Abstract

Background

Psychological effects of mastectomy for women with breast cancer have driven treatments that optimize cosmesis while strictly adhering to oncologic principles. Although skin-sparing mastectomy is oncologically safe, questions remain regarding the use of nipple–areola complex (NAC)-sparing mastectomy (NSM). We prospectively evaluated NSM for patients undergoing mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer or risk reduction.

Methods

We enrolled 33 early-stage breast cancer and high-risk patient; 54 NSMs were performed. NAC viability and surgical complications were evaluated. Intraoperative and postoperative pathologic assessments of the NAC base tissue were performed. NAC sensory, cosmetic and quality of life (QOL) outcomes were also assessed.

Results

Twenty-one bilateral and 12 unilateral NSMs were performed in 33 patients, 37 (68.5%) for prophylaxis and 17 (31.5%) for malignancy. Mean age was 45.4 years. Complications occurred in 16 NACs (29.6%) and 6 skin flaps (11.1%). Operative intervention for necrosis resulted in 4 NAC removals (7.4%). Two (11.8%) of the 17 breasts with cancer had ductal carcinoma-in-situ at the NAC margin, necessitating removal at mastectomy. All evaluable patients had nipple erection at 6 and 12 months postoperatively. Cosmetic outcome, evaluated by two plastic surgeons, was acceptable in 73.0% of breasts and 55.8% of NACs, but lateral displacement occurred in most cases. QOL assessment indicated patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

NSM is technically feasible in select patients, with a low risk for NAC removal resulting from necrosis or intraoperative detection of cancer, and preserves sensation and QOL. Thorough pathologic assessment of the NAC base is critical to ensure disease eradication.

The surgical treatment options available to breast cancer patients have progressed from radical mastectomy, which provided a dramatic decrease in local recurrence and improved survival when it was developed, to the modified radical or total mastectomy. In 1977, the NSABP B-04 trial demonstrated that total mastectomy provided locoregional control with less morbidity than observed with radical mastectomy. Unfortunately, total mastectomy was still disfiguring to women, and clinicians began to explore breast reconstruction and improved mastectomy techniques.1 Toth and Lappert were the first to introduce the skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM), which provided oncologic outcomes similar to total mastectomy by removing all breast tissue but maintained the breast skin envelope to accommodate immediate reconstruction of the breast at the same time as mastectomy.2

Despite these improvements in surgical techniques, there remains a psychosocial impact of removing the nipple–areola complex (NAC), leading some to explore the technical and oncologic feasibility of the NAC-sparing mastectomy (NSM). Unlike the well-established forms of mastectomies for breast cancer treatment, the NSM technique is widely variable. These variations can have a marked impact on associated complications and local recurrence rates as a result of residual ductal tissue under the NAC and skin flaps. In addition, selection criteria for breast cancer patients who are most appropriate for treatment with NSM with a low risk of NAC tumor involvement have not been established. We initiated a prospective pilot study to assess the feasibility and oncologic safety of NSM. We assessed NAC and skin flap complications and local recurrence. In addition, we measured NAC sensation, cosmetic outcomes, and quality of life for patients who underwent NSM.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

Patients desiring prophylactic mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and those with stage 0, I, or II breast cancer who were candidates for and desiring SSM with immediate reconstruction were recruited for this prospective trial. The study was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board. Patients with cancer were eligible for participation if the tumor was at least 2.5 cm from the border of the NAC on preoperative imaging and/or clinical exam. Patients with cancer were excluded if there were signs indicating nipple involvement, such as induration, retraction, fixation, ulceration, pathologic nipple discharge, or Paget’s disease. Patients were not eligible if they had prior breast surgery with periareolar incisions, a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2, were active smokers, collagen vascular disease, or prior chest wall irradiation less than 12 months from the planned surgery.

