Abstract

Heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) is a chaperone protein, and its expression is increased in response to various stress stimuli including anticancer chemotherapy, which allows the cells to survive and causes drug resistance. We previously identified lead compounds that bound to Hsp27 and tubulin via proteomic approaches. Systematic ligand based optimization in the current study significantly increased the cell growth inhibition and apoptosis inducing activities of the compounds. Compared to the lead compounds, one of the new derivatives exhibited much better potency to inhibit tubulin polymerization but a decreased activity to inhibit Hsp27 chaperone function, suggesting that the structural modification dissected the dual targeting effects of the compound. The most potent compounds 20 and 22 exhibited strong cell proliferation inhibitory activities at subnanomolar concentration against 60 human cancer cell lines conducted by Developmental Therapeutic Program at the National Cancer Institute and represented promising candidates for anticancer drug development.

1. INTRODUCTION

The expression of heat shock proteins (Hsp) is increased under lethal conditions, which is a typical response when cancer cells are stressed by chemotherapies.1–3 Hsp27, a small heat shock protein, shows a very tight correlation with anticancer drug resistance.3,4 Its overexpression enhances the survival of mammalian cells exposed to anticancer agents.5 The Hsp27 protective effects come from its molecular chaperone functions at multiple control points of the apoptotic pathways to eliminate anticancer agents induced programmed cell death.6–8 Hsp27 negatively regulates the activation of pro-caspase 9 via interaction with cytochrome c and therefore blocks the formation of the apoptosome complex.7–9 In addition, Hsp27 can inhibit caspase 3 activity via direct interaction with the pro-caspase 3 molecule.10 Other evidence has demonstrated that a significant pool of Hsp27 is located in the mitochondrial fraction of thermotolerant Jurkat cells, where it functions against apoptotic stimuli by blocking the release of cytochrome c.11 Overall, Hsp27 has strong antiapoptotic properties and functions at multiple steps of the apoptotic signaling pathway.

Mammalian Hsp27 has a molecular weight of 27 kDa; however, it can form oligomeric complexes in the range 100 ± 800 kDa.9,12,13 The oligomerization of Hsp27 is a highly dynamic process that depends on the physiology of the cells, phosphorylation status of the protein, and exposure to stress.5,6,14 It has been well investigated that large oligomers of Hsp27 are required for the chaperone activity, and the oligomers protect cells from oxidative stress, whereas this activity is down-regulated by phosphorylation-driven dissociation of the large oligomers.6,9 Preventing the formation of Hsp27 large oligomers can decrease the chaperone activity and promote cell apoptosis, which has been demonstrated by the investigation on some small molecules.15 Up-regulated expression of Hsp27 leads to an overactive chaperone activity, which in turn contributes to the anticancer drug resistance.1,2 Clinically, increased level of Hsp27 in a number of cancers such as breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and leukemia has been detected.1,2,16–20 The fact that Hsp27 is often highly expressed in cells or tissues from a wide range of tumors supports the hypothesis that this protein could limit the efficacy of cancer therapy. It will be highly desirable to target Hsp27 as cancer therapy. Hsp27 modulators can decrease the protective function of the protein in cell apoptotic regulation.4,21,22 These agents exhibit promising antitumor activities in preclinical models of a variety of tumors expressing high levels of Hsp27 and may have significant clinical potential.16,21,22

So far, the most effective strategy to target Hsp27 is antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) or siRNA, which can decrease Hsp27 expression in in vitro cell culture and in vivo xenograft as well.4,22 The fourth generation ASO of Hsp27, OGX-427,16 has shown clinical evidence of antitumor activity despite the limitations associated with ASO administration. The results further underline that Hsp27 is a good anticancer target. Small molecule Hsp27 modulators without the administration problems are highly possible to show even better clinical outcomes. The difficulties of developing small molecule Hsp27 inhibitors include three critical factors: (1) Hsp27 does not have endogenous ligand, and there is no information about the binding site of the protein; (2) the dynamic oligomeric process of Hsp27 is correlated to its function, and this dynamic characteristic makes it difficult to evaluate small molecules binding to Hsp27; (3) there is an absence of clearly demonstrated Hsp27 pathway downstream proteins that are directly affected by Hsp27 inhibitors. Therefore, it is difficult to define a cellular biomarker for these small molecules.

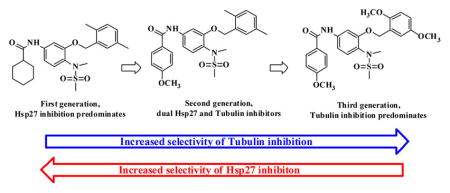

Through biotinylated small molecular probe, affinity chromatography, and proteomic approaches, we previously identified potent anticancer agents that are dual ligands binding to Hsp27 and tubulin.23,24 Systematic ligand based optimization in the current study dramatically increased the cell proliferation inhibition and apoptosis inducing activities of the compounds. The preliminary mechanism study suggests that tubulin inhibitory efficacy of the new derivatives was significantly improved, and the inhibition of the Hsp27 chaperone activity was decreased on one of the analogues. It seems that the structural modification dissected the two activities. Some of the new analogues became more potent and selective tubulin inhibitors. The structure–activity relationship (SAR) summarized from the study provided us with a foundation to further dissect the two activities and develop pure Hsp27 or tubulin inhibitors.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

