Abstract

Introduction

Resistance of cancer stem/progenitor cells (CSPCs) to chemotherapy can lead to cancer relapse. Ovarian teratocarcinoma (OVTC) arises from germ cells and comprises pluripotent cells that can be used to study cancer cell stemness. In this study, we evaluated whether microRNA-21 (miR-21) promotes ovarian teratocarcinoma by maintaining cancer stem/progenitor populations.

Methods

The lentiviral delivery system was used to upregulate or to suppress the expression of miR-21 in the human ovarian teratocarcinoma cell line PA1 and cell growth assays were used to monitor the expression of miR-21 at different time points. Antibodies directed toward CD133, a stem cell marker, were used to identify CSPCs in the PA1 cell population, and the level of miR-21 expression was determined in enriched CSPCs. Stem cell functional assays (sphere assay and assays for CD133 expression) were used to assess the effects of miR-21 on progression of the CD133+ population.

Results

Knockdown of miR-21 in PA1 cells attenuated growth of PA1 cells whereas overexpression of miR-21 promoted cell growth. Moreover, knockdown of miR-21 resulted in a marked reduction in the CD133+ population and sphere formation of CSPCs. In contrast, overexpression of miR-21 resulted in a marked increase in the population of CD133+ cells as well as sphere formation of CSPCs.

Conclusions

MicroRNA-21 plays a significant role in cancer growth by regulating stemness in cancer cells.

Keywords: microRNA 21, Ovarian teratocarcinoma, Cancer stem/progenitor cells, CD133

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-coding RNAs (22 to 24 nucleotides in length) that negatively regulate post-transcription by binding to the 3′UTR of target messenger RNA [1-4]. Studies have shown that miR-21 functions as an onco-miR by regulating tumorigensis and tumor progression [5-7] and has been found to be frequently up-regulated in cancer stem/progenitor cells (CSPCs) [8-11]. Several studies have demonstrated that knockdown of miR21 inhibits cell proliferation, migration and tumor growth in breast [12-14] and ovarian cancers [15,16]. Furthermore, some reports have shown that up-regulation of miR-21 maintains self-renewal and pluripotency of CSPCs and also regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer stem-like cells [17,18]. However, it is still unclear whether miR-21 promotes cancer by maintaining the pluripotency of stem or progenitor cells.

Ovarian cancer can be grouped by cellular origin, including epithelial cells (ovarian carcinoma), stromal cells (ovarian adenoma) and germ cells (ovarian teratoma and teratocarcinoma (OVTC)) [19,20]. OVTC is a rare, malignant neoplasm consisting of elements of teratoma with those of embryonal carcinoma or choriocarcinoma [21-25]. OVTC is caused by the abnormal development of pluripotent germ and embryonic cells, making it a good model for studying the behavior of CSPCs.

CSPCs are thought to be a confounding factor for tumor recurrence and chemoresistance because of their capacity for unlimited self-renew and differentiation [19,26-29]. Studies have shown that several glycoproteins, namely CD133, CD117, CD24 and CD44, as well as the transcription factors OCT-4 and Nanog are markers of CSPCs [30-34]. CD133 is abundantly expressed in the human OVTC cell line PA1 and is frequently used to enrich CSPCs in studies of cancer stem cell characteristics. In addition to measuring CSPCs markers, tumor sphere formation is also used to detect and enrich CSPCs [19,27].

Recently, lentiviral-based miRNAs delivery systems (antisense-miRNAs to knockdown, or pre-miRNAs to overexpress) were developed to manipulate miRs expressions in cells. By introducing MiRZip-21 microRNA (knockdown) and pre-miR-21 (overexpression), we established a durable and effective miR-21 manipulation method [35,36]. In this study, lentiviral-based miR-21 modulators were used to examine the role of miR-21 in OVTC cells.

Methods

Cell culture

The human OVTC cell line PA1 and the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T were cultured in ((D)MEM) (Gibco, USA) with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, USA). PA1 cells were provided courtesy of >Dr. Min-Chie Hung (MD Anderson, Houston, TX, USA) and HEK293T cells were obtained from Dr. Yuh-Pyng Sher (Center of Molecular Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan). The cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Western blotting assay

Protein extraction and the immunoblot assay were performed as previously described [37]. Briefly, cells were washed with 1 x PBS and resolved in RIPA buffer (100 mM Tris, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 5% NP40; pH8.0) with protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blocking of non-specific binding was accomplished by adding 5% non-fat milk. After application of primary antibodies, secondary antibodies were applied (1:3,000, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-goat-anti-mouse and HRP-goat-anti-rabbit) for one hour at room temperature. Signals were enhanced using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts 01821, USA) and detected by ChemiDoc ™ XRS + (BioRad, Hercules, CA 94547).

