Abstract

MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] was obtained from liquid culture of Pestalotiopsis photiniae isolated from the Chinese Podocarpaceae plant Podocarpus macrophyllus. MP significantly inhibited the proliferation of HeLa tumor cell lines. After treatment with MP, characteristic apoptotic features such as DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation were observed in DAPI-stained HeLa cells. Flow cytometry showed that MP induced G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. Western blotting and real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction were used to investigate protein and mRNA expression. MP caused significant cell cycle arrest by upregulating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27KIP1 protein and p21CIP1 mRNA levels in HeLa cells. The expression of p73 protein was increased after treatment with various MP concentrations. mRNA expression of the cell cycle-related genes, p21CIP1, p16INK4a and Gadd45α, was significantly upregulated and mRNA levels demonstrated significantly increased translation of p73, JunB, FKHR, and Bim. The results indicate that MP may be a potential treatment for cervical cancer.

Keywords: MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide]; p73; Apoptosis

Introduction

Natural products and their derivatives have been a valuable chemical resource for finding promising drugs for the prevention and treatment of cancer (1). Recently, natural products isolated from endophytic fungi have attracted great attention. Some of these endophytes may produce bioactive substances involved in host-endophyte relationships. Many valuable bioactive compounds with anticancer activity have been successfully developed following discovery in endophytic fungi, such as taxol, camptothecin, and phenylpropanoids. Endophytes are also used as biocatalysts in the biotransformation process of natural products to obtain novel bioactive compounds (2). A growing body of evidence indicates that the endophytic genus Pestalotiopsis represents a huge and largely untapped resource of natural products with chemical structures that have been optimized by evolution for biological and ecological relevance. So far, 196 secondary metabolites have been discovered in this genus.

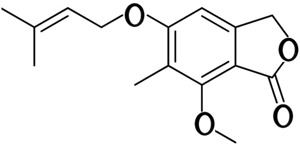

In our study, MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] was obtained from liquid culture of endophytic Pestalotiopsis photiniae isolated from the Chinese plant Podocarpus macrophyllus Figure 1, a member of the family Podocarpaceae. MP is a derivative of phthalides, and several derivatives of phthalides have been reported to possess a wide spectrum of pharmacological and biological activities including antiallergic, antibacterial, anticoagulant, antifungal, anticancer, and histamine-inhibitory activity (3, 4).

Figure 1. Structure of MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide].

MP was first isolated from Alternaria porri and reported to have antifungal activity and cytotoxic activity in cancer cell lines 9 (5- 7). Although cytotoxic activity of MP was reported, little was known about the molecular mechanism of this effect of MP. In the present study, we found that MP could induce G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells. MP upregulated mRNA expression of the p73, JunB, FKHR, Bim, p16INK4a, p21CIP1, and Gadd45α genes. The p73 and FKHR pathways may be involved in MP-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

Material and Methods

Material

MP was provided by our research group at Hebei University (purity >99%, HPLC analysis) (7) and dissolved in DMSO.

Cell culture

HeLa cell lines were purchased from the cell culture center of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences (IBMS), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS), China. HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

MTT assay

Cells were incubated in triplicate on 96-well plates with various concentrations of MP for the indicated times. The DMSO concentration was kept below 0.05%, where it was found to have no antiproliferative effect on the HeLa cells. MTT (20 μL, 5 mg/mL) was added to each well. After incubation at 37°C for 4 h, 100 µL 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-HCl was added, followed by incubation at 37°C overnight. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm. The 50% growth inhibitory concentration of MP on the cells was calculated from MTT data.

Flow cytometry assay

HeLa cells were treated with MP at concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL for 24 h. The control was treated with 0.05% DMSO. A total of 106 cells were collected by centrifuging at 100 g for 5 min; sedimented cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS. For cell cycle analysis, cells were fixed in ice-cold ethanol (70%, v/v) and stained with 0.5 mL propidium iodide (PI)/RNase staining buffer (BD Pharmingen, USA) for 15 min at room temperature and analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, USA). Apoptotic/necrotic cells were detected using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen). Briefly, cells were incubated with binding buffer (10 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2) and stained with PI and FITC-labeled Annexin V for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Cell fluorescence was evaluated by flow cytometry using a FacsCalibur (BD Biosciences, USA) instrument and analyzed by the Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences).

