Abstract

Exophiala dermatitidis is a dematiaceous fungus that is increasingly being identified as a cause of fungal infection especially in patients with immunodeficiency. To date, however, the factors predisposing E. dermatitidis and its optimal treatments have not been fully addressed. Here, we report the first patient with untreated multiple myeloma who developed E. dermatitidis pulmonary infection. We also review recent clinical reports describing the features of E. dermatitidis infection.

Keywords: Pulmonary infection, Exophiala dermatitidis, Multiple myeloma

1. Introduction

Exophiala dermatitidis (formerly Wangiella dermatitidis) is a dematiaceous fungus that is found in soil and dead plant material worldwide, and sometimes causes phaeohyphomycosis [1]. This fungus plays a significant role as a respiratory pathogen in patients with cystic fibrosis. It is also an increasingly common cause of systemic or visceral infection, particularly in patients with compromised immunity [2]. However, because E. dermatitidis infections are still relatively rare, the underlying risk factors remain unknown. Sporadic cases of systemic or visceral E. dermatitidis infection have been reported but, to our knowledge, no cases of E. dermatitidis infection associated with multiple myeloma have been reported. Here, we report a patient with untreated multiple myeloma who developed E. dermatitidis pulmonary infection. We also review recent clinical reports describing the features of E. dermatitidis infection.

2. Case

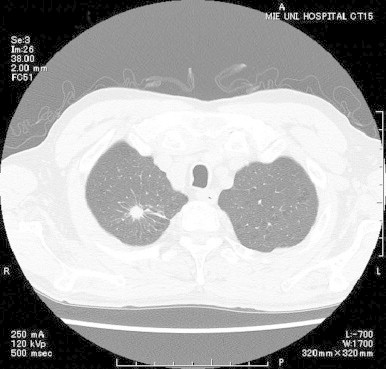

A 65-year-old man, whose medical history only included hypertension, developed back pain and was treated with pain relief medication by his primary care physician for 1 month. He had worked in the silviculture industry in rural areas for many years. Routine lumbar X-ray scans at day-14 revealed multiple compression fractures and the possibility of bone metastasis was strongly suspected. Therefore, he was referred to a central hospital. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest at day-10 revealed a solitary nodule with spicula, prompting suspicion of lung cancer (Fig. 1). Accordingly, he underwent bronchoscopic examination at day-7. Bronchioalveolar lavage (BAL) and biopsy did not detect any malignant findings, but a specimen sent for culture yielded a growth of black fungi. No other microorganisms were cultured from the specimen. For further investigation, he was referred to our hospital (day 0).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography of the chest at the initial visit. A solitary nodule with spicula was observed in the right upper lobe.

On examination, he appeared to be in good health, was afebrile, and had no symptoms other than back pain. The full blood count showed the following: leukocyte count, 6200/μL; hemoglobin, 9.5 g/dL; and platelet count, 213,000/μL. Peripheral blood smear revealed marked rouleaux formation. The biochemical profile was almost normal except for mild renal insufficiency (creatinine, 1.55 mg/dL) and elevated protein levels (total protein, 9.0 g/dL) with an IgGκ light chain monoclonal spike on protein electrophoresis. The C-reactive protein and 1,3-β-d glucan levels were 0.12 mg/dL and <3.7 pg/dL, respectively. A bone marrow aspirate showed that >20% of the total cell population were plasma cells. These findings, together with the evidence for monoclonal gammopathy and osteomyelitic lesion, resulted in the diagnosis of multiple myeloma (symptomatic myeloma).