Transfection and infection procedure

Basically, the lentiviral production and infection procedures were carried out as reported previously [38]. Briefly, cells were transfected with the following lentivirus plasmids: psPAX2 packaging plasmid, pMD2G envelope plasmid (Addgene, Cambridge MA 02139) [37,38], miRZip-21 [35] (anti-miR-21 microRNA construct; System Biosciences, SBI, Johnstown, PA 15901, USA), and hsa-miR21 [36] (Human Lentiviral Primary microRNA Over-Expression Construct in pMIRNA1; System Biosciences, SBI). Both lentiviral plasmids carried the GFP gene and were co-transfected with psPAX2 and pMD2G into HEK293T cells at a ratio of 3:2:4 by lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. After six hours, the medium was replaced with fresh (D)MEM/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) medium and cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Medium containing virus was collected by centrifugation and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. Medium containing 0.8 mg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was then added to culture dishes containing 106 PA1 cells. After 16 hours of infection, the medium containing virus was replaced with fresh (D)MEM/10% FBS medium and cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Infected cells were then collected and analyzed. The GFP+ cells were measured by flow cytometry (BD LSR II Flow Cytometry) to determine infection efficiencies. GFP + cells with infection efficiencies greater than 85% were subjected to the following experiments (data not shown).

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was extracted from PA1 cells as reported previously [37]. Briefly, cells that had reached approximately 80% to 90% confluence in 100-mm dishes were lysed with 1 ml Trizol (Invitrogen). Phenol/chloroform was then added and RNA-rich layers were separated by centrifugation. Soluble RNA was precipitated with 2-propanol. RNA was then rinsed with 75% ethanol and dissolved in RNase-free water. For first-strand cDNA synthesis, 5 μg of total RNA was used to perform reverse transcription PCR by the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Bio Inc., Tokyo, Japan). MiRNA cDNA was synthesized using the Mir-X™ miRNA First-Strand synthesis Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA). cDNA and miRNA were synthesized according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

A real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and the KAPA™ SYBR FAST One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA, USA) were used according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Relative gene expression was determined by normalizing the expression level of the target gene to the expression level of housekeeping genes (U6 or actin). Threshold value (Ct) dynamics were used (2-ΔΔCt) for quantitation of gene expression. The qRT-PCR primer sequences were as follows: CD133 forward 5′- TCT CTA TGT GGT ACA GCC G-3′, reverse 5′- TGA TCC GGG TTC TTA CCT G-3′; CD24 forward 5′- TTT ACA ACT GCC TCG ACA CAC ATA A-3′, reverse 5′- CCC ATG TAG TTT TCT AAA GAT GGA A-3′; CD44 forward 5′- GAC CTC TGC AAG GCT TTC AA-3′, reverse 5′- TCC GAT GCT CAG AGC TTT CTC-3′; CD117 forward 5′- CAA GGA AGG TTT CCG AAT GC-3′, reverse 5′- CCA GCA GGT CTT CAT GAT GT-3′; Nanog forward 5′- GGG CCT GAA GAA AAC TAT CCA TCC-3′, reverse 5′- TGC TAT TCT TCG GCC AGT TGT TTT-3′; OCT-4 forward 5′- GGC CCG AAA GAG AAA GCG AAC C-3′, reverse 5′- ACC CAG CAG CCT CAA AAT CCT CTC-3′; SCF forward 5′- ACT GAC TCT GGA ATC TTT CTC AGG-3′, reverse 5′- GAT GTT TTG CCA AGT CAT TGT TGG-3′; miR-21 5′- TAGCTTATCAGACTGATGTTGA-3′.

Cell growth analysis

The WST-1 assay (Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana 46250, USA) [39] was used to assess cell growth. Briefly, 103 cells/100 μl/well were seeded in 96-well plates with (D)MEM in 10% FBS and were incubated for the designated time periods (one, two, four, six and eight days). Then 10 μl of WST-1 solution was added to each well and cells were allowed to incubate at 37°C in an incubator for one hour. Cell viability was quantified by colorimetric detection in an ELISA plate reader (Beckman Coulter Paradigm™ Detection Platform, USA) at an absorbance of 450 nm and 690 nm to generate an optical density (OD) proportional to the relative abundance of live cells in the given wells.

Verification and sorting of CD133+ cells

Cells were detached with 1% trypsin/EDTA and cell membrane non-specific binding to antibodies was blocked by 5% BSA for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with antibody CD133- allophycocyanin (APC) (magnetic cell separation (MACS), Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA 95602) for 30 minutes and then subjected to flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), BD FACSAria, USA) analysis. The CD133+/− cells were collected by a cell sorter (BD FACSAria).

Sorting of CD133+ and CD133– populations

A CD133 MicroBead kit (Miltenyi Biotec) was used to sort PA1 CD133+ cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 108 cells were washed, resuspended in 300 μl of buffer (1 X PBS/ pH 7.2, 0.5% BSA/2 mM EDTA), with 100 μl FcR Blocking Reagent and 100 μl of CD133 MicroBeads, mixed well, and then incubated for 30 minutes at 2°C to 8°C. The labeled cells were then washed, resuspended in 500 μl buffer and applied on a MACS Column of MiniMACS separation kit to collect the unlabeled negative fraction (that is, CD133– cells). Finally, we moved the column onto collection tubes to collect labeled cells (that is, CD133+ cells).

