,059 | 1,150,000 | 184% | 38% |

| Basilicata | 256,000 | 256,000 | 938,569 | 233,500 | 367% | 91% |

| Calabria | 469,400 | 336,400 | 2,504,975 | 151,500 | 745% | 45% |

| Campania | 1,577,400 | 1,324,800 | 2,778,422 | 800,000 | 210% | 60% |

| ER | 4,329,600 | 4,170,100 | 12,435,655 | 3,853,500 | 298% | 92% |

| FVG | 777,000 | 888,000° | 4,867,339 | 725,000 | 548% | 82% |

| Latium | 1,948,200 | 1,832,400 | 4,951,762 | 1,684,000 | 270% | 92% |

| Liguria | 1,019,900 | 930,000 | 3,662,167 | 930,000 | 394% | 100% |

| Lombardy | 5,941,000 | 5,488,400 | 22,537,592 | 5,312,000 | 411% | 97% |

| Marche | 1,647,500 | 1,513,500 | 5,088,839 | 1,513,500 | 336% | 100% |

| Molise | 245,700 | 183,500 | 594,461 | 100,000 | 324% | 54% |

| Piedmont | 3,621,000 | 3,614,000 | 11,629,542 | 3,260,500 | 322% | 90% |

| Sardinia | 855,400 | 864,400° | 1,862,146 | 715,000 | 215% | 83% |

| Sicily | 2,042,800 | 1,523,900 | 7,413,006 | 1,353,000 | 486% | 89% |

| Tuscany | 3,437,800 | 3,177,500 | 12,347,763 | 2,846,000 | 389% | 90% |

| Umbria | 520,000 | 520,000 | 1,630,328 | 412,000 | 314% | 79% |

| Veneto | 3,349,900 | 3,265,000 | 14,694,412 | 3,166,000 | 450% | 97% |

| Other* | 38,400 | - | 17,348 | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Italy | 37,623,400 | 34,983,000 | 121,360,237 | 29,464,000 | 347% | 84% |

Legend I.U.: international unit; NHS: National Health Service; AP: Autonomous Province; ER: Emilia-Romagna; FVG: Friuli-Venezia Giulia;

the National Health Service demand can appear bigger than total demand on the basis of the fact that the former considers all movements related to the National Health Service expenditure recorded in medicinal products traceability that are tied to intermediate recipients (warehousemen, wholesalers, etc.), which are not envisaged in the total demand. The latter takes into account just the final users’ consumptions. In order to calculate self-sufficiency in the worst scenario, it was preferred to always consider the biggest value;

Other*: movements of medicinal products not univocally defined.

Conclusions

Over the last decade, a steady growth of both quality13 and safety25,26 of plasma for fractionation was recorded, despite the regional differences in terms of production, with a decreasing gradient from the Northern to the Southern Regions and Islands.

In Italy, the objective of self-sufficiency of albumin and IVIG has not yet been achieved. Indeed, their NHS demand is still only partially met by the toll fractionation supply. Although they constitute the driving products of the planning for PMP national manufacturing, the self-sufficiency level of albumin (especially) is significantly influenced also by the (probably low) appropriateness of its clinical usage. On the other hand, in 2011, the national self-sufficiency goal was achieved for pdFVIII, pdFIX (with all the aforementioned limitations) and PCCs. As far as pdFVIII is concerned, a surplus was recorded justifying all interventions aimed at providing a rational and ethical management of all products in excess22.

Though respecting the peculiarities of the treatment of both haemophilia and congenital bleeding disorders, in-depth evaluations of the usage of toll fractionation-derived pdFVIII and pdFIX products are worthwhile, in particular in relation to the coverage of pdFVIII total demand. As regards the PCCs, the regional framework is not uniform: some Regions (Abruzzo, Apulia, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Sardinia, and Umbria) significantly supply from the market, despite their productive capacity being 2 or 3 times higher than their own NHS demand24. It is worthwhile underlying that the latter demand does not include the usage of four-factors PCCs, which are not produced through contract manufacturing and, therefore, bought from the market, although there is still insufficient evidence to establish whether three- or four-factors PCCs differ in efficacy and safety in the reversal of antivitamin K anticoagulation27.

