Abstract

Background The prevalence of overweight and obesity is a rapidly growing threat to public health in both Morocco and Tunisia, where it is reaching similar proportions to high-income countries. Despite this, a national strategy for obesity does not exist in either country. The aim of this study was to explore the views of key stakeholders towards a range of policies to prevent obesity, and thus guide policy makers in their decision making on a national level.

Methods Using Multicriteria Mapping, data were gathered from 82 stakeholders (from 33 categories in Morocco and 36 in Tunisia) who appraised 12 obesity policy options by reference to criteria of their own choosing.

Results The feasibility of policies in practical or political terms and their cost were perceived as more important than how effective they would be in reducing obesity. There was most consensus and preference for options targeting individuals through health education, compared with options that aimed at changing the environment, i.e. modifying food supply and demand (providing healthier menus/changing food composition/food sold in schools); controlling information (advertising controls/mandatory labelling) or improving access to physical activity. In Tunisia, there was almost universal consensus that at least some environmental-level options are required, but in Morocco, participants highlighted the need to raise awareness within the population and policy makers that obesity is a public health problem, accompanied by improving literacy before such measures would be accepted.

Conclusion Whilst there is broad interest in a range of policy options, those measures targeting behaviour change through education were most valued. The different socioeconomic, political and cultural contexts of countries need to be accounted for when prioritizing obesity policy. Obesity was not recognized as a major public health priority; therefore, convincing policy makers about the need to prioritize action to prevent obesity, particularly in Morocco, will be a crucial first step.

Keywords: Obesity, Africa, policy, policy makers, decision making, stakeholders

KEY MESSAGES.

Finds that obesity is not recognized as a public health priority, even though 18% (Morocco) and 28% (Tunisia) of the adult population is obese.

Stakeholders in Morocco and Tunisia prefer ‘downstream’ options targeting individual behaviour change through education, rather than ‘upstream’ options aimed at changing the obesogenic environment.

Improving health literacy through health education may be a necessary stepping stone, to pave the way for the acceptance of measures that tackle the environment.

Highlights how priorities for obesity policy will depend on the socioeconomic, cultural, political and development context of the country. One size does not fit all.

Introduction

Over the last decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased in almost all parts of the world and is a rapidly growing threat to public health in both Morocco and Tunisia, where it is reaching similar proportions to high-income countries. In Morocco, 51% of adults >30 years were overweight in 2010, and 18% of obese (Ono et al. 2010) women are more affected by obesity than men and the gender gap is widening. In Tunisia, a similar trend in gender disparity is observed, but estimations are even higher as 62% of adults >30 years were overweight in 2010 and 28% obese (Ono et al. 2010).

Despite these figures, and the fact that obesity has important consequences on health, the economy and society, a national strategy for obesity does not exist in either country. In 2004, the World Health Assembly emphasized the importance of prevention, particularly in resource-poor contexts, which led to the adoption of the ‘Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health’ (WHO 2004) and a more recent action plan focusing on preventing non-communicable diseases (WHO 2008). In Morocco and Tunisia, like elsewhere, the underlying factors that influence the imbalance between food intake and physical activity are societal, and changes in the physical, economic, political, social and cultural environments to become more ‘obesogenic’ (Swinburn et al. 1999) are likely to be one of the main driving forces.

In high-income countries, strategies are often focused on educational and behavioural interventions that target individuals (Alvaro et al. 2011), which have been shown to be insufficient, especially for people living on a lower income (Link and Phelan 2005). There is large international consensus that multisectoral public health policy is needed to slow down the obesity epidemic (Chopra et al. 2002; Jebb et al. 2007; WHO 2008; Morris 2010). This will require a better balance, not only between interventions on an individual vs societal level but also between educational measures vs interventions that modify the environments that promote obesity. However useful, the large range of interventions proposed on an international level (WHO 2004, 2007, 2008, 2010) must also account for culture (Holdsworth et al. 2007), i.e. ‘the shaping of consciousness around food and physical activity’ (Lang and Rayner 2007) and the readiness of a population to accept policy initiatives.

It is acknowledged that the causes of overweight and obesity are multiple, requiring the participation and support of a range of key sectors and stakeholders, from government, health, agri-food industry, education, media, urban planning, NGOs, etc. (Millstone and Lobstein 2007; Snowdon et al. 2011). The co-ordination that needs to be accomplished is without precedent, and besides information on the effectiveness of different policies, governments also need to know which combination of these will initially meet with least resistance; this is why it is essential to seek the views of a broad range of stakeholders—including those involved both in producing environments that favour obesity and implementing preventive strategies. The need for researchers to focus attention on the policy-making process, as well as policy content, acknowledges the fact that deciding whether to embark on a given policy goes beyond its intrinsic value (Catford 2006). Such an approach has already been conducted in Europe (Millstone and Lobstein 2007) but not yet in a lower-income country, despite the enormous prevalence of obesity. The aim of the study was, therefore, to explore the perspectives of key stakeholders towards a range of policies targeting obesity prevention in Morocco and Tunisia, and thus to guide policy makers in their decision making on a national level.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was granted in Morocco (Faculty of Medicine, Rabat) and Tunisia (l’Institut National de Nutrition et de Technologie Alimentaire) in 2009 and by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Research for Development (IRD), France in 2009.