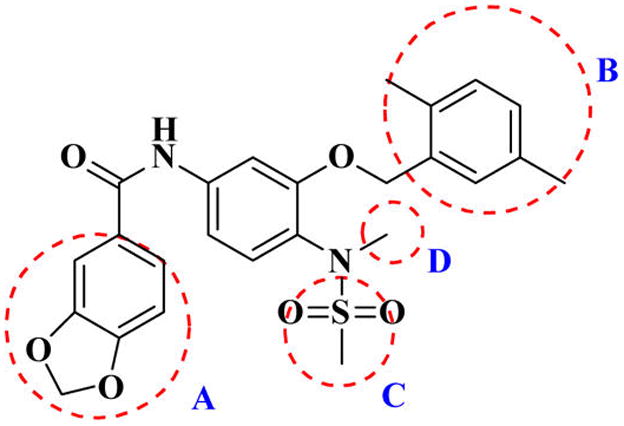

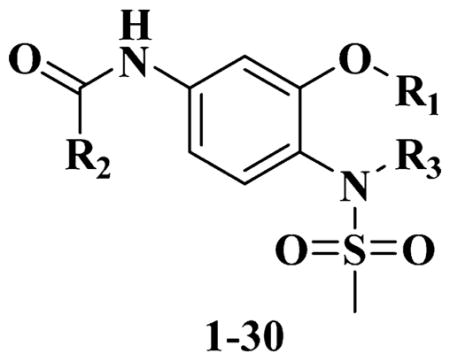

2.1. Lead Optimization and Summarization of the SAR

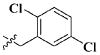

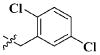

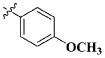

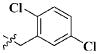

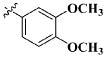

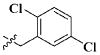

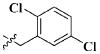

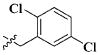

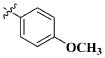

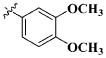

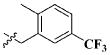

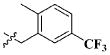

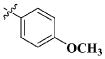

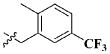

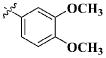

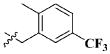

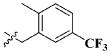

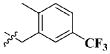

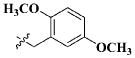

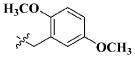

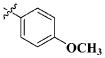

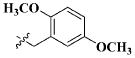

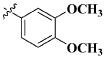

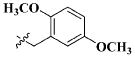

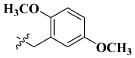

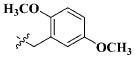

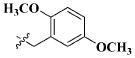

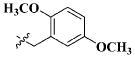

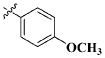

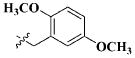

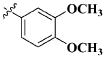

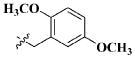

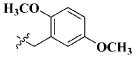

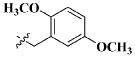

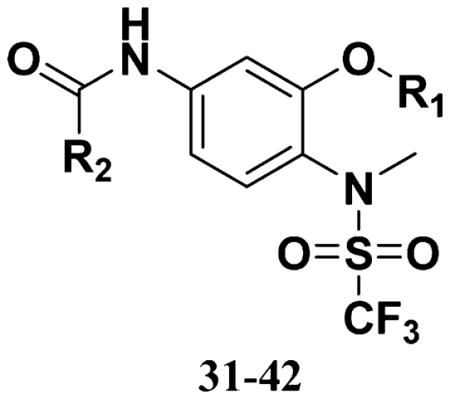

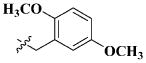

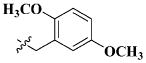

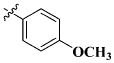

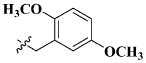

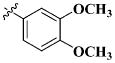

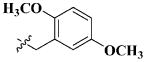

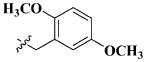

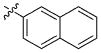

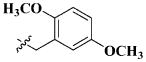

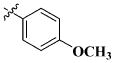

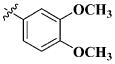

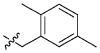

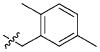

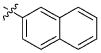

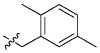

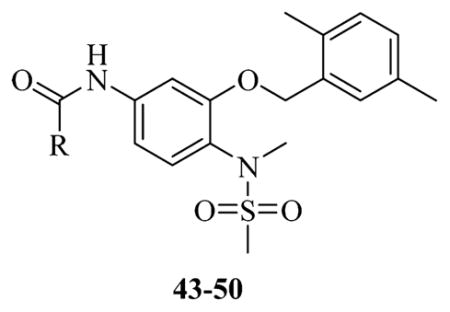

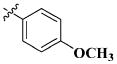

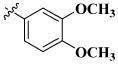

Our previous efforts to develop the potent anticancer agents led to the discovery of compound 48 (NSC751382,25 Figure 1), benzo[1,3]dioxole-5-carboxylic acid [3-(2,5-dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]amide, which displayed potent antiproliferative activity against various cancer cell lines with IC50 values in the range of 0.1–0.5 μM. The molecular targets of this compound were subsequently identified to be Hsp27 and tubulin.24 In the present study, a total of 42 new derivatives based on compound 48 were synthesized using combinatory strategy. First, we kept C and D moieties as N-methyl methylsulfonamide, and changed A and B moieties systematically (Table 1). Previous SAR study of A and B moieties revealed that 2,5-dimethylbenzyl and 2,5-dichlorobenzyl-substituted B position led to more active compounds.25,26 In the newly designed derivatives, we explored other 2,5-disubstituted benzyl groups including 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl and 2-methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyl. Additionally, n-hexyl group at the B position was also evaluated in order to determine if the hydrophobic and flexible alkyl chain could be well accommodated. Moiety A was modified to six substituted aryl groups including 4-bromophenyl, 4-methoxyphenyl, 3,4-dimethylphenyl, 4-iodophenyl, 2-naphthyl, and 3,4-methylene-dioxyphenyl. These six substituted aryl groups were previously demonstrated to be the best fit while keeping B position as 2,5-dimethylbenzyl and C position as methylsulfonamide and D position as methyl group.25 We anticipated that the new combination of A and B moieties would generate more active compounds. Additionally, the alternative to methylsulfonamide at C position was investigated by substitution with the trifluoromethylsulfonamide group. In drug design, the trifluoromethyl group is often used as a bioisostere to replace the methyl group in drug candidates for improved pharmacological activity. Trifluoromethyl is a very strong electron-withdrawing group and can form strong interactions with target protein through hydrogen bonds or polar contact. It is interesting to know whether a trifluoromethylsulfonamide group in place of the methylsulfonamide group or a trifluoromethyl group in place of the methyl group of the benzyl moiety can improve the molecular binding to target proteins and thereby increase the biological activities.

Figure 1.

Structure of compound 48.

Table 1.

SAR of A and B Moiety Methanesulfonamide

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | IC50 |

| 1 |

|

|

CH3 | 2.29 ± 1.09 μM |

| 2 |

|

|

CH3 | 0.49 ± 0.28 μM |

| 3 |

|

|

CH3 | 3.73 ± 1.81 μM |

| 4 |

|

|

CH3 | 0.66 ± 0.31 μM |

| 5 |

|

|

CH3 | 2.21 ± 0.98 μM |

| 6 |

|

|

CH3 | 2.85 ± 1.48 μM |

| 7 | n-C6H13 |

|

CH3 | 39.91 ± 16.24 μM |

| 8 | n-C6H13 |

|

CH3 | 19.98 ± 10.51 μM |

| 9 | n-C6H13 |

|

CH3 | 100.41 ± 53.14 μM |

| 10 | n-C6H13 |

|

CH3 | 12.66 ± 7.48 μM |

| 11 | n-C6H13 |

|

CH3 | 64.31 ± 44.71 μM |

| 12 | n-C6H13 |

|

CH3 | 28.76 ± 16.98 μM |

| 13 |

|

|

CH3 | 9.49 ± 5.02 μM |

| 14 |

|

|

CH3 | 2.03 ± 1.35 μM |

| 15 |

|

|

CH3 | 16.94 ± 14.51 μM |

| 16 |

|

|

CH3 | 3.50 ± 2.06 μM |

| 17 |

|

|

CH3 | 18.40 ± 15.28 μM |

| 18 |

|

|

CH3 | 14.72 ± 8.37 μM |

| 19 |

|

|

CH3 | 3.51 ± 1.91 nM |

| 20 |

|

|

CH3 | 2.56 ± 0.37 nM |

| 21 |

|

|

CH3 | 2.61 ± 1.31 nM |

| 22 |

|

|

CH3 | 1.21 ± 0.71 nM |

| 23 |

|

|

CH3 | 16.61 ± 7.71 nM |

| 24 |

|

|

CH3 | 7.52 ± 2.81 nM |

| 25 |

|

|

H | 9.58 ± 4.23 nM |

| 26 |

|

|

H | 13.40 ± 7.13 nM |

| 27 |

|

|

H | 11.0 ± 4.45 nM |

| 28 |

|

|

H | 11.83 ± 4.78 nM |

| 29 |

|

|

H | 13.27 ± 7.11 nM |

| 30 |

|

|

H | 35.25 ± 21.74 nM |

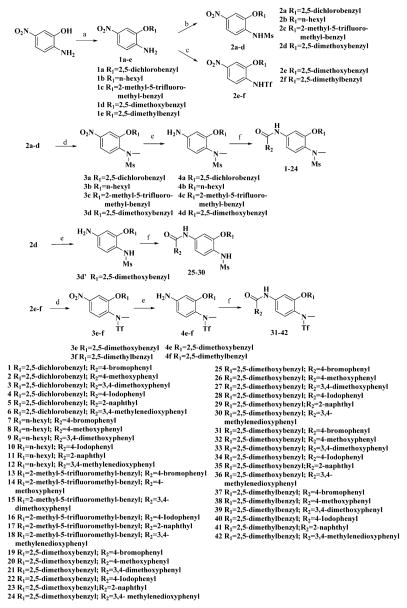

Methanesulfonamide derivatives 1–30 were prepared according to the published method (Scheme 1).25 The alkylation of the hydroxyl group of 2-amino-5-nitrophenol was followed by mesylation of the amino group by methanesulfonyl chloride and sodium hydroxide mediated hydrolysis of N,N-bismethanesulfonamide to afford the monomethanesulfonamide intermediate. This intermediate either underwent N-methylation of the sulfonamide group, reduction of the nitro group, and then amidation of amino group to yield compounds 1–24 or was directly subjected to reduction and amidation to give compounds 25–30. Our first attempt to react O-alkylated 2-amino-5-nitrophenol with trifluoromethylsulfonyl chloride in the presence of sodium hydride in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) failed to yield trifluoromethanesulfonamide. So more reactive trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride was used instead and DMF was replaced with diethyl ether as solvent, since DMF is incompatible with trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride. The obtained trifluoromethanesulfonamide intermediate was subsequently subjected to methylation, reduction, and amidation to yield the expected compounds 31–42.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 1–42a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) R1X, DMF, X = Cl, Br, or I; (b) (1) MsCl, NaH, DMF, (2) NaOH, MeOH; (c) Tf2O, NaH, Et2O; (d) MeI, NaH, DMF; (e) FeCl3, Zn, DMF/H2O; (f) R2COCl, K2CO3, 1,4-dioxane.

All the compounds were evaluated for the inhibition of SKBR-3 breast cancer cell proliferation, and the results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The IC50 values of lead compound 48 and several previously synthesized 2,5-dimethylbenzyl analogues assigned as compounds 43–49 are listed in Table 3 for comparison.25,27 The results suggest that the B moiety is critical for the antiproliferative activity of this series of compounds (Table 1). The general order of potency is 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl derivatives ≫ 2,5-dimethylbenzyl derivatives > 2,5-dichlorobenzyl derivatives > 2-methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyl derivatives > n-hexyl derivatives. The electron-donating groups on the 2,5-positions of the benzyl ring seemed to be beneficial for the biological activity. Flexible alkyl chain replacing benzyl moiety dramatically decreased the activity, suggesting that the benzyl moiety is critical for the activity. Additionally, 4-methoxybenzamide and 4-iodobenzamide analogues showed better inhibition potency than the other four amide derivatives including 4-bromobenzamide, 3,4-dimethoxybenzamide, 2-naphthylamide, and 3,4-methylenedioxybenzamide. This new combination of A and B moieties generated several potent compounds 19–24 with IC50 values at subnanomolar concentrations. Further SAR study of C and D moieties revealed the importance of the methyl group and methylsulfonylamide at the C and D positions, respectively. Removal of the N-methyl group in compounds 19–22 and 24 to afford 25–28 and 30 resulted in 3- to 10-fold loss in inhibitory potency, with the exception that compound 29 showed slightly better potency than 23. The trifluoromethylsulfonamide group replacing the methylsulfonamide group significantly impaired the cell proliferation inhibitory activity as shown in Table 2. In the case of 2,5-dimethylbenzyl derivatives, trifluoromethylsulfonamides 37–42 exhibited 35- to 207-fold lower potency than the corresponding methylsulfonamides 43–48. Similarly for 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl derivatives, trifluoromethyl sulfonamides 31–36 are 12- to 282-fold less potent than the corresponding methyl sulfonamides 19–24.

Table 2.

SAR of A and B Moiety Trifluoromethylsulfonamides

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | R2 | IC50 |

| 31 |

|

|

0.47 ± 0.21 μM |

| 32 |

|

|

0.11 ± 0.06 μM |

| 33 |

|

|

0.55 ± 0.23 μM |

| 34 |

|

|

0.51 ± 0.22 μM |

| 35 |

|

|

0.20 ± 0.09 μM |

| 36 |

|

|

0.71 ± 0.32 μM |

| 37 |

|

|

36.44 ± 28.86 μM |

| 38 |

|

|

5.32 ± 3.85 μM |

| 39 |

|

|

39.28 ± 35.11 μM |

| 40 |

|

|

13.49 ± 9.27 μM |

| 41 |

|

|

41.40 ± 34.54 μM |

| 42 |

|

|

21.78 ± 16.07 μM |

Table 3.