Currently, there is an ongoing debate involving all main stakeholders of the Italian national blood system on all potential definitions of the self-sufficiency concept, in qualitative and quantitative terms. There is a general consensus on the principle that the toll fractionation supply has to meet only the “appropriate” portion of the NHS demand for PMPs, whose determination and “threshold value” is particularly complex and debated in order to ensure and consequently achieve self-sufficiency.

In the absence of specific national recommendations on the self-sufficiency level to be achieved, in the present paper the threshold was arbitrarily set at 90% of NHS demand. This choice is not free of planning, organisational and economic consequences.

Far from providing a comprehensive discussion on the issue, it is worthwhile mentioning some of the consequences of the self-sufficiency threshold fixed at 100%. The latter, through a twelve-month potential availability of contract manufacturing PMPs, would make the Regions completely independent from international price fluctuations28. However, they would not be exempt from other unforeseen events also jeopardising the commercial market such as unavailability of raw material in consequence of regulatory measures29–31 or problems related to manufacturing or distribution32. In addition, should the Regions depend on a single manufacturing contract, the burden of these risks would be higher. Increasing the number of potential industrial partners and identifying a second services provider33 with new toll fractionation agreements could decrease, though not completely eliminate, the above-mentioned risk related to possible shortages.

Moreover, it is important to highlight the risk associated with the increase of toll fractionation share against the market portion. Potential suppliers of PMPs would be discouraged from staying in the market and there could be a reduction, or even a complete lack, of availability of products in case of shortage.

Therefore, in order to ensure continuity of supplies, even lower thresholds of self-sufficiency guaranteeing the product availability for at least nine months (e.g. current levels of IVIG production) could be defined with the aim of mitigating the aforementioned risks, internal and external to the National Blood System.

In addition, the definition of a self-sufficiency threshold requires a detailed cost-benefit analysis to assess system sustainability. In this regard, the ongoing project of the Italian National Blood Centre is strategic; in fact, it aims at defining standard mean costs of production and national tariffs for blood components and PMPs34, which can be compared to public pharmaceutical expenditure35, and provide useful indications for identifying the desirable and sustainable level of self-sufficiency.

Furthermore, the evolution of the Italian regulatory framework related in particular to the opening of the toll fractionation market will introduce new elements in the scenario of PMP manufacturing7. Regions could supposedly benefit from a stronger competition in terms of qualitative and quantitative offer of all toll fractionation products, with potential variations of industrial yields and PMP self-sufficiency levels. The opening of the market to new fractionators could also lead to a redefinition of interregional aggregations/consortia for plasma manufacturing with the purpose of constituting uniform groups with a perspective of better management and sustainability of PMP production.

Last but not least, a self-sufficiency plan must comply with the ethical aspects and founding principles of the national blood system36. The latter, according to national legislation, is based on voluntary, periodic, responsible, anonymous and non-remunerated donations and recognises the role of Associations and Federations of voluntary blood donors within the NHS. Moreover, human blood cannot be considered as a source of profit in accordance with the convention on human rights and biomedicine37, which prohibits financial gain from the use of any part of the human body38.

In conclusion, all the above-described aspects have to be duly considered in elaborating the annual national programme for self-sufficiency2–5 and the programme for the development of plasma collection in blood establishments and blood collection units as well as in promoting the rational and appropriate use of PMPs envisaged by law2–6. In addition, the analysis of regional usage of PMPs, by distribution channel, as well as the assessment of regional deviations from PMP national mean utilisation, together with international benchmarking14–16,22,24, are useful tools to identify not only clinicians who use PMPs inappropriately but also clinical settings where these medicinal products are still being exploited without robust evidence-based indications.

