Abstract

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) have emerged as a major cause of morbidity and mortality among critically ill patients. Cancer patients admitted in the intensive care unit (ICU) have multiple risk factors for IFIs. The vast majority of IFIs in the ICU are due to Candida spp. The incidence of invasive candidiasis (IC) has increased over the last decades, especially in the ICU. A shift in the distribution of Candida spp. from Candida albicans to non-albicans Candida spp. has been observed both in ICUs and oncology units in the last two decades. Timely diagnosis of IC remains a challenge despite the introduction of new microbiology techniques. Delayed initiation of antifungal therapy is associated with increased mortality. Therefore, prediction rules have been developed and validated prospectively in order to identify those ICU patients at high risk for IC and likely to benefit from early treatment. These rules, however, have not been validated in cancer patients. Similarly, major clinical studies on the efficacy of newer antifungals typically do not include cancer patients. Despite the introduction of more potent and less toxic antifungals, mortality of IFIs among cancer patients remains high. In recent years, aspergillosis and mucormycosis have also emerged as significant causes of morbidity and mortality among ICU patients with haematological cancer.

Keywords: Fungal infections, Cancer patients, Intensive care unit

1. Introduction

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) represent a major cause of increased morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients. Furthermore, patients with cancer in intensive care units (ICUs) are particularly vulnerable to invasive mycoses because they typically have multiple, interrelated risk factors for these infections [1]. Candida yeasts and Aspergillus moulds are the main causes of IFIs in the ICU. Here we summarise our current understanding of the epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and outcome in this especially vulnerable population.

2. Candidiasis

2.1. Epidemiology of and risk factors for invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients with cancer

Candida spp. represent the fourth most prevalent pathogen isolated from blood cultures or deep-site infections in US hospitals [2] as well as in much of the developed world, causing 8–15% of all bloodstream infections (BSIs) [2–5]. It should be noted that invasive candidiasis (IC) can occur without candidaemia; in a recent multicentre study in French ICUs, 32% of patients had IC without documented candidaemia [3]. The overall incidence of both candidaemia and IC has increased over the past two decades, with the highest incidences encountered in ICUs [3,6]. The recent Extended Prevalence of Infection in the ICU (EPIC II) study, conducted in 1265 ICUs in 76 countries, showed that of the 14 414 enrolled patients, 99 had Candida BSIs, giving a prevalence of 6.9 per 1000 patients [5]. This increase reflects advances in supportive care and the resulting increased survival rates in high-risk patients susceptible to this infection.

Risk factors for IC in ICU patients (Table 1) include: prior use of broad-spectrum antibiotics; placement of central venous catheters (CVCs); receipt of total parenteral nutrition (TPN); advanced age; diabetes mellitus; use of immunosuppressive agents, including corticosteroids; use of gastric acid suppressants; prior abdominal surgery, especially when complicated by gastrointestinal tract perforations and anastomotic leaks; advanced underlying illness; Candida spp. colonisation, especially when isolated from multiple mucosal sites; and length of ICU stay >7 days [1,3,7,8]. ICU patients with cancer have additional risk factors for candidaemia, such as chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and/or mucositis, systemic corticosteroids, radiation-induced tissue injury, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and/or graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and infiltrating tumours that disrupt mucosal integrity [9,10]. In the EPIC II study, patients with candidaemia were more likely to have solid tumours than patients with Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacterial BSIs [5].

Table 1.

Risk factors for invasive fungal infections in intensive care unit (ICU) cancer patients and the implicated pathogenetic mechanisms

| Risk factor | Pathogenetic mechanism |

|---|---|

| Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics | Elimination of normal bacterial flora → fungal colonisation |

| Direct vascular access | |

| Central venous catheters | Direct vascular access |

| Fungal colonisation of plastic lumen surfaces | |

| Nasogastric tubes and/or use of gastric acid suppressants | Suppression of local gastric immune mechanisms |

| Diabetes mellitus | Immunosuppression |

| Total parenteral nutrition | Direct vascular access |

| Contaminated vial content | |

| ICU stay | Candida colonisation |

| Intubation → abolition of local defence mechanism of lungs | |

| Abdominal surgery | Disruption of anatomical barriers |

| Translocation of fungi into the bloodstream | |

| Chemotherapy/radiation therapy | Immunosuppression, especially of cellular immunity |

| Gastrointestinal mucositis → disruption of anatomical barriers → fungal translocation | |

| Corticosteroids/immunosuppressive agents | Suppression of the immune system, especially the cellular component |

| HSCT with or without GvHD | Heavy immunosuppression |

| Mucositis | |

| Disruption of anatomical barriers | |

| Elderly | Immunosuppression |

| Co-morbidities |

HSCT, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; GvHD, graft-versus-host disease.

In the last two decades, the major epidemiological trend regarding IC in ICUs and oncology units has been the shift in the distribution of offending Candida spp. from Candida albicans to non-albicans Candida spp. such as Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei and Candida parapsilosis [9–11]. Risk factors for IC caused by non-albicans Candida spp. in the ICU include prior fluconazole use, prior use of broad-spectrum antibacterials [12], history of gastrointestinal surgery and placement of CVCs [1,9,13,14].

Adoption of azole-based prophylaxis in many ICUs has resulted in increasing incidences of breakthrough candidaemias, typically owing to non-albicans Candida spp. such as C. glabrata and C. krusei [1]. In patients receiving echinocandins, the incidence of breakthrough catheter-related candidaemia caused by C. parapsilosis has increased [9]. In a recent, prospective, multicentre surveillance study of Candida BSIs in 2441 patients in France, decreased in vitro susceptibility to fluconazole or caspofungin was associated with prior use of the respective antifungal agent [15]. In addition, breakthrough IC occurs more often in patients with haematological malignancies and chemotherapy-induced neutropenia [10].

