Abstract

Background

Opioid prescribing for non-cancer pain has increased dramatically. We examined whether the prevalence of unhealthy lifestyles, psychological distress, healthcare utilization, and co-prescribing of sedative-hypnotics increased with increasing duration of prescription opioid use.

Methods

We analyzed electronic data for 6 months before and after an index visit for back pain in a large managed care plan. Use of opioids was characterized as “none”, “acute” (≤ 90 days), “episodic”, or “long-term.” Associations with lifestyle factors, psychological distress, and utilization were adjusted for demographics and comorbidity.

Results

There were 26,014 eligible patients. Among these, 61% received a course of opioid therapy, and 19% were long-term users. Psychological distress, unhealthy lifestyles, and utilization were associated in stepwise fashion with duration of opioid prescribing, not just with chronic use. Among long-term opioid users, 59% received only short-acting drugs; 39% received both long and short acting drugs; 44% received a sedative-hypnotic. Of those with any opioid use, 36% had an emergency visit.

Conclusions

Opioid prescribing was common among patients with back pain. The prevalence of psychological distress, unhealthy lifestyles, and healthcare utilization increased incrementally with duration of opioid use. Despite safety concerns, co-prescribing of sedative-hypnotics was common. These data may help in predicting long-term opioid use and improving the safety of opioid prescribing.

Chronic pain is a common complaint in primary care. Over 2% of U.S. adults report regular use of prescription opioids, and more than half of these have chronic back pain.1 Surveys suggest that many such patients have persistent high levels of pain and poor quality of life.2 Despite uncertainties about long-term efficacy and safety for chronic back pain, prescription opioid use has increased rapidly, and complications related to overdoses and diversion have risen in parallel.3–11

Patients with anxiety or depression are more likely than others to have opioids prescribed, yet have less analgesic benefit, are more prone to medication misuse, and are more likely to use psychoactive drugs.12–14 Whether psychological distress is associated with acute opioid use, as opposed to chronic use, is unclear. A few studies have suggested that lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity are predictors of opioid misuse or early opioid prescriptions for pain, but these associations have not been well-studied in routine clinical care [Tetrault, Stover & Franklin]. Certain opioid prescribing patterns raise important safety concerns. For example, co-prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines is recognized as a risk for unintentional overdose and death [Dunn, Franklin], but the frequency of such prescribing in routine care is not well characterized.

Given these uncertainties, it is important to better understand which patients are most likely to receive opioids and whether certain patient characteristics are associated with long-term use. There is also a need for better data on related health services consumption and patient safety concerns (such as co-prescription of sedative-hypnotics),.

We used electronic health records for primary care patients with chronic back pain in a large managed care plan to examine patterns of opioid use.. Our goals were to clarify the nature of associations between mental health, lifestyle, and opioid prescribing, and to identify potential strategies for improving the efficiency and safety of opioid prescribing in primary care. Our study aims were:

To examine patient and prescribing characteristics associated with long-term opioid use. We hypothesized that diagnoses of substance abuse, depression, and anxiety would be associated with higher rates of long-term opioid use. We also hypothesized that lifestyle factors (obesity, smoking) and greater comorbidity would be associated with greater opioid use. We further sought to determine whether these characteristics were associated only with long term opioid use or also with acute use, perhaps in a stepwise incremental fashion.

To examine the prevalence of a patient safety concern: co-prescription of sedative-hypnotics and opioids. We hypothesized that co-prescription of sedative-hypnotics may be common, despite cautions against this practice.

To describe use of other health care services that may be associated with opioid use, including emergency room use and other clinic visits. We hypothesized that among all patients with back pain, emergency room use and clinic visit frequency would be higher among opioid users than non-users.

Such analyses would help to clarify the likelihood of long-opioid use among certain patients; determine if risky co-prescribing is an important problem; and suggest strategies for providing more efficient care for an often challenging patient group.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted the study in the Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) health care system in Portland, Oregon. KPNW is a federally qualified, not-for-profit HMO serving more than 470,000 members in northwest Oregon and southwest Washington. Members are demographically representative of the coverage area and represent about 17% of the area’s population.

KPNW maintains one hospital and 26 outpatient medical offices. An integrated, group-model delivery system provides the entire scope of care for members. Each health plan member receives a unique health record number upon enrollment, which continues even through gaps in membership. Contacts with the medical care system and referrals to outside services are recorded in an electronic medical record. This computerized process stores patient demographics, medical history, and visit summaries. KPNW’s data systems are accessible for research purposes; all members are informed of this as part of their membership agreement, and can elect to be excluded from all or some research studies. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research and at Oregon Health and Science University.