Footnotes

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO Expert Group. Expert Consensus Statement on achieving self-sufficiency in safe blood and blood products, based on voluntary non-remunerated blood donation (VNRBD) Vox Sang. 2012;103:337–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2012.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Official Journal of Italian Republic no. 251 October 27th, 2005. Legge 21 ottobre 2005, n. 219 recante la Nuova disciplina delle attività trasfusionali e della produzione nazionale degli emoderivati. [Accessed on 30/08/2013]. Available at: http://www.centronazionalesangue.it/content/legge-21-ottobre-2005-2-219.

- 3.Official Journal of Italian Republic no. 82 April 9th, 2011. Decreto del Ministero della Salute 20 gennaio 2011 “Programma di autosufficienza nazionale del sangue e dei suoi prodotti per l’anno 2010”. [Accessed on 30/08/2013]. Available at: http://www.centronazionalesangue.it/sites/default/files/dm_20.01.2011_programma_nazionale_autosufficienza_2010.pdf.

- 4.Official Journal of Italian Republic no. 271 November 21st, 2011. Decreto del Ministero della Salute 7 ottobre 2011 “Programma di autosufficienza nazionale del sangue e dei suoi prodotti, per l’anno 2011”. [Accessed on 30/08/2013]. Available at: http://www.centronazionalesangue.it/sites/default/files/d.m._7.10.11_programma_nazionale_autosufficienza_2011_gu_22.11.11.pdf.

- 5.Official Journal of Italian Republic no. 241 October 15 th, 2012Decreto del Ministro della Salute del 4 settembre 2012. Programma di autosufficienza nazionale del sangue e dei suoi prodotti per l’anno 2012 Available at: http://www.centronazionalesangue.it/sites/default/files/programmazione_autosuff_2012_0.pdfAccessed on 30/08/2013

- 6.Official Journal of Italian Republic no. 19 January 23rd, 2008. Decreto legislativo 20 dicembre 2007, n. 261, Revisione del decreto legislativo 19 agosto 2005, n. 191, recante attuazione della direttiva 2002/98/CE che stabilisce norme di qualità e di sicurezza per la raccolta, il controllo, la lavorazione, la conservazione e la distribuzione del sangue umano e dei suoi componenti. [Accessed on 30/08/2013]. Available at: http://www.centronazionalesangue.it/sites/default/files/DECLEG20DIC2007.pdf.

- 7.Calizzani G, Vaglio S, Profili S, et al. The evolution of the regulatory framework for the plasma and plasma-derived medicinal products system in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s6–12. doi: 10.2450/2013.003s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrugia A, Evers T, Falcou PF, et al. Plasma fractionation issues. Biologicals. 2009;37:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Federation of Haemophilia. Contract Fractionation. third edition. [Accessed on 27/08/2013]. Available at: http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1225.pdf.

- 10.World Health Organization. Information sheet, Plasma contract fractionation program. [Accessed on 27/08/2013]. Available at: http://www.who.int/bloodproducts/publications/en/Information%20Sheet%20PLASMA.pdf.