2.2. Prediction rules for invasive candidiasis in intensive care unit patients

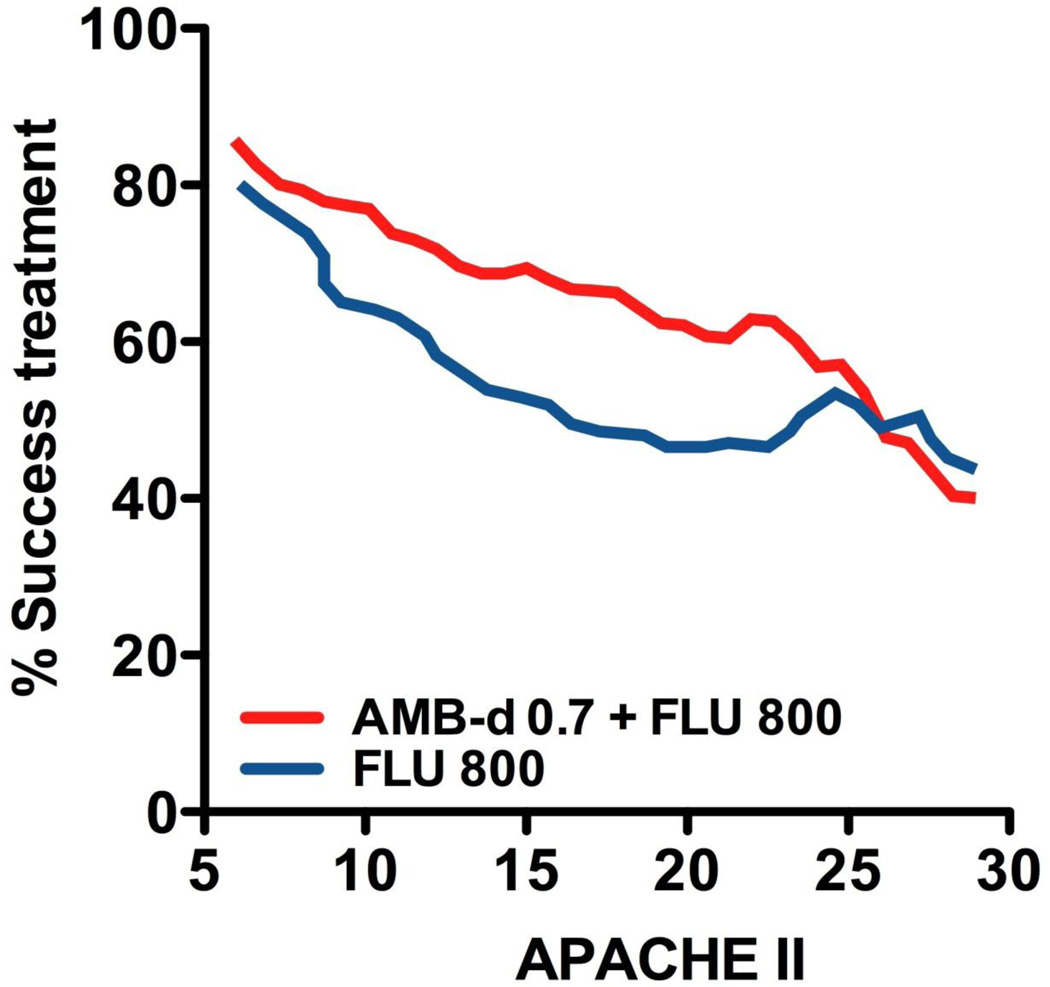

Delayed initiation of appropriate antifungal-based therapy is associated with high mortality rates in ICU patients with IC (Figs 1 and 2) [16]. However, early diagnosis and treatment of IC are not easy tasks, especially in patients with cancer, owing to a lack of specific signs and symptoms, confounding manifestations of the underlying malignant disease, decreased sensitivity and delayed time to positivity of blood cultures [10].

Fig. 1.

Effect of disease severity, expressed as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, on antifungal treatment success in patients with invasive candidiasis. Intervention with combination therapy is effective when applied early. AmB-d 0.7, amphotericin B deoxycholate 0.7 mg/kg/day; FLU 800, fluconazole 800 mg/day. Adapted from Rex et al. [68].

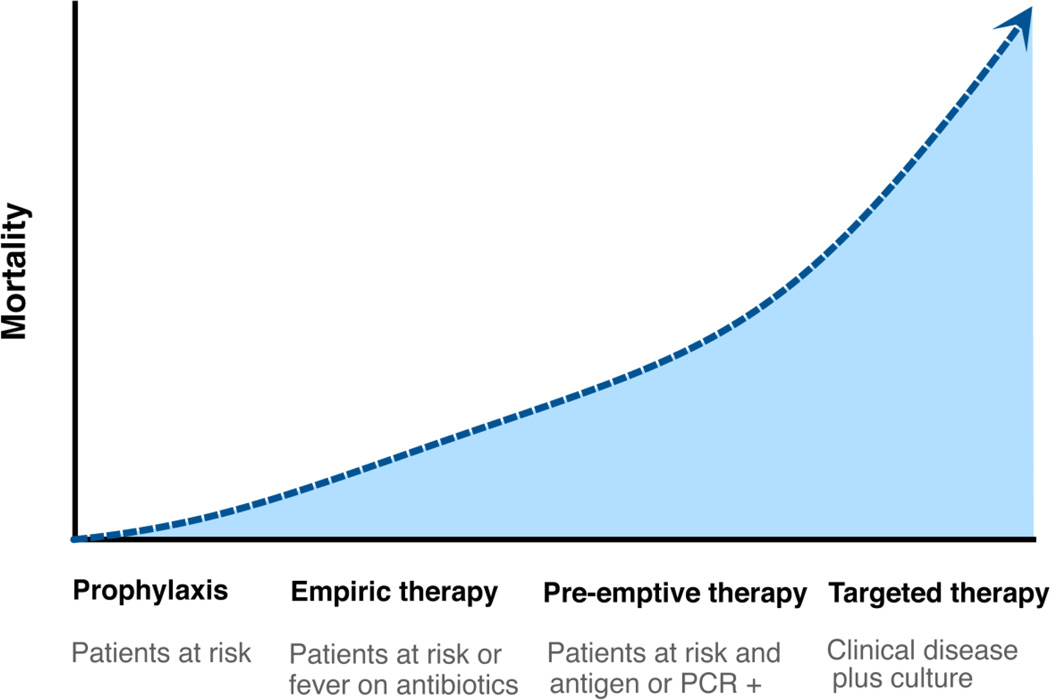

Fig. 2.

Timing of initiation of antifungals and mortality rates among cancer patients with invasive candidiasis. PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Researchers have used host risk factors and/or Candida spp. colonisation to create clinically relevant scores that can help clinicians identify ICU patients at highest risk for IC and those most likely to benefit from early treatment of IC [17]. In a pivotal study, Pittet et al. developed the colonisation index (CI), which is the number of distinct body sites colonised by Candida spp. divided by the total number of distinct sites tested per patient [8]. To increase the sensitivity and specificity of the CI, these authors proposed a corrected CI: the CI multiplied by the ratio of the number of body sites with heavy colonisation (assessed using semiquantitative cultures) to the total number of sites with growing Candida spp. The threshold for initiation of pre-emptive antifungal therapy was set at a CI of ≥0.5 or a corrected CI of ≥0.4 [8]. Other researchers developed a prediction rule for IC taking into account only clinical risk factors such as mechanical ventilation, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, placement of a CVC, use of TPN, use of dialysis, history of major surgery, pancreatitis, and use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents [17,18]. The same investigators applied this prediction rule to administration of risk-based prophylaxis with fluconazole to ICU patients, achieving a significant decrease in IC incidence, albeit with a small sample size [19]. A prospective, multicentre study of a cohort of Australian ICU patients validated this clinical predictive rule and showed a poor performance; however, the performance improved markedly with the post-hoc addition of colonisation parameters [20]. These data underline the complementary contribution of clinical risk factors and Candida colonisation to risk prediction models.

In fact, investigators in Spain adopted this combined approach, proposing the use of a ‘Candida score’ based on strong clinical predictors of IC along with multisite Candida colonisation [21]. Patients who had Candida scores >2.5 benefited from early treatment. The researchers validated this finding in a prospective study, which confirmed that IC development was highly improbable in patients with colonisation and Candida scores <3 [22].