Nuclear DAPI staining

Exponentially growing cells were seeded on polylysine-coated glass coverslips on 24-well plates and cultured at 37°C, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. After incubation with MP, cells were washed with PBS three times, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X100 (v/v) in 0.1% sodium citrate (w/v) in PBS for 20 min. The control was treated with 0.05% DMSO. Cells were washed with PBS three times and then incubated with DAPI (1 µg/mL) at room temperature for 5 min in the dark. After DAPI staining and a short washing step, coverslips were mounted and the fluorescence was visualized under fluorescent microscopy (Olympus, Japan).

Western blot analysis

After treating cells with 0, 30, 40, and 50 μg/mL MP for 24 h, they were harvested. The control was treated with 0.05% DMSO. Subsequently, cells were incubated in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-NaOH, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.7 μl/mL pepstatin, 0.5 μL/mL leupetin, 2 μg/mL aprotinin) for 10 min on ice. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 15 min at 15,000 g. Protein concentrations in lysates were determined by the Bradford assay. Fifty micrograms of protein lysate per sample was denatured in 2X sample buffer and loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide 8-12% Tris-glycine gels. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA) followed by blocking with 5% non-fat milk (w/v) in Tris-buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with specific primary antibodies for 1 h. After they were washed, the membranes were incubated with appropriate secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies and visualized by electrochemoluminescence. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies for p73 (S-20) and p27KIP1 (C-19) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA).

Real-time RT-PCR

Approximately 106 cells were harvested at the indicated time and total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. The integration of RNA was detected by agarose gel analysis and A260 spectrophotometry. Reverse transcription of total RNA was performed by PrimeScript™ High Fidelity RT-PCR Kit (Takara, Japan). Real-time RT-PCR was performed using an iCycler PCR machine (Bio-Rad, USA). Specificity of each PCR was examined by the melting temperature profiles of the final products. Standard curves were calculated using cDNA to determine the linear range and efficiency of each primer pair. Reactions were done in triplicate, and the relative amounts of gene were normalized to GAPDH. Relative gene expression data were analyzed by the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT method) as follows: p16INK4a (8), sense: GGGGGCACCAGAGGCAGT, antisense: GGTTGTGGCGGGGGCAGTT; Bim (9), sense: ATCCCCGCTTTTCATCTTTA, antisense: AGGACTTGGGGTTTGTGTTG; FKHR, sense: TCGTCATAATCTGTCCCTACACA, antisense: GGCTCTTAGCAAA; p73 (10), sense: CATGGAGACGAGGACACGTACTAC, antisense: CTCCATCAGCTCCAGGCTCT; GADPH (11), sense: TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC, antisense: GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG; JunB (12), sense: CTGGTGGCCTCTCTCTACACG, antisense: CCCGCGGGGGTAAAAGTACTG; p21CIP1 (10), sense: CCTCATCCCGTGTTCTCCTTT, antisense: GTACCACCCAGCGGACAAGT; Gadd45α (10), sense: TCAGCGCACGATCACTGTC, antisense: CCAGCAGGCACAACACCAC; p27KIP1 (13), sense: AGCCAGCGCAAGTGGAATTT, antisense: TTGGGGAACCGTCTGAAACA; CCNE1 (14), sense: GAAATGGCCAAAATCGACAG, antisense: CCGGTCATCATCTTCTTTG.

Statistical analysis

All data are reported as means±SD. Microsoft Office Excel was used for data analyses. Differences between the treatment groups were assessed using the two-tailed unpaired Student t-test. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity of MP on HeLa cell lines

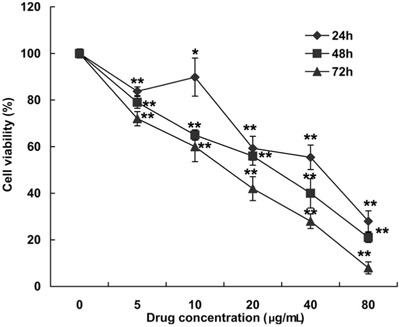

MP had an antiproliferative effect on HeLa cells. HeLa cells were treated with various concentrations of MP, and relative cell viability was assessed by MTT assay after 24, 48, and 72 h of culture Figure 2. The 50% growth inhibition concentration was 36, 22, and 13 μg/mL for 24-, 48-, and 72-h incubation, respectively.

