Abstract

Understanding the potential profile of adverse events associated with cancer treatment is essential in balancing safety vs. benefits. Multiple stakeholders make use of this information towards decision-making, including patients, clinicians, researchers, regulators, and payors. Currently, adverse events are reported by clinical research staff, yet evidence suggests that this may contribute to under-reporting of symptom events. Direct patient reporting via electronic interfaces offers a promising mechanism to enhance the efficiency and precision of our current approach, and may complement clinician reports of adverse events. The National Cancer Institute has contracted to develop and test an item bank and software system for directly eliciting adverse symptom event information from patients in cancer clinical research, called the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). The validity, usability, and scalability of the PRO-CTCAE prototype are currently being examined in academic and community-based settings.

Adverse event reporting in the regulatory context

Limitations of drug safety monitoring in both the preapproval and post-market settings are widely acknowledged.1 From an informatics perspective, these limitations are related to the quality of information collected, as well as to processes for efficient collection, aggregation and analysis of these data, and methods of communication to stakeholders -- including patients, clinicians, regulators, and payors.2,3

Information about adverse events in oncology is typically derived from prospective clinical trials conducted in the regulatory setting towards obtaining drug approval, as well as from post-market studies (or in rare cases, case reports or voluntary reporting via mechanisms like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Adverse Event Reporting System [AERS]). Post-market studies may be conducted as part of an industry sponsor's post-market regulatory obligation to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), or may be conducted by independent investigators and organizations outside of this framework (such as in the U.S. National Cancer Institute's [NCI's] cooperative groups).

U.S. drug labels include adverse event information which is largely derived from research conducted by sponsors in the regulatory context, and filtered by sponsors and regulators based on frequency and severity of these events. It is common for oncology drug labels to list 50 to 100 individual adverse reactions, which is comparable to labels in other diseases (Table 1). This number of side effects can be overwhelming to patients trying to determine what experience they are likely to have with a particular treatment.4 In the U.S., drug labels are currently being redesigned, in part due to recognition that greater clarity about adverse reactions is needed.

Table 1.

Adverse Events (AEs) Listed in U.S. Drug Labels

| Indication | # of U.S. Drug Labels | Average # of AEs per Label | Proportion of AEs That Are Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | 35 | 54 | 54% |

| Breast cancer | 32 | 83 | 38% |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 18 | 121 | 47% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 28 | 86 | 46% |

| Osteoarthritis | 39 | 94 | 43% |

Adverse event reporting in comparative effectiveness research

In the largely non-regulated space of comparative effectiveness research (CER), there is even less scrutiny about the precision of adverse event collection and reporting. Despite Institutional Review Board (IRB) oversight and existing mechanisms for monitoring safety data in CER studies which involve patients, standards for how adverse event information is reported both to IRBs and in publications vary widely. Information about product safety derived from CER studies conducted by independent investigators generally is not incorporated into drug labels for the products being evaluated. Therefore, patients, clinicians, and third-party aggregators of clinical information – such as drug information databases, compendia, or developers of systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, and decision-support tools – are left to pool and weight data about safety from disparate sources.

In the context of CER, in which studies are intended to reflect the balance between risks and benefits in real-world populations with patients as the key stakeholders, one would expect even greater attention to be paid to the safety of interventions under evaluation. Moreover, assessment of the comparative tolerability of products is an essential component of CER, and depends on the fidelity of safety reporting. The recent U.S. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act created an independent organization to identify methodological standards in CER, including standards for the measurement and reporting of harms, called the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). An area of focus of PCORI is standardization of the assessment of safety in CER.

Adverse symptom events

About a third of adverse reactions listed in oncology drugs are symptoms (Table 1). Capturing symptom data in clinical trials differs from other types of adverse event data (e.g., laboratory tests) in that it depends on eliciting subjective information from patients. It is acknowledged that the current process in oncology clinical trials for eliciting adverse symptom event information from patients is inadequate.5 Evidence indicates that the validity of reporting symptom outcomes is eroded when those reports are filtered through clinical staff.11 Symptoms experienced by patients are often underestimated by clinical staff members who are responsible for eliciting and reporting this information (both in terms of frequency of occurrence and severity).6 Staff-based adverse event reporting occurs at clinic visits and thus symptoms that occur between visits may be missed.

