Abstract

Scope

Metabolic syndrome has become an epidemic and poses tremendous burden on the health system. People with metabolic syndrome are more likely to experience cognitive decline. As obesity and sedentary lifestyles become more common, the development of early prevention strategies are critical. In this study, we explore the potential beneficial effects of a combinatory polyphenol preparation composed of grape seed extract, Concord purple grape juice extract and resveratrol, referred to as Standardized Grape Polyphenol Preparation (SGP), on peripheral as well as brain dysfunction induced by metabolic syndrome.

Methods

We found dietary fat content had minimal effects on absorption and metabolites of major polyphenols derived from SGP. Using a diet-induced animal model of metabolic syndrome (DIM), we found that brain functional connectivity and synaptic plasticity are compromised in the DIM mice. Treatment with SGP not only prevented peripheral metabolic abnormality but also improved brain synaptic plasticity.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that SGP comprised of multiple bioavailable and bioactive components targeting a wide range of metabolic syndrome-related pathological features provides greater global protection against peripheral and central nervous system dysfunctions and can be potentially developed as novel prevention/treatment for improving brain connectivity and synaptic plasticity important for learning and memory.

Keywords: metabolic syndrome, polyphenols, Standardized Grape Polyphenol Preparation, synaptic plasticity

1 Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by a mosaic of conditions such as obesity, hyperglycemia and impaired insulin sensitivity (also known as type 2 diabetes), hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. It is by far the most prevalent disease in the world. Based on the National Health Statistics Reports [1], approximately 34% of adults in the United States meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, the risk and prevalence of metabolic syndrome increases with age. People 40-59 years of age are approximately three times more likely to have metabolic syndrome than those 20-39 years of age [1]. Despite national and international efforts focused on prevention of metabolic syndrome and its underlying diseases/disorders, its prevalence is still rising.

Observational studies have identified a wide range of potentially modifiable risk factors for cognitive dysfunction and possibly dementia. Metabolic syndrome, among other lifestyle factors, is potentially associated with an increased risk for age-related cognitive deterioration [2-4]. Three longitudinal studies conducted by Yaffe [5], Komulainen [6] and Dik [7] independently showed that metabolic syndrome, as a whole, is related to a higher risk for cognitive decline. A meta-analysis performed by Profenno and colleagues [8] reviewed thirteen longitudinal epidemiological studies that examined the association between metabolic syndrome and dementia, and found that obesity and diabetes significantly and independently increase one’s risk for dementia.

Based on these epidemiological data coupled together with an ageing population in many western countries, the potential impact of metabolic syndrome on cognitive dysfunction has serious health care implications. Therefore, developing a novel, safe and efficacious preventative and/or therapeutic intervention for metabolic syndrome and resulting brain impairments is of fundamental importance.

Accumulating evidence suggest that dietary polyphenols can beneficially modulate some of the pathophysiological features associated with metabolic syndrome [9,10]. For example, preclinical evidence demonstrated that dietary supplementation with resveratrol is effective in reducing weight gain, improving insulin sensitivity and reducing hepatic fat deposition in experimental models of high-fat diet induced metabolic syndrome (DIM) [11,12]. In addition to resveratrol, a select, highly tolerable grape seed polyphenolic extract (GSE) has been demonstrated to modulate blood pressure in subjects with metabolic syndrome [13]. We recently demonstrated that select bioactive components from this GSE preparation are capable of penetrating into brain and the concentrations of these polyphenolic components found accumulated in the brain are capable of directly promote synaptic plasticity mechanisms in the brain that are important for memory consolidation [14]. Concord grape juice is yet another dietary polyphenolic rich food with the potential to benefit cognitive function as recent evidence demonstrated that Concord grape juice supplementation improved memory functions in individuals with mild cognitive impairment [15].

In this study, we tested the effect of a combinatorial polyphenol preparation comprised of supplemental resveratrol, GSE and a Concord grape juice extract, defined as Standardized Grape Polyphenol Preparation (SGP), to exert significantly heterogeneous and partially redundant capacities to modulate peripheral and brain pathological features induced by metabolic syndrome. These studies provide a basis for development of safe and effective means to simultaneously mitigate metabolic syndrome-mediated complications in the brain and the periphery. The study suggests that attenuation of features of metabolic syndrome promote brain plasticity mechanisms associated with cognitive function.

2 Materials and Methods

Chemicals and materials

Food grade resveratrol was purchased from ChromaDex (Irvine, CA). GSE was purchased from supplement Warehouse (UPC: 603573579173). Only one lot of the resveratrol and one lot of the GSE were used for this particular study. Both resveratrol and GSE have been shown to be very stable when stored at 4 °C in dark. Welch Concord purple grape juice was purchased at a local market and concentrated by solid phase extraction as described previously [16] to produce a Concord Grape Juice total polyphenol extract. Specifically, Concord juice total polyphenol extract was prepared using C18 solid phase extraction cartridges (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). Juice was diluted 1:4 in acidified water (water buffered to pH 2.4 with o-phosphoric acid) to optimize preservation of the polyphenols in the juice. Diluted juice was loaded onto C18 cartridges followed by washing the columns with 3-volumns of acidified water. Bound organic compounds were eluted in 12% methanol diluted in acidified water. Polyphenol components recovered were concentrated by vacuum centrifugation, which also removed volatile organic components used in the extraction.

Two batches of juice extract were used in the study and the polyphenol profile of this juice extract was confirmed by LC-MS analysis and previously reported [17]. Total polyphenol content was determined to be 62 mg of gallic acid equivalents per mL extract with principle components including anthocynains, proanthocyanidin oligomers, phenolic acids and quercetin glycosides (Table 1).The juice extract was stored in −20 °C in dark and was diluted to the desired concentration once every three days. For all the studies performed, all the polyphenol enriched preparations were subjected for QC test using well validated LC/UV/MS methods to make sure the consistency of chemical profile and total polyphenols. (+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide and quercetin standards were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Malvidin-3-glucoside chloride and cyanidin-3-glucoside chloride were purchased from ChromaDex (Irvine, CA). All extraction and LC solvents were HPLC certified and were obtained from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ).