Operative Technique

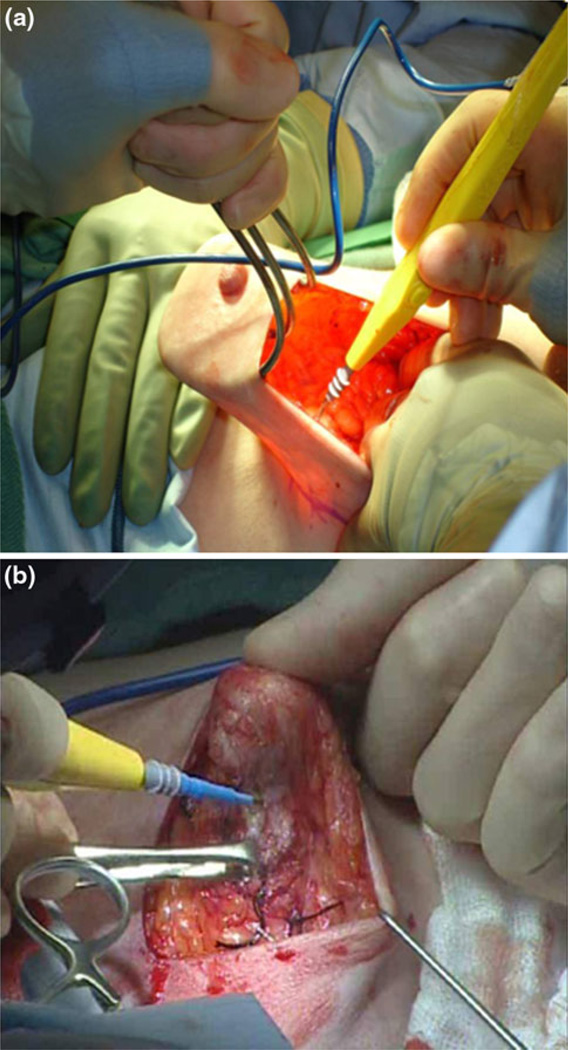

Patients underwent SSM with preservation of the NAC through an incision made at the discretion of the surgical oncologist and plastic surgeon. An incision made in the upper outer quadrant or the lateral aspect of the breast was recorded as a “lateral” incision. Incisions made in any other location were recorded as “other.” Skin flaps were raised in a subdermal plane similar to that for an SSM by using electrocautery or tumescence solution and sharp dissection, per the surgeon’s preference (Fig. 1a). Dissection under the NAC was performed by carefully dissecting the breast parenchyma from the deep dermal layer under the NAC (Fig. 1b). The breast specimen immediately underlying the NAC was marked for orientation with four surgical clips or sutures placed on the circumference of the areolar margin at the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions and a fifth marking clip or suture immediately underlying the nipple. These areas were sampled by the pathologist via intraoperative frozen section. The NAC was resected at the time of operation if malignant cells were identified on frozen section. NAC excision was also performed if there was suspicion of vascular compromise intraoperatively. Axillary staging was performed at the time of initial operation if indicated by cancer stage and established treatment guidelines. Patients underwent immediate reconstruction with autologous tissue, expanders/implants, or a combination of modalities per the plastic surgeon’s discretion. Reconstructive options differed based upon body habitus, desired size of reconstructed breast, and state of health.

FIG. 1.

NSM dissection of skin flaps and NAC base

Pathologic Assessment of the NAC Base

The breast tissue under the NAC was subjected to additional sectioning for pathologic assessment. The same five areas assessed by frozen section were sectioned perpendicularly for permanent histologic analysis. The entire breast was then evaluated per institutional standards. Upon review of final pathologic findings for the breast specimen, a second operative procedure was performed if the breast tissue underlying the NAC was found to contain malignancy or if the tumor-to-NAC distance (TND) was within 2.5 cm.

Cosmetic Assessment and Quality-of-Life Measures

Cosmetic outcomes were assessed by two plastic surgeons from patient photographs. NAC sensory analysis was performed preoperatively for baseline assessment and postoperatively at 6 and 12 months. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast (FACT B) quality-of-life evaluations were performed upon completion of NSM.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Means, standard deviations, and ranges were used to summarize continuous variables, while categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages. An independent sample t-test was used to compare means between groups of interest. A χ2 test was used to compare proportions between groups. Logistic regression was used to explore the association between patient characteristics and clinical complications. Odds ratio estimates with 95% confidence intervals were used to quantify the strength of association between characteristics. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed by SAS software, version 9.1.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between October 2007 and March 2009, 33 patients who met study criteria were registered. Twenty-one (63.6%) patients underwent bilateral and 12 (36.4%) underwent unilateral mastectomy, for a total of 54 NSM cases. Thirty-seven NSMs were performed for risk reduction and 17 for treatment of documented malignancy. The mean age of patients was 45.4 years (range 27–66 years) and the mean BMI was 24.8 kg/m2(range 19.7–34.1 kg/m2). Genetic testing was performed on 10 (30.3%) patients, of whom 5 (15.1%) had mutations in BRCA1, 2 (6.1%) had mutations in BRCA2, and 3 (9.1%) were negative for BRCA mutations. Twenty-five patients (75.8%) had no history of tobacco use, while 8 (24.2%) had a recent or past history of tobacco use. The NSM was performed through a lateral incision in 43 (79.6%) cases, while only 11 (20.4%) cases had incisions in other locations. The median follow-up time from surgery was 15.0 months (range 1–29 months). Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Of the 17 patients with a breast cancer diagnosis, 4 (23.5%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 4 (23.5%) received adjuvant chemotherapy, and 7 (41.2%) received adjuvant endocrine therapy. The remaining 2 patients did not receive systemic therapy. No patients received post-mastectomy radiation. None of the patients developed a local recurrence during the follow-up period; however, 1 patient with triple-receptor-negative disease was diagnosed with lung metastasis 14 months after surgery.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years (n = 33) | |

