Abstract

The role of non-protein coding RNAs (ncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) in particular, as fine-tuners of both pathological and physiological processes is no longer a matter of debate. With the recent discovery of miRNAs in a wide variety of body fluids and considering them as tools employed in horizontal gene transfer between cells, a new horizon opens in the field of diagnosis and therapeutics. Circulating miRNAs not only enable the communication among cells, but also provide insight into the pathological and physiological state of the originating cells. In this review we summarize the recent advances made in this field, arguing for compelling translation of miRNAs into clinical practice. Moreover, we provide overview of their characteristics and how they impact the evolution of tumor microenvironment and cell-to-cell communication, advancing the idea that miRNAs may function as hormones.

Keywords: miRNAs, therapy, hormones, HGT, nanovesicles, body fluids

1. Introduction

Victor Ambros’s and Garry Ruvkun’s discovery of miRNAs revolutionized research and changed the scientific world’s perspective towards the traditional dogma: DNA → RNA → Protein. Most of the inquiries have been conducted in the cancer field, considering that miRNAs were first linked to this malignancy a decade ago (Calin, et al., 2002). While their reputation as master regulators of almost all biological processes spread rapidly throughout the medical world, it has triggered the interest of scientists working in various fields and as our knowledge about diseases continuously expands, new roles of these small non-coding RNAs have been revealed.

Tumors are no longer being regarded as a collection of relatively homogeneous cancer cells, but rather as a complex assemble of distinct cell types (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2011) in which cell-to-cell communication is essential for the regulation of proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis (M. Hu & Polyak, 2008). Furthermore, if one is to look at cancer through the lens of evolution and ecology, tumor microenvironment can be considered a dynamic ecosystem obeying Darwin’s theory for the selection of the “fittest” cancer cells (Hede, 2009). In this context, horizontal gene transfer (HGT), a mechanism initially described in bacteria for passing of genetic material between organisms, that provides selective advantage in particular environments, emerges as extremely relevant, and various recent studies have advanced the idea that it may occur in multicellular organisms as well (Ahmed & Xiang, 2011; Ratajczak, et al., 2006; Valadi, et al., 2007). HGT through secreted miRNAs is a newly introduced concept aiding the elucidation of cell-to-cell interactions and the mechanisms of co-evolution of tumor cells and their microenvironment. Nevertheless, it is mandatory to point out that here we refer to HGT occurring without genomic integration. Moreover, analyzing miRNAs from this angle grants the means for regarding them as the last addition to the expanding world of hormones.

In this review, we will describe the known characteristics of secreted miRNAs and focus on their impact on the evolution of tumor microenvironment and cell-to-cell communication, highlighting the implications of secreted miRNAs in therapeutics and arguing for their relationship to hormones.

2. What are microRNAs?

The role of non-protein coding RNAs (ncRNAs) as fine-tuners of both pathological and physiological processes is no longer a subject of debate. Findings over the past several years have linked this class of nucleic acids, once considered ‘background noise’, with a large panel of biological processes, such as homeostasis, development and carcinogenesis. MiRNAs are the members of this class that have seized all of the attention since their documented involvement in human diseases.

These small, non-coding RNAs commonly found intracellulary, are 20-23 nucleotides long and expressed in a tissue and developmental specific manner (Ambros, 2003). They can arise from intergenic or intragenic (both exonic and intronic) genomic regions and are transcribed as long primary transcripts (pri-miR), which fold back to form double stranded hairpin structures. Primary transcripts are subjected to sequential processing: first the precursor molecules (pre-miR), 80-120 nucleotides long, are produced in the nucleus by type III endonuclease DROSHA, followed by their export to the cytoplasm mediated by EXPORTIN5, where they are processed by another type III endonuclease, DICER into the short “active” molecules (Kim, 2005).

Commonly, miRNAs negatively regulate gene expression via either mRNA cleavage or translation repression (He & Hannon, 2004), yet it was recently shown that they can upregulate the expression of their target genes as well (Vasudevan, Tong, & Steitz, 2007). Due to the ability of a single miRNA to target hundreds of mRNAs and their involvement in virtually all biological processes, aberrant miRNA expression is associated with the initiation of many diseases, including cancer.