Previous Developed Dual Hsp27 and Tubulin Binders

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | R | IC50 |

| 43 |

|

0.22 ± 0.01 μM |

| 44 |

|

0.15 ± 0.05 μM |

| 45 |

|

0.19 ± 0.14 μM |

| 46 |

|

0.13 ± 0.07 μM |

| 47 |

|

0.21 ± 0.01 μM |

| 48 |

|

0.20 ± 0.01 μM |

| 49 |

|

3.17 ± 1.45 μM |

2.2. Cell Cycle Studies

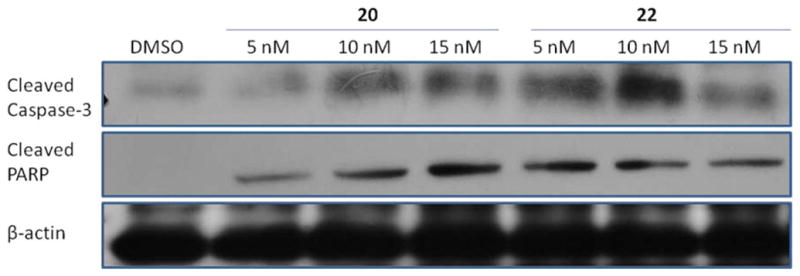

The lead compound 48 was identified to be dual Hsp27 and tubulin binder24 and exhibited significant cell cycle arrest activity in our previous studies.25 Some of the newly generated derivatives such as 19–24 displayed significantly improved cytotoxicity. It is necessary to determine if the new potent derivatives still retain the antimitotic activity of the lead compound, which is characterized by G2/M phase cell accumulation.25 Two representative compounds 20 and 22 were examined to elucidate the anticancer mechanism. Both compounds inhibited SKBR-3 cell proliferation with IC50 of around 2 nM. When the cells were treated with 1 nM of the two compounds, a significant amount of cells were halted at sub-G1 phase after 24 h, suggesting cell apoptosis. When the dosage was increased to 2.5 and 5 nM for compound 20, cells started to accumulate at G2/M phase as well as sub-G1 phase after 24 h (Table 4). However, for compound 22, 2.5 and 5 nM treatment clearly induced sub-G1 phase cell accumulation after 24 h, but a significant G2/M phase cell accumulation was only observed at 50 nM. The results suggest that compounds 20 and 22 displayed different antimitotic potency, and compound 20 is possibly more active to target tubulin. Apparently, the structural optimization improved the antimitotic effect of the lead compound 48 that affected the cell cycle at 200 nM.25 Particularly, compound 20 showed cell cycle arrest activity at a concentration as low as 2.5 nM. In addition, both compounds at subnanomolar concentrations clearly induced sub-G1 phase cell accumulation, suggesting that both compounds exhibited potent cell apoptosis inducing activity. To confirm this effect, we checked caspase 3 and its downstream protein poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) after the treatment with the two compounds. The protein levels of cleaved caspase 3, and cleaved PARP were remarkably increased after a 24 h treatment of SKBR-3 cells with compounds 20 and 22 (Figure 2). The results indicate that these small molecules can promote caspase 3 activation and thereby induce cell apoptosis.

Table 4.

Summary of Altered Cell Cycle Distribution in Response to Treatment with 20 and 22a

| concn | sub-G1 (%) | G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 3.23 | 69.63 | 16.34 | 10.77 |

| 1.0 nM 20 | 17.10 | 61.21 | 8.71 | 12.78 |

| 2.5 nM 20 | 27.43 | 34.91 | 8.92 | 28.57 |

| 5.0 nM 20 | 33.54 | 32.02 | 8.83 | 25.47 |

| 1.0 nM 22 | 14.73 | 66.68 | 8.45 | 9.24 |

| 2.5 nM 22 | 22.02 | 60.08 | 9.49 | 8.10 |

| 5.0 nM 22 | 24.27 | 51.84 | 9.51 | 13.76 |

| 50.0 nM 22 | 32.88 | 31.22 | 11.39 | 24.32 |

SKBR-3 cells were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of compounds. Cells were processed for FACS using propidium iodide staining as described. The percent distribution of cells in each cell cycle phase is displayed.

Figure 2.

Compounds 20 and 22 induced SKBR-3 cell apoptosis. SKBR-3 cells were treated with DMSO and compounds 20 and 22 for 24 h. Apoptosis was characterized by Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP as described in Experimental Section.

2.3. Inhibition of Tubulin Polymerization

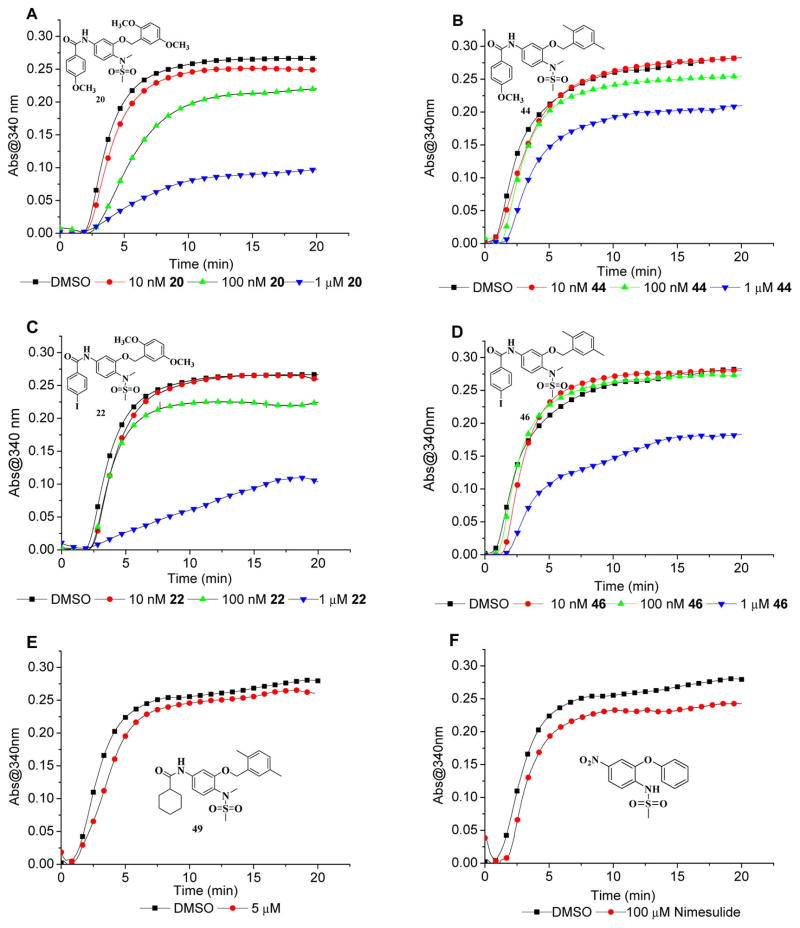

Lead compound 48 in a previous study inhibited tubulin polymerization in the enzyme and live-cell assays.24 Compared to compound 48 and several previously synthesized analogues, the new derivatives 20 and 22 in this study displayed much more potent antimitotic activity in subnanomolar concentrations. We wonder if the cell cycle arrest activity is correlated with the tubulin polymerization inhibitory potency. Therefore, compounds 20 and 22 as well as their respective structural analogues 44 and 46 were examined with the tubulin polymerization assay to analyze the correlation. As shown in Figure 3, all four compounds inhibited tubulin polymerization in a dose dependent manner. In 15 min, compound 44 inhibited tubulin polymerization by 8% at 100 nM and 25% at 1 μM. Compared to 44, compound 20 displayed more potent tubulin polymerization inhibition by 5% at 10 nM, 19% at 100 nM, and 66% at 1 μM. Compound 22 showed improved activity compared to compound 46 as well. 22 and 46 at 1 μM inhibited tubulin polymerization by 64% and 34%, respectively. The results suggest that the structural modification by substitution of 2,5-dimethylbenzyl group in compounds 44 and 46 with 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl group obviously increased their tubulin inhibitory activity. Moreover, 4-methoxybenzoxyamides at 100 nM showed more potent tubulin inhibition than the corresponding 4-iodobenzoxyamides, which is demonstrated by 20 versus 22 and 44 versus 46. The tubulin inhibitory activities of compounds 20 and 22 match the cell cycle arrest activities very well. To summarize the tubulin inhibitory activity of the series of compounds, the earlier version lead compound and the first generation compound 49 (JCC76)27,28 was also examined, and it slightly inhibited tubulin polymerization by 5% at 5 μM. The very first lead compound cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitor nimesulide28 showed about 14% tubulin inhibition at 100 μM (Figure 3). This suggests that along the lead optimization, the tubulin targeting effects of the compounds have significantly improved.

Figure 3.

Tubulin polymerization in the presence of different concentrations of compounds 20, 22, 44, 46, 49 and nimesulide.