This presents a challenge from the informatics perspective. In order for an adverse symptom event to be documented in clinical research, the patient must first articulate the problem to a responsible clinical staff member. The staff member will then document that event, generally in a medical chart. This documentation may be on paper or electronic, and generally does not involve use of a standardized valid measurement scale. Subsequently, this information is abstracted by a different staff member and converted to a standardized terminology, such as the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Affairs (MedDRA), or the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). During this process of information flow, the reported experience of the patient may be modified either due to interpretation by the clinical staff member (e.g., “Mrs. Jones doesn't look like she's in that much pain, she says severe, but I suspect it's mild”), or due to the process of mapping the reported experience to the standardized lexicon (“The medical chart says the patient is queezy, that probably means nausea in the CTCAE”).

Adverse event reporting and patient-reported outcomes

Recently, standards for collecting information directly from patients in clinical trials have been consolidated in an FDA Guidance document.7 These standards largely pertain to patient-reported outcomes (PROs) which are intended to result in a labeling claim in the regulatory setting (e.g., improved pain in metastatic prostate cancer), but have also been widely adopted outside of the regulatory setting. The implication of these standards is that symptom experiences of patients should be reported by patients themselves, in order to minimize loss or transformation of this information. The patient knows his or her experience best, and is in the best position to meaningfully report on it, without interpretation or modification by an observer.8

However, the use of PROs has been largely restricted to collection of data to support the efficacy of products, rather than their safety. While it is now common in clinical trials for specific symptoms or health-related quality of life domains to be assessed via patient self-report questionnaires to support assertions of product efficacy or effectiveness, adverse symptom events continue to be elicited, filtered, and reported by clinical staff members.

Direct patient reporting of this information has been proposed as an alternative approach which is more efficient and less prone to data loss, misinterpretation, or transformation.2,5 Patient reporting of symptoms is more reliable and valid than clinician reporting, and is more highly correlated with measures of functional performance and health status than clinician reports.9,10,11 Patient reporting better identifies baseline symptoms related to pre-existing conditions, and patients are willing and able to self-report their own adverse symptom events – even patients with end-stage disease and poor performance status.,9,12

Adverse event reporting and informatics

Despite acknowledged limitations in the assessment of adverse symptom events, there has been substantial progress in the standardization of adverse event reporting in general. MedDRA is a hierarchical lexicon of adverse event terms which was created by an International Conference on Harmonisation, and is maintained across languages by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. MedDRA is universally used in clinical trials in the regulatory context. In oncology specifically, the NCI's CTCAE is the standard item bank used for adverse event reporting. While MedDRA only includes terms for AEs, the CTCAE includes specific criteria for grading the severities of AEs. AE terms used in the CTCAE were recently harmonized with MedDRA in its update to CTCAE version 4. Therefore, almost all cancer clinical trials report adverse events based on the same criteria, the CTCAE, with mapping of these terms to MedDRA.

In clinical trials sponsored by the NCI, two electronic systems have been used for centralized reporting of AE's: the Adverse Event Expedited Reporting System (AdEERS) and Clinical Data Update System (CDUS). Both of these systems require reporting using CTCAE criteria.

Integration of adverse event reporting into electronic clinical trial management systems and electronic medical records is also increasingly common, and in the future will allow for real-time monitoring of adverse events at the patient and group levels. Finally, efforts are underway to improve post-market safety surveillance by linking large databases, such as the FDA's SENTINEL initiative (www.fda.gov/Safety/FDAsSentinelInitiative/ucm2007250.htm).

The overall goal of these efforts is to standardize terminologies and improve the efficiency of reporting and aggregating large amounts of adverse event information by harnessing technology. However, none of them addresses the limitations involved with primary data collection and documentation of patients’ symptoms. Therefore, the information being standardized and aggregated is by its nature insufficient.

The National Cancer Institute's PRO-CTCAE Initiative

Based on recognition of limitations of the current approach to adverse symptom event documentation in cancer trials, in 2008, the NCI contracted for the development of a patient-reported outcomes version of the CTCAE, called the PRO-CTCAE, and an accompanying software platform.13 The scope of this contract, which was awarded to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, includes creating patient questionnaires that assess adverse symptom events; developing an electronic platform for administering these questionnaires to patients via web or telephone (i.e., interactive voice response system [IVRS]) and for reporting the data to clinicians and investigators; testing the measurement properties of PRO-CTCAE questions; and evaluating the feasibility of integrating this approach into multi-center clinical trials.