Although these prediction rules were developed for ICU candidiasis, they do not apply to ICU patients with cancer because all of the relevant studies excluded neutropenic patients. Thus, no study has been designed to validate prediction rules in this high-risk population.

2.3. Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis in the intensive care unit

Timely diagnosis of IC remains a challenge in the ICU. Conventional blood culture systems lack sensitivity (<50%), especially in the setting of pre-existing antifungal therapy, and typically take several days to become positive. Furthermore, identification of a Candida yeast at the species level and delineation of its sensitivity to available antifungal agents may take an additional 48 h, although use of a new diagnostic technique using peptide nucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridisation shows the promise to decrease the time required to a few hours [23].

Because of delays in the diagnosis of frequently lethal IC, researchers have focused on developing non-culture-based diagnostic methods. Modern techniques allow for early detection of fungal nucleic acids, antibodies, and cell wall components such as mannan, galactomannan and the ‘pan-fungal’ marker β-(1,3)-d-glucan [24–26]. Detection of mannan and/or anti-mannan antibodies was effective in some studies, with sensitivity and specificity rates of 80–90% when these two tests were combined [24]. A meta-analysis of studies evaluating assays for detection of β-(1,3)-d-glucan in serum yielded a pooled sensitivity rate of 76.8% and specificity rate of 85.3% [27]. In the limited studies in ICUs, investigators found that the sensitivity and specificity of the method for identifying IC were 87% and 73%, respectively [28]. The most useful characteristic of these tests is their excellent negative predictive values, which can help rule out IC [26]. Molecular diagnostic tests used to detect Candida DNA in blood or tissue specimens are investigational, and how useful they are in ICU patients is unclear [29]. Several medically important Candida spp. produce large amounts of d-arabinitol in culture, and researchers have shown that serum d-arabinitol concentrations, serum d-arabinitol/creatinine ratios, and serum or urine d-arabinitol/l-arabinitol ratios are higher in patients with IC than in uninfected or colonised controls [30]. Although useful, this method is still investigational. Researchers found that serum procalcitonin may be helpful in early diagnosis of IC in Candida-colonised ICU non-cancer patients and improve the performance of the Candida score [31].

These non-culture-based diagnostics are expected to be introduced increasingly in the diagnosis of IC. Their exact role in the diagnostic algorithm remains unclear. Furthermore, their sensitivity for diagnosis of IC suffers from the lack of an appropriate ‘gold standard’, as the autopsy rates in ICU patients are very low. Tissue biopsies, such as punch biopsies of skin lesions and directed biopsies of involved organs, may be helpful in diagnosing IC.

Upper airway colonisation with Candida spp. and subsequent Candida-positive cultures of respiratory secretions are extremely common in ICU patients [32,33], whereas Candida pneumonia is rare, even in patients with cancer [32]. Therefore, cultures of respiratory secretions should not direct decisions regarding antifungal therapy [33].

Use of CVCs has become essential to the modern care of ICU patients but could serve as a nidus for candidaemia. The following criteria are used to diagnose catheter-related candidaemia: (i) no other apparent source of infection; (ii) the same Candida spp. is isolated both from peripheral blood and from catheter tip cultures [≥15 colony-forming units (CFU), analysed using a semiquantitative method]; and (iii) a quantitative blood culture collected via a CVC with at least five-fold more CFU/mm3 than in a concurrently obtained peripheral blood culture [34,35]. A sensitive but nonspecific marker for CVC-related candidaemia is the time needed to detect Candida spp. in peripheral blood cultures (time to positivity): a time to positivity >30 h can help exclude an intravascular catheter as the source of candidaemia [36].

2.4. Clinical aspects and mortality of invasive candidiasis in the intensive care unit

IC includes a wide spectrum of Candida infections such as candidaemia, skin and soft-tissue infections, endophthalmitis, endocarditis, meningitis, osteomyelitis and disseminated candidiasis. In ICU patients, the most common forms of IC are candidaemia (catheter-related or not) and intra-abdominal infections [37]. Candiduria is also extremely common in view of the widespread use of Foley catheters, but it rarely reflects invasive disease [38]. The clinical manifestations of IC in the ICU are similar to those of bacterial infections and range from protracted fever not responding to antimicrobials to a full-blown sepsis syndrome with multiorgan failure [39]. The clinical manifestations of IC in patients with cancer may also be influenced by the underlying malignancy and its treatment. For instance, physicians should consider hepatosplenic candidiasis in patients with acute leukaemia who continue to have persistent fever after neutrophil recovery [10].

Physicians typically observe a paucity of findings upon physical examination of ICU patients with IC. Clues indicating IC include skin lesions, soft-tissue abscesses and endophthalmitis. Skin lesions may be nodular, papular or can appear as painless pustules of various sizes on erythematous bases. In neutropenic cancer patients there is a wide spectrum of skin lesions, suggesting disseminated candidiasis [40]. Eye involvement is present in 2–26% of patients with documented candidaemia [41]. The main symptoms in these patients are decreased vision and ocular pain [41], which obviously are difficult to assess in sedated, intubated patients in the ICU. All ICU patients with candidaemia should undergo a thorough ophthalmological examination because early diagnosis of endophthalmitis is vital to preventing sight loss [41,42]. Interestingly, in patients with cancer having chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, endophthalmitis is uncommon [43].