2.4. Hsp27 Targeting Effect Investigation

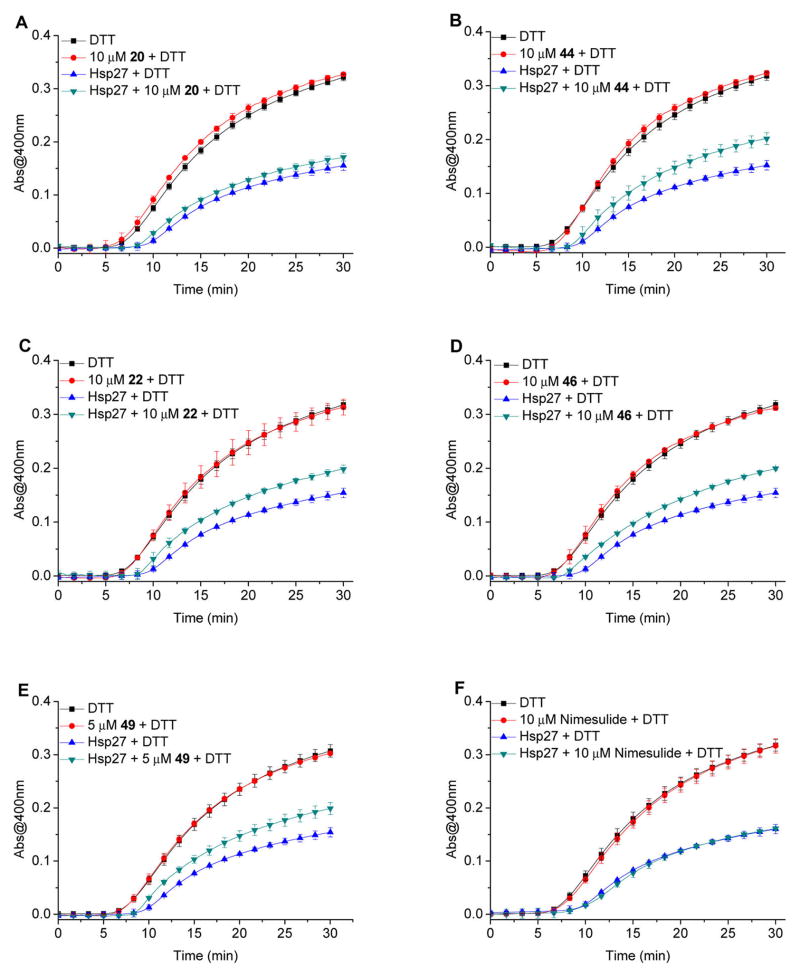

Although the lead compound 48 binds to Hsp27 and tubulin, it is still unclear if the compound affects Hsp27 chaperone activity.24 It is well documented that Hsp27 plays an important role in the prevention of cell apoptosis and effectively prevents protein aggregation.8,13 The cellular protective functions of Hsp27 in the apoptotic pathway are regulated by its chaperone activity, and this activity contributes to the protection of cells from stress stimuli.14 Therefore, we examined how our new derivatives and previous lead compounds regulate Hsp27 chaperone function in this study. Insulin is often used as a model substrate protein to evaluate the chaperone activity of small heat shock proteins. Dithiothreitol (DTT) reduction of insulin can induce its B chain to aggregate. However in the presence of Hsp27, the aggregation of insulin B chain can be attenuated or even completely prevented because of the formation of stable complexes between Hsp27 and the unfolded B chain.29–31 The capabilities of our compounds to modulate the in vitro chaperone function of Hsp27 were evaluated by monitoring the DTT-induced insulin aggregation in the presence of Hsp27, with or without our compounds. In the in vitro chaperone activity assays, Hsp27 exhibited strong potency against DTT-induced insulin aggregation, which was consistent with the results of other investigations.29–31 Our compounds showed inhibitory activity against Hsp27 chaperone activity in the insulin aggregation assay (Figure 4). More specifically, compound 22 at 10 μM significantly inhibited Hsp27 functions by 27%. However, compound 20 only slightly inhibited Hsp27 by 9% at 10 μM. The second generation compounds 44 and 46 exhibited similar Hsp27 inhibition. Compound 44 at 10 μM significantly inhibited Hsp27 chaperone activity by 30%. And compound 46 at 10 μM inhibited Hsp27 function by 28%. The results suggest that the structural modification dissected the tubulin and Hsp27 inhibition on some of the third generation compounds. Compound 20 showed strong tubulin inhibition but weak Hsp27 inhibition. The second-generation compounds 44 and 46 showed similar Hsp27 inhibition compared to the third generation compound 22 but exhibited relatively weaker tubulin inhibition. The compounds were much less active than third generation compounds in the cell proliferation assay. At 5 μM, first generation compound 49 showed strong Hsp27 inhibition by 29% and minimal tubulin inhibitory activity, which led to the lower cytotoxicity with an IC50 of 3.17 μM. In fact, compound 49 was the most potent Hsp27 inhibitor within the study and showed selective cytotoxicity to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2) overexpressed breast cancer cells in a previous investigation,32 which might be related to the Hsp27 and Her2 pathway interaction.33,34 The parental compound nimesulide did not show any Hsp27 inhibitory activity at 10 μM. Moreover, all these compounds were evaluated in this assay in the absence of Hsp27 and the results demonstrated that the compounds exhibited no or minimal direct chemical chaperone activity on DTT-induced insulin aggregation.

Figure 4.

Hsp27 chaperone activity for the protection of DTT induced insulin aggregation in the presence of different concentrations of compounds 20, 22, 44, 46, 49 and nimesulide. The kinetics of the DTT reduction-induced insulin aggregation was monitored in the absence of Hsp27 or in the presence of Hsp27 without or with compounds in triplicate.

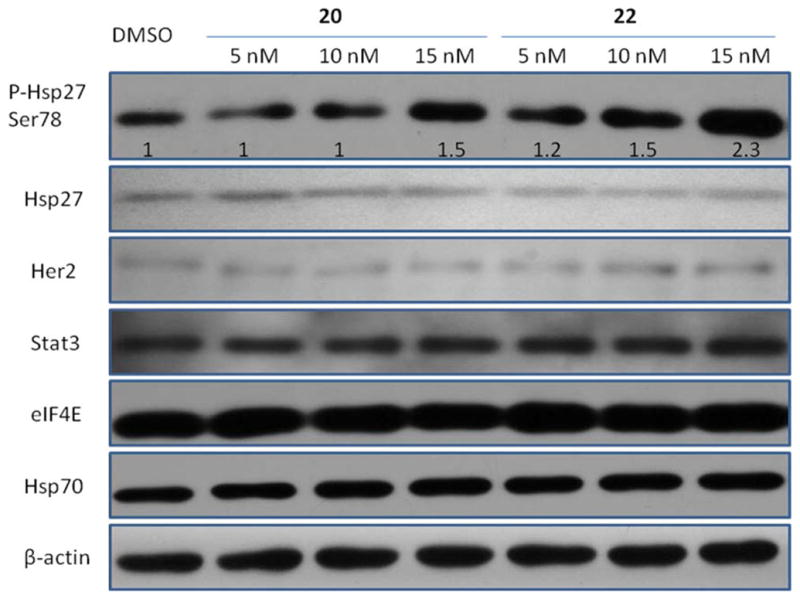

Subsequently, we examined how the third generation compounds regulated Hsp27 in cancer cells. We first checked the levels of phosphorylated Hsp27 (pHsp27) and total Hsp27 in SKBR-3 breast cancer cells after a 24 h treatment with 20 and 22. pHsp27 levels were significantly increased by both compounds at concentrations close to their IC50 values to inhibit cell growth (Figure 5). Since compound 20 did not show significant Hsp27 inhibition at 10 μM in the enzymatic assay but still stimulated cellular pHsp27, we speculate that the increased pHsp27 is not due to the Hsp27 direct targeting effect. The tubulin inhibition of these compounds might be responsible for the pHsp27 up-regulation, which has been demonstrated by other tubulin inhibitors such as vinblastine and paclitaxel.35 Cells activate pHsp27 as a defending mechanism after being stressed by tubulin inhibitors. The results suggest that compound 22 did not directly change Hsp27 total protein, and the up-regulated Hsp27 phosphorylation was due to the tubulin effect, even the compound inhibited Hsp27 chaperone activity. Hsp27 has chaperone activity and can stabilize its client proteins. As an Hsp27 binder, compound 22 might affect the cellular Hsp27 chaperone function and decrease the stability of the Hsp27 client proteins. We checked several representative proteins including Her2,18 eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E),36 signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3),37 and 70 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70),38 which have been reported to interact with Hsp27. These proteins in SKBR-3 cells were determined via Western blot after the treatment with compounds 20 and 22. The results indicated that the protein levels of Her2, eIF4E, Stat3, and Hsp70 remained nearly constant after the treatment, which suggests that our Hsp27 inhibitor did not affect the stability of Her2, eIF4E, Stat3, and Hsp70 in SKBR-3 cells. As a general chaperone protein, Hsp27 has many client proteins. It is very desirable to identify some of these proteins that are sensitive to Hsp27 small molecule inhibitors, which can be used as a biomarker for Hsp27 inhibitor characterization. Although we did not find such a biomarker within the four Hsp27 client proteins, further investigation will be executed when more Hsp27 client proteins are discovered.

Figure 5.

Effect of compounds 20 and 22 on Hsp27 and several Hsp27 interactive proteins. SKBR-3 cells were treated with DMSO and compounds 20 and 22 for 24 h. Levels of pHsp27, Hsp27, Her2, Stat3, eIF4E, and Hsp70 were analyzed by Western blot of cell extracts with specific antibodies as described in Experimental Section. The bands for pHsp27 were quantified using ImageJ (NIH) and normalized to β-actin.

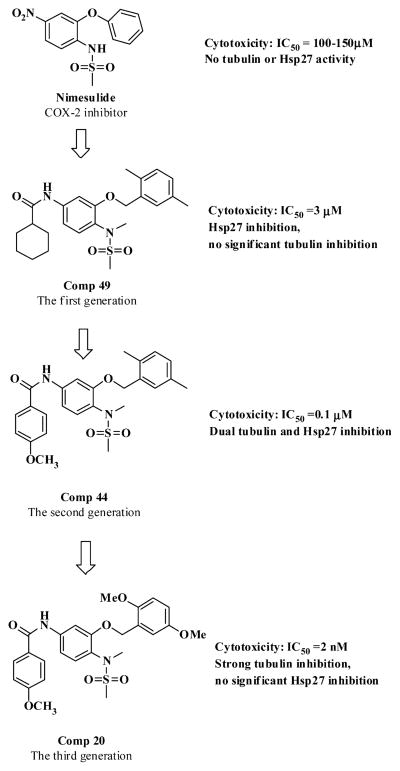

So far, our dual tubulin and Hsp27 inhibitor development has gone through three major stages, which can be represented by the three generations of compounds (Figure 6). The first generation compound 49 (JCC76)27,28 was developed based on the COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide and showed promising antiproliferative activity with an IC50 of 3.17 μM. Examination of 49 with tubulin and Hsp27 enzymatic assays revealed that the compound mainly inhibited Hsp27 activity. The parental compound nimesulide did not show significant activities in the tubulin and Hsp27 assays. Apparently, the structural modification based on nimesulide as a platform led to novel tubulin and Hsp27 dual inhibitor, which was totally independent of COX-2 activity. The further ligand-based optimization of compound 49 resulted in the second generation of derivatives including compounds 43–48, which exhibited significantly improved cell growth inhibitory activity with IC50 of 0.1–0.2 μM.25 The mechanism investigation demonstrated that the tubulin inhibition of compounds 44 and 46 was greatly improved. And the Hsp27 chaperone inhibition of 44 and 46 was decreased compared to 49. In the current study, we further optimized the second generation of compounds and generated a series of extremely potent antiproliferative agents such as compounds 20 and 22 with IC50 of around 2 nM. The mechanism investigation revealed that the Hsp27 effect of compound 20 was almost diminished, which was accompanied by a dramatic increase in tubulin inhibition. However, compound 22 still retained similar Hsp27 inhibition and also obtained a significant increase in tubulin inhibition compared to its second generation analogue 46. The dual targeting effects of compound 22 have made it the most active analogue in the current study. Unexpectedly, we successfully dissected the two activities on compound 20.

Figure 6.

