Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the perceptions of cigarette packaging and the potential impact of plain packaging regulations. The hypothesis was that the branded cigarette packages would be rated more positively than the corresponding plain packs with and without descriptors.

Design

Between-subjects experimental online survey. Male and female participants were separately randomised to one of the three experimental conditions: fully branded cigarette packs, plain packs with descriptors and plain packs without descriptors; participants were asked to evaluate 12 individual cigarette packages. The participants were also asked to compare five pairs of packs from the same brand family.

Setting

Norway.

Participants

1010 youths and adults aged 15–22.

Primary outcome measures

Ratings of appeal, taste and harmfulness for individual packages. Ratings of taste, harm, quality, ‘would rather try’ and ‘easier to quit’ for pairs of packages.

Results

Plain with and without descriptors packs were rated less positively than the branded packs on appeal (index score 1.63/1.61 vs 2.42, p<0.001), taste (index score 1.21/1.12 vs 1.70, p<0.001) and as less harmful (index score 1.0.34/0.36 vs 0.82, p<0.001) among females. Among males, the difference between the plain with and without descriptors versus branded condition was significant for appeal (index score 2.08/1.92 vs 2.58, p<0.005) and between the plain without descriptors versus branded condition for taste (index score 1.18 vs 1.70, p<0.00). The pack comparison task showed that the packs with descriptors suggesting a lower content of harmful substances, together with lighter colours, were more positively rated in the branded compared with the plain condition on dimensions less harmful (β −0.77, 95% CI −0.97 to −0.56), would rather try (β −0.32, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.14) and easier to quit (β −0.58, 95% CI −0.76 to −0.39).

Conclusions

The results indicate that a shift from branded to plain cigarette packaging could lead to a reduction in positive perceptions of cigarettes among young people.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, SOCIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study design provides a qualitative overview of evaluations of different branded cigarette packs, in addition to the results on differences in perceptions of branded and plain packs.

The study provides insight into the significance of cigarette packaging in a context where marketing of tobacco and extensive use of innovative package design is already highly regulated.

Respondents in the three conditions did not differ statistically from each other in terms of age, smoking status or gender, but other, unmeasured factors could have influenced the variation found between the groups.

Introduction

In the process of building a brand, it is crucial to create the right product name and to develop a visual motif or logo that will be imprinted onto consumers’ minds as associations with the brand that will differentiate it from the competing products in the market.1 In the marketing of tobacco, such ‘cues’ related to brand imagery are typically coded into the product's packet design and colour scheme. Studies of documents from the tobacco industry have shown how cigarette branding has been used to target a particular consumer group, how branding may increase the appeal of smoking,2–4 and how considerable efforts have been put into developing cigarette packet designs that attract the consumers.5

Particularly, in dark markets, cigarette pack design has become a main vehicle for tobacco marketing. Colouring and colour descriptors are key measures used for communicating messages about the product, for example, to target a particular gender or to portray smoking in line with the desired brand image.3 Shades of the same colour and the proportion of white space on the package are commonly used to distinguish between the variants of the same brand, with darker colours generally used to portray a stronger, full-flavoured product and lighter colours to communicate a brand of lower tar and nicotine content. As the colour scale moves towards white, associations with cleanliness and a healthy product are targeted.5 Brand descriptors and images have also been important elements in the tobacco industry's strategy of falsely reassuring consumers about the potential harm of their products.6 Cigarettes labelled ‘light’ or ‘mild’ have been marketed as less harmful to health due to reductions in toxin exposure, an assertion that has been thoroughly repudiated by epidemiological data indicating that smoking these products has little or no health benefit,7 as smokers tend to compensate for reduced delivery of nicotine. As a result of this, tar delivery increases, effectually cancelling out the presumed benefits of ‘low-tar’ cigarettes.8 Research has shown that many smokers falsely believe that cigarettes labelled ‘light’ or ‘mild’ actually deliver less tar and are less harmful to smokers.9 Furthermore, regulating the use of such descriptors does not seem to be sufficient to correct these beliefs. Studies from jurisdictions where regulations on misleading descriptors have been implemented have exposed that many smokers continue to believe that some cigarette brands are less harmful than others, and that these beliefs are associated with descriptive words and elements of package designs that have yet to be prohibited, including the names of colours.10 11