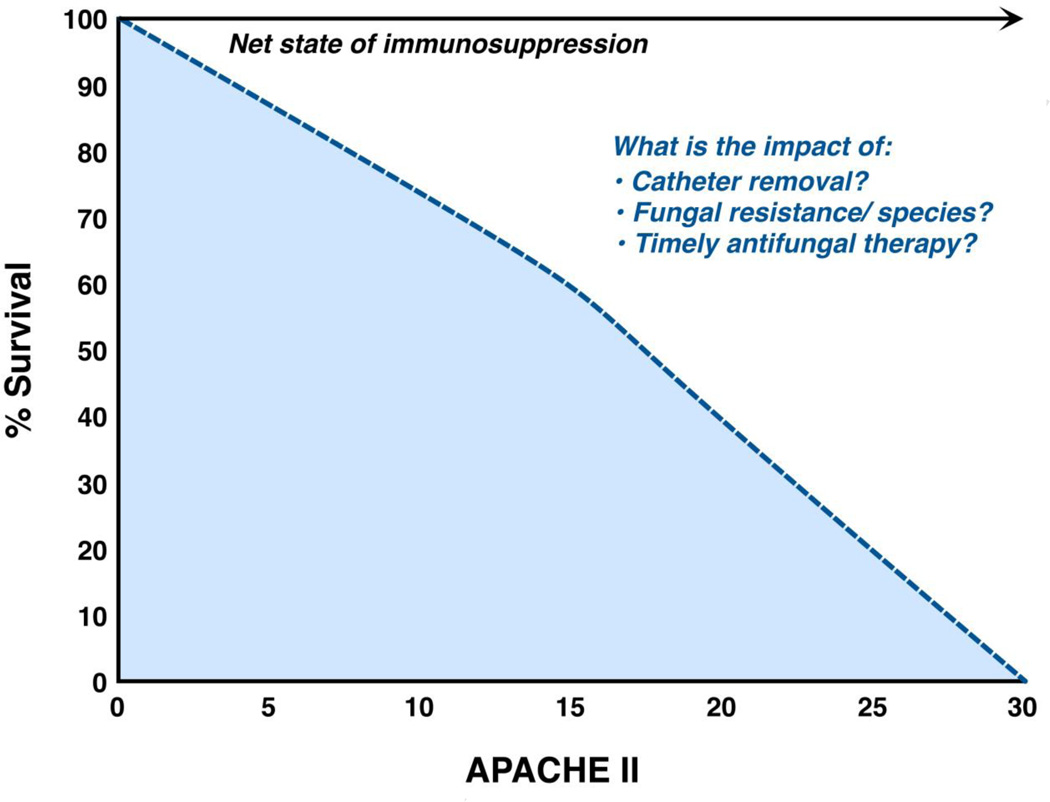

IC is recognised as a major cause of direct and indirect mortality (Fig. 3) both in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed critically ill patients [9,44], with crude and attributable mortality rates ranging from 40–78% and 20–40%, respectively [9,44]. An important point is that in immunosuppressed patients with cancer, IC is a ‘marker’ of severe, debilitating illness; differentiating the mortality directly attributable to IC from that caused by a concurrent infection or the underlying malignancy, especially without performing an autopsy, is difficult [45]. Infections with different Candida spp. have different mortality rates. For example, in the Prospective Antifungal Therapy Alliance database (2019 patients), infection with C. krusei had the highest mortality rate, whereas infection with C. parapsilosis had the lowest [4]. Also, a meta-analysis of seven randomised treatment trials in 1831 patients with IC identified infection with C. tropicalis as predictive of mortality [46]. In addition, the presence of fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates was associated with increased mortality in some [9,47] but not all studies. Of note is that in recent clinical trials of new antifungal agents, mortality rates were substantially lower, reflecting patient selection and exclusion of patients with cancer rather than better efficacy of the new agents [48–51]. Indeed, a recent, retrospective, single-institution study of unselected candidaemic patients with haematological malignancies showed that introduction of new antifungal agents into clinical practice did not particularly change the crude or attributable mortality rate [10].

Fig. 3.

Factors associated with increased mortality in intensive care unit cancer patients. APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score.

2.5. Treatment of invasive candidiasis in the intensive care unit (Fig. 2)

2.5.1. Prophylaxis

Small studies have suggested that azole-based prophylaxis can reduce the incidence of IC in non-neutropenic ICU patients, although its impact on overall mortality is unclear [52–54]. An important issue is determining how to identify high-risk patients likely to benefit from prophylaxis without unnecessarily indiscriminately giving prophylaxis to patients at low risk for IC. Indeed, according to a study in the Cochrane database, the number of patients who should receive fluconazole to prevent one case of IC was as high as 94 [53]. Such overuse of antifungals may lead to the emergence of drug-resistant Candida spp. [54]. In contrast, reduction of fluconazole use in the ICU led to a decreased incidence of IC caused by non-albicans Candida spp. [55]. The 2009 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines recommended prophylaxis with fluconazole at a dose of 400 mg (6 mg/kg) in high-risk adult patients in ICUs with a high incidence of IC [42]. It is important to know, however, that no specific data on prophylaxis exist for ICU patients with cancer. The broad-spectrum triazole posaconazole has been endorsed as prophylaxis in stable (non-ICU) patients with leukaemia or GvHD by various societies [56].

2.5.2. Early (empirical or pre-emptive) therapy for invasive candidiasis in intensive care unit patients with cancer

Results of retrospective studies have shown that reduced times to treatment of IC are correlated with reduced mortality rates [16]. Therefore, early ‘empirical’ treatment (i.e. before blood cultures are positive) in ICU patients at high risk for IC (e.g. patients who have febrile illness of no apparent cause who are not responding to treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics) is common [39]. Pre-emptive therapy is a strategy in which antifungal treatment is deferred until physicians obtain additional evidence of the presence of IC, such as infection-positive serological markers and imaging findings [57]. Researchers have shown that early pre-emptive therapy for IC based on multisite Candida colonisation and a positive β-(1,3)-d-glucan test reduced the incidence but not the mortality of candidaemia in ICU patients [57]. Regarding empirical therapy for IC, although an early study showed improved survival [58], a subsequent randomised, multicentre, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial showed that empirical treatment with fluconazole in ICU patients did not improve clinical outcomes [59]. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously since that study included many low-risk patients, not allowing an appropriate estimation of the protective effect of fluconazole.

2.5.3. Treatment of documented Candida infection

The choice of initial antifungal regimen for IC should be guided by the local epidemiology of Candida spp., prior azole exposure, history of intolerance to a particular antifungal agent, acuteness and severity of IC, co-morbidities, possible interactions with other drugs, and suspicion or evidence of involvement of the eye, central nervous system (CNS), cardiac valves and/or visceral organs [42]. Also, in vitro susceptibility data should be interpreted cautiously as they provide no ‘real-time’ information for the management of patients in the first crucial hours of IC. Notably, no studies have proven their usefulness in guidance of antifungal therapy, especially in patients with cancer [10,60]. In this era of an ever-expanding anti-Candida armamentarium, data on the efficacy of newer antifungals in patients with cancer having IC are insufficient, as randomised clinical trials of treatment of candidaemia primarily have included patients without underlying malignancy [60]. However, results of recent uncontrolled studies suggested that the new antifungals are effective in such patient populations [10,61].

The haemodynamic status of the patient and their prior exposure to antifungals are important criteria for selection of initial antifungal therapy. Thus, fluconazole is used for IC in haemodynamically stable patients with no history of azole exposure and no other risk factors for poor outcome. Typically, most patients with haematological malignancies do not fulfil this criterion. The typical fluconazole dosing schedule is a loading dose of 800 mg followed by 400 mg daily; ideally, the fluconazole dose should be based on mg/kg, especially in obese patients who might be underdosed [62]. Therapy with an echinocandin (e.g. caspofungin at a loading dose of 70 mg then 50 mg daily, micafungin at 100 mg daily, or anidulafungin at a loading dose of 200 mg then 100 mg daily) is preferred in haemodynamically unstable patients with recent azole exposure, immunosuppression, co-morbidities or at high risk for infections with non-albicans Candida spp., especially C. krusei and C. glabrata [42]. A recent, unpublished meta-analysis of seven randomised treatment trials in patients with IC suggested that echinocandin-based treatment is an independent predictor for improved survival and clinical success [46]. A high-dose caspofungin regimen (150 mg/day) and a standard-dose regimen (50 mg/day) in patients with proven IC (<10% with neutropenia) proved to be equally effective, safe and well tolerated [63]. Echinocandins should be used cautiously for IC caused by C. parapsilosis, although this is a matter of controversy [64]. In addition, echinocandin use should be avoided in patients with CNS or urinary tract infections or with endophthalmitis because of poor drug penetration in these sites. For patients who have initially received an echinocandin, transition to an oral azole such as fluconazole (i.e. treatment de-escalation) is recommended if they are clinically improved and the causative Candida isolates are likely to be azole-susceptible (e.g. C. albicans) [42].