3. Circulating miRNAs

The recent detection of miRNAs in body fluids (e.g. blood, saliva, serum, milk) has led researchers to assign them the intriguing role of gene regulator molecules, in addition to their obvious role as biomarkers (Z. Hu, et al., 2010; Huang, et al., 2010; Mitchell, et al., 2008)

The secretory mechanism remains yet unclear, but three different possibilities have been suggested:

Passive leakage from cells due to injury, chronic inflammation, apoptosis or necrosis, or from cells with short half-lives, such as platelets (Chen, et al., 2008; Mitchell, et al., 2008)

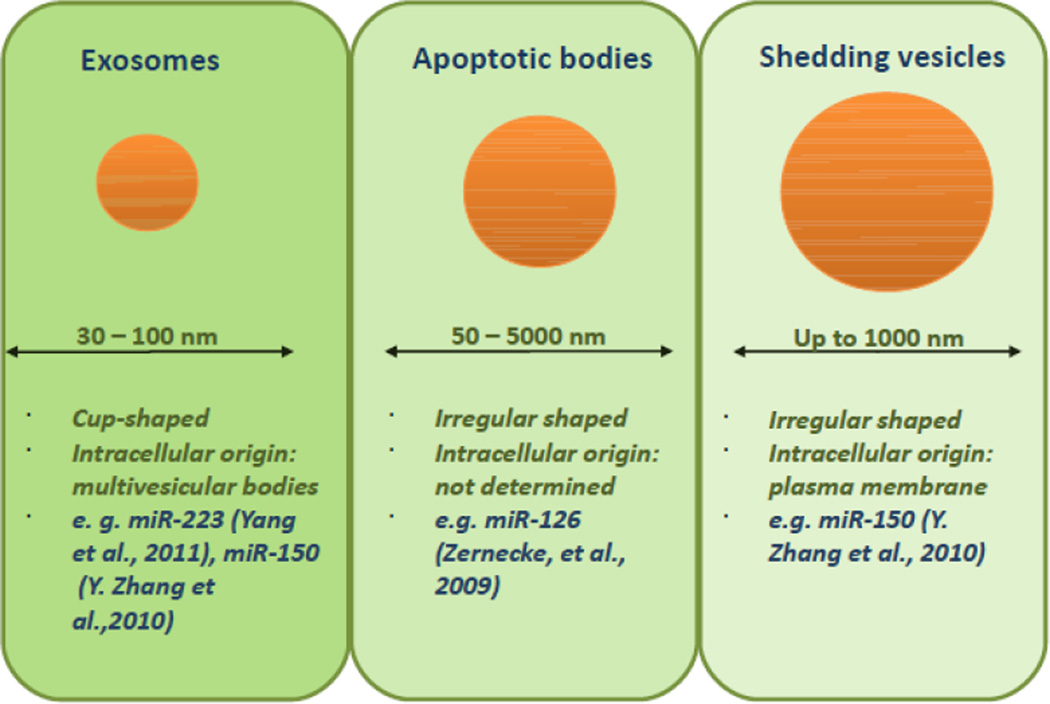

Active secretion via cell-derived membrane vesicles (nanovesicles), including exosomes, shedding vesicles and apoptotic bodies (Valadi, et al., 2007; Zernecke, et al., 2009; Y. Zhang, et al., 2010)

Active secretion by a protein-miRNA complex: studies have shown the association of miRNAs with both lipoproteins (e.g high-density lipoprotein - HDL) and proteins (e.g. Ago2). (Arroyo, et al., 2011; Turchinovich, Weiz, Langheinz, & Burwinkel, 2011; Vickers, Palmisano, Shoucri, Shamburek, & Remaley, 2011)

Many studies have systematically shown the remarkable stability of secretory miRNAs, despite the austere conditions they are subjected to in both the blood stream (RNase digestion) and during handling (e.g. extreme temperatures and pH values) (Boeri, et al., 2011; Chen, et al., 2008).

4. Molecular mechanisms of miRNA transfer

Cell-derived membrane vesicle-mediated transfer

The first evidence of encapsulation of miRNAs into nanovesicles (erroneously called microvesicles, in view of their size) was reported byValadi et al. (2007), who stated that mast cell exosomes containing RNA (mRNA and miRNA) from mouse, are transferred to both human and other murine cells. After this transferral, new murine proteins were found in the recipient cells, demonstrating that exosomal mRNA can be passed into other cells. Thus, it was established that the message delivered on from the donor cells to the neighboring cells via exosomes, does not simply mirror the transcriptional status of the donor cell.