Table 1. Profile of major polyphenols in extract produced from commercial concord grape juice.

| Anthocyanin | Concentration μmole/L |

Phenolic Acids | Concentration μmole/L |

Flavonoid | Concentration μmole/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dp-Glu | 4677.05 | Gallic acid | 240.71 | Quer-3-Glu | 234.06 |

| Cy-Glu | 3857.81 | Cafteric acid | ND | Quer-3-Glucur | 348.21 |

| Mv-Glu | 592.5 | Vanillic Acid | 0.97 | P1(C) | 3148.84 |

| Pt-Glu | 568 | Caffeic Acid | 320.71 | P1 (EC) | 844.45 |

| Mv-Glu | 642.95 | p-Coumaric Acid | 80.17 | P2 (B1) | 7745.09 |

| Dp-Ac-Glu | 294.52 | 4-HBA | 854.12 | P2 (B2) | 1238.31 |

| Cy-Ac-Glu | 272.45 | ||||

| Pt-Ac-Glu | 285.53 | ||||

| Mv-Ac-Glu | 479.05 | ||||

| Dp-Coum-Glu | 279.75 | ||||

| Total (μM) | 12,287.30 | 1,496.67 | 13,558.96 | ||

| Total (μg/mL) | 5,840.57 | 239.85 | 6,625.51 |

Abbreviations: cy, Cyanidin; dp, Delphinidin; pn, Peonidin; pt, Petunidin; mv, malvidin; glu, glucoside; glucur, glucuronide, Ac-glu, acetylglucoside; Co-glu, coumaroylglucoside; quer, Quercetin, C. catehcin; EC, epicatechin; B1, procyanidin B1; B2, Procyanidin B2. HBA, hydroxybenzoic acid.

SGP Pharmacokinetics

Animal studies were conducted under the guidance and with protocols approved by the Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee (LA12-00014). Bioavailability of phenolics from SGP including metabolites of anthocyanidin-glucosides, monomeric proanthocyanidins (PACs; epicatechin and catechin), quercetin and resveratrol were assessed using a male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rat model. Sixteen SD rats weighed between 275 and 300g were purchased from Harlan Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Rats were randomly assigned to four groups: CTRL, CTRL-SGP, HF, HF-SGP. HF diet (D12492) containing 60% kcal% fat and CTRL diet (D06041501P) containing 10% kcal% fats were purchased from Research Diets Inc. (New Brunswick, NJ). Rats were on the CTRL or HF diets for two weeks prior to SGP treatment and maintained on individual diet throughout the study. Rats were given deionized water ad libitum. SGP were delivered daily by intragastric gavage using plastic feeding tubes (Instech FTP-15-78, Plymoth Meeting, PA) for ten days. To reach proper dosage, rats were gavaged twice a day with 8h apart. Each dose was placed in 1.3 ml water right before gavaging. For non-SGP control, both the CTRL and the HF groups were gavaged with water (vehicle).

Two days prior to pharmacokinetic studies, rats were anesthetized by a dose 3-5% of isoflurane in the anesthesia chamber and maintained with a mask with 1.5-3% isoflurane. A polyethylene catheter was implanted into the jugular vein. Rats were injected with Buprenex (0.01-0.05mg/kg) before regaining consciousness to alleviate pain and allowed to rest for 24 h after surgery. Catheters were kept patent by flushing with heparinized saline (100 units/mL) every 12h. Prior to initiation of pharmacokinetic studies, rats were fasted for 8 h. Pharmacokinetic assessment was conducted on the 10th day of gavage by collecting 400 μL of blood at baseline (prior gavage), 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 h post gavage from the jugular catheter into heparinized tubes. Food was offered at 2h following initiation of pharmacokinetic studies. Fresh blood was processed to plasma by centrifugation at 5500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, acidified with saline (1% ascorbic acid wt/v) in 4:1 ratio, purged with N2 and stored at −80 °C until analysis. The day after pharmacokinetics, another dose was administered and rats were sacrificed 1h post dose. Rats were perfused with ice-cold saline to remove possible blood contamination in tissues prior to harvest. Brain tissues were then harvested and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Solid phase extraction (SPE) for polyphenols

Monomeric PACs, quercetin and resveratrol metabolites were extracted from plasma (~100 μL) by SPE using 1 cc Waters Oasis HLB cartridges (Milford, MA). Acidified plasma samples were thawed and brought up to 0.5 mL with acidified saline (0.1% formic acid v/v). SPE cartridges were preconditioned with 1 mL of ddH2O followed by 1 mL of methanol. After cartridge precondition, samples were loaded onto the cartridges and 1 mL of 1.5M formic acid (v/v) was passed through the column followed by 1 mL of 5% methanol (v/v). Polyphenolic metabolites in plasma were eluted with 2 mL of methanol and dried under vacuum at 37 °C. Dried phenolic extracts were reconstituted with 0.1% aqueous formic acid (v/v) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v) in 4:1 ratio. Reconstituted samples were sonicated for 10s and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

Brain tissues were finely diced into pieces and homogenized with ice-cold methanol (9 mL/g tissue) until a homogenate was obtained. Brain homogenates were centrifuged at 3700 rpm at 4°C for 10 mins and top layer methanol was collected. The methanol extraction process was repeated again with 6 mL of methanol/g tissue. Methanol was dried at 37 °C under vacuum. Dried residues were reconstituted with 1 mL 0.1% aqueous formic acid (v/v) and underwent the same SPE procedure as plasma described above.