KPNW provides prescriptions at a reduced cost, and prescriptions are prepaid for a significant proportion of the population. The automated outpatient pharmacy system records all prescriptions dispensed. Based on a membership survey, an estimated 90 percent of prescriptions are filled at a program pharmacy, including those for members without a prepaid drug benefit. For our study, we required that patients have one year of continuous membership and drug coverage prior to the index visit. Because of that coverage requirement, study patients had financial and logistical incentives to use KPNW pharmacies for their prescriptions. While KPNW has a formulary of recommended medications, physicians may prescribe any marketed drug.

Health plan members are encouraged to choose a personal physician and return to that physician for medical care. Family practitioners, internists, and pediatricians provide primary care and maintain continuity of treatment.

Patients

We studied adult ambulatory patients aged 18 and over. To select patients with back pain, we chose as an index visit the first visit in 2004 with any one of 32 ICD-9-CM diagnoses associated with low back pain,15 and used electronic pharmacy and medical record data for 1 year before and 6 months after an index visit. To focus on patients with musculoskeletal back pain, we excluded patients with cancer, spinal infections, or open fractures. The ICD-9 codes used for inclusion and exclusion are listed in Table 1. Including all patients with even a single index visit for back pain implies a mix of patients with acute, subacute, and chronic pain.

Table 1.

ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes use to select or exclude patients

| Back Pain inclusion codes | |

| 721.3 | Lumbosacral spondylosis without myelopathy |

| 721.42 | Spondylogenic compression of lumbar spinal cord |

| 722.10 | Displacement of lumbar intervertebral disc without myelopathy |

| 722.32 | Schmorl’s nodes, lumbar |

| 722.52 | Degeneration of lumbar or lumbosacral intervertebral disc |

| 722.73 | Intervertebral disc disorder with myelopathy, lumbar |

| 722.83 | Postlaminectomy syndrome, lumbar |

| 722.93 | Other & unspecified disc disorder, lumbar |

| 724.02 | Spinal stenosis, lumbar |

| 724.2 | Lumbago; low back pain |

| 724.3 | Sciatica |

| 724.5 | Backache, unspecified |

| 724.6 | Disorders of sacrum |

| 738.4 | Acquired spondylolisthesis |

| 739.3, 739.4 | Somatic dysfunction, lumbar region or sacral region |

| 756.11 | Spondylolysis, lumbosacral region |

| 756.12 | Spondylolisthesis |

| 805.4, 805.6 | Vertebral fracture without spinal cord injury, closed, lumbar, sacrum, or coccyx |

| 846.0–846.9 | Sprains and strains of sacroiliac region |

| 847.2, 847.3 | Sprains and strains, lumbar or sacrum |

| Exclusion codes | |

| 140–239.9 | Neoplasms |

| 324.1 | Intraspinal abcess |

| 730–730.99 | Osteomyelitis |

| 805.1, 805.3, 805.5, 805.7, 805.9 | Open vertebral fractures |

| 03.2–03.29 | Chordotomy (procedure code) |

Defining Episodes of opioid use

For this purpose, we considered electronic pharmacy and medical record data for 6 months before and after an index visit (i.e., including data from 2003 and 2005). This time interval was used in the recognition that for many patients, the index visit in 2004 would not be their first back pain visit, as a relapsing course is common for low back pain. We sought to identify opioid use that might precede or follow the index visit by a relatively short interval.

Using definitions from Von Korff et al,16 opioid use was defined as “none”, “acute” (≤ 90 days), “episodic”, or “long-term” (≥120 days or > 90 days with 10 or more fills). Episodic use was for greater than 90 days, but less than 120 days, and with fewer than 10 fills of opioid medication. This was intended to identify opioid prescribing that was intermediate between acute and chronic use.

This classification considered cumulative opioid use during the year of observation, even though it might be discontinuous. Opioid use might represent a single or multiple opioid preparations (eg both a long-acting drug and a short-acting drug for “breakthrough” pain).

We considered use of the opioids listed in Table 1, and classified them as long or short acting as in the table. We also used the morphine equivalent calculations shown in the table, which is slightly adapted from Von Korff and colleagues.16

Mental Health Diagnoses

We searched medical records for one year prior to the index visit for any coded ICD-9-CM diagnoses for depression (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, 311), anxiety (300.0–300.09), post-traumatic stress disorder (309.81), or substance abuse (303.xx, 304.xx, 305.xx). The diagnoses were not based on standardized measures, but on clinicians’ judgments.

