Abstract

Background:

Very elderly patients (75 years and older) with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) will be increasingly considered for cancer treatment as the population ages, but are underrepresented in clinical trials. Here we report outcomes of very elderly DLBCL patients treated in the modern era at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

Methods:

We queried the OHSU Tumor Registry for DLBCL cases treated since 2002. A total of 73 patients aged 75 years or older were analyzed under Institutional Review Board approval.

Results:

With a median follow up of 31 months, cause-specific survival was 58% and overall survival 51% at 3 years. Incorporation of an anthracycline did not influence outcomes. More than one extranodal site or poor-risk disease by Revised International Prognostic Index score were adversely prognostic, but pathologic features studied were not.

Conclusions:

Very elderly patients with DLBCL require prospective studies, which employ novel risk stratification and therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: elderly, DLBCL, prognosis

Introduction

With over 65,000 new cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) diagnosed annually in the USA, and an aging population, an increase in elderly NHL patients seeking medical care is anticipated [Jemal et al. 2010]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common NHL subtype in adults, and primarily affects elderly patients [The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project, 1997]. Modern data show a median age of DLBCL diagnosis of 70 years, and note that a quarter of all diagnoses occur in patients over 75 years, a rapidly growing age group [Smith et al. 2011]. Prior definitions of ‘elderly’ in DLBCL (particularly in reference to adults over 60 years of age) render historical clinical trial results irrelevant to modern, aging populations. In light of the paucity of data on the natural history, therapy, and outcomes in elderly DLBCL patients in the modern era, we conducted a study of ‘very elderly’ DLBCL patients, defined as those 75 years and older. In particular, the safety and efficacy of R-CHOP, the rate of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positivity and translocations involving Myc, and the utility of standard prognostic factors in this age group require further study. We chose to analyze overall survival (OS) and cause-specific survival (CSS) as primary endpoints to focus on lymphoma- and treatment-related deaths. To do so, we identified very elderly DLBCL patients diagnosed and treated at our institution in the chemoimmunotherapy era (2002–2012), and assessed baseline features, prognostic factors, and outcomes.

Material and methods

The Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) Tumor Registry was queried for all DLBCL cases treated since 2002. Those 75 years and older were selected for in-depth study under Institutional Review Board approval. Primary central nervous system lymphoma, unconfirmed diagnoses, and inadequate follow up for treatment or survival (no survival or disease status data available at least 3 months from end of therapy) were excluded from the in-depth analysis. Baseline clinical and pathologic features, i.e. immunohistochemical, EBV (EBV-encoded RNA [EBER]) staining, and translocations involving Myc and B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2), were recorded. Outcomes including relapse/progression, treatment failure, and death (with cause of death) were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier modeling. OS and CSS were analyzed from the date of diagnosis and were the primary focus of this analysis. CSS censored deaths unrelated to lymphoma or direct complications (occurring during or within 3 months) of first-line therapy. Cause of death was ascertained from medical charts contained in the OHSU system. Stage, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), performance status, disease bulk less than 10 cm, renal failure at diagnosis, initial treatment (R-CHOP versus nonanthracycline), and International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk factors were assessed for impact on CSS and OS using univariate analysis and log-rank testing with JMP statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The revised IPI (R-IPI) was calculated and categorized by Sehn and colleagues, with poor-risk patients having a score of 3 or higher [Sehn et al. 2007].

Results

Of 114 patients initially identified, 73 patients fitted the above criteria for detailed analysis. Median age was 82 years. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. With a median follow up of 31 months, 3-year CSS was 58% and OS 51% (Figure 1). A low proportion of biopsies tested were positive for EBV (3/23, by hybridization in situ for EBER). Most patients had early stage disease, with a high predilection for sinus/ear, nose and throat/orbit involvement. IPI factors were infrequently available on review, but when it could be calculated (n = 40), the R-IPI scores were 1–2 (good risk) in 21 patients, and 3–5 (poor risk) in 19 patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 73).

