Abstract

Introduction

In this prospective study of localized prostate cancer patients and their partners, we analyzed how partner issues evolve over time, focusing on satisfaction with care, influence of cancer treatment and its impact on relationship with patient, cancer worry, and personal activities.

Aims

Our study aims were twofold: 1) to determine whether the impact of treatment on patients and partners moderate over time and (2) if receiving surgery (i.e., radical prostatectomy) influences partner issues more than other treatments.

Methods

Patients newly diagnosed with localized prostate cancer and their female partners were recruited from 3 states to complete surveys by mail at 3 time points over 12 months.

Main Outcome Measures

The four primary outcomes assessed in the partner analysis included satisfaction with treatment, cancer worry, and the influence of cancer and its treatment on their relationship (both general relationship and sexual relationship).

Results

This analysis included 88 patient-partner pairs. At 6 months, partners reported that cancer had a negative impact on their sexual relationship (39% - somewhat negative and 12% - very negative). At 12 months, this proportion increased substantially (42% – somewhat negative and 29% - very negative). Partners were significantly more likely to report that their sexual relationship was worse when the patient reported having surgery (p=0.0045, OR=9.8025, 95% CI 2.076–46.296). A minority of partners reported significant negative impacts in other areas involving their personal activities (16% at 6 months and 25% at 12 months) or work life (6% at 6 months, which increased to 12% at 12 months).

Conclusion

From partners’ perspectives, prostate cancer therapy has negative impact on sexual relationships, and appears to worsen over time.

Keywords: prostate cancer, partner, sexual function

Introduction

As with other major illnesses, men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer often turn to their wives or significant others, (referred to here jointly as partners), for support. The interactions between patients and partners may impact the patients’ treatment choices, perceptions of outcomes following treatment, and their relationship with each other long after cancer treatments have been completed. Despite these issues, relatively few studies have evaluated the impact of a patient’s prostate cancer treatment choice on his partner’s satisfaction with care, relationship with the patient, and quality of life. Very few studies have specifically addressed the impact of declines in patient sexual function following surgery on their partners. Studies of partners on this subject have been mixed: some suggest that partners do not view sexual relationships as a priority; others find at least some dissatisfaction with their current sexual relationship. No study has evaluated how partners’ relationships with prostate cancer patients evolves over time following treatment.

This longitudinal study evaluated partner issues and how they evolved over time, particularly the issues associated with satisfaction with care, the influence of prostate cancer and its treatment on the relationship with the patient, personal issues including satisfaction with the sexual relationship, cancer worry, and activities and plans as a couple.

Aims

We explored two lines of inquiry: (1) does the influence of treatment on the items noted above moderate over time; i.e., are the issues above less important as the time from initial treatment lengthens; and (2) does receiving surgery (i.e., radical prostatectomy) influence these partner issues more than other treatments or active surveillance?

Methods

Patient Population and Recruitment

The Family And Cancer Therapy Selection (FACTS) study conducted a prospective survey of localized prostate cancer patients and their partners at three time points. Participant recruitment was conducted at urology clinics in three states: the Medical University of South Carolina Urology Department and Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Administration Medical Center in Charleston, SC; three medical centers affiliated with the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, CA; and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the Audie Murphy Veterans Administration Medical Center in San Antonio, TX.

Eligible patients had been recently diagnosed with localized prostate cancer (AJCC Stages I-III, TNM Stages T1 – T3, N0, M0) and had not yet received primary treatment. Study coordinators or research nurses reviewed lists of newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer patients who had not been treated and were scheduled for clinic visits. If present at the treatment consultation with the patient, family members of patients were invited to participate in the study by nurses or study coordinators. Patients without family members present at their clinic visit were provided an approach packet to take home to their family member. Family members originally included non-partner relationships (son or daughter, sibling, etc.); later this analysis was restricted to partners only (both married and unmarried).

After nurses or study coordinators approached patients and partners at clinic visits and conducted informed consent, participants took home a survey to return by mail. Study coordinators conducted telephone follow-up to encourage the return of surveys. Participants received $25 after completing the baseline survey. All study methods and materials were approved by Institutional Review Boards at the study coordinating center (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) and at each recruitment site.