In order to limit the package design opportunity of communication between the tobacco producers and the consumers (and potential consumers in particular), several jurisdictions have considered regulations on package design,12 and Australia was the first country to implement plain packaging of tobacco products, in December 2012. While it is still early to draw conclusions about the real-life effect of plain packaging, a growing body of experimental evidence supports the potential public health benefits of plain packaging. Studies have, for example, demonstrated that pack colours and brand imagery such as symbols and graphics can influence consumers’ perceptions of the risk involved in using tobacco products,13 and that the removal of brand images from cigarette packaging can reduce the appeal of packs and products.14–16 Experimental research has also indicated that plain packaging can significantly reduce false beliefs about health risks and ease of quitting,13 17 promote cessation behaviour18 and increase the salience of health warnings.19 Recent research has also indicated that removing the descriptors from plain packs can decrease the ratings of appeal, taste and smoothness further, and also reduce the associations with positive attributes.20 21

In Norway, qualitative studies have indicated that the power of tobacco branding remains strong,22 despite strict regulations on marketing. A relatively limited array of tobacco brands and pack designs are for sale, probably due to the size of the market as well as the regulatory environment. Since 1975, when all tobacco advertising was banned, a range of additional tobacco marketing restrictions have been implemented, including restrictions on selling cigarette packages that because of ‘unconventional design or appearance can lead to increased sales’ (1995), misleading brand descriptors (2003), and a complete point of sale display ban (2010). Combined with consistently high tobacco tax levels and other important judicial restrictions such as the ban on indoor smoking in public areas in 2004, these regulations on tobacco marketing have probably contributed to the reductions in daily smoking prevalence in the recent years, as well as influenced the characteristics of the tobacco market.

The aim of the current study was to examine the perceptions of cigarette packaging among young adults in a context where marketing is highly restricted and where pack designs are less innovative than in many other jurisdictions. More specifically, the aim was to examine the impact of colour variations, imagery and brand descriptors on perceptions of appeal, taste, health risks and ease of quitting, the effect of removing these elements (ie, plain packaging) on the same variables, and individual differences in perceptions of packaging.

Methods

One thousand and ten male and female smokers and non-smokers, aged 15–22 years, were recruited from TNS Gallup's online participant panel during 2011. The panel is representative of the population with regard to demographical variables; the panelists were invited into the survey with age and gender as the inclusion criteria. All participants were provided with remuneration according to Gallup's standard procedures. This study received full clearance from the Norwegian Data Protection Official for Research, including ethical evaluation (project number 34 433). The data collection had an experimental, between-subjects design; participants were randomly assigned to one of three pack conditions: branded, plain with descriptors or plain without descriptors, as illustrated in figure 1. While the participants in the branded condition 1 were shown images of standard, fully branded cigarette packages, those assigned to the plain with descriptors condition 2 viewed images of the same packs digitally altered to remove brand imagery and colours, while descriptors (ie, ‘rough taste’ or ‘white’) remained on a plain, grey package. In the plain without descriptors condition 3, participants were shown packages similar to condition 2, in which descriptors had also been removed.

Figure 1.

Examples of the three versions of cigarette packs.

The studies mandating a grey/olive plain pack colour made before the implementation of the Australian plain packaging legislation had not been carried out at the time we designed this study. The grey plain pack colour was chosen based on a common sense evaluation of grey as a colour signifying ‘indistinctive’ and unappealing. The cupboards used to cover the tobacco products in shops after the point-of-sale display ban was implemented in Norway usually has a similar grey colour,23 underlining perhaps the cultural connotations of this colour in the local context that this study was undertaken in.

All packages included in the study were purposely selected from leading international and Scandinavian brand names to reflect the key dimensions of interest in terms of the brand descriptors and brand imagery. For instance, brands that featured different colour descriptors (eg, red vs gold), and flavour descriptors (eg, rounded taste vs rich taste) were selected. Packages that featured different brand imagery were also selected, including the use of different colours (eg, red vs white), and also packages of different sizes (10s and 20s).