Figure 2. Effect of MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] on the viability of HeLa cell lines. Cell viability was measured with the MTT assay. Cells were treated with 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μg/mL MP or with DMSO (0.05%) as the vehicle control for 24, 48 and 72 h. Results are reported as means±SD of triplicate independent experiments at each time point. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 compared with the control group (two-tailed unpaired t-test).

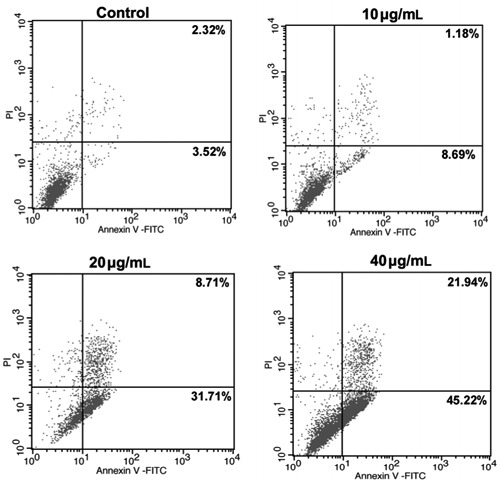

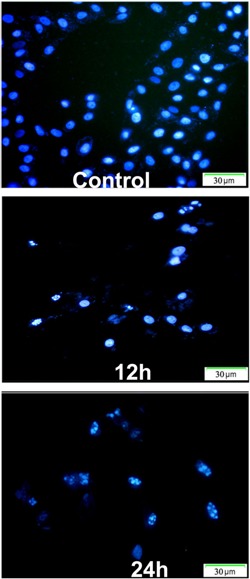

Apoptotic cell death was analyzed in HeLa cells treated with MP for various periods of time by flow cytometry using Annexin V-PI staining. The early apoptotic cells (regarded as Annexin V-positive and PI-negative) significantly increased from 2.32% in control cells to 8.69% (10 μg/mL), 31.71% (20 μg/mL), and 45.22% (40 μg/mL) Figure 3. In addition, cell death was assayed morphologically by fluorescence microscopy of DAPI staining. Compared with untreated cells, typical markers of apoptosis such as significant chromatin condensation, nuclear deformation, and disassembly were observed in drug-treated cells Figure 4. Overall, these results indicated that MP brought about cell death mainly by induction of apoptosis.

Figure 3. MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] induces apoptosis in HeLa cancer cells. HeLa cells were treated with 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL MP for 24 h, and then analyzed for apoptosis by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI). Controls were treated with 0.05% DMSO. Each value is the average of three independent experiments.

Figure 4. Nuclear morphological change after MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] treatment. DAPI staining of HeLa cells treated without or with 40 μg/mL MP for 12 and 24 h shows chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation. The control was treated with 0.05% DMSO for 24 h.

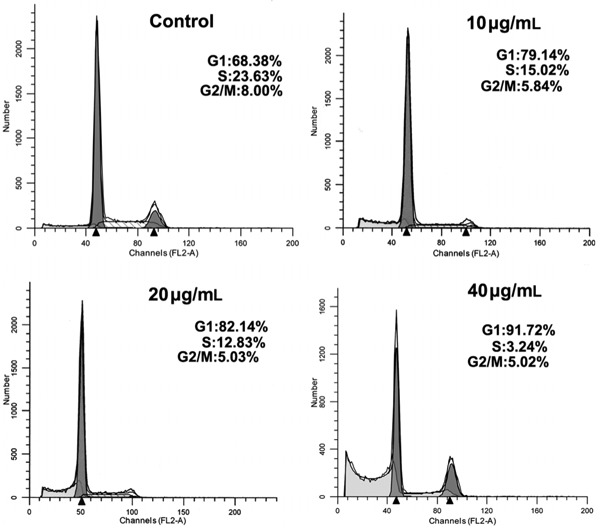

MP-induced G1 arrest of the cell cycle in HeLa cells

HeLa cells treated with various concentrations of MP accumulated in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, with a reduction in the percentage of cells in S phase Figure 5. These results suggested that MP inhibited cellular proliferation of HeLa cells via the G1 phase arrest of the cell cycle.

Figure 5. MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] caused cell cycle arrest in G1 phase. HeLa cells were treated with DMSO (0.05%) or 10, 20 and 40 μg/mL MP for 24 h, stained with propidium iodide, and their DNA content analyzed using flow cytometry. Each value represents the average of three independent experiments.

