Abstract

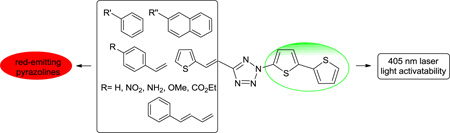

The design and synthesis of a new class of laser light activatable tetrazoles with extended π systems is reported. Upon 405 nm laser light irradiation, these bithiophene-substituted tetrazoles underwent extremely fast 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions with dimethyl fumarate with second-order rate constants approaching 4000 M−1 s−1. The resulting pyrazoline cycloadducts exhibited solvent-dependent red fluorescence, making these tetrazoles potentially useful as fluorogenic probes for detecting alkenes in vivo.

Biomolecular imaging with fluorophores allows real-time monitoring of cellular processes with high spatial and temporal resolution. Compared with fluorescent proteins, chemical fluorescent probes are less likely to perturb the biological process under study because of their small sizes and tunable photophysical properties.1 To minimize the interference caused by autofluorescence, environment-sensitive fluorescent probes with emissions in the red or near-infrared region are highly desirable for diverse applications in living systems,2 including detecting protein localization,3 probing protein electrostatics,4 and studying protein conformations.5

Recently, we reported the in situ formation of pyrazoline fluorphores for labeling proteins in living cells via a photoinduced tetrazole–alkene cycloaddition reaction (‘photoclick’ chemistry).6 Compared with direct fluorophore attachment, the advantages of our photoclick chemistry approach include: (i) the ability to form a fluorophore at any desired location within a protein target through the use of amber codon suppression technique; (ii) the fluorogenic nature of the reaction allows fluorescent imaging without the washing step; (iii) the necessary photoinduction step offers a spatiotemporal control over the fluorophore generation. While we have endeavored to tune photoactivation wavelength to the long-wavelength region,7 including 405 nm laser light,8 the emissions of the pyrazoline fluorophores are still restricted to cyan-to-green colors.9 Therefore, the pyrazolines with the red to infrared fluorescence are highly desirable. To this end, here we report the design and synthesis of N2-bithiophene-substituted tetrazoles that can be activated by a 405 nm laser light and produce the red-emitting pyrazoline fluorophores upon fast cycloaddition reactions with dimethyl fumarate. Futhermore, we found that the in situ formed pyrazoline fluorophores showed solvent-dependent fluorescence, which may make them useful to probe polarity changes in biological systems.