Development of potent anticancer agents from COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide to compound 20.

2.5. Broad Anticancer Activities

Because of the higher cytotoxic characteristics of compounds 20 and 22 on SKBR-3 breast cancer cells, they were submitted to the Developmental Therapeutic Program at the National Cancer Institute for screening against 60 human cancer cell lines, representing leukemia, melanoma, and cancers of the lung, colon, CNS, ovary, renal, prostate, and breast. Sixty cell lines from each class of cancer cells were incubated for 48 h with compounds 20 and 22 of various concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 100 μM. GI50 (50% of growth inhibition), TGI (total growth inhibition), and LC50 (loss of 50% of the initial cell protein) were calculated and summarized (Supporting Information). Compounds 20 and 22 exhibited extensive anticancer activity by inducing 50% of growth inhibition of most cell lines at concentrations less than 10 nM. These data (Supporting Information) clearly demonstrate the in vitro efficacy of compounds 20 and 22.

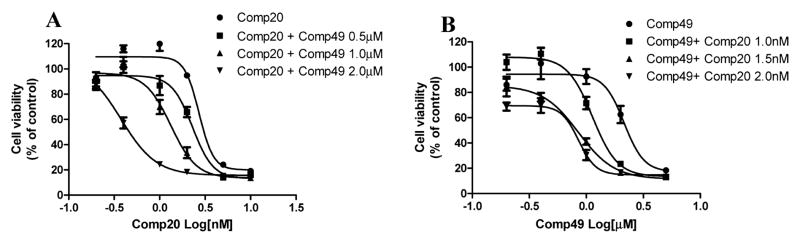

2.6. Investigation of the Combination Treatment with Hsp27 Inhibitor and Tubulin Inhibitor

Hsp27 modulators exhibited synergistic anticancer effect when they were combined with other chemotherapeutic agents.4,16,21,22,39,40 On the basis of our mechanism investigation, the first generation compound 49 mainly targeted Hsp27 chaperone activity, and the third generation compound 20 was almost a pure tubulin inhibitor. It would be interesting to see if the combination of compounds 49 and 20 could show an additive effect to inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Compound 49 at 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μM significantly shifted the cell growth inhibition curve of compound 20 to the left, suggesting that compound 49 could promote the activity of compound 20 (Figure 7A) despite that compound 49 alone did not show any cytotoxicity at 0.5 and 1.0 μM (Figure 7B). Similarly, when we combined compound 20 at 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 nM with various concentrations of compound 49, the cell growth inhibition curve of 49 was shifted to the left, suggesting that compound 20 could potentiate the activity of 49 as well (Figure 7B). The results further demonstrated the synergistic anticancer mechanism of the first generation compound 49 and third generation compound 20.

Figure 7.

First generation compound 49 and third generation compound 20 combination treatment on SKBR-3 breast cancer cell proliferation. (A) Compound 49 at 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μM shifted compound 20 cell proliferation inhibition curve to the left, suggesting the additive effect of the two compounds. (B) Compound 20 at 1, 1.5, and 2.0 nM shifted compound 49 cell proliferation inhibition curve to the left.

3. CONCLUSION

We developed a series of potent anticancer agents with IC50 values at subnanomolar levels to inhibit the proliferation of various cancer cell lines. Several new compounds such as 19–22 are 57- to 230-fold more active than previous lead compound 48. The significantly increased anticancer activity is mainly attributed to the structural modification by substitution of 2,5-dimethylbenzyl moiety in the lead compound with a 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl group.

These compounds mainly targeted tubulin polymerization to inhibit cancer cell proliferation. Their Hsp27 inhibition also contributed to their significant anticancer activity. The conclusion is based on the results of tubulin and Hsp27 enzymatic assays. In the tubulin polymerization inhibition and Hsp27 chaperone activity assays, two pairs of compounds, 20 versus 44 and 22 versus 46, were evaluated. The only structural difference in each pair of compounds is the 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl moiety in the former and the 2,5-dimethylbenzyl moiety in the latter compounds. The results indicated that the new analogues 20 and 22 exhibited much better tubulin inhibition compared to 44 and 46, which led to the dramatic increase in their anticancer activity. Unexpectedly, the structural modification significantly decreased the Hsp27 inhibition of compound 20. We fortunately dissected the dual anticancer activities on one of the third generation of compounds. Compound 22 inhibited Hsp27 at a similar level as 46, and the dual targeting effect made this compound the most potent one in this series of new derivatives, even if it was less active than compound 20 to inhibit tubulin polymerization. The combination of the 4-methoxylbenzamide moiety and the 2,5-dimethoxybenzyl moiety of compound 20 improved the tubulin inhibitory activity and decreased the Hsp27 chaperone function inhibition. The SAR summarized in the study is very important for further drug optimization to generate more potent and selective inhibitors. Particularly, potent Hsp27 inhibitors can provide a solution to solve the drug resistance issues of many chemotherapeutic agents16,22,36 and have great clinical application potential. Future study will focus on discerning the structural fragments, which are important for Hsp27 effects, developing more selective and potent Hsp27 inhibitors, and investigating the consequence of Hsp27 modulation. The investigation of how Hsp27 inhibitors regulate Hsp27 oligomerization, its chaperone functions, and the activity/stability of its client proteins could provide important information to elucidate their anticancer mechanisms.

4. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

4.1. Chemistry

Chemicals were commercially available and used as received without further purification unless otherwise noted. Moisture sensitive reactions were carried out under a dry argon atmosphere in flame-dried glassware. Solvents were distilled before use under argon. Thin-layer chromatography was performed on precoated silica gel F254 plates (Whatman). Silica gel column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 Å (Merck, 230–400 mesh), and hexane/ethyl acetate was used as the elution solvent. Mass spectra were obtained on a Micromass quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) electrospray mass spectrometer at Cleveland State University MS facility center. All the NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz instrument in either DMSO-d6 or CDCl3. Chemical shifts (δ) for 1H NMR spectra are reported in parts per million to residual solvent protons. The purity of the final compounds was determined via HPLC (Beckman) analysis with different mobile phases (Supporting Information). All the final compounds exhibited purities above 95%. The chromatographic separation was performed on a C18 column (2.0 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm) from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA). Two mobile phases (H2O/CH3OH, H2O/CH3CN) were employed for isocratic elution with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The injection volume was 20 μL, and the UV detector was set up at 256 and 290 nm.

Intermediate compounds 1a–e, 2a–d, 3a–d, 3d′, and 4a–d were prepared according to the previously published procedures.25

Trifluoromethanesulfonamides 2e–f were prepared from aryl-substituted 2-amino-5-nitrophenols 1d–e according to a modified procedure. NaH (95% powder, 0.211g, 8.81 mmol) was added to a solution of aryl-substituted 2-amino-5-nitrophenol 1d–e (3.67 mmol) in anhydrous Et2O (70 mL) at room temperature. After being stirred for 20 min, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C and Tf2O (1.24 g, 4.4 mmol) was slowly added. The resulting mixture was continuously stirred for 1 h at 0–5 °C. Water (15 mL) was added to quench the reaction. Ether was evaporated under vacuum, and then 3 N HCl (4 mL) was added to acidify the residue. The intermediates 2e–f precipitated as a yellow solid. It was collected by filtration, washed with water, dried in air, and then used for the next reaction directly. According to the same procedures used for preparation of intermediates 4a–d, 2e–f was subjected to N-methylation to afford 3e–f followed by reduction of nitro group to give 4e–f.

N-Methyl-N-[2-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-trifluoromethanesulfonamide (3e)

Yellow solid, 59% yield for the two steps of sulfonylamidation and N-methylation; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.038 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.849 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.8 Hz), 7.493 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.036 (1H, s), 6.876 (2H, m), 5.293 (2H, s), 3.889 (3H, s), 3.775 (3H, s), 3.414 (3H, s).

N-Methyl-N-[2-(2,5-dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-nitrophenyl]-trifluoromethanesulfonamide (3f)

Yellow solid, 78% yield for the two steps of sulfonylamidation and N-methylation; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.974 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.895 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 7.531 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.242 (1H, s), 7.143 (2H, m), 5.195 (2H, s), 3.365 (3H, s), 2.374 (3H, s), 2.345 (3H, s).

N-[4-Amino-2- (2, 5-dimethoxybenzyloxy)phenyl]-Nmethyltrifluoromethanesulfonamide (4e)

Pale white solid, 96% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.115 (1H, s), 7.062 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.827 (2H, m), 6.315 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.217 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.8 Hz), 5.101 (2H, s), 3.822 (3H, s), 3.817 (2H, br), 3.783 (3H, s), 3.359 (3H, s).

N-[4-Amino-2-(2,5-dimethylbenzyloxy)phenyl]-N-methyltrifluoro-methanesulfonamide (4f)

Pale white solid, 98% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.257 (1H, s), 7.084 (3H, m), 6.319 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.234 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 5.006 (2H, s), 3.847 (2H, br), 3.312 (3H, s), 2.332 (3H, s), 2.315 (3H, s).

The final compounds 1–42 were prepared from the reaction of the corresponding substituted anilines (4a–f and 3d′) with each arylcarbonyl chloride including 4-bromobenzoyl chloride, 4-methoxybenzoyl chloride, 3,4-dimethoxybenzoyl chloride, 4-iodobenzoyl chloride, 2-naphthoyl chloride, and piperonyloyl chloride.

N-[3-(2,5-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)-phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (1)

White solid, 65% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.153 (1H, s), 7.795 (1H, s), 7.778 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.635 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.553 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.365 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.303 (2H, m), 6.946 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 5.086 (2H, s), 3.252 (3H, s), 2.878 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C22H20BrCl2N2O4S [M + H]+, 556.97; found, 556.94.

N-[3-(2,5-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)-phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (2)

White solid, 70% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.959 (1H, s), 7.919 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.860 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.550 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.311 (3H, m), 6.988 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.903 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 5.164 (2H, s), 3.884 (3H, s), 3.249 (3H, s), 2.850 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C23H23Cl2N2O5S [M + H]+, 509.07; found, 509.11.