Measures of patient comorbidity and health care use

We recorded patient demographics, comorbidity score, smoking, and body-mass index (BMI). We also measured aspects of health care utilization, including co-prescription of sedative-hypnotics, emergency room (ER) visits, other clinic visits, and hospitalizations for the one year surrounding the index date (6 months before and 6 months after).

Sedative-hypnotic drugs were those identified using the Medi-Span Generic Product Identifier (GPI)17 or the American Hospital Formulary Service (AHFS) Drug Information compendium.18 These included benzodiazepines, barbiturates, so-called “z-drugs” (zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon), carisoprodol, and less frequently prescribed drugs (diphenhydramine, chloral hydrate, meprobamate, and others).

Comorbidity was measured using the RxRisk score, a pharmacy-based model designed to predict future health care costs based on patient age, sex, Medicare or Medicaid insurance coverage, and use of drugs closely linked to specific chronic conditions (e.g., biguanides, insulins, sulfonylureas for diabetes).19,20 A score is calculated from a regression model that weights each diagnosis according to its ability to predict future costs. To calculate scores, we used records for the one-year period prior to the index visit. RxRisk was developed in a managed care system with electronic records very similar to KPNW. For adults, the RxRisk calculation excludes analgesics, because they are prescribed with too much discretion to be appropriate for a payment adjustment model.19 In addition, we considered number of hospitalizations in the past year as a crude marker of illness burden.

Analysis

Because we hypothesized that certain lifestyle and mental health conditions would increase as duration of opioid use increased, we used the Cochrane-Armitage test for trend to compare proportions of patient characteristics, diagnoses, health care utilization, and prescription patterns across ordered categories of opioid use. This approach tests for an increasing or decreasing trend in patient characteristics and outcomes across ordered groups, as opposed to testing for any differences in proportions.

For continuous data, we used the Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric rank-sum test or univariable generalized linear models where appropriate. Multivariate analyses of dichotomous outcomes were conducted using logistic regression. For clinic visits, Poisson regression was used due to the non-normal distribution. Each model adjusted for patient age, sex, and comorbidity score. Depending on the analysis and study question, some models were also adjusted for use of sedative-hypnotics, number of hospitalizations, morphine dose at last dispensing before the index visit, and type of opioid (long- or short-acting). Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and all comparisons utilized a two-tailed p<.05 to define statistical significance.

RESULTS

Subjects and diagnoses

There were 26,014 patients with a diagnosis of low back pain who met our eligibility criteria. Of these, 15,830 (61%) received at least one opioid prescription in the year surrounding the index visit. Of those receiving opioids, 4,883 (18.8% of all patients with back pain) had an episode of long-term opioid use during that year.

Among all patients with back pain, mean age was 50.3 years (SD 16.6), and 56.5% were women. Among those with a recorded race (31% were missing), 89.3% were White, 3.2 % Black, 2.5% Asian, and 1.1% American Indian or Alaska Native; 4% self-reported other races. Among those reporting ethnicity (48% missing), 4.6% were Hispanic.

Most patients received non-specific diagnoses such as “low back pain”, or “sprains and strains” (78%). Another 12% had herniated discs, sciatica, degenerative discs, or spinal stenosis. The remainder received a variety of diagnoses (e.g. spondylolisthesis, closed vertebral fractures).

The most frequently prescribed opioids were hydrocodone with acetaminophen; oxycodone with acetaminophen; acetaminophen with codeine; oxycodone HCl, and morphine sulfate. These five preparations accounted for 92% of prescriptions.

Patient characteristics associated with opioid use

Table 2 divides the patients with back pain into 4 categories of opioid use: none, acute, episodic, or chronic. The table represents each patient only once, according to his or her longest episode of opioid use. Mean patient age rose with increasing duration of opioid use, as did the proportion of women. The comorbidity score also increased with increasing duration of opioid use (all p<0.001). Obesity and smoking were also associated with longer opioid use. Among long term opioid users, 52.6% were current or recent smokers, and 50.0% had a Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥30 (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Classification of Opioid Medications and Morphine Equivalent Conversion Factors per Milligram of Opioid*

| Major Group | Type of Opioid | Morphine Equivalent Conversion Factor/mg of Opioid |

|---|---|---|

| Short –acting, non-Schedule II | Propoxyphene (with or without aspirin/acetaminophen/ibuprofen) | 0.23 |

| Codeine+(acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or aspirin) | 0.15 | |

| Hydrocodone+(acetaminophen, ibuprofen, aspirin, or homatropine) | 1.00 | |

| Tramadol with or without aspirin | 0.10 | |

| Butalbital and codeine (with or without aspirin, ibuprofen, acetaminophen) | 0.15 | |