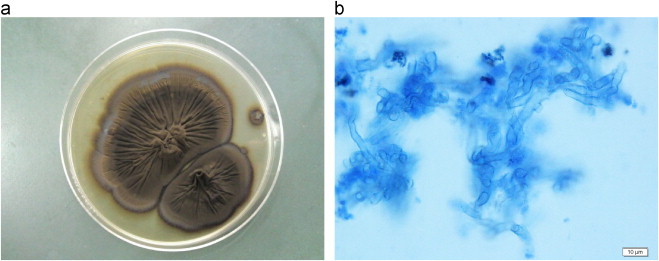

Subculture of the fungi obtained at the former hospital on Sabouraud agar produced large gray–black colonies with a wool-/cotton-like structure (Fig. 2a). Arcian blue staining and microscopic examination revealed the fungi had septate hyphae branching at acute angles (Fig. 2b). The segment of ribosomal DNA gene with internal transcribed spacer (ITS) was amplified from extraction of genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction methods using ITS1 and ITS4 primers and the isolate was finally identified as E. dermatitidis by sequencing of ribosomal DNA ITS region [3]. The obtained sequences were compared to all known sequences in the Genbank by use BLAST. It displayed over 99% sequence homologies in the ITS region with E. dermatitidis (Accession number JX473286.1). Therefore, the patient was ultimately diagnosed with E. dermatitidis pulmonary infection and multiple myeloma.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic and microscopic finding of the fungi obtained by the former hospital. (a) Subculture of the fungi on Sabouraud agar. Gray–black colonies with a wool-/cotton-like appearance were obtained. (b) Microscopic appearance of the specimen. Numerous fungal septate hyphae can be seen branching at acute angles (Arcian blue stain. Original magnification, ×200).

Antifungal susceptibility testing revealed that the minimum inhibitory concentrations of amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, minozazole, 5-fluorocytosine, and micafungin against this isolate were 2, >64, 2, 1, 1, 4, and >16 μg/mL, respectively. Therefore, he was initially treated with voriconazole (300 mg every 12 h on day 1 and then 200 mg every 12 h thereafter) for about 4 weeks (up to day +30). Despite this treatment, the size of lung lesion did not significant change on follow-up CT. Consequently, he underwent surgical resection of the lung lesion at day +37 to avoid possible clinical deteriorations caused by starting chemotherapy to treat the myeloma. Histopathologic examination and culture study of the surgical specimen confirmed E. dermatitidis infection. Following resection, he received steroid-based combined chemotherapy without relapse of infection, which achieved remarkable improvements in clinical findings in relation to the multiple myeloma.

3. Discussion

E. dermatitidis is a melanized yeast-like organism belonging to the dematiaceous family of fungi, which are ubiquitous in nature and are increasingly being recognized as a cause of human disease [1,2]. In humans, E. dermatitidis infections can be separated into three types: (1) superficial infections; (2) cutaneous and subcutaneous disease; and (3) systemic or visceral disease [4]. Superficial infections are often related to trauma or operation, whereas non-superficial infections generally occur in patients with predisposing factors. For example, an association with cystic fibrosis is well documented. However, because of the rarity of human infections, the definitive risk factors have not yet been established [5]. In a literature review of 37 patients with E. dermatitidis infections from 1960 to 1992 conducted by Matsumoto et al. [4], 19 had an associated disease or predisposing condition, and 20 had evidence of systemic disease, including 12 with fatal disseminated infections. To our knowledge, 30 cases, including our current case, were reported between 1993 and 2011 [2,5–32]. Of these, 24 (80%) had invasive (i.e., non-superficial) infections; these 24 cases are summarized in Table 1. Considering the cases reported to date, the incidence of E. dermatitidis infection is certainly increasing. As in the previous review [4], the majority of the invasive cases (17/24 cases; 71%) identified in the present review had predisposing factors, including peritoneal dialysis, leukemia, steroid use, human immunodeficiency virus infection, cancer, bronchiectasis, and diabetes mellitus. Changes in immune status can influence the progression of infectious disease, such as E. dermatitidis infection. However, an association between E. dermatitidis infection and multiple myeloma has not been described until now. Our case suggests that immunodeficiency caused by multiple myeloma may be a risk factor for invasive infection with E. dermatitidis.

Table 1.

Summary of cases with invasive/non-superficial Exophiala dermatitidis infection reported since 1993.

| No. | Age/sex | Manifestation | Predisposing factor | Diagnostic method | Treatment | Outcome | Region | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24/M | Brain abscess⁎ | None | Biopsy, culture | MCZ, 5-FC, AMPH-B, ketoconazole | Dead | Japan | Hiruma et al. [6] |

| 2 | 39/M | Peritonitis⁎ | Peritoneal dialysis | Culture | Catheter removal, FLCZ | Survived | Singapore | Lye [7] |

| 3 | 3/M | Fungemia⁎ | Acute leukemia | Culture | Catheter removal, AMPH-B, 5-FC | Survived | Germany | Blaschke-Hellmessen et al. [8] |

| 4 | 70/M | Brain abscess⁎ | None | Biopsy, culture | AMPH-B, Op | Dead | Singapore | Ajanee et al. [9] |

