In 1983 the countries of the Americas, with the technical cooperation of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), pledged to eliminate human rabies transmitted by dogs.1 Since then, countries have made great efforts to eliminate this disease, with notable success, within the framework of the Regional Program of Elimination of Human Rabies. The success achieved during the last 30 years and the historical solidarity between countries in the region support the goal of elimination of dog-transmitted rabies in the American continent by 2015. As this date approaches, there is a need to reflect and reassess the current plan of rabies elimination. This work briefly describes the achievements of the Regional Program and the proposed new Regional Action Plan for the elimination of dog-transmitted rabies.

The technical support for the Regional Program for Elimination of Human Rabies is founded on the resolutions of the Meeting of Directors of the National Rabies Control Program in the Americas (Reunión de Directores de los Programas Nacionales de Control de Rabia en América Latina-REDIPRA). Approximately every 2 years, PAHO convenes the REDIPRA, during which the countries present and discuss the epidemiological situation with regard to rabies and strategies for prevention. The conclusions and recommendations of the REDIPRA are submitted for consideration and approval by the Ministers of Health and Agriculture of PAHO member states during the Inter-American Meeting at the Ministerial Level of Health and Agriculture (Reunión Interamericana a Nivel Ministerial en Salud y Agricultura-RIMSA). Inter-sectorial policies relating to the rabies elimination program are discussed within the RIMSA to be submitted later to the PAHO Directive Council.

There have been strong political mandates and international commitments for the elimination of human rabies transmitted by dogs in the Americas since 1983.2 In 2009, the PAHO Directive Council, by resolution CD 49.R19,3 called the countries of the Americas to commit to the elimination or reduction of neglected diseases and other poverty-related diseases including the elimination of dog-transmitted rabies by 2015.4

Since the implementation of the Regional Program, the number of human cases has decreased by ∼95% (from 355 cases in 1982 to 10 cases in 2012).5 In dogs, the reduction has been of 98% (from 25,000 cases in 1980 to fewer than 400 in 2010).5 Much of this success has been a result of the application of dog vaccine and the strong cooperation between health and agriculture sectors of member countries, and the collaboration of regional agencies, international, public, private, and non-governmental organizations.6 The Regional Rabies Program has been considered since its inception as an intersectoral initiative within the framework of One Health, where epidemiological surveillance includes cases in humans, domestic animals, animals of economic interest, and wildlife.

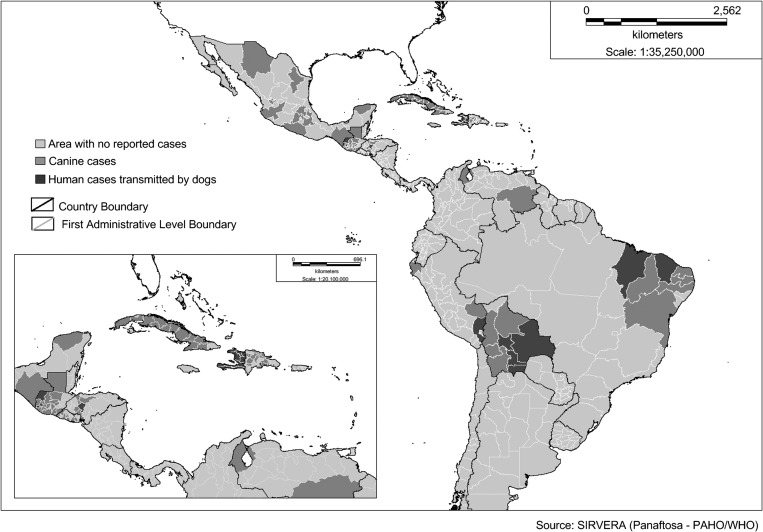

Today, most parts of the Americas have already eliminated the circulation of rabies virus in canine populations.7,8 Cases of human rabies transmitted by dogs in the region are circumscribed to a small number of well-defined areas9 (Figure 1). Of the 570 first administrative level sub-units (province, state, or department) in Latin America, only 11 units (2%) reported cases of human rabies transmitted by dogs in the last 4 years. These cases are concentrated in areas of the periphery of big cities, neglected communities, or international border areas where the population has little information about the risks of the disease, limited access to quality health services and poor living standards or working conditions. These areas are also characterized by having a high proportion of unvaccinated dogs10 and of limited availability or accessibility to immunobiological products for pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis.11,12

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of the occurrence of human and canine rabies antigenic variant 1 and 2, during the period from 2009 to 2012 in the Americas.