Exosomes are secretory products of endosomal origin with a diameter of 30 to 100 nm (Mathivanan, Ji, & Simpson, 2010; Simons & Raposo, 2009; Thery, Zitvogel, & Amigorena, 2002). They arise when cell membrane proteins transfer to early endosomes by inward budding. Intraluminal vesicles then develop via invagination of the endosomal membrane, generating endosomal carrier vesicles or multivesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs are key players in endolysosomal transport. Exosomes are stored as intraluminal vesicles in MVBs, further being either degraded by fusion of MVBs with lysosomes or released into the extracellular milieu by fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane. The formation of exosomes is facilitated by endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) proteins, which are multiprotein complexes consisting of the vacuolar protein sorting family of proteins (Babst, 2005). An alternative pathway, independent of the ESCRT machinery has also been described, and it includes the ceramide and sphingolipid pathway, in which the enzyme sphingomyelinase-2 (nSMase2) is involved in mediation of exosomal release (Marsh & van Meer, 2008; Trajkovic, et al., 2008). Exosomes are released by a wide spectrum of cell types (e.g. monocytes, B cells, T cells, mast cells, epithelial cells), however their secretion is constitutive and exacerbated in cancer cells, and it appears to be modulated by microenvironmental milieu, influenced for instance by growth factors, heat shock and stress conditions, pH variations and therapy (Ciravolo, et al., 2012; Hedlund, Nagaeva, Kargl, Baranov, & Mincheva-Nilsson, 2011; Khan, et al., 2011; Parolini, et al., 2009).

Shedding vesicles share properties with classical vesicles, although they are more heterogeneous in shape and larger (up to 1000 nm) than exosomes (Cocucci, Racchetti, & Meldolesi, 2009; Cocucci, Racchetti, Podini, & Meldolesi, 2007; Mathivanan, et al., 2010)(Figure 1). They are released by cells, both at rest and upon stimulation, via outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane and thus can be molecularly different. The shedding vesicles of tumor cells and neutrophils are enriched with metalloproteinase as well as other proteolytic enzymes used for the digestion of the extracellular matrix, necessary for the progress of inflammation and tumor growth (Gasser, et al., 2003; Giusti, et al., 2008; Mochizuki & Okada, 2007). Analogous to exosomes, shedding vesicles are dispensed by a broad range of cells, usually mixed with exosomes (Cocucci, et al., 2009) and the delivery of their content seems to be facilitated through receptor-ligand interaction.

Figure 1. Types of vesicles as miRNAs “shuttles”.

The main characteristics and some examples of miRNAs proved to be transported are presented.

Other studies followed to confirm and extend to the discovery by Valadi and colleagues. For example Hunter et al. (Hunter, et al., 2008) identified and defined the profile of exosome-encapsulated miRNAs circulating in the plasma of healthy individuals. Additionally, they found that 37 miRNAs were expressed at significantly different levels between plasma nanovesicles and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and that the majority of these miRNAs were predicted to regulate cellular differentiation of blood cells and metabolic pathways. Another study determined that nanovesicles originated from human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and liver resident stem cells containing selective patterns of expression of miRNAs, that could be transferred to target cells, where they downregulated their well-established targets (Collino, et al., 2010). Relating this finding to an earlier observation by Kaplan and colleagues, that certain tumors induce the mobilization of bone-marrow derived endothelial progenitors to form a “premetastatic niche” by modulating the tumor microenvironment, one can conclude that miRNAs are the tools employed in this process (Kaplan, et al., 2005). In agreement with this hypothesis, a recent study showed that macrophage regulate the invasiveness of breast cancer cells through exosome-mediated delivery of oncogenic miRNAs. To verify miRNA transport between IL4 activated-macrophages and breast cancer cells, researchers transfected Cy3-labeled miR-223 into macrophages and tracked its movement (Yang, et al., 2011). Thus, the authors proposed a plausible mechanism of promoting breast cancer invasion through the miR-223/Mef2c/β-catenin pathway.

Zhang et al. (Y. Zhang, et al., 2010) reported on the delivery of THP-1-derived nanovesicles containing miR-150 into HMEC-1 cells, resulting in elevated levels of this miRNA. Moreover, exogenous miR-150 effectively reduced the expression of c-Myb, a traditional target of the miRNA, and enhanced migration in the recipient cells. Similar, Kosaka et al. (Kosaka, Iguchi, et al., 2010) showed that re-expression of the tumor-suppressor miR-146 via intercellular transfer leads to cell growth inhibition in PC-3M cells.

Considering that nanovesicles are dispensed by a vast array of cells, the discovery of antigen-dependent, unidirectional intercellular transfer of miRNAs by exosomes during immune synapses was not surprising. The importance of exosome release in this process was demonstrated by the correlation of miRNA transfer with that of CD63 and by its’ blockade with inhibitors of exosome production (Mittelbrunn, et al., 2011). The research group also noticed that targeting nSMase2 impairs the transfer of miRNAs to APCs (antigen-presenting cells), an observation consistent with a study by Kosaka et al. (Kosaka, Izumi, Sekine, & Ochiya, 2010).