| Dihydrocodeine (with or without aspirin, ibuprofen, acetaminophen) | 0.25 | |

| Pentazocine (with or without aspirin, ibuprofen, acetaminophen) | 0.37 | |

| Short-acting, Schedule II | Morphine sulfate | 1.00 |

| Codeine sulfate | 0.15 | |

| Oxycodone (with or without aspirin, ibuprofen, acetaminophen) | 1.50 | |

| Hydromorphone | 4.00 | |

| Meperidine hydrochloride | 0.10 | |

| Fentanyl citrate transmucosal† | 0.125 | |

| Oxymorphone | 3.00 | |

| Long-acting, Schedule II | Morphine sulfate sustained release | 1.00 |

| Fentanyl transdermal‡ | 2.40 | |

| Levorphanol tartrate | 11.0 | |

| Oxycodone HCL controlled release | 1.50 | |

| Methadone | 3.00 |

Opioids delivered by pill, capsule, liquid, transdermal patch, and transmucosal administration were included. Opioids formulated for administration by injection or suppository were not included.

Transmucosal fentanyl conversion to morphine equivalents assumes 50% bioavailability of transmucosal fentanyl and 100-μg transmucosal fentanyl is equivalent to 12.5 to 15 mg of oral morphine.

Transdermal fentanyl conversion to morphine equivalents is based on the assumption that 1 patch delivers the dispensed micrograms/hour over a 24-hour day and remains in place for 3 days.

Mental Health Diagnoses

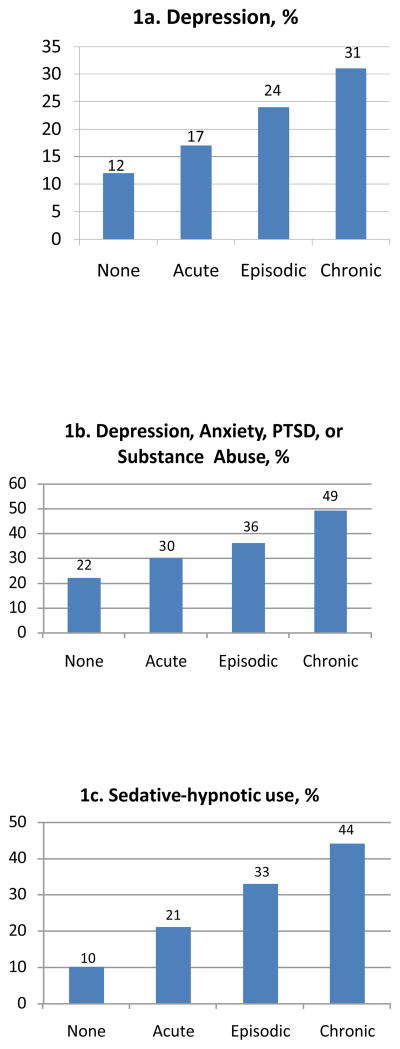

Diagnoses of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse increased in a monotonic trend across categories of increasing duration of opioid use (p<0.001, Figure 1 and Table 2). Among long-term opioid users, 31% had a diagnosis of depression, and 49% had at least one of these four mental health diagnoses. However, even patients with acute opioid use had a higher prevalence of depression than patients who had back pain with no opioid use (17.4% vs. 12.2%). This was true for each of the mental health diagnoses.

Figure 1.

Graphic presentation of proportions of patients with diagnoses of depression, any of 4 mental health diagnoses, or sedative hypnotic use, as a function of duration of opioid use

All of the associations between mental health diagnoses and duration of opioid use remained statistically significant after adjusting for patient age, sex, comorbidity, hospitalizations, and (in some cases) sedative-hypnotic use, in logistic regression models (Table 3). For depression and substance abuse, the two most common of these diagnoses, the odds ratios showed a monotonic pattern of association with duration of opioid use.

Table 3.

Use of long and short-acting opioids by duration of opioid use

| Acute opioid use | Episodic opioid use | Chronic opioid use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-acting opioid only (column %) | 98.3 | 85.2 | 59.4 |

| Long-acting opioid only (column %) | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Both long and short-acting opioid (column %) | 1.6 | 14.1 | 39.3 |

Health care use, co-prescribing of sedative hypnotics

Greater sedative-hypnotic use was associated with longer opioid use in a stepwise fashion, ranging from 10% among non-opioid users to 44.4% among chronic opioid users (Figure 1, Table 4). These stepwise associations persisted in multivariate models adjusted for age, sex, comorbidity, and number of hospitalizations. For example, the odds ratio for sedative-hypnotic use was 4.0 (95% CI: 3.65–4.39) for chronic opioid use as compared to none (Table 3). Benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed sedative-hypnotics: diazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam, clonazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam accounted for 80% of prescriptions. With the addition of hydroxyzine and zolpidem, these drugs accounted for 94% of sedative-hypnotic prescriptions.