Anthocyanins were extracted under the same extraction procedure except for the use of different solvents. SPE cartridges were preconditioned with 3 mL of ddH2O followed by 3 mL of methanol and samples were loaded onto the cartridges. 3 mL of 2% aqueous formic acid (v/v) was used to wash the cartridges. Anthocyanins were eluted with 2 mL of 2% formic acid in methanol (v/v) and dried under vacuum at 37°C. Dried extracts were resolubilized in 100 μL of 2% aqueous formic acid (v/v) for LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Analysis of monomeric PACs and resveratrol from plasma was performed on an Agilent 1100 time of flight (TOF) system. Analysis of all brain polyphenol metabolites and plasma quercetin metabolites and AC derivatives was performed on an Agilent 6400 Triple Quad under multiple reaction monitoring modes (MRM). Both systems were equipped with an ESI source. A Waters XTerra RP-C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 3.5 μm particle size) was used on all analysis. A binary mobile phase system consisted of mobile phase A: 0.1% aqueous formic acid (v/v) and B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v) was used for analysis of monomeric PACs, resveratrol and quercetin metabolites. The column was heated to 30 °C and the system flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. Gradient conditions were: 10% B at 0 min, 40% B at 5.5 min, 70% B at 7 min, 95% B at 7.5 min and back to 10% B at 8.5 min to 13.5 min. Mass spectra was obtained under negative polarity scanning between 100 m/z-1000 m/z on MS-TOF. MRM mass transitions were 479 -< 303 for MeO-EC glucuronides, 465 -< 289 for EC-glucuronides, 289 -< 137 for EC, 403 -< 227 for resveratrol-glucuronide and 227 -< 143 for resveratrol under negative polarity on Triple Quad. MRM mass transitions were 493 -< 317 for MeO-quercetin glucuronide, 479 -< 303 for quercetin glucuronide and 301 -< 153 for quercetin aglycone under positive polarity. Fragmentor voltage was set at 135V and collision energy was 30 eV for quercetin aglycon and 17eV for all other mass transitions. ESI source condition was described as followed: gas temp was 350 °C, drying gas flow was 11 l/min, nebulizer was 30 psi, sheath gas temp was 350°C, sheath gas flow was 11 l/min, capillary voltage was 3500V and nozzle voltage was 1000V. Quantification of monomeric PAC metabolites and resveratrol were estimated by using calibration curves from parent C, EC and resveratrol, respectively. Quantification of quercetin metabolites was accomplished by using a calibration curve constructed with quercetin-3-O-glucuronide standard.

For anthocyanin analysis, the binary mobile phases were A: 2% aqueous formic acid (v/v) and B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v). The gradient used to elute anthocyanins was: 5% B at 0 min, 10% B at 10 min, 25% B at 30 min, 5% B at 31 min and continue on 5% B to 35 min. Mass spectra was obtained under positive polarity. ESI source condition setting was the same as described above. MRM transitions were: 493 -< 331 for malvidin-3-O-glucoside, 479 -<317 for petunidin-3-O-glucoside, 465 -< 303 for delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, 463 -< 301 for peonidin-3-O-glucoside and 449 -< 287 for cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. Quantification of all anthocyanin glucosides except for cyanidin-3-O-glucoside were estimated by using calibration curves of malvidin-3-O-glucoside. Quantification of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside was achieved by a calibration curve constructed with cyanidin-3-O glucoside standard.

Animal model and treatment

Female C57BL6/J mice were purchased from Jackson’s laboratory and housed in the centralized animal care facility of the Center for Comparative Medicine and Surgery (CCMS) at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. The C57BL/6J mouse was used as a model of human metabolic syndrome because it develops a syndrome of obesity, hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia and hypertension when fed a high fat (DIM) diet [18]. Mice were randomly grouped into three groups and received following treatment starting at approximately 3 months of age: Control mice were treated with regular diet (CTRL group, 10 kcal% fat, Research Diets D12450B), Diet-induced metabolic syndrome (DIM) mice were treated with a high fat diet (DIM group, 60 kcal% fat, Research Diets, D12492), DIM mice treated with SGP (DIM-SGP group) received the high fat diet supplemented with 0.4% resveratrol and 0.2% of GSE. CTRL and DIM mice had access to regular water while DIM-SGP mice drank diluted Concord grape juice extract. The juice extract was stored in −20 °C in dark and was diluted to the desired concentration once every three days. The calculated daily intake of GSE is 200mg/kg body weight (BW) [19,20], resveratrol is 400mg/kg BW [12,21] and the total polyphenols from juice extract is 183mg/kg BW [22]. These doses were chosen based on the equivalent doses used in the studies that showed efficacy either in human or animal models for each component [12,19-22]. All animals were maintained on a 12:12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 h in a temperature-controlled (20 ± 2 °C) vivarium and all procedures were approved by the MSSM ICAUC, protocol number LA12-00014.

Intra-peritoneal glucose tolerance test (IGTT)

IGTT was performed as previously reported[23,24] following 6 months treatment. Specifically, mice were given a single dose of intraperitoneal glucose administration (2 g/kg BW) postprandially, and blood was collected from the tail vein periodically over a 3 h period. Blood glucose content was assessed using the Contour blood glucose System (Bayer, IN).

Plasma biochemical indexes

Blood was collected using a heparinized capillary tube and plasma was collected following centrifugation at 1000×g for 15 minutes. Samples were tested using the following commercially available kits: Cholesterol quantitative kit from Biovision (CA); Triglyceride and insulin, leptin, resistin, PAI-1 MCP-1, TNFα and IL-6 were measured using the mouse serum adipokine multiplex MAP kit from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Blood pressure measurement

Blood pressure and heart rate were recorded using a non-invasive commercial blood pressure analysis system designed specifically for small rodents (Hatteras Instruments, NC) as previously described [24,25]. Briefly, mice were temporarily immobilized in a restraining chamber and the tail is inserted through the tail cuff and laid down into the tail slot, secured with a piece of tape. Every mouse underwent 5 preliminary cycles for acclamation and the following 10 measurements of systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were recorded.

Imaging

All imaging was performed on a Bruker Biospec 70/30 system which is a 7T micro MRI scanner. Prior to scanning, mice were anesthetized with 2% Isofluorane in NO2 (75%) and O2 (23%). They were then positioned onto the scanner bed. Anesthesia was maintained at 1.5% isofluorane throughout the scan time. We used a 4 channel mouse brain phased array coil for data acquisition. The protocol was as follow: after a localizer we manually shim the brain region for optimal signal and signal distortion. We acquired resting state fMRI using an EPI BOLD sequence with the following protocol: Segmented EPI (4×), TR=1500ms, TE=18.9ms, Matrix=96×96, FOV=12.8mm, slice thickness=1.1mm, 11 slices. Total acquisition time was around 5 mins per scan, 3 scans were acquired for each mouse. Resting State Analysis: Preprocessing of the functional images began by excluding scans where there was movement. Then, manual brain extraction was performed on the mean functional image. A study specific template was then created based on all the mean functional images using FSL. Independent component analysis (ICA) was used to identify unique networks of resting state activity using MELODIC[26] as implemented in FSL. Several resting networks were identified for each subject and z-statistic images were extracted and entered higher-level analyses. General linear modeling and permutation-based inference testing (RANDOMISE) were used to test for group differences and symptom severity correlates of the default mode network. Dual regression was used to test for differences in resting state coactivation between groups [27,28].