| 5 | 58/F | Phaeohyphomycosis | RA, steroid | Biopsy, culture | ITCZ, Op | Survived | UK | Woollons et al. [10] |

| 6 | 3/M | Fungemia⁎ | HIV infection | Culture | Catheter removal, AMPH-B, ITCZ | Survived | USA | Nachman et al. [11] |

| 7 | 28/M | Meningitis, brain abscess⁎ | None | Biopsy | AMPH-B, Op | Dead | Korea | Chang et al. [16] |

| 8 | 53/F | Peritonitis⁎ | Peritoneal dialysis | Culture | Catheter removal, FLCZ | Survived | Greece | Vlassopoulos et al. [17] |

| 9 | 29/F | Pneumonia⁎ | Cystic fibrosis | Culture | AMPH-B, ITCZ, VRCZ | Survived | Canada | Diemert et al. [18] |

| 10 | 62/M | Lymphadinitis | Acute leukemia | Biopsy, culture | AMPH-B, ITCZ | Survived | Taiwan | Liou et al. [19] |

| 11 | 39/F | Invasive stomatitis⁎ | Acute leukemia | Biopsy, culture, PCR | ITCZ, AMPH-B | Survived | Japan | Myoken et al. [20] |

| 12 | 55/F | Peritonitis⁎ | Peritoneal dialysis | Culture | Catheter removal, AMPH-B | Survived | UK | Greig et al. [21] |

| 13 | 58/F | Fungemia⁎ | Lung cancer | Culture | Catheter removal, AMPH-B | Survived | Taiwan | Tseng et al. [22] |

| 14 | 54/F | Pneumonia⁎ | Bronchiectasis | Culture | MCZ, nebulized AMPH-B | Survived | Japan | Mukaino et al. [2] |

| 15 | 54/F | Pneumonia⁎ | DM, systemic cancer | Biopsy, culture, PCR | FLCZ, ITCZ, AMPH-B | Dead | Netherlands | Tai-Aldeen et al. [24] |

| 16 | 81/F | Pneumonia⁎ | None | Biopsy, culture, PCR | FLCZ, ITCZ | Survived | Japan | Ozawa et al. [25] |

| 17 | 8/M | Systemic phaeohyphomycosis⁎ | None | Biopsy | AMPH-B, VRCZ | Dead | Turkey | Albaz et al. [26] |

| 18 | 3/M | Brain abscess, meningitis⁎ | None | Biopsy, culture, PCR | AMPH-B, FLCZ, ITLC | Dead | China | Chang et al. [27] |

| 19 | 11/F | Liver chirosis⁎ | None | Biopsy, culture, PCR | VRCZ, liver transplantation | Survived | Korea | Hong et al. [28] |

| 20 | 24/F | Systemic phaeohyphomycosis⁎ | None | Biopsy, culture, PCR | AMPH-B, VRCZ | Survived | Turkey | Oztas et al. [29] |

| 21 | 16/F | Pneumonia⁎ | Cystic fibrosis | Culture | ITCZ, VRCZ | NS | USA | Griffard et al. [30] |

| 22 | 86/F | Lung nodule⁎ | Dementia | Biopsy, culture | VRCZ | Survived | USA | Bulloch [5] |

| 23 | 17/M | Phaeohyphomycosis | None | Biopsy | ITCZ, Op | Survived | Argentine | Russo et al. [32] |

| 24 | 65/M | Lung nodule⁎ | Multiple myeloma | Biopsy, culture, PCR | VRCZ, Op | Survived | Japan | Our case |

Systemic or visceral disease. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; DM, diabetes mellitus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MCZ, miconazole; AMPH-B, amophotericin B; FLCZ, fluconazole; 5-FC, 5-fluorcytosine; Op, operation; ITCZ, itoraconazole; NS, not stated; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; VRCZ, voriconazole.

The route of infection is also obscure in most cases, usually because of the absence of identifiable cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions. It is possible that the fungus is either inhaled into the lungs with dust, or is ingested with food and enters the digestive tract, followed by retrograde passage into the biliary tract and the blood stream [29]. Central venous catheters also act as portals for fungal entry [8,11,22]. Additionally, this fungus was reported to be abundant in public steam baths and in water reservoirs, and a contaminated water supply was considered to be the most likely source of an Exophiala outbreak [26]. The present patient worked in silviculture, so it is possible that he was exposed to E. dermatitidis during the course of his employment. From these findings, it seems that the risk of infection may depend on the patient's history of contact with the fungus as well as the patient's immune status.