Recently, Montecalvo et al. (Montecalvo, et al., 2012) demonstrated that murine dendritic cells (DCs) release exosomes with diverse patterns of miRNA loading, depending on the maturity level of the DCs and suggested that interactions among DCs may be mediated by these exosome-shuttled miRNAs. The miRNA clusters identified in exosomes, such as miR-34a and miR-21, which are involved in differentiation of hematopoietic precursors into myeloid DCs, or miR-146a, miR-125-5p and miR-148, all negative regulators of pro-inflammatory transcripts in myeloid cells and DCs, support this hypothesis.

In addition, investigators detected Epstein Barr virus (EBV) BART miRNAs in exosomes exempted by EBV-infected B-cells (Pegtel, et al., 2010) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells (Gourzones, et al., 2010).

Apoptotic bodies are small membranous vesicles (diameter 50 to 5000 nm) formed after the induction of apoptosis. During apoptosis, cells can either shrink and then fragment into apoptotic bodies- or completely transform into these bodies (Majno & Joris, 1995). Endothelial cell–derived apoptotic bodies are generated during atherosclerosis and convey paracrine alarm signals to recipient vascular cells to trigger tissue repair and angiogenesis by cytokine and growth factor secretion. Zernecke et al (Zernecke, et al., 2009), showed that CXCL12 production is mediated by miR-126, which was enriched in the apoptotic bodies and repressed the function of regulator of G protein signaling 16 (RGS16), an inhibitor of G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling. This enabled CXCR4, a CXCL12 receptor, to activate an autoregulatory feed-back loop. In agreement with this protective role of miR-126 in experimental models of atherosclerosis, miR-126 plasma levels were found to be decreased in patients with coronary atherosclerosis (Fichtlscherer, et al., 2010).

Moreover, Zampetaki et al. (Zampetaki, et al., 2010) observed that loss of miR-126 expression was consistently associated with type 2 diabetes and that the miR-126 content in endothelial apoptotic bodies decreased in a glucose-dependent manner. They suggested that low plasma levels of miR-126 result in reduced delivery of this miRNA to monocytes and contribute to VEGF resistance and endothelial dysfunction.

The reasons for the presence of miRNAs in nanovesicles and the manner in which they are sorted for incorporation have yet to be unveiled. Components of the RNA-induced silencing complex such as the proteins GW182 and Argonaute2, mRNAs, and mature miRNAs are associated with MVBs and exosomes, suggesting that MVBs are sites of assembly of the miRNA-silencing machinery and/or sorting of miRNAs into exosomes (Gibbings, Ciaudo, Erhardt, & Voinnet, 2009).

Non-cell-derived membrane vesicle-mediated transfer

Recent studies demonstrated that miRNAs can be delivered by mechanisms other than nanovesicle secretion. One such mechanism is by HDL-transport. Vickers et al. (Vickers, et al., 2011) reported the presence of miRNAs bound to HDLs in the plasma of healthy subjects and showed that nSMase2 and probably the ceramide signaling pathway repressed the cellular export of miRNAs. As overexpression of nSMase2 and activation of the ceramide signaling pathway have been established to induce nanovesicle release from cells and engage cellular export of miRNAs, the export via the HDL pathway may be distinct and occur through opposing mechanisms. Uptake of cholesteryl ester from HDL by the recipient cell seems to be dependent on the cell surface HDL receptor, named scavenger receptor class B, type I (SRBI).

However, novel findings suggest that the majority of circulating miRNAs may not be associated with or confined within nanovesicles, but rather are bound to protein complexes, such as Argonaute-2 (Ago2) (Arroyo, et al., 2011; Turchinovich, et al., 2011) and nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) (Wang, Zhang, Weber, Baxter, & Galas, 2010). These findings raise indeed intriguing questions about whether these miRNAs have a different biological role and source; researchers have proposed that miRNA-protein complexes may be released into circulation as a consequence of cell lysis or necrosis, without participating in intercellular communication. Nonetheless, we believe that these complexes have a defined, but yet to be discovered role.

5. MiRNAs – thinking outside the box

The process of cancer initiation and progression is a dynamic one involving a complex signaling network of tumor cells and their microenvironment. It was once pointed out that tumors are ecosystems in which cancer cells interact with normal host cells as well as growth factors, oxygen, and other resources and factors in their environment (Hede, 2009). Combining these two concepts, we hypothesize that circulating miRNAs are among the essential players in the evolution of tumor microenvironment which influences tumor progression by mediating intercellular communication. Several studies have demonstrated significant differences in the miRNA profile of normal and tumor derived exosomes (Gourzones, et al., 2010; Ohshima, et al., 2010; Rabinowits, Gercel-Taylor, Day, Taylor, & Kloecker, 2009; Skog, et al., 2008; Taylor & Gercel-Taylor, 2008) supporting our hypothesis. Moreover, it was recently reported that exogenous plant miRNAs are present in the sera and tissues of various animals and that they are mainly acquired through food intake. Surprisingly, plant miR-168a could not only be transferred from human small intestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2) to human hepatocytes (HepG2) via exosomes, but it could also bind to the human/mouse low-density lipoprotein receptor adaptor protein 1 (LDLRAP1) and consequentially decrease LDL levels (L. Zhang, et al., 2012); a classical example of HGT. Per se, miRNAs can be regarded as hormones, a view opening a new venue in cell-interaction research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of microRNAs involved in cell-to-cell communication