The elimination of these pockets of disease depends on the local implementation of proven control plans, widespread participation of the population, and the technical cooperation between countries.

As commonly seen in control efforts for other diseases, the reduction of the number of cases of human rabies transmitted by dogs has led to a parallel decline in the attention given to the disease by institutions and health departments. Even for endemic areas within countries, the competitive allocation of scarce funds to other priorities at the national level can result in the allocation of fewer resources for the fight against rabies at lower administrative levels. As a result, institutional memory and awareness among the population might be lost.

PAHO has prioritized technical cooperation for the implementation of the Regional Program on four pillars of action: attention to populations at risk, canine rabies vaccination, surveillance, and training and communication. Care for people at risk of infection is based on ensuring universal access to pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis and decentralization of health care to secure access. The effective distribution of post-exposure prophylaxis to all people exposed to rabies is a logistical challenge, especially given the marginalization of populations currently affected. Canine rabies vaccination has been used successfully as a cost effective approach with over 40 million dogs vaccinated every year in the Americas. However, enzootic areas fail to maintain vaccination levels needed to interrupt transmission of rabies among dogs.

PAHO has developed an Action Plan for 2014–2018. The proposed plan is founded on the belief that political and organizational constraints are the most limiting factors for the elimination of rabies in most of the areas in the region where cases still occur. On this basis, the plan emphasizes robust managerial and evaluation processes to support systematization of activities leading to increased accountability. The plan also recognizes that some countries may still face technical limitations and seeks the regional collaboration between countries to mitigate these differences. On this note, the plan acknowledges the relevance of collaboration between the countries in South America and aims to align itself with other regional initiatives.

The action plan proposes the creation of sustainable mechanisms based on the participation of all community levels with a strong cross-cutting component. This plan will promote the following goals:

Goal 1: Ensure timely access, availability, and quality of immunobiologicals to people exposed to rabies virus.

Goal 2: Keep appropriate levels of vaccination coverage in dogs in high enzootic areas.

Goal 3: Strengthen rabies national plans and ensure their systematic implementation.

Goal 4: Strengthen the REDIPRA network to ensure the participation and collaboration between countries.

Goal 5: Strengthen the surveillance system of human rabies transmitted by dogs.

Goal 6: Implement an Inter-American Network of Diagnostic Laboratories (REDILAR) to facilitate rapid diagnosis, training, and the development of a laboratory quality control system, particularly in high enzootic areas.

Goal 7: Strengthen the education, communication, and advocacy in enzootic areas to ensure the necessary and continuous political support.

Goal 8: Develop and adoption of a guide that delineate the requirements for declaring countries or areas free of dog-transmitted rabies. Therefore, it will be required that rabies would be declared a notifiable disease.

The progress of the implementation of the plan needs to be constantly monitored and evaluated at national and regional level, identifying areas for improvement and optimization of the use of financial and human resources. To be successful, it is important that affected countries adapt the plan to the reality of each country to respond appropriately and establish integrated strategies for rabies prevention. Countries should commit to strengthen their epidemiological surveillance and laboratory diagnosis, as well as their national health systems, placing more emphasis on populations and vulnerable groups like those in remote areas and outskirts of large cities. However most important, countries should ensure the action plan becomes effective at the local level, taking into account the processes of decentralization of health services and mobilizing resources to achieve a sustainable national program for the elimination of rabies.

The implementation of many of the activities suggested by the plan, as they target universally applicable traits such as accountability and improved communication, should benefit efforts against other diseases, most prominently other zoonoses. This is in recognition that rabies persistence is not an isolated problem within the endemic areas, but a simple manifestation of serious limitations affecting the delivery of even basic health functions.

PAHO has the mandate of supporting the coordination and implementation of the action plan at the national, sub-regional, and regional level and advocate for active mobilization of resources and cooperation to promote partnerships, collaboration, and networking. The greatest challenge will be to motivate governments to maintain the political, technical, and budgetary commitment to meet the goal of elimination, keeping rabies in their political agenda.