Amphotericin B (AmB) [AmB deoxycholate (0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day) or liposomal AmB (L-AmB) (3–5 mg/kg/day)] are recommended as initial therapy in patients with a history of intolerance to echinocandins or azoles or when the infection is refractory and/or the pathogen is resistant to other antifungals [42]. Voriconazole (6 mg/kg given twice daily for two doses then 4 mg/kg given twice daily), although effective against IC, is a less attractive first-line agent because of disadvantages such as twice-daily dosing and variability in blood levels.

The need for and timing of CVC removal in candidaemic patients, especially those with cancer and/or neutropenia, are controversial. Most published studies suggested that early removal of CVC (i.e. <48 h after the onset of candidaemia) is associated with reduced mortality rates [35]. However, a recent subgroup analysis of two clinical trials including 842 patients with candidaemia found that early CVC removal was not clinically beneficial [65]. In contrast, a meta-analysis of seven randomised trials of treatment of IC showed that CVC removal improved survival and clinical outcomes independent of the infecting Candida spp. or disease severity [46]. Well-designed, prospective, randomised trials with CVC management as the primary end-point are required to address CVC removal. In the everyday practice of an ICU, patients usually have multiple intravascular lines and in case of documented candidaemia there is an uncertainty on the ideal management (e.g. time and sequence of line removal). The best practice is to remove the non-tunnelled and try to rescue the tunnelled lines. Exchange of lines over a J-wire is not an acceptable option as it propagates the new line infection. Use of antifungal locks may be considered as catheter salvage therapy when catheter removal is not logistically feasible [66].

The duration of IC treatment is ≥2 weeks after clearance of a Candida spp. from the bloodstream and resolution of all symptoms and signs of systematic or focal infection [42]. Failure to control IC despite appropriate antifungal-based treatment usually results from a persistent focus of infection with resistant Candida spp. or prolonged immune suppression and is associated with high mortality rates. Therapeutic options in such cases are limited and of questionable efficacy; they include salvage therapy with new antifungals [67], increased dosing of an appropriate antifungal [68], combination therapy [69] and/or adjunct immunotherapy [70].

Candiduria in ICU patients is a marker of heavy Candida colonisation, with incidences ranging from 19% to 44% [38]. The main predisposing factor is bladder catheterisation, and catheter removal is commonly sufficient to eliminate candiduria [42]. In immunocompromised ICU patients, candiduria may not be so benign and is occasionally associated with disseminated infections and increased mortality rates [71]. Therefore, systemic antifungal-based treatment should be considered for ICU patients with cancer having unexplained fever and candiduria in whom IC is suspected. In a placebo-controlled study, oral fluconazole and catheter removal were effective in short-term eradication of candiduria [71]. Bladder irrigation with AmB is logistically difficult and of limited therapeutic value [72].

3. Aspergillosis in the intensive care unit

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) primarily affects immunocompromised individuals but is now recognised as an emerging infection, typically pneumonia, in ICU patients [73]. The incidence of IA in ICUs ranges from 0.33% to 19.0% [74] and it is associated with underlying structural lung disease, systemic corticosteroids, extended ICU stays and prolonged ventilator dependence [74]. The reasons for the incidence variation among ICUs are a lack of autopsy studies, difficulty in discriminating between colonisation and invasive infection, and the low sensitivity and specificity of available serological diagnostic tools. In fact, underdiagnosis of IA in ICU patients is a common finding of autopsy studies [75]. In particular, ICU patients with cancer are at increased risk for IA because they typically have multiple risk factors, including: prolonged, severe neutropenia; uncontrolled haematological malignancies; allogeneic HSCT; and receipt of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive treatment [74].

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary IA include fever not responding to antibiotics, cough, dyspnoea and pleuritic chest pain. However, these signs may be non-specific in sedated, ventilated ICU patients with cancer. Timely diagnosis of IA in the ICU remains elusive. The gold standard is histological diagnosis, but obtaining tissue samples from frail, critically ill, frequently thrombocytopenic patients with cancer may not be feasible. Non-culture-based diagnostic methods such as galactomannan antigen detection, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification and β-(1,3)-d-glucan assays do not have sufficient sensitivity or specificity for routine clinical use, especially in the ICU [76,77]. Use of both β-(1,3)-d-glucan and galactomannan detection in the ICU is hampered by many false-positive results for various reasons [76,77]. However, galactomannan detection in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is promising for detection of pulmonary aspergillosis in the ICU [78]. Typical imaging findings, such as the halo sign, play an important role in early diagnosis of IA in neutropenic patients [79] but are frequently absent in ICU patients [80]. Isolation of Aspergillus spp. from the lower respiratory tract in critically ill, heavily immunocompromised patients is highly associated with pulmonary IA [81].

IA in ICU has high crude (≥80%) and attributable (18–48%) mortality rates despite the introduction of new antifungals [73,74]. However, no study has evaluated the optimal management of IA in the ICU setting. Voriconazole and L-AmB are reasonable therapeutic agents for pulmonary IA [82]. Salvage therapy options for refractory disease include caspofungin, posaconazole, micafungin, high-dose L-AmB, and combination therapy with an echinocandin plus voriconazole or L-AmB [82]. However, prospective clinical trials are needed to assess the efficacy of combination therapy [83].

Other treatment issues pertaining to IA in ICU patients with cancer include the pharmacokinetic profiles and optimal dosing of antifungals in patients with renal and/or hepatic dysfunction, drug interactions including drugs commonly used in the ICU such as paralysing/sedating agents, proton pump inhibitors and broad-spectrum antibacterials, the best route of administration and the value of drug-level monitoring.

4. Mucormycosis and other unusual fungal infections in the intensive care unit

Mucormycosis has emerged as an increasingly important pathogen, mainly in recipients of HSCT and patients with haematological malignancies, many of whom are admitted to the ICU [84]. The most common sites of mucormycosis are the sinuses, lung, brain, gastrointestinal tract and skin. Invasive mucormycosis outbreaks have occurred in ICU patients in association with the use of contaminated bandages or tongue depressors [85]. The diagnosis of mucormycosis is mainly histological, whereas certain imaging findings (e.g. the reverse halo sign) suggest pulmonary mucormycosis [79,86]. Mucormycosis is frequently a devastating infection, with mortality rates of up to 85% [87] depending on factors such as the severity of the underlying disease, prompt initiation of treatment with effective antifungals, correction of metabolic risk factors, and early, aggressive surgical intervention. The antifungal agent of choice for mucormycosis is L-AmB given alone or with an echinocandin [88]. Posaconazole and the iron chelator deferasirox can be used as salvage therapy [88]. Selected patients have received adjunct therapy with recombinant cytokines, hyperbaric oxygen and/or granulocyte transfusions, with moderate success [88].

Fusarium spp. infections mainly affect heavily immunocompromised patients with haematological malignancies or HSCT recipients, many of whom are admitted to the ICU [89]. Fusariosis is a dreadful infection, with mortality rates approaching 100% if patients do not undergo immune recovery [90]. The primary antifungal agents for fusariosis are voriconazole [91] and L-AmB. Salvage treatment options include posaconazole [92] and white cell transfusions.

