Abstract

We report cloning, expression, purification, and characterization of three predicted leptospiral membrane proteins (LIC11360, LIC11009, and LIC11975). In silico analysis and proteinase K accessibility data suggest that these proteins might be surface exposed. We show that proteins encoded by LIC11360, LIC11009 and LIC11975 genes interact with laminin in a dose-dependent and saturable manner. The proteins are referred to as leptospiral surface adhesions 23, 26, and 36 (Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36), respectively. These proteins also bind plasminogen and generate active plasmin. Attachment of Lsa23 and Lsa36 to fibronectin occurs through the involvement of the 30-kDa and 70-kDa heparin-binding domains of the ligand. Dose-dependent, specific-binding of Lsa23 to the complement regulator C4BP and to a lesser extent, to factor H, suggests that this protein may interfere with the complement cascade pathways. Leptospira spp. may use these interactions as possible mechanisms during the establishment of infection.

Introduction

Leptospirosis is an acute febrile disease caused by pathogenic spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. The disease is considered, according to the World Health Organization, as an important emerging infectious disease that affects populations worldwide. In tropical and subtropical regions, the disease is considered endemic, whereas in temperate climate, the disease is more associated with occupational and recreational activities.1 Structural heterogeneity in the carbohydrate component of leptospiral lipopolysaccharides results in serovar diversity; more than 250 serovars have been described.2 Many serovars are adapted for specific mammalian reservoir hosts, which harbor the organisms in their renal tubules and shed live leptospires in their urine. Humans are accidental hosts who become infected through contact with wild or domestic animals or exposure to contaminated soil or water.3

Our laboratory has been using bioinformatics software, such as PSORT4 and LipoP,5 to analyze genome sequences of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni.6,7 This approach, combined with gene cloning and protein expression and purification, has led to development of several leptospiral recombinant proteins that can be experimentally characterized. Some of these proteins were identified as novel leptospiral adhesins that might be involved in the first steps of host-Leptospira interaction.8–18 After attachment, leptospires have to overcome tissue barriers and reach target organs. Proteolytic activity by plasmin (PLA) generation at the surface of Leptospira spp. via binding of host plasminogen (PLG) in the presence of an activator has been described.19 Furthermore, our group has identified several leptospiral proteins as PLG-binding receptors.8,15–18,20 Recently, we have reported two leptospiral proteins capable of binding the complement regulator C4BP, an interaction that might help the bacteria evade the immune system and increase survival.17,18

In the present study, we report the characterization of three novel leptospiral proteins. The selected genes, LIC11009, LIC11360, and LIC11975, were identified in genome sequences of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni6,7 and predicted to encode for membrane proteins. We show that the recombinant proteins bind extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules and are referred to as leptospiral surface adhesions Lsa23 (rLIC11360), Lsa26 (rLIC11009), and Lsa36 (rLIC11975) (number indicates molecular mass of the protein). These proteins are capable of binding PLG and generating enzymatically active PLA. Moreover, Lsa23 interacts with C4BP and factor H complement regulators. These recombinant proteins might be multipurpose leptospiral proteins that participate in bacterial invasion.

Materials and Methods

Leptospira strains.

The non-pathogenic L. biflexa serovar Patoc strain Patoc I; and the pathogenic, L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20, L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae strain RGA, L. interrogans serovar Canicola strain Hond Utrecht IV, L. interrogans serovar Pomona strain Pomona, L. interrogans serovar Hardjo strain Hardjo-prajitno, L. borgpetersenii serovar Whitticombi strain Whitticombi, L. kirschneri serovar Cynopteri strain 3522 CT, L. kirschneri serovar Grippotyphosa strain Moskva, and L. noguchii serovar Panama strain CZ214 were used. Strains were cultured at 28°C under aerobic conditions in liquid Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris medium (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with 10% rabbit serum, enriched with 0.015% l-asparagine, 0.001% sodium pyruvate, 0.001% calcium chloride, 0.001% magnesium chloride, 0.03% peptone, and 0.02% meat extract.21

Extracellular matrix and biologic components.

Laminin, collagen, plasma, cellular and proteolytic fragments of fibronectin (70, 45, and 30 kDa), elastin, vitronectin, complement, and control protein fetuin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Laminin-1 and collagen type IV were derived from the basement membrane of Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma; cellular fibronectin was derived from human foreskin fibroblasts; plasma and proteolytic fragments of fibronectin, vitronectin, and human complement serum were isolated from human plasma; elastin was derived from human aorta; and collagen type I was isolated from rat tail. Native PLG, purified from plasma human, and factor H were obtained from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (San Diego, CA). C4BP, isolated from normal human serum, was obtained from Complement Technology, INC. (Tyler, TX).

Microscopic agglutination test.

The microscopic agglutination test (MAT) was performed according to Faine and others.3 In brief, 20 serovars of Leptospira spp. were used as antigens: Australis, Autumnalis, Bataviae, Canicola, Castellonis, Copenhageni, Cynopteri, Djasiman, Grippotyphosa, Hardjo, Hebdomadis, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Javanica, Panama, Patoc, Pomona, Pyrogenes, Sejroe, Tarassovi, and Wolffi. All strains were maintained in liquid Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris medium at 29°C. A laboratory-confirmed case of leptospirosis was defined by the demonstration of a four-fold increase in micro-agglutination titer between paired serum samples. The probable predominant serovar was considered to be the one with the highest dilution that could cause 50% of agglutination. The MAT result was considered negative when the titer was < 100.

In silico analysis of proteins.

Putative coding sequences (CDSs) LIC11009, LIC11360 and LIC11975 were identified in the L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni genome6,7 and selected based on their cellular localization predicted by PSORT4 (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp), and CELLO22 (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/) programs. Locations predicted by these programs are cytoplasmic, cytoplasmic membrane, periplasmic, outer membrane, and extracellular (by PSORT), and cytoplasmic, periplasmic, outer membrane, inner membrane, and extracellular (by CELLO). The SMART23 (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and PFAM24 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/) web servers were used to search for predicted functional and structural conserved domains, and LipoP5 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/LipoP/) and SignalP25 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) programs were used to evaluated the presence of lipobox/signal peptide putative sequences. Conservation of CDSs was performed by BLAST26 using Conserved Domain Database.27 CLUSTAL 2.1 multiple sequence alignment (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) was used to generate the phylogram for each CDS.28

DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction analysis.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20 cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 11,500 × g for 30 minutes and gently washed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice. Genomic DNA was isolated from the pellets by using the guanidine-detergent lysing method with DNAzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 648-basepair LIC11009, the 602-basepair LIC11360, and the 978-basepair LIC11975 DNA fragments were amplified using oligonucleotides designed according to L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni genome sequences (GenBank accession no. AE016823) and are shown in Table 1. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a reaction volume of 25 μL containing 100 ng of genomic DNA, 1 × PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM of each specific primer, 200 μM of each dNTP, and 1 unit of Taq polymerase. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 4 minutes; followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 50 seconds, 59°C (LIC11009)/64°C (LIC11360)/51°C (LIC11975), for 50 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes; and a final extension cycle at 72°C for 7 minutes. Amplicons were loaded on a 1% agarose gel for electrophoresis and visualization with GelRed™ (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA).

Table 1.

Gene locus, protein name, GenBank reference sequence number, features, sequence of the primers used for DNA amplification, and molecular mass of expressed recombinant proteins of Leptospira interrogans

| Gene locus* | Recombinant protein | GenBank accession number† | Genome annotation | Sequence of primers for polymerase chain reaction amplification and restriction cloning sites‡ | Recombinant protein molecular mass (kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIC11009 | Lsa26 | AAS69619.1 | Leptospira conserved hypothetical protein | F:5′-CTCGAGGAAGGTTGGGCAGTAGTAAAATT-3′ (Xho I); R:5′-AAGCTTTCACTTTTTCAAATCGGTATAAAC-3′ (Hind III) | 25.66 |

| LIC11360 | Lsa23 | AAS69961.1 | Lipoprotein, probable | F:5′-GGATCCGAACTTCCTTACTTTTCCCCTAAC-3′ (BamH I); R:5′-AAGCTTGAATGTTGACTAGAGGCATTTACT-3′ (Hind III) | 22.53 |

| LIC11975 | Lsa36 | AAS70551.1 | Outer membrane protein | F:5′-CTCGAGGAATGTAGCGGTGCGG-3′ (Xho I); R:5′-AAGCTTTCATCCCAAAAGATAATTCA-3′ (Hind III) | 36.12 |

F = forward; R = reverse. Restriction cloning sites are underlined.

Gene cloning and recombinant protein expression and purification.