| Median age (range) | 82 (75–97) |

| % Female | 48% (35/73) |

| Germinal center B-cell subtype | 70% (34/50) |

| Median Ki67 (range) | 80% (< 5–100%) |

| B-cell lymphoma 6 positive | 78% (43/55) |

| Myc + B-cell lymphoma 2 rearrangement | 14% (3/21) |

| Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA positive | 14% (3/21) |

| Stage | I–II: 59% |

| III–IV: 41% | |

| Extranodal involvement; sinus/orbit/ear, nose and throat site | 58% (42/73) |

| 26% (20/73) | |

| Elevated lactate dehydrogenase | 43% (17/40) |

| Revised International Prognostic Index | Good: 21/40 (52%) |

| Poor: 19/40 (48%) |

Figure 1.

Cause-specific survival and OS among all patients. OS, overall survival.

R-CHOP, or R-EPOCH in one case, was given to 59% (43/73) of patients. During anthracycline chemotherapy, 4 patients died and 14 required a change to a different regimen due to toxicity. Three of these patients developed symptomatic cardiomyopathy during anthracycline therapy (3/43, 7%). Other systemic therapy was administered to 13 patients, and included R-CVP, R-CEOP, R-COPP, and single agent R with or without radiotherapy, and was selected at the discretion of the clinician. Remaining patients (n = 17) received only surgical resection, radiotherapy, or no received active lymphoma therapy, including six who were referred directly to hospice after diagnosis.

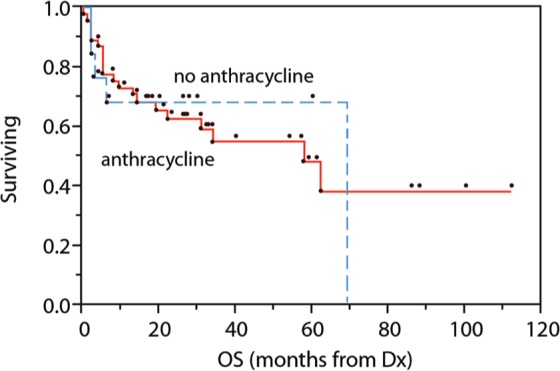

At follow up of 31 months, 39 deaths had occurred, 28 due to disease progression or relapse, or as a direct complication of therapy. Among six patients referred for palliative measures, the median survival was 4 months (range 0–13 months), and all deaths were due to lymphoma. R-IPI predicted CSS (p = .004) and OS (p = .01). The presence of more than one extranodal disease site also predicted poor CSS (p = .003). Ki67 index (> 80% versus less), cell of origin, and BCL6+ did not show prognostic impact. Similarly, stage, performance status, and LDH were not prognostic. Early stage (I–II) patients showed a trend toward improved CSS (65% CSS at 3 years versus 50% for advanced stage; p = .09). Finally, no difference was observed in outcomes between groups receiving anthracycline versus other systemic therapy; 68% versus 54% CSS at 3 years (p = not significant) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

OS among patients receiving systemic therapy, based on inclusion of anthracyclines. OS, overall survival.

Discussion

In this series of DLBCL patients with a median age of 82 years, we observed a 3-year CSS of 58% and OS 51% (Figure 1), but poor outcomes in those receiving palliative treatment alone. Frequent alteration from R-CHOP to nonanthracycline therapy (14/43) was observed, and four deaths occurred in the anthracycline group. The observed CSS of 58% at 3 years is nonetheless encouraging, given the advanced median age of this group. Given that life expectancy of an adult at age 82 years (the median age in this study) remains at 7.8 years [Centers for Disease Control, 2012], our data suggest that therapy with the goal of long-term survival is reasonable for very elderly DLBCL patients.

Pathologic features in this series included a low rate of EBV positivity (3/14) and ‘double-hit’ lesions (Myc and BCL2 rearrangements) (3/14). EBV-positive DLBCL has been linked with immunosenescence and advancing age primarily in DLBCL series from Asia [Park et al. 2007], but our data concur with those of Gibson and Hsi, which found EBV positivity by EBER uncommon among elderly DLBCL in the USA [Gibson and Hsi, 2009]. In addition, we observed only three cases of coincident Myc and BCL2 translocations. The interplay between age and infectious, environmental, and genetic determinants of lymphoma risk clearly requires further study.