To date, 124 items representing 78 discrete symptoms in the CTCAE have been developed in English and refined via a cognitive interviewing study in a diverse national sample.14 A multi-site validation study is ongoing in more than 1000 patients,15 as well as a national usability testing evaluation of the software.16 The items have been translated into Spanish and are undergoing linguistic validation; translations into additional languages are underway via Material Transfer Agreements established between the NCI and interested investigators. Moreover, feasibility studies are commencing within multi-center clinical trials in the NCI cooperative groups.

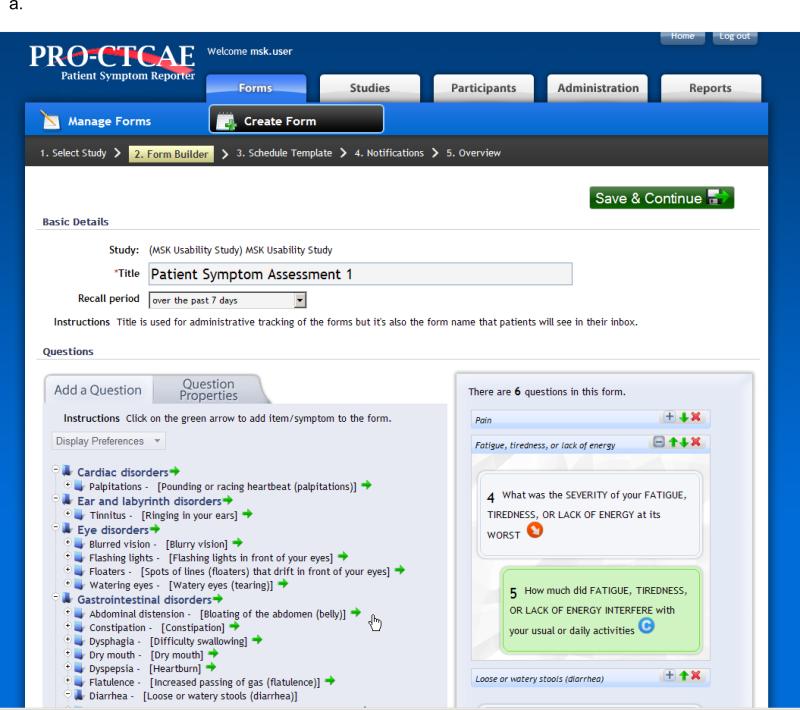

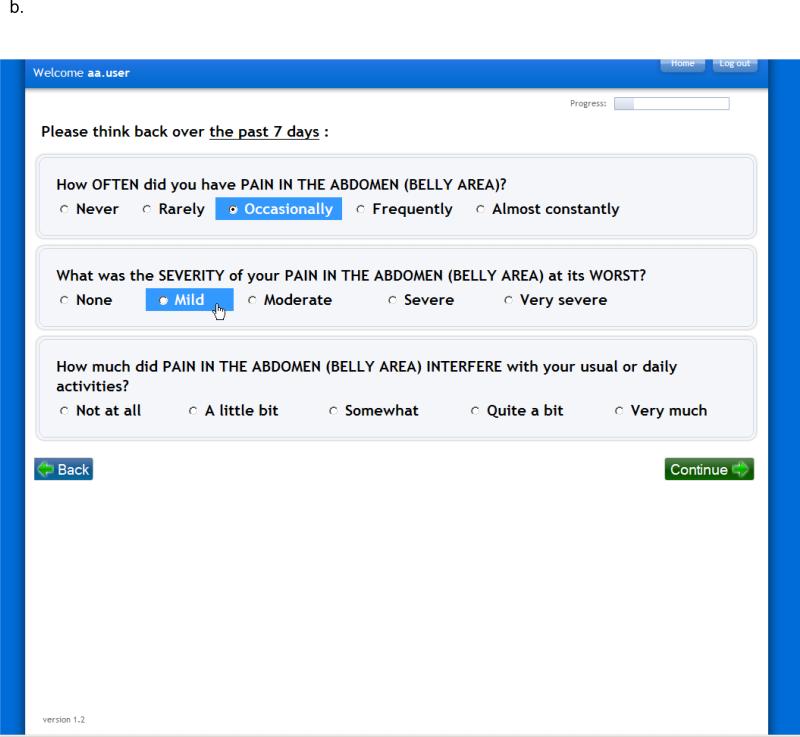

Functionality of the PRO-CTCAE software platform includes the ability for investigators to build and schedule electronic questionnaires for patient self-reporting (Figure 1). Skip patterns to minimize respondent burden are integrated, and the software provides mechanism for patients to report additional symptoms beyond the PRO-CTCAE items, from an existing menu derived from MedDRA, or as free text. Automated alerts are sent to clinical staff for missed reports or symptoms that exceed pre-specified thresholds. Reports can show patient-level or study-level information in standardized graphical formats. The system was designed to be compatible with related software systems supported by the NCI for data capture and adverse event reporting in clinical research.

FIGURE 1.

Screenshots of the PRO-CTCAE Web platform, version 1.0. A, Form builder for research staff to create a PRO-CTCAE form. B, Web interface for patients to complete questions in a form (also available via an automated telephone system).

Conclusion

Electronic patient reporting may improve the quality and comprehensiveness of oncology drug safety information collected in clinical research. The model of reporting that will evolve in the future remains to be determined, but conceivably an approach in which directly reported patient information informs mandatory staff adverse event reporting could emerge. How this information should be used to optimize decision-making and reporting of data in early-phase and phase III trials are areas of active research sponsored by the NCI.

Beyond the clinical trial setting, patient-reported indices of safety and tolerability may play a role in longitudinal registries and safety surveillance systems. Moreover, there is increasing interest to integrate this information into routine cancer care.17 Ultimately, the goal of this work is to develop information systems that allow the patient perspective to be better represented in clinical research, and to develop therapies and care processes which are tailored to patient's preferences and will optimize therapeutic response.

Acknowledgments

Development of the PRO-CTCAE is supported by National Cancer Institute HHSN261201000043C and HHSN261201000063C