Predicted CDSs LIC11009, LIC11360 and LIC11975 were amplified, without signal peptides, by the PCR from L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20 genomic DNA using the specific primer pairs shown in Table 1. Gel-purified PCR fragments (Illustra GFX PCR DNA and Gel band purification kit; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp, Piscataway, NJ) were subcloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, Prodimol, Minas Gerais, Brazil) and cloned into the pAE29 expression vector at XhoI and HindIII (LIC11009 and LIC11975) or BamHI and HindIII restriction sites (LIC11360). The pAE vector enables expression of recombinant proteins with a minimal 6XHis-tag at the N-terminus. All cloned sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing with an ABI 3100 automatic sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Protein expression of recombinant proteins was performed in the Escherichia coli BL21 (SI) strain by action of T7 DNA polymerase under control of the osmotically induced promoter proU.30 Escherichia coli BL21 (SI) host cells were transformed with the recombinant plasmids and grown at 30°C in Luria-Bertani broth without NaCl and with 100 μg/mL of ampicillin with continuous shaking until an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 0.6–0.8 was reached. Recombinant protein synthesis was induced for 3 hours by addition of 300 mM (rLIC11360 and rLIC11975) or 150 mM (rLIC11009) NaCl. Bacterial cells were then harvested by centrifugation, and bacterial pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (200 μg/mL of lysozyme, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and lysed on ice with a cell disruptor (Ultrasonic Processor; GE Healthcare). Insoluble fractions were resuspended in a buffer containing 100 mM Tris, pH 12.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 8 M urea for rLIC11360 or 100 mM Tris-HCl or Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 8 M urea for rLIC11009 and rLIC11975, using buffer pH of 8.0 and 12.0, respectively.

Recombinant proteins were purified by using metal chelating chromatography in a Sepharose fast flow column (GE Healthcare). The rLIC11360 protein was refolded by diluting 1:500 with 100 mM Tris, pH 12.0, and 500 mM NaCl before chromatographic purification. The rLIC11009 and rLIC11975 proteins were refolded in a column by gradually removing urea (4 to 0 M). Fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyarylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 15% polyacrylamide gel and fractions that contained recombinant proteins were extensively dialyzed against Tris-NaCl, pH 12.0 containing 0.1% glycine for rLIC11360 and rLIC11975, and PBS containing 0.1% glycine for rLIC11009.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Recombinant proteins Lsa26 and Lsa36 were dialyzed against sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and recombinant protein Lsa23 was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris, pH 12.0. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy measurements were performed at 20°C by using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Japan Spectroscopic, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Peltier unit for temperature control. Far-ultraviolet CD spectra were measured by using a 1-mm path-length cell at 0.5-nm intervals. Spectra are presented as an average of five scans recorded from 185 to 260 nm. Residual molar ellipticity is expressed in degree X centimeter per decimole. Spectra data were analyzed by using K2D3 software (http://www.ogic.ca/projects/k2d3/) and the method that calculated the secondary structure content from the experimental data.31

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of human antibodies.

Human IgG against Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 was detected by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described.32 In brief, positive MAT serum samples from 16 confirmed-leptospirosis patients were diluted 1:200 and evaluated for total IgG by using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibodies (1:5,000) (Sigma-Aldrich). Data were analyzed by using Graph Pad Prism software version 3.0 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA). The cutoff value for each recombinant protein was calculated as described by Flannery and others,33 and defined as the absorbance value for the 96th percentile of two commercial pools of healthy human sera (Sigma-Aldrich and Complement Tech.).

Antiserum.

Five female BALB/c mice (4–6 weeks old) were immunized subcutaneously with 10 μg of the recombinant proteins adsorbed in 10% (v/v) Alhydrogel (2% Al(OH)3; Brenntag Biosector, Frederikssund, Denmark) used as adjuvant. Two subsequent booster injections were given at two-week intervals with the same recombinant proteins preparation. Negative control mice were injected with PBS plus Alhydrogel. Two weeks after each immunization, the mice were bled from the retro-orbital plexus and pooled serum was analyzed by ELISA for determination of antibody titers.

Immunoblotting assay.

The purified recombinant proteins subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel and transferred into nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; GE Healthcare) in semi-dry blotting equipment (GE Healthcare). Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C with 10% non-fat dried milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then incubated with anti-Lsa26, anti- Lsa23, anti-Lsa36 mouse serum diluted 1:50, or mouse anti-His tag monoclonal antibody (GE Healthcare) diluted 1:1,000 for 3 hours at room temperature. After washing, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS- T with non-fat milk for 1 hour. Protein reactivity was determined by using the ECL reagent kit chemiluminescence substrate (GE Healthcare) with subsequent exposure to x-ray film or using Carestream Molecular Imaging connected to Gel Logic 2200PRO (Equilab, Whitestone, NY).

Distribution of proteins among leptospiral strains.

Bacterial cultures of Leptospira spp. were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times with PBS containing 5 mM MgCl2, and resuspended in PBS containing 9% SDS. Purified recombinant proteins or protein extracts from leptospires were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; GE Healthcare) in semi-dry blotting equipment (GE Healthcare), and analyzed as described above.

Proteinase K accessibility assay.

Enzymatic digestion was performed as described by Oliveira and others14 with some modifications. In brief, 5-mL suspensions of live leptospires (L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20)/per each treatment (approximately 108 cells/mL) were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature and washed once with PBS low salt containing 50 mM NaCl (PBS ls). Leptospires were resuspended in 5 mL of proteolysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM CaCl2) containing 25 μg/mL of proteinase K (PK) (Sigma-Aldrich). Test tubes were incubated for 0–240 minutes at 37°C and aliquots were obtained at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes before the addition of 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride to stop PK activity. Suspensions were subsequently centrifuged at 11,500 × g for 5 minutes, washed twice with PBS ls, and resuspended in PBS ls for an ELISA with antibodies against Lsa26, Lsa23, Lsa36, LipL32, and DnaK, as described below. LipL32 and DnaK are membrane34 and cytoplasmic35 leptospiral proteins and were used in our experiment as positive and negative controls, respectively.

ELISA for cellular localization detection of proteins.

Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20 (approximately 107 cells/well) were coated onto microplates (Costa High Binding; Corning, Tewksbury, MA) and allowed to stand at room temperature for 16 hours. The plates were washed three times with PBS ls and blocked for 2 hours at 37°C with PBS ls containing 5% non-fat dry milk and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). After incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with polyclonal mouse anti-serum against rLIC11009, rLIC11360, rLIC11975, LipL32, or DnaK (dilution of an OD = 1) the leptospires were washed three times with PBS ls and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with 50 μL of a 1:5,000 dilution of HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS ls. The wells were washed three times with PBS ls and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich) (1 mg/mL) in citrate phosphate buffer, pH 5.0, plus 1 μL/mL of H2O2 was added (100 μL/well). The reaction proceeded for 15 minutes and was stopped by the addition of 50 μL of 4 N H2SO4. The absorbance at 492 nm was determined in a microplate reader (Multiskan EX; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Helsinki, Finland) against the OD of blanks that contained the reaction mixture except for antibodies against the recombinant proteins. For statistical analyses, binding of polyclonal mouse anti-serum against Lsa26, Lsa23, Lsa36, LipL32, or DnaK at 0 hours of incubation was compared with other incubations by using Student's two-tailed t-test.

Interaction of recombinant proteins with ECM and plasma components.

Protein attachment to individual macromolecules of the ECM and plasma components was analyzed according to a published protocol11 with some modifications. In brief, 96-well plates were coated with 1 μg of laminin, collagen type I, collagen type IV, cellular fibronectin, plasma fibronectin, fibronectin proteolytic fragments (30 kDa, 45 kDa, and 70 kDa), elastin, vitronectin, human PLG, complement mixture, factor H, C4BP, BSA, gelatin (negative controls) or fetuin (highly glycosylated attachment; negative control protein) in 100 μL of PBS for 3 hours at 37°C. The wells were washed three times with PBS-T and blocked with 200 μL of PBS-T containing 10% (w/v) non-fat dry milk for 1 h at 37°C, followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C. One microgram of each recombinant protein was added per well in 100 μL of PBS, and protein was allowed to attach to the different substrates for 90 minutes at 37°C. After washing six times with PBS-T, bound recombinant proteins was detected by adding an appropriate dilution (OD492nm = 1.0) of mouse anti-recombinant proteins in 100 μL of PBS as follows: Lsa26, (1:1,000), Lsa23 and Lsa36 (1:500). Incubation proceeded for 1 h at 37°C. After three washings with PBS-T, 100 μL of a 1:5,000 dilution of HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS was added per well and samples were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed three times and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich) (1 mg/mL) in citrate phosphate buffer, pH 5.0, plus 1 μL/mL of H2O2 was added (100 μL/well). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 15 minutes and stopped by the addition of 50 μL of 4 N H2SO4. Readings were taken at 492 nm in a microplate reader (Multiskan EX; Thermo Fisher).

For statistical analyses, the binding of recombinant proteins to ECM macromolecules and plasma components was compared with its binding to BSA, fetuin, and gelatin by using Student's two-tailed t-test, and P values were given related to comparison to fetuin, which was used as a negative control for the following experiments. Bindings were also confirmed in another assay that used HRP-conjugated mouse anti-His tag monoclonal antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) previously titrated against the recombinant protein and used at a dilution that had an OD492 nm = 1.0 (1:10,000).

Dose-response curves.