Patient and Partner Surveys

We posed questions to partners and patients about various aspects of their cancer treatment experience and the impact of cancer on their lives over time. Baseline surveys were completed soon after diagnosis with follow-up surveys collected six months and 12 months later. The mean time from diagnosis to participant baseline survey return was 79 days. Although this mean response time was relatively short, we do not have any information concerning sexual satisfaction prior to diagnosis. The survey development methods (focus groups followed by cognitive interviews) and the taxonomy of items are described in detail elsewhere.(1) A potential for response bias in the study cohort exists since couples who completed the 6-month and 12-month follow-up surveys may be more motivated to complete the surveys due to a negative treatment experience or unrealistic expectations regarding the patient’s recovery.

Main Outcome Measures

The four primary outcomes assessed in the partner analysis included satisfaction with treatment, cancer worry,(2–4) and the influence of cancer and its treatment on their relationship (both general relationship and sexual relationship).

Patient-specific survey items included Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC) sexual domain summary scores, a general visual analogue scale measure of overall health and satisfaction with treatment.(5) Partner survey items included personal issues (self-rated overall health using a visual analogue scale, impact on career/work life, and hours spent on chores previously handled by the patient), participation in social activities and reduced ability to “go out/leave the home.” We also included the summary mental and physical assessment questions from the SF-12 instrument.(6, 7)

Statistical Analysis

To assess the association between clinical and demographic variables on the four primary outcomes, generalized linear mixed models were used. Generalized linear mixed models are logistic regression models with a random within subject intercept to account for the correlation on the repeated 6- and 12-month observations. Randomized quantile residuals were used to graphically assess the fit of the models. Independent variables included survey time (six versus 12 months), whether the patient received surgery, the patient’s sexual baseline EPIC score, and the family member’s age at diagnosis, education, and physical and mental SF-12 score at baseline.

Results

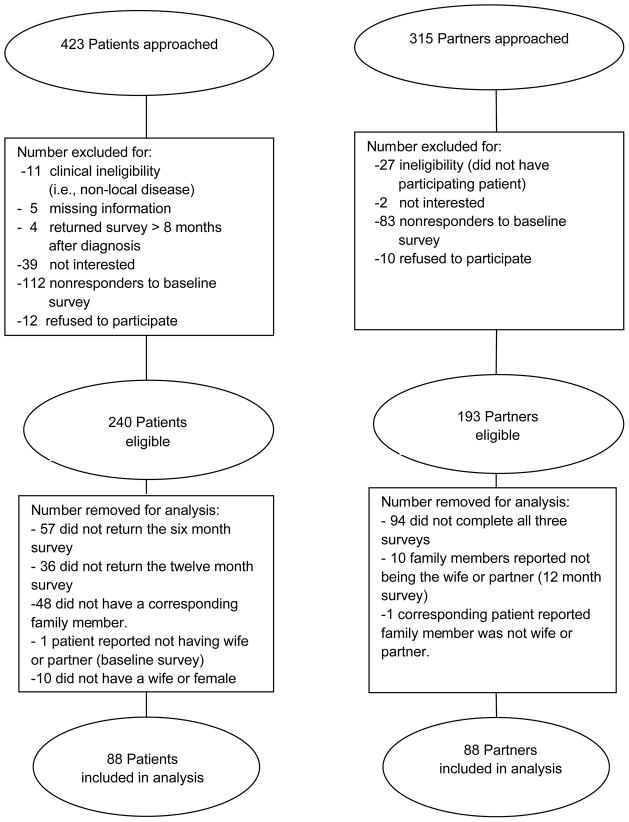

Of the 423 patients and 315 family members approached for the FACTS study, 240 patients and 193 family members were eligible for inclusion in the study. After restricting the analysis to patients and their female partners who completed all three surveys, 88 patients and 88 partners were included in the evaluation reported here (Figure 1). Patients were on average 4 years older than their female partners. Partner and patient demographics are reported in Table 1 along with the patient comorbidities, classification of patient disease risk, initial therapy, and baseline sexual satisfaction.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram for the Family And Cancer Therapy Selection (FACTS) study.

Table 1.