N-[3-(2,5-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)-phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (3)

White solid, 86% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.047 (1H, s), 7.925 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.548 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.502 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.435 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 7.334 (3H, m), 6.911 (2H, m), 5.152 (2H, s), 3.960 (3H, s), 3.955 (3H, s), 3.250 (3H, s), 2.858 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H25Cl2N2O6S [M + H]+, 539.08; found, 539.12.

N-[3-(2,5-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)-phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (4)

White solid, 85% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.941 (2H, m), 7.773 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.745 (2H, m), 7.681 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.593 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.501 (1H, dd, J = 2.8, 8.4 Hz), 7.464 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 7.329 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.215 (2H, s), 3.139 (3H, s), 2.931 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C22H20Cl2IN2O4S [M + H]+, 604.96; found, 604.95.

N-[3-(2,5-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)-phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (5)

White solid, 98% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.413 (1H, s), 8.264 (1H, s), 7.948 (5H, m), 7.579 (3H, m), 7.360 (2H, m), 7.291 (1H, dd, J = 2.8, 8.8 Hz), 6.988 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 5.164 (2H, s), 3.262 (3H, s), 2.861 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C26H23Cl2N2O4S [M + H]+, 529.08; found, 529.07.

N-[3-(2,5-Dichlorobenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)-phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (6)

White solid, 84% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.953 (1H, s), 7.864 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.548 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.428 (1H, dd, J = 1.6, 8 Hz), 7.370 (2H, m), 7.311 (2H, m), 6.898 (2H, m), 6.067 (2H, s), 5.143 (2H, s), 3.247 (3H, s), 2.860 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C23H21Cl2N2O6S [M + H]+, 523.05; found, 523.09.

N-[3-(n-Hexyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (7)

White solid, 60% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.042 (1H, s), 7.836 (1H, s), 7.766 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.644 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.277 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.755 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 4.060 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.269 (3H, s), 2.936 (3H, s), 1.817 (2H, m), 1.467 (2H, m), 1.349 (4H, m), 0.911 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz). ESI-MS calculated for C21H28BrN2O4S [M + H]+, 483.10; found, 483.13.

N-[3-(n-Hexyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (8)

White solid, 58% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.889 (2H, m), 7.850 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.303 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.990 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.742 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 4.076 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.885 (3H, s), 3.271 (3H, s), 2.931 (3H, s), 1.821 (2H, m), 1.472 (2H, m), 1.350 (4H, m), 0.911 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz). ESI-MS calculated for C22H31N2O5S [M + H]+, 435.20; found, 435.22.

N-[3-(n-Hexyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (9)

White solid, 75% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.914 (2H, m), 7.503 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.406 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 7.313 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.929 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.751 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 4.084 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.966 (3H, s), 3.961 (3H, s), 3.277 (3H, s), 2.937 (3H, s), 1.828 (2H, m), 1.476 (2H, m), 1.353 (4H, m), 0.913 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz). ESI-MS calculated for C23H33N2O6S [M + H]+, 465.21; found, 465.23.

N-[3-(n-Hexyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (10)

Yellowish solid, 36% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.055 (1H, s), 7.851 (3H, m), 7.617 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.271 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.749 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 4.056 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.267 (3H, s), 2.933 (3H, s), 1.814 (2H, m), 1.467 (2H, m), 1.348 (4H, m), 0.911 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz). ESI-MS calculated for C21H28IN2O4S [M + H]+, 531.08; found, 531.13.

N-[3-(n-Hexyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (11)

White solid, 83% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.412 (1H, s), 8.297 (1H, s), 7.950 (5H, m), 7.594 (2H, m), 7.296 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.822 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 4.066 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.274 (3H, s), 2.922 (3H, s), 1.801 (2H, m), 1.458 (2H, m), 1.332 (4H, m), 0.909 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz). ESI-MS calculated for C25H31N2O4S [M + H]+, 455.20; found, 455.23.

N-[3-(n-Hexyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylmethylamino)phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (12)

Yellowish solid, 76% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.969 (1H, s), 7.839 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.425 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 7.370 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.269 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.884 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.735 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 6.065 (2H, s), 4.055 (2H, t, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.265 (3H, s), 2.934 (3H, s), 1.811 (2H, m), 1.464 (2H, m), 1.346 (4H, m), 0.909 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz). ESI-MS calculated for C22H29N2O6S [M + H]+, 449.17; found, 449.20.

N-[3-(2-Methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (13)

White solid, 78% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.026 (2H, m), 7.759 (2H, m), 7.704 (1H, s), 7.653 (2H, m), 7.548 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.365 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.330 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.835 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 5.160 (2H, s), 3.228 (3H, s), 2.783 (3H, s), 2.457 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H23BrF3N2O4S [M + H]+, 571.05; found, 571.04.

N-[3-(2-Methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (14)

White solid, 97% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.081 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.959 (1H, s), 7.860 (2H, m), 7.702 (1H, s), 7.543 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.362 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.330 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.990 (2H, m), 6.815 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 5.163 (2H, s), 3.883 (3H, s), 3.224 (3H, s), 2.770 (3H, s), 2.455 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H26F3N2O5S [M + H]+, 523.15; found, 523.15.

N-[3-(2-Methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (15)

White solid, 91% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.087 (1H, s), 8.032 (1H, s), 7.707 (1H, s), 7.534 (2H, m), 7.432 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.345 (2H, m), 6.922 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.826 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.161 (2H, s), 3.965 (3H, s), 3.955 (3H, s), 3.227 (3H, s), 2.775 (3H, s), 2.453 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C26H28F3N2O6S [M + H]+, 553.16; found, 553.15.

N-[3-(2-Methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (16)

White solid, 87% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.064 (1H, s), 8.018 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.855 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.703 (1H, s), 7.616 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.546 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.363 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.314 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.833 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 5.149 (2H, s), 3.225 (3H, s), 2.781 (3H, s), 2.451 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H23F3IN2O4S [M + H]+, 619.04; found, 619.02.

N-[3-(2-Methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (17)

White solid, 97% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.580 (1H, s), 8.592 (1H, s), 8.070 (4H, m), 7.925 (1H, s), 7.833 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.654 (3H, m), 7.506 (2H, m), 7.351 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.264 (2H, s), 3.146 (3H, s), 2.909 (3H, s), 2.470 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C28H26F3N2O4S [M + H]+, 543.16; found, 543.15.

N-[3-(2-Methyl-5-trifluoromethylbenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (18)

White solid, 84% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.032 (1H, s), 7.943 (1H, s), 7.701 (1H, s), 7.542 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 7.371 (4H, m), 6.888 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.812 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.065 (2H, s), 5.153 (2H, s), 3.223 (3H, s), 2.780 (3H, s), 2.453 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H24F3N2O6S [M + H]+, 537.13; found, 537.17.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (19)

White solid, 91% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.933 (1H, s), 7.875 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.759 (2H, m), 7.647 (2H, m), 7.327 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.012 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz), 6.882 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 6.857 (2H, m), 5.130 (2H, s), 3.783 (3H, s), 3.779 (3H, s), 3.234 (3H, s), 2.816 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H26BrN2O6S [M + H]+, 549.07; found, 549.12.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (20)

White solid, 60% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.932 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.863 (3H, m), 7.327 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.004 (3H, m), 6.853 (3H, m), 5.138 (2H, s), 3.886 (3H, s), 3.782 (6H, s), 3.232 (3H, s), 2.807 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H29N2O7S [M + H]+, 501.17; found, 501.21.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (21)

White solid, 80% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.942 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.925 (1H, s), 7.504 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.411 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 7.332 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.016 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.928 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.861 (3H, m), 5.138 (2H, s), 3.968 (3H, s), 3.961 (3H, s), 3.783 (3H, s), 3.781 (3H, s), 3.236 (3H, s), 2.810 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C26H31N2O8S [M + H]+, 531.18; found, 531.23.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (22)

White solid, 62% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.940 (1H, s), 7.872 (3H, m), 7.608 (2H, m), 7.323 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.011 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz), 6.879 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.854 (2H, m), 5.127 (2H, s), 3.782 (3H, s), 3.778 (3H, s), 3.232 (3H, s), 2,814 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H26IN2O6S [M + H]+, 597.06; found, 597.11.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (23)

White solid, 83% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.402 (1H, s), 8.153 (1H, s), 7.947 (5H, m), 7.607 (2H, m), 7.355 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.028 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz), 6.940 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 6.855 (2H, m), 5.159 (2H, s), 3.786 (3H, s), 3.782 (3H, s), 3.248 (3H, s), 2.818 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C28H29N2O6S [M + H]+, 521.17; found, 521.22.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (24)

White solid, 66% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.890 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.857 (1H, s), 7.412 (1H, dd, J = 1.6, 8 Hz), 7.368 (1H, d, J = 1.6 Hz), 7.318 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.012 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 6.891 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.852 (3H, m), 6.070 (2H, s), 5.128 (2H, s), 3.781 (6H, s), 3.230 (3H, s), 2.810 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H27N2O8S [M + H]+, 515.15; found, 515.20.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylamino)-phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (25)

White solid, 80% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.37 (1H, s), 9.02 (1H, s), 7.91(2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.76 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.68 (1H, 2.4 Hz), 7.41 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.8 Hz), 7.28 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz), 7.22 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz), 6.88 (1H, dd, J = 3.2, 8.8 Hz), 5.08 (2H, s), 3.79 (3H, s), 3.73 (3H, s), 2.87 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C23H24BrN2O6S [M + H]+, 535.05; found, 535.04.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylamino)-phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (26)

White solid, 46% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 10.159 (1H, s), 9.009 (1H, s), 7.966 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.705 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.415 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.8 Hz), 7.292 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz), 7.208 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.073 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.981 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz), 6.883 (1H, dd, J = 3.2, 8.8 Hz), 5.077 (2H, s), 3.845 (3H, s), 3.789 (3H, s), 3.730 (3H, s), 2.863 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H27N2O7S [M + H]+, 487.15; found, 487.14.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylamino)-phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (27)