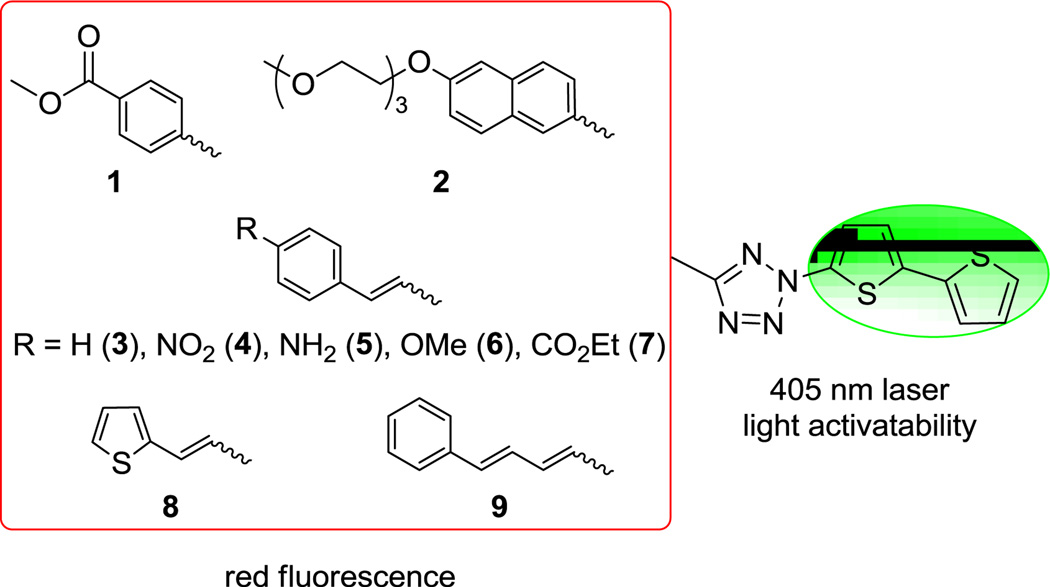

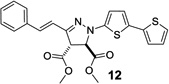

In designing tetrazoles that yield red fluorescent pyrazoline cycloadducts, we considered the following recent findings: (i) the subtitution of the bithiophene moiety at the N2-position of tetrazole gave rise to not only 405 nm photoactivatability8 but also excellent cycloaddition reactivity;10 and (ii) extended π-conjugation, particularly at the C5-position of tetrazole modulates the fluorescence of the resulting pyrazolines. We hypothesized that the tetrazoles with N2-bithiophene substituent and an extended π system at C5-position would generate red fluorescent pyrazoline cycloadducts upon cycloaddition with a suitable dipolarophile while at the same time retain 405 nm photoreactivity and fast cycloaddition reaction kinetics. Accordingly, we designed tetrazoles 1-9 incorporating these two features (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tetrazole structures with bisthiophene as a trigger for 405 nm photoreactivity.