Using multicriteria mapping

Multicriteria mapping (MCM) (Stirling 2006) provides a tool for understanding stakeholders’ views to assist in the development of public policies. It acknowledges the uncertainty and conditionality of health policy (Stirling 2010) and resolves the simplistic polarizing of views that can evolve when looking for solutions to complex public health problems, such as obesity.

Using a computer programme called ‘MC Mapper’, quantitative and qualitative data were gathered during face-to-face interviews that were recorded and transcribed. MCM has a four-part structure (composed of choosing options, defining criteria, scoring options and weighting) providing information not only on how different options perform but also on why they perform the way they do (Stirling 2006). The criteria are the different factors that the interviewee has in mind when they choose between, or compare, the pros and cons of the policy, e.g. how effective it would be. When stakeholders score the different policy options they also record the reasons for these scores. This process allows us to understand how the wider context influences their judgements; therefore, MCM does not only map views on individual policy options but also the wider terrain in which these options would be implemented.

Choosing policy options

The 12 policy options (Table 1) were selected by both national teams, primarily based on those suggested by the WHO (2004) and from policies appraised in the European project ‘PorGrow’ that some of the authors participated in (Millstone and Lobstein 2007). When selecting policy options to include in the final list, the teams prioritized policy options that they believed could reasonably be implemented, including options that focused on changing the environment and individual behaviour. As a consequence, the team decided to exclude fiscal policy, such as taxation and subsidies because the national teams viewed these as so unacceptable that including them was seen as counterproductive to engaging stakeholders. The 12 options were grouped into five ‘clusters’ (Table 1) to organize and structure the analysis: those targeting physical activity; the supply or demand for food; increasing information; promoting education and training; and involving institutional reforms. The two national teams agreed to common clustering of the individual options in this way for comparability.

Table 1.

Grouping of option clusters

| Option cluster | Policy optionsa | |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise and physical activity-oriented | 3. Improve communal sports facilities | |

| 4. Change planning and transport policies | ||

| 12. Extend provision of physical activity at school | ||

| Modifying the supply of, and demand for, foodstuffs | 5. Provide incentives to caterers to provide healthier menus | |

| 6. Control the composition of processed food products | ||

| 10. Control sales of food, drinks and snacks in school | ||

| Information-related initiatives | 1. Require mandatory nutrition labelling on processed and packaged food | |

| 2. Control on food and drink advertising that targets children | ||

| Educational initiatives | 8. Improve training for health professionals in obesity care and prevention | |

| 9. Improve health education for the general public | ||

| 11. Include food and health in the school curriculum | ||

| Institutional reforms | 7. Reform agricultural policy to support nutritional targets |

aThese numbers represent the order in which they were presented to stakeholders and are also referred to in Figures 2–4.

Appraising policy options

An important and distinctive feature of the MCM technique as used in this study is that interviewees were asked to assign two performance scores to each option under each criterion. When judging individual options against criteria of their own choosing, interviewees provided both optimistic and pessimistic scores, enabling them to indicate uncertainty and conditionality in different contexts, i.e. the performance of particular options was frequently thought to depend on the ways in which they were to be interpreted and implemented. Optimistic scenarios, therefore, refer to the performance of an option in the most favourable conditions, whereas pessimistic ones refer to how an option might perform in the worst case scenario, which could be different forms of implementation, or between appropriate and inappropriate applications, as well as a range of contextual variabilities.

MC Mapper then generates a set of bar charts that indicate the overall relative performance of the options, as perceived by stakeholders. Quantitative data were used to compare overall national views of particular interest groups aggregated, whereas qualitative data shed light on the factors influencing the performance of different policies.

Choosing stakeholders

The aim was to select informants operating at the highest national level to represent their stakeholder group and to reflect a broad ‘envelope’ of relevant viewpoints. The selection of these individuals was informed primarily by their institutional affiliations so, when taken together, the resulting stakeholder groups can be expected to represent in some detail the main relevant dimensions in the policy debate. National teams used a snowball approach from key informants to identify key stakeholders.