Trichosporon spp. are non-Candida yeasts that can cause invasive infections, especially in neutropenic patients with haematological malignancies, with reported mortality rates as high as 77% [93,94]. As with all opportunistic mycoses, an ICU stay is a poor prognostic factor for patients with cancer having trichosporonosis [93]. Trichosporonosis can be classified in three categories: disseminated disease; focal visceral disease; and catheter-related disease without tissue invasion [94]. The clinical picture of trichosporonosis is indistinguishable from that of IC [93]. The primary antifungal agent for trichosporonosis is voriconazole, although its use is based on limited data [94]. Trichosporon spp. are typically resistant to AmB and echinocandins [93,94]. Therefore, physicians should be aware that in patients with haematological malignancies, a ‘yeast’ in a blood culture may not be a Candida spp. but rather an endemic or rare fungal species inherently resistant to echinocandins.

Scedosporium spp. infection is a rare opportunistic mycosis caused by the multidrug-resistant dematiaceous fungi Scedosporium apiospermum and Scedosporium prolificans. In a recent study of patients with cancer having scedosporiosis, ICU admission was associated with a mortality rate of 64% [95].

5. Infection control

Surveillance for IFIs in ICUs is essential to determine the incidence of IFIs, to delineate the epidemiology of and susceptibility to infection with pathogenic fungal species, to detect outbreaks and clonal fungal populations and to support effective infection control programmes. Enhanced understanding of the epidemiology of IFIs in the ICU will allow for implementation of prediction rules specifically for cancer patients as well as judicious use of antifungal-based prophylaxis. Prevention protocols designed to reduce ICU patients’ exposure to risk factors, with an emphasis on compliance with hygiene recommendations, avoidance of the use of invasive devices (particularly CVCs and urinary catheters) whenever feasible and discontinuation of use of these devices as soon as possible, are of paramount importance.

6. Conclusions and future directions

Despite the introduction of new antifungal agents with improved activity and reduced toxicity, mortality rates remain high in ICU patients with cancer. The goals in the near future include: close monitoring of the ever-changing epidemiology of IFIs in ICUs in cancer hospitals; refinement of existing risk stratification models and development of novel, highly sensitive, specific diagnostic tools for early detection of infection, thus allowing a pre-emptive and not empirical therapeutic approach; development of more effective, less toxic antifungals; development of new therapeutic and prophylactic protocols; use of prognostic biomarkers for treatment efficacy monitoring; and implementation of antifungal stewardship programs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key future directions for research in intensive care unit (ICU) cancer patients with invasive fungal infections (IFIs)

|

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Russell E. Lewis for assistance with the figures.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support grant CA016672.

DPK has received research support and honoraria from Schering-Plough, Pfizer, Astella Pharma Inc., Enzon Pharmaceuticals and Merck and Co., Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests

NVS declares no competing conflicts

Ethical approval

Not required.