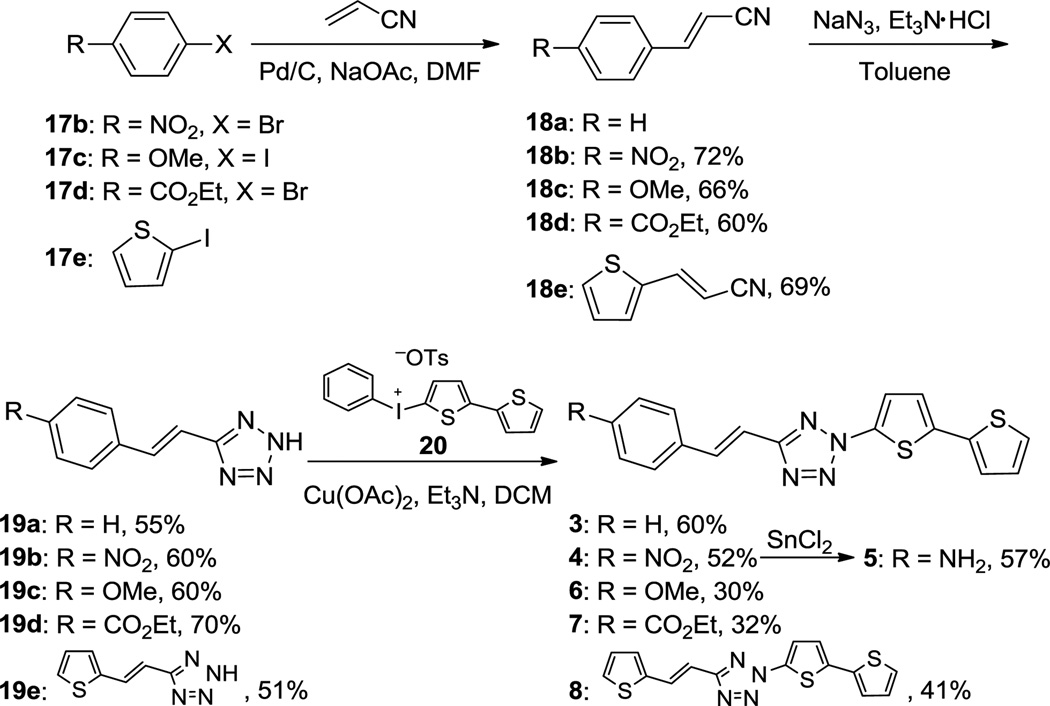

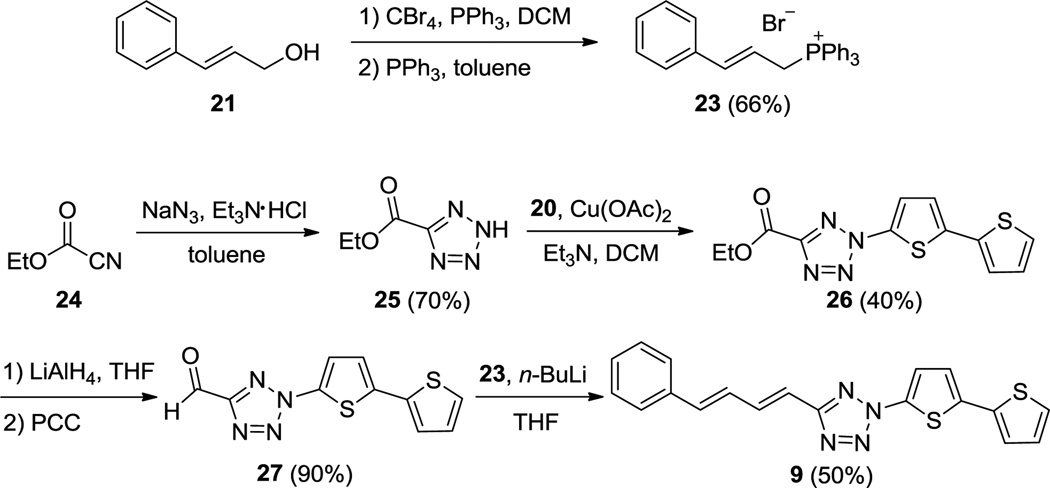

Diaryltetrazoles 1 and 2 were synthesized using the cross-coupling method we reported recently8 (Scheme S1). Separately, a convergent route was developed for the synthesis of styrenylaryltetrazoles 3–8 (Scheme 1). In brief, the substituted (E)-arylacrylonitriles 18b–e were prepared through the Heck-type cross-coupling between acrylonitrile and the various aryl halides 17b–e with 60-72% yields. The nitrile was then converted to 2H-tetrazole in 51–70% yields by treating the arylacrylonitriles with NaN3 in the presence of triethylammonium chloride in toluene. The tetrazoles 3-4 and 6–8 were obtained through the CuII-catalyzed cross-coupling between tetrazoles 19a–e and phenyl(bithio phen-2-yl)iodonium salt 20 with modest yields. The amine-substituted vinylaryltetrazole 5 was obtained in 57% yield by treating tetrazole 4 with SnCl2 (Scheme 1).

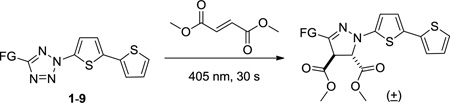

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of tetrazole 3–8

The trans, trans-phenylbutadiene-substituted tetrazole 9 was constructed by the Wittig reaction according to Scheme 2. Briefly, cinnamyl alcohol 21 was converted to the corresponding phosphonium bromide 23 in 66% yield through successive treatment of CBr4 and PPh3. The cognate aldehyde 27 was synthesized through a four-step procedure: (i) ethyl carbonocyanidate was reacted with NaN3 to give tetrazole 25 in 70% yield; (ii) tetrazole 25 was treated with phenyl(bithiophen-2-yl)iodonium salt 20 in the presence of Cu(OAc)2 to afford tetrazole 26 in 40% yield; (iii) reduction of 26 by LiAlH4 and (iv) oxidation with PCC generated aldehyde 27 in 90% yield over two steps. Finally, Wittig reaction was carried out by treating phosphonium bromide 23 with n-BuLi followed by the addition of 27 to give 2-bithiophen-2-yl)-5-trans, trans-4-phenylbuta-1,3-dienyltetrazole 9 in 50% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of tetrazole 9

With tetrazoles 1–9 in hand, their UV-Vis properties were measured and the data are collected in Table 1. The maximum absorption wavelength ranges from 352 nm to 364 nm. Tetrazoles with the electron-donating groups (5 and 6) provide greater molar absorption coeffcients than those with the electron-withdrawing groups (4 and 7). Subsequently, we examined the photoreactivities of the tetrazoles toward dimethyl fumarate, a symmetrical electron-deficient dipolarophile we used previously,8,12 in PBS/ACN (1:1, v/v; PBS = phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4) with irradiation by a diode laser (405 nm, 24 mW).13 We found that tetrazoles 2, 3, 7, and 8 gave clean conversions to the pyrazoline cycloadducts (Table 1) while tetrazoles 6 and 9 showed ≥90% yields along with small amounts of side products based on HPLC traces (Figure S2). Tetrazole 1 gave only 58% conversion with with the rest being the starting materials. Interestingly, tetrazoles 4 and 5 showed no reactivity despite their strong absorption at 405 nm (Figure S1). The lack of photoreacitivity for the NO2-containing tetrazoles, but not the ester-containing tetrazoles,7a was also observed in our previous studies.11 On the other hand, tetrazole 5 was found to be weakly fluorescent, emitting the incident light as the fluorescence rather than breaking up the tetrazole ring.