Data were gathered from 82 participant stakeholders from a wide range of categories to ensure that a comprehensive envelope of views was mapped. During a project workshop, both national teams selected 36 stakeholder categories to be interviewed, representing institutions that have an important role to play in policy making, either directly or through networks of influence, based on those emerging from the workshop or suggested by the WHO (2004, 2007). Categories were combined for analysis into seven groups of ‘Perspectives’ (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants interviewed in Morocco and Tunisia and grouped into perspectives for analysis

| Perspectives (A-G) | Morocco n = 37 participants | Tunisia n = 45 participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Government | |||

| Ministry of Finance | 1 | 1 | |

| Ministry of Communication | 1 | 1 | |

| Ministry of Health | 3 | 3 | |

| Ministry of Interior | 1 | 1 | |

| Ministry of Youth and Sport | 1 | 1 | |

| Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries | 2 | 1 | |

| Ministry of Planning and Land | 1 | 1 | |

| Ministry of Social support/Family | 1 | 2 | |

| Ministry of Culture | 1 | – | |

| High Commission of Planning | 1 | – | |

| Ministry of Transport | – | 1 | |

| Ministry of Commerce | – | 1 | |

| Ministry of Industry and Technology | – | 1 | |

| Ministry of Education | – | 1 | |

| Ministry of Sustainable Development | – | 1 | |

| B. Agri-food industry | |||

| Agri-food industry | 1 | 1 | |

| Large retailers | 1 | 1 | |

| Public sector caterers | 1 | 2 | |

| Farmers | 2 | – | |

| C. Health professionals | |||

| Doctors specializing in obesity | 1 | 1 | |

| Private sector doctors | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary care doctors | 1 | 1 | |

| Primary care nurses | 1 | 1 | |

| Nutritionists/dietitians | 1 | 1 | |

| D. Education sector | |||

| Primary school teachers | 1 | 1 | |

| Secondary school teachers | 1 | 1 | |

| Private school teachers | 1 | – | |

| Universities | 1 | 1 | |

| E. Media | |||

| Advertisers | 1 | 1 | |

| Health journalists | |||

| Written press | 1 | 3 | |

| Women’s press | 1 | 2 | |

| Radio/TV | 1 | 4 | |

| F. Public interest NGOs | |||

| Consumers | 1 | 1 | |

| Health promotion, physical activity and sport | 1 | 2 | |

| Women’s association | 1 | 1 | |

| Children’s association | 1 | 1 | |

| G. Multilateral partners (WHO/UNICEF) | 2 | 2 |

Scoping and interviewing stakeholders

The individuals selected were approached by the national research teams to explain the aims and context of the project, negotiate any associated matters such as provisions for anonymity, and to secure their consent. The next step in the process was a ‘scoping interview’, in which the MCM approach was explained and queries dealt with concerning the project, the chosen topic or the basis for their engagement. Participants received each a small package of information, providing further background on the project, an outline of the method and a set of detailed definitions for each policy option.

Thirty-seven (Morocco) and 45 (Tunisia) interviews, representing 33 and 36 categories, respectively, were held; in Morocco, interviews could not be arranged with three of the government categories. Interviews lasting 2–3 h were conducted in 2009–10 by two senior level academics per country trained in the use of MCM, to ensure consistency and access to high level stakeholders.

Data entry and analysis

Grouping criteria into issues

For analysis, the criteria that interviewees introduced were clustered into groups, e.g. different aspects of ‘cost’ were grouped together. The criteria chosen by participants were classed into six groups (issues) to analyse the performance of options (Table 3).

Table 3.

Categories of criteria (grouped into issues)

| Issues | Individual criteria |

|---|---|

| I. Effectiveness in reducing obesity | Will it reduce/prevent obesity, sustainability, pertinence, reaches the right target groups, can be monitored and evaluated. |

| II. Other health benefits | Health gains (in addition to obesity reduction) including prevents diet-related NCDs, improves well-being and fitness. |

| III. Feasibility | Can it be implemented politically, technically, and in terms of legislation, human capacity and technically; co-operation of agencies, across departments and sectors, supported by parliament, etc. |

| IV. Social acceptability | Social, cultural and individual acceptability. |

| V. Cost | Costs or economic consequences resulting from implementing or rolling out the policy; either to the state, local authorities, health services or citizens. |

| VI. Benefits for society | Includes equity, reaches minority and vulnerable sub-populations. Positive effect on environment, gives citizen benefits, raises education, provides community facilities, empowerment, participation, democracy and mobilization (for social benefit). |