For determination of dose-dependent attachment of recombinant proteins to ECM macromolecules and plasma components, ELISA plates were coated with 100 μL of 10 μg/mL of ECM and plasma components and allow to adhere for 3 hours at 37°C. Plates were then washed with PBS-T and blocked for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C. Increasing concentrations of the purified recombinant proteins in PBS (100 μL/well) were added and incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C. Assessment of bound protein was performed by incubation for 1 hour at 37°C with antiserum raised against recombinant proteins, followed by HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG, as described above. The ELISA data were used to calculate the dissociation constant (KD) according to the method described36 based on the equation KD = (Amax [protein])/A) – [protein], where A is the absorbance at a given protein concentration, Amax is the maximum absorbance for the ELISA plate reader (equilibrium), [protein] is the protein concentration, and KD is the dissociation equilibrium constant for a given absorbance at a given protein concentration (ELISA data point).

Characterization of protein binding to plasma fibronectin and PLG.

To determine the role of lysine in PLG-recombinant proteins interactions, the lysine analog 6-aminocaproic acid (ACA) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added with recombinant proteins at a final concentration of 2 mM or 20 mM to PLG-coated wells. The capacity of heparin to compete for binding of rLIC11360 and rLIC11975 to plasma fibronectin proteolytic fragments F70 and F30 was performed by incubating 1 μM of recombinant proteins with different concentrations of heparin (0–350 IU) (Sigma-Aldrich); mixtures were then added to the F70- or F30-coated wells. In both experiments, detection of bound recombinant proteins was performed as described above.

PLA enzymatic activity assay.

Ninety-six well ELISA plates were coated overnight with 10 μg/mL of recombinant proteins or BSA (negative control) in 100 μL of PBS at 4°C. Plates were washed once with PBS-T and blocked for 2 hours at 37°C with PBS with 10% (w/v) non-fat dry milk. The blocking solution was discarded and 100 μL/well of 10 μg/mL human PLG was added, followed by incubation for 2 hours at 37°C. Wells were washed three times with PBS-T, and 4 ng/well of human urokinase-type PLG activator (uPA; Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Subsequently, 100 μL/well of PLA-specific substrate D-valyl-leucyl-lysine-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was added at a final concentration of 0.4 mM in PBS. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and substrate degradation was measured by taken the readings in a microplate reader at 405 nm.

Ethics.

All animal studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, under protocol number 768/10. This Committee adopts the guidelines of the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation. Confirmed leptospirosis human serum samples were obtained from the Instituto Adolfo Lutz collection, Santos, SP, Brazil. Samples were used for research purposes only.

Statistical analysis.

All results are expressed as means ± SD. Student's paired t-test was used to determine the significance of differences between means, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Bioinformatics of the coding sequences.

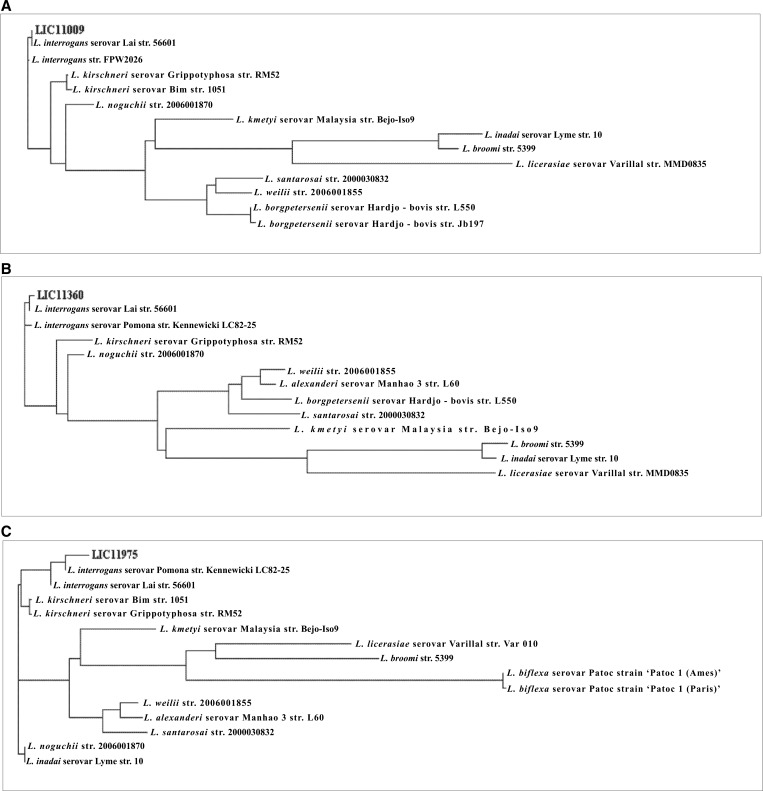

The genes LIC11009, LIC11360, and LIC11975 were identified by analysis of the genome sequences of the chromosome I of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni; each gene is present as a single copy.7 The CDSs LIC11009, LIC11360, and LIC11975 are predicted to be outer membrane proteins based on PSORT4 and for LIC11975 and LIC11009 also by CELLO22 programs. No putative conserved domains have been detected by BLAST.26,37 BLAST analysis of the three CDSs showed that they are present in several strains of Leptospira spp. In the case of LIC11975, a sequence with partial similarity (38%) was identified in the saprophytic strains of L. biflexa, Patoc 1 (Ames) and Patoc 1 (Paris). Multiple sequence alignment was performed with the CLUSTAL 2.128 program comparing the CDSs LIC11009 (Figure 1A), LIC11360 (Figure 1B), and LIC11975 (Figure 1C) with sequences available in GenBank. The depicted phylograms clearly show that the three coding sequences are well conserved among several pathogenic strains of Leptospira. In the case of LIC11975, similarity/proximity with the sequence present in pathogenic strains is shown; the sequences present in saprophytic strains have lower similarity and are organized in a more distant branch (Figure 1C). General features of Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 are summarized in Table 1. The CDSs have been identified by proteomics in L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain FIOCRUZ L1-130, but only in the case of LIC11009 could the number of copies per cell be determined (2,566), and LIC11360 and LIC11975 are probably expressed in amounts below the detection limit of the method.38

Figure 1.

Analysis of LIC11009, LIC11360, and LIC11975 coding sequence conservation among strains of Leptospira spp. by Clustal W2 alignments. Blast analyses were assessed among sequences in GenBank, and leptospiral sequences were used to perform sequence alignment. Phylograms of all sequence alignments show the proximity of LIC11009 (A), LIC11360 (B), and LIC11975 (C) within pathogenic strains of Leptospira spp. The distant branches show the saprophytic strains.

Expression, purification, and identification of recombinant proteins.

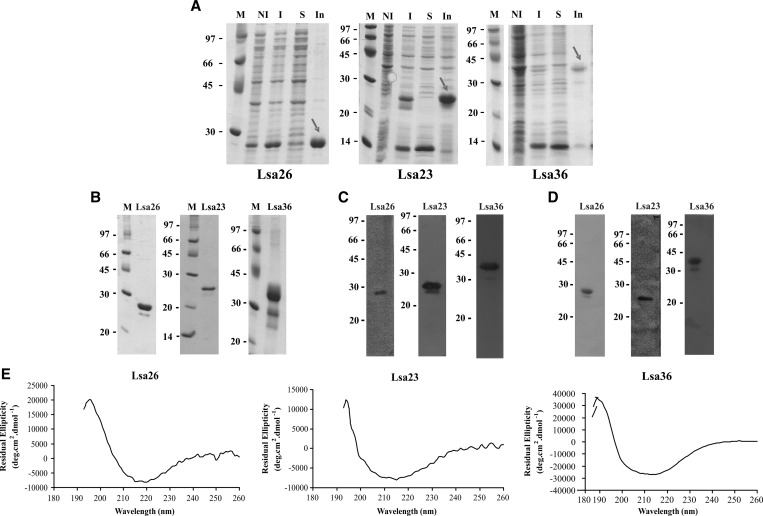

The amplified coding sequences, excluding the signal peptide sequences, were cloned and expressed as full-length proteins in E. coli and carried a 6XHis tag at the N-terminal. Gene locus, protein reference number, given name, sequences of primers used for PCR amplifications and molecular mass of recombinants are shown in Table 1. The recombinant proteins were expressed in insoluble form, purified under denaturing conditions by nickel-affinity chromatography, followed by refolding. An aliquot of each step of the process was analyzed by SDS-PAGE for the proteins (Figure 2A). The purified proteins were represented by major bands (Figure 2B), but in the case of Lsa36, other protein bands of lower molecular mass were also present, probably because of degradation during the purification step. To further confirm that these proteins are His-tag recombinants, we conducted immunoblotting and probed samples with monoclonal mouse His-tag antibodies (GE Healthcare). Results are as shown in Figure 2C. Anti-His tag antibodies recognized the three recombinant proteins. Similar data were obtained when blotted recombinant proteins were probed with the respective polyclonal antiserum raised in mice (Figure 2D). Structural integrity of the purified proteins was assessed by CD spectroscopy. This method evaluates the secondary structure content of protein and is important data to obtain after protein refolding. The CD spectra for the three proteins are shown in Figure 2E. Analysis of the spectra data by K2D331 software showed 43.15% β strand and 3.27% alpha helix for Lsa26, 35.95% β strand and 9.5% alpha helix for Lsa23, and 8.34% of β strand and 55.67% alpha helix for Lsa36. These data validate protein integrity for further studies.

Figure 2.