Table 1.

UV-Vis absorption properties of tetrazoles 1–9 and characterization of their reactivities in the 405 nm laser light induced cycloaddition reaction a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tet | λmax (nm) |

εmax (M−1 cm−1) |

pyrazoline | yield (%)b |

k2 (M−1 s−1)c |

| 1 | 352 | 18,600 |  |

58 | 220 ± 30 |

| 2 | 356 | 26,200 |  |

98 | 1,430 ±73 |

| 3 | 354 | 27,700 |  |

97 | 1,450 ± 150 |

| 4 | 362 | 22,400 |  |

NDd | / |

| 5 | 364 | 31,100 |  |

NDd | / |

| 6 | 356 | 32,400 |  |

92 | 3,870 ± 260 |

| 7 | 356 | 22,400 |  |

95 | 350 ± 40 |

| 8 | 360 | 26,400 |  |

95 | 3,600 ± 570 |

| 9 | 358 | 46,500 |  |

90 | 3,960 ± 172 |

For UV-Vis measurement, tetrazoles were dissolved in PBS/ACN (1:1, v/v) to obtain concentrations of 25 μM. For cycloaddition reactions, a solution of 20 μM tetrazole and 1 mM dimethyl fumarate in 1 mL PBS/ACN (1:1) in a quartz test tube was photoirradiated with 405 laser for 30 s.

Yields were determined by comparing the desired pyrazole peak area in the HPLC trace to that of a pyrazoline control with known concentration. See Figure S2 in the Supporting Information for details.

Second-order rate constant of the cycloaddition; see Figure S3 in the Supporting Information for details. d The desired pyrazoline product was not detected; however, the tetrazole was found stable under the photoirradiation condition.

To quantify tetrazole reactivity, we performed kinetic analyses by following the cycloaddition reactions of tetrazoles with dimethyl fumarate in quartz tubes under 405 nm laser irradiation with HPLC. The second-order rate constants, k2, were determined (Figure S3), and the data are collected in Table 1. To our delight, tetrazoles 6, 8 and 9 showed extremely fast kinetics with k2 values approaching 4000 M−1 s−1, more than threefold faster than pure oligothiophene-based tetrazoles.8 This is probably due to the HOMO-lifting effect (increases in the nitrile imine HOMO energies)10 endowed by attachment of the extended electron-rich π system to the in situ generated nitrile imine. Meanwhile, when the electron-withdrawing ester group was present, greater than 10-fold reduction in kinetic constant was observed (k2 = 220 and 350 M−1 s−1 for tetrazoles 1 and 7, respectively). In general, styrenylaryltetrazoles showed faster reaction kinetics than diaryltetrazoles (compare 1 to 7 and 2 to 6). Remarkably, the potential intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions14 among styrenylaryltetrazoles 3-8 and phenylbutadienylaryltetrazole 9 were not observed, presumably due to geometric constraint posed by the trans-alkenes in these tetrazoles.