Electrophysiological Recordings

Mice were sacrificed by decapitation and the brains were quickly removed. Hippocampal slices (350 μm) were made and placed into oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at 29 °C for a minimum of 90 min to acclimatize. Slices were then transferred to a recording chamber (Fine Science Tools Inc, CA, USA) and perfused continuously with oxygenated-ACSF at 32 °C. For extracellular recordings: CA1 field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded by placing stimulating and recording electrodes in CA1 stratum radiatum. Basal synaptic transmission was assayed either by plotting the stimulus voltages against slopes of fEPSP, or by plotting the peak amplitude of the fiber volley against the slope of the fEPSP. For long term potentiation (LTP) experiments, a 15 min baseline was recorded every min at an intensity that evokes a response ~35% of the maximum evoked response. LTP was induced using θ-burst stimulation (4 pulses at 100 Hz, with the bursts repeated at 5 Hz and each tetanus including three 10-burst trains separated by 15 s) and fEPSPs were monitored for 60 min to assess the magnitude of potentiation.

Statistical analysis

For bioavailability studies, differences between means were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. For plasma biochemical analysis, differences between means were analyzed using two-tailed Student t-test. For electrophysiology study, body weight and glucose tolerant test, data were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis. In all analyses, the null hypothesis was rejected at the 0.05 level. All statistical analyses were performed using the prism Stat program (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

3 Results

The effect of diets on the pharmacokinetics and brain bioavailability of SGP

Several factors including food/diet composition are known to impact polyphenol bioavailability and metabolism. Establishing what differences may exist in polyphenol absorption and metabolism as a result of dietary composition is critical to development of targeted prevention and treatment regimes modulating metabolic syndrome. In this study, we tested whether dietary condition, especially the amount of fat in the diet which is a major concern for the Western diet, could interfere with plasma pharmacokinetic response and brain absorption and accumulation.

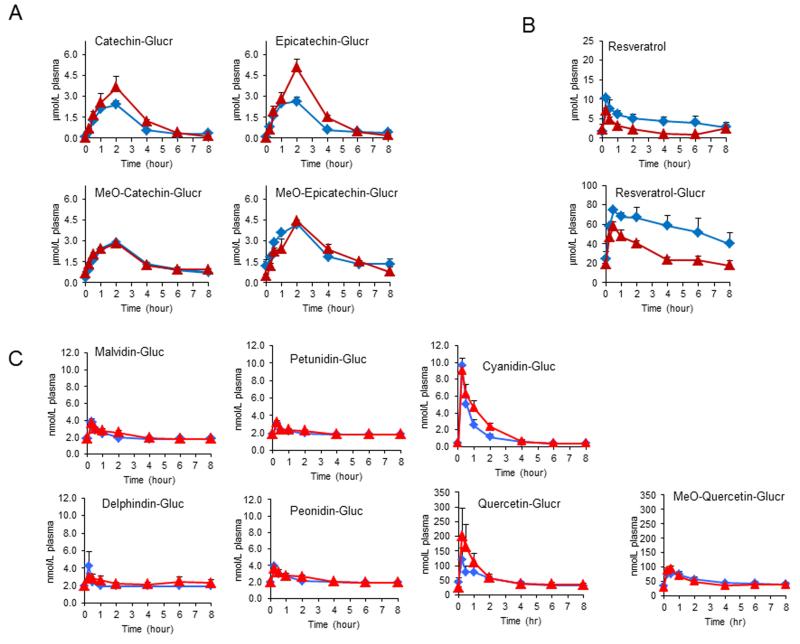

We first measured the plasma pharmacokinetic response to SGP treatment following two weeks high fat or control diet regime. We found similar pharmacokinetic profiles for GSE metabolites following either low fat or high fat diet treatment. Specifically, the primary circulating forms of catechin (C) and epicatechin (EC): 3′-O-methyl-(±)-C-O-β-glucuronide (3′-MeO-C-Glucr), 3′-O-methyl-EC-O-β-glucuronide (3′-MeO-EC-Glucr), (±)-C-O-β-glucuronide (C-Glucr) and (−)-EC-O-β-glucuronide (EC-Glucr) can be detected 15 minutes after the oral administration, peaked at 2 hours and subsides almost to baseline at 8 hours (Fig. 1A). There seemed to be a higher peak level of glucuronidated C and EC in the plasma following a high fat diet regime compared to the control diet with EC-Glucr significantly higher in animals on high fat diet. The levels of resveratrol and resveratrol glucuronide were significantly higher in the plasma following high fat diet compared to those from low fat rats (Fig. 1B), indicating co-consumed fat might promote acute absorption of resveratrol from the diet. The plasma pharmacokinetic responses to juice polyphenol forms following the two diet treatment were almost identical. The major circulating metabolites from the purple grape juice polyphenol extract were quercetin-glucuronide (Quer-Gluc), methyl-O-quercetin-glucuronide (MeO-Quer-Gluc), cyanidin-glucuronide (Cyn-Gluc), delphinidin-glucuronide (Del-Gluc) and malvidin-glucuronide (Mal-Gluc) (Fig. 1C). No grape derived polyphenols were found in any of the samples of rats in the CTRL or HF groups dosed only with water.

Figure 1. Plasma pharmacokinetic response to SGP following 10 days of intragastric gavage of SGP from rats under different dietary regimes.

(A) catechin glucuronide, epicatechin glucuronide and their corresponding methylated metabolites, (B) resveratrol and resveratrol glucuronide, (C) five major anthocyanin glucosides and quercetin glucuronide and its methylated metabolite. CTRL diet (△) and high fat diet (◇). Data represents mean ± SEM with n=3-4 rats per group.

