Abstract

Importance

Survival varies widely in Stage III melanoma. The existence of clinical significance for positive NSLN status would warrant consideration for incorporation into the AJCC staging system and better prediction of survival.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether disease limited to the sentinel lymph node (SLN) represents different clinical significance than disease spread into nonsentinel lymph nodes (NSLN).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Our database was queried for all patients with positive SLN for cutaneous melanoma who subsequently underwent completion lymph node dissection.

Main Outcome Measures

Disease-free, melanoma-specific, and overall survival

Results

4,223 patients underwent SLN biopsy from 1986–2012. 329 patients had a tumor positive SLN. 250 (76%) had no additional positive nodes. 79 (24%) had a positive NSLN. Factors predictive of NSLN positivity included older age (p=0.04), thicker breslow (p<0.0001), and ulceration (p<0.015). Median overall survival (OS) was 178 months for the SLN+ only group and 42.2 months for the NSLN+ group (5-yr OS, 72.3% and 46.4% respectively.) Median disease-specific survival (DSS) was not reached for the SLN+ only group and was 60 months for the NSLN+ group (5-yr DSS 77.8% and 49.5% respectively.) On multivariate analysis, NSLN positivity had a strong association with recurrence, {HR: 1.754 (1.228–2.505); p=0.002}, shorter OS {HR: 2.24 (1.476–3.404); p=0.0002} and shorter DSS {HR: 2.225 (1.456–3.072); p<0.0001}. To further control for the effects of total positive nodes, comparison was done for those with N2 disease only (2–3 total positive LN), this confirmed the independent effect of NSLN status (DSS; p=0.04).

Conclusions

NSLN positivity is one of the most significant prognostic factors in patients with Stage III melanoma. An AJCC sub classification of nodal stage based on NSLN positivity should be considered.

Introduction

Regional lymph node metastasis in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma is the most important prognostic factor for tumor recurrence and survival. Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has become one of the most important clinical tools in the staging of melanoma since its introduction by Morton and colleagues [1]. Its ability to detect the 20% of patients with occult lymph node metastases has been validated in the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT I) [2–4]. The premise of the sentinel node is that melanoma follows an orderly progression of locoregional spread from the primary site to the draining lymph node basin.

Current guidelines state that all patients with a positive SN should undergo CLND as there is no other reliable means of detecting nonsentinel lymph node metastasis (NSLN), but CLND entails the risk of morbidity including seroma, infection, nerve injury and lymphedema. In addition of the patients who undergo CLND 80–90% have no additional positive nodes [5, 6]. Given this low positivity rate many have begun to question whether CLND is necessary [7]. Whether the nonsentinel nodes represent a different echelon of nodes has not been validated and the significance of the ability of disease to spread past the SN with a positive NSLN is not completely known. Several recent studies have suggested that a positive NSLN in the remainder of the lymph basin is a negative prognostic factor [8–12]. Thus, the value of CLND even if it may not necessarily improve survival, could provide additional prognostic staging information.

Five-year survival in patients with stage III disease ranges from 24–72% [4]. As therapies become more and more promising those with known worse prognostic factors may become more likely candidates for additional therapies. The official guidelines for staging melanoma were updated in 2009 by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Current AJCC staging for stage III melanoma takes into account primary tumor ulceration and mitoses, nodal tumor burden and the presence of in-transit metastases. It does not take into account whether the positive nodes are sentinel nodes or nonsentinel nodes.

Refining the AJCC staging system to provide a more accurate prognostic assessment could facilitate selection of patients for adjuvant therapy. Here we aim to determine firstly whether there are clinical factors which can predict NSLN positivity, whether NSLN positivity portends a worse survival than SN positivity alone, and whether this worse survival continues even after adjustment for other factors associated with decreased survival such as age, sex, breslow depth, ulceration, and number of positive nodes.

Patients and Methods

Patients were selected from a prospectively maintained database at the John Wayne Cancer Institute at Saint John’s Health Center (JWCI), and this study of deidentified data was approved for institutional review board exemption. A query was performed to identify 4,223 patients who underwent a SLN biopsy from the years of 1986 to 2012. Although selection criteria for sentinel node biopsy have varied over the course of the study period, in the earlier days of sentinel node staging the pathology protocol was less extensive and thus less sensitive, however, as time has gone by we have broadened our indications for sentinel node examination. These two factors may negate each other. Exclusion criteria included those with a primary other than cutaneous (i.e. mucosal or ocular) and those who did not undergo a CLND. Demographics and tumor information were collected including age, sex, primary tumor characteristics (anatomical site, Clark level, Breslow depth, and ulceration), sentinel node positivity, and nonsentinel node positivity.

SLN biopsy was offered to patients with primary melanoma ≥ 1 mm in thickness and to selected patients with thickness < 1 mm with other predictive features (ulceration, high mitotic rate, young age). Lymphatic mapping was performed with intradermal injection of 99m technetium filtered sulfur colloid and isosulfan blue at the primary site. Lymphoscintigraphy was used to identify the draining lymph node basin and the sentinel node(s) were marked. In the operating room 1 to 2 ccs of isosulfan blue was injected intradermally prior to skin incision. A hand held gamma probe and blue dye visualization were used to identify the SLN. All blue nodes, hot (10% of the hottest count), and palpably suspicious nodes were then sent to pathology.

All sentinel lymph nodes were placed in formalin for permanent sectioning. The nodes were paraffin embedded and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and with immunohistochemical stains for S-100 protein, HMB-45 and Melan-A. All those with positive SNs then were recommended for CLND. NSLN were evaluated by pathology by H&E staining of bivalved lymph nodes.

Statistical analysis was performed with the SAS software. Clinicopathological descriptive features were compared in the SLN+ only group and SLN+, NSLN+ group. Survival was determined by the Kaplan-Meier method and comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to determine the importance of NSLN positivity on survival relative to other variables. The Fisher exact test was used to test the correlation between patient characteristics and NSLN positivity. Primary outcome measures were disease free survival (DFS), defined as period from initial primary diagnosis until the first melanoma recurrence, melanoma-specific survival defined as the period from the initial primary diagnosis until occurrence of melanoma-specific death, and overall survival defined as the period from the initial primary diagnosis until occurrence of death from any reason. P-value <0.05 was considered significant

Results

We identified 3,989 patients who underwent sentinel node biopsy between 1986 and 2012. Of those patients there were 329 patients with positive SLN. 250 patients had positive SLN only and a negative CLND. 79 patients had positive NSLN in addition to their positive SLN. Of those with only SLN positive, 190 (76%) had one positive node (N1), 52 (20.8%) had two positive nodes (N2), six (2.4%) had three positive nodes (N2) and two (0.8%) had four or more positive nodes (N3). Of those with positive NSLN in addition to their positive SLN 27 (34.2%) had a total of 2 positive nodes (N2), 21 (26.6%) had 3 positive nodes (N2), and 31 (39.2%) had four or more positive nodes (N3).

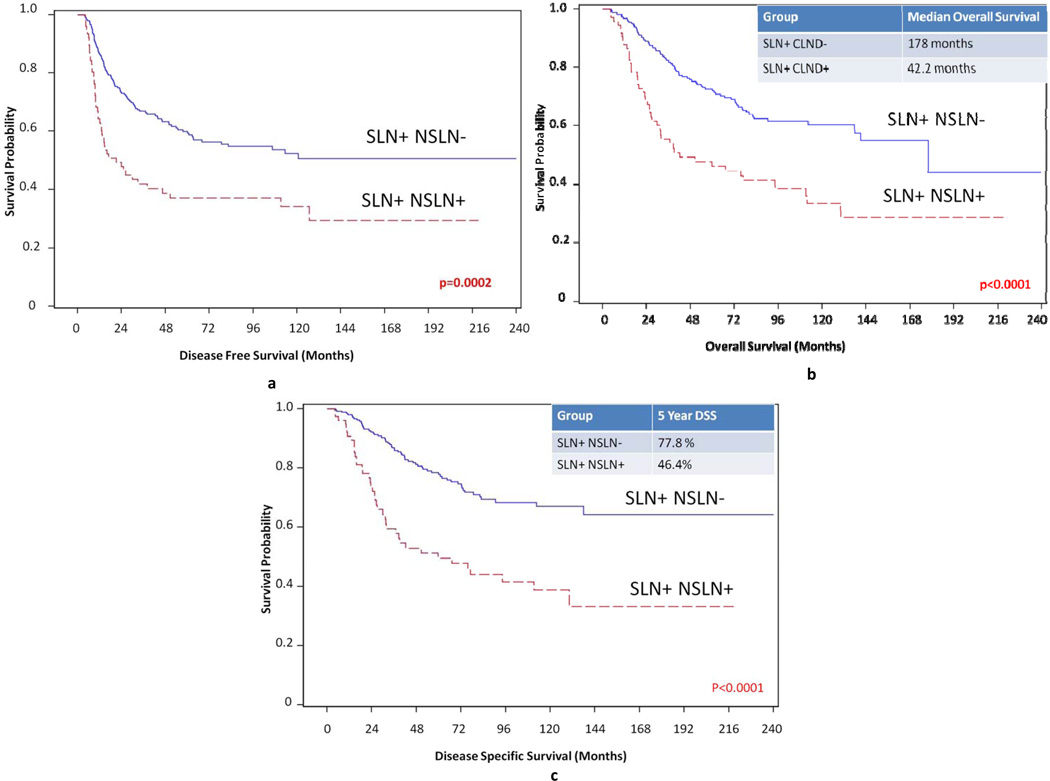

There was no difference in the gender distribution, primary tumor location, or histology between the SLN only + group and the SLN+, NSLN+ group. The average age of the SLN+ only group was 51 which was significantly younger than the average age of 56 of the NSLN+ group (p=0.04). The NSLN+ group tended to have deeper T3 or T4 lesions and higher Clark levels versus the SLN+ only group (p<0.0001). The NSLN+ group also tended to have ulceration of their lesions (p<0.0153). Demographics and tumor specific variables of both SLN+ only group, and SLN+, NSLN+ patients are shown in Table 1. The 5 year disease free survival (DFS) was significantly longer for the SLN+ only group than for the SLN+, NSLN+ group p=0.0002 (Figure 1a). Median overall survival was 178 months for the SLN+ only group and 42.2 months for the NSLN+ group. The 5 year overall survival (OS) was 72.3% for the SLN+ only group and 46.4% for the SLN+, NSLN+ group p<0.0001 (Figure 1b). Median disease specific survival (DSS) was not reached for the SLN+ only group and was 60 months for the NSLN+ group. The five year melanoma specific survival was 77.8% for the SLN+ only group and 49.5% for the SLN+, NSLN+ group p<0.0001 (Figure 1c).

Table 1.

Demographics, Clinical and Tumor specific variables for SLN+NSLN−patients versus SLN+NSLN+ patients. Statistical analysis performed by Chi-square and ANOVA.

| SLN+, NSLN− n (%) | SLN+, NSLN+, n(%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | p=0.287 | ||

| Male | 156 (62.4%) | 44 (55.7%) | |

| Female | 94 (37.6%) | 35 (44.3%) | |

| Age at diagnosis (mean) | 51 | 56 | p=0.04 |

| Location of Primary tumor | p=0.67 | ||

| Head and neck | 41 (16.4%) | 12 (15.2%) | |

| Trunk | 101 (40.4%) | 27 (34.2%) | |

| Lower Extremity | 78 (31.2%) | 30 (38%) | |

| Upper Extremity | 30 (12%) | 10 (12.6%) | |

| Histology | p=0.29 | ||

| Superficial Spreading | 92 (36.8%) | 18 (22.8%) | |

| Nodular | 68 (27.2%) | 30 (38.0%) | |

| Acral Lentinginous | 15 (6%) | 7 (8.9%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 75 (30%) | 24 (30.3%) | |

| Breslow Thickness | p<0.0001 | ||

| T1: 0.01–1.00 | 38 (15.2%) | 4 (5.1%) | |

| T2: 1.01–2.00 | 92 (36.8%) | 14 (17.7%) | |

| T3: 2.01–4.00 | 77 (30.8%) | 36 (45.6%) | |

| T4: >4 | 32 (12.8%) | 23 (29.1%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (4.4%) | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Ulceration | p=0.0153 | ||

| Yes | 54 (21.6%) | 28 (35.4%) | |

| No | 174 (69.6%) | 49 (62.0%) | |

| Unknown | 22 (8.8%) | 2 (2.6%) | |

| Clark level | p=0.0104 | ||

| I | 23 (9.2%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| II | 8 (3.2%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| III | 43 (17.2%) | 7 (8.9%) | |

| IV | 157 (62.8%) | 50 (63.3 %) | |

| V | 19 (7.6%) | 16 (20.2%) |

Figure 1.

a: 5 year disease specific survival for SLN+ only patients versus SLN+, NSLN+ patients. 5 year disease specific survival was significantly shorter for the SLN+ only group versus the SLN+, NSLN+ group (p=0.0002)

b: Overall survival for SLN+ only patients versus SLN+, NSLN+ patients. Median overall survival was 178 months for SLN+ only patients versus 42.2 months for SLN+, NSLN+ patients. Five year overall survival was 72.3% for SLN+ only patients versus 46.4% for SLN+, NSLN+ patients (p<0.0001)

c: Disease specific survival for SLN+ only patients versus SLN+, NSLN+ patients. Five year disease specific survival was 77.8% for the SLN+ only group and 49.5% for the SLN+, NSLN+ group (p<0.0001)

To determine whether this worse prognosis in the SLN+, NSLN+ group was attributable to the spread of disease beyond the SLN or simply due to an increase in the number of involved nodes, analysis was done with adjustment for the higher number of lymph nodes in the SLN+, NSLN+ group. The SLN+, NSLN+ group had a HR of 1.91 (1.351–2.727, p=0.0003) for disease free survival, 2.115 (1.456–3.072, p<0.0001) for overall survival and 2.115 (1.456–3.072) for melanoma specific survival.

To determine whether spread of disease beyond the SLN was truly an independent prognostic indicator of decreased survival we performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis on patient tumor SLN and NSLN factors. For DFS, multivariate analysis found older age (HR 1.026 (1.015–1.036), p<0.0001)), male sex (HR 1.443 (1.024–2.034), p=0.0362), increasing number of SLN positive (HR 1.451 (1.190–1.770), p=0.0002), and NSLN positivity (HR 1.754 (1.228–2.505), p=0.002) to be predictive of higher rate of recurrence. NSLN positivity increased the risk of recurrence with a 1.7 fold greater likelihood of recurrence than the SLN only positive group. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis for Disease-Free, Overall and Disease-Specific Survival SLN+, NSLN− patients versus SLN+, NSLN+ patients.

| Parameter | Comparison | P -value | Hazard Ratio |

95% CI Lower Limit |

95% CI Upper Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Free Survival | |||||

| Total # nodes | (as # increases) | 0.0002 | 1.451 | 1.190 | 1.770 |

| NSLN positivity | (positive v. negative) | 0.0020 | 1.754 | 1.228 | 2.505 |

| Age | Increasing in age | <0.0001 | 1.026 | 1.015 | 1.036 |

| Male | Male v. female | 0.0362 | 1.443 | 1.024 | 2.034 |

| Ulceration | Yes | 0.161 | 1.311 | 0.896 | 1.919 |

| Overall Survival | |||||

| Total # SLN + | (as # increases) | <0.0001 | 1.637 | 1.301 | 2.059 |

| NSLN positivity | (positive v. negative) | 0.0024 | 1.822 | 1.236 | 2.685 |

| Age | Increasing in age | <0.0001 | 1.032 | 1.020 | 1.044 |

| Male | Male v. female | 0.0332 | 1.528 | 1.034 | 2.257 |

| Breslow | (as increases) | 0.0396 | 1.032 | 1.002 | 1.064 |

| Ulceration | Yes | 0.2842 | 1.283 | 0.840 | 1.959 |

| Disease Specific Survival | |||||

| Total # SLN + | (as # increases) | 0.0033 | 1.487 | 1.141 | 1.936 |

| NSLN positivity | (positive v. negative) | 0.0002 | 2.242 | 1.476 | 3.404 |

| Age | Increasing in age | 0.0002 | 1.024 | 1.011 | 1.037 |

| Breslow | (as increases) | 0.0070 | 1.044 | 1.012 | 1.076 |

| Ulceration | yes | 0.3958 | 1.225 | 0.767 | 1.957 |

For OS, multivariate analysis found older age (HR 1.032 (1.020–1.044, p<0.0001)), male sex (HR 1.528 (1.034–2.257), p=0.0332)), higher breslow (HR 1.032 (1.002–1.064), p=0.0396), increasing number of SLN positive (HR 1.637 (1.301–2.059), p<0.0001), and NSLN positivity (HR 1.822 (1.236–2.685), p=0.00024) to be predictive of shorter overall survival. NSLN positivity decreased overall survival with a 1.8 fold risk of death than SLN positivity alone. (Table 2)

For melanoma specific survival, multivariate analysis found older age (HR 1.024 (1.011–1.037), p=0.0002), deeper breslow (HR 1.044 (1.012–1.076), p=0.007), increasing number of SLN positive (HR 1.487 (1.141–1.936), p=0.0033), and NSLN positivity (HR 2.242 (1.476–3.404), p=0.0002) to be predictive of shorter melanoma specific survival. NSLN positivity decreased melanoma specific survival with a 2.2 fold greater likelihood of death secondary to melanoma (Table 2).

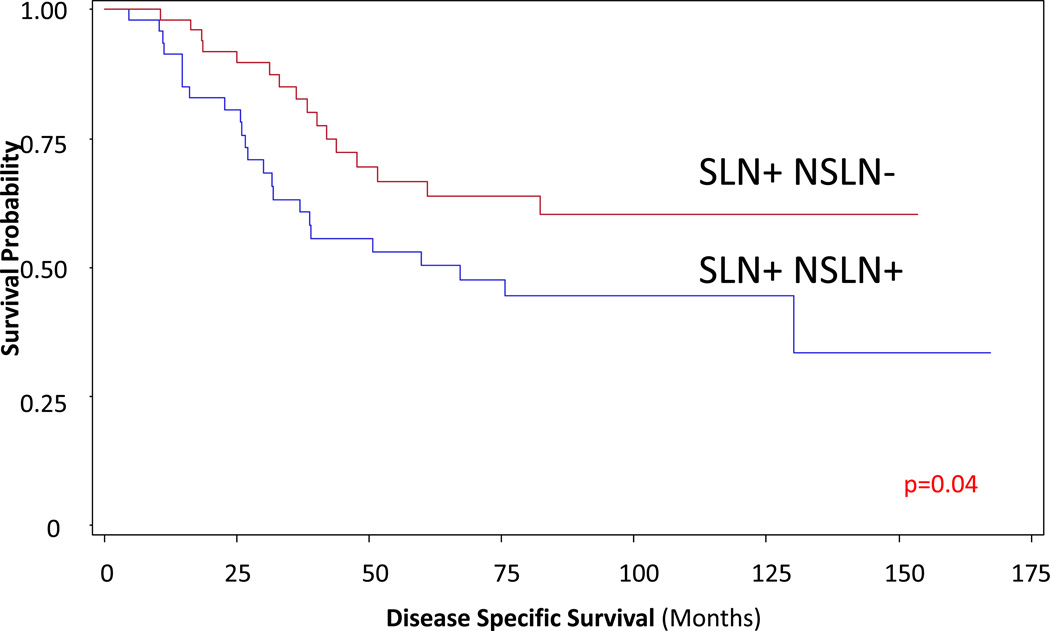

To further control for the total number of positive nodes, comparison was done for patients who had N2 disease only (2–3 positive LN). This confirmed the independent effect of NSLN status on disease specific survival when controlled for number of positive nodes (DSS p=0.04) (Figure 5)

Discussion

Our data support a prognostic difference between a positive SLN and a positive NSLN. There is no dispute that currently SLN biopsy is the most reliable method for nodal staging. Its advent has revolutionalized surgery for metastatic melanoma. The prognostic value of a positive SLN has been validated by the first MSLT trial [2]. The prognostic information that can be obtained from a positive NSLN is less evident. Currently there have been several studies which have examined the significance of a positive non-sentinel node.

Cascinelli et al performed a retrospective analysis on their patients with 176 total patients 143 with SLN+ only and 33 with SLN+, NSLN+. Results from their analysis showed a 5 year survival of 92.6% for the SLN only group and 60% for the SLN+, NSLN+ group. Their conclusion was that NSLN allows identification of patients with nodal disease that are at a different risk level for death. Flaws to this study include that the group did not adjust for the higher number of positive nodes in the NSLN+ group [9].

Roka et al examined their 85 SLN+ patients, 67 patients had SLN+ only and 18 had SLN+, NSLN+. On univariate analysis recurrence rates were significantly lower in the SLN+ NSLN− group vs. SLN+ NSLN+ only group (87% versus 78% p=0.02) and death from disease was also significantly lower in the SLN+ NSLN− group v. SLN+ NSLN+ group. Of note this study’s main purpose was to assess factors most strongly associated with positive NSLN status. No multivariate analysis was done and this group also did not account for the worse prognosis associated with the higher number of nodes in the SLN+, NSLN+ group [8].

Brown et al identified 296 patients who were SLN+, NSLN− and 51 SLN+, NSLN+ patients. The 5 year DFS was 64.8% and 42.6% respectively with p<0.001 and 64.9% and 49.4% for overall survival with p<0.001. Their analysis held true even after the total number of positive LN and NSN status were evaluated using multivariate analysis (p<0.01) [12]

Ghaferi had a group of 90 SLN+NSLN− which were compared to 41 SLN+NSLN+. Their study showed that an involved NSLN was a statistically significant predictor of outcome on multivariate analysis. The hazard ratio for a positive NSLN was 1.92 (1.27–2.89) for overall survival and 1.79 (1.01–3.19) for distant disease free survival. Their analysis was limited to patients with 2–3 positive nodes to adjust for the worse survival that would be seen with a greater number of positive nodes [10].

Ariyan et al. examined their 222 patients who underwent SLN biopsy in their restrospectively maintained database. 185 of these patients were SLN+, NSLN− and 37 patients were SLN+, NSLN+. Median survival between these two groups was 104 months versus 36 months (p<0.001). On adjustment for the number of positive nodes by analyzing patients with an equal number of nodes the presence of a positive NSLN was still associated with worse melanoma specific survival (66 months versus 34 months p<0.04). On multivariate analysis positive NSLN was an independent predictor of disease specific survival with HR of 2.5 [11].

Our data corroborates the findings of these previous studies which show that positive NSLN appear to be prognostically different than positive SLN. Currently all patients with a positive SLN are recommended to undergo a CLND. However, only 20% of patients with a positive SLN go on to have additional nodes with tumor in the remainder of their nodal basin. MSLT II was designed to determine whether nodal observation is an acceptable alternative to completion nodal dissection for patients with positive sentinel nodes. Until completion of this trial, benefits of the result of completion nodal dissection should be strongly considered

It is abundantly clear that the quantity of lymph node involvement with metastatic melanoma carries prognostic significance. The number of involved nodes determines nodal stage in the current AJCC system and is directly related to risk of melanoma death. This significance has been validated in numerous datasets. In addition, the tumor burden of the SLN is associated with both NSLN involvement and overall prognosis.

Our study suggests that there is also a qualitative difference between the prognostic significance of sentinel and non-sentinel lymph nodes. That is, adjusting for the number of involved nodes, the distinction between metastasis only to lymph nodes receiving direct drainage from the primary site (i.e. sentinel nodes) and other, higher-echelon nodes remains significant. The source of this difference is unknown, but one can speculate that it is either related to an increased potential for dissemination of the tumor cells or a decreased ability in some SLN to contain or respond to tumor cells.

Data from this study demonstrate that NSLN involvement is more common with aggressive tumor characteristics (e.g. thickness and ulceration) and with host characteristics (e.g. age.). Prior studies have made it clear that the risk of NSLN metastasis can be quantified, not only based upon primary tumor characteristics, but also SLN tumor location and burden. Our group has previously shown that NSLN involvement increases significantly if >5% of the SLN area is replaced by tumor, though this quantification was not available for the patients in this analysis. The same biologic abilities that allow tumor cells to penetrate initial immune stations may also allow hematogenous dissemination. We have previously demonstrated a decline in lymphatic function in elderly patients with decreased retention or concentration of radiotracers used in SLN mapping. This inability to retain colloid particles may parallel an inability to retain tumor cells, leading to higher NSLN, and perhaps distant site involvement. These tumor biology and immunologic questions could be investigated, and may provide useful information regarding the process of melanoma metastasis.

In the current study, we did not have access to information regarding potentially important variables including the tumor burden within the SLN and the presence of microscopic metastases in NSLN that were not evident by H&E staining. While these data might affect the results of our multivariable analysis, they may not be practical to include into the staging system currently. Exhaustive sectioning and immunohistochemical staining of NSLN is likely to be impractical for the pathologist, and no consensus exists regarding the most appropriate measurement system to quantify SLN tumor burden. At present, NSLN involvement, as identified by current standard pathologic processing carries powerful, independent prognostic information and is simple to obtain.

The AJCC guidelines were updated in 2009 and were made based on the analysis of 17,600 patients in the AJCC Melanoma Staging Database with 3,307 Stage III patients. Statistical analyses of survival data determined the factors important for staging and prognosis. We propose that for the next iteration of the staging system, the Committee perform an analysis of the independent prognostic impact of NSLN status. Should that analysis confirm the findings of our series and others, this simple, readily available datapoint should be included in the next staging system.

Figure 2. Comparison of patients with only 2–3 total nodes positive (SLN+ only versus SLN+, NSLN+ patients).

This confirms the independent effect of NSLN status on disease specific survival (p=0.04)

Acknowledgments

Supported by Award Number P01 CA29605 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Supported in part by fellowship funding from the Harold McAlister Charitable Foundation (Los Angeles, CA) (Dr. Leung).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 85th Annual Conference of the Pacific Coast Surgical Association, Kauai, HI, February 16–19, 2013

References

- 1.Morton DL, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992;127(4):392–399. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420040034005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton DL, et al. Validation of the accuracy of intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for early-stage melanoma: a multicenter trial. Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial Group. Ann Surg. 1999;230(4):453–463. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00001. discussion 463-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton DL, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for early-stage melanoma: accuracy and morbidity in MSLT-I, an international multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):302–311. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000181092.50141.fa. discussion 311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton DL, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1307–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMasters KM, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: controversy despite widespread agreement. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2851–2855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elias N, et al. Is completion lymphadenectomy after a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy for cutaneous melanoma always necessary? Arch Surg. 2004;139(4):400–404. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.4.400. discussion 404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, et al. Factors predictive of tumor-positive nonsentinel lymph nodes after tumor-positive sentinel lymph node dissection for melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3677–3684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roka F, et al. Prediction of non-sentinel node status and outcome in sentinel node-positive melanoma patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(1):82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cascinelli N, et al. Sentinel and nonsentinel node status in stage IB and II melanoma patients: two-step prognostic indicators of survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4464–4471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghaferi AA, et al. Prognostic significance of a positive nonsentinel lymph node in cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(11):2978–2984. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0665-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariyan C, et al. Positive nonsentinel node status predicts mortality in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(1):186–190. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0187-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown RE, et al. The prognostic significance of nonsentinel lymph node metastasis in melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 17(12):3330–3335. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torisu-Itakura H, et al. Molecular characterization of inflammatory genes in sentinel and nonsentinel nodes in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(11):3125–3132. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]