A Nordic Welfare Model?

The Nordic countries are all established welfare states, and there has for some time existed a notion of a distinctive Nordic or Scandinavian welfare state; it is often understood in terms of broad, tax-financed public responsibility and legislated, collective, and universalistic solutions that respect employment interest yet aim at welfare and equity goals (1). Lately, the Nordic countries have performed well in comparative research of health policy in European countries (2) but also regarding health care system in OECD countries (3). However, while it appears that the case for the existence of a Nordic model is strong there is actually no consensus of the precise specification of the feature that defines the model (1). For example, considerable differences seem to exist between the psychiatric services within, as well as between, the Nordic countries when it comes to history, mental health acts and allocation of resources (4). Furthermore, some scholars argue that it is not even possible to speak of a common Nordic political approach to public health, since the public health programs in the different Nordic countries contain contradictory policies and ideological statements (5). This is especially evident for depression and sales of antidepressants in the different Nordic countries.

Depression in the Nordic Countries

Depression is now regarded by the World Health Organization to be one of the most burdensome diseases in the world and deemed a public health priority (6). Overall, depression is estimated to have a point prevalence of about 5% in a general population, and a lifetime risk of about 15% (7). The prevalence of depression in the Nordic countries is believed to vary between 3.5 and 5% (8–12). However, information on depression prevalence in the different Nordic countries is quite difficult to find and the Nordic Governmental Websites does not seem to be up-to-date. For example, according to the Danish Centre for Health Technology Assessment (DACEHTA), the prevalence of depression in Denmark is not especially well investigated (13) and often relies on earlier research suggesting a point prevalence of 3% of the Danish population or 150 000 individuals (13, 14). More recent research has suggested that the prevalence of major depression disorder (MDD) in Denmark 2000–2006 increased from 2.0 to 4.9% and is now suggested to be of public health importance (10). The public health concerns is also raised in Finland and according to the Finnish Health 2000 project over 5% of the Finnish population seem to suffer from depression (9). Iceland is for some reason often not included in Nordic or European comparative studies and information on the prevalence of depression in Iceland seems to be scarce (15). According to information on their Website 15–25% of all Icelanders can expect to be depressed sometimes in their life and 12 000–15 000 individuals are predicted to suffer from depression at any given moment (10). This is equal to 3.8–4.8% of the Icelandic population. In Sweden, information provided by the Medical Products Agency suggests that approximately 5% of the Swedish population is afflicted by depression (12). In Norway, according to the classic Norwegian psychiatric epidemiological HUNT studies, depression affects approximately 3.5% of the Norwegian population (11).

Use of Antidepressants

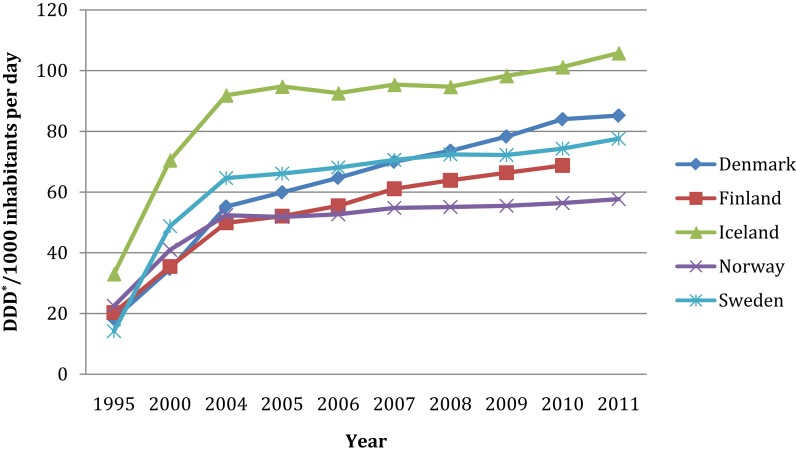

The most common form of treatment of depression is antidepressant medication. They are currently ranked ninth among prescription drugs with global sales well over $20 billion (16). Overall, antidepressant prescriptions have risen, but this has been offset by a number of patent expiries and generic alternatives (17). As Figure 1 shows, sales of antidepressants in the Nordic countries have increased up to fourfold since the middle of the 90s (18, 19).

Figure 1.

Sales of antidepressants (N06A) in the Nordic Countries during 1995–2011 in DDD*/1000 inhabitants per day. *Defined Daily Doses according to WHO classification.