Analysis of recombinant proteins of Leptospira interrogans by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and staining with Coomassie blue, Western blotting, and circular dichroism. A, Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 expression from NaCl-induced Escherichia coli BL21-SI. M = molecular mass marker; NI = non-induced total bacterial extract; I = total bacterial cell lysates after induction; S = soluble fraction of the induced culture in the presence of 8 M urea; In = insoluble fraction of the induced culture. B, Purified recombinant proteins. C and D, Western blotting analyses of the recombinant proteins probed with monoclonal anti-His tag antibodies (1:1,000) (C) and correspondent antiserum produced in mice against each recombinant protein (diluted 1:5,000) (D). ECD spectra of Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 recombinant proteins are depicted after refolding. Far-ultraviolet CD spectra are shown as an average of five scans from 185 to 260 nm (E).Values on the left are in kilodaltons.

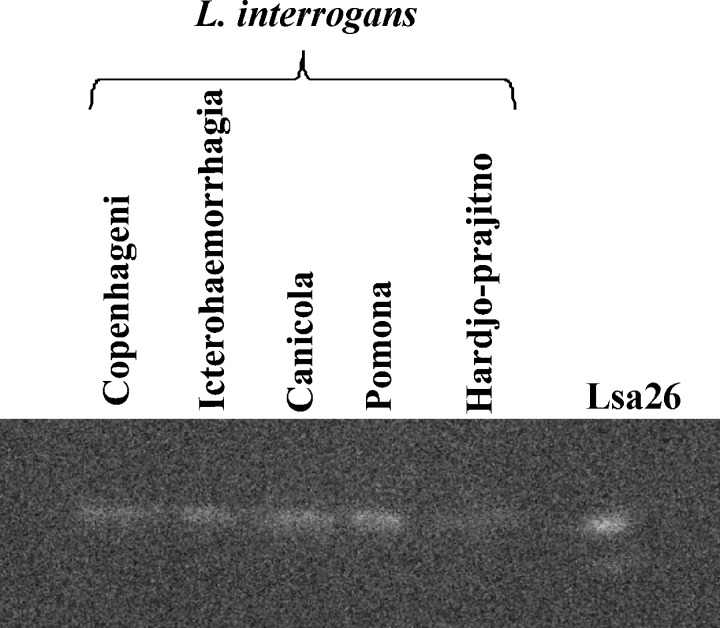

Protein distribution among leptospiral strains.

Protein expression and conservation among Leptospira strains was assessed with total protein extracts of pathogenic strains of Leptospira spp. and the non-pathogenic strain L. biflexa serovar Patoc. Cell extracts were gel fractionated, proteins blotted onto membranes, and probed with the respective polyclonal antiserum raised in mice. Proteins Lsa23 and Lsa36 were not identified in any leptospiral protein extracts assayed by Western blotting. Protein Lsa26 was detected in the bacterial extracts of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20, L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae strain RGA, L. interrogans serovar Canicola strain Hound Utrech IV, L. interrogans serovar Pomona strain Pomona, and L. interrogans serovar Hardjo strain Hardjo-prajitno (Figure 3). This protein was not identified in the extracts of the pathogenic L. borgpetersenii serovar Whitticombi strain Whitticombi, L. kirschneri serovar Cynopteri strain 3522 CT, L. kirschneri serovar Grippotyphosa strain Moskva, L. noguchii serovar Panama, and saprophytic L. biflexa serovar Patoc strain Patoc.

Figure 3.

Protein distribution (Lsa26) among strains of Leptospira interrogans. Whole bacterial cell lysates and Lsa26 were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Antiserum against recombinant Lsa26 was used as probe (diluted 1:50). Reactivity was shown by using an ECL reagent kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and subsequent exposures with Gel Logic 2200 equipment (Equilab, Whitestone, NY). Recombinant protein Lsa26 was used as a marker.

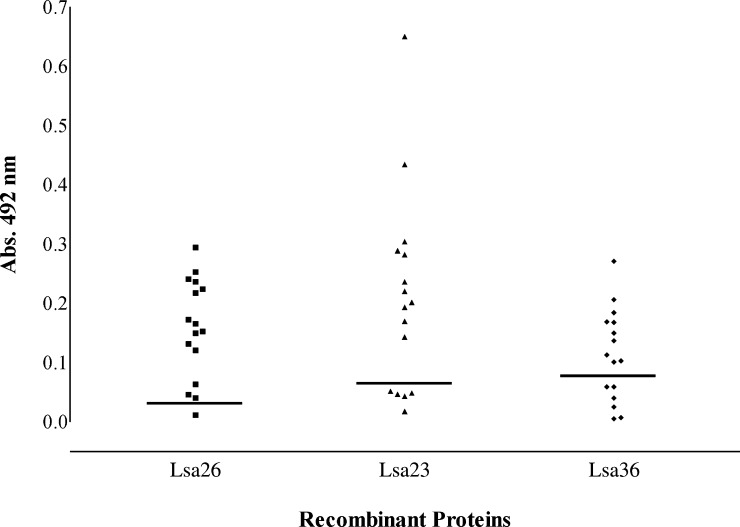

Reactivity of recombinant proteins with serum from patients with leptospirosis.

To investigate whether LIC11009, LIC11360, and LIC11975 leptospiral coding sequences are capable of promoting an immune response from an infected host, we evaluated the reactivity of the recombinant proteins by determining the amount of corresponding IgG present in serum samples of patients with leptospirosis. We performed an ELISA using 16 serum samples and calculated the cutoff value, as described the Materials and Methods. The results shown in Figure 4 indicate that three proteins reacted with the serum samples; Lsa26 had the highest number of responders (93.8%), followed by Lsa23 (68.8%) and Lsa36 (62.5%). Our data suggest that the proteins are expressed during leptospiral infection.

Figure 4.

Reactivity of recombinant proteins Lsa26, Lsa23 and Lsa36 of Leptospira interrogans with serum samples of persons given a diagnosis of leptospirosis. Positive serum samples (responders) were determined by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with recombinant proteins and serum samples from patients. Reactivity was evaluated as total IgG. The cutoff value (horizontal lines) for each recombinant protein was defined as the absorbance (Abs.) value for the 96th percentile of two commercial pools of healthy human serum.

Cellular localization of Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 by protease assays.

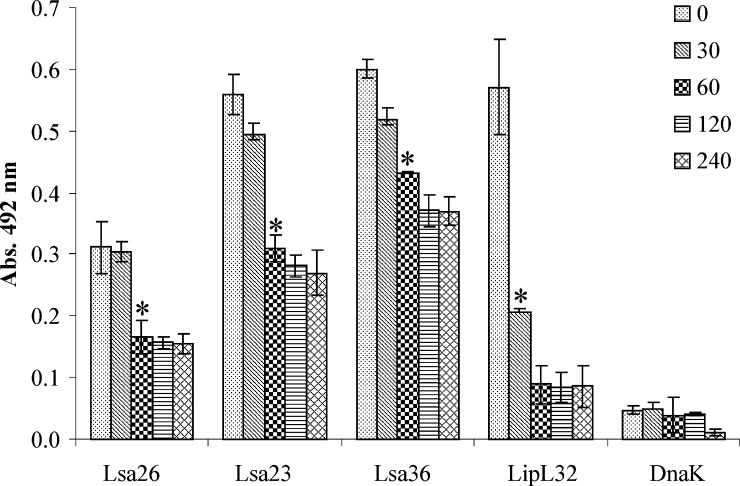

We performed a proteinase K accessibility assay by using a described assay14,39 with some modifications. Live L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20 was treated with 25 μg/mL of proteinase K, and aliquots of the bacterial suspensions were obtained at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes. The suspensions were centrifuged and resuspended bacteria were used to coat microplates, followed by incubation with polyclonal antibodies against each protein, including the controls, LipL32 and DnaK, for outer34 and cytoplasmic35 protein, respectively. Proteins Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 were susceptible to protease treatment and showed statistically significant values after 60 minutes of incubation, when compared with 0 min control samples (Figure 5). Protein remaining was 53%, 55%, and 72% for Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36, respectively, contrasting with 36% of the major control protein LipL32 that remained intact after only 30 minutes of incubation. Nearly no reduction was observed for the DnaK cytoplasmic protein (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Protease accessibility assay of LIC11009, LIC11360 and LIC11975 coding sequences of Leptospira interrogans. Viable L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M-20 were incubated with 25 μg/mL of proteinase K at the indicated times (in minutes). Suspensions were centrifuged, washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, coated onto a microplate. Antibodies against Lsa26, Lsa23 Lsa36 were used. Antiserum against the outer membrane protein LipL32 and the cytoplasmic leptospiral protein DnaK were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Parallel blanks were run without antibodies against the recombinant proteins. Bars represent the mean ± SD absorbance of three replicates for each protein and are representative of two independent experiments. For statistical analyses, the optical density value after treatment with proteinase K was compared with the value at 0 hours incubation by a two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.05).

Adhesion of Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 proteins to ECM components.