Sphere formation assay

Cells were collected and washed to remove serum and then suspended in serum-free (D)MEM supplemented with 20 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor (hrEGF), 10 ng/ml human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (hrbFGF), 5 μg/mL insulin and 0.4% BSA (Sigma). The cells were subsequently cultured in ultra low attachment 6-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at a density of less than 5,000 cells/well for 14 days. Spheres were observed under a microscope and images were photographed under a phase contrast fluorescence microscope (Nikon, ECLIPSE 80i).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Student’s t-test. All experiments were repeated at least three times, and P-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

MiR-21 is essential for PA1 cell growth

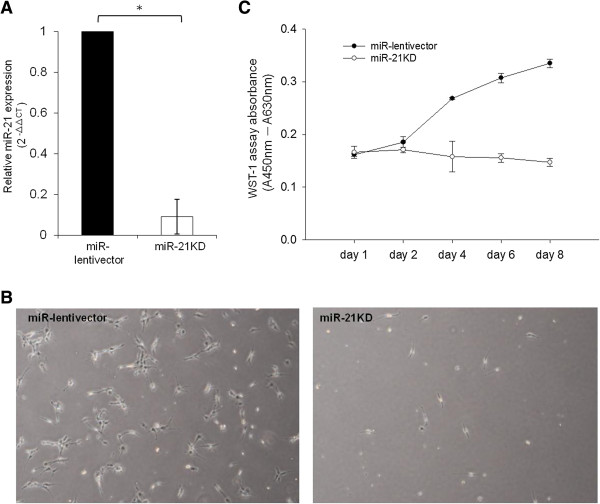

Knockdown of miR-21 has been shown to inhibit cell growth in ovarian cancer in vitro [15,16]. To assess whether miR-21 affects cell growth in OVTC, we used the lentiviral delivery system to optimize miRZip-21 constructs. We found that miRZip-21 reduced miR-21 expression levels by 85% in PA1 cells (Figure 1A). We measured the effects of miR-21 knockdown on PA1 cell growth at days one, two, four, six and eight and found that cell numbers had diminished at day six of culture (Figure 1B). As seen in Figure 1C, cell growth was abolished by miR-21 knockdown during all measurement time points. These data suggest that miR-21 is essential for OVTC PA1 cell growth, a finding consistent with that reported in previous studies [12-16].

Figure 1.

Knockdown of miR-21 inhibits PA1 cell growth. MiR-21 expression was significantly lower in PA1 cells infected with anti-miR-21 (miR-21 KD) than in cells infected with control (miR-lentivector) constructs. Relative expression of miR-21 was detected with quantitative real-time PCR and the relative amount of miR-21 is presented as the values of 2-ΔΔCt(A). Cell morphology and confluence of vector- or anti-miR-21-infected PA1 cells. Images were photographed on the sixth day of culture using a phase contrast fluorescence microscope (40×) (B). Cell growth WST-1 assays were performed at the indicated time points (one, two, four, six and eight days) and are shown on the X-axis. The Y-axis indicates the absolute absorbance (Abs.) values (Abs. at 450 nm deducted from Abs. at 630 nm background readings). The results shown are from three reproducible experiments (C). * indicates significance at P values less than 0.05. miR, microRNA.

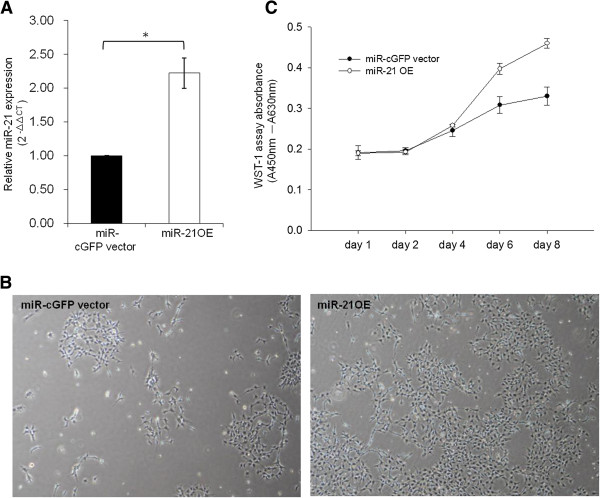

Exogenous delivery of miR-21 promotes PA1 cell growth

In order to confirm that miR-21 promotes cell growth, hsa-miR21 plasmids (miR-21 overexpression constructs) were introduced to overexpress miR-21 in PA1 cells. In our delivery system, miR-21 expression levels were approximately twice as great as those in the vector control (Figure 2A). As expected, PA1 cells treated with pre-miR-21 had higher growth capacity compared to vector control delivery at day four (Figure 2B). As seen in Figure 2C, cell growth was enhanced by miR-21 overexpression during all measurement time points. This result is consistent with the data presented in Figure 1. The results indicate that miR-21 is essential for PA1 cell growth.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of miR-21 promotes PA1 cell growth. MiR-21 expression was significantly higher in PA1 cells infected with pre-miR-21 (miR-21 OE) than in cells infected with control (miR-cGFP vector) constructs. Relative expression of miR-21 was detected with quantitative real-time PCR and the relative amount of miR-21 is presented as the value of 2-ΔΔCt(A). Cell morphology and confluence of vector- or pre-miR-21-infected PA1 cells. Images were photographed on the fourth day of culture using a phase contrast fluorescence microscope (40×) (B). Cell growth WST-1 assays were performed at the indicated time points (one, two, four, six and eight days) and are shown on the X-axis. The Y-axis indicates the absorbance (Abs.) values (Abs. at 450 nm deducted from Abs. at 630 nm background readings). The results shown are from three reproducible experiments (C). * indicates significance at P values less than 0.05. miR, microRNA; OE: overexpression.