White solid, 36% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.14 (1H, s), 8.99 (1H, s), 7.70 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.63 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8 Hz), 7.53 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.39 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 7.29 (1H, d, J = 2.8 Hz), 7.22 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.09 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.88 (1H, dd, J = 3.2, 8.8 Hz), 5.08 (2H, s), 3.85 (3H, s), 3.84 (3H, s), 3.79 (3H, s), 3.73 (3H, s), 2.87 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H29N2O8S [M + H]+, 517.16; found, 517.16.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylamino)-phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (28)

White solid, 56% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ δ 10.355 (1H, s), 9.031 (1H, s), 7.933 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.749 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.678 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.411 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.8 Hz), 7.282 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz), 7.223 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.979 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz), 6.881 (1H, dd, J = 2.8, 8.8 Hz), 5.077 (2H, s), 3.785 (3H, s), 3.726 (3H, s), 2.868 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C23H24IN2O6S [M + H]+, 583.04; found, 583.02.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylamino)-phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (29)

White solid, 85% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.50 (1H, s), 9.03 (1H, s), 8.59 (1H, s), 8.06 (4H, m), 7.75 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.65 (2H, m), 7.50 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 7.30 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz), 7.25 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.89 (1H, dd, J = 3.2, 8.8 Hz), 5.11 (2H, s), 3.80 (3H, s), 3.74 (3H, s), 2.88 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C27H27N2O6S [M + H]+, 507.16; found, 507.15.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(methanesulfonylamino)-phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (30)

White solid, 46% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.12 (1H, s), 9.00 (1H, s), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.58 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8 Hz), 7.51 (1H, d, J = 1.6 Hz), 7.40 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.8 Hz), 7.28 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz), 7.21 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.07 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz), 6.88 (1H, dd, J = 3.2, 9.2 Hz), 6.14 (2H, s), 5.07 (2H, s), 3,79 (3H, s), 3.73 (3H, s), 2.86 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H25N2O8S [M + H]+, 501.13; found, 501.13.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (31)

White solid, 73% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.895 (1H, s), 7.724 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.662 (1H, s), 7.623 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.280 (1H, m), 7.110 (1H, s), 7.024 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 6.834 (1H, s), 6.831 (1H, s), 5.156 (2H, s), 3.810 (3H, s), 3.779 (3H, s), 3.388 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H23BrF3N2O6S [M + H]+, 603.04; found, 603.00.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (32)

White solid, 72% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.831 (3H, m), 7.727 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.276 (1H, m), 7.129 (1H, s), 6.991 (3H, m), 6.837 (1H, s), 6.833 (1H, s), 5.183 (2H, s), 3.879 (3H, s), 3.815 (3H, s), 3.791 (3H, s).3.387 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H26F3N2O7S [M + H]+, 555.14; found, 555.13.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (33)

White solid, 61% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.875 (1H, s), 7.750 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.485 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.385 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 7.283 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.131 (1H, s), 7.007 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 6.908 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.835 (2H, m), 5.184 (2H, s), 3.959 (3H, s), 3.952 (3H,s), 3.813 (3H, s), 3.794 (3H, s), 3.393 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C26H28F3N2O8S [M + H]+, 585.15; found, 585.13.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (34)

White solid, 74% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.910 (1H, s), 7.832 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.662 (1H, s), 7.570 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.273 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.107 (1H, s), 7.017 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 6.828 (2H, s), 5.148 (2H, s), 3.806 (3H, s), 3.777 (3H, s), 3.386 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H23F3IN2O6S [M + H]+, 651.03; found, 651.00.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (35)

White solid, 92% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.645 (1H, s), 8.604 (1H, s), 8.074 (4H,m), 7.829 (1H, s), 7.658 (2H, m), 7.583 (1H, d, J = 6.4 Hz), 7.389 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.127 (1H, d, J = 3.2 Hz), 7.012 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.918 (1H, dd, J = 3.2, 9.2 Hz), 5.151 (2H, s), 3.803 (3H, s), 3.727 (3H, s), 3.367 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C28H26F3N2O6S [M + H]+, 575.15; found, 575.13.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (36)

White solid, 69% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.779 (1H, s), 7.694 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.389 (1H, dd, J = 1.6, 9.6 Hz), 7.348 (1H, d, J = 1.6 Hz), 7.279 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.122 (1H, s), 7.001 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 6.883 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz), 6.839 (1H, s), 6.835 (1H, s), 6.070 (2H, s), 5.183 (2H, s), 3.819 (3H, s), 3.792 (3H, s), 3.386 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H24F3N2O8S [M + H]+, 569.12; found, 569.10.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-bromobenzamide (37)

White solid, 81% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.874 (1H, s), 7.835 (1H, s), 7.741 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.647 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.292 (2H, m), 7.098 (2H, m), 6.953 (1H, dd, J = 2.4, 8.4 Hz), 5.103 (2H, s), 3.344 (3H, s), 2.343 (3H, s), 2.335 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H23BrF3N2O4S [M + H]+, 571.05; found, 571.04.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-methoxybenzamide (38)

White solid, 66% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.892 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.844 (3H, m), 7.291 (2H, m), 7.096 (2H, m), 6.994 (2H, m), 6.928 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 5.114 (2H, s), 3.887 (3H, s), 3.339 (3H, s), 2.347 (3H, s), 2.340 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H26F3N2O5S [M + H]+, 523.15; found, 523.14.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-3,4-dimethoxybenzamide (39)

White solid, 73% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.894 (2H, m), 7.493 (1H, d, J = 2 Hz), 7.393 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8 Hz), 7.297 (2H, m), 7.096 (2H, m), 6.921 (2H, m), 5.113 (2H, s), 3.966 (3H, s), 3.959 (3H, s), 3.343 (3H, s), 2.341 (6H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C26H28F3N2O6S [M + H]+, 553.16; found, 553.15.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-4-iodobenzamide (40)

White solid, 78% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.891 (1H, s), 7.855 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.829 (1H, m), 7.587 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.293 (2H, m), 7.092 (2H, m), 6.949 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 5.092 (2H, s), 3.340 (3H, s), 2.335 (6H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C24H23F3IN2O4S [M + H]+, 619.04; found, 619.01.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxamide (41)

White solid, 60% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.386 (1H, s), 8.098 (1H, s), 7.944 (5H, m), 7.606 (2H, m), 7.312 (2H, m), 7.097 (2H, m), 7.013 (1H, dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz), 5.133 (2H, s), 3.356 (3H, s), 2.354 (3H, s), 2.338 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C28H26F3N2O4S [M + H]+, 543.16; found, 543.15.

N-[3-(2,5-Dimethylbenzyloxy)-4-(trifluoromethanesulfonyl-methylamino)phenyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-carboxamide (42)

White solid, 66% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.851 (1H, s), 7.802 (1H, s), 7.384 (2H, m), 7.298 (2H, m), 7.095 (2H, m), 6.902 (2H, m), 6.074 (2H, s), 5.105 (2H, s), 3.337 (3H, s), 2.344 (3H, s), 2.339 (3H, s). ESI-MS calculated for C25H24F3N2O6S [M + H]+, 537.13; found, 537.12.

4.2. Biological Studies

4.2.1. Cell Culture

SKBR-3 cells were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD). The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin. FBS was heat inactivated for 30 min in a 56 °C water bath before use. Cell cultures were grown at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in a VWR CO2 incubator (Bridgeport NJ).

4.2.2. Cell Viability Analysis

The effects of the new derivatives on SKBR-3 cell viability were assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide assay in six replicates. Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium in 96-well, flat-bottomed plates for 24 h and were exposed to various concentrations of the compounds dissolved in DMSO (final concentration of ≤0.1%) in medium for 48 h. Controls received DMSO vehicle at a concentration equal to that in drug-treated cells. The medium was removed, replaced by 200 μL of 0.5 mg/mL 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide in fresh medium, and cells were incubated in the CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 2 h. Supernatants were removed from the wells, and the reduced 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide dye was solubilized in 200 μL/well DMSO. Absorbance at 570 nm was determined on a plate reader. Statistical and graphical information was determined using GraphPad Prism software (Graph-Pad Software Incorporated) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation). IC50 values were determined using nonlinear regression analysis.

4.2.3. Cell Cycle Study

For all the assays, cells were treated for the indicated time. To analyze the cell cycle profile, treated cells were fixed overnight with 70% EtOH at −20 °C and stained with propidium iodide buffer [38 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.5), 69 μM propidium iodide, and 120 μg/mL RNase A]. Samples were mixed gently and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Before the analysis by flow cytometry, 400 μL of binding buffer was immediately added to each sample. A total of 1.2 × 104 cells were acquired for each sample, and a maximum of 1 × 104 cells within the gated region were analyzed.

4.2.4. Tubulin Polymerization Assay

A mixture of 100 μL of microtubule-associated protein-rich tubulin (2 mg/mL, bovine brain, Cytoskeleton) in buffer containing 80 mM PIPES (pH 6.9), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, and 5% glycerol was mixed with DMSO (as control) or various concentrations of 20, 22, 44, 46, 49, and nimesulide in DMSO and incubated at 37 °C. Then 1 μL of 100 mM GTP was added to the mixture to initiate the tubulin polymerization and the absorbance at 340 nm was monitored over 20 min using a Varian Cary 50 series spectrophotometer.

4.2.5. Hsp27 Chaperone Activity Assay

A mixture of 0.24 mg/mL human recombinant insulin (Life Technologies), 0.02 mg/mL Hsp27 (Cell Sciences), and compounds 20, 22, 44, 46, 49, and nimesulide in 98 μL of sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, was incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, whereupon 2 μL of 1 M DTT in the same assay buffer was added to initiate the insulin aggregation. The absorbance (A) at 400 nm was monitored over 30 min using a Varian Cary 50 series spectrophotometer. A mixture of 0.24 mg/mL insulin in the absence or presence of 0.02 mg/mL Hsp27 with DMSO was used as control. The Hsp27 inhibition potency (%) of compounds at 30 min were determined by

where A(Hsp27+compound+DTT) − A(Hsp27+DTT) represents an increase of insulin aggregation level in the presence of Hsp27 with compounds compared to that in the presence of Hsp27 without compounds and ADTT − A(Hsp27+DTT) represents a decrease of insulin aggregation level caused by Hsp27.