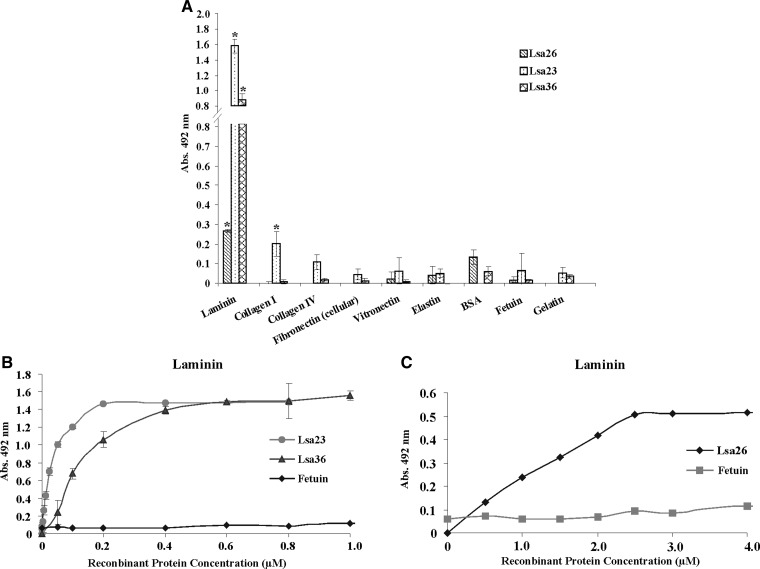

The Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 proteins are probably surface exposed. We evaluated whether they could mediate host colonization by adhering to extracellular matrix proteins. Thus, laminin, collagen type I, collagen type IV, cellular fibronectin, vitronectin, elastin, and control proteins BSA, fetuin, and gelatin were immobilized on 96-well micro-dilution plates, and recombinant protein attachment were assessed by using an ELISA, as described by Atzingen and others.11 As shown in Figure 6A, the three proteins exhibited statistically significant adhesiveness to laminin (P < 0.05), and Lsa23 also showed significant binding to collagen I. These proteins were then referred to as Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 (leptospiral surface adhesion) and their molecular masses were determined (Table 1). No statistically significant adhesiveness was observed with the three recombinant proteins when wells were coated with collagen type IV, cellular fibronectin, vitronectin, elastin, BSA, gelatin, or the highly glycosylated control fetuin.

Figure 6.

Interaction of recombinant proteins of Leptospira interrogans with extracellular matrix (ECM) components. A, One microgram of ECM macromolecules was coated onto enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microplates wells after incubation with 1 μg of Lsa26, Lsa23, or Lsa36. Bovine serum albumin, gelatin, and fetuin were used in the place of ECM as negative controls for nonspecific binding. Binding was evaluated by ELISA. Bars represent the mean ± SD absorbance at 492 nm of three replicates for each protein and are representative of two independent experiments. For statistical analyses, the interaction of recombinant proteins with ECM was compared with its binding to fetuin by two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.05). B and C, Lsa23 and Lsa36, and Lsa26 dose-dependent binding experiments with laminin, respectively. Binding was detected by polyclonal antibodies against each recombinant protein; fetuin was included as a negative control. Dissociation constant data are shown in Table 2.

The interaction between the proteins and laminin was also assessed on a quantitative basis by varying protein concentration, as shown in Figure 6B and C. A dose-dependent and saturable binding was observed when increasing concentrations of the recombinant protein from 0 to1 μM for Lsa23 and Lsa36 (Figure 6B) and from 0 to 4 μM for Lsa26 (Figure 6C) were allowed to adhere to a fixed laminin concentration (1 μg). Binding saturation level was reached with protein concentrations of 0.2, 0.6, and 2.5 μM for Lsa23, Lsa36, and Lsa26, respectively. Calculated KD values are shown in Table 2. Binding of the proteins to laminin was also detected when monoclonal mouse anti-polyhistidine antibodies were used to probe the attachment to laminin. Binding of Lsa23 to collagen I detected in the screening assay shown in Figure 6A was not confirmed when the reaction was evaluated in a quantitative manner.

Table 2.

Dissociation constants for binding of recombinant proteins with Leptospira interrogans extracellular matrix and plasma components*

| Proteins | Lsa26 (nM) | Lsa23 (nM) | Lsa36 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laminin | 952.2 ± 418.9 | 25.1 ± 4.1 | 120.8 ± 97.6 |

| Plasma fibronectin | – | 528.7 ± 143.5 | 34.8 ± 10.4 |

| F70 | – | ND | 5.1 ± 1.2 |

| F30 | – | ND | 24.5 ± 2.9 |

| Plasminogen | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 11.7 ± 1.4 | 17.8 ± 5.5 |

| C4BP | – | 17.6 ± 3.5 | – |

| Factor H | – | ND | – |

Values are mean ± SD. – = non-reactive; ND = not determined.

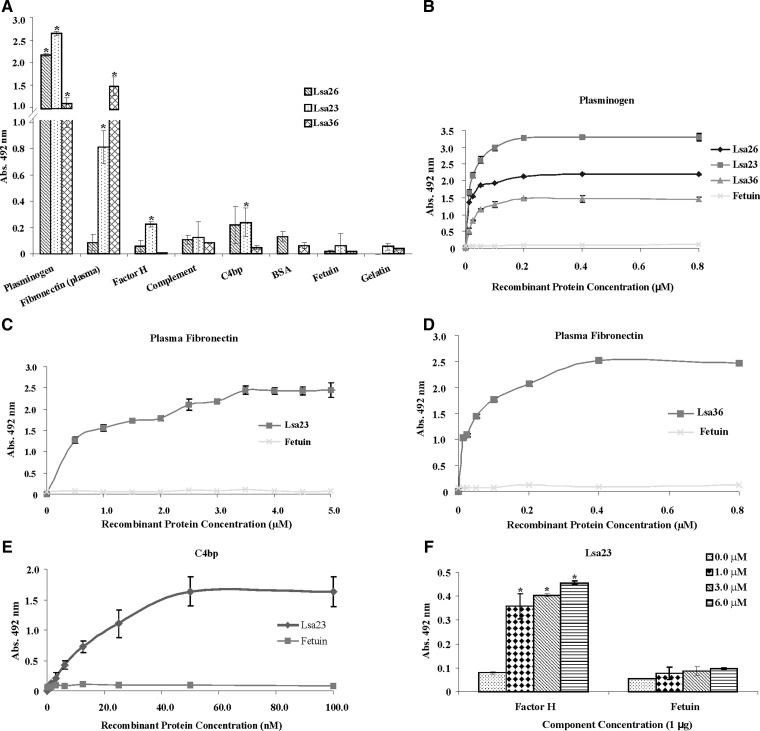

Binding of human plasma components by Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36.

Previous work by our group has shown that several proteins may probably act as PLG receptors.8,15,16,20,40 We have also described leptospiral proteins that in addition to binding PLG can also interact with the complement regulator C4BP.17,18 We evaluated whether the Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 proteins could can also interact with plasma components in vitro. Our data showed that the three proteins bound human PLG (P < 0.05), Lsa23 and Lsa36 bound fibronectin (P < 0.05), and Lsa23 interacted with the complement regulators factor H (P < 0.05) and C4BP (P < 0.05) (Figure 7A). None of the proteins interacted significantly with BSA, fetuin, or gelatin control proteins (Figure 7A). Binding between the recombinant proteins and PLG is dose-dependent and saturable when increasing concentrations of the recombinant proteins (0–0.8 μM) were allowed to react with a fixed (1 μg) PLG concentration (Figure 7B). The reaction equilibrium was reached at protein concentration of 0.2 μM, and the calculated dissociation constants are shown in Table 2. Binding of Lsa23 and Lsa36 to plasma fibronectin is dose-dependent when increasing concentrations of the recombinant protein Lsa23 (0–5.0 μM) (Figure 7C) or Lsa36 (0–0.8μM) (Figure 7D) were allowed to react with a fixed (1 μg) fibronectin concentration. The reaction saturation was reached at protein concentration of 3.5 and 0.4 μM for Lsa23 and Lsa36, respectively, and the calculated dissociation constants are shown in Table 2. The interaction of Lsa23 with the complement regulators C4BP and factor H was dose-dependent but with distinct affinities (Figure 7E and F). Increasing Lsa23 concentration bound to a fixed concentration of C4BP (1 μg) in a dose-dependent manner; saturation was reached at an Lsa23 concentration of 50 nM (Figure 7E) and showed a dissociation constant of 17.63 ± 3.46 nM. The interaction of Lsa23 with factor H was also dose-dependent, but saturation was not reached up to the 6.0 μM recombinant protein concentration (maximum protein concentration achieved) and the OD492nm was < 0.5 (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Attachment of Lsa26, Lsa23 and Lsa36 proteins of Leptospira interrogans to plasma components. A, Wells were coated with 1 μg of each plasma component or control proteins bovine serum albumin, gelatin, and fetuin followed by incubation with 1 μg of recombinant proteins per well. Binding was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data represent the mean ± SD absorbance at 492 nm of three replicates for each protein and are representative of two independent experiments. For statistical analyses, the attachment of recombinant proteins to plasma components was compared with its binding to fetuin by two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.05). Proteins that showed reactivity were further assayed with the respective component. Dose-dependent binding experiments with plasminogen (B), plasma fibronectin (C and D), C4BP (E), and with factor H (F). One microgram of each plasma component was immobilized onto 96-well ELISA plates and increasing concentrations of each recombinant protein were added. Binding was detected by using antiserum raised in mice against each recombinant protein at an appropriate dilution. Fetuin was included as a negative control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and expressed as the mean ± SD absorbance at 492 nm for each point and are representative of two independent experiments. Calculated equilibrium constants are shown in Table 2. Attachment of Lsa23 with factor H was compared with its binding to fetuin by two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.05).