English and Norwegian language descriptors were present among the selected brands. English is a second language spoken among a large majority of the population in Norway, and in particular among young people. It is thus unlikely that the respondents had problems understanding the descriptor words in any of the languages. There were no statistically significant differences in the age, gender or smoker distributions of the participants according to pack condition. Overall, 79.5% were non-smokers, and 41.8% of the participants were male. The age distribution showed that 16.6% were 15–17 years old, 44.7% were 18–20 years old and 38.7% were 21–22 years old.

The participants were given two tasks: the first task was an individual pack rating, and included 12 individual packs to be rated on perceived appeal, taste and harmfulness. In this section, males and females were shown different pack selections, the males’ selection consisting of supposedly ‘male-oriented’ packs, and the females’ selection consisted of supposedly ‘female-oriented’ packs. The distinction between male and female brands was based on previous qualitative studies from Norway,22 16 as well as presumptions about gender-coded colouring (eg, lighter pack=feminine) and descriptors (eg, rough taste=masculine). Four of the brand varieties were the same for both genders. Images of all packs included are shown in tables 1 and 2. An automatic function securing that the packs were presented to individual respondents in a random order was programmed into the setup of the survey. The second task was the direct pack comparison task. In this task, the participants were shown five pairs of packs from the same brand family with the intent of highlighting the role of descriptors and brand imagery in communicating the relative differences between the brands. Each pair, made up of packs from the individual pack selections, included a ‘regular’ brand variety, typically a darker pack containing a product with an average or somewhat high tar and nicotine content, and a ‘lighter’ variety, typically in a lighter package and with lower nominal levels of tar and nicotine. The paired packs were: Prince Rich Taste versus Rounded Taste, Marlboro Red versus Gold Original, Kent Original versus HD Taste System, Lucky Strike Original versus Blue and Petteroes Original versus Lys blå (Pale blue). The participants were asked to evaluate the two packages against each other on variables aimed at tapping perceptions of health risk and addictiveness. The pack comparison task was identical for males and females, and there were only two experimental groups: branded and plain with descriptor. This was achieved by combining the participants in conditions 3 (plain without descriptors) and 2 (plain with descriptors) into one group for this section of the questionnaire.

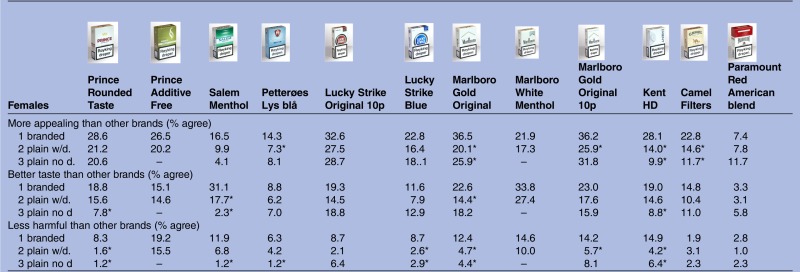

Table 1.

Female ratings for individual cigarette packages by experimental condition (n condition 1=221, n condition 2=195, n condition 3=172)

|

Values with * indicate significant differences at the p<0.05 level between branded and plain conditions for individual packages in logistic regression models adjusting for age, smoking status and health risk awareness index score.

w/d, with descriptors; no d., no descriptors.

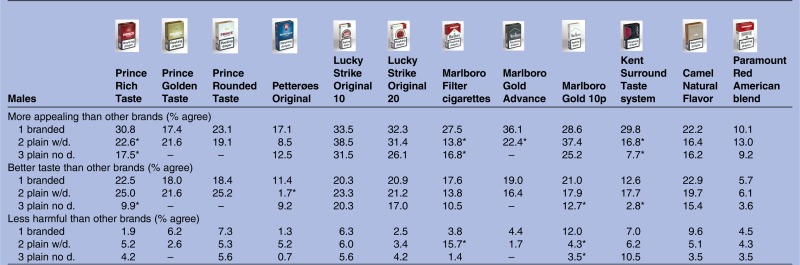

Table 2.