| miRNA | Cell to cell | Target | Clinical and therapeutic significance |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-126 | Endothelial cells to vascular cells | RGS16 | Activation of tissue repair and angiogenesis | (Zernecke, et al., 2009) |

| miR-146a (plant) | Rice plant cells to small intestinal epithelial cells to human hepatoma cells | LDLRAP1 | Decreased levels of LDL (low-density lipoprotein) | (L. Zhang, et al., 2012) |

| miR-150 | Monocytic leukemia cells to HMEC-1 cells | c-Myb | Promote cell migration | (Y. Zhang, et al., 2010) |

| miR-223 | Tumor-associated macrophages to breast cancer cells (SKBR3, MDA-MB-231) | The Mef/β-catenin pathway | Regulation of invasiveness of breast cancer cells | (Yang, et al., 2011) |

| EBV-miRNAs (BARTs) | EBV—positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to endothelial cells (HUVECs) | CXCL11 and LMP1 | Repression of immunostimulatory genes | (Pegtel, et al., 2010) |

Because miRNAs are known to regulate the expression of hundreds of target mRNAs, thereby modulating a large number of processes, some of which are described above (e.g. angiogenesis, apoptosis, tumor growth) profiling these circulating, small non-coding RNAs would provide insight into the molecular changes in cells they are derived from and, hence, provide diagnostic information and aid in therapeutic decisions making to ensure the best care for patients.

Furthermore, miRNAs identified in placenta-derived exosomes (Mincheva-Nilsson & Baranov, 2010) and breast milk (Zhou, et al., 2012) function as immune regulators in fetalmaternal crosstalk, not only during pregnancy, when they improve maternal adaptation to present physiological state and promote fetal allograft survival, but also after birth, presumably transferring genetic material from the mother to the infant, which is critical for development of the infant’s immune system. Additionally, in a recent study, researchers attributed cell communication within the ovarian follicle, which is critical for the growth and maturation of a healthy oocyte that can be fertilized and develop into an embryo, to microvesicles containing miRNAs (da Silveira, Veeramachaneni, Winger, Carnevale, & Bouma, 2012). The miRNAs present in exosomes in ovarian follicular fluid varied with the age of the mare, and a number of different miRNAs were detected in young versus old mare follicular fluid. These findings advanced the idea that the miRNA profiles in body fluids mirror both pathological and physiological conditions.

6. Therapeutic implications of miRNAs as hormones

The diagnostic and therapeutic potentials of circulating miRNAs have long been acknowledged, with various studies vouching for their use as predictors of sensitivity to radiotherapy or anticancer agents, or as biomarkers for monitoring disease evolution during treatment (Jung, et al., 2012; Weiss, et al., 2008). Yet research has not found the means to transpose them into clinic, partly because of the conflicting data presented by most profiling studies. Some of the challenges encountered when profiling miRNAs in body fluids are likely due to different methodologies, to diverse reference genes used for normalization or differences in blood collection (Peltier & Latham, 2008). Intensive efforts to overcome these challenges have been made such as employing synthetic versions of miRNAs from other organisms as normalizers (Mitchell, et al., 2008) or introducing standardized protocols for specimen collection and processing.

A different approach would be to focus on specific miRNAs based on strong pathogenic models of diseases. A fine example is murine models based on miRNA knock-down or overexpression. In Table 2 we summarize several of these models, bringing to notice that a few of the circulating miRNAs have already been the focus of these studies (Fichtlscherer, et al., 2010; Hunter, et al., 2008; Montecalvo, et al., 2012).

Table 2.