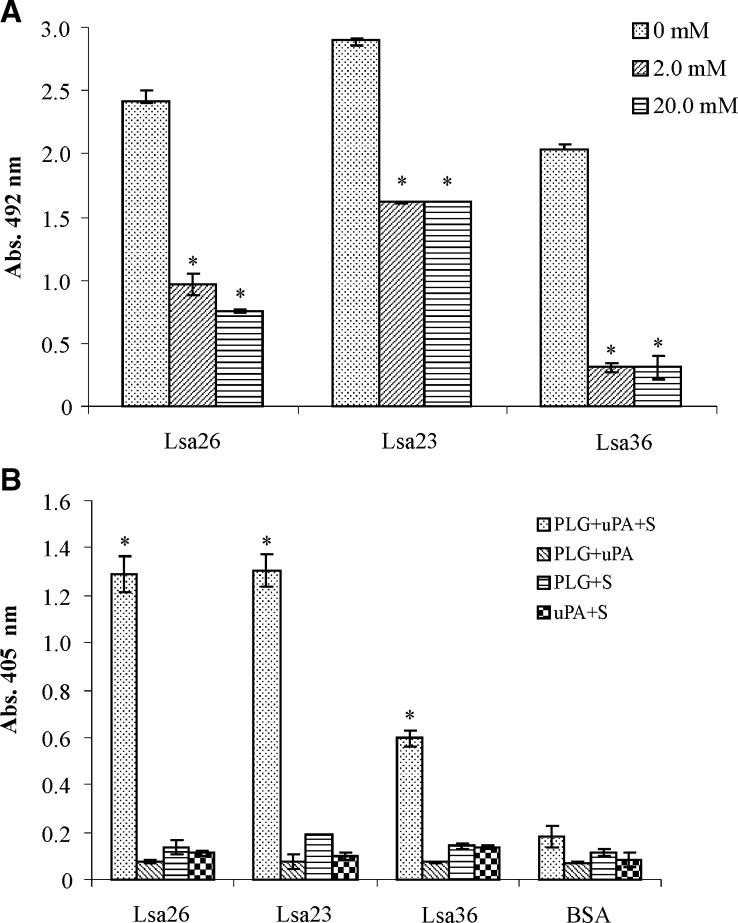

Binding of recombinant proteins to PLG via kringle domains.

The PLG kringle domains frequently participate in the interaction of lysine residues with bacterial protein receptors.41 We have shown that these domains participate in the binding of PLG with intact live L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain L1–130 because the derivative and analog of lysine, ACA, almost totally inhibited binding.19 We evaluated the participation of lysine residues in binding of the recombinant proteins to PLG by the addition of ACA to the reaction mixtures. A strong, statistically significant inhibition of the interaction of Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 with PLG was observed when 2 mM ACA was added to the reaction (Figure 8A). The results strongly suggest the participation of the kringle domains in the interaction of Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 proteins with PLG.

Figure 8.

Role of lysine residues in recombinant protein–plasminogen (PLG) interaction and generation of plasmin (PLA) in Leptospira interrogans. A, Binding of Lsa26, Lsa23, and Lsa36 (10 μg/mL) to PLG was conducted in the presence or absence (no inhibition) of the lysine analog 6-aminocaproic acid (ACA). Bound PLG was detected and quantified by specific antibodies for each recombinant protein. Bars represent the mean ± SD absorbance at 492 nm of three replicates and are representative of two independent experiments. Attachment of recombinant protein in the presence of ACA was compared with its binding to PLG in the absence of ACA by two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.05). B, PLA generation by PLG bound to recombinant proteins was assayed by using a modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Immobilized recombinant proteins were treated as follows: PLG + urokinase-type PLG activator [uPA] + specific PLA substrate (PLG + uPA + S) or controls lacking one of the three components (PLG + uPA; PLG + S; uPA + S). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a negative control. Bars represent mean ± SD absorbance at 405 nm as a measure of relative substrate degradation of three replicates for each condition and are representative of two independent experiments. Statistically significant binding was calculated in comparison with the negative control (BSA) (*P < 0.05).

Generation of PLA from PLG-bound recombinant proteins.

We have shown that enzymatically active PLA is generated by PLG bound to the surface of L. interrogans when its activator is present.19 To assess whether the PLG bound to Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 generates proteolytic activity, as reported for other recombinant proteins,8,15–17,20,40 a microplate was coated with each recombinant protein, blocked, and then incubated with PLG. Unbound PLG was removed and urokinase (uPA)–type PLG activator (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. The reaction was incubated overnight, and the PLA activity was evaluated by measuring the cleavage of the PLA-specific substrate d-valyl-leucyl-lysine-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) at 405 nm. The PLG captured by the three recombinant proteins could be converted into PLA, as indirectly demonstrated by specific proteolytic activity (Figure 8B). Negative controls without PLG, uPA, or chromogenic substrate showed no enzymatic activity.

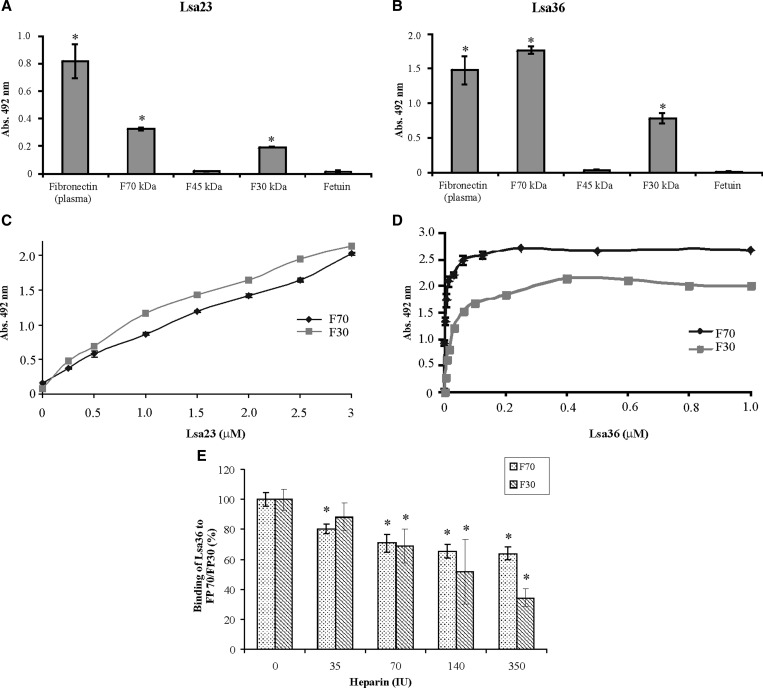

Interaction of Lsa23 and Lsa36 with F30- and F70-kDa fragments of fibronectin.

Recombinant proteins Lsa23 and Lsa36 bind to plasma fibronectin (Figure 7C and D). We further characterized this binding by evaluating the reactivity of the recombinant proteins with the F30-, F45-, and F70-kDa fragments of fibronectin. The experiments were similar to the one described for the reactivity with plasma components in which 1 μg of the protein reacted with the immobilized fragment. Interaction with the fibronectin fragments was detected with Lsa23 and Lsa36 and F30 and F70 kDa, but no attachment was seen with the F45-kDa fragment and both proteins (Figure 9A and B). Binding was analyzed in a quantitative mode in both cases, and results showed that although the reactivity of Lsa23 with F30- and F70-kDa fragments was dependent on protein concentration, equilibrium was not reached with 3 μM of Lsa23 (Figure 9C). In contrast, the reactivity of Lsa36 with the same fragments reached the saturation level at 0.25 and 0.4 μM of protein concentration with F70- and F30-kDa fragments, respectively (Figure 9D).

Figure 9.

Binding of Lsa23 and Lsa36 of Leptospira interrogans with plasma fibronectin proteolytic fragments. One microgram of proteolytic fragments F70, F45, and F30 were coated onto microtiter plates followed by incubation with 1 μg of (A) Lsa23 or (B) Lsa36. Fetuin was used as negative control for nonspecific binding. Bars represent the mean ± SD absorbance at 492 nm of three replicates for each protein and are representative of two independent experiments; the attachment of recombinant proteins to proteolytic fragments was compared with its binding to fetuin by two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.005). C and D, dose-dependent binding experiments of Lsa23 and Lsa36, respectively, with F70 and F30; each experiment was performed in triplicate and results expressed as the mean ± SD absorbance 492 nm for each point. Dissociation constants are shown in Table 2. E, Inhibition of Lsa36 interaction with F70 and F30 by heparin. Attachment of Lsa36 (1 μg) to fixed F70 and F30 concentration was performed in the presence of increasing amounts of heparin (0–350 IU). Attachment of Lsa36 in the presence of heparin was compared with its binding to each proteolytic fragments without heparin (0 IU) by two-tailed t-test (*P < 0.05).

Because F30- and F70-kDa fibronectin proteolytic fragments bind heparin, we analyzed the effect of increasing concentration of heparin (0–350 IU) on binding of Lsa36 and Lsa23 to both fragments. Our results showed that heparin inhibited the binding of Lsa36 to F30- and F70-kDa fragments in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 9E). Binding reduction was statistically significant (P < 0.05) with 35 IU of heparin for the binding of Lsa36 to F70-kDa fragment. For Lsa36 with the F30-kDa fragment, reduction was achieved with 70 IU of heparin. No competition was observed for Lsa23.