Results

Criteria used to appraise options

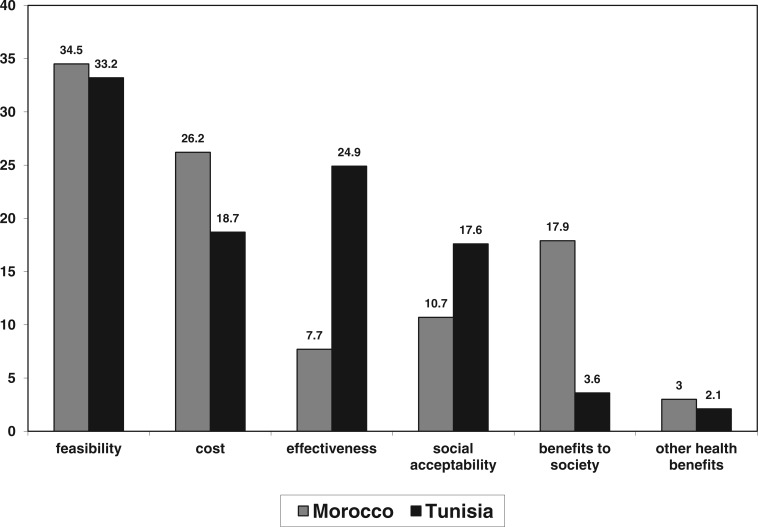

Criteria relating to feasibility and cost were chosen most often in Morocco, whereas feasibility and effectiveness in reducing obesity were selected mostly in Tunisia (Figure 1). But there was a lack of consensus between different stakeholder groups about the importance that they should be given. Stakeholders in all categories in both countries most frequently selected feasibility as a criterion, i.e. can it be done? However, the importance given to other categories of criteria varied according to stakeholder group; the government sector, health professionals, the education sector and NGOs in Morocco and the food industry in Tunisia subsequently emphasized cost. Whereas representatives of the media and multilateral partners (Morocco) and the education sector (Tunisia) were more concerned about societal benefits of policies. Only stakeholders in Tunisia from government, health professionals, media and NGOs emphasized the need to consider whether policies are actually effective in combating obesity.

Figure 1.

Proportion of criteria chosen (as percentages, grouped into issues).

Overall performance of options

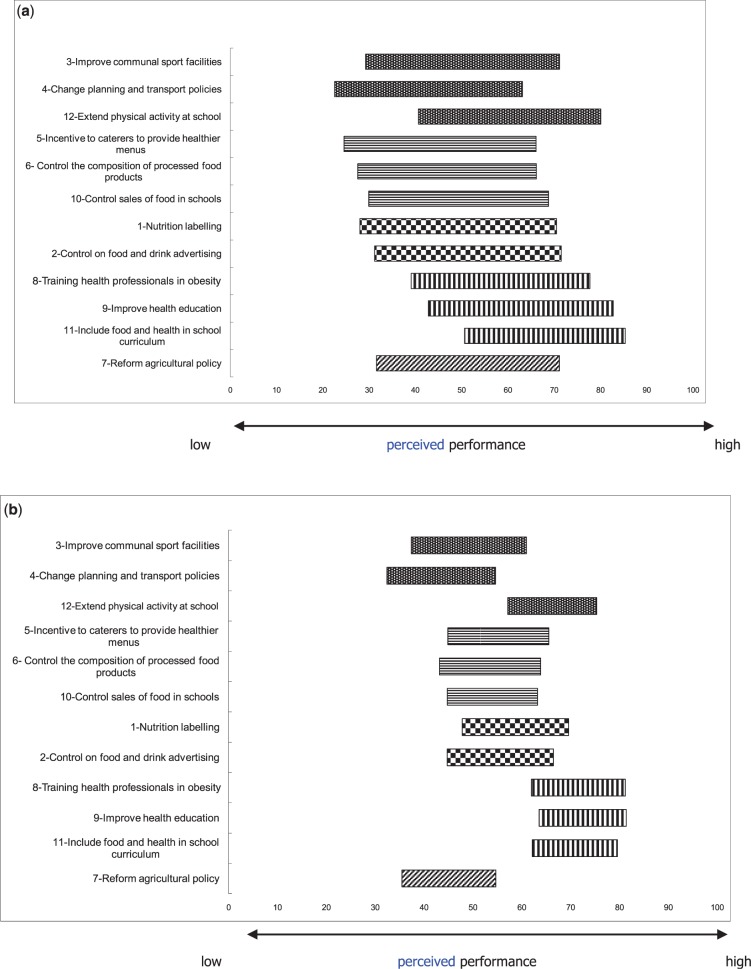

Figure 2a and b shows the averaged option rankings in clusters, indicating the preferences expressed by all Moroccan and Tunisian stakeholders. The bars are patterned according to the types of options (Table 2). The results shown are described below.

Figure 2.

Overall ranking of options by stakeholders (a) Morocco and (b) Tunisia. Please see Table 1 for the key to the groupings.

Morocco

Overall (Figure 2a), the three educational measures (training health professionals; health education for the general public; food in the school curriculum) and an option that targeted environmental change—‘Extend provision of physical activity at school’—were ranked most favourably of all; with much agreement between stakeholder groups. All these options were viewed as the most feasible and (with the exception of training health professionals) were seen as the measures that would be most effective in reducing obesity and proffer wider societal benefits.