Collectively, these data suggest that plasma pharmacokinetic responses of major polyphenol metabolites from grape SGP did not seem to be significantly influenced by the background diet. The possible exception to this finding was resveratrol, for which the absorption or/and metabolism seem to be slightly improved under high fat diet regime.

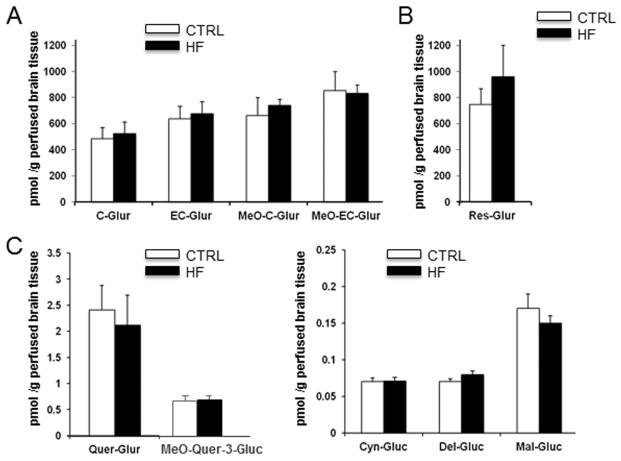

Since metabolic syndrome not only affects peripheral but also influence brain health. A central issue in developing dietary supplements for the central nervous system is whether they can cross the blood brain barrier and whether sufficient concentrations of the bioactive components reach the brain. We then measured the accumulation of individual polyphenol metabolites in perfused brains of Sprague Dawley rats following 10 days of SGP treatment with a background of a control diet (CTRL) or the DIM diet (DIM). We found that all the main metabolites identified in the plasma can be detected in the perfused brain tissue and that specific metabolites can accumulate in brain tissues at nM to μM levels. Further, background diet (DIM versus control) had no significant impact on apparent accumulation of these metabolites by brain tissues (Fig. 2A-2C).

Figure 2. Brain concentration of polyphenol metabolites following 10 days of intragastric gavage of SGP from rats under different dietary regimes.

(A) catechin glucuronide, epicatechin glucuronide and their corresponding methylated metabolites, (B) resveratrol glucuronide, (C) quercetin glucuronide and its methylated glucuronide, (D) cyanidin, delphinidin and malvidin glucoside. Data represents mean ± SEM n=3-4 rats per group.

Periphery benefits of SGP on metabolic syndrome

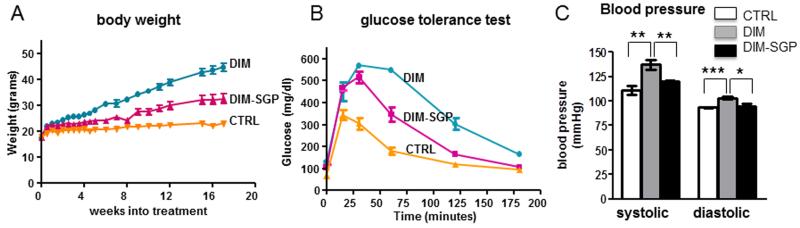

Following the bioavailability study, we treated C57BL/6J mice with the high fat diet or high fat diet supplemented with SGP starting at 2 months of age. Following 6 months treatment, we found that the DIM mice developed sever metabolic syndrome as reflected by the tremendous body weight gain (p<0.0001 DIM vs. CTRL, Fig. 3A), impaired IGTT (p<0.0001 DIM vs. CTRL, Fig. 3B) and increased blood pressure, both systolic and diastolic (Fig. 3C). Supplementation of SGP significantly reduced the body weight gain, improved IGTT and reduced the blood pressure to the level of CTRL mice (Fig. 3A, 3B and 3C).

Figure 3. SGP treatment prevented peripheral metabolic syndrome phenotype.

(A) body weight, (B) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerant test, (C) blood pressure. Data represents mean ± stdev. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, n=7-8 per group.

Moreover, administration of SGP also significantly reduced the level of cholesterol in plasma (Table 2). We did not find any significant changes of the plasma levels of triglyceride, free fatty acid or ketone bodies following high fat diet treatment (Table 2).

Table 2. Plasma biochemistry following treatment.

| CTRL | DIM | DIM-SGP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cholesterol (mg/ml) | 0.85 ± 0.09*** | 1.27 ± 0.16 | 0.93 ± 0.16** |

| triglyceride (mg/ml) | 0.85 ± 0.13 | 0.78 ± 0.27 | 0.62 ± 0.1 |

| insulin (ng/ml) | 1.08 ± 0.4** | 1.95 ± 0.28 | 1.1 ± 0.48** |

| amylin (pM) | 5.3 ± 3.9* | 18.1 ± 9.5 | 4.6 ± 3.8** |

| glucagon (pM) | 16.1 ± 5.4* | 7.3 ± 5.1 | 12.6 ± 10.2 |

| leptin (pg/ml) | 2314 ± 1378** | 14408 ± 6804 | 6094±7210 |

| PAI-1 (pg/ml) | 1756 ± 1892 | 2378 ±1055 | 1722 ± 822 |

| MCP-1 (pg/ml) | 5.48 ± 11.1* | 20.4 ± 11.9 | 1.4 ± 3.1** |

| resistin (pg/ml) | 2378 ± 387** | 3592 ± 785 | 2568 ± 684* |

Plasma values are expressed as Mean±STDEV;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001 vs. DIM; n=6 per group.

Insulin, amylin and glucagon are hormones secreted by pancreatic cells. Insulin and glucagon are largely responsible for controlling plasma levels of glucose. Following high fat diet treatment, the DIM mice showed significant increase in the levels of insulin, and amylin and reduced level of glucagon in circulation while the administration of SGP prevented these alteration and the levels were comparable to those of the control mice (Table 2).

Leptin is a most important hormone secreted mainly by adipocytes and directly reflects the total amount of fat in the body. Circulating plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is mainly secreted by adipose tissue and is associated with risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. We found that SGP treatment could significantly reduce the levels of leptin and PAI-1 induced by high fat diet in the mice (Table 2)

Inflammation is closely associated with metabolic syndrome. It was proposed that chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)/CC-chemokine ligand 2 as a major promoter of inflammation, plays an important role in renal injury and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy (Tesch review 2008). Resistin in rodent is secreted by adipose tissue and highly implicated in inflammation. Measurements of those inflammation markers in plasma samples from the DIM mice revealed that there were elevated levels of resistin and MCP-1 in circulation compare to the CTRL mice following 5 months of diet treatment. The administration of SGP significantly reduced the levels of all these inflammatory cytokines (Table 2).