Discussion

Whole genome sequencing of a pathogen provides access to its full antigenic collection. Genomics has catalyzed a shift in vaccine development towards sequence-based reverse vaccinology approaches that use in silico screening of the entire genome to identify genes that encode proteins with the features of antigen targets.42 Furthermore, this process has led to identification of several new virulence factors in important pathogens, such as the factor H binding protein of Neisseria meningitides,43 and several putative transcriptional regulators of Streptococcus pneumoniae.44 We have investigated the genome sequences of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni and have identified several proteins that are potentially involved in pathogenesis. We have used the criterion of cellular location and selected the proteins that are probably surface exposed.

In these studies, we selected three predicted membrane proteins of the Leptospira (annotated as Leptospira conserved hypothetical protein, probable lipoprotein, and outer membrane protein for LIC11009, LIC11360 and LIC11975, respectively), with no assigned function (http://bioinfo03.ibi.unicamp.br/leptospira/). Bioinformatics analysis of CDSs LIC11009, LIC11360, and LIC11975 showed that these sequences are diverse and show a high percentage of identity among pathogenic strains of Leptospira. However, only Lsa26 (LIC11009) was detected in protein extracts of serovars of L. interrogans by Western blotting. This finding could be explained by the fact that 2,566 copies/cell of this protein were estimated by quantitative proteomics, but Lsa23 and Lsa36, although identified, have their number of copies below the detection limit,38 indicating their low level of protein expression in leptospires. The differential expression of proteins during infection was also shown by the reactivity with serum samples from an infected host, in which the highest number of responders was detected with Lsa26.

The interaction of pathogens with ECM has been well documented,45 and our group has reported the attachment of L. interrogans to several ECM components.8–18 Several laminin-binding proteins were identified, which indicated that leptospires have a redundant repertoire of adhesion molecules that are probably part of their invasion strategies. Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 bind laminin in a dose-dependent, specific, and saturable manner, fulfilling the properties of receptor-ligand interaction. The high affinity of Lsa23 to laminin (KD = 25.08 ± 4.1 nM), a value of the same order of magnitude as a described Lsa66 adhesin.15 The KD values of Lsa26 and Lsa36 are similar to the ones described for LenB,46 TlyC,47 OmpL37,48 Lsa20,16 Lsa33, and Lsa2517 and Lsa3018 with the same ligand.

PLG acquisition and PLA generation has been reported for several pathogens, including the spirochetes Borrelia spp. and Treponema denticola with possible implications for pathogenesis.41,49–52 PLA is a serine protease that can degrade a large spectrum of substrates, including fibrin clots, connective tissue, and components of extracellular matrices.53,54 Human PLG/PLA proteolytic activity was first described for Leptospira spp. by our group.19 Verma and others55 have shown that the protein LenA of L. interrogans is a surface receptor for human PLG. Furthermore, several PLG-binding proteins of Leptospira have been identified.8,15–18,20,40

We report Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 as novel PLG-binding proteins that are capable of generating PLA by addition of uPA-type PLG activator and show specific proteolytic activity. These three proteins of Leptospira, in addition to binding ECM and a possible role in adherence, may also help the bacteria to overcome initial physical barriers of the hosts by PLA generation. Lsa23 and Lsa36 are plasma fibronectin-interacting proteins, more specifically with the F30-kDa proteolytic fragment of fibronectin. This fragment is known to bind to heparin, and as expected, addition of increasing amounts of heparin decreased binding of Lsa36 to F30-kDa fragment, confirming that F30-kDa heparin-binding domain of fibronectin is involved in this interaction.

Pathogens have evolved strategies to escape clearance by complement, either by sequestering host-complement regulators or by down-regulating complement activation.56,57 Factor H is a host fluid-phase regulator of the alternative complement pathway, and C4b-binding protein controls the complement classical pathway by interfering with formation and regeneration of C3 convertase and acting as a cofactor to the serine proteinase factor I in the proteolytic inactivation of C4b.57,58 Filamentous haemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis, porin molecules (Por 1A and Por 1B) of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Ig-binding proteins of Streptococcus pyogenes are example of proteins binding complement regulators.59–61 Pathogenic leptospiral complement-resistant strains were found to bind factor H from human serum, and this interaction seems to be associated with their serum resistance.62 Leptospiral binding proteins to C4BP, factor H, and factor H-like have been identified in Leptospira.17,18,46,63–66 We report that Lsa23 is a novel C4BP and factor H binding protein of Leptospira, although with the ligand affinity for factor H binding protein seems to be low.

We report characterization of three leptospiral proteins selected from genome sequences of L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni annotated as hypothetical proteins and predicted to be located in the bacterial membrane. Recombinant proteins Lsa23, Lsa26, and Lsa36 are laminin- and PLG-binding proteins that might be involved in attachment and host tissue penetration. Lsa23 and Lsa36 interact with fibronectin and involve the F30-kDa heparin-binding domain. Moreover, Lsa23 can bind the complement regulators C4bp and, to a lesser extent, factor H, a feature that suggests a possible contribution in the immune evasion of leptospires. Accordingly, Lsa23 is a novel multifunctional protein that might have several tasks in leptospiral pathogenesis. To date, Lsa23 is the first described laminin-, fibronectin-, PLG-, factor H and C4bp – leptospiral-binding protein.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, and Fundacao Butantan, Brazil. Gabriela H. Siqueira and Marina V. Atzingen were supported by scholarships from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo.

Authors' addresses: Gabriela H. Siqueira, Marina V. Atzingen, Ivy J. Alves, and Ana L. T. O. Nascimento, Centro de Biotecnologia, Instituto Butantan, Avenida Vital Brazil, 1500, 05503-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, e Programa de Pós-Graduação Interunidades em Biotecnologia, Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Prof. Lineu Prestes, 1730, 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, E-mails: gabihase@usp.br, marina.atzingen@gmail.com, ivyalves@butantan.gov.br, and ana.nascimento@butantan.gov.br. Zenaide M. de Morais and Silvio A. Vasconcellos, Laboratório de Zoonoses Bacterianas do Veterinária Preventiva e Saúde Animal, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Prof. Dr. Orlando Marques de Paiva, 87, 05508-270, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, E-mails: zenaide@usp.br and savasco@usp.br.