Participant demographics with patient comorbidities, classification of disease risk, initial therapy, and baseline sexual satisfaction.

| Patients | Partners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 88 | 100 | 88 | 100 |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 25 | 28% | 37 | 42% |

| 60–64 | 18 | 20% | 22 | 25% |

| 65–69 | 28 | 32% | 20 | 23% |

| 70 + | 17 | 19% | 8 | 9% |

| Race | ||||

| White | 74 | 84% | 68 | 77% |

| Black | 4 | 5% | 4 | 5% |

| Hispanic/Asian | 10 | 11% | 13 | 15% |

| Employment | ||||

| Full-time /Part-time/Self-employed | 60 | 68% | n/a | n/a |

| Retired/Unemployed/Unknown | 28 | 32% | n/a | n/a |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 6 | 7% | 11 | 13% |

| Some college | 20 | 23% | 27 | 31% |

| College graduate | 29 | 33% | 36 | 41% |

| Graduate degree | 30 | 34% | 14 | 16% |

| Unknown | 3 | 3% | 0 | 0% |

| Survey Site | ||||

| USC | 56 | 64% | n/a | n/a |

| UTHSCSA | 16 | 18% | n/a | n/a |

| MUSC | 16 | 18% | n/a | n/a |

| Disease Classification | ||||

| Low risk | 44 | 50% | n/a | n/a |

| Moderate/High risk | 44 | 50% | n/a | n/a |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No other health problems | 23 | 26% | n/a | n/a |

| 1 other health problem | 39 | 44% | n/a | n/a |

| 2+ other health problems | 26 | 30% | n/a | n/a |

| Initial therapy* | ||||

| Surgery | 71 | 81% | n/a | n/a |

| Brachytherapy | 8 | 9% | n/a | n/a |

| External Radiation | 15 | 17% | n/a | n/a |

| Hormone Therapy | 14 | 16% | n/a | n/a |

| Active Surveillance | 6 | 7% | n/a | n/a |

| Baseline Sexual Satisfaction** | ||||

| No or Small Problem | 65 | 74% | 68 | 77% |

| Moderate or Big Problem | 20 | 23% | 15 | 17% |

| Unknown | 3 | 3% | 5 | 6% |

USC: University of Southern California; UTHSCSA: University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; MUSC: Medical University of South Carolina

Numbers add to more than 100% due to patients choosing multiple treatments

Patient baseline question asked about overall sexual function while partner baseline question asked how bothered they were by sexual difficulties

At the 12 month follow-up survey, the majority of patients reported having received surgery (81%). Relatively small numbers of patients reported receiving radiation (17%), hormone therapy (16%), or brachytherapy (9%). Only 7% reported receiving no therapy or active surveillance. There was no statistically significant difference by site for patients who received nonsurgical therapies, however the subgroup analysis was underpowered to detect any differences between men who did and did not receive prostatectomy

Overall Assessment of Health and Satisfaction with Treatment: Comparison of Patients and Partners

As gauged by a 0–100 visual analogue scale, patients’ average overall health decreased slightly but not significantly at months six and 12 compared to baseline (baseline 84.1; six months 82.1; 12 months 80.5; p =0.3037, p = 0.0735, respectively). The partner’s mean reported overall health remained almost the same at baseline, six months, and 12 months (79.7, 81.9, 81.4, respectively). (Data not shown)

The majority of partners and patients reported being satisfied with the patient’s treatment at the six and 12-month follow-up periods (Table 2). From the generalized linear mixed model, the only factor that was significantly associated with partner treatment satisfaction was education, where partners with high school education or lower were less likely to be satisfied with treatment (p=0.046, Odds Ratio=0.1926, 95% CI 0.038–0.967). This finding is consistent with previously reported studies indicating that greater involvement in treatment decision making leads to improved partner satisfaction with treatment outcomes. (8) There were no significant associations from the regression model examining factors influencing the partner’s general relationship with the patient.

Table 2.

Patient and partner reported satisfaction with treatment.

| Satisfaction Level | Patient satisfaction | Partner satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 months (N=86) | At 12 months (N=88) | At 6 months (N=84) | At 12 months (N=88) | |

| Not At All | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) |

| Somewhat | 11 (13%) | 10 (11%) | 10 (12%) | 11 (13%) |

| Very | 36 (42%) | 30 (34%) | 32 (38%) | 22 (25%) |

| Completely | 35 (41%) | 41 (47%) | 40 (48%) | 44 (50%) |

| Not Sure | 3 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (10%) |

Patient Sexual Function and the Partner’s Perception of their Sexual Relationship