Examples of translating leukemia murine models into clinical practice

| MiRNA | Type of expression variation |

Biological function/mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-15a/16-1 | Transplantation, overexpression | Inhibit leukemia cells growth | (Calin, et al., 2008) |

| miR-16 | Mutation in New Zealand of CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia) | Delivery of exogenous miR-16 to the NZB malignant B-1 cell line resulted in cell-cycle alterations, including a decrease in cells in S phase and G1 arrest | (Scaglione, et al., 2007) |

| miR-17~19b | Transplantation, overexpression | Accelerates MLL-mediated leukemia | (Lawson, et al., 2010) |

| miR-19b, miR-20a, miR-26a, miR-92 and miR-223 | Transplantation, over expression | T-ALL in NOTCH1-ICN - induced mice | (Mavrakis, et al., 2011) |

| miR-29b | Transplantation, over expression | Inhibits AML leukemic growth in vivo, in K562 cells transplanted mice | (Garzon, et al., 2009) |

| miR-124a | Transplantation, over expression | Up-regulation of miR-124a expression decreases ALL cell growth in TOM-1 transplanted mice | (Agirre, et al., 2009) |

| miR-125b | Transplantation, over expression | Accelerates the development of BCR-ABL – induced leukemia in mice (B-ALL, T-ALL) | (Bousquet, Harris, Zhou, & Lodish, 2010) |

| miR-150 | Transplantation, knock down | Increases number of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells by using mouse acute myocardial infarction model | (Tano, Kim, & Ashraf, 2011) |

| miR-155 | Knock in | Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia, high-grade lymphoma | (Costinean, et al., 2006) |

| miR-451, miR-709 | Transplantion, over expression | Notch1-driven leukemogenesis | (Li, Sanda, Look, Novina, & von Boehmer, 2011) |

Abbreviations: AML (acute myelogenous leukemia); B-ALL (B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia); MLL-mediated leukemia (mixed lineage leukemia); T-ALL (T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia);

Overall, implementing miRNAs into clinical practice holds several advantages, as isolation of nanovesicles is non-invasive and the signatures of secretory miRNA are remarkably similar to those of the cells they derived from.

7. Conclusion

Our knowledge about extracellular miRNAs is at the germinal state. We still have a great deal to learn about how miRNAs are sorted for secretion or recognized by different complexes for uptake, but most importantly what their function is. Answers to these questions will enable us to make full use of the complete potential of the “liquid biopsy” provided by the miRNAs, allowing physicians to observe changes in the physiological condition over time and tailor treatment modalities.

Acknowledgements

Dr Calin is The Alan M. Gewirtz Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar. He is supported also as a Fellow at The University of Texas MD Anderson Research Trust, as a University of Texas System Regents Research Scholar and by the CLL Global Research Foundation. Work in Dr. Calin’s laboratory is supported in part by the NIH/NCI, a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Idea Award, Developmental Research Awards in Breast Cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Brain Cancer, Prostate, Multiple Myeloma and Leukemia SPOREs, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the RGK Foundation and the Estate of C. G. Johnson, Jr. We thank Donald Norwood, ELS, Department of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for expert editorial assistance.

Work in Dr. MJ You’s laboratory is supported in part by NIH/NCI, Ladies Leukemia League, American Cancer Society IRG, Developmental Research Awards in Leukemia SPORE, and Center for Inflammation and Cancer, IRG and Physician Scientist Award of UT MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- miRNA