All the other options that focus on changing the environment received positive scores under optimistic conditions (communal sports facilities; planning and transport policy; incentives to caterers; composition of processed food; food and drink sold in schools; mandatory nutrition labelling; food advertising reforms; agricultural policy reform); therefore, no option was rejected outright. Even so, a large degree of uncertainty was expressed about how they would perform under pessimistic conditions. Concern emerged from the qualitative data that the implementation and effectiveness of these policies was largely dependent on the socioeconomic, developmental, political and cultural context of Morocco, i.e. lack of funding, widespread illiteracy, complexity of legislation, inequality of access (geographical, gender, economic) and the strong influence of cultural norms whereby obesity/overweight is normalized for Moroccan women.

The options that target children were preferred in each cluster, i.e. nutrition in the school curriculum, physical activity at school, controlling advertising and controlling sales of food in schools. The performance of many options was seen as dependent on educational level (general literacy and health literacy), but stakeholders believed that their performance would only improve if the population was convinced that the problem of obesity exists in Morocco. Strong evidence from qualitative data in Morocco suggested that obesity was not recognized as a public health problem, and when its existence was acknowledged, it was not seen as a priority, for society or for public health.

Tunisia

Again (Figure 2b) the three educational measures were ranked most favourably (training health professionals; health education for the general public; food in the school curriculum); they were seen as the most feasible and (with the addition of extending provision of physical activity at school) were viewed as most effective in reducing obesity and the most socially acceptable. The first two measures (health education for the general public; food in the school curriculum) were seen as beneficial to society. All the other options that focus on modifying the environment received positive scores under optimistic conditions (communal sports facilities; incentives to caterers; composition of processed food; food and drink sold in schools; mandatory nutrition labelling; food advertising reforms). However, agricultural policy reform to support nutritional targets, and changing planning and transport policies performed poorly and were the two worst ranking options overall.