As recorded by the EPIC questionnaire, patient’s reported urinary incontinence and sexual function declined from baseline to six months, then improved somewhat at 12 months. However, at 12 months sexual function and urinary incontinence scores were still significantly lower than baseline (p< 0.0001). Bowel and urinary irritative symptoms did not change appreciably over time (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient reported Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC) sexual and bowel and urinary function at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months.

| N | Mean | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel (p=0.4206) | ||||

| Baseline | 87 | 94.7 | 96.4 | 53.6–100 |

| 6 Month | 86 | 95.6 | 100.0 | 54.2–100 |

| 12 Month | 85 | 95.5 | 100.0 | 37.5–100 |

| Sexual (p<0.0001) | ||||

| Baseline | 87 | 55.7 | 65.4 | 0–94.2 |

| 6 Month | 87 | 30.7 | 18.0 | 0–95.8 |

| 12 Month | 85 | 37.5 | 36.2 | 0–100 |

| Urinary Irritative (p=0.0909) | ||||

| Baseline | 86 | 86.7 | 92.9 | 46.4–100 |

| 6 Month | 85 | 85.9 | 93.8 | 12.5–100 |

| 12 Month | 85 | 89.6 | 93.8 | 25–100 |

| Urinary Incontinence (p<0.0001) | ||||

| Baseline | 86 | 94.0 | 100 | 31.3–100 |

| 6 Month | 85 | 74.0 | 79.3 | 0–100 |

| 12 Month | 85 | 79.0 | 85.5 | 0–100 |

Higher EPIC score is better function. p-values reflect change between baseline and 12 month surveys.

At six months, a slight majority of partners reported that cancer had a negative impact on their sexual relationship (39% - somewhat negative and 12% - very negative). At 12 months, the proportion of partners reporting that the cancer had a negative impact on their sexual relationship increased substantially (42% – somewhat negative and 29% - very negative) (Table 4). Partner reports of negative impact of therapy on their sexual relationship correlated with patients reporting problems with their sexual function, and the degree of correlation increased over time (Table 5). The generalized linear mixed model regression assessing partner evaluations of the sexual relationship found that partners’ were significantly more likely to report that their sexual relationship was worse when the patient reported having surgery (p=0.0045, Odds Ratio=9.8025, 95% CI 2.076–46.296). There was no significant associations between other factors—including the patient’s baseline EPIC sexual score, the partners age, education, and SF-12 physical and mental scores—and the partner’s assessment of changes in their sexual relationship.

Table 4.

Impact of cancer and its treatment on the patient-partner relationship at follow-up.

| Patient reported relationship with partner | Partner reported relationship with patient | Partner reported sexual relationship | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 months (N=87) | At 12 months (N=87) | At 6 months (N=88) | At 12 months (N=84) | At 6 months (N=83) | At 12 months (N=83) | |

| Very Negative | 3 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 10 (12%) | 24 (29%) |

| Somewhat Negative | 18 (21%) | 13 (15%) | 7 (8%) | 10 (12%) | 32 (39%) | 35 (42%) |

| No Impact | 36 (41%) | 40 (46%) | 29 (33%) | 37 (44%) | 26 (31%) | 16 (19%) |

| Somewhat Positive | 16 (18%) | 17 (20%) | 23 (26%) | 23 (27%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (5%) |

| Very Positive | 11 (13%) | 11 (13%) | 26 (30%) | 12 (14%) | 6 (7%) | 2 (2%) |

Table 5.

Partner reported impact of cancer on sexual relationship, alongside patient reported overall problem with sexual function (both at 6 months and 12 months).

| Partner reported impact on sexual relationship* | Patient overall sexual function 6 Months (column %) | Patient overall sexual function 12 Months (column %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No or small problem | Problem | No or small problem | Problem | |

| Same or better | 21 (58%) | 14 (34%) | 15 (38%) | 7 (18%) |

| Worse | 15 (42%) | 27 (66%) | 25 (63%) | 33 (83%) |

‘No or small problem’ includes responses that indicated no problem, very small problem, or small problem.

‘Problem’ includes responses that indicated moderate problem or big problem.

‘Same or better’ includes partner responses that indicated no impact, somewhat positive impact or very positive impact.

‘Worse’ includes partner responses that indicated very negative impact or somewhat negative impact.

At 6 months, the percent agreement between patient and partner is (21+27)/77 = 62% At 12 months, agreement is (15+33)/80 = 60%.