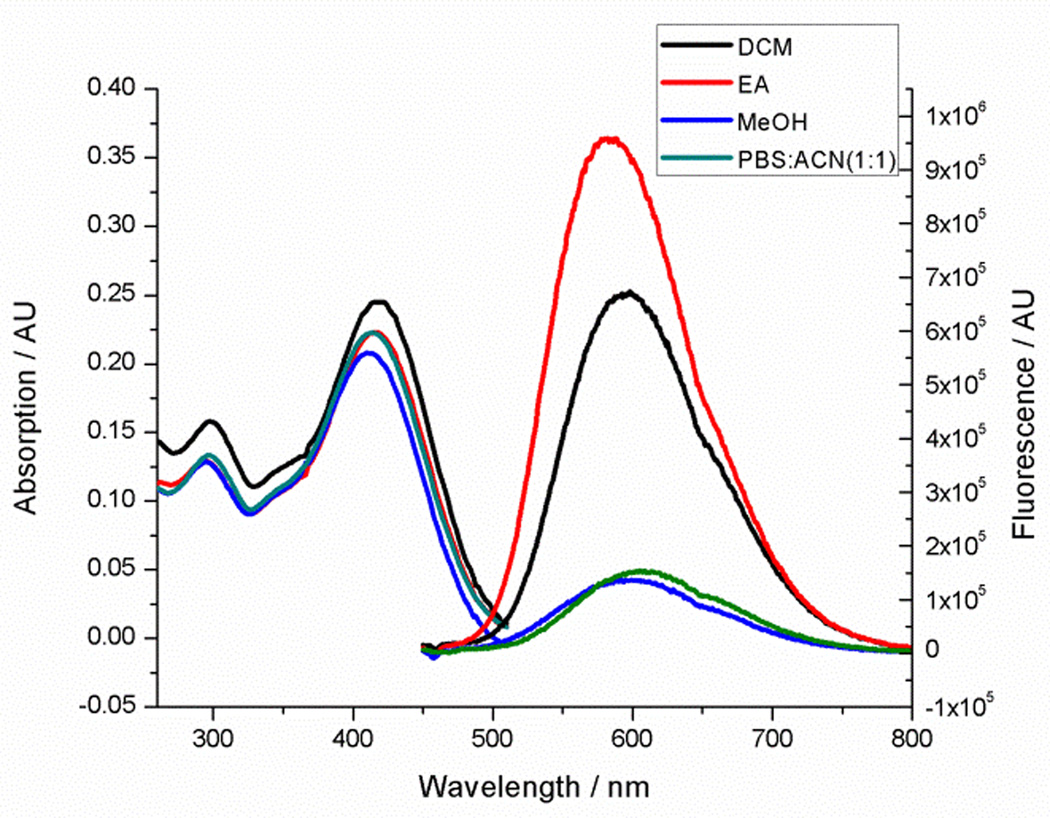

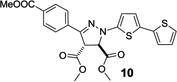

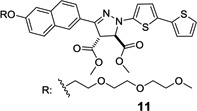

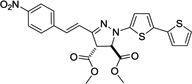

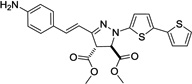

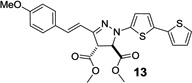

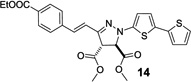

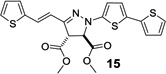

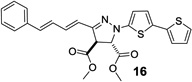

Next, the pyrazoline cycloadducts 10–16 were isolated and their photophysical properties are collected in Table 2. All pyrazoline cycloadducts showed bathochromic shifts in their absorption and emission maxima compared to diaryltetrazoles15, accompanied by large Stokes shifts (6490–6860 cm−1; Table 2). To our delight, all pyrazoline cycloadducts except 11 showed red fluorescence in PBS/ACN (1:1, v/v), and pyrazoline 14 even reached near-infrared region with λem of 644 nm. However, the quantum yields of the pyrazoline fluorophores were rather low (0.2–1.5%), which can be attributed to their flexible structures and thus their strong tendency of nonradiative decay. Another observation was that the emission maxima of these pyrazolines depend critically on solvent polarity with significant hypsochromic shifts (12–34 nm) going from polar solvents to nonpolar ones, while the absorption spectra showed little change. As an illustration, pyrazoline 12 gave an emission maximum of 612 nm in polar PBS/ACN (1:1, v/v) solvent, but 582 nm in nonpolar EtOAc along with a concurrent increase in fluorescence intensity by more than 6-fold (Figure 2). This fluorescence intensity “turn-on” increased to 30-fold when organic co-solvent ACN in PBS/ACN decreased to 20% (Figure S4); suggesting that these red-emitting pyrazoline fluorophores may serve as environment-sensitive probes to detect polarity change in protein structures.3–5

Table 2.

UV-Vis absorption and fluorescence properties of pyrazolines 10–16 a

| λmax (nm) | λem (nm)b | stokes shift (cm−1)c |

Фf (%)d |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pyrazoline | EtOAc | PBS/ACN | EtOAc | PBS/ACN | ||

| 10 | 425 | 425 | 596 | 630 | 6750 | 0.3 |

| 11 | 402 | 402 | 553 | 575 | 6790 | 1.5 |

| 12 | 416 | 416 | 582 | 612 | 6860 | 0.4 |

| 13 | 418 | 418 | 574 | 600 | 6500 | 0.4 |

| 14 | 437 | 437 | 610 | 644 | 6490 | 0.2 |

| 15 | 424 | 424 | 595 | 615 | 6780 | 0.3 |

| 16 | 435 | 432 | 608 | 620 | 6540 | 0.2 |

Pyrazolines were dissolved in either EtOAc or PBS/ACN (1:1, v/v) to obtain concentrations of 10 μM.