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences . The future of drug safety: promoting and protecting the health of the public. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edgerly M, Fojo T. Is there room for improvement in adverse event reporting in the era of targeted therapies? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):240–242. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duke J, et al. “A quantitative analysis of adverse events and ‘overwarning’ in drug labeling”. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):944–946. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Basch E. Patient-Reported Outcomes and the Evolution of Adverse Event Reporting in Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5121–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, et al. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration [June 30, 2011];Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcomes measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Issued December 2009 (available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf)

- 8.Lipscomb J, Reeve BB, Clauser SB, Abrams JS, Bruner DW, Burke LB, Denicoff AM, Ganz PA, Gondek K, Minasian LM, O'Mara AM, Revicki DA, Rock EP, Rowland JH, Sgambati M, Trimble EL. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: taking stock, moving forward. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5133–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, Barz A, Sit L, Fruscione M, Appawu M, Iasonos A, Atkinson T, Goldfarb S, Culkin A, Kris MG, Schrag D. Adverse symptom reporting by patients versus clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, et al. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Roger VL. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(8):530–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meacham R, McEngart D, O'Gorman H, Wenzel K. Use and compliance with electronic patient reported outcomes within clinical drug trials.. Presented at 2008 ISPOR (International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research) Annual International Meeting; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute [June 30, 2011];PRO-CTCAE Wiki Website, Item Development Literature Search Results Page. (available at https://wiki.nci.nih.gov/x/TBGy)

- 14.Hay J, Atkinson TM, Mendoza TR, Reeve BB, Willis G, Gagne JJ, Abernethy AP, Cleeland CS, Schrag D, Basch E. Refinement of the patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE) via cognitive interviewing.. J Clin Oncol; Presented at 2010 ASCO Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. 2010. p. 15s. (suppl; abstr 9060) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Reeve BB, Sloan JA, Cleeland CS, Hay J, Li Y, O'Mara AM, Denicoff A, Basch E. Validation study of the patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE).. J Clin Oncol; Presented at 2010 ASCO Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. 2010. p. 15s. (suppl; abstr TPS274) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal H, Gulati M, Baumgartner P, Coffey D, Kumar V, Chilukuri R, Shouery M, Reeve B, Basch E. Web interface for the patient-reported version of the CTCAE.. NCI caBIG Annual Meeting; Washington, DC. July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basch E, Abernethy AP. Supporting clinical practice decisions with real-time patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(8):954–956. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]