Benefits of SGP on metabolic syndrome induced brain network abnormality

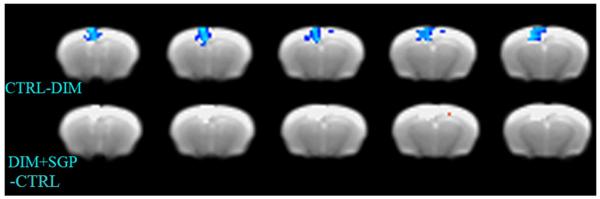

To evaluate the effect of metabolic syndrome on brain network connectivity and the potential benefits of polyphenols, we scanned the mice and analyzed the resting state fMRI data. Using dual regression analysis between the 3 groups of mice, namely CTRL (n=13), DIM (n=11) and DIM-SGP (n=9), we found significant differeces between the CTRL and DIM mice in the Default Mode Network (DMN). Figure 4 illustrates 5 coronal slices that contained the significantly correlated regions of the orbital, prelimbic and cingulate cortices that are part of the DMN. The blue color represents voxels that are significantly different between the DIM mice and the CTRL mice and the DIM mice showed greater functional connectivity activation compared to the CTRL mice (Figure 4, top panel). This result can be explained by an efficiency model of the brain [29,30] that inefficient firing of the neurons causes increased activity in the individual neurons due to lack of feedback signals [31]. There was no difference detected between CTRL and DIM-SGP group (Figure 4, bottom panel), suggesting polyphenol treatment might be able to prevent metabolic syndrome induced abnormality in the brain.

Figure 4. Voxel by voxel statistics of the default mode network superimposed on anatomical MRI.

5 coronal slices that contained the significantly correlated regions of the orbital, prelimbic and cingulate cortices that are part of the default mode network (DMN). Group t-tests were performed on the DMN between the three groups: CTRL, DIM and DIM-SGP. Top panel: rsFMRI analysis CTRL vs. DIM mice, blue represents significant increase of signals in DIM mice compare to CTRL mice; Bottom panel: rsFMRI analysis of CTRL vs. DIM-SGP mice. Image thresholded at p<0.05, n=9-13 per group.

Benefits of SGP on brain synaptic plasticity

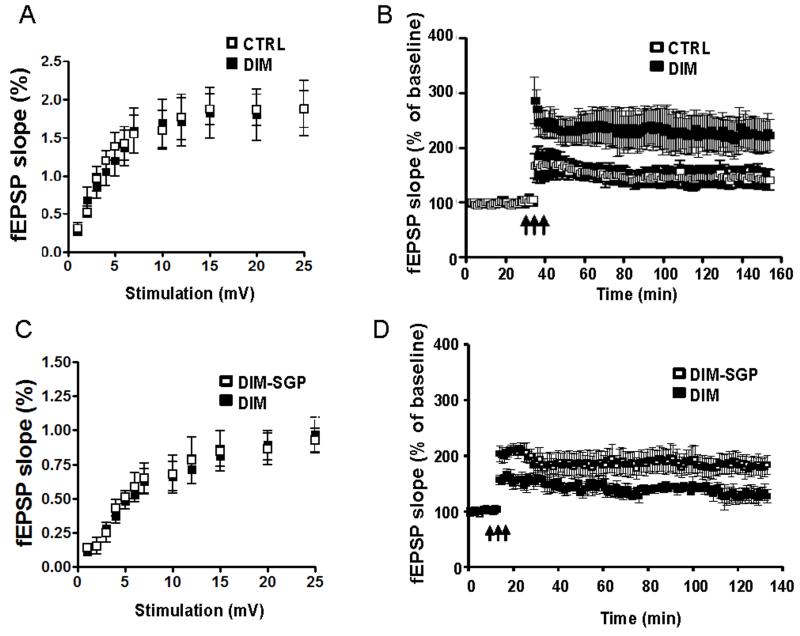

To test whether the brain network abnormality in DIM mice is associated with synaptic impairment, we performed the electrophysiology study to evaluate the basal synaptic transmission and LTP which are important neuronal mechanisms involved in learning and memory. We found there was no difference in the input-output curves generated using the fEPSP versus stimulus intensity between the DIM and CTRL mice (Fig. 5A). We next examined the synaptic plasticity in the CA1 region of hippocampal formation. We found that LTP is significantly impaired in the DIM mice compared to the CTRL mice. In the DIM mice, 60 minutes after the theta burst stimulus, responses were 165 ± 12% while in the CTRL mice, the response were 245±18% (Fig. 5B, p<0.05). Next, we compared the DIM-SGP mice with the DIM mice. We found that chronic SGP treatment can prevent or rescue the synaptic abnormality as reflected by much improved responses following high frequency stimulation: expressed as a percentage of baseline field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) slope compared to the DIM mice (225 ± 15% vs. 165 ± 12%, p < 0.01, Fig. 5D). There was no difference in the input-output curves (Fig. 5C)

Figure 5. SGP treatment prevented DIM-induced synaptic impairments in hippocampal slices.

(A-B) Input-output curve of basal synaptic transmission and LTP in hippocampal slices isolated from CTRL (□) or DIM (■) mice. (C-D) Input-output curve of basal synaptic transmission and LTP in hippocampal slices isolated from DIM (■) or DIM-SGP (□) mice. The fEPSPs were recorded from the CA1 region. The arrow indicates the beginning of tetanus to induce LTP.

4 Discussion

Metabolic syndrome is a multifactorial disease that manifests its pathological features both in the periphery and in the central nervous system. People with metabolic syndrome have an increased risk of developing age-related dementia which can pose a tremendous burden on the healthcare system.