Table 4.

Kaiser NW patient demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions according to duration of opioid use, 2004.†

| Characteristic | No opioids | Acute* opioids only | Episodic* opioid use | Chronic* opioid use | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n of subjects | 10,184 | 10,543 | 404 | 4,883 | - |

| Mean age, yearsa | 49.1 | 49.1 | 56.6 | 54.6 | <0.001 |

| Number (%) femaleb | 5,529 (54.3) | 5,847 (55.5) | 240 (59.4) | 3,071 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI, number (%) 30 or greaterb | 3,490 (36.8) | 4,525 (45.4) | 185 (47.2) | 2,403 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) Current smoker or recentb | 3,538 (37.4) | 4,620 (45.9) | 176 (46.3) | 2,476 (52.6) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with diagnosis of depression in previous yearb | 1,247 (12.2) | 1,839 (17.4) | 95 (23.5) | 1,526 (31.3) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with diagnosis of anxiety in previous yearb | 449 (4.4) | 594 (5.6) | 25 (6.2) | 573 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with diagnosis of PTSD in previous yearb | 54 (0.5) | 102 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 116 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with diagnosis of substance abuse in previous yearb | 946 (9.3) | 1,467 (13.9) | 60 (14.9) | 1,233 (25.3) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with any of the 4 mental health diagnosesb | 2,185 (21.5) | 3,108 (29.5) | 146 (36.1) | 2,405 (49.3) | <0.001 |

| Median Comorbidity score (RxRisk)c | 1,276 | 1,580 | 2,464 | 3,366 | <0.001 |

About 5% of patients had missing values for BMI and smoking status; the percentages displayed are calculated for non-missing cases.

“Acute” use was defined as ≤ 90 days. “Episodic” was defined as >90 days but < 120 days, and with fewer than 10 prescription fills. “Chronic” use was ≥ 120 days, or > 90 days with 10 or more prescription fills

Generalized linear model F-test

Cochrane-Armitage test for trend

Kruskal-Wallis test

Almost sixty percent of long-term opioid users received only short-acting opioids. Among the 40% who received long-acting opioids, nearly all received both long and short-acting opioids (Table 3). Among those with acute opioid use, 98% received only short-acting drugs.

Just over 36% of those with any opioid use had an Emergency Room (ER) visit during the study year, and about a third of these were associated with a back pain diagnosis (Table 4). An opioid prescription was filled within 5 days following 56% of ER visits. These percentages were similar among patients with any duration of opioid use. Emergency room use remained associated with opioid use after adjustment for age, sex, comorbidity, number of hospitalizations, and sedative hypnotic use. In this case, odds ratios for any duration of opioid use were similar and clustered around 2.0 (e.g., OR for chronic opioid use compared to no opioid use was 1.85, 95% CI 1.69, 2.02, p<0.01).

These patients with back pain made heavy use of other clinic services. The median number of all clinic visits in the year surrounding the index date was 18 for patients receiving chronic opioids, 8 for those not on opioids, and intermediate for those with acute or episodic opioid use (Table 4). In a Poisson regression, the trend for increasing clinic use remained associated with greater duration of opioid use. For example, even after adjustment for age, sex, comorbidity, and number of hospitalizations, patients receiving long term opioids had a 41% higher rate of clinic visits than patients with no opioid use (RR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.37,1.45). The number of different opioid prescribers also increased with increasing duration of opioid use (Table 4). Most patients were not seen in a specialty pain clinic: only 12% of even chronic opioid users had such a visit in the year surrounding the index visit.

Although only 3.6% of non opioid users were hospitalized during this time, over 20% of episodic or long-term opioid users were hospitalized (Table 4). In logistic regression models, the high risk of hospitalization among episodic and chronic opioid users persisted even after adjustment for age, gender, comorbidity score, and use of sedative-hypnotics. The odds ratio among those with acute use of opioids was 2.89 (95% CI: 2.55, 3.28), for episodic use, 4.70 (95% CI 3.57, 6.19) and for chronic use 3.90 (95% CI 3.40, 4.47).