Anthracyclines (and CHOP in particular) were proven to be a necessary component of elderly DLBCL therapy by randomized studies in the pre-rituximab era, but carry increased toxicity [Armitage and Potter, 1984; Sonneveld et al. 1995; Bastion et al. 1997]. In this study, anthracycline-containing therapy was associated with three cases of acute cardiomyopathy (occurring during treatment), and though numbers were small, was not associated with improved CSS or OS. Since it is likely that those not receiving anthracyclines constituted a more adverse group at baseline, the finding of similar outcomes to those receiving R-CHOP is somewhat surprising. However, group sizes were small and additional imbalances likely; further subgroup analysis was not performed. Another retrospective study of 476 DLBCL patients over 80 years found that R-CHOP also showed no OS benefit compared with nonanthracycline chemotherapy [Carson et al. 2012]. An epirubicin-containing regimen, with lower anthracycline dose intensity but inclusion of rituximab, produced similar response rates, event-free survival, and OS in a randomized study of DLBCL patients aged 65 years or older [Merli et al. 2012].

Similarly, investigators have recently tested reduced R-CHOP doses in elderly DLBCL patients, selecting the dose of chemoimmunotherapy based on age, geriatric assessment, and comorbidities [Spina et al. 2012]. In this study of 100 DLBCL patients aged 70 years or older, a complete remission rate of 81% was achieved, together with 5-year disease-free, OS, and CSS rates of 80%, 60%, and 74%. Only 4 out of 100 patients experienced treatment-related mortality. Another recent study of dose-reduced ‘mini-R-CHOP’ employed initial reductions of doxorubicin (25 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (400 mg/m2), and vincristine (1 mg), and standard rituximab (375 mg/m2), in treating 150 DLBCL patients over the age of 80 years [Peyrade et al. 2011]. The observed 2-year progression-free survival was 47%, and 12 toxic deaths were observed. Finally, in a study of 109 patients aged 70 years or older from Japan, the R-CHOP dose was reduced according to age (70% initial dose for patients in their 70s, 50% for those 80 years or older); this approach permitted 2-year OS rates of more than 60% with only five deaths related to therapy toxicity [Aoki et al. 2013]. These studies provide useful insight into further trial design, incorporating age as well as geriatric assessment and comorbidity, and constitute an increasing body of data suggesting that anthracycline dose may be attenuated in the chemoimmunotherapy era. While nonanthracycline strategies have been studied in a limited fashion (including bendamustine and rituximab [Weidmann et al. 2011], gemcitabine-oxaliplatin-rituximab [Fan et al. 2012]), it is not known whether these therapies afford durable responses or long-term cures in most patients.

Nonetheless, practice at our institution remains variable (mini-R-CHOP and nonanthracycline regimens are both employed, but geriatric assessment uncommonly performed). Randomized trials are needed to determine a new standard of care, and we suggest several considerations for their design. First, it is clear that lymphoma-related deaths remain a pressing problem in the first year after diagnosis even with anthracycline-containing chemoimmunotherapy, suggesting emphasis should remain on improving efficacy by incorporating new drugs. Second, biologic factors such as Ki67 or cell of origin were not useful in predicting outcomes or stratification of patients. Extranodal involvement and R-IPI, on the other hand, were prognostic and may be useful in risk-stratifying patients, potentially in conjunction with geriatric functional and comorbidity scores.