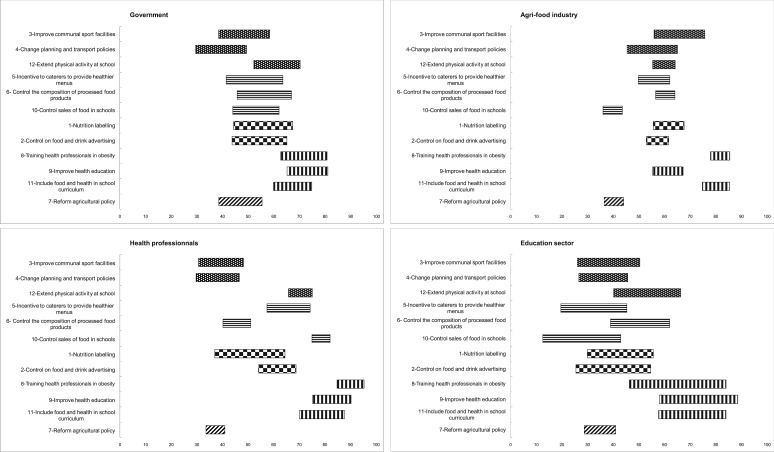

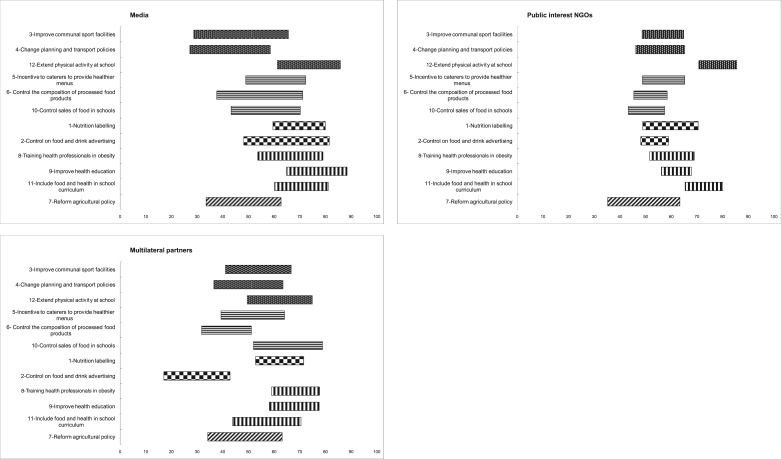

Views of different stakeholder groups

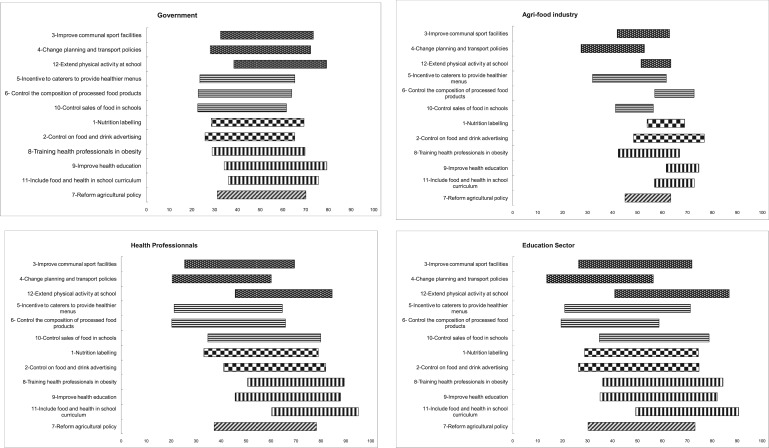

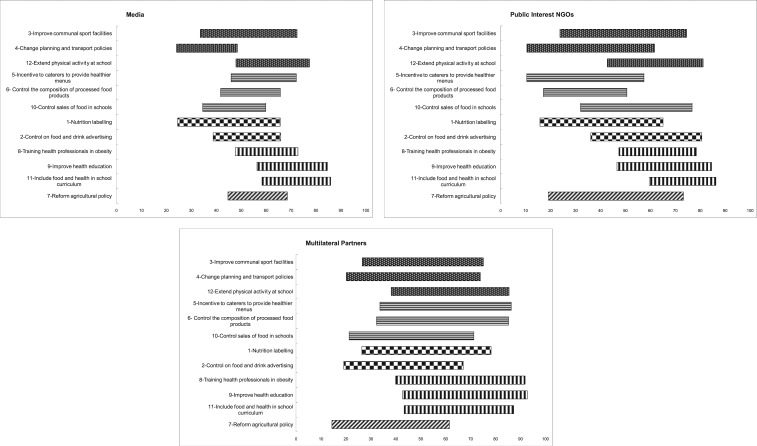

The mapping of different stakeholder groups showed very little disagreement between them in both Morocco (Figure 3a) and Tunisia (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Ranking of policy options by different stakeholder groups (Morocco).

Morocco

The three educational options finished almost always in the top three for all stakeholder groups, and the option promoting physical activity at school was supported by all, except the agri-food industry. There was also agreement for the options that did not perform well; changing planning and transport policy was ranked by most in the bottom three, except multilateral partners classed it in ninth position, and government, more optimistically, in seventh place. Instead, they ranked controlling advertising to children as their 11th and 12th ranking option, respectively. There was much consensus between stakeholders that reforming agricultural policy in line with nutritional guidelines was not a priority, with most ranking it in seventh or eighth position, except for multilateral partners who were even more pessimistic, ranking it in last position.

Tunisia

At least one of the three educational options finished in the top three of the list for all stakeholder groups, and the option promoting physical activity at school was supported by all stakeholder groups, and it was ranked lower only by the agri-food industry. Two stakeholder groups were less supportive of all three educational options; in fact media representatives ranked physical activity at school and controls on advertising in their top three, which was unexpected given the financial impact the latter could have on their industry. NGOs were the only group to rank nutrition labelling in their top three.

Figure 4.

Ranking of policy options by different stakeholder groups (Tunisia).

There was less agreement for the options that did not perform well; changing planning and transport policy was ranked by all in ninth position or worse, except for the agri-food industry and NGOs who were more optimistic, ranking it mid-way. There was much consensus between stakeholders that reforming agricultural policy in line with nutritional guidelines was not a priority, with most ranking it in last or second to last position, except for multilateral partners and NGOs who were slightly more optimistic.

The agri-food industry in Morocco showed the most support for options that could have financial consequences for them, i.e. improving composition of manufactured foods, controlling advertising and introducing nutritional labelling. On the other hand, the agri-food industry in Tunisia was reserved about policies that could have direct financial implications, i.e. improving composition of manufactured foods, sales of food in schools, reforming agricultural policy and controlling advertising did not perform well; however, they were more optimistic regarding nutritional labelling.

Discussion

The study was designed to provide an innovative form of social intelligence that was gathered by conducting intensive interviews with senior stakeholders employed in institutions that have some direct relevance to the problem of obesity and/or to policy measures under consideration. Unlike most other comparable approaches—both in the field of decision analysis and more widely—MCM is innovative as it focuses as much on ‘opening up’ as on ‘closing down’ a decision or policy process (Stirling 2008). This generates a rich body of information concerning the reasons for differing views and their practical implications for the overall performance of the selected options.

On this basis, it is possible to provide policy makers in Morocco and Tunisia with clear guidance as to the conditions under which a broad consensus can be assembled to appropriately respond to the challenge of obesity. No participant argued that any single option on its own would suffice, even though no one believed that solutions to the complex problem of obesity would be easy. Disagreements that did exist were between representatives within particular perspectives and between those perspectives.

The feasibility of policies (in practical or political terms) was seen as paramount in both countries, but whether a policy actually works was considered secondary to how much it costs in Morocco. However, the inverse was true in Tunisia, suggesting that the political landscape would be more receptive to the cost burden for preventing obesity in Tunisia, given it is looking beyond cost towards effectiveness in actually reducing obesity. The issue of cost is often paramount in policy making and is potentially unbearable for lower income countries (Lang and Rayner 2007).