DISCUSSION

Opioid prescribing was common among patients with back pain, and almost 20% received long-term opioids. Increasing duration of opioid use was associated with increasing age and comorbidity, suggesting that some opioid prescribing was related to conditions other than back pain, or in addition to back pain. Our data suggest that patients with back pain have a substantial comorbidity load that is associated with the duration of opioid use. Using data from the development of the RxRisk score,19 we can estimate that the mean RxRisk score of our patients receiving chronic opioid therapy was similar to that of age and sex-matched peers with coronary or peripheral vascular disease. The mean score of our “no opioid” group is about the same as that of patients with hypertension.

Increasing duration of opioid use was strongly associated with an increasing prevalence of mental health conditions (depression, anxiety, PTSD, or substance abuse): almost 50% of patients receiving long-term opioids had at least one of these diagnoses. Similarly, health habits (obesity, smoking) were associated with duration of opioid use. The rate of smoking among long-term opioid users was particularly high (over 50%).

Our data confirm other observations regarding mental health and chronic opioid use.11,12 However, our findings indicate that this association is not confined to long-term opioid users, in some threshold fashion, but is found in incremental stepwise fashion at all durations of opioid use. The causality of these associations is unclear. In a study of sequential surveys, depression and anxiety disorders at the first survey predicted a higher likelihood of opioid use at the second survey 3 years later.21 Thus it seems plausible that depression leads to more opioid use, though it may also be true that opioid use results in greater depression, or that these conditions are both associated with some confounding factor. Etiology aside, these associations may be of interest if they are merely predictive of long-term opioid use.

The wisdom of long-acting opioid use for chronic pain remains controversial, but is based on theoretical considerations of more consistent pain control and more normal sleep patterns, if dosing is less frequent.22 These considerations led to a KPNW guideline recommending long-acting drug use for chronic pain, and this was used as a quality indicator during the study period. Although use of long-acting opioids increased with duration of use, the frequent use (59%) of short-acting opioids among patients receiving long-term therapy supports Von Korff’s concept of “defacto” long-term prescribing.15 That is, many patients may become long-term opioid users through clinical inertia, with clinicians continuing to refill prescriptions for short-acting opioids and not considering a deliberate decision for long term use with informed consent and an opioid agreement. This is typically recommended after approximately 3 months of opioid prescribing.

We do not know the extent to which clinicians cautioned patients against concurrent use of sedative-hypnotics and opiates, but their co-prescribing presents a potential safety concern. Sedative-hypnotics in combination with opioids may increase the risk of over-sedation, overdose, and mortality. Furthermore, benzodiazepine use may predict subsequent use of opioids.23 The greater use of sedative-hypnotics with longer-term opioid use is contrary to the expectation based on expert recommendations, but has also been observed in other health care systems.14, 24, 25 It is unclear if the high use of sedative-hypnotics among long-term opioid users is a result of pre-existing anxiety or sleep disorders, sleep disorders induced by opioids, or a manifestation of “addictive personalities.” Some of these drugs -- specifically diazepam -- may have been used for muscle relaxant actions, suggesting an opportunity for clinician education.

Emergency room use was high among opioid users of any duration, though a minority of visits was associated with back pain. Nonetheless, more than half the ER visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid medication. These patients were also high utilizers of all clinic services. Some use is likely associated with monitoring and refills of opioids, but comorbidity and mental health concerns may also be important. As with clinic visits, the probability of hospitalization was associated with opioid use. Episodic or chronic use was associated with nearly 4-fold odds of being hospitalized, even after adjusting for age, gender, comorbidity, and sedative-hypnotic use. A minority of patients were seen a specialty pain clinic, suggesting that most, even with chronic opioid use, are managed in primary or emergency care. This was true even though access to pain clinic care was readily available in the form of pain management group visits throughout the practice region.

The number of different opioid prescribers increased with increasing duration of opioid use. This may suggest inadequate continuity of prescribing clinicians, but it may also be an inevitable consequence of long-term use, and may partially reflect access-to-care initiatives. For example, if a patient’s prescribing clinician is unavailable when medication supplies run low, the patient’s immediate needs would be met by other available clinicians (e.g. ‘doctor of the day’). This situation is more likely to occur for patients with greater use of services.

Strengths and Limitations

Our data have the advantages of representing a large population, many providers, and nearly complete capture of healthcare utilization. However, there are important limitations. The study population is representative of the racial/ethnic mix in the Portland metropolitan area, but under-represents minority populations. Thus, the results must be generalized with caution. Although every patient had back pain, we do not know the original indication for prescribing opioids. Clinical experience suggests that this may often be unclear for long-term opioid users, even when the full medical record is examined. Furthermore, many patients have multiple pain conditions, and it may be misleading to single out one diagnosis.24 We cannot know the degree to which the associations we found are causal or the direction of any causation. However, the graded association of many variables with the duration of opioid use strengthens an argument for causal associations. These findings may be useful for risk management even if they merely predict, rather than have an etiologic role.