Male ratings for individual cigarette packages by experimental condition (n condition 1=163, n condition 2=118, n condition 3=143)

|

Values with * indicate significant differences at the p<0.05 level between branded and plain conditions for individual packages in logistic regression models adjusting for age, smoking status and health risk awareness index score.

w/d, with descriptors; no d., no descriptors.

Measures

The participants were asked to indicate how they perceived each individual pack with regard to three characteristics: appeal, taste and harmfulness. Questions were phrased as global comparisons, in the form ‘Compared with other brands, how appealing (tasty, harmful) do you think this brand of cigarettes is?’ The respondents were presented with four answer categories, in the form of: this brand is less appealing (tasty, harmful), no difference, or more appealing (tasty, harmful) and ‘do not know’. Brandwise, perceived characteristics were recoded into binary variables contrasting those who answered that the brand was more appealing/tasty/less harmful (1), with the rest (0). All binary categories were subsequently summed together, creating the sum-score indexes for each brand characteristic across all packs, with higher scores signifying more positive characterisations.

In the direct pack comparison task, participants were asked to indicate which, if any, of the two packs in each pair they believed to taste better, to be less harmful, to be of better quality, and to be easier to quit. They were also asked which of the two they would rather try. After recoding the answers into binary variables contrasting those who chose the ‘lighter’ pack (1) with the rest (0), additive indexes were constructed for each dimension, across all pairs and both genders.

The additional variables used in the analyses were age (coded into three age groups), smoking status and perceptions of risk to health from smoking. Smokers were defined as those who had smoked at all during the last 30 days. Respondents were asked whether they believed or knew that smoking could cause 12 different diseases: lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, mouth cancer, cancer of the larynx, emphysema, gangrene, impotence for male smokers, wrinkles and aging of the skin, harm to unborn children, lung cancer for non-smokers breathing other people's cigarette smoke, and death. Response options were: yes, no, and do not know. All positive answers were summed together to create a health risk awareness index. For the logistic regression analyses, the index was recoded into a variable with three values (0–4, 5–8, 9–12).

Analysis

The analyses tested two primary hypotheses: (1) individual fully branded packages will be rated as significantly more appealing, better tasting and less harmful than the corresponding plain packs with and without descriptors. (2) In a direct comparison of ‘regular’ and ‘lighter’ packs from the same brand family (eg, Marlboro vs Marlboro Gold), the lighter pack will more often be perceived as more appealing, better tasting and less harmful in the branded condition than in the plain (with descriptors only) condition. In the analyses of individual packages, logistic regression models were used to test for differences between the experimental conditions, adjusting for age, smoking status and health risk awareness.

In the instances where the pack selection included more than one variety of a specific brand, the condition 3 version of the second variety pack was altered to white (2 packs in females’ selection) or black (3 packs in males’ selection) instead of the standard grey. This was carried out in order to make the task meaningful for the respondents assigned to condition 3, who would otherwise have been asked to differentiate between identical packs. However, as these alternative plain packs made the results difficult to interpret, they are excluded from the presentation of individual scores in tables 1 and 2. In the calculation of mean pack rating index scores presented in table 3, the packs that were black or white in condition 3 were excluded for all conditions. This index is thus calculated from scores on 10 packages for females and nine packages for males.

Table 3.

Index scores of perceived positive brand characteristics by gender and experimental condition

| Experimental condition | Mean score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls |

Boys |

|||||

| Appeal | Taste | Less harmful | Appeal | Taste | Less harmful | |

| Branded packs | 2.42 | 1.70 | 0.82 | 2.58 | 1.70 | 0.52 |

| Plain, with descriptors | 1.63** | 1.21** | 0.34** | 2.08* | 1.60 | 0.56 |

| Plain, no descriptors | 1.61** | 1.12** | 0.36** | 1.92* | 1.18* | 0.41 |

Values with (*) indicate significant difference at the p<0.001 (**) or 0.05(*) level between experimental conditions for each smoker trait in linear regression models adjusting for age, smoking status and health risk awareness index score.

Linear regression analysis was used to test the differences in index scores between the conditions, adjusting for age, smoking status and health risk awareness. Linear regression analysis was also used to test significant differences between the conditions on pack comparison index scores, adjusting for age, gender, smoking status and the level of health risk awareness. All analyses were conducted in SPSS V.19.0.