| Mean | 45.4 |

| Range | 27–66 |

| BMI (kg/m2)(n = 33) | |

| Mean | 24.8 |

| Range | 19.7–34.1 |

| NSM performed (n = 33) | |

| Unilateral | 12 (36.4%) |

| Bilateral | 21 (63.6%) |

| Reason for NSM (n = 54) | |

| Prophylactic | 37 (68.5%) |

| Malignancy | 17 (31.5%) |

| Genetic testing (n = 33) | |

| BRCA1 positive | 5 (15.1%) |

| BRCA2 positive | 2 (6.1%) |

| BRCA negative | 3 (9.1%) |

| Not performed | 23 (69.7%) |

| Tobacco use (n = 33) | |

| No | 25 (75.8%) |

| Yes | 8 (24.2%) |

| Follow-up, mo (n = 33) | |

| Median | 15.0 |

| Range | 1–29 |

Pathologic Findings

Clinical and pathologic staging of our cohort are seen in Table 2. Of the 37 cases in which NSMs were performed for risk reduction, 1 case had occult disease on final pathologic evaluation. The rates of preoperative diagnosis and postoperative diagnosis of in situ carcinoma were similar (41.2% vs. 44.4%). However, while only 3 (17.6%) breasts had a clinical diagnosis of T1 disease, 6 (33.3%) breasts were determined to have a pathologic stage of T1 on final analysis. Fewer patients proved to have T2 disease on final pathologic examination than had preoperative clinical stage T2 disease (22.2% vs. 41.2%, respectively). Two breasts had associated nodal metastasis, 1 (5.6%) with pN0(i +) disease who did not undergo any further axillary treatment and 1 (5.6%) with pN1a disease who underwent completion axillary lymph node dissection; no additional positive nodes were found on final examination.

TABLE 2.

Tumor staging and pathologic characteristics

| Stage or characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical T stage (n = 17) | |

| Tis | 7 (41.2%) |

| T1 | 3 (17.6%) |

| T2 | 7 (41.2%) |

| Clinical N stage (n = 17) | |

| N0 | 17 (100%) |

| Overall clinical stage (n = 17) | |

| 0 | 7 (41.2%) |

| I | 3 (17.6%) |

| IIA | 7 (41.2%) |

| Pathologic T stage (n = 18)a | |

| Tis | 8 (44.4%) |

| T1 | 6 (33.3%) |

| T2 | 4 (22.2%) |

| Pathologic N stage (n = 18)a | |

| Nx | 1 (5.6%) |

| N0 | 15 (83.3%) |

| N0(i +) | 1 (5.6%) |

| N1a | 1 (5.6%) |

| Overall pathologic stage (n = 18)a | |

| 0 | 8 (44.4%) |

| I | 5 (27.8%) |

| IIA | 5 (27.8%) |

| Histologic type (n = 17) | |

| DCIS | 6 (35.3%) |

| ILC | 1 (5.9%) |

| IDC | 4 (23.5%) |

| IDC and DCIS | 6 (35.3%) |

| Hormone status (n = 17) | |

| ER +/PR + or PR− | 14 (82.4%) |

| ER −/PR + or PR− | 3 (17.6%) |

| HER2 status (n = 17) | |

| HER2+ | 2 (11.8%) |

| HER2− | 11 (64.7%) |

| HER2 unknown | 4 (23.5%) |

| Tumor-to-NAC distance (cm) | |

| Mean (range) | 6 (3–9) |

Includes one case of prophylactic NSM in which occult disease was found

Six of the 17 patients treated for malignancy had ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), 1 had invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), 4 had invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), and 6 had both IDC and DCIS. The majority of patients had estrogen-positive, progesterone-positive, and HER2-negative tumors (Table 2). Five of the 37 NSMs performed for risk reduction had notable pathologic findings: 1 (2.7%) with DCIS, 2 (5.4%) with lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), 1 (2.7%) with atypical ductal hyperplasia, and 1 (2.7%) with atypical lobular hyperplasia.