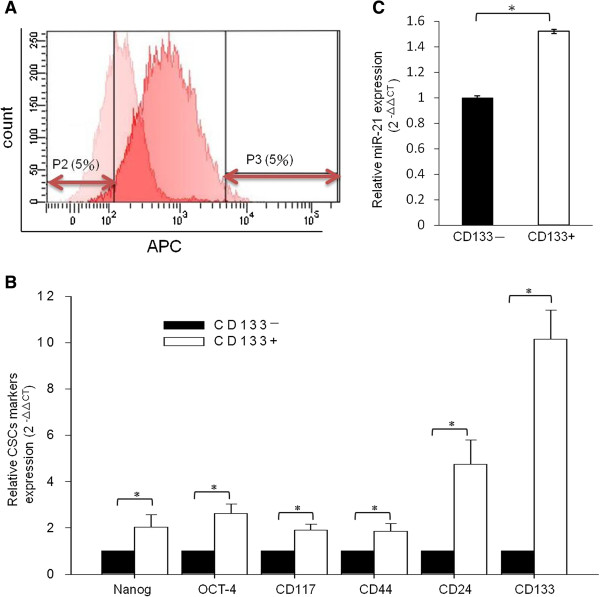

MiR-21 is up-regulated in PA1 CD133+ cells

CD133+ PA1 cells were sorted for further analysis. We gated the 5% extremes of the CD133 staining signal spectrum and defined them as CD133– (P2) and CD133+ (P3) cells (Figure 3A). To confirm that the collected cell population represented CSPCs, CD133 expression levels and other stem cell markers were examined using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (Figure 3B). We found that the expression of CD133 and other stem cell markers was higher in CD133+ cells than in CD133– cells, which suggests that isolated CD133+ cells exhibit CSPC characteristics. We also found that miR-21 levels were higher in CD133+ cells than in CD133– cells (Figure 3C). This finding indicates that miR-21 promotes PA1 cell growth by maintaining CD133+ CSPCs populations.

Figure 3.

MiR-21 was up-regulated in CD133+ PA1 cell populations. APC-conjugated CD133 antibody was used to enrich CSPCs by FACS sorting. The basal IgG-isotype-APC staining signal peaks are presented on the left-hand side and the CD133-APC staining signal peaks are presented on the right-hand side of the histogram. As indicated in P2 and P3, the 5% extremes of the staining signal within the spectrum were sorted. Negatively stained cells (P2, left-hand side 5%) were defined as CD133- and positively stained cells (P3, right-hand side 5%) were defined as CD133+ cells (A). CSPC marker genes were examined using quantitative real-time PCR, and the relative amount of each CSPC marker was calculated as 2-ΔΔCt. The expression of Nanog, OCT-4, CD117, CD44, CD24, and CD133 in CD133– cells was compared with that of each gene in CD133+ cells. (B). MiR-21 expressed in CD133+ and CD133– cells. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to detect expression of miR21. Expression of miR-21 in CD133– cells (basal level) was compared with the level of expression of miR-21 in CD133+ cells (C). The data in (B) and (C) represent the mean of three individual sets of experiments. The variations were from the calculation of standard deviation, and * indicates statistical significance at P-values less than 0.05. APC, allophycocyanin; CSPCs, cancer stem/progenitor cells; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MiR, micro RNA.

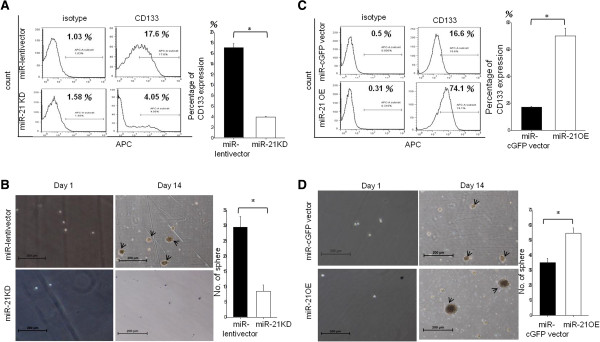

MiR-21 promotes PA1 CSPC self-renewal

Functional assays were performed to confirm the effects of miR-21 on PA1 CSPCs. As seen in Figure 4A, miR-21 knockdown resulted in a marked reduction in CD133 populations compared with vector-infected PA1 cells (Figure 4A). We also found that knockdown of miR-21 resulted in little sphere formation compared with vector-infected controls after 14 days of culture (Figure 4B; black arrows indicate the tumor sphere). On the contrary, overexpression of miR-21 resulted in an increase in CD133 populations (Figure 4C) and CSPC sphere formation (Figure 4D; black arrows indicate the tumor sphere). Taken together, these data indicate that miR-21-related PA1 cell growth is mediated by CSPCs.