Policy makers can also take up the opportunity to introduce policies that target childhood obesity prevention, which were widely supported in Morocco. Introducing nutrition into the school curricula and the practice of physical activity in schools were ranked in the top three options, as they were viewed as effective, feasible, acceptable and beneficial for Moroccan society; additionally, controlling sales of food and drink in schools was preferred of the options modifying offer and demand, whereas controlling food and drink advertising targeting children was ranked first of the information initiatives. Preventing childhood obesity through changing the school curriculum is widely accepted in Europe (Millstone and Lobstein 2007) for similar reasons as outlined in Morocco and Tunisia. One key reason that this option performed so well could be because it does not involve major frictions between stakeholders. There is some evidence that integrating nutrition into the school curriculum could be effective in preventing obesity in low- and middle-income countries, if combined with physical activity (Verstraeten et al. 2012).

There were numerous indications that the benefits of policy options often depended on the interactions amongst them, which raises the complex issue of how policy co-ordination can be achieved. A multisectoral approach may be best accomplished by creating a national obesity alliance in both countries, as national high-level leadership is identified as key if progress is to be made (Beaglehole et al. 2011; Pelletier et al. 2012). Such an alliance could facilitate a reflection on the policy options that would best reach women, who are by far the most affected. The different lifestyles and environments occupied by men and women in Morocco and Tunisia have led some to suggest that the roles played by women at home and in society explain, to a large extent, their higher prevalence of obesity (Batnitzky 2007). This highlights the need for the development of policies that also target the social and physical environments women occupy.

The findings of this study suggest that in Tunisia the problem of obesity is widely acknowledged by stakeholders from all sectors, and whilst there is interest in a range of options to combat obesity, those targeting individual level behaviour change through education are valued more by stakeholders than options that modify the ‘obesogenic’ environment, confirming results of a similar study conducted in Europe (Millstone and Lobstein 2007). Even though we acknowledge that education alone is insufficient, we argue that improving health literacy through health education may be a necessary stepping stone for societies in transition, to pave the way for the acceptance of measures that tackle the wider environment. Indeed others have acknowledged the need to provide information to the public initially to shift norms to legitimize policies that take a holistic approach (van Rijnsoever et al. 2011).

One of the major challenges for public policy is to find a better balance between measures that target individual behaviour change and policies that modify the environment that often conspires against behaviour change (Delpeuch et al. 2009; Alvaro et al. 2011). Raising awareness amongst policy makers about the convincing scientific evidence for the effectiveness of environmental level policy options will be a crucial first step in Tunisia. There was opposition to large scale action to influence behaviour involving changes to public policy that was not directly in the health sphere, even though on an international level it is widely recognized that many policies affecting health are developed and promoted in sectors outside of public health (Brownson et al. 2006; Pencheon et al. 2006; WHO 2008).

On the other hand, in Morocco the picture is quite different; policy makers and society still need convincing that obesity/overweight exist and are public health problems, which will require lobbying of policy makers and raising awareness of the general population. In addition, doubts were expressed in Morocco about the context in which they would be implemented, whether it be inequality of access (e.g. rural setting, poorer citizens, women), the need for legislation to ensure compliance or their acceptance by society. Creating political will is crucial to improve nutrition and health policy (Catford 2006; Pelletier et al. 2012) and researchers in both countries will need to take a proactive role in raising awareness, as personal contact between policy makers and researchers has been highlighted as one of the most important facilitators of moving research into policy (Brownson et al. 2006). Framing obesity as an economic development issue may also be a means to create political will (WHO 2008; Alwan et al. 2011), given the importance of economic cost and literacy to stakeholders in deciding obesity policy in Morocco and Tunisia.

Tunisia and Morocco represent two different socioeconomic and cultural contexts that should be accounted for when developing obesity policy. To garner the political support necessary to act, Moroccan stakeholders highlighted the need to address the fundamental issue of literacy (which it has begun to do), and raise awareness within both in the general population and in government and professional circles that obesity exists and is a public health problem. The context in Tunisia differs in that the population is mainly literate and more women have access to work and women have achieved a greater socioeconomic status; additionally Tunisia has a long history (since 1970) of a national nutrition institute which has been able to raise awareness regarding the obesity epidemic and the need for subsequent action.