The mean TND was 6 cm (range 3–9 cm). Only 2 (3.7%) breasts had NAC involvement with DCIS. NAC involvement was identified by intraoperative pathologic analysis and confirmed on final pathologic analysis. The NAC was excised at the time of surgery in both cases. One NAC had LCIS at the base that also developed necrosis requiring excision at a second surgery. The remaining specimens had benign findings on final pathologic assessment.

Complications

Complications were evaluated for both the mastectomy skin flaps and the NAC (Table 3). Seromas were not considered a complication for the purposes of this study because of the potential for seroma formation with any breast procedure. Only 6 (11.1%) mastectomy flap complications were observed; 5 (9.3%) breasts had some necrosis, and 1 (1.8%) had partial dehiscence of the incision. One patient was treated for cellulitis; however, she also developed skin necrosis, and therefore, it was categorized as a necrosis complication. A total of 2 (3.7%) areolas and 14 (26.0%) nipples developed complications. There were no cases of total eschar formation of the areola, and only 2 (3.7%) cases had partial eschar formation of the areola. There were 3 (5.6%) cases of total eschar formation of the nipple and 11 (20.4%) cases of partial eschar formation of the nipple. Five NACs were excised in a second surgical procedure for reasons other than malignancy. Of these, 4 (7.4%) were excised for necrosis and 1 (1.9%) to improve symmetry per the recommendation of the plastic surgeon. The remaining 11 (20.4%) NACs with complications were successfully treated with conservative management. When complications were stratified by whether surgery was performed for malignancy versus risk reduction, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of skin flap or NAC complications (P = 0.300 and 0.506, respectively). Univariate analysis was performed to assess the association between patient characteristics and surgical complications. Although unilateral versus bilateral procedures, obesity, and tobacco history had no statistical association with complications, there was a trend toward significance in patients with older age (≥40 years; OR 0.21, P = 0.059). This trend was also seen on multivariate analysis (OR 0.18, P = 0.060).

TABLE 3.

Complications

| Complication | n (%) (N = 54) |

|---|---|

| Flap/incision | |

| Partial dehiscence | 1 (1.9) |

| Total dehiscence | 0 (0.0) |

| Wound infection | 0 (0.0) |

| Flap necrosis | 5 (9.3) |

| Flap cellulitis | 0 (0.0) |

| No complications | 48 (88.9) |

| NAC | |

| Partial eschar nipple | 11 (20.4) |

| Total eschar nipple | 3 (5.6) |

| Partial eschar areola | 2 (3.7) |

| Total eschar areola | 0 (0.0) |

| No complications | 36 (66.7) |

| Not applicable | 2 (3.7) |

| NAC excised for complication | |

| No | 50 (92.6) |

| Yes | 4 (7.4) |

Cosmetic Outcomes

Cosmetic outcomes were evaluated at 6 months independently by two plastic surgeons (Table 4). Criteria for optimal cosmesis included position of the breast and of the NAC (up/down and medial/lateral), defects of the breast and NAC, and overall appearance of the breast and NAC. Twenty-six breasts were available for evaluation. Only 25% of both breasts and NACs were judged perfect/normal/ideal in up/down position. Interestingly, 50.0% of breasts and 67.4% of NACs were laterally displaced. This is of particular interest because the majority (79.6%) of breast incisions were lateral. Defects in the breast were not visible or barely noticeable in 42.3% of breasts. In contrast, 80.8% of NACs had no or barely visible defects. The overall appearance of the breast was acceptable in 73.1%, poor in 13.5%, and unacceptable in 13.5%. Furthermore, the overall appearance of the NAC was acceptable in 55.8%, poor in 28.8%, and unacceptable in 15.4%.

TABLE 4.