Results

Individual pack ratings

Table 1 shows females’ ratings of brand appeal, taste and harmfulness for individual packs. The highest appeal ratings in the branded condition were given for Marlboro Gold Original packs (10s and 20s) and Lucky Strike Original 10s. The packs that were given the highest ratings for taste by females were the two menthol brands: Salem and Marlboro White Menthol. On the harmfulness dimension, Prince Additive Free was most often rated positively by females, followed by Kent HD, Marlboro White Menthol and Marlboro Gold Original 10s. These are all brands that are sold in packets with colours close to white on a scale from darker to lighter packs. The highest occurrence of significant differences between the conditions was found for harmfulness.

Table 2 shows males’ individual pack ratings. In the branded condition, the pack rated as most appealing was the black Marlboro Gold Advance, followed by Lucky Strike Original (10s and 20s). The brand most often evaluated as tasting better than others was Prince Rich Taste and Camel Natural Flavor, both of which had descriptors focusing on flavour. Males most often rated white Marlboro Gold 10 as less harmful than other brands, followed by Camel Natural Flavor. Compared with the situation for females, significant differences between the conditions were somewhat less common for males. This difference between the genders was particularly noticeable for perceived harmfulness, where the analysis showed significant differences between the conditions only for two packages, compared with seven among females.

Table 3 shows the index scores for appeal, taste and harmfulness by gender and experimental condition. Linear regressions were conducted with experimental condition as the main independent variable and each of the characteristics of appeal, taste and harmfulness as the dependent variable, adjusting for age, smoking status and health risk awareness. Plain packages received significantly fewer positive ratings from females on all three dimensions. Among males, the difference between the branded and both plain conditions was significant for perceptions of appeal. The difference between branded and plain, no descriptors was also significant for taste.

Pack comparisons

Statistical differences between the conditions on the index score summing up ‘light’ pack choices across all pairs were observed for the dimensions ‘less harmful’, ‘would rather try’ and ‘easier to quit’, with larger proportions answering that they believed that the lighter pack variant fitted these descriptions in the branded compared to the plain condition (table 4). Smoking status was a significant confounder in all these models, implying that the smokers more often chose the light pack as fitting these descriptions. Risk awareness contributed significantly to explain the pack choice for harmfulness, gender had an impact on the willingness to try, and age influenced the perceptions of which pack was easiest to quit.

Table 4.

Linear regression predicting viewing the lighter coloured pack in a pair of two brand variants more positively regarding of taste, harm, quality, would rather try and easier to quit

| Plain (ref: branded) | Taste better | Less harmful | Better quality | Would rather try | Easier to quit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | −0.12 | −0.77 | 0.04 | −0.32 | −0.58 |

| 95% CI for β | −0.29 to 0.06 | −0.97 to −0.56 | −0.11 to 0.18 | −0.50 to −0.14 | −0.76 to −0.39 |

| p Value | 0.191 | <0.001 | 0.627 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Moderators (β, significance) | Gender (ref: male) −0.14 (p<0.001) | Smoking status (ref: non-smoker) 0.77 (p<0.001) Risk awareness index 0.05 (p=0.049) |

Age (ref: between 15 and 18) −0.11 (p=0.004) | Gender (ref: male) −0.15 (p<0.001) Smoking status (ref: non-smoker) 0.13 (p<0.001) |

Age (ref: between 15 and 18) −0.10 (p=0.012) Smoking status (ref: non-smoker) 0.15 (p<0.001) |

Model adjusting for the following covariates: age, smoking status, gender and risk awareness (β and p value of significant covariates listed in table).

Discussion

In this study, pack design influenced the way participating youths and young adults perceived cigarette brand characteristics. Among girls, the analysis across all individual packages showed that the branded packages were significantly more often rated as appealing, as tasting better and as less harmful than the plain packages with and without descriptors. Boys rated branded packages more positively compared with plain packages with and without descriptors for appeal, and more positively compared with plain packages without descriptors for taste. The pack comparison task indicated that the use of descriptors suggesting a lower content of harmful substances, together with light colours, affected the consumers’ perceptions of tobacco products. The ‘lighter’ packs were significantly more often selected as being less harmful, easier to quit and appealing (a product I would rather try) in the branded condition than in the plain condition. The strongest of these effects was found for perceptions of a less harmful product.