Figure 4.

MiR-21 is essential for PA1 CSPCs self-renewal. Flow cytometric signal intensities were used to compare isotype-IgG-APC (left-hand side) and CD133-APC (right-hand side) in PA1 cells. Panel A shows the comparison of CD133+ populations in vector-infected cells (upper panel) and in anti-miR21-infected PA1 cells (lower panel). Sphere formation assay images of the PA1 cell colonies (black arrows indicate the tumor sphere). The sphere colony images were taken under a phase contrast fluorescence microscope (40×). The image on the left-hand side indicates vector-infected cells and the image on the right-hand side indicates anti-miR21-infected PA1 cell sphere colonies (B). Signal intensities of isotype-IgG-APC in PA1 cells (left-hand side) were compared with those of CD133-APC in PA1 cells (right-hand side). CD133+ populations in vector-infected PA1 cells (upper panel) were compared with those in pre-miR21-infected PA1 cells (lower panel) (C). Sphere formation assay images of the PA1 cell colonies (black arrows indicate the tumor sphere). The sphere colony images were taken using a phase contrast fluorescence microscope (40×). The image on the left-hand side indicates vector-infected cell sphere colonies and the image on the right-hand side indicates pre-miR21-infected PA1 cell sphere colonies (D). The scale bar represents 200 μm. APC, allophycocyanin; CSPCs, cancer stem/progenitor cells; IgG, immunoglobulin G; miR, microRNA.

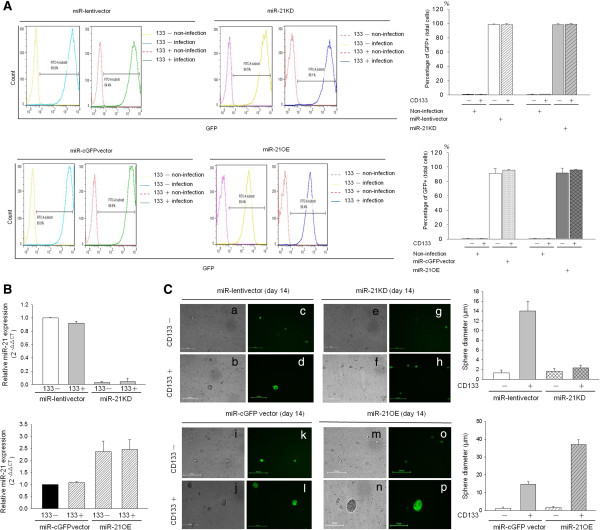

MiR-21 is required for maintaining PA1 CD133+ CSPC

To further prove that miR-21 is essential for CSPC growth and maintenance of its population, we evaluated sphere formation of CD133– and CD133+ cells that had been engineered to either underexpress or overexpress miR-21. CD133+/− cells were sorted using CD133 antibody-coated magnetic beads. The results of flow cytometry revealed that efficient gene transduction occurred in approximately 95% of PA1 cells (Figure 5A). We used qRT-PCR to detect expression of miR-21 in CD133– and CD133+ populations (Figure 5B). As seen in Figure 5B, miR-21 KD: knockdown (upper panel) led to a marked decrease in the expression of miR-21 and miR-21 OE: overexpression (lower panel) resulted in a marked increase in expression of miR-21. In order to test the hypothesis that miR-21 is essential for maintaining the CD133+ pluripotency of OVTC cells, we performed a sphere formation assay. We first used the lentiviral-delivery system to modulate miR-21 (Figure 5A and B) and the results revealed satisfactory infection efficiency. We then sorted CD133−/+ cells for the sphere formation assay (Figure 5C). As shown in Figure 5C, CD133+ cells formed more spheres than CD133– cells in the miR-lentivector- and miR-cGFP vector-infected groups (Figure 5C, left panel). Knockdown or overexpression of miR21 in CD133– cells exerted minor effects on PA1 sphere formation (first and third row), but suppressed (second row) or enhanced (fourth row) PA1 sphere formation in CD133+ cells, respectively. The quantified sphere sizes are shown on the right-hand side of Figure 5C.

Figure 5.

MiR-21 is required for PA1 CD133+ CSPC function. Purified CD133– and CD133+ populations from miR-lentivector, miR-21 KD, miR-cGFPvector and miR-21 OE were collected and the percentage of green fluorescence expression was detected by flow cytometry. The percentage of green fluorescence expression of infected cells was compared with that of non-infected cells. Flow cytometric signal intensities of non-infected cells were compared with those of infected cell populations (left-hand side). The percentages of infected cells with green fluorescence are presented on the right-hand side (A). The relative expression of miR-21 in CD133+ and CD133– cells was detected using quantitative real-time PCR. Expression of miR-21 in CD133– cells (basal level) was compared with that of miR-21 expression in CD133+ cells (B). Sphere formation assay images of the CD133+ and CD133– population colonies. The sphere colony images were taken under a phase contrast fluorescence microscope (100×). The images in the upper panel indicate vector-infected cells (left-hand side) and those on the right-hand side indicate anti-miR21-infected cells. The images of visible light and green fluorescence in the lower panel indicate vector-infected cells (left-hand side) and those on the right-hand side indicate miR21 overexpression (C). The right panel represents quantitation of sphere diameters. Data in (A) and (B) represent the mean of three individual sets of experiments. The variations were from the calculation of standard deviation. The scale bar represents 50 μm. CSPC, cancer stem/progenitor cell; KD: knockdown miR, microRNA; OE.