The action plan for the elimination of dog-transmitted rabies was presented to the REDIPRA XIV meeting in Lima, Peru in the summer of 2013. The agenda of the meeting focused on the creation of the working groups to ensure regular follow-up of the plan. In addition, the meeting agreed on the planned timeline of activities to reach the goal of elimination of dog-transmitted rabies in the region. Working groups constituted by the representatives of the countries, on sponsorship, technical cooperation, and advocacy, will progress to further the objectives of the plan with specific agendas. The PAHO will provide secretariat support to the REDIPRA. Virtual meetings and regular communications will be pursued within and between the working groups to monitor progress. We want to emphasize the importance of the political commitment in the final stage of this process. The availability of strategies for rabies control demonstrated successfully for decades, the experience of most countries in the region, and the historical ties of solidarity between countries with the support of the scientific community are evidence to affirm that the elimination of dog-transmitted rabies can be achieved in the short term. The final effort to confront the obstacles already identified and secure the free status of many countries in the Americas is the key for eliminating human rabies transmitted by dogs.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Alfonso Clavijo, Victor Javier Del Rio Vilas, and Friederike Luise Mayen, Pan American Health Organization, Veterinary Public Health Unit, Health Surveillance and Disease Prevention and Control, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, E-mails: aclavijo@paho.org, vdelrio@paho.org, and mayenf@paho.org. Zaida Estela Yadon, Pan American Health Organization, Health Surveillance and Disease Prevention, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, E-mail: yadonzai@panaftosa.ops-oms.org. Albino Jose Beloto, Consultant, Veterinary Public Health, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, E-mail: albino.belotto@gmail.com. Marco Antonio Natal Vigilato, Pan American Health Organization, Veterinary Public Health, Lima, Peru, E-mail: vigilato@paho.org. Maria Cristina Schneider, Pan American Health Organization, International Health Regulations, Washington, DC, E-mail: schneidc@paho.org. Ottorino Cosivi, Pan American Health Organization, Veterinary Public Health, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, E-mail: cosivio@panaftosa.ops-oms.org.

References

- 1.Organización Panamericana de la Salud . Eliminación de la Rabia Humana Transmitida por Perros en América Latina. Washington, DC: 2005. http://bvs1.panaftosa.org.br/cgi-bin/wxis1660.exe/lildbi/iah/ Available at. Accessed February 10, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS) I- XIII Reunión de Directores de los Programas Nacionales de Control de la Rabia en América Latina. 2013. http://bvs1.panaftosa.org.br/local/File/textoc/ Available at. Accessed March 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organización Panamericana de la Salud . Resolución CD49.R19: Eliminación de las Enfermedades Desatendidas y otras Infecciones Relacionadas con la Pobreza. En: 49.o Consejo Directivo, 61.a Sesión del Comité Regional de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) para las Américas. 2009. http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/CD49.R19%20(Esp.).pdf Available at. Accessed February 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . Sustaining the Drive to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Second WHO Report on Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/resources/en/index.html Available at. Accessed March 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS) Sistema de Información Regional para a Vigilancia Epidemiológica de Rabia (SIRVERA) 2013. http://sirvera.panaftosa.org.br/AcessoLivre/Logon.aspx?ReturnUrl=%2fAcessoGeral%2fDefault.aspx Available at. Accessed February 10, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider MC, Belotto A, Adé MP, Hendrickx S, Leanes LF, Rodrigues MJ, Medina G, Correa E. Current status of human rabies transmitted by dogs in Latin America. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;23:2049–2063. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007000900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belotto A, Leanes LF, Schneider MC, Tamayo H, Correa E. Overview of rabies in the Americas. Virus Res. 2005;111:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rupprecht CE, Barrett J, Briggs D, Cliquet F, Fooks AR, Lumlertdacha B, Meslin FX, Müler T, Nel LH, Schneider C, Tordo N, Wandeler AI. Can rabies be eradicated? Dev Biol (Basel) 2008;131:95–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider MC, Aguilera XP, Barbosa da Silva Junior J, Ault SK, Najera P, Martinez J, Requejo R, Nicholls RS, Yadon Z, Silva JC, Leanes LF, Periago MR. Elimination of neglected diseases in Latin America and the Caribbean: a mapping of selected diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fooks AR. Rabies remains a “neglected disease”. Euro Surveill. 2005;10:211–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz M, Chávez CB. Rabies in Latin America. Neurol Res. 2010;32:272–277. doi: 10.1179/016164110X12645013284257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benitez JA, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Vivas P, Plaz J. Burden of zoonotic diseases in Venezuela during 2004 and 2005. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1149:315–317. doi: 10.1196/annals.1428.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]