References

- 1.Chow JK, Golan Y, Ruthazer R, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y, Lichtenberg DA, et al. Risk factors for albicans and non-albicans candidemia in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1993–1998. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816fc4cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, Horan TC, Sievert DM, Pollock DA, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network Team; Participating National Healthcare Safety Network Facilities. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:996–1011. doi: 10.1086/591861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leroy O, Gangneux JP, Montravers P, Mira JP, Gouin F, Sollet JP, et al. AmarCand Study Group. Epidemiology, management, and risk factors for death of invasive Candida infections in critical care: a multicenter, prospective, observational study in France (2005–2006) Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1612–1618. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819efac0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horn DL, Neofytos D, Anaissie EJ, Fishman JA, Steinbach WJ, Olyaei AJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 2019 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy Alliance registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1695–1703. doi: 10.1086/599039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kett DH, Azoulay E, Echeverria PM, Vincent JL. Extended Prevalence of Infection in ICU Study (EPIC II) Group of Investigators. Candida bloodstream infections in intensive care units: analysis of the Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care Unit Study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:665–670. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206c1ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassetti M, Righi E, Costa A, Fasce R, Molinari MP, Rosso R, et al. Epidemiological trends in nosocomial candidemia in intensive care. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg HM, Jarvis WR, Soucie JM, Edwards JE, Patterson JE, Pfaller MA, et al. National Epidemiology of Mycoses Survey (NEMIS) Study Group. Risk factors for candidal bloodstream infections in surgical intensive care unit patients: the NEMIS prospective multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:177–186. doi: 10.1086/321811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittet D, Monod M, Suter PM, Frenk E, Auckenthaler R. Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 1994;220:751–758. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slavin MA, Sorrell TC, Marriott D, Thursky KA, Nguyen Q, Ellis DH, et al. Australian Candidemia Study, Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases. Candidaemia in adult cancer patients: risks for fluconazole-resistant isolates and death. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1042–1051. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sipsas NV, Lewis RE, Tarrand J, Hachem R, Rolston KV, Raad II, et al. Candidemia in patients with hematologic malignancies in the era of new antifungal agents (2001–2007): stable incidence but changing epidemiology of a still frequently lethal infection. Cancer. 2009;115:4745–4752. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leroy O, Mira JP, Montravers P, Gangneux JP, Lortholary O. AmarCand Study Group. Comparison of albicans vs. non-albicans candidemia in French intensive care units. Crit Care. 2010;14:R98. doi: 10.1186/cc9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow JK, Golan Y, Ruthazer R, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y, Lichtenberg D, et al. Factors associated with candidemia caused by non-albicans Candida species versus Candida albicans in the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1206–1213. doi: 10.1086/529435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Playford EG, Marriott D, Nguyen Q, Chen S, Ellis D, Slavin M, et al. Candidemia in nonneutropenic critically ill patients: risk factors for non-albicans Candida spp. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2034–2039. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181760f42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holley A, Dulhunty J, Blot S, Lipman J, Lobo S, Dancer C, et al. Temporal trends, risk factors and outcomes in albicans and non-albicans candidaemia: an international epidemiological study in four multidisciplinary intensive care units. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:554. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.035. e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lortholary O, Desnos-Ollivier M, Sitbon K, Fontanet A, Bretagne S, Dromer F. French Mycosis Study Group. Recent exposure to caspofungin or fluconazole influences the epidemiology of candidemia: a prospective multicenter study involving 2,441 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:532–538. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01128-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garey KW, Rege M, Pai MP, Mingo DE, Suda KJ, Turpin RS, et al. Time to initiation of fluconazole therapy impacts mortality in patients with candidemia: a multi-institutional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:25–31. doi: 10.1086/504810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Sable C, Sobel J, Alexander BD, Donowitz G, Kan V, et al. Multicenter retrospective development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for nosocomial invasive candidiasis in the intensive care setting. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pappas PG, Shoham S, Reboli A, Barron MA, Sims C, et al. Improvement of a clinical prediction rule for clinical trials on prophylaxis for invasive candidiasis in the intensive care unit. 2011;54:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faiz S, Neale B, Rios E, Campos T, Parsley E, Patel B, et al. Risk-based fluconazole prophylaxis of Candida bloodstream infection in a medical intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:689–692. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0666-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Playford EG, Lipman J, Kabir M, McBryde ES, Nimmo GR, Lau A, et al. Assessment of clinical risk predictive rules for invasive candidiasis in a prospective multicentre cohort of ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2141–2145. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1619-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.León C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Almirante B, Nolla-Salas J, Alvarez-Lerma F, et al. EPCAN Study Group. A bedside scoring system (“Candida score”) for early antifungal treatment in nonneutropenic critically ill patients with Candida colonization. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:730–737. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000202208.37364.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Galván B, Blanco A, Castro C, et al. Cava Study Group. Usefulness of the “Candida score” for discriminating between Candida colonization and invasive candidiasis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1624–1633. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819daa14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gherna M, Merz WG. Identification of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata within 1.5 hours directly from positive blood culture bottles with a shortened peptide nucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridization protocol. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:247–248. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01241-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sendid B, Poirot JL, Tabouret M, Bonnin A, Caillot D, Camus D, et al. Combined detection of mannanaemia and antimannan antibodies as a strategy for the diagnosis of systemic infection caused by pathogenic Candida species. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:433–442. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-5-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Persat F, Topenot R, Piens MA, Thiebaut A, Dannaoui E, Picot S. Evaluation of different commercial ELISA methods for the serodiagnosis of systemic candidosis. Mycoses. 2002;45:455–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2002.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Alexander BD, Kett DH, Vazquez J, Pappas PG, Saeki F, et al. Multicenter clinical evaluation of the (1→3) β-d-glucan assay as an aid to diagnosis of fungal infections in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:654–659. doi: 10.1086/432470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karageorgopoulos DE, Vouloumanou EK, Ntziora F, Michalopoulos A, Rafailidis PI, Falagas ME. β-d-glucan assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:750–770. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohr JF, Sims C, Paetznick V, Rodriguez J, Finkelman MA, Rex JH, et al. Prospective survey of (1→3)-β-d-glucan and its relationship to invasive candidiasis in the surgical intensive care unit setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:58–61. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01240-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morace G, Pagano L, Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Mele L, Equitani F, et al. PCR-restriction enzyme analysis for detection of Candida DNA in blood from febrile patients with hematological malignancies. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1871–1875. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1871-1875.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehtonen L, Anttila VJ, Ruutu T, Salonen J, Nikoskelainen J, Eerola E, et al. Diagnosis of disseminated candidiasis by measurement of urine d-arabinitol/l-arabinitol ratio. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2175–2179. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2175-2179.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles PE, Castro C, Ruiz-Santana S, León C, Saavedra P, Martín E. Serum procalcitonin levels in critically ill patients colonized with Candida spp: new clues for the early recognition of invasive candidiasis? Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2146–2150. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1623-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kontoyiannis DP, Reddy BT, Torres HA, Luna M, Lewis RE, Tarrand J, et al. Pulmonary candidiasis in patients with cancer: an autopsy study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:400–403. doi: 10.1086/338404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood GC, Mueller EW, Croce MA, Boucher BA, Fabian TC. Candida sp. isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage: clinical significance in critically ill trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:599–603. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-0065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antoniadou A, Torres HA, Lewis RE, Thornby J, Bodey GP, Tarrand JP, et al. Candidemia in a tertiary care cancer center: in vitro susceptibility and its association with outcome of initial antifungal therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:309–321. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000091182.93122.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raad I, Hanna H, Boktour M, Girgawy E, Danawi H, Mardani M, et al. Management of central venous catheters in patients with cancer and candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1119–1127. doi: 10.1086/382874. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ben-Ami R, Weinberger M, Orni-Wasserlauff R, Schwartz D, Itzhaki A, Lazarovitch T, et al. Time to blood culture positivity as a marker for catheter-related candidemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2222–2226. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00214-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D. Management of Candida species infections in critically ill patients. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:772–785. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00831-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toya SP, Schraufnagel DE, Tzelepis GE. Candiduria in intensive care units: association with heavy colonization and candidaemia. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golan Y, Wolf MP, Pauker SG, Wong JB, Hadley S. Empirical anti-Candida therapy among selected patients in the intensive care unit: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:857–869. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodey GP. Dermatologic manifestations of infections in neutropenic patients. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:655–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oude Lashof AM, Rothova A, Sobel JD, Ruhnke M, Pappas PG, Viscoli C, et al. Ocular manifestations of candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:262–268. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swerdloff JN, Filler SG, Edwards JE., Jr Severe candidal infections in neutropenic patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl 2):S457–S467. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimopoulos G, Karabinis A, Samonis G, Falagas ME. Candidemia in immunocompromised and immunocompetent critically ill patients: a prospective comparative study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:377–384. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0316-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaoutis TE, Argon J, Chu J, Berlin JA, Walsh TJ, Feudtner C. The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1232–1239. doi: 10.1086/496922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andes DR, Safdar N, Baddley J, et al. 