Cosmetic outcomes in 26 patients

| Cosmetic item | % |

|---|---|

| Position of breast (up/down) | |

| Somewhat or moderately far inferiorly | 44.2 |

| Perfect/normal/ideal | 25.0 |

| Somewhat or moderately far superiorly | 30.8 |

| Position of breast (side/side) | |

| Somewhat or moderately far laterally | 50.0 |

| Perfect/normal/ideal | 42.3 |

| Somewhat or moderately far medially | 7.6 |

| Position of NAC (up/down) | |

| Extremely far inferiorly | 5.8 |

| Somewhat or moderately far inferiorly | 40.3 |

| Perfect/normal/ideal | 25.0 |

| Somewhat or moderately far superiorly | 23.1 |

| Extremely far superiorly | 5.8 |

| Position of NAC (side/side) | |

| Extremely far laterally | 5.8 |

| Somewhat or moderately far laterally | 61.6 |

| Perfect/normal/ideal | 30.8 |

| Somewhat or moderately far medially | 1.9 |

| Extremely far superiorly | 0.0 |

| Defects of breast | |

| No visible defects | 5.8 |

| Barely noticeable defects | 36.5 |

| Moderately visible defects | 32.7 |

| Very visible defects | 7.7 |

| Multiple, very visible defects | 17.3 |

| Defects of NAC | |

| No visible defects | 42.3 |

| Barely noticeable defects | 38.5 |

| Moderately visible defects | 1.9 |

| Very visible defects | 1.9 |

| Multiple, very visible defects | 15.4 |

| Overall appearance of breast | |

| Excellent | 7.7 |

| Very good | 26.9 |

| Good | 38.5 |

| Poor | 13.5 |

| Unacceptable | 13.5 |

| Overall appearance of NAC | |

| Excellent | 7.7 |

| Very good | 15.4 |

| Good | 32.7 |

| Poor | 28.8 |

| Unacceptable | 15.4 |

Sensory Outcomes

Sensation was evaluated by the time to erection of the nipple. The preoperative measurement was available for 36 breasts, with a median time to erection of 9.5 s (range 1–20 s). All 22 patients evaluated at 6 months had erection of the nipple present upon stimulation. The median time to erection was 25 s (range 7–95 s). Erection was also present in all 11 evaluable breasts at 12 months, with a median time of 23 s (range 9–49 s).

Quality-of-Life Outcomes

FACT B quality-of-life assessments were available for 16 of the 33 patients at the completion of the NSM. Emphasis for the purposes of this study was placed on evaluating body image and preservation of a feeling of womanhood. The majority (58.8%) of patients were “not at all” self-conscious about their dress. Most patients also felt sexually attractive, with 29.4% feeling “somewhat,” 35.2% feeling “quite a bit,” and 11.8% feeling ”very much” in response to this body image assessment. Finally, 41.2% of patients felt “very much” like a woman and 47.1% felt “quite a bit” like a woman after undergoing NSM.

DISCUSSION

SSM has been an important advancement, providing breast cancer patients low local recurrence rates similar to total mastectomy while offering improved cosmetic outcomes with immediate reconstruction.3–5 To offer a more natural NAC appearance with the potential for retained sensation, NAC projection, and original breast contour, interest in the feasibility of NSM has been elevated to provide an overall improvement in the psychosocial and cosmetic outcome associated with breast cancer treatment. Our prospective study demonstrates that NSM is technically feasible and provides good results in terms of oncologic, cosmetic, sensory, and patient QOL outcomes.

Retrospective studies of breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy have demonstrated the potential of NAC involvement in 5–7% of cases. 6,7 Several groups have compared outcomes in patients undergoing SSM and NSM and shown low local recurrence rates.8–10 The need for appropriate patient selection criteria, especially tumor size, has been stressed, and TND has been consistently correlated with disease in the NAC.5,7,11–13 As in SSM, the oncologic technique used to create the skin flaps as well as dissect the breast parenchyma from the NAC is critical to maintain low local recurrence rates. Stolier et al. describe and emphasize an NSM technique similar to what we have illustrated in this study, while others have described techniques that require irradiation to achieve acceptable local-regional control.14–16 Although our study had a limited follow-up time, we did not identify any local recurrences. Low local-regional recurrence rates have been supported by several other studies with longer follow-up periods.8,17,18