4.2.6. Western Blot

SKBR-3 cells were treated with 5, 10, and 15 nM 20 and 22 for 24 h. The cells were lysed, briefly sonicated, and centrifuged at 12000g for 10 min. Then 30 μg of protein for each sample was boiled with 4× loading buffer for 5 min, electrophoresed on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. For cleaved caspase 3 and PARP examination, 60 μg of protein was used. The membrane was blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat milk in PBST and then incubated with specific primary antibody (Cell Signaling). After being washed, the membrane was incubated with horseradish-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling). The bands were visualized by chemiluminescence with ECL reagent (Thermo Scientific).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a startup fund from Cleveland State University and also partially supported by Grant R15AI 103889 (B.S.), Center for Gene Regulation in Health and Disease of CSU, and National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation Grants CHE-0923398 and CHE-1126384. We thank the Developmental Therapeutic Program at the National Cancer Institute for screening the compounds against 60 human cancer cell lines.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase 2

- Hsp27

heat shock protein 27

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- Her2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- eIF4E

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

- Stat3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- Hsp70

70 kDa heat shock protein

- PARP

poly ADP-ribose polymerase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- DTT

dithiothreitol

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Results from HPLC analysis for compounds 1–42 and the results of Developmental Therapeutic Program at the National Cancer Institute screening against 60 human tumor cell lines with compounds 20 and 22. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Arts HJ, Hollema H, Lemstra W, Willemse PH, De Vries EG, Kampinga HH, Van der Zee AG. Heat-shock-protein-27 (hsp27) expression in ovarian carcinoma: relation in response to chemotherapy and prognosis. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:234–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990621)84:3<234::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrido C, Mehlen P, Fromentin A, Hammann A, Assem M, Arrigo AP, Chauffert B. Inconstant association between 27-kDa heat-shock protein (Hsp27) content and doxorubicin resistance in human colon cancer cells. The doxorubicin-protecting effect of Hsp27. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:653–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0653p.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu HS, Lin JH, Huang WC, Hsu TW, Su K, Chiou SH, Tsai YT, Hung SC. Chemoresistance of lung cancer stemlike cells depends on activation of Hsp27. Cancer. 2011;117:1516–1528. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamada M, So A, Muramaki M, Rocchi P, Beraldi E, Gleave M. Hsp27 knockdown using nucleotide-based therapies inhibit tumor growth and enhance chemotherapy in human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:299–308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrido C, Brunet M, Didelot C, Zermati Y, Schmitt E, Kroemer G. Heat shock proteins 27 and 70: anti-apoptotic proteins with tumorigenic properties. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2592–2601. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.22.3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrido C, Solary E. A role of HSPs in apoptosis through “protein triage”? Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:619–620. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrido C, Bruey JM, Fromentin A, Hammann A, Arrigo AP, Solary E. HSP27 inhibits cytochrome c-dependent activation of procaspase-9. FASEB J. 1999;13:2061–2070. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Concannon CG, Gorman AM, Samali A. On the role of Hsp27 in regulating apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:61–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021601103096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruey JM, Ducasse C, Bonniaud P, Ravagnan L, Susin SA, Diaz-Latoud C, Gurbuxani S, Arrigo AP, Kroemer G, Solary E, Garrido C. Hsp27 negatively regulates cell death by interacting with cytochrome c. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:645–652. doi: 10.1038/35023595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamradt MC, Chen F, Sam S, Cryns VL. The small heat shock protein alpha B-crystallin negatively regulates apoptosis during myogenic differentiation by inhibiting caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38731–38736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandey P, Farber R, Nakazawa A, Kumar S, Bharti A, Nalin C, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D, Kharbanda S. Hsp27 functions as a negative regulator of cytochrome c-dependent activation of procaspase-3. Oncogene. 2000;19:1975–1981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruey JM, Paul C, Fromentin A, Hilpert S, Arrigo AP, Solary E, Garrido C. Differential regulation of HSP27 oligomerization in tumor cells grown in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2000;19:4855–4863. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrido C. Size matters: of the small HSP27 and its large oligomers. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:483–485. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogalla T, Ehrnsperger M, Preville X, Kotlyarov A, Lutsch G, Ducasse C, Paul C, Wieske M, Arrigo AP, Buchner J, Gaestel M. Regulation of Hsp27 oligomerization, chaperone function, and protective activity against oxidative stress/tumor necrosis factor alpha by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18947–18956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Mejia ME, Voss OH, Murnan EJ, Doseff AI. Apigenin-induced apoptosis of leukemia cells is mediated by a bimodal and differentially regulated residue-specific phosphorylation of heat-shock protein-27. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e64. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baylot V, Andrieu C, Katsogiannou M, Taieb D, Garcia S, Giusiano S, Acunzo J, Iovanna J, Gleave M, Garrido C, Rocchi P. OGX-427 inhibits tumor progression and enhances gemcitabine chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e221. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elpek GO, Karaveli S, Simsek T, Keles N, Aksoy NH. Expression of heat-shock proteins hsp27, hsp70 and hsp90 in malignant epithelial tumour of the ovaries. APMIS. 2003;111:523–530. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2003.1110411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang SH, Kang KW, Kim KH, Kwon B, Kim SK, Lee HY, Kong SY, Lee ES, Jang SG, Yoo BC. Upregulated HSP27 in human breast cancer cells reduces herceptin susceptibility by increasing Her2 protein stability. BMC Cancer. 2008;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer R, Ott K, Specht K, Becker K, Lordick F, Burian M, Herrmann K, Schrattenholz A, Cahill MA, Schwaiger M, Hofler H, Wester HJ. Protein expression profiling in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients indicates association of heat-shock protein 27 expression and chemotherapy response. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8279–8287. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherman M, Multhoff G. Heat shock proteins in cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1113:192–201. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinrich JC, Tuukkanen A, Schroeder M, Fahrig T, Fahrig R. RP101 (brivudine) binds to heat shock protein HSP27 (HSPB1) and enhances survival in animals and pancreatic cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1349–1361. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chauhan D, Li G, Shringarpure R, Podar K, Ohtake Y, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Blockade of Hsp27 overcomes Bortezomib/proteasome inhibitor PS-341 resistance in lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6174–6177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong B, Lama R, Smith KM, Xu Y, Su B. Design and synthesis of a biotinylated probe of COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide analog JCC76. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5324–5327. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi X, Zhong B, Smith KM, Geldenhuys WJ, Feng Y, Pink JJ, Dowlati A, Xu Y, Zhou A, Su B. Identification of a class of novel tubulin inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2012;55:3425–3435. doi: 10.1021/jm300100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong B, Cai X, Chennamaneni S, Yi X, Liu L, Pink JJ, Dowlati A, Xu Y, Zhou A, Su B. From COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide to potent anti-cancer agent: synthesis, in vitro, in vivo and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Eur J Med Chem. 2012;47:432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su B, Chen S. Lead optimization of COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide analogs to overcome aromatase inhibitor resistance in breast cancer cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:6733–6735. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.09.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong B, Cai X, Yi X, Zhou A, Chen S, Su B. In vitro and in vivo effects of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor nimesulide analog JCC76 in aromatase inhibitors-insensitive breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;126:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su B, Darby MV, Brueggemeier RW. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel sulfonanilide compounds as antiproliferative agents for breast cancer. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:475–483. doi: 10.1021/cc700138n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faiella L, Piaz FD, Bisio A, Tosco A, De Tommasi N. A chemical proteomics approach reveals Hsp27 as a target for proapoptotic clerodane diterpenes. Mol BioSyst. 2012;8:2637–2644. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25171j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lelj-Garolla B, Mauk AG. Roles of the N- and C-terminal sequences in Hsp27 self-association and chaperone activity. Protein Sci. 2012;21:122–133. doi: 10.1002/pro.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lelj-Garolla B, Mauk AG. Self-association and chaperone activity of Hsp27 are thermally activated. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8169–8174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen B, Su B, Chen S. A COX-2 inhibitor nimesulide analog selectively induces apoptosis in Her2 overexpressing breast cancer cells via cytochrome c dependent mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1787–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang SH, Kang KW, Kim KH, Kwon B, Kim SK, Lee HY, Kong SY, Lee ES, Jang SG, Yoo BC. Upregulated HSP27 in human breast cancer cells reduces herceptin susceptibility by increasing Her2 protein stability. BMC Cancer. 2008;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, Tai LK, Wong LL, Chiu LL, Sethi SK, Koay ES. Proteomic study reveals that proteins involved in metabolic and detoxification pathways are highly expressed in HER-2/neu-positive breast cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1686–1696. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400221-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casado P, Zuazua-Villar P, Prado MA, Valle ED, Iglesias JM, Martinez-Campa C, Lazo PS, Ramos S. Characterization of HSP27 phosphorylation induced by microtubule interfering agents: implication of p38 signalling pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;461:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrieu C, Taieb D, Baylot V, Ettinger S, Soubeyran P, De-Thonel A, Nelson C, Garrido C, So A, Fazli L, Bladou F, Gleave M, Iovanna JL, Rocchi P. Heat shock protein 27 confers resistance to androgen ablation and chemotherapy in prostate cancer cells through eIF4E. Oncogene. 2010;29:1883–1896. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibert B, Eckel B, Fasquelle L, Moulinqq M, Bouhallier F, Gonin V, Mellier G, Simon S, Kretz-Remy C, Arrigo AP, Diaz-Latoud C. Knock down of heat shock protein 27 (HspB1) induces degradation of several putative client proteins. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kindas-Mugge I, Rieder C, Frohlich I, Micksche M, Trautinger F. Characterization of proteins associated with heat shock protein hsp27 in the squamous cell carcinoma cell line A431. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:109–116. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2001.0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma A, Upadhyay AK, Bhat MK. Inhibition of Hsp27 and Hsp40 potentiates 5-fluorouracil and carboplatin mediated cell killing in hepatoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:2106–2113. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.22.9687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song TF, Zhang ZF, Liu L, Yang T, Jiang J, Li P. Small interfering RNA-mediated silencing of heat shock protein 27 (HSP27) increases chemosensitivity to paclitaxel by increasing production of reactive oxygen species in human ovarian cancer cells (HO8910) J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1375–1388. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.