The overall sales of antidepressant drugs in the Nordic countries in 2009 (74.1 DDD/1000 inhabitants per day) is considerable higher than the OECD average (52.5), but also higher than for example in the UK (60.9) (20). However, there are great variations between the countries, where Iceland by far has the highest level of antidepressant sales, almost double that in Norway. In total, approximately 2 million Nordic inhabitants were prescribed an antidepressant, almost a share of 8.5% at a total cost of €236 million according to latest available statistics (ranging from 2010 to 2012). Danish medical statistics shows that there were sales of antidepressants in 2011 of €68 million and over 460 000 Danes were prescribed an antidepressant (8.3% of the population) (21). According to the Finnish Medicines Agency Fimea and Social Insurance Institution in 2010, estimated sales for antidepressants in Finland reached well over €44 million and more than 430 000 Finns were prescribed an antidepressant in 2010 (8.3% of the total Finnish population) (22). As reported by the Icelandic Medicines Agency estimated sales for antidepressants in 2010 were approximately €4 million (23), and over 35 000 patients in Iceland were prescribed an antidepressant in 2011 (11.2% of the total population) (24). Almost 300 000 Norwegians were prescribed an antidepressant in 2011 (6.3% of the population) and estimated sales were almost €50 million (25). In 2010, approximately 8.1% of the Swedish population did purchase an antidepressant drug and more than 5 million prescriptions of antidepressants were dispensed to almost 760 000 patients (26); antidepressant sales were estimated to almost €70 million (27).

How Can This Rise in Antidepressants be Explained?

Several factors such as accessibility of drugs, available treatment alternatives, clinical practice and national guidelines, may influence patterns of prescribing and use of antidepressant drugs in the Nordic countries. Iceland has had a remarkable increase in antidepressant sales since 1995 (as indicated in Figure 1). An Icelandic study examining public views on antidepressant treatment suggested that the reason for the high usage of antidepressant in Iceland was a result of their perceived effectiveness by users, but also an effect of limited access to alternative treatment like psychotherapy (28). On the other hand, additional Icelandic research has suggested that despite an increase in antidepressants there were no positive impact on public health; instead the rates of psychiatric outpatient consultation and in patient treatment for depressive disorder increased, leading to increased medical costs (29). In a public health perspective this medical approach may seems questionable, but without further research on depression prevalence and why antidepressants are prescribed it is difficult to assess potential public health effects. This is of particular concern, since antidepressants in the absence of therapeutics alternatives are projected to continue to dominate the antidepressant market to 2018 (17).

Further research is therefore needed to scrutinize as to why differences in prevalence of depression and antidepressant sales exist between the Nordic countries, despite the Nordic model. The Nordic countries do for some reason have a high consumption of antidepressants compared to OECD despite relatively moderate or low depression prevalence patterns. This is especially important, since the increase in antidepressants consumption has spurred an ongoing debate whether antidepressants are overprescribed (30) (medicalization) or underprescribed (31) (poor access to treatment). With the increasing burden of disease due to mental disorders worldwide, knowledge of the epidemiology of these disorders are of increasing interest, and as indicated by others scholars (32) the Nordic countries have a strong history in this field of research. Otherwise valuable Nordic public health research may never be performed, despite its merits and its potential.

Funding

This study has received funding from Letterstedska föreningen and Lundgrenska Fonden. The sponsor had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The researcher was independent of the funders.

References

- 1.Kautto M. The Nordic countries. In: Castles FG, Leibfried S, Lewis J, Obinger H, Pierson C. editors. The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (2010). p. 586–615 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenbach JP, McKee M. A comparative analysis of health policy performance in 43 European countries. Eur J Public Health (2013) 23(2):195–201 10.1093/eurpub/cks192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tchouaket ÉN, Lamarche PA, Goulet L, Contandriopoulos AP. Health care system performance of 27 OECD countries. Int J Health Plann Manage (2012) 27:104–29 10.1002/hpm.1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson L. In what ways do characteristics of psychiatric services determine contact rates and use of services? The Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (1997) 32:3–4 10.1007/BF00800660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallgårda S. Addressing individual behaviours and living conditions: four Nordic public health policies. Scand J Public Health (2011) 39(Suppl 6):6–10 10.1177/1403494810378922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice: A Summary Report/A Report from the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth). Geneva: World Health Organization; (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lönnqvist J. Major psychiatric disorders in suicide and suicide attempters. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C. editors. Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention: A Global Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (2009). p. 275–86 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen I, Thielen K, Bech P, Nygaard E, Diderichsen F. Increasing prevalence of depression from 2000 to 2006. Scand J Public Health (2011) 39(8):857–63 10.1177/1403494811424611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aromaa A, Koskinen S. Health and Functional Capacity in Finland. Helsinki: KTL National Public Health Institute; (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Directorate of Health Health and Well-Being [in Icelandic] (2012) [accessed 2012 Nov 9]. Available from: www.landlaeknir.is/heilsa-og-lidan/verkfni/item16380/Thjod_gegn_thunglyndi