The pattern of how individual packages were evaluated in the branded condition clearly suggested that colour, design elements and descriptors act together in a way that forms consumers’ perceptions of product qualities. Females generally perceived white packs as more appealing while males typically preferred the darker packs, indicating that the tobacco producers’ strategies for building associations and identification4 5 are successful also in a country where the marketing of tobacco products is very restricted. Results regarding perceptions of taste indicated that the descriptors were an important dimension; brands more positively evaluated were those with flavour additives (menthol) or other references to flavour (natural flavour, rich taste). All packs in light colours or with descriptors such as ‘additive free’ were more positively rated regarding harmfulness.

Interestingly, even though the general pattern as expected was that removing the descriptors from plain packages decreased the positive perceptions of packs, the plain without descriptor packs were in some of the analyses of individual packages rated more positively than the plain packs with descriptors. This pattern appeared to be most noticeable for strong brand names such as Marlboro or Lucky Strike. Other studies of plain packaging and descriptors have reported similar patterns20 21 and inferred that brand family names may become relatively more important in distinguishing between the brands and promoting appeal in the absence of brand imagery and descriptors.

The typically ‘feminine’ cigarette packs sold in other countries, such as packs that look like lipstick boxes or packs with typically feminine names such as, for example, Vogue or Slims, are not for sale in Norway, perhaps partly due to the regulations on ‘unconventional’ packaging. Still, Norwegian youth seem to have found their own way of differentiating between masculine and feminine packs. We observed that the packs that are likely to appear more gender-neutral in countries where such packs are at sale, for example, Marlboro Original Gold20 seem to be popular among girls in Norway, probably partly because of a position as feminine.22 This illustrates the power of packaging to communicate messages that allow consumers to identify with and differentiate between the brands, also when more conspicuous designs and elaborate elements such as pack shape, opening methods or shape of the cigarette are not being used.

There was a tendency for males to demonstrate somewhat more stable views regardless of condition. This could indicate that pack design is less important for males’ perceptions of brand characteristics; perhaps males are less interested in, and therefore less influenced by, the design of cigarette packs? It has been documented that the tobacco industry has made particular efforts to design the cigarette packages more attractive for girls.4 On the other hand, the shortage of significant differences between conditions among males could be the result of a very high degree of awareness of the differences between brand images, so that the brand associations stay on after only the brand name remains to identify the product. Previous research has concluded both in favour24 and against25 the significance of gender on perceptions of pack design and plain packaging.

An intrinsic weakness in the study design is that all participants would have been quite familiar with the design of the branded cigarette packs, and may have formed ideas about the products and their qualities before they took part in the study. This possibility is augmented by the fact that the packs included in the samples tended to be quite popular and well known. However, if the respondents in the plain conditions let former ideas about the brand characteristics influence their answers, it is likely that this would have worked to diminish the difference between the results in the different conditions more than if the participants were neutral from the start. Another possible limitation of this study is that the colour used to represent plain packaging may have influenced the respondents’ perceptions in a different way than intended. Studies from other countries evaluating the suitability of different colours have, for example, concluded that grey is perceived less negatively than brown.24 This concern is, to some extent, reduced by findings from qualitative studies indicating that grey plain cigarette packages are perceived negatively in Norway.16 The between-subjects design also carries with it some challenges, predominantly the risk of uncontrolled variation between the groups, or in this case, between the conditions. Fortunately, the groups did not differ statistically from each other in terms of age, smoking status or gender, but it is of course possible that other, unmeasured factors could have influenced the variation found between the groups.