References

- 1.Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, Levett PN, Gilman RH, Willig MR, Gotuzzo E, Vinetz JM. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:757–771. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de la Pena-Moctezuma A, Bulach DM, Adler B Genetic differences among the LPS biosynthetic loci of serovars of Leptospira interrogans and Leptospira borgpetersenii. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2001;31:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and Leptospirosis. Melbourne. Australia: MediSci Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juncker AS, Willenbrock H, Von Heijne G, Brunak S, Nielsen H, Krogh A. Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1652–1662. doi: 10.1110/ps.0303703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nascimento AL, Ko AI, Martins EA, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Ho PL, Haake DA, Verjovski-Almeida S, Hartskeerl RA, Marques MV, Oliveira MC, Menck CF, Leite LC, Carrer H, Coutinho LL, Degrave WM, Dellagostin OA, El-Dorry H, Ferro ES, Ferro MI, Furlan LR, Gamberini M, Giglioti EA, Goes-Neto A, Goldman GH, Goldman MH, Harakava R, Jeronimo SM, Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL, Kimura ET, Kuramae EE, Lemos EG, Lemos MV, Marino CL, Nunes LR, de Oliveira RC, Pereira GG, Reis MS, Schriefer A, Siqueira WJ, Sommer P, Tsai SM, Simpson AJ, Ferro JA, Camargo LE, Kitajima JP, Setubal JC, Van Sluys MA. Comparative genomics of two Leptospira interrogans serovars reveals novel insights into physiology and pathogenesis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2164–2172. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2164-2172.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nascimento AL, Verjovski-Almeida S, Van Sluys MA, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Camargo LE, Digiampietri LA, Harstkeerl RA, Ho PL, Marques MV, Oliveira MC, Setubal JC, Haake DA, Martins EA. Genome features of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:459–477. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes LG, Vieira ML, Kirchgatter K, Alves IJ, de Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Romero EC, Nascimento AL. OmpL1 is an extracellular matrix- and plasminogen-interacting protein of Leptospira spp. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3679–3692. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00474-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atzingen MV, Gomez RM, Schattner M, Pretre G, Goncales AP, de Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Lp95, a novel leptospiral protein that binds extracellular matrix components and activates e-selectin on endothelial cells. J Infect. 2009;59:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbosa AS, Abreu PA, Neves FO, Atzingen MV, Watanabe MM, Vieira ML, Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. A newly identified leptospiral adhesin mediates attachment to laminin. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6356–6364. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00460-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atzingen MV, Barbosa AS, De Brito T, Vasconcellos SA, de Morais ZM, Lima DM, Abreu PA, Nascimento AL. Lsa21, a novel leptospiral protein binding adhesive matrix molecules and present during human infection. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longhi MT, Oliveira TR, Romero EC, Goncales AP, de Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. A newly identified protein of Leptospira interrogans mediates binding to laminin. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1275–1282. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011916-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vieira ML, de Morais ZM, Goncales AP, Romero EC, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Lsa63, a newly identified surface protein of Leptospira interrogans binds laminin and collagen IV. J Infect. 2010;60:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira TR, Longhi MT, Goncales AP, de Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. LipL53, a temperature regulated protein from Leptospira interrogans that binds to extracellular matrix molecules. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira R, de Morais ZM, Goncales AP, Romero EC, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Characterization of novel OmpA-like protein of Leptospira interrogans that binds extracellular matrix molecules and plasminogen. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendes RS, Von Atzingen M, de Morais ZM, Goncales AP, Serrano SM, Asega AF, Romero EC, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. The novel leptospiral surface adhesin Lsa20 binds laminin and human plasminogen and is probably expressed during infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4657–4667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05583-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domingos RF, Vieira ML, Romero EC, Goncales AP, de Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Features of two proteins of Leptospira interrogans with potential role in host-pathogen interactions. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souza NM, Vieira ML, Alves IJ, de Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Lsa30, a novel adhesin of Leptospira interrogans binds human plasminogen and the complement regulator C4bp. Microb Pathog. 2012;53:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vieira ML, Vasconcellos SA, Goncales AP, de Morais ZM, Nascimento AL. Plasminogen acquisition and activation at the surface of Leptospira species lead to fibronectin degradation. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4092–4101. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00353-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vieira ML, Atzingen MV, Oliveira TR, Oliveira R, Andrade DM, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. In vitro identification of novel plasminogen-binding receptors of the pathogen Leptospira interrogans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner LH. Leptospirosis. 3. Maintenance, isolation and demonstration of leptospires. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1970;64:623–646. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(70)90087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu CS, Lin CJ, Hwang JK. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins for gram-negative bacteria by support vector machines based on n-peptide compositions. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1402–1406. doi: 10.1110/ps.03479604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P. SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, Bateman A. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–D251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Tasneem A, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zhang N, Bryant SH. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D205–D210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramos CR, Abreu PA, Nascimento AL, Ho PL. A high-copy T7 Escherichia coli expression vector for the production of recombinant proteins with a minimal N-terminal His-tagged fusion peptide. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1103–1109. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhandari P, Gowrishankar J. An Escherichia coli host strain useful for efficient overproduction of cloned gene products with NaCl as the inducer. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4403–4406. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4403-4406.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Louis-Jeune C, Andrade-Navarro MA, Perez-Iratxeta C. Prediction of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism using theoretically derived spectra. Proteins. 2012;80:374–381. doi: 10.1002/prot.23188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira TR, Longhi MT, de Morais ZM, Romero EC, Blanco RM, Kirchgatter K, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Evaluation of leptospiral recombinant antigens MPL17 and MPL21 for serological diagnosis of leptospirosis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1715–1722. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00214-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flannery B, Costa D, Carvalho FP, Guerreiro H, Matsunaga J, Da Silva ED, Ferreira AG, Riley LW, Reis MG, Haake DA, Ko AI. Evaluation of recombinant Leptospira antigen-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for the serodiagnosis of leptospirosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3303–3310. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3303-3310.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haake DA, Chao G, Zuerner RL, Barnett JK, Barnett D, Mazel M, Matsunaga J, Levett PN, Bolin CA. The leptospiral major outer membrane protein LipL32 is a lipoprotein expressed during mammalian infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2276-2285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamm LV, Gherardini FC, Parrish EA, Moomaw CR. Heat shock response of spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1572–1575. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1572-1575.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin YP, Lee DW, McDonough SP, Nicholson LK, Sharma Y, Chang YF. Repeated domains of Leptospira immunoglobulin-like proteins interact with elastin and tropoelastin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19380–19391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altschul SF, Wootton JC, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Morgulis A, Schaffer AA, Yu YK. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J. 2005;272:5101–5109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malmstrom J, Beck M, Schmidt A, Lange V, Deutsch EW, Aebersold R. Proteome-wide cellular protein concentrations of the human pathogen Leptospira interrogans. Nature. 2009;460:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature08184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinne M, Haake DA. A comprehensive approach to identification of surface-exposed, outer membrane-spanning proteins of Leptospira interrogans. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vieira ML, Atzingen MV, Oliveira R, Mendes RS, Domingos RF, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. Plasminogen binding proteins and plasmin generation on the surface of Leptospira spp.: the contribution to the bacteria-host interactions. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/758513. doi:10.1155/2012/758513. Epub 2012 Oct 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahteenmaki K, Kuusela P, Korhonen TK. Bacterial plasminogen activators and receptors. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:531–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seib KL, Zhao X, Rappuoli R. Developing vaccines in the era of genomics: a decade of reverse vaccinology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18((Suppl 5)):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider MC, Exley RM, Chan H, Feavers I, Kang YH, Sim RB, Tang CM. Functional significance of factor H binding to Neisseria meningitidis. J Immunol. 2006;176:7566–7575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hava DL, Camilli A. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1389–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ljungh A, Wadstrom T. Interactions of bacterial adhesins with the extracellular matrix. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;408:129–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0415-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevenson B, Choy HA, Pinne M, Rotondi ML, Miller MC, Demoll E, Kraiczy P, Cooley AE, Creamer TP, Suchard MA, Brissette CA, Verma A, Haake DA. Leptospira interrogans endostatin-like outer membrane proteins bind host fibronectin, laminin and regulators of complement. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carvalho E, Barbosa AS, Gomez RM, Cianciarullo AM, Hauk P, Abreu PA, Fiorini LC, Oliveira ML, Romero EC, Goncales AP, Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Ho PL. Leptospiral TlyC is an extracellular matrix-binding protein and does not present hemolysin activity. FEBS Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinne M, Choy HA, Haake DA. The OmpL37 surface-exposed protein is expressed by pathogenic Leptospira during infection and binds skin and vascular elastin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coleman JL, Benach JL. Use of the plasminogen activation system by microorganisms. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;134:567–576. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coleman JL, Benach JL. The generation of enzymatically active plasmin on the surface of spirochetes. Methods. 2000;21:133–141. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nordstrand A, Shamaei-Tousi A, Ny A, Bergstrom S. Delayed invasion of the kidney and brain by Borrelia crocidurae in plasminogen-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5832–5839. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5832-5839.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haile WB, Coleman JL, Benach JL. Reciprocal upregulation of urokinase plasminogen activator and its inhibitor, PAI-2, by Borrelia burgdorferi affects bacterial penetration and host-inflammatory response. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1349–1360. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ponting CP, Marshall JM, Cederholm-Williams SA. Plasminogen: a structural review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1992;3:605–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Angles-Cano E, Rouy D, Lijnen HR. Plasminogen binding by alpha 2-antiplasmin and histidine-rich glycoprotein does not inhibit plasminogen activation at the surface of fibrin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1156:34–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(92)90092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verma A, Brissette CA, Bowman AA, Shah ST, Zipfel PF, Stevenson B. Leptospiral endostatin-like protein A is a bacterial cell surface receptor for human plasminogen. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2053–2059. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01282-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindahl G, Sjobring U, Johnsson E. Human complement regulators: a major target for pathogenic microorganisms. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blom AM. Structural and functional studies of complement inhibitor C4b-binding protein. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:978–982. doi: 10.1042/bst0300978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gigli I, Fujita T, Nussenzweig V. Modulation of the classical pathway C3 convertase by plasma proteins C4 binding protein and C3b inactivator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6596–6600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berggard K, Johnsson E, Mooi FR, Lindahl G. Bordetella pertussis binds the human complement regulator C4BP: role of filamentous hemagglutinin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3638–3643. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3638-3643.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ram S, Cullinane M, Blom AM, Gulati S, McQuillen DP, Monks BG, O'Connell C, Boden R, Elkins C, Pangburn MK, Dahlback B, Rice PA. Binding of C4b-binding protein to porin: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med. 2001;193:281–295. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thern A, Stenberg L, Dahlback B, Lindahl G. Ig-binding surface proteins of Streptococcus pyogenes also bind human C4b-binding protein (C4BP), a regulatory component of the complement system. J Immunol. 1995;154:375–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meri T, Murgia R, Stefanel P, Meri S, Cinco M. Regulation of complement activation at the C3-level by serum resistant leptospires. Microb Pathog. 2005;39:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Castiblanco-Valencia MM, Fraga TR, Silva LB, Monaris D, Abreu PA, Strobel S, Jozsi M, Isaac L, Barbosa AS. Leptospiral immunoglobulin-like proteins interact with human complement regulators factor H, FHL-1, FHR-1, and C4BP. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:995–1004. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbosa AS, Monaris D, Silva LB, Morais ZM, Vasconcellos SA, Cianciarullo AM, Isaac L, Abreu PA. Functional characterization of LcpA, a surface-exposed protein of Leptospira spp. that binds the human complement regulator C4BP. Infect Immun. 2012;78:3207–3216. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00279-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verma A, Hellwage J, Artiushin S, Zipfel PF, Kraiczy P, Timoney JF, Stevenson B. LfhA, a novel factor H-binding protein of Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2659–2666. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2659-2666.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choy HA. Multiple activities of LigB potentiate virulence of Leptospira interrogans: inhibition of alternative and classical pathways of complement. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]