Plant-derived polyphenolic compounds have been identified as disease preventative agents and as promising dietary supplements in prevention and treatment of chronic and degenerative diseases including cancer and cardiovascular disorders, due, in part, to their diverse biological activities including strong anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and anti-tumorogenic activities [32-35]. However, the beneficial effects of polyphenols are dependent on the delivery of biologically active polyphenol metabolites to target tissues. Several factors are known to impact polyphenol bioavailability and metabolism including food matrix, macro and micronutrient composition, and presence of other polyphenol forms [36,37]. Among these factors, the amount of fat in the diet is a major concern for the Western society and it could potentially interfere with absorption and accumulation of bioactive polyphenol metabolites. Pharmacokinetic studies showed that dietary fat content have minimal impact on the intestinal absorption and plasma distribution of individual metabolites derived from GSE or juice polyphenol extract. Moreover, brain bioavailability data also showed that regardless of dietary fat content in the background diet, major metabolites from SGP appear to accumulate in brain tissues at comparable levels. These data suggest that SGP can be applied to people with different dietary habits, especially to people that conventionally take high-fat, high-caloric diet which can potentially lead to metabolic syndrome.

Previously, it was shown that resveratrol could significantly reduce the plasma levels of insulin and fasting glucose in C57BL/6NIA mice fed with similar high fat diet [38]. Other grape derived polyphenols such as grape seed procyanidins and quercetin were also shown to improve fasting plasma insulin, reduce hyperglycemia and reduce blood pressure in various experimental models [39-44]. In this study, we demonstrated that using a combination of polyphenols composed of resveratrol, GSE and Concord grape juice extract not only reduced plasma levels of insulin and improve glucose utilization, but could prevent almost all the peripheral symptoms of metabolic syndrome, including reduced blood pressure, reduced plasma level of cholesterol, reduced inflammation.

Numerous epidemiological studies suggest that people with metabolic syndrome might have increased risk of developing age-related dementia. Increasing body of evidence suggest that the increased risk of dementia is associated with neurophysiological and structural changes in the brain and is believed to be attributable to several pathologic factors including altered neuronal metabolism (hypometabolism), microvascular dysfunction, and eventually reduced neuroplasticity. In animal models, it has also been shown that certain aspects of the metabolic syndrome can induce neurological deficits, including reduced hippocampal dendritic spine density, reduced LTP and impaired learning ability [45-48]. Our rsFMRI imaging study demonstrated that the DIM mice had stronger signal intensities in multiple brain regions compared to the CTRL mice. This is consistent with the theory that a defective brain requires much more energy to accomplish the same task than an efficient brain [29,49]. When a brain network, which may or may not involve feedback, is defective either due to synaptic inefficiency or impaired axonal conduction efficiency, some of the nodes will try to increase signaling in order to achieve their goal. It is also possible that due to compromised white matter, haphazard signaling is contributing to the increase in signaling. A defective brain might also not be signaling coherently either due to mis-wiring or due to defective wiring. Defective interhemispheric fibers might lead to increased signaling by certain regions that are trying to pass information to the contralateral side. Supplementation of SGP prevented these alterations and the signal intensities of different brain regions are comparable to those of the CTRL mice. These data suggests that SGP treatment might be able to prevent DIM induced brain network abnormality (e.g. increased metabolic signaling). This observation is also consistent with the electrophysiology study that the DIM mice elicited a much lower LTP compared to the CTRL mice at the CA1 region and supplementation of SGP almost completely restored the LTP response to the level of the CTRL mice.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that supplementation of SGP can prevent peripheral symptoms as well as central brain abnormalities induced by metabolic syndrome. These parameters include plasma levels of insulin, cholesterol and leptin which are periphery markers reflective of DIM and the central nervous system markers such as LTP and brain connectivity. It is not clear whether the benefits observed in the central nervous system are results of peripheral improvements by SGP in controlling hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia and reducing blood pressure. It is also possible that brain targeting polyphenol metabolites can directly act within the brain to restore synaptic plasticity, for example, 3′-MeO-C-Gluc and MeO-Quer-Gluc have previously been shown to improve LTP in hippocampal slices [14]. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome has steadily increased over the years and poses a serious burden on the US health care system. People with metabolic syndrome are more likely to experience cognitive decline. It is crucial to take preventative and therapeutic measures in these populations. Our studies provided preclinical evidence that grape derived polyphenols comprised of multiple bioavailable and bioactive components that target a wide range of metabolic syndrome-related pathological features can provide greater global protection against both peripheral and central nervous system dysfunctions. Collectively, our studies suggest that attenuation of features of metabolic syndrome promote brain plasticity mechanisms that are important for learning and memory.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by discretionary funding to GMP. No conflict of interest exists for all authors of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- SGP