In conclusion, the results of this study point to how packages communicate messages that allow consumers to identify with and differentiate between cigarette brands, and thus are essential in the processes branding works through.26 The results indicate further that a shift from branded to plain cigarette packaging could lead to a reduction in positive perceptions of cigarettes among adolescents, also in a context where marketing of tobacco as well as extensive use of innovative pack design to attract the consumers is already highly regulated. The result that the respondents so clearly make distinctions regarding harmfulness and ease of quitting between the brand varieties based upon colours and descriptors confirms the findings from a previous qualitative research in Norway16 and points towards the conclusion that cigarette descriptors such as ‘rounded taste’ (in contrast to ‘rough taste’) and colour codes such as ‘gold’ or ‘pale blue’ are perceived in a similar way as the prohibited terms ‘light’ and ‘mild’. The use of these terms thus appears to violate the guidelines of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control treaty, which forbids information that directly or indirectly creates the false impression that a particular tobacco product is less harmful than other tobacco products.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JS designed the study, performed the main part of the analysis and drafted the paper. IL performed some of the analysis and took part in drafting the paper.

Funding: None received.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No unpublished data from this study are available after the publication of his study.

References

- 1.Carter SM. The Australian cigarette brand as product, person and symbol. Tob Control 2003;12:iii79–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wayne GF, Connolly G. How cigarette design can affect youth initiation into smoking: camel cigarettes 1983–93. Tob Control 2002;11:i32–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson SJ, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Emotions for sale: cigarette advertising and women's psychosocial needs. Tob Control 2005;14:127–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction 2005;100:837–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, et al. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2002;11(Suppl 1):i73–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. The dark side of marketing seemingly ‘light’ cigarettes: successful images and failed fact. Tob Control 2002;11:18–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thun MJ, Burns DM. Health impact of ‘reduced yield’ cigarettes: a critical assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Tob Control 2001;10:4–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hecht SS, Murphy SE, Carmella SG, et al. Similar uptake of lung carcinogens by smokers of regular, light, and ultralight cigarettes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:639–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson N, Weerasekera D, Peace J, et al. Misperceptions of ‘light’ cigarettes abound: national survey data. BMC Public Health 2009;9:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borland R, Fong GT, Yong HH, et al. What happened to smokers’ beliefs about light cigarettes when ‘light/mild’ brand descriptors were banned in the UK? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Tob Control 2008;17:256–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutti S, Hammond D, Borland R, et al. Beyond light and mild: cigarette brand descriptors and perceptions of risk in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Addiction 2011;106:1166–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford A, Moodie C, Hastings G. The role of packaging for consumers products: understanding the move towards ‘plain’ tobacco packaging. Addict Res Theory 2012;20:339–47 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D, Dockrell M, Arnott D, et al. Cigarette package design and perceptions of risk among UK adults and youth. Eur J of Public Health 2009;19:631–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakefield MA, Germain D, Durkin SJ. How does increasingly plainer cigarette packaging influence adult smokers’ perceptions about brand image? An experimental study. Tob Control 2008;17:416–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moodie C, Ford A, Mackintosh AM, et al. Young people's perceptions of cigarette packaging and plain packaging: an online survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheffels J, Sæbø G. Perceptions of plain and branded cigarette packaging among Norwegian youth and adults: a focus group study. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:450–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoek J, Gendall P, Gifford H, et al. Tobacco branding, plain packaging, pictorial warnings, and symbolic consumption. Qual Health Res 2012;22:630–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoek J, Wong C, Gendall P, et al. Effects of dissuasive packaging on young adult smokers. Tob Control 2011;20:183–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munafo MR, Roberts N, Bauld L, et al. Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers. Addiction 2011;106:1505–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White CM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF, et al. The potential impact of plain packaging of cigarette products among Brazilian young women: an experimental study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond D, Daniel S, White CM. The effect of cigarette branding and plain packaging on female youth in the United Kingdom. J Adolesc Health, 2012;2:151–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheffels J. A difference that makes a difference: young adult smokers’ accounts of cigarette brands and package design. Tob Control 2008;17:118–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffels J, Lavik R. Out of sight, out of mind? Removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Norway. Tob Control 2013;22:e37–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moodie C, Ford A. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of cigarette pack innovation, pack colour and plain packaging. Mark Public Policy Aust Mark J 2011;19:174–80 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gendall P, Hoek J, Edwards R, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of how young adults perceive tobacco brands: implications for FCTC signatories. BMC Public Health 2012;12:796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulberg J. Integrating corporate branding and sociological paradigms: a literature study. J Brand Manage 2006;14:60–73 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.