- 11.Hildrum B, Romild U, Holmen J. Anxiety and depression lowers blood pressure: 22 year follow-up of the population based HUNT study, Norway. BMC Public Health (2011) 11:601. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MPA Läkemedelsbehandling av depression hos vuxna och äldre [in Swedish] (2007) [accessed 2012 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/malgrupp/Allmanhet/Att-anvandalakemedel/Sjukdom-och-behandlingsrekommendationer---listan/Depression-hos-vuxnaoch-aldre/

- 13.Eplov LF, Jörgensen T, Hougaard E, Kessing L, Larsen L, Stage K, et al. Behandling af depressionssygdomme. Kommentering af: Behandling af depressionssjukdomar. En systematisk litteraturöversikt, Volym 1–3. Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering. [in Danish]. Copenhagen: Danish Health and Medicines Authority, Danish Centre for Health Technology Assessment (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P. Prevalence of major depression and stress indicators in the Danish general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2004) 109:96–103 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigbjörnsdóttir HB. Icelandic Directorate of Health. Personal communication (2013).

- 16.IMS Health Top 20 Global Therapeutic Classes, 2010, Total Audited Markets (2010) [accessed 2012 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/ims/Global/Content/Corporate/Press%20Rom/Top-line%20Market%20Data/Top_20_Global_Therapy_Classes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.GBI Research Antidepressant Market to 2018 – Despite Safety Concerns, Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Continue to Dominate in the Absence of Effective Therapeutic Alternatives. (2012) [accessed 2012 Nov 18]. Available from: www.gbiresearch.com/Report.aspx?ID=Antidepressants-Market-to-2018-DespiteSafety-Concerns-Selective-Serotonin-Re-uptake-Inhibitors-(SSRIs)-Continue-toDominate-in-the-Absence-of-Effective-Therapeutic-Alternatives

- 18.NOMESCO Medicines Consumption in the Nordic Countries 1999–2003. Copenhagen: Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee; (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 19.NOMESCO Medicines Consumption in the Nordic Countries 2004–2008. Copenhagen: Nordic Medico Statistical Committee; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.OECD Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; (2011). 10.1787/health_glance-2011-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statens Serum Institut (2012) [accessed 2012 Nov 8]. Available from: www.medstat.dk

- 22.Finnish Medicines Agency Fimea and Social Insurance Institution Finnish Statistics on Medicines. Helsinki: Finnish Medicines Agency Fimea and Social Insurance Institution; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Icelandic Medicine Agency Lyfjastofnun – Icelandic Medicines Agency. (2012) [accessed 2012 Nov 8]. Available from: www.imca.is/imca/statistics/

- 24.Arnórsson M. Head of Information. Icelandic Medicines Agency. Personal communication (2008).

- 25.Berg C, Furu K, Mahic M, Litleskare I, Rönning M, Sakshaug S, et al. The Norwegian Prescription Database 2006–2010. Oslo: The Norwegian Institute of Public Health; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 26.The National Board of Health and Welfare Official Statistics of Sweden. Statistics Health and Medical Care. Pharmaceutical-Statistics for 2010. Stockholm: The National Board of Health and Welfare; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 27.The National Board of Health and Welfare Official Statistics of Sweden. Statistics Health and Medical Care. Pharmaceuticals-Statistics for 2009. Stockholm: The National Board of Health and Welfare; (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigurdsson E, Ólafsdóttir T, Gottfredsson M. Public views on antidepressant treatment: lessons from a national survey. Nord J Psychiatry (2008) 62:374–8 10.1080/08039480801984156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helgason T, Tómasson H, Zoëga T. Antidepressants and public health in Iceland. Time series analysis of national data. Br J Psychiatry (2004) 184:157–62 10.1192/bjp.184.2.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spence D. Are antidepressants overprescribed? Yes. BMJ (2013) 346:f191. 10.1136/bmj.f191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid IC. Are antidepressants overprescribed? No. BMJ (2013) 346:f190. 10.1136/bmj.f190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allebeck P. The use of population based registers in psychiatric research. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2009) 120:386–91 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]