Limitations to our data include the heterogeneous therapy received, a relatively short follow-up period (median 31 months), and the possibility of bias in attribution of cause of death. Our series contained a large proportion of early stage patients, possibly related to referral patterns for institutional radiation oncology services or other reasons. A small number of patients receiving nonanthracycline therapy limited our ability to detect a potential difference in outcomes. Finally, R-CHOP dose intensity, growth factor support-use patterns, or standard response assessments were unavailable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while a preponderance of historical data supports CHOP at maximal doses in elderly DLBCL patients, a reassessment of dose intensity and the role of anthracyclines in the chemoimmunotherapy era are needed. Poor-risk, very elderly patients by the R-IPI define a priority group for further study. The use of geriatric scoring systems and comorbidities may prove useful in stratifying therapy in clinical trials of elderly DLBCL patients. While finding the balance between short-term efficacy and safety is a priority for this group, attention to morbidity and mortality occurring in the years after therapy will also be required, given increasing human longevity.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Stephen D. Smith, Department of Medicine, Division of Medical Oncology, University of Washington, 825 Eastlake Avenue E, G3-200, Seattle, WA 98109-1023, USA

Andy Chen, Center for Hematologic Malignancies, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Stephen Spurgeon, Center for Hematologic Malignancies, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Craig Okada, Hematology/Oncology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Guang Fan, Hematopathology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Jennifer Dunlap, Hematopathology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Rita Braziel, Hematopathology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Richard Maziarz, Hematopathology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

References

- Aoki K., Takahashi T., Tabata S., Kurata M., Matsushita A., Nagai K., et al. (2013) Efficacy and tolerability of reduced-dose 21-day cycle rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone therapy for elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage J., Potter J. (1984) Aggressive chemotherapy for diffuse histiocytic lymphoma in the elderly: increased complications with advancing age. J Am Geriatr Soc 32: 269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastion Y., Blay J., Divine M., Brice P., Bordessoule D., Sebban C., et al. (1997) Elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: disease presentation, response to treatment, and survival – a groupe d’etude des lymphomes de l’adulte study on 453 patients older than 69 years. J Clin Oncol 15: 2945–2953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson K., Lynch R., Riedell P., Roop R., Ganti A., Liu W., et al. (2012) Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients (pts) age 80 and older: analysis of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) National Database. American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting Abstracts 120: 968 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (2012) United States life tables 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports 61: 1–63 [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables.htm; last accessed 22 August 2012] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L., Wang L., Xu J., Zhang R., Wang R., Xu W., et al. (2012) Clinical phase II study of a non-anthracycline-based immunochemotherapy regimen (R-Gemox) as first-line treatment in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting Abstracts 120: 3667 [Google Scholar]

- Gibson S., Hsi E. (2009) Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphoma of the elderly at a United States Tertiary Medical Center: an uncommon aggressive lymphoma with a nongerminal center B-cell phenotype. Hum Pathol 40: 653–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., Ward E. (2010) Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 60: 277–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merli F., Luminari S., Rossi G., Mammi C., Marcheselli L., Tucci A., et al. (2012) Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and rituximab versus epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, prednisone and rituximab for the initial treatment of elderly “fit” patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the Anzinter3 Trial of the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Leuk Lymphoma 53: 581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Lee J., Ko Y., Han A., Jun H., Lee S., et al. (2007) The impact of Epstein-Barr virus status on clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 110: 972–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrade F., Jardin F., Thieblemont C., Thyss A., Emile J., Castaigne S., et al. (2011) Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-Minichop) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 12: 460–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehn L., Berry B., Chhanabhai M., Fitzgerald C., Gill K., Hoskins P., et al. (2007) The Revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-Chop. Blood 109: 1857–1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A., Howell D., Patmore R., Jack A., Roman E. (2011) Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer 105: 1684–1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneveld P., De Ridder M., Van Der Lelie H., Nieuwenhuis K., Schouten H., Mulder A., et al. (1995) Comparison of doxorubicin and mitoxantrone in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced diffuse non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma using CHOP versus CNOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 13: 2530–2539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina M., Balzarotti M., Uziel L., Ferreri A., Fratino L., Magagnoli M., et al. (2012) Modulated chemotherapy according to modified comprehensive geriatric assessment in 100 consecutive elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncologist 17: 838–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project (1997) Effect of age on the characteristics and clinical behavior of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Ann Oncol 8: 973–978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidmann E., Neumann A., Fauth F., Atmaca A., Al-Batran S., Pauligk C., et al. (2011) Phase II study of bendamustine in combination with rituximab as first-line treatment in patients 80 years or older with aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Ann Oncol 22: 1839–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]