In the case of diagnosed substance abuse, we cannot determine if these diagnoses are related to the prescribed opioids, other drugs, or both. To the extent that clinicians may use these diagnosis codes to indicate dependence on long-term prescribed opioids, they may be overused and misleading. Most patients with more than a few weeks of opioid therapy will experience withdrawal symptoms if opioids are discontinued, commonly referred to as “dependence.” This is distinctive from the compulsive and aberrant drug use of addiction, though this distinction is not always clearly made, and we cannot know from these data how the diagnosis of “substance abuse” is being used.

From pharmacy data alone, we cannot know if patients were receiving opioids from other sources, including illicit use. Many states have a statewide Prescription Monitoring Program that collects dispensing data from all pharmacies and helps to identify potential misuse, but such a system is not yet operational in Oregon. We did not assess whether opioid doses were increasing or decreasing during an episode of use. Our data are from 2004 and may not fully reflect current practice, but they establish a baseline against which future findings can be measured. Conclusions: These data suggest directions for improving the safety of opioid prescribing. The indications for combined opioid and sedative-hypnotic therapy should be scrutinized. Such co-prescribing has already become a target for quality improvement in some primary care practices.26 This concern might be part of an agenda for patient-physician shared decision-making before embarking on long-term opioid use.

Redoubling efforts to ensure prescriber continuity for long-term opioid users may also be important, to monitor the interaction of comorbid conditions and medications, and to reduce use of clinic, emergency department, and hospital care. If many visits are motivated by patients seeking their next prescriptions—rather than clinical complaints— system interventions or alternative treatment approaches may be warranted. The reasons for high clinic- and hospital-utilization deserve closer investigation, to determine other strategies for mitigating such use. Because opioid prescribing appears to be increasing most rapidly among patients with mental health and substance abuse diagnoses,11 primary care physicians may need to become more vigilant in screening for these conditions and addressing them prior to initiating opioid therapy.

Finally, these data suggest strategies for using electronic medical records to identify patients at high risk for long-term opioid use, drug misuse, or drug complications, and to support clinical decision-making. Such patterns may be unapparent from examining individual paper records. Others have begun to develop software to identify possible misuse or unsafe practices,27 and some decision aids are already being implemented in KPNW. This may represent a modern version of the approach advocated by Fry, who recommended examining one’s own practice population to identify patterns of illness and care that could lead to improvements in care.28

Table 5.

Logistic regression models for the associations of mental health diagnoses with duration of prescription opioid use. Tabled figures are odds ratios (95% Confidence intervals).†

| Depression | Anxiety | PTSD* | Substance Abuse | Sedative- hypnotic use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (reference category) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Acute‡ | 1.15 (1.06,1.25) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | 1.34 (0.96,1.88) | 1.44 (1.32, 1.57) | 1.94 (1.79, 2.11) |

| Episodic‡ | 1.35 (1.05, 1.74) | 0.95 (0.62, 1.45) | 0.31 (0.04, 2.28) | 1.56 (1.17, 2.08) | 2.99 (2.38, 3.75) |

| Chronic‡ | 1.49 (1.35, 1.64) | 1.44 (1.24, 1.66) | 2.07 (1.44, 2.96) | 2.77 (2.50, 3.08) | 4.00 (3.65, 4.39) |

PTSD= Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

All models adjusted for age, gender, comorbidity score, and number of hospitalizations in the past year. The models for depression and for substance abuse also adjusted for the use of sedative-hypnotics

“Acute” use was defined as ≤ 90 days. “Episodic” was defined as >90 days but < 120 days, and with fewer than 10 prescription fills. “Chronic” use was ≥ 120 days, or > 90 days with 10 or more prescription fills

Table 6.