Taken together, our results indicate that miR-21 is required for the maintenance of pluripotency of OVTC PA1 cells.

Discussion

MiR21 promotes cancer growth and progression

Studies have shown that miRNAs negatively regulate post-transcription in a variety of gene sets and are associated with proliferation, differentiation and progression in various cancers [1-7]. MiR-21 is up-regulated in different kinds of tumors, including breast and ovary [8-16]. Although several studies have indicated that miR-21 expression is high in CSPCs [6-11], the roles that miR-21 plays in CSPCs are still unclear. Herein we have shown that knockdown of miR-21 attenuated PA1 cell growth and that overexpression of miR-21 promoted cell growth.

A number of studies have shown that CD133 is a marker of cancer stem/progenitor cells [30,40,41], and functional assays of CSPCs have revealed that enriched CD133 subpopulations from ovarian cancer tissue are indeed CSPCs [30,40-44]. By manipulating miR-21 levels in the cells, we found that miR-21 is required for maintenance of CD133 populations. Although this finding is consistent with that reported in a previous study [8], it has never been shown in OVTC cells.

Tumor cells with CSPC characteristics grown in suspended conditions with serum-free stem cell culture medium can form tumor spheres [27,29]. The sphere formation assay is widely used to evaluate the self-renewal ability of cancer stem cells in vitro [19,27,28]. In addition to testing the effects of miR-21 on characteristics of cancer progenitor cells, we also examined the self-renewal of CSPCs by conducting a sphere formation assay and found that miR-21 suppresses PA1 cell growth by maintaining CD133+ populations.

Chemotherapy resistance might be associated with miR21-related CSPCs

Chemotherapy resistance and cancer recurrence are major obstacles in the treatment of cancer. Various miRs are associated with cancer cell proliferation and drug resistance [41]. Expression of miR-21, for example, has been demonstrated to be related to chemoresistance in glioma [45], breast [46,47], bladder [48] and neuroblastoma cancer cells [49]. MiR-21 has also been shown to be linked to resistance to at least nine chemotherapy agents, for example, temozolomide [41], trastuzumab [45,46], doxorubicin [47], cisplatin [48], Triptolide [50], and CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, Adriamycin,and prednisone) [51]. Our finding that miR-21 enhances cancer stemness might explain why this small RNA molecule is responsible for resistance to so many chemotherapeutic agents. In our study, knockdown of miR-21 expression suppressed cell growth and tumor cell sphere formation. Moreover, we demonstrated that miR-21 is up-regulated in CD133+ cells (Figure 3C), indicating that it might be important for the maintenance of CSPC populations. CD133+ cells have been reported to be associated with drug resistance in glioblastoma [52], Ewing sarcoma cells [53], lung cancer [54,55] and hepatocellular carcinoma [56]. Our findings indicate that miR-21 plays a critical role in regulating CD133+ CSPCs.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that miR-21 regulates CSPCs populations in PA1 cells. MiR-21, therefore, is a potential target for cancer therapy, especially in patients with cancer relapse.

Abbreviations

BSA: bovine serum albumin; CSPCs: cancer stem/progenitor cells; Ct: threshold value; (D)MEM: (Dulbecco’s) modified Eagle’s medium; EDTA: ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; ELISA: enyme-assisted immunosorbent assay; FACS: fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FBS: fetal bovine serum; FCS: fetal calf serum; GFP: green fluorescent protein; hrbFGF: human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor; hrEGF: human recombinant epidermal growth factor; MACS: magnetic cell separation; miR-21: microRNA-21; OVTC: ovarian teratocarcinoma; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; UTR: untranslated region.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WMC and WCC executed the major experiments and drafted the manuscript. LMC and YYC helped with the design of experiments and manuscript preparation. CRS provided insightful criticism and suggestions on the manuscript. YCH supported and helped with manuscript preparation. WLM supported and supervised the overall project and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

See related commentary by Kang, http://stemcellres.com/content/4/5/110

Contributor Information

Wei-Min Chung, Email: qqrice68@yahoo.com.tw.

Wei-Chun Chang, Email: d1433@mail.cmuh.org.tw.

Lumin Chen, Email: Silvia.Chen@benqmedicalcenter.com.

Ying-Yi Chang, Email: d4754@mail.cmuh.org.tw.

Chih-Rong Shyr, Email: t20608@mail.cmuh.org.tw.

Yao-Ching Hung, Email: ych6375@gmail.com.

Wen-Lung Ma, Email: maverick@mail.cmu.edu.tw.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Dr. Min-Chie Hung’s and Yuh-Pyng Sher’s generosity for providing cell lines. Thanks also to Jeffrey Conrad for helping with language improvement. We thank Dr. Chawnshang Chang for his advice on this study. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Council (NSC101-2314-B-039-027-MY3 to L Chen and YC Hung; NSC101-2314-B-039-014 to YY Chang and YC Hung; NSC100-2314-B-039-001-MY2 to WL Ma), and by a grant from the China Medical University Hospital (CMR-101-070 to WC Chang, and WL Ma).