Another important component of the NSM is the pathologic evaluation of the tissue removed directly from the base of the NAC. Tumor at the base has been found to correlate with NAC tumor involvement.19 Intraoperative frozen section analysis has provided preliminary findings that allow the NAC to be excised at the initial surgery if indicated; therefore, immediate adjustments in the reconstructive procedure can be made if necessary.10,20. We found 3.7% of NACs to have tumor involvement at intraoperative evaluation with confirmation on final pathologic analysis, similar to the 2.5–12% of NACs with tumor involvement reported in other series.8,13,20 Furthermore, NAC base analysis should be confirmed by final pathologic assessment with appropriate excision of the NAC at a second surgical intervention if tumor involvement is identified. Interestingly, as in our study, many studies have identified the predominant histologic type of the involved NAC to be DCIS.18,19,21 Similar to other reported series, among patients in our study who underwent risk-reduction NSM and had occult disease identified on final pathologic analysis, none had NAC tumor involvement.19

The risk of perioperative complications is high with NSM. Several studies have evaluated skin flap and NAC complications.14,17,18,20,22 Skin flap necrosis rates of 3.4–10% have been previously reported.14,17,18 Overall, the 9.3% skin flap necrosis rate in our cohort compares favorably with the published literature. Sacchini et al.17 found a low NAC necrosis rate of 11%, with 59% of these judged to be minimal. Crowe et al.20 reported a comparable NAC necrosis rate of 5.5%. Similarly, we found a 7.4% NAC necrosis rate that required excision for treatment. This low rate of necrosis can be attributed to the selection criteria for this study and the meticulous dissection at the NAC base with the intent to minimize complications.

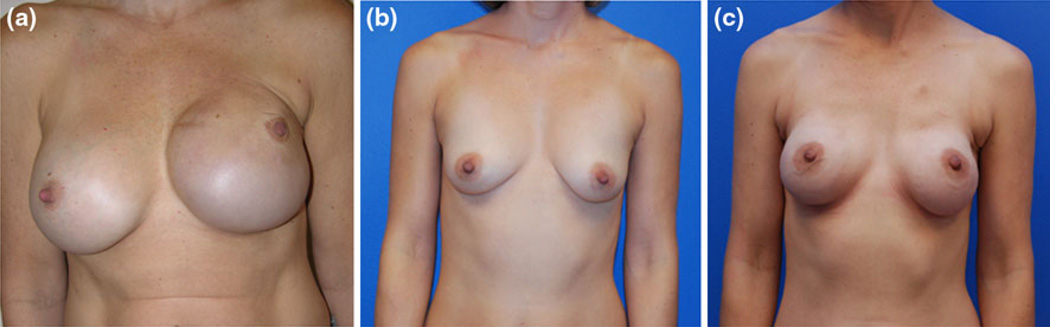

Despite the potential cosmetic benefit that NAC preservation offers, few studies have documented these outcomes.8–10,18Boneti et al.8 reported that patient self-rated cosmetic scores were higher in patients who had undergone NSM than in patients who had undergone SSM. Gerber et al. assessed the aesthetic outcomes comparing cohorts similar to those of Boneti.10 When both patients and surgeons assessed aesthetic outcomes, the surgeons’ scores were more critical than patients’ self-assessments. When Gerber et al.9 had surgeons judge aesthetic outcomes, they found a shift from “excellent” to “good” for patients who received adjuvant radiotherapy. Our detailed scoring of the breast and NAC is unique to this study, exhibiting the importance of the breast mound separate from the NAC. The majority of patients in this study were judged to have a score of good or greater for both the breast and the NAC. However, the optimal location for the incision to preserve blood supply and provide visual exposure while achieving excellent cosmetic outcomes remains in question. Our data suggest that incisions in the lateral aspect of the breast may contribute to lateral displacement of the breast and NAC, thus diminishing the overall cosmetic outcome. Additional experience with other incision locations and types of reconstruction may improve these outcomes such as the inferolateral curvilinear incision which is hidden in the lateral mammary fold (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Cosmetic outcomes a after left unilateral NSM with areola inframammary fold incision

Few studies in the literature have formally evaluated sensation in the NAC after NSM. Yueh et al.21 reported on a small cohort of 10 patients who underwent 17 NSMs. Six women reported postoperative sensitivity to be present. In our study, 100% of evaluable patients had successful nipple erection at 6 and 12 months after surgery, although the time to erection was slower than at baseline. Anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the third, forth, and fifth intercostal nerves innervate the NAC. In a NSM sensory can be maintained through careful dissection that preserves the superficial subcutaneous branches. Erection of the NAC is of particular interest because of the desire expressed by patients for a more natural NAC than what is created after reconstruction and SSM.21