λex = 405 nm.

Based on the values measured in EtOAc.

Fluorescence quantum yields were determined in EtOAc using DAPI dye as a reference.

Figure 2.

UV-Vis absorption (left) and fluorescence spectra (right) of pyrazoline 12 measured at 10 μM in the various solvents. For fluorescence measurement, λex = 405 nm.

In summary, we have designed and synthesized a series of biaryl and styrenylaryl tetrazoles containing both a 405 nm photoactivatable bithiophene moiety and an extended π system. The majority of these new tetrazoles participate in the laser-triggered photoclick reaction with dimethyl fumarate, giving rise to the red fluorescent pyrazoline cycloadducts with the fastest kinetics reported for the photoclick chemistry (k2 up to 3,960 M−1 s−1). Because the pyrazoline cycloadducts show environment-dependent “turn-on” fluorescence, these new tetrazoles should offer a useful tool to study protein electrostatics and protein conformations involving changes in solvent accessibility and/or polarity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (GM 85092) for financial support. P.A. is a visiting graduate student from Lanzhou University sponsored by China Scholarship Council.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supplemental figures, experimental procedure and characterization of all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Lavis LD, Raines RT. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:142. doi: 10.1021/cb700248m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Egawa T, Hirabayashi K, Koide Y, Kobayashi C, Takahashi N, Mineno T, Terai T, Ueno T, Komatsu T, Ikegaya Y, Matsuki N, Nagano T, Hanaoka K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:3874. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun W, Fan J, Hu C, Cao J, Zhang H, Xiong X, Wang J, Cui S, Sun S, Peng X. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:3890. doi: 10.1039/c3cc41244j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yuan L, Lin W, Yang Y, Chen H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1200. doi: 10.1021/ja209292b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lukinavičius G, Umezawa K, Olivier N, Honigmann N, Yang G, Plass T, Mueller V, Reymond L, Corrĕa IR, Jr, Luo Z, Schultz C, Lemke EA, Heppenstall P, Eggeling C, Manley S, Johnsson K. Nature Chem. 2013;5:132. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhuang Y-D, Chiang P-Y, Wang C-W, Tan K-T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8124. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen BE, McAnaney TB, Park ES, Jan YN, Boxer SG, Jan LT. Science. 2002;296:1700. doi: 10.1126/science.1069346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen BE, Pralle A, Yao X, Swaminath G, Gandhi CS, Jan YN, Kobilka BK, Isacoff EY, Jan LY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409469102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Song W, Wang Y, Qu J, Madden MM, Lin Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2832. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Song W, Wang Y, Qu J, Lin Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9654. doi: 10.1021/ja803598e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lim RK, Lin Q. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:828. doi: 10.1021/ar200021p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Wang Y, Hu WJ, Song W, Lim RK, Lin Q. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3725. doi: 10.1021/ol801350r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu Z, Ho LY, Wang Z, Lin Q. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:5033. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An P, Yu Z, Lin Q. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:9920. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45752d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Song W, Wang Y, Yu Z, Vera CI, Qu J, Lin Q. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:875. doi: 10.1021/cb100193h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu Z, Pan Y, Wang Z, Wang J, Lin Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:10600. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Song W, Hu WJ, Lin Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5530. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Vera CI, Lin Q. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4155. doi: 10.1021/ol7017328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Wang J, Zhang W, Song W, Wang Y, Yu Z, Li J, Wu M, Wang L, Zang J, Lin Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14812. doi: 10.1021/ja104350y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lim RK, Lin Q. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:7993. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02863k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Light intensity value was recorded by placing a FieldMaster GS energy analyzer equipped with LM-10 HTD power meter sensor in the light path of the laser beam.

- 14.Yu Z, Ho LY, Lin Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11912. doi: 10.1021/ja204758c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Hu WJ, Song W, Lim RKV, Lin Q. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3725. doi: 10.1021/ol801350r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.