Standardized Grape Polyphenol Preparation

- DIM

Diet-induced metabolic syndrome

- GSE

Grape seed polyphenolic extract

- PACs

Proanthocyandins

- SD

Sprague-Dawley

- CTRL

Control

- HF

High fat

- SPE

Solid phase extraction

- TOF

Time of flight

- MRM

Multiple reaction monitoring modes

- BW

Body weight

- IGTT

Intra-peritoneal glucose tolerance test

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- ICA

Independent component analysis

- ACSF

Artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- fEPSPs

field excitatory postsynaptic potentials

- LTP

Long term potentiation

- C

Catechin

- EC

Epicatechin

- 3′-MeO-C-Gluc

3′-O-methyl-(±)-C-O-β-glucuronide

- 3′-MeO-EC-Gluc

3′-O-methyl-EC-O-β-glucuronide

- C-Gluc

(±)-C-O-β-glucuronide

- EC-Gluc

(−)-EC-O-β-glucuronide

- Quer-Gluc

quercetin-glucuronide

- MeO-Quer-Gluc

methyl-O-quercetin-glucurinide

- Cyn-Gluc

cyanidin-glucuronide

- Del-Gluc

delphinidin-glucuronide

- Mal-Gluc

malvidin-glucuronide

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- cy

Cyanidin

- dp

Delphinidin

- pn

Peonidin

- pt

Petunidin

- mv

Malvidin

- glu

Glucoside

- Glucur

glucuronide

- Acu-glu

Acetylglucoside

- Co-glu

coumaroylglucoside

- Quer

Quercetin

- B1

procyanidin B1

- B2

procyanidin B2

- HBA

hydroxbenzoic acid

Reference List

- [1].Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003-2006. National Health Statistic Report. 2009;13:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].van den BE, Biessels GJ, de Craen AJ, et al. The metabolic syndrome is associated with decelerated cognitive decline in the oldest old. Neurology. 2007;69:979–85. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271381.30143.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Muller M, Tang MX, Schupf N, et al. Metabolic syndrome and dementia risk in a multiethnic elderly cohort. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:185–92. doi: 10.1159/000105927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Razay G, Vreugdenhil A, Wilcock G. The metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:93–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yaffe K, Haan M, Blackwell T, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline in elderly Latinos: findings from the Sacramento Area Latino Study of Aging study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:758–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Komulainen P, Lakka TA, Kivipelto M, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cognitive function: a population-based follow-up study in elderly women. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23:29–34. doi: 10.1159/000096636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dik MG, Jonker C, Comijs HC, et al. Contribution of metabolic syndrome components to cognition in older individuals. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2655–60. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Profenno LA, Porsteinsson AP, Faraone SV. Meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease risk with obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cherniack EP. Polyphenols: planting the seeds of treatment for the metabolic syndrome. Nutrition. 2011;27:617–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hanhineva K, Torronen R, Bondia-Pons I, et al. Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:1365–402. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Burgess TA, Robich MP, Chu LM, et al. Improving glucose metabolism with resveratrol in a swine model of metabolic syndrome through alteration of signaling pathways in the liver and skeletal muscle. Arch Surg. 2011;146:556–64. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127:1109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sivaprakasapillai B, Edirisinghe I, Randolph J, et al. Effect of grape seed extract on blood pressure in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2009;58:1743–6. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang J, Ferruzzi MG, Ho L, et al. Brain-Targeted Proanthocyanidin Metabolites for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2012;32:5144–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6437-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Krikorian R, Nash TA, Shidler MD, et al. Concord grape juice supplementation improves memory function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:730–4. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ho L, Chen LH, Wang J, et al. Heterogeneity in Red Wine Polyphenolic Contents Differentially Influences Alzheimer’s Disease-type Neuropathology and Cognitive Deterioration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:59–72. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xu Y, Simon JE, Welch C, et al. Survey of polyphenol constituents in grapes and grape-derived products 1. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:10586–93. doi: 10.1021/jf202438d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Surwit RS, Feinglos MN, Rodin J, et al. Differential effects of fat and sucrose on the development of obesity and diabetes in C57BL/6J and A/J mice. Metabolism. 1995;44:645–51. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang J, Ho L, Zhao W, et al. Grape-derived polyphenolics prevent Abeta oligomerization and attenuate cognitive deterioration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6388–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0364-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang J, Santa-Maria I, Ho L, et al. Grape derived polyphenols attenuate tau neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:653–61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Vingtdeux V, Giliberto L, Zhao H, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling activation by resveratrol modulates amyloid-beta peptide metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9100–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Krikorian R, Nash TA, Shidler MD, et al. Concord grape juice supplementation improves memory function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:730–4. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang J, Ho L, Qin W, et al. Caloric restriction attenuates beta-amyloid neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:659–61. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3182fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang J, Ho L, Chen L, et al. Valsartan lowers brain beta-amyloid protein levels and improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3393–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI31547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].az-Ruiz C, Wang J, Ksiezak-Reding H, et al. Role of Hypertension in Aggravating Abeta Neuropathology of AD Type and Tau-Mediated Motor Impairment. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;2009:107286. doi: 10.1155/2009/107286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:137–52. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, et al. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis 1. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1001–13. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zuo XN, Kelly C, Adelstein JS, et al. Reliable intrinsic connectivity networks: test-retest evaluation using ICA and dual regression approach. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2163–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Haier RJ, Siegel BV, Jr., MacLachlan A, et al. Regional glucose metabolic changes after learning a complex visuospatial/motor task: a positron emission tomographic study. Brain Res. 1992;570:134–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90573-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tang CY, Eaves EL, Ng JC, et al. Brain networks for working memory and factors of intelligence assessed in males and females with fMRI and DTI. Intelligence. 2010:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tang CY, Eaves E, Dams-O’Connor K, et al. Diffuse Disconnectivity in TBI: A Resting State fMRI and DTI Study. Translational Neuroscience. 2012:9–14. doi: 10.2478/s13380-012-0003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ishikawa T, Suzukawa M, Ito T, et al. Effect of tea flavonoid supplementation on the susceptibility of low-density lipoprotein to oxidative modification. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:261–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jankun J, Selman SH, Swiercz R, et al. Why drinking green tea could prevent cancer. Nature. 1997;387:561. doi: 10.1038/42381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rahman I, Biswas SK, Kirkham PA. Regulation of inflammation and redox signaling by dietary polyphenols. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1439–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yang CS, Landau JM, Huang MT, et al. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by dietary polyphenolic compounds. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:381–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Neilson AP, Sapper TN, Janle EM, et al. Chocolate matrix factors modulate the pharmacokinetic behavior of cocoa flavan-3-ol phase II metabolites following oral consumption by Sprague-Dawley rats 4. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:6685–91. doi: 10.1021/jf1005353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Del RD, Borges G, Crozier A. Berry flavonoids and phenolics: bioavailability and evidence of protective effects. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(Suppl 3):S67–S90. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].El-Alfy AT, Ahmed AA, Fatani AJ. Protective effect of red grape seeds proanthocyanidins against induction of diabetes by alloxan in rats 4. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pinent M, Blay M, Blade MC, et al. Grape seed-derived procyanidins have an antihyperglycemic effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and insulinomimetic activity in insulin-sensitive cell lines 4. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4985–90. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Montagut G, Blade C, Blay M, et al. Effects of a grapeseed procyanidin extract (GSPE) on insulin resistance 1. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:961–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Al-Awwadi NA, Bornet A, Azay J, et al. Red wine polyphenols alone or in association with ethanol prevent hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and production of reactive oxygen species in the insulin-resistant fructose-fed rat 2. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:5593–7. doi: 10.1021/jf049295g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Al-Awwadi N, Azay J, Poucheret P, et al. Antidiabetic activity of red wine polyphenolic extract, ethanol, or both in streptozotocin-treated rats 1. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:1008–16. doi: 10.1021/jf030417z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