Another finding that has been underevaluated in patients undergoing NSM is patient quality of life. In particular, the components of this assessment that are related to perceived body image are important when determining the overall feasibility and patient benefit of NSM. The majority of patients in our study were not self-conscious about their dress, felt sexually attractive, and felt “like a woman.” These are key body and self-image assessments that have been concerns to patients selecting NSM.21,23

In summary, this study demonstrated the feasibility of performing NSM in an oncologically rigorous fashion with minimal perioperative complications while providing the potential for NAC sensation, improved cosmesis, and good quality of life in terms of body image satisfaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672).

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:567–575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1048–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman LA, Kuerer HM, Hunt KK, et al. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of local recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:620–626. doi: 10.1007/BF02303832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroll SS, Khoo A, Singletary SE, et al. Local recurrence risk after skin-sparing and conventional mastectomy: a 6-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:421–425. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199908000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kroll SS, Schusterman MA, Tadjalli HE, Singletary SE, Ames FC. Risk of recurrence after treatment of early breast cancer with skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:193–197. doi: 10.1007/BF02306609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laronga C, Kemp B, Johnston D, Robb GL, Singletary SE. The incidence of occult nipple–areola complex involvement in breast cancer patients receiving a skin-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:609–613. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0609-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santini D, Taffurelli M, Gelli MC, et al. Neoplastic involvement of nipple–areolar complex in invasive breast cancer. Am J Surg. 1989;158:399–403. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boneti C, Yuen J, Santiago C, et al. Oncologic safety of nipple skin-sparing or total skin-sparing mastectomies with immediate reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber B, Krause A, Dieterich M, Kundt G, Reimer T. The oncological safety of skin sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple–areola complex and autologous reconstruction: an extended follow-up study. Ann Surg. 2009;249:461–468. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a044f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber B, Krause A, Reimer T, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple–areola complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure. Ann Surg. 2003;238:120–127. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000077922.38307.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlajcic Z, Zic R, Stanec S, Lambasa S, Petrovecki M, Stanec Z. Nipple–areola complex preservation: predictive factors of neoplastic nipple–areola complex invasion. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:240–244. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000171680.49971.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simmons RM, Brennan M, Christos P, King V, Osborne M. Analysis of nipple/areolar involvement with mastectomy: can the areola be preserved? Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:165–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02557369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voltura AM, Tsangaris TN, Rosson GD, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: critical assessment of 51 procedures and implications for selection criteria. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3396–3401. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolier AJ, Sullivan SK, Dellacroce FJ. Technical considerations in nipple-sparing mastectomy: 82 consecutive cases without necrosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1341–1347. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benediktsson KP, Perbeck L. Survival in breast cancer after nipple-sparing subcutaneous mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with implants: a prospective trial with 13 years median follow-up in 216 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petit JY, Veronesi U, Orecchia R, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in association with intra operative radiotherapy (ELIOT): a new type of mastectomy for breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:47–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacchini V, Pinotti JA, Barros AC, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer and risk reduction: oncologic or technical problem? J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung KL, Blamey RW, Robertson JF, Elston CW, Ellis IO. Subcutaneous mastectomy for primary breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:343–347. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)90912-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brachtel EF, Rusby JE, Michaelson JS, et al. Occult nipple involvement in breast cancer: clinicopathologic findings in 316 consecutive mastectomy specimens. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4948–4954. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowe JP, Jr, Kim JA, Yetman R, Banbury J, Patrick RJ, Baynes D. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: technique and results of 54 procedures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:148–150. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yueh JH, Houlihan MJ, Slavin SA, Lee BT, Pories SE, Morris DJ. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: evaluation of patient satisfaction, aesthetic results, and sensation. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62:586–590. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31819fb1ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Etienne CA, Cody HS, III, Disa JJ, Cordeiro P, Sacchini V. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: initial experience at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and a comprehensive review of literature. Breast J. 2009;15:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Didier F, Radice D, Gandini S, et al. Does nipple preservation in mastectomy improve satisfaction with cosmetic results, psychological adjustment, body image and sexuality? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:623–633. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]