- 11.Grazzini G. Clinical appropriateness of blood component transfusion: regulatory requirements and standards set by the Scientific Society in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2008;6:186–90. doi: 10.2450/2008.0049-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanzoni M, Biffoli C, Candura, et al. Plasma-derived medicinal products in Italy: information sources and flows. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s13–7. doi: 10.2450/2013.004s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grazzini G, Rossi G, Rafanelli D, et al. Quality control of recovered plasma for fractionation: an extensive Italian study. Transfusion. 2008;48:1459–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaglio S, Calizzani G, Lanzoni M, et al. The demand for human albumin in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s26–32. doi: 10.2450/2013.006s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candura F, Lanzoni M, Calizzani G, et al. The demand for polyvalent immunoglobulins in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s45–54. doi: 10.2450/2013.009s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liumbruno GM, Franchini M, Lanzoni M, et al. Clinical use and the Italian demand for antithrombin. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s86–93. doi: 10.2450/2013.014s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mannucci PM. Plasma-derived versus recombinant factor VIII concentrates for the treatment of haemophilia A: plasma-derived is better. Blood Transfus. 2010;8:288–91. doi: 10.2450/2010.0072-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franchini M. Plasma-derived versus recombinant factor VIII concentrates for the treatment of haemophilia A: recombinant is better. Blood Transfus. 2010;8:292–6. doi: 10.2450/2010.0067-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calizzani G, Arcieri R. Clinical and organisational aspects of haemophilia care: the patients’ view. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:110–1. doi: 10.2450/2011.0043-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gringeri A. Factor VIII safety: plasma-derived versus recombinant products. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:366–70. doi: 10.2450/2011.0092-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iorio A, Puccetti P, Makris M. Clotting factor concentrate switching and inhibitor development in hemophilia A. Blood. 2012;120:720–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-378927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calizzani G, Profili S, Candura F, et al. The demand for factor VIII and for factor IX in Italy and the toll fractionation product surplus management. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s64–76. doi: 10.2450/2013.011s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnouf T. Modern plasma fractionation. Transfus Med Rev. 2007;21:101–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franchini M, Liumbruno GM, Vaglio S, et al. Clinical use and the Italian demand for prothrombin complex. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s94–100. doi: 10.2450/2013.015s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabor E. The epidemiology of virus transmission by plasma derivatives: clinical studies verifying the lack of transmission of hepatitis B and C viruses and HIV type 1. Transfusion. 1999;39:1160–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39111160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velati C, Romanò L, Fomiatti L, et al. SIMTI Research Group. Impact of nucleic acid testing for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus on the safety of blood supply in Italy: a 6-year survey. Transfusion. 2008;48:2205–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodgers GM. Prothrombin complex concentrates in emergency bleeding disorders. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:898–902. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrugia A. International movement of plasma and plasma contracting. Dev Biol. 2005;120:85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CHMP Position statement on Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and plasma-derived and urine-derived medicinal products. European Medicines Agency; London: Jun 23, 2011. [Accessed on 16/07/2013]. EMA/CHMP/BWP/303353/2010. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Position_statement/2011/06/WC500108071.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revised Preventive Measures to Reduce the Possible Risk of Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) and Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) by Blood and Blood Products. Food and Drug Administration; May, 2010. [Accessed on 27/08/2013]. Guidance for Industry. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM213415.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calizzani G, Vaglio S, Vetrugno V, et al. Management of notifications of donors with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (post-donation information) Blood Transfus. 2013 doi: 10.2450/2013.0035-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boulis A, Goold S, Ubel PA. Responding to the immunoglobulin shortage: a case study. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2002;27:977–99. doi: 10.1215/03616878-27-6-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CBS & Plasma Protein Products: All you ever wanted to know… Canadian Blood Services. [Accessed on 13/08/2013]. Available at: http://www.transfusionmedicine.ca/sites/transfusionmedicine/files/events/Fraction%20process%20CBS%20overview%20-%20resident%20seminar%202012.pdf.

- 34.Grazzini G, Ceccarelli A, Calteri D, et al. Sustainability of a public system for plasma collection, contract fractionation and plasma-derived medicinal product manufacturing. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s138–47. doi: 10.2450/2013.020s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lanzoni M, Candura F, Calizzani G, et al. Public expenditure for plasma-derived and recombinant medicinal products in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2013;11(Suppl 4):s110–7. doi: 10.2450/2013.017s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrini C. Production of plasma-derived medicinal products: ethical implications for blood donation and donors. Blood Transfus. 2013 doi: 10.2450/2013.0167-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. Council of Europe; Oviedo: Apr 04, 1997. [Accessed on 13/08/2013]. Available at: http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/164.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrini C. Is my blood mine? Some comments on the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:321–3. doi: 10.2450/2012.0103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]