Partners’ Cancer Worry

At baseline 42% (n=37) of partners agreed with the statement that they were worried the patient’s cancer would worsen; this number decreased to 26% (n=23) and 23% (n=20) at the six and 12 month follow-up surveys respectively (data not shown). The generalized linear mixed model found that partners who are white (versus all other races) were less likely to be worried that their loved one’s cancer will get worse (p=0.0389, Odds Ratio=2.8848, 95% CI 1.057–7.873). Other factors were not significantly associated with cancer worry.

Impact on Partners’ Work and Activities

A majority of partners reported that the cancer experience had no impact on their work life/career (84% at six months and 80% at 12 months); a small percentage reported a somewhat or very negative impact on their work life/career (6% at six months, which increased to 12% at 12 months) or a somewhat positive or very positive impact on their work life/career (10% at six months, which decreased to 7% at 12 months). Over half of partners reported being retired or not working (53% before diagnosis and 59% at 12 months). Most partners did not change the number of hours they worked between the year before diagnosis and the 12 month survey (83%). Of those that did change the number of hours worked (n=15), the average change was a decrease of 21 hours (S.D.= 21). At six months, 16% (n=14) reported that the cancer diagnosis had a somewhat or very negative impact on their ability to do things they wanted to do; this number increased to 25% (n=22) at 12 months (Data not shown).

Impact on Social Activities and Activities Shared by the Couple

At six and 12 months, more than two thirds of partners reported that the patient’s cancer did not impact their participation in social activities such as going out to dinner, visiting friends, or going to the movies. The majority of partners reported that the cancer experience had no impact on their ability to leave the house at either follow-up time point (68–69%); less than one-fourth of partners reported a somewhat or very negative impact on their ability to leave the house (20% at 6 months and 19% at 12 months). Similarly, at 12 months the majority of partners (86%) reported they spent less than one hour per week or no time on chores the patient used to do prior to diagnosis (Data not shown).

Discussion

We conducted a longitudinal, multi-site survey to better understand the impact of localized prostate cancer and its treatment on partners of men with prostate cancer, focusing on how it affected several personal issues and their relationships. Although their satisfaction with the treatment was generally high, the proportion of partners reporting problems with their sexual relationship increased substantially between six months and 12 months, such that at 12 months, more than seven out of 10 partners reported somewhat or very negative impacts on their sexual relationship. In contrast, a minority of partners reported significant negative impacts in other areas involving their relationship or their personal activities, including work. While our study did not directly assess the impact of urinary function on men’s quality of life, previous studies have reported that impaired urinary function did not limit social, physical or occupational activities for the majority of men. (9, 10) Partner’s worry about the patient’s cancer declined substantially over time. The partner reports about the negative impact on their sexual relationship were largely mirrored by the patient reports, including self-reports of difficulty as measured by the sexual function subscale of the EPIC questionnaire. Partners were significantly more likely to report longer-term problems with their sexual relationship when the patient received surgery versus other therapies or active surveillance.

We suspect that the decline in partner’s perception of their sexual relationship with the patient is not a function of continued declines in patient sexual function. Average and median patient sexual function scores from the EPIC questionnaire improved slightly between 6 and 12 months, albeit rather modestly and well below baseline. Rather, we propose that the continued poor function of patients was associated with partner expectations that the couples sexual life would not improve as time from treatment progressed. In agreement with this hypothesis, a psychological incongruence of adjustment study by Ezer et al.(11) reported incongruent perceptions for couples through the first year of prostate cancer treatment with regard to sexual symptoms and psychological distress. Although our study did not collect information on patient or partner expectations directly, our data indicate that a substantial fraction of partners who did not report problems at six months changed their responses (in the negative) 12 months after diagnosis. Many partners probably felt that a six month recovery period was to be expected, but at one year lost hope that their sexual relationship was going to return to the pre-therapy state.

While the negative impact of prostate cancer therapy on men’s sexual function is well-described, there has been less study of partner perspectives on this aspect of their relationship. In a review of prior literature, Couper and colleagues reported that, “the focus of concern of patients on their sexual function is not shared to an equal degree by their partners.”(12) In a cross-sectional one-time survey, Neese and colleagues found that 38% of partners reported at least some dissatisfaction with their current sexual relationship. Forty-three percent had no interest in getting help for either their or their partner’s sexual issues.(13) We did not ask about partner’s interest or intentions to seek help for sexual or other issues related to the patient’s treatment.