Health care use and complications according to duration of opioid use

| Type of health care use | No opioids | Acute opioids only | Episodic opioid use | Chronic opioid use | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n of subjects | 10,184 | 10,543 | 404 | 4,883 | |

| Median opioid dose at last dispensing, morphine equivalenta | NA* | 30.0 mg | 20.0 mg | 30.0 mg | <0.001 |

| Median number of opioid prescribersa | NA* | 1 | 2 | 3 | <0.001 |

| Number (%) receiving sedative-hypnotic Rx in 6 mos before/after index visitb | 1,018 (10.0) | 2,163 (20.5) | 134 (33.2) | 2,166 (44.4) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with ER visit 6 mos. before/after index dateb | 1,725 (16.9) | 3,627 (34.4) | 148 (36.6) | 1,948 (39.9) | <0.001 |

| ER visit with back pain diagnosis, number (%) of patients with any ER visitb | 405 (23.5) | 1,246 (34.4) | 50 (33.8) | 535 (27.5) | 0.66 |

| Opioid prescription filled within 5 days of ER visit, % of patients with ER visitb | 1 (0.1) | 2,048 (56.5) | 85 (57.4) | 1,091 (56.0) | <0.001 |

| Median number of clinic visits of any type in 6 mos before/after index datea | 8 | 11 | 17 | 18 | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with any pain clinic visit in 6 mos before/after index dateb | 99 (1.0) | 227 (2.2) | 25 (6.2) | 585 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Number (%) with any hospitalization in 6 mos. before or after index date, %b | 364 (3.6) | 1,126 (10.7) | 87 (21.5) | 1,012 (20.7) | <0.001 |

Not applicable. This category not included in tests of statistical significance.

Kruskal-Wallis test

Cochrane-Armitage test for trend

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible with support from the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI), grant number UL1 RR024140 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Footnotes

The authors report no relevant commercial conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP, Sullivan MD. Epidemiology of regular prescribed opioid use: results from a national, population-based survey. J Pain Sympt Mgmt. 2008;36:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eriksen J, Sjogren P, Bruera E, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Critical issues on opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: an epidemiological study. Pain. 2006;125:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, Becker WC, Morales KH, Kosten TR, Fiellin DA. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 207(146):116–127. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109:514–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Comstock BA, Hollingworth W, Sullivan SD. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299:656–664. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin GM, Mai J, Wickizer T, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Grant L. Opioid dosing trends and mortality in Washington State workers’ compensation, 1996–2002. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(2):91–9. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Hey L. Patterns and trends in opioid use among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004;29:884–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200404150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerzan JT, Morden NE, Soumerai S, et al. Trends and geographic variation of opiate medication use in state Medicaid fee-for-service programs, 1996 to 2002. Med Care. 2006;44:1005–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228025.04535.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:618–27. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan M-Y, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP Study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:1–8. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b99f35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129:355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasan AD, Davar G, Jamison R. The association between negative affect and opioid analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain. Pain. 2005;117:450–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermos JA, Young MM, Gagnon DR, Fiore LD. Characterizations of long-term oxycodone/acetaminophen prescriptions in veteran patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2361–66. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Volinn E, Loeser JD. Use of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) to identify hospitalizations for mechanical low back problems in administrative databases. Spine. 1992;17:817–825. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199207000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Korff M, Saunders K, Ray GT, et al. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:521–7. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318169d03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed July 15,2010];Master Drug Data Base v 2.5. http://www.medi-span.com/master-drug-database.aspx.

- 18.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [accessed July 15,2010];AHFS Drug Information. http://www.ahfsdruginformation.com/products_services/di_ahfs.aspx.

- 19.Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Meenan RT, Bachman DJ, O’Keefe Rosetti MC. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk Model. Medical Care. 2003;41:84–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farley FJ, Harley CR, Devine JW. A comparison of comorbidity measurements to predict healthcare expenditures. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2087–93. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalso E, Allan L, Dobrogowski J, et al. Do strong opioids have a role in the early management of back pain? Recommendations from a European expert panel. Current Med Res Opinion. 2005;21:1819–28. doi: 10.1185/030079905X65303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skurtveit S, Furu K, Bramness J, Selmer R, Tverdal A. Benzodiazepines predict use of opioids – a follow-up study of 17,074 men and women. Pain Medicine. 2010;11:805–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Carr TP, Deyo RA, Dobscha SK. Clinical characteristics of veterans prescribed high doses of opioid medications for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010 Aug 27; doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boudreau D, von Korff M, Rutter CM, et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmocoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:1166–75. doi: 10.1002/pds.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper S, Bruno R, Sharpe M, Tahmindjis A. Alprazolam prescribing in Tasmania: a twofold intervention designed to reduce inappropriate prescribing and concomitant opiate prescription. Australasian Psych. 2009;17:300–305. doi: 10.1080/10398560902998626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parente ST, Kim SS, Finch MD, Schloff LA, Rector TS, Seifeldin R, Haddox JD. Identifying controlled substance patterns of utilization requiring evaluation using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:783–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fry J. Common Diseases: their nature, incidence, and care. 4. Lancaster: MTP press Limited; 1985. pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]