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) Boston, MA. Washington, DC: ASM Press; Sep 12–15, 2010. Impact of therapy on mortality across Candida spp in patients with invasive candidiasis from randomized clinical trials: a patient level analysis. 2010. Abstract M-1312. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baddley JW, Patel M, Bhavnani SM, Moser SA, Andes DR. Association of fluconazole pharmacodynamics with mortality in patients with candidemia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3022–3028. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00116-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mora-Duarte J, Betts R, Rotstein C, Colombo AL, Thompson-Moya L, Smietana J, et al. Caspofungin Invasive Candidiasis Study Group. Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2020–2029. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kullberg BJ, Sobel JD, Ruhnke M, Pappas PG, Viscoli C, Rex JH, et al. Voriconazole versus a regimen of amphotericin B followed by fluconazole for candidaemia in non-neutropenic patients: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1435–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuse ER, Chetchotisakd P, da Cunha CA, Ruhnke M, Barrios C, Raghunadharao D, et al. Micafungin Invasive Candidiasis Working Group. Micafungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for candidaemia and invasive candidosis: a phase III randomized double-blind trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reboli AC, Rotstein C, Pappas PG, Chapman SW, Kett DH, Kumar D, et al. Anidulafungin Study Group. Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2472–2482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eggimann P, Francioli P, Bille J, Schneider R, Wu MM, Chapuis G, Chiolero R, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis prevents intra-abdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1066–1072. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199906000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Playford EG, Webster AC, Sorrell TC, Craig JC. Antifungal agents for preventing fungal infections in non-neutropenic critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004920. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004920.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rocco TR, Reinert SE, Simms HH. Effects of fluconazole administration in critically ill patients: analysis of bacterial and fungal resistance. Arch Surg. 2000;135:160–165. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bassetti M, Ansaldi F, Nicolini L, Malfatto E, Molinari MP, Mussap M, et al. Incidence of candidaemia and relationship with fluconazole use in an intensive care unit. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:625–629. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Comely OA, Böhme A, Buchheidt D, Einsele H, Heinz WJ, Karthaus M, et al. Primary prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies. Recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society for Haematology and Oncology. Haematologica. 2009;94:113–122. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piarroux R, Grenouillet F, Balvay P, Tran V, Blasco G, Millon L, et al. Assessment of preemptive treatment to prevent severe candidiasis in critically ill surgical patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2443–2449. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000147726.62304.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parkins MD, Sabuda DM, Elsayed S, Laupland KB. Adequacy of empirical antifungal therapy and effect on outcome among patients with invasive Candida species infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:613–618. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schuster MG, Edwards JE, Jr, Sobel JD, Darouiche RO, Karchmer AW, Hadley S, et al. Empirical fluconazole versus placebo for intensive care unit patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:83–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kontoyiannis DP. Echinocandin-based initial therapy in fungemic patients with cancer: a focus on recent guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:638–639. doi: 10.1086/603585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sipsas NV, Lewis RE, Raad II, Kontoyiannis DP. Monotherapy with caspofungin for candidaemia in adult patients with cancer: a retrospective, single institution study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pittrow L, Penk A. Special pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in septic, obese and burn patients. Mycoses. 1999;42(Suppl 2):87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Betts RF, Nucci M, Talwar D, Gareca M, Queiroz-Telles F, Bedimo RJ, et al. Caspofungin High-Dose Study Group. A multicenter, double-blind trial of a high-dose caspofungin treatment regimen versus a standard caspofungin treatment regimen for adult patients with invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1676–1684. doi: 10.1086/598933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colombo AL, Ngai AL, Bourque M, Bradshaw SK, Strohmaier KM, Taylor AF, et al. Caspofungin use in patients with invasive candidiasis caused by common non-albicans Candida species: review of the caspofungin database. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1864–1871. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00911-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nucci M, Anaissie E, Betts RF, Dupont BF, Wu C, Buell DN, et al. Early removal of central venous catheter in patients with candidemia does not improve outcome: analysis of 842 patients from 2 randomized clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:295–303. doi: 10.1086/653935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raad II, Hachem RY, Hanna HA, Fang X, Jiang Y, Dvorak T, et al. Role of ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) in catheter lock solutions: EDTA enhances the antifungal activity of amphotericin B lipid complex against Candida embedded in biofilm. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:515–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Oude Lashof AM, Kullberg BJ, Rex JH. Voriconazole salvage treatment of invasive candidiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:651–655. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rex JH, Pappas PG, Karchmer AW, Sobel J, Edwards JE, Hadley S, et al. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group. A randomized and blinded multicenter trial of high-dose fluconazole plus placebo versus fluconazole plus amphotericin B as therapy for candidemia and its consequences in nonneutropenic subjects. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1221–1228. doi: 10.1086/374850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sobel JD. Combination therapy for invasive mycoses: evaluation of past clinical trial designs. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(Suppl 4):S224–S227. doi: 10.1086/421961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kullberg BJ, Oude Lashof AM, Netea MG. Design of efficacy trials of cytokines in combination with antifungal drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(Suppl 4):S218–S223. doi: 10.1086/421960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sobel JD, Kauffman CA, McKinsey D, Zervos M, Vazquez JA, Karchmer AW, et al. Candiduria: a randomized, double-blind study of treatment with fluconazole and placebo. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Mycoses Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:19–24. doi: 10.1086/313580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drew RH, Arthur RR, Perfect JR. Is it time to abandon the use of amphotericin B bladder irrigation? Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1465–1470. doi: 10.1086/429722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vandewoude KH, Blot SI, Benoit D, Colardyn F, Vogelaers D. Invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: attributable mortality and excesses in length of ICU stay and ventilator dependence. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Van Wijngaerden E. Invasive aspergillosis in the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:205–216. doi: 10.1086/518852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roosen J, Frans E, Wilmer A, Knockaert D, Bobbaers H. Comparison of premortem clinical diagnoses in critically ill patients and subsequent autopsy findings. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:562–567. doi: 10.4065/75.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Digby J, Kalbfleisch J, Glenn A, Larsen A, Browder W, Williams D. Serum glucan levels are not specific for presence of fungal infections in intensive care unit patients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:882–885. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.5.882-885.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.De Vlieger G, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Verbeken E, Meersseman W, Van Wijngaerden E. β-d-glucan detection as a diagnostic test for invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised critically ill patients with symptoms of respiratory infection: an autopsy-based study. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3783–3787. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00879-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Vanderschueren S, et al. Galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: a tool for diagnosing aspergillosis in intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:27–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-606OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Georgiadou SP, Sipsas NV, Marom EM, Kontoyiannis DP. The diagnostic value of halo and reversed halo signs for invasive mold infections in compromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1144–1155. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vandewoude KH, Vogelaers D. Medical imaging and timely diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:380–381. doi: 10.1086/509931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khasawneh F, Mohamad T, Moughrabieh MK, Lai Z, Ager J, Soubani AO. Isolation of Aspergillus in critically ill patients: a potential marker of poor outcome. J Crit Care. 2006;21:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:327–360. doi: 10.1086/525258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marr KA, Boeckh M, Carter RA, Kim HW, Corey L. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:797–802. doi: 10.1086/423380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kontoyiannis DP, Lionakis MS, Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Healy M, Perego C, et al. Zygomycosis in a tertiary-care cancer center in the era of Aspergillus-active antifungal therapy: a case–control observational study of 27 recent cases. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1350–1360. doi: 10.1086/428780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maraví-Poma E, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, de Jalón JG, Manrique-Larralde A, Torroba L, Urtasun J, et al. Outbreak of gastric mucormycosis associated with the use of wooden tongue depressors in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:724–728. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wahba H, Truong MT, Lei X, Kontoyiannis DP, Marom EM. Reversed halo sign in invasive pulmonary fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1733–1737. doi: 10.1086/587991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP, Edwards J, Jr, Ibrahim AS. Recent advances in the management of mucormycosis: from bench to bedside. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1743–1751. doi: 10.1086/599105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Campo M, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Invasive fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancies at a cancer center: 1998–2009. J Infect. 2010;60:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Boutati EI, Anaissie EJ. Fusarium, a significant emerging pathogen in patients with hematologic malignancy: ten years’ experience at a cancer center and implications for management. Blood. 1997;90:999–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perfect JR, Marr KA, Walsh TJ, Greenberg RN, DuPont B, de la Torre-Cisneros J, et al. Voriconazole treatment for less-common, emerging, or refractory fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1122–1131. doi: 10.1086/374557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raad II, Hachem RY, Herbrecht R, Graybill JR, Hare R, Corcoran G, et al. Posaconazole as salvage treatment for invasive fusariosis in patients with underlying hematologic malignancy and other conditions. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1398–1403. doi: 10.1086/503425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kontoyiannis DP, Torres HA, Chagua M, Hachem R, Tarrand JJ, Bodey GP, et al. Trichosporonosis in a tertiary care cancer center: risk factors, changing spectrum and determinants of outcome. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:564–569. doi: 10.1080/00365540410017563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Girmenia C, Pagano L, Martino B, D’Antonio D, Fanci R, Specchia G, et al. GIMEMA Infection Program. Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon species and Geotrichum capitatum in patients with hematological malignancies: a retrospective multicenter study from Italy and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1818–1828. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1818-1828.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lamaris GA, Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Safdar A, Raad II, Kontoyiannis DP. Scedosporium infection in a tertiary care cancer center: a review of 25 cases from 1989–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1580–1584. doi: 10.1086/509579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]