Although several studies have shown that distress (or worry) among partners is relatively high during the peri-diagnostic period, there is scant research to indicate how anxiety levels change over time. However, a recent study by Lambert et al. reported that partners’ anxiety rates within 4 months of the prostate cancer patient’s diagnosis were greater than both population norms and the anxiety reported by the patients themselves. (14) Another dyadic study highlighted the interdependence of psychological distress between couples, with partners of patients reporting more emotional distress being more likely to report high anxiety.. Conversely, alleviation of partner distress through emotional support and access to educational resources led to improvements in patients self-reported physical and mental health scores. (15) These findings suggest that health care practitioners may be able to address distress concerns by targeting psychosocial interventions at the level of the couple and identifying vulnerable couples who may benefit from counseling or educational tools to manage treatment-related psychological distress. Our studies have not addressed the design of interventions to assist patients and partners deal with psychological distress. Small to medium effects of distress alleviation interventions are usually found for adult cancer patients. (16)

Men have reported that the impact of prostate cancer therapy on sexual function is an important drawback of therapy. In the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study, men who received surgery initially reported poorer sexual function compared to those who had other treatments; however, this difference between treatment groups disappeared between two and five years post diagnosis, largely due to worsening function in the nonsurgical group.(17) It is possible that the difference we observed in partner’s reports of sexual problems between surgically and non-surgically treated men would decline if the men in our survey also had similar changes in sexual function over time.

We note several limitations of our study. Our sample size was comparatively small and limited to regional prostate cancer treatment centers. Moreover, our study population was disproportionately white and men primarily received radical prostatectomy as treatment, hence our results may not be generalizable to other populations, particularly underrepresented minorities and men who opted for nonsurgical treatment options.. Not all patients and partners completed all surveys, and thus our results are subject to response bias. It is also unclear what effect participating in the study may have had on patients and partners satisfaction with treatment given the low response rate for completing the surveys at all 3 time points. Our study lacked sufficient demographic data to characterize the differences between survey responders and non-responders. It is plausible that couples who completed the surveys are more motivated by their treatment experience, hence our sample may be biased towards couples who experienced more difficulties with the patient’s treatment. A drawback to dyadic study designs that has been described elsewhere (12) is the low response rate of partners compared to patients, our study typifies this finding. Finally, we could not validate patient or partner reports of specific treatments received through chart audits or other means.

Few studies have surveyed partners of prostate cancer patients directly, even though it is well established that patients and partners share in the mental and emotional disease experience.(18, 19) Our study finds that partners report negative impacts on their sexual relationship. This finding is supported by a growing body of literature suggesting that prostate cancer has adverse effects on both the patient and the partner, particularly in relation to sexual function, intimacy and communication. (20–24)

It is less clear to what extent this negative impact on sexual function is of concern to partners, in light of the Couper et al. review and another study of 156 partners of patients diagnosed with cancer (including prostate) that evaluated changes in the partner’s intimate and sexual relationship with the patient. More than half of all women in this latter study reported major decreases in their own sexual desire and intimacy.(25) Most of the studies cited in the Couper review did not extend beyond six months, whereas our data suggests that worry about cancer recurrence is higher than at 12 months. Perhaps as the partners’ concern about the risk of cancer relapse eases, day-to-day issues related to the longer-term persistent sequelae of therapy become more salient.

Based on our study findings, additional insight is needed to determine whether partners perceive long-term negative effects on their sexual relationship to be a problem from their own perspective, or whether the negative report reflects their perception of their partner’s unhappiness and desire to improve it for their sake. This study should be replicated in a larger cohort with a greater representation of patients who opt for non-surgical treatment options to determine whether our study findings are relevant to patients who do not receive a prostatectomy. Given the increasing number of prostate cancer survivors, future research is needed to characterize the long-term impact of the disease burden on couples’ physical and mental health, communication, relationship satisfaction and the impact on daily life for all treatment types, including nonsurgical treatment options.. Such assessments are critical to providing the educational resources and effective psychosocial interventions to support couples surviving prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

Research Support:

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 1-U48-DP-000050 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Centers Program, through the University of Washington Health Promotion Research Center. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additional support for the UTHSCSA program was provided by funding from the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (CA054174). Case ascertainment for the developmental focus group research was supported by the Cancer Surveillance System of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, which is funded by Contract No. N01-PC-35142 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute with additional support from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the State of Washington.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Drs. Ingrid Hall, Judith Lee Smith and Donatus Ekwueme are employees of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the primary funding agency for this research. Other authors have no conflicts of interest pertaining to the information reported in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Zeliadt SB, Moinpour CM, Blough DK, Penson DF, Hall IJ, Smith JL, et al. Preliminary treatment considerations among men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(5):e121–30. Epub 2010/05/12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth AJ, Rosenfeld B, Kornblith AB, Gibson C, Scher HI, Curley-Smart T, et al. The memorial anxiety scale for prostate cancer: validation of a new scale to measure anxiety in men with with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2910–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta SS, Lubeck DP, Pasta DJ, Litwin MS. Fear of cancer recurrence in patients undergoing definitive treatment for prostate cancer: results from CaPSURE. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1931–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091993.73842.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark JA, Bokhour BG, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Measuring patients’ perceptions of the outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Med Care. 2003;41(8):923–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klabunde CN, Reeve BB, Harlan LC, Davis WW, Potosky AL. Do patients consistently report comorbid conditions over time?: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. Med Care. 2005;43(4):391–400. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156851.80900.d1. Epub 2005/03/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Stanford JL, Gilliland FD, Hamilton AS, Albertsen PC, et al. Prostate cancer practice patterns and quality of life: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(20):1719–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.20.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Moinpour CM, Blough DK, Fedorenko CR, Hall IJ, et al. Provider and partner interactions in the treatment decision-making process for newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011;108(6):851–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09945.x. discussion 6–7. Epub 2011/01/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potter SR, Partin AW. Urinary incontinence after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Reviews in urology. 1999;1(2):97–8. Epub 2006/09/21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrader-Bogen CL, Kjellberg JL, McPherson CP, Murray CL. Quality of life and treatment outcomes: prostate carcinoma patients’ perspectives after prostatectomy or radiation therapy. Cancer. 1997;79(10):1977–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970515)79:10<1977::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-r. Epub 1997/05/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezer H, Rigol Chachamovich JL, Chachamovich E. Do men and their wives see it the same way? Congruence within couples during the first year of prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:155–64. doi: 10.1002/pon.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couper J, Bloch S, Love A, Macvean M, Duchesne GM, Kissane D. Psychosocial adjustment of female partners of men with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2006;15(11):937–53. doi: 10.1002/pon.1031. Epub 2006/03/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: a phone survey of men’s and women’s perspectives. Psychooncology. 2003;12(5):463–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.657. Epub 2003/07/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambert SD, Girgis A, Turner J, McElduff P, Kayser K, Vallentine P. A pilot randomized controlled trial of the feasibility of a self-directed coping skills intervention for couples facing prostate cancer: rationale and design. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:119. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-119. Epub 2012/09/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw CK, Smith TG. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):230–8. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y. Epub 2008/03/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Kuffner R. effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Penson DF, et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(18):1358–67. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanton V, Osborne D, Dale J. Maintaining control over illness: a model of partner activity in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19(3):329–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01047.x. Epub 2009/10/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Illingworth N, Forbat L, Hubbard G, Kearney N. The importance of relationships in the experience of cancer: a re-working of the policy ideal of the whole-systems approach. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2010;14(1):23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.06.006. Epub 2009/09/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2689–700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. Epub 2005/11/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harden JK, Northouse LL, Mood DW. Qualitative analysis of couples’ experience with prostate cancer by age cohort. Cancer nursing. 2006;29(5):367–77. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00004. Epub 2006/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galbraith ME, Pedro LW, Jaffe AR, Allen TL. Describing health-related outcomes for couples experiencing prostate cancer: differences and similarities. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(5):794–801. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.794-801. Epub 2008/09/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jani AB, Hellman S. Early prostate cancer: clinical decision-making. Lancet. 2003;361(9362):1045–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penson DF, Litwin MS, Aaronson NK. Health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169(5):1653–61. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000061964.49961.55. Epub 2003/04/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkins Y, Ussher J, Gilbert E, Perz J, Sandoval M, Sundquist K. Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer nursing. 2009;32(4):271–80. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b5a93. Epub 2009/05/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]