However, invasive E. dermatitidis infection occurred in several patients with no risk factors or known immunodeficiency [6,9,16,25–29,32]. Of the nine cases with no predisposing factors, eight were from Asian countries. Additionally, all four central nervous system infections reported to date occurred in Asia. This could imply that immunologic differences in the host or differences in exposure to the fungal propagules play a significant role in disease progression [25].

Another factor that should be considered is the overall prognosis. Indeed, 25% of the invasive cases (6/24) identified in our literature review were fatal. Based on these data and those reported in the earlier literature review [4], invasive E. dermatitidis infection is generally associated with a high mortality rate. However, comparing the two reports, it seems that the mortality rate has decreased over time, even for invasive infection, although not for central nervous system infection. Because of the rarity of this infection, no large-scale controlled studies have been done to examine the efficacy of specific antifungal agents. Nevertheless, newer antifungal agents and combination therapy may further improve the management of this disease [26,29]. Although clinical experience of treating this infection is relatively limited, recent reports, as well as our case, have documented beneficial effects of voriconazole in vitro [5]. Unsurprisingly, it is difficult to treat the infection after it has become fulminated, which means that appropriate therapy should be started as soon as possible. In previous report, the initial small localized lesions were amenable to surgical excision [26,29]. If central venous catheter was inserted, it should be removed to prevent systemic infection [21]. In the present patient, because the lung lesion did not change in size after treatment with voriconazole for 1 month and he needed prompt chemotherapy to treat his multiple myeloma, we opted for surgical resection of the lesion, based on the previous reports [26,29]. In general, hematologic malignancies require highly immunosuppressive therapy. Steroids are a key component of the treatment regimen for lymphoid neoplasms, including multiple myeloma. Therefore, surgical resection or debridement with antifungal agents is strongly recommended to prevent disseminated disease.

In conclusion, this is the first reported case of pulmonary E. dermatitidis fungal infection in a patient with multiple myeloma. This report should increase the awareness of E. dermatitidis, particularly its pathogenicity, in immunodeficient patients. With the more frequent use of immunosuppressive agents, the incidence of E. dermatitidis infection is likely to increase. Although the optimal treatment remains unknown, the cases accumulated to date indicate that appropriate antifungal therapy, surgical debridement, and careful immunological interventions are necessary for a positive outcome. Because of the high mortality rate, it is vital that this still life-threatening fungal infection is promptly diagnosed and treated.

Conflict of interest

There are none.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hajime Fujimoto at Mie Chuo Medical Center, Tsu, Mie, Japan, and all the staff in the Department of Hematology and Oncology, Tsu, Mie, Japan, for their contributions to the article.