microRNA

- HGT

horizontal gene transfer

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- MVB

multivesicular body

- nSMase2

sphingomyelinase-2

- DC

dentritic cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agirre X, Vilas-Zornoza A, Jimenez-Velasco A, Martin-Subero JI, Cordeu L, Garate L, San Jose-Eneriz E, Abizanda G, Rodriguez-Otero P, Fortes P, Rifon J, Bandres E, Calasanz MJ, Martin V, Heiniger A, Torres A, Siebert R, Roman-Gomez J, Prosper F. Epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor microRNA Hsa-miR-124a regulates CDK6 expression and confers a poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4443–4453. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed KA, Xiang J. Mechanisms of cellular communication through intercellular protein transfer. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1458–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, Tait JF, Tewari M. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M. A protein's final ESCRT. Traffic. 2005;6:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri M, Verri C, Conte D, Roz L, Modena P, Facchinetti F, Calabro E, Croce CM, Pastorino U, Sozzi G. MicroRNA signatures in tissues and plasma predict development and prognosis of computed tomography detected lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3713–3718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100048108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet M, Harris MH, Zhou B, Lodish HF. MicroRNA miR-125b causes leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21558–21563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin GA, Cimmino A, Fabbri M, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Shimizu M, Taccioli C, Zanesi N, Garzon R, Aqeilan RI, Alder H, Volinia S, Rassenti L, Liu X, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. MiR-15a and miR-16-1 cluster functions in human leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5166–5171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800121105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, Rassenti L, Kipps T, Negrini M, Bullrich F, Croce CM. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, Guo J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Guo X, Li Q, Li X, Wang W, Wang J, Jiang X, Xiang Y, Xu C, Zheng P, Zhang J, Li R, Zhang H, Shang X, Gong T, Ning G, Zen K, Zhang CY. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18:997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciravolo V, Huber V, Ghedini GC, Venturelli E, Bianchi F, Campiglio M, Morelli D, Villa A, Della Mina P, Menard S, Filipazzi P, Rivoltini L, Tagliabue E, Pupa SM. Potential role of HER2-overexpressing exosomes in countering trastuzumab-based therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:658–667. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Podini P, Meldolesi J. Enlargeosome traffic: exocytosis triggered by various signals is followed by endocytosis, membrane shedding or both. Traffic. 2007;8:742–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collino F, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Sterpone L, Aghemo G, Viltono L, Tetta C, Camussi G. Microvesicles derived from adult human bone marrow and tissue specific mesenchymal stem cells shuttle selected pattern of miRNAs. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costinean S, Zanesi N, Pekarsky Y, Tili E, Volinia S, Heerema N, Croce CM. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7024–7029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602266103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira JC, Veeramachaneni DN, Winger QA, Carnevale EM, Bouma GJ. cell-secreted vesicles in equine ovarian follicular fluid contain miRNAs and proteins: a possible new form of cell communication within the ovarian follicle. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:71. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtlscherer S, De Rosa S, Fox H, Schwietz T, Fischer A, Liebetrau C, Weber M, Hamm CW, Roxe T, Muller-Ardogan M, Bonauer A, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Circulating microRNAs in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2010;107:677–684. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R, Heaphy CE, Havelange V, Fabbri M, Volinia S, Tsao T, Zanesi N, Kornblau SM, Marcucci G, Calin GA, Andreeff M, Croce CM. MicroRNA 29b functions in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:5331–5341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser O, Hess C, Miot S, Deon C, Sanchez JC, Schifferli JA. Characterisation and properties of ectosomes released by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbings DJ, Ciaudo C, Erhardt M, Voinnet O. Multivesicular bodies associate with components of miRNA effector complexes and modulate miRNA activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1143–1149. doi: 10.1038/ncb1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti I, D'Ascenzo S, Millimaggi D, Taraboletti G, Carta G, Franceschini N, Pavan A, Dolo V. Cathepsin B mediates the pH-dependent proinvasive activity of tumor-shed microvesicles. Neoplasia. 2008;10:481–488. doi: 10.1593/neo.08178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourzones C, Gelin A, Bombik I, Klibi J, Verillaud B, Guigay J, Lang P, Temam S, Schneider V, Amiel C, Baconnais S, Jimenez AS, Busson P. Extra-cellular release and blood diffusion of BART viral micro-RNAs produced by EBV-infected nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Virol J. 2010;7:271. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hede K. Looking at cancer through an evolutionary lens. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1108–1109. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund M, Nagaeva O, Kargl D, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L. Thermal- and oxidative stress causes enhanced release of NKG2D ligand-bearing immunosuppressive exosomes in leukemia/lymphoma T and B cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Polyak K. Molecular characterisation of the tumour microenvironment in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2760–2765. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Chen X, Zhao Y, Tian T, Jin G, Shu Y, Chen Y, Xu L, Zen K, Zhang C, Shen H. Serum microRNA signatures identified in a genome-wide serum microRNA expression profiling predict survival of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1721–1726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Huang D, Ni S, Peng Z, Sheng W, Du X. Plasma microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for early detection of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:118–126. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter MP, Ismail N, Zhang X, Aguda BD, Lee EJ, Yu L, Xiao T, Schafer J, Lee ML, Schmittgen TD, Nana-Sinkam SP, Jarjoura D, Marsh CB. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung EJ, Santarpia L, Kim J, Esteva FJ, Moretti E, Buzdar AU, Di Leo A, Le XF, Bast RC, Jr, Park ST, Pusztai L, Calin GA. Plasma microRNA 210 levels correlate with sensitivity to trastuzumab and tumor presence in breast cancer patients. Cancer. 2012;118:2603–2614. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Jutzy JM, Aspe JR, McGregor DW, Neidigh JW, Wall NR. Survivin is released from cancer cells via exosomes. Apoptosis. 2011;16:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0534-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:376–385. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17442–17452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N, Izumi H, Sekine K, Ochiya T. microRNA as a new immune-regulatory agent in breast milk. Silence. 2010;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JS, Glenn WK, Salmons B, Ye Y, Heng B, Moody P, Johal H, Rawlinson WD, Delprado W, Lutze-Mann L, Whitaker NJ. Mouse mammary tumor virus-like sequences in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3576–3585. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Sanda T, Look AT, Novina CD, von Boehmer H. Repression of tumor suppressor miR-451 is essential for NOTCH1-induced oncogenesis in T-ALL. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011;208:663–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majno G, Joris I. Apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis. An overview of cell death. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh M, van Meer G. Cell biology. No ESCRTs for exosomes. Science. 2008;319:1191–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1155750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1907–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrakis KJ, Van Der Meulen J, Wolfe AL, Liu X, Mets E, Taghon T, Khan AA, Setty M, Rondou P, Vandenberghe P, Delabesse E, Benoit Y, Socci NB, Leslie CS, Van Vlierberghe P, Speleman F, Wendel HG. A cooperative microRNA-tumor suppressor gene network in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) Nat Genet. 2011;43:673–678. doi: 10.1038/ng.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincheva-Nilsson L, Baranov V. The role of placental exosomes in reproduction. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:520–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O'Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelbrunn M, Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, Gonzalez S, Sanchez-Cabo F, Gonzalez MA, Bernad A, Sanchez-Madrid F. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Commun. 2011;2:282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki S, Okada Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan ML, Karlsson JM, Baty CJ, Gibson GA, Erdos G, Wang Z, Milosevic J, Tkacheva OA, Divito SJ, Jordan R, Lyons-Weiler J, Watkins SC, Morelli AE. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119:756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima K, Inoue K, Fujiwara A, Hatakeyama K, Kanto K, Watanabe Y, Muramatsu K, Fukuda Y, Ogura S, Yamaguchi K, Mochizuki T. Let-7 microRNA family is selectively secreted into the extracellular environment via exosomes in a metastatic gastric cancer cell line. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L, Palleschi S, De Milito A, Coscia C, Iessi E, Logozzi M, Molinari A, Colone M, Tatti M, Sargiacomo M, Fais S. Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34211–34222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL, de Gruijl TD, Wurdinger T, Middeldorp JM. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6328–6333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier HJ, Latham GJ. Normalization of microRNA expression levels in quantitative RTPCR assays: identification of suitable reference RNA targets in normal and cancerous human solid tissues. RNA. 2008;14:844–852. doi: 10.1261/rna.939908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowits G, Gercel-Taylor C, Day JM, Taylor DD, Kloecker GH. Exosomal microRNA: a diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:42–46. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, Zhang J, Reca R, Dvorak P, Ratajczak MZ. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20:847–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglione BJ, Salerno E, Balan M, Coffman F, Landgraf P, Abbasi F, Kotenko S, Marti GE, Raveche ES. Murine models of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: role of microRNA-16 in the New Zealand Black mouse model. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:645–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Raposo G. Exosomes--vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skog J, Wurdinger T, van Rijn S, Meijer DH, Gainche L, Sena-Esteves M, Curry WT, Jr, Carter BS, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1470–1476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tano N, Kim HW, Ashraf M. microRNA-150 regulates mobilization and migration of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells by targeting Cxcr4. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7223–7233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:423–433. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Zhang S, Weber J, Baxter D, Galas DJ. Export of microRNAs and microRNAprotective protein by mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7248–7259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss GJ, Bemis LT, Nakajima E, Sugita M, Birks DK, Robinson WA, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, Haney J, Helfrich BA, Kato H, Hirsch FR, Franklin WA. EGFR regulation by microRNA in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response and survival to gefitinib and EGFR expression in cell lines. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1053–1059. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Chen J, Su F, Yu B, Lin L, Liu Y, Huang JD, Song E. Microvesicles secreted by macrophages shuttle invasion-potentiating microRNAs into breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:117. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampetaki A, Kiechl S, Drozdov I, Willeit P, Mayr U, Prokopi M, Mayr A, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Bonora E, Shah A, Willeit J, Mayr M. Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107:810–817. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Koppel T, Jahantigh MN, Lutgens E, Wang S, Olson EN, Schober A, Weber C. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Hou D, Chen X, Li D, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Li J, Bian Z, Liang X, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang C, Zhang T, Zhu D, Zhang D, Xu J, Chen Q, Ba Y, Liu J, Wang Q, Chen J, Wang J, Wang M, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY. Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. Cell Res. 2012;22:107–126. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu D, Chen X, Li J, Li L, Bian Z, Sun F, Lu J, Yin Y, Cai X, Sun Q, Wang K, Ba Y, Wang Q, Wang D, Yang J, Liu P, Xu T, Yan Q, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY. Secreted monocytic miR-150 enhances targeted endothelial cell migration. Mol Cell. 2010;39:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Li M, Wang X, Li Q, Wang T, Zhu Q, Zhou X, Gao X, Li X. Immunerelated microRNAs are abundant in breast milk exosomes. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:118–123. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]