References

- Garg M. MicroRNAs, stem cells and cancer stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2012;4:62–70. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v4.i7.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Control of protein synthesis and mRNA degradation by microRNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekulaeva M, Filipowicz W. Mechanisms of miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation in animal cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuklu SD, Donoghue MT, Spillane C. miR-21 as a key regulator of oncogenic processes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:918–925. doi: 10.1042/BST0370918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Wang Y, Liu M, Bi X, Bao J, Zeng N, Zhu Z, Mo Z, Wu C, Chen X. MiR-21 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression in third-sphere forming breast cancer stem cell-like cells. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1058–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Kagalwala MN, Parker-Thornburg J, Adams H, Majumder S. REST maintains self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2008;453:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature06863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSano JT, Xu L. MicroRNA regulation of cancer stem cells and therapeutic implications. AAPS J. 2009;11:682–692. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangaraju VK, Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:116–125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask L, Balslev E, Jorgensen S, Eriksen J, Flyger H, Moller S, Hogdall E, Litman T, Nielsen BS. High expression of miR-21 in tumor stroma correlates with increased cancer cell proliferation in human breast cancer. APMIS. 2011;119:663–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LX, Wu QN, Zhang Y, Li YY, Liao DZ, Hou JH, Fu J, Zeng MS, Yun JP, Wu QL, Zeng YX, Shao JY. Knockdown of miR-21 in human breast cancer cell lines inhibits proliferation, in vitro migration and in vivo tumor growth. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R2. doi: 10.1186/bcr2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Wang C, Liu J, Wang X, Lv L, Wei L, Xie L, Zheng Y, Song X. MicroRNA-21 regulates breast cancer invasion partly by targeting tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 expression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:29. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Cui Z, Wang F, Yang X, Qian J. miR-21 down-regulation promotes apoptosis and inhibits invasion and migration abilities of OVCAR3 cells. Clin Invest Med. 2011;34:E281. doi: 10.25011/cim.v34i5.15671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Yang X, Wang F, Cui Z, Huang Y. MicroRNA-21 promotes the cell proliferation, invasion and migration abilities in ovarian epithelial carcinomas through inhibiting the expression of PTEN protein. Int J Mol Med. 2010;26:819–827. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Liu M, Wang Y, Mo Z, Bi X, Liu Z, Fan Y, Chen X, Wu C. Re-expression of miR-21 contributes to migration and invasion by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition consistent with cancer stem cell characteristics in MCF-7 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;363:427–436. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Liu M, Wang Y, Chen X, Xu J, Sun Y, Zhao L, Qu H, Fan Y, Wu C. Antagonism of miR-21 reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell phenotype through AKT/ERK1/2 inactivation by targeting PTEN. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Balch C, Chan MW, Lai HC, Matei D, Schilder JM, Yan PS, Huang TH, Nephew KP. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4311–4320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasim T, Majrroh A, Siddiq S. Comparison of clinical presentation of benign and malignant ovarian tumours. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira FG, Dozortsev D, Diamond MP, Fracasso A, Abdelmassih S, Abdelmassih V, Goncalves SP, Abdelmassih R, Nagy ZP. Evidence of parthenogenetic origin of ovarian teratoma: case report. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1867–1870. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye LY, Wang JJ, Liu DR, Ding GP, Cao LP. Management of giant ovarian teratoma: a case series and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:672–676. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviracevic B, Sedlar S, Malobabic D, Cuk D. [Mixed malignant germ cell tumor of ovary] Med Pregl. 2011;64:93–95. doi: 10.2298/MPNS1102093S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moniaga NC, Randall LM. Malignant mixed ovarian germ cell tumor with embryonal component. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshy M, Vijayananthan A, Vadiveloo V. Malignant ovarian mixed germ cell tumour: a rare combination. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2005;1:e10. doi: 10.2349/biij.1.2.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Datar R, Cote R. Technologies and methods used for the detection, enrichment and characterization of cancer stem cells. Natl Med J India. 2010;23:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, Dombkowski D, Preffer F, Maclaughlin DT, Donahoe PK. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11154–11159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapat SA, Mali AM, Koppikar CB, Kurrey NK. Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3025–3029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Convery PA, Matsumura N, Whitaker RS, Kondoh E, Perry T, Huang Z, Bentley RC, Mori S, Fujii S, Marks JR, Berchuck A, Murphy SK. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133+ ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:209–218. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Zeng J, Liang B, Zhao Z, Sun L, Cao D, Yang J, Shen K. Ovarian cancer cells with the CD117 phenotype are highly tumorigenic and are related to chemotherapy outcome. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao MQ, Choi YP, Kang S, Youn JH, Cho NH. CD24+ cells from hierarchically organized ovarian cancer are enriched in cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:2672–2680. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysar SB, Jimeno A. More than markers: biological significance of cancer stem cell-defining molecules. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2450–2457. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong MY, Kakar SS. The role of cancer stem cells and the side population in epithelial ovarian cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:113–120. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darido C, Georgy SR, Wilanowski T, Dworkin S, Auden A, Zhao Q, Rank G, Srivastava S, Finlay MJ, Papenfuss AT, Pandolfi PP, Pearson RB, Jane SM. Targeting of the tumor suppressor GRHL3 by a miR-21-dependent proto-oncogenic network results in PTEN loss and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeri N, Gasparini P, Braconi C, Paone A, Lovat F, Fabbri M, Sumani KM, Alder H, Amadori D, Patel T, Nuovo GJ, Fishel R, Croce CM. MicroRNA-21 induces resistance to 5-fluorouracil by down-regulating human DNA MutS homolog 2 (hMSH2) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21098–21103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015541107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma WL, Hsu CL, Yeh CC, Wu MH, Huang CK, Jeng LB, Hung YC, Lin TY, Yeh S, Chang C. Hepatic androgen receptor suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through modulation of cell migration and anoikis. Hepatology. 2012;56:176–185. doi: 10.1002/hep.25644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SO, Ma Z, Yeh CR, Luo J, Lin TH, Lai KP, Yamashita S, Liang L, Tian J, Li L, Jiang Q, Huang CK, Niu Y, Yeh S, Chang C. New therapy targeting differential androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer stem/progenitor vs. non-stem/progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;5:14–26. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson KM, Boente MP, Pambuccian SE, Skubitz AP. Disaggregation and invasion of ovarian carcinoma ascites spheroids. J Transl Med. 2006;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R, Wu Q, Liu F, Wang Y. Description of the CD133+ subpopulation of the human ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR3. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryczek I, Liu S, Roh M, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Wei S, Banerjee M, Mao Y, Kotarski J, Wicha MS, Liu R, Zou W. Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase and CD133 defines ovarian cancer stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:29–39. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam EJ, Lee M, Yim GW, Kim JH, Kim S, Kim SW, Kim YT. MicroRNA profiling of a CD133(+) spheroid-forming subpopulation of the OVCAR3 human ovarian cancer cell line. BMC Med Genomics. 2012;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley MD, Therrien VA, Cummings CL, Sergent PA, Koulouris CR, Friel AM, Roberts DJ, Seiden MV, Scadden DT, Rueda BR, Foster R. CD133 expression defines a tumor initiating cell population in primary human ovarian cancer. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2875–2883. doi: 10.1002/stem.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Terauchi M, Umezu T, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Nawa A, Kikkawa F. Identification and characterization of cancer stem cells in ovarian yolk sac tumors. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2179–2185. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ST, Zhang XQ, Zhuang JT, Chan HL, Li CH, Leung GK. MicroRNA-21 inhibition enhances in vitro chemosensitivity of temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2835–2841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C, Yao Y, Wang Y, Liu B, Wu W, Chen J, Su F, Yao H, Song E. Up-regulation of miR-21 mediates resistance to trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19127–19137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZX, Lu BB, Wang H, Cheng ZX, Yin YM. MicroRNA-21 modulates chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells to doxorubicin by targeting PTEN. Arch Med Res. 2011;42:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Lu Q, Wu D, Li P, Xu B, Qing W, Wang M, Zhang Z, Zhang W. microRNA-21 modulates cell proliferation and sensitivity to doxorubicin in bladder cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1721–1729. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tsai YH, Fang Y, Tseng SH. Micro-RNA-21 regulates the sensitivity to cisplatin in human neuroblastoma cells. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1797–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Hui L, Xu W, Shen H, Chen Q, Long L, Zhu X. Triptolide modulates the sensitivity of K562/A02 cells to adriamycin by regulating miR-21 expression. Pharm Biol. 2012;50:1233–1240. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2012.665931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H, Wei J, Deng C, Yang X, Wang C, Xu R. MicroRNA-21 regulates the sensitivity of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells to the CHOP chemotherapy regimen. Int J Hematol. 2012;97:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, Tunici P, Ng H, Abdulkadir IR, Lu L, Irvin D, Black KL, Yu JS. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Gwye Y, Russell D, Cao C, Douglas D, Hung L, Kovar H, Triche TJ, Lawlor ER. CD133 expression in chemo-resistant Ewing sarcoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini G, Roz L, Perego P, Tortoreto M, Fontanella E, Gatti L, Pratesi G, Fabbri A, Andriani F, Tinelli S, Roz E, Caserini R, Lo Vullo S, Camerini T, Mariani L, Delia D, Calabro E, Pastorino U, Sozzi G. Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16281–16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905653106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Yang CJ, Huang MS, Yeh CT, Wu AT, Lee YC, Lai TC, Lee CH, Hsiao YW, Lu J, Shen CN, Lu PJ, Hsiao M. Cisplatin selects for multidrug-resistant CD133+ cells in lung adenocarcinoma by activating Notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2013;73:406–416. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodzin AS, Wei Z, Hurtt R, Gu T, Doria C. Gefitinib resistance in HCC mahlavu cells: upregulation of CD133 expression, activation of IGF-1R signaling pathway, and enhancement of IGF-1R nuclear translocation. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2947–2952. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]