Can the cultural shift necessary to recognize obesity as a public health priority be achieved in Morocco and Tunisia? Two political scientists (Kersh and Morone 2002) have shown that when societies find themselves confronting a problem of critical proportions, they will mobilize en masse and support the necessary policies, provided certain conditions are in place. First, the population at large must perceive that a problem exists and disapprove of it. This is manifestly not the case for obesity in Morocco and obesity is not recognized as urgent in Tunisia. Second, there must have been a steady build-up of scientific evidence detailing the harmful effects of the emergency, and assigning the responsibilities for it; and these scientific data must have been debated, acknowledged and accepted by society. This is becoming true for obesity in Tunisia, but still needs to develop further in Morocco. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the public must perceive there are innocent ‘victims’. This is perhaps where the preference of Moroccan stakeholders to focus on preventing childhood obesity may open a window of opportunity, because who is the quintessential victim, if not the child?

Conclusion

Whilst there is broad interest in a range of policy options, those measures targeting behaviour change through education were the most valued. The different socioeconomic, political and cultural contexts of Morocco and Tunisia need to be accounted for when prioritizing obesity policy. Obesity was not recognized as a major public health priority, therefore, convincing policy makers about the need to prioritize action to prevent obesity will be a crucial first step, particularly in Morocco.

Acknowledgements

We were able to conduct the ‘Obe-Maghreb’ project thanks to the engagement of the participants interviewed. The results discussed in this report are presented in a format true to the MCM methodology, and are therefore a consequence of this method, including its constraints. These results cannot, therefore, be taken as representing the official positions of the organizations in which the individuals interviewed work.

Funding

This work was supported by the CORUS (Coopération pour la recherche universitaire et scientifique) programme of the French Ministry of Overseas and European Affairs (Contract Corus 6028-2) and the Tunisian National Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology and the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement-IRD.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Alvaro C, Jackson LA, Kirk S, et al. Moving Canadian governmental policies beyond a focus on individual lifestyle: some insights from complexity and critical theories. Health Promotion International. 2011;26:91–9. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwan AD, Galea G, Stuckler D. Development at risk: addressing non-communicable diseases at the United Nations high-level meeting. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;89:546–546A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batnitzky A. Obesity and household roles: gender and social class in Morocco. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2007;30:445–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. The Lancet. 2011;377:1438–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Royer C, Ewing R, McBride T. Researchers and policymakers—travellers in parallel universes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:164–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catford J. Creating political will: moving from science to the art of health promotion. Health Promotion International. 2006;21:1–4. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dak004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra M, Galbraith S, Darnton-Hill I. A global response to a global problem: the epidemic of overnutrition. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2002;80:952–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpeuch F, Maire B, Monnier E, Holdsworth M. Globesity—A Planet Out of Control. London: Earthscan Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth M, Kameli Y, Delpeuch F. Stakeholder views on policy options for responding to the growing challenge from obesity in France: findings from the PorGrow project. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8(s2):53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jebb SA, Kopelman P, Butland B. Executive summary: foresight ‘Tackling Obesities: Future Choices’ project. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8(s1):vi–ix. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh R, Morone J. The politics of obesity: seven steps to government action. Health Affairs. 2002;21:142–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Rayner G. Overcoming policy cacophony on obesity: an ecological public health framework for policymakers. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8(s1):165–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. In: Policy Challenges in Modern Health Care. Chapel Hill: Rutgers University Press; 2005. Fundamental sources of health inequalities; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Millstone E, Lobstein T. Policy options for tackling obesity: what do stakeholders want? Obesity Reviews. 2007;8(s2):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Morris K. UN raises priority of non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2010;375:1859. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60855-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Guthold R, Strong K. Overweight and obesity prevalences. WHO global comparable estimates. World Health Organization Global Infobase. 2010 Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/infobase/Indicators.aspx, accessed 30 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Gervais S, et al. Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative. Health Policy and Planning. 2012;27:19–31. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencheon D, Guest C, Melzer D, Muir Gray JA. Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice. 2nd. Oxford: OUP; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon W, Potter JL, Swinburn B, et al. Prioritizing policy interventions to improve diets? Will it work, can it happen, will it do harm? Health Promotion International. 2011;25:123–33. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling A. Analysis, participation and power: justification and closure in participatory multi-criteria appraisal. Land Use Policy. 2006;23:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling A. Opening up or closing down: analysis, participation and power in the social appraisal of technology. Science, Technology & Human Values. 2008;33:262–94. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling A. Keep it complex. Nature. 2010;468:1029–31. doi: 10.1038/4681029a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29:563–70. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rijnsoever FJ, van Lente H, van Trijp HCM. Systemic policies towards a healthier and more responsible food system. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2011;65:737–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2011.141598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Lachat C, et al. Effectiveness of preventive school-based obesity interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;96:227–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.035378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_english_web.pdf, accessed 30 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. A Guide for Population-Based Approaches to Increasing Levels of Physical Activity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/PA-promotionguide-2007.pdf, accessed 30 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2008-2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of non-Communicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597418_eng.pdf, accessed 30 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Population-Based Strategies for Childhood Obesity: Report of the WHO Forum and Technical Meeting. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/child-obesity-eng.pdf, accessed 30 September 2012. [Google Scholar]