References

- 1.Kantarcioglu A.S., de Hoog G.S. Infections of the central nervous system by melanized fungi: a review of cases presented between 1999 and 2004. Mycoses. 2004;47:4–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukaino T., Koga T., Oshita Y., Narita Y., Obata S., Aizawa H. Exhophiala dermatitidis infection in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respiratory Medicine. 2006;100:2069–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White T.J., Burns S., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplication and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press Inc;; New York: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto T., Matsuda T., McGinnis M.R., Ajello L. Clinical and mycological spectra of Wangiella dermatitidis infections. Mycoses. 1993;36:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1993.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulloch M.N. The treatment of pulmonary Wangiella dermatitidis with oral voriconazole. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2011;36:433–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiruma M., Kawada A., Ohata H., Ohnishi Y., Takahashi H., Yamazaki M. Systemic phaeohypomycosis caused by Exophiala dermatitidis. Mycoses. 1993;36:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1993.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lye W.C. Peritonitis due to Wangiella dermatitidis in a patient on CAPD. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 1993;13:319–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaschke-Hellmessen R., Lauterbach I., Paul K.D., Tintelnot K., Weissbach G. Detection of Exhophiala dermatitidis (Kano) De Hoog 1997 in septicemia of a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and in patient with cystic fibrosis. Mycoses. 1994;37:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajanee N., Alam M., Holmberg K., Khan J. Brain abscess caused by Wangiella dermatitidis: case report. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;23:197–198. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woollons A., Darley C.R., Pandian S., Arnstein P., Blackee J., Paul J. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Exophiala dermatitidis following intra-articular steroid injection. British Journal of Dermatology. 1996;135:475–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nachman S., Alpan O., Malowitz R., Spitzer E.D. Catheter-associated fungemia due to Wangiella (Exophiala) dermatitidis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996;34:1011–1013. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.1011-1013.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerard C., Duchesne B., Hayette M.P., Lavalleye B., Marechal-Coutois C. A case of Exhophiala dermatitidis urceration. Bulletin de la Societe Belge d'Ophtalmologie. 1998;268:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hata Y., Naka W., Nishikawa T. A case of melanonychia caused by Exophiala dermatitidis. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;40:231–234. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.40.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerkmann M.L., Piontek K., Mitze H., Haase G. Isolation of Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis in a case of otitis externa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1999;36:241–247. doi: 10.1086/520467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banaoudia F., Assouline M., Pouliquen Y., Bouvet A., Gueho E. Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis keratitis after keratoplasty. Medical Mycology. 1999;37:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang C.L., Kim D.S., Park D.J., Kim H.J., Lee C.H., Shin J.H. Acute cerebral phaeohyphomycosis due to Wangiella dermatitidis accompanied by cerebrospinal fluid eosinophilia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38:1965–1966. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1965-1966.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlassopoulos D., Kouppari G., Arvanitis D., Papaefstathiou K., Dounavis A., Velegraki A. Wangiella dermatitidis peritonitis in a CAPD patient. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 2001;39:2261–2266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diemert D., Kunimoto D., Sand C., Rennie R. Sputum isolation of Wangiella dermatitidis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;33:777–779. doi: 10.1080/003655401317074644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liou J.M., Wang J.T., Wang M.H., Wang S.S., Hsueh P.R. Phaeohyphomycosis caused by Exophiala species in immunocompromised hosts. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2002;101:523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myoken Y., Sugata T., Fujita Y., Kyo T., Fujihara M., Katsu M. Successful treatment of invasive stomatitis due to Exophiala dermatitidis in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 2003;32:51–54. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greig J., Harkness M., Taylor P., Hashmi C., Liang S., Kwan J. Peritonitis due to the dermatiaceous mold Exophiala dermatitidis complicating continuous amubulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2003;9:713–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tseng P.H., Lee P., Tsai T.H., Hsueh P.R. Central venous catheter-associated fungemia due to Wangiella dermatitidis. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2005;104:123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastel S.R., Hammersmith K.M., Rapuano C.J., Cohen E.J. Exophiala dermatitidis keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 2006;32:681–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tai-Aldeen S.J., El Shafie S., Alsoub H., Eldeeb Y., de Hoog G.S. Isolation of Exophiala dermatitidis from endotracheal aspirate of a cancer patient. Mycoses. 2006;49:504–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozawa Y., Suda T., Kaida Y., Kato M., Hasegawa H., Fujii M. A case of bronchial infection of Wangiella dermatitidis. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;45:907–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albaz D., Kiber F., Arikan S., Sancak B., Celik U., Aksaray N. Systemic phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala (Wangiella) in an immunocompetent child. Medical Mycology. 2009;47:653–657. doi: 10.1080/13693780802715815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang X., Li R., Yu J., Bao X., Qin J. Phaeohyphomycosis of the central nervous system caused by Exophiala dermatitidis in a 3-year-old immunocompetent host. Journal of Child Neurology. 2008;24:342–345. doi: 10.1177/0883073808323524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong K.H., Kim J.W., Jang S.J., Yu E., Kim E.C. Liver cirrhosis caused by Exophiala dermatitidis. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58:674–677. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.002188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oztas E., Odemis B., Kekilli M., Kurt M., Dinc B.M., Parlak E. Systemic phaeohyphomycosis resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis caused by Exophiala dermatitidis. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58:1243–1246. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.008706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffard E.A., Guajardo J.R., Cooperstock M.S., Scoville C.L. Isolation of Exophiala dermatitidis from pigmented sputum in a cystic fibrosis patient. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2010;45:508–510. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park K.Y., Kim H.K., Suh M.K., Seo S.J. Unusual presentation of onychomycosis caused by Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2011;36:418–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo J.P., Raffaeli R., Ingratta S.M., Rafti P., Mestroni S. Cutaneous and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis. SKINmed. 2010;8:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]