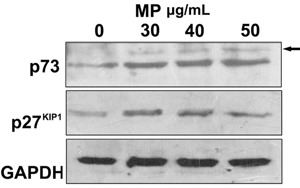

p27 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CKI) that can induce cell cycle arrest in G1 phase, thereby inhibiting cell proliferation (15). The amount of p27KIP1 protein was significantly increased Figure 6, but p27KIP1 mRNA expression was not changed Figure 7A.

Figure 6. Western blot analysis of p73 and p27KIP1 expression by HeLa cells exposed to various concentrations of MP (0, 30, 40, and 50 μg/mL). Control cells were treated with 0.05% DMSO. Cells were harvested and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Western blot analysis was performed using specific p27KIP1, p73 and GAPDH antibodies. Arrow indicates the nonspecific bands.

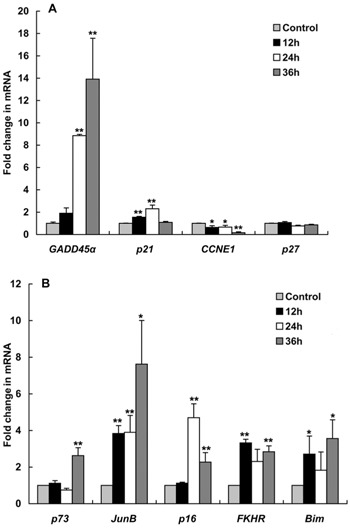

Figure 7. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of A, cell cycle-regulating gene expression and B, p73, JunB, p16INK4a, FKHR, and Bim gene expression. HeLa cells were treated with 40 μg/mL MP [4-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-5-methyl-6-methoxyphthalide] for 0, 12, 24, and 36 h. Control cells were treated with 0.05% DMSO. Data are reported as means±SD of triplicate independent experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 compared with the control group (two-tailed unpaired t-test).

The cell cycle-regulating genes, p21CIP1 and Gadd45α, were examined using real-time RT-PCR. p21CIP1 is another CKI that causes G1 arrest, and p21CIP1 mRNA expression was significantly increased at 12 and 24 h (1.5- and 2.3-fold) after drug treatment Figure 7A. Gadd45α can interact with p21CIP1 to promote G1 arrest (16). Gadd45α mRNA was significantly increased 8.8-fold at 24 h and 13.9-fold at 36 h (Figure 7A). The mRNA levels of cyclin E were also significantly reduced by 16% at 36 h (Figure 7A).

Effect of MP on mRNA expression of p73, p16INK4a and JunB

MP significantly increased p73 protein expression Figure 6. The expression of p73 mRNA was significantly higher (by 2.6-fold) at 36 h compared to the control. JunB is a p73-regulated gene that can induce p16INK4a expression (17). Subsequently, we examined the expression of JunB and p16INK4a mRNA. JunB expression was significantly increased at 12 h and achieved the maximum increase (7.6-fold) at 36 h. The expression of p16INK4a mRNA was significantly increased at 24 and 36 h (4.6- and 2.4-fold), respectively; Figure 7B.

Effect of MP on mRNA expression of FKHR and Bim genes

FKHR (FOXO1) is a forkhead box transcription factor, and it is often upregulated after drug treatment (18,19). FKHR induces apoptosis by upregulating several cell death genes such as Bim (20). The real-time RT-PCR results showed that MP significantly induced the expression of FKHR mRNA by 3.3-fold at 12 h. After treatment with MP, the mRNA levels of BH3-only genes, Bim, were significantly increased by 3.5-fold. FKHR and Bim mRNA increased in a similar manner Figure 7B.

Discussion

Phthalide derivatives are reported to have a variety of pharmacological activities, but there have been few reports on their anticancer activity. n-Butylidenephthalide and z-ligustilide, two phthalides isolated from Angelica sinensis, have recently been found to be cytotoxic against several brain tumor cell lines and leukemia cells (21). Two new phthalides, named zinnimide and deprenylzinnimide, isolated from A. porri were highly cytotoxic toward HeLa and KB cells (5). Little was known about the molecular mechanism of cytotoxic effects of phthalide derivatives. MP is a derivative of phthalides isolated from the endophytic fungi P. photiniae. Flow cytometry showed that MP induced G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. MP was able to induce marked apoptotic morphology in HeLa cells in a time-dependent manner.

We found that MP caused significant cell-cycle arrest in G1 phase. Cell cycle progression is controlled by a family of serine/threonine kinase holoenzyme complexes, composed of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). The activated CDK-cyclin complexes can phosphorylate their substrates on serines and threonines and are negatively regulated by CKIs. There are two known groups of CKIs. One group is the INK4 family (p16INK4a, p15INK4b, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d). The second group is the CIP/KIP family (p21CIP1 and p27KIP1) (22).

The amounts of p27KIP1 and p73 proteins were significantly increased Figure 6. Protein p73 is a member of the p53 family. Like p53, p73 induces G1 cell growth arrest. Due to its high homology to p53, the p53-related protein p73 is capable of trans-activating p53 target genes (23). Upregulation of p27KIP1 and p73 proteins may be involved in G1 cell cycle arrest after MP treatment, but further experimental evidence is needed for confirmation. p73 mRNA expression was only increased significantly after 36 h, but p73 protein levels were increased at 24 h. This inconsistency may be related to inhibition of p73 protein degradation, resulting in the observed increase in protein levels.

Cyclin E binds to G1 phase Cdk2, which is required for the transition from G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle and required for cell division. MP could significantly decrease the cyclin E mRNA levels. Higher expressions of p21CIP1 and Gadd45α genes may promote MP-induced G1 cell cycle arrest.

JunB is a p73-regulated gene and inhibits cell proliferation by inducing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a (17). In our study, MP could significantly elevate p16INK4a and JunB mRNA levels. Any reason contributing to weakened p73 protein expression could impair JunB expression in myeloid cells (24). In previous reports, the drug hydroxyurea used for cancer therapy also induced the upregulation of JunB and c-jun in HeLa cells. The JunB target gene, tumor suppressor p16INK4a, was also upregulated by hydroxyurea in a JunB-dependent manner (25). Expression of JunB and p16INK4a mRNA was significantly upregulated after treatment. Whether the p73-JunB-p16 pathway was involved in cell cycle arrest requires further experimental investigation.

FOX transcription factors can induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cells. Fox transcription factors enhance the levels of various CKIs such as p27KIP1 and p21CIP1 in cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase. Its proapoptotic effect is mainly through transcriptional activation of proapoptotic genes including FasL, Bcl-6, and the BH3-only gene, Bim(26, 27).

Bim is one of the most potent proapoptotic BH3-only proteins. Bim is capable of directly activating Bax and Bak, which mediate the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, resulting in cell death (28). The upregulation of Bim mRNA may be associated with MP-induced apoptosis. A previous study suggested a novel role for p73 in the regulation of Akt-FKHR-Bim signaling and apoptosis (20). Further experimental investigations are needed to estimate the effect of p73 on the FKHR pathway in MP-induced cell death.

In conclusion, MP has shown cytotoxic activity on HeLa cancer cell lines by upregulating p27KIP1 and p73 proteins. Protein p73 may play a crucial role in this process by upregulating CKI gene expression such as p27KIP1 and p21CIP1 and regulating FKHR-Bim signaling. Therefore, MP shows potential use in the treatment of cervical cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#30901755), and the Scientific Research Program of HeBei Provincial Education Bureau (#2011107).

Footnotes

First published online July 30, 2013.

References

- 1.Yap TA, Workman P. Exploiting the cancer genome: strategies for the discovery and clinical development of targeted molecular therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:549–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pimentel MR, Molina G, Dionisio AP, Marostica MR, Junior, Pastore GM. The use of endophytes to obtain bioactive compounds and their application in biotransformation process. Biotechnol Res Int. 2011;2011:576286–576286. doi: 10.4061/2011/576286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer E, Hayat S, Atta ur R, Choudhary MI, Khan KM, Shah ST, et al. Efficient synthesis of isobenzofuran-1(3H)-ones (phthalides) and selected biological evaluations. Arzneimittelforschung. 2005;55:588–597. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee TF, Lin YL, Huang YT. Studies on antiproliferative effects of phthalides from Ligusticum chuanxiong in hepatic stellate cells. Planta Med. 2007;73:527–534. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phuwapraisirisan P, Rangsan J, Siripong P, Tip-Pyang S. New antitumour fungal metabolites from Alternaria porri . Nat Prod Res. 2009;23:1063–1071. doi: 10.1080/14786410802265415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suemitsu R, Ohnishi K, Morikawa Y, Nagatomo S. Zinnimidine and 5-(3′,3′-dimethylallyloxy)-7-methoxy-6-methylphthalide from Alternaria porri . Phytochemistry. 1995;38:495–497. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(94)00546-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang XL, Zhang S, Hu QB, Luo DQ, Zhang Y. Phthalide derivatives with antifungal activities against the plant pathogens isolated from the liquid culture of Pestalotiopsis photiniae . J Antibiot. 2011;64:723–727. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keyserling H von, Kuhn W, Schneider A, Bergmann T, Kaufmann AM. p16INK(4)a and p14ARF mRNA expression in Pap smears is age-related. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:465–470. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clybouw C, McHichi B, Mouhamad S, Auffredou MT, Bourgeade MF, Sharma S, et al. EBV infection of human B lymphocytes leads to down-regulation of Bim expression: relationship to resistance to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2005;175:2968–2973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Zhang H, Aravindakshan JP, Gotlieb WH, Sairam MR. Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic actions of a novel human and mouse ovarian tumor-associated gene OTAG-12: downregulation, alternative splicing and drug sensitization. Oncogene. 2011;30:2874–2887. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen R, Courtoy PJ, Jacobsen C, Dom G, Lima WR, Jadot M, et al. Endocytosis provides a major alternative pathway for lysosomal biogenesis in kidney proximal tubular cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5407–5412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700330104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farras R, Baldin V, Gallach S, Acquaviva C, Bossis G, Jariel-Encontre I, et al. JunB breakdown in mid-/late G2 is required for down-regulation of cyclin A2 levels and proper mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4173–4187. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01620-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammed KA, Wang X, Goldberg EP, Antony VB, Nasreen N. Silencing receptor EphA2 induces apoptosis and attenuates tumor growth in malignant mesothelioma. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:419–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Wang L, Wu D, Chen H, Chen Z, Thomas-Ahner JM, et al. Definition of a FoxA1 Cistrome that is crucial for G1 to S-phase cell-cycle transit in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6738–6748. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vervoorts J, Luscher B. Post-translational regulation of the tumor suppressor p27(KIP1) Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3255–3264. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebermann DA, Tront JS, Sha X, Mukherjee K, Mohamed-Hadley A, Hoffman B. Gadd45 stress sensors in malignancy and leukemia. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16:129–140. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.v16.i1-2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passegue E, Wagner EF. JunB suppresses cell proliferation by transcriptional activation of p16(INK4a) expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:2969–2979. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghavendra PB, Pathak N, Manna SK. Novel role of thiadiazolidine derivatives in inducing cell death through Myc-Max, Akt, FKHR, and FasL pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoica BA, Movsesyan VA, Lea PM, Faden AI. Ceramide-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with dephosphorylation of Akt, BAD, FKHR, GSK-3beta, and induction of the mitochondrial-dependent intrinsic caspase pathway. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:365–382. doi: 10.1016/S1044-7431(02)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin AR, Paul RK, Thakur VS, Agarwal ML. A novel role for p73 in the regulation of Akt-Foxo1a-Bim signaling and apoptosis induced by the plant lectin, Concanavalin A. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5617–5621. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kan WL, Cho CH, Rudd JA, Lin G. Study of the anti-proliferative effects and synergy of phthalides from Angelica sinensis on colon cancer cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besson A, Dowdy SF, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: cell cycle regulators and beyond. Dev Cell. 2008;14:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisso A, Collavin L, Del Sal G. p73 as a pharmaceutical target for cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:578–590. doi: 10.2174/138161211795222667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boominathan L. Some facts and thoughts: p73 as a tumor suppressor gene in the network of tumor suppressors. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:27–27. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yogev O, Anzi S, Inoue K, Shaulian E. Induction of transcriptionally active Jun proteins regulates drug-induced senescence. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34475–34483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgering BM, Kops GJ. Cell cycle and death control: long live Forkheads. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:352–360. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Tang N, Hadden TJ, Rishi AK. Akt, FoxO and regulation of apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1978–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiyama T, Dass CR, Choong PF. Bim-targeted cancer therapy: a link between drug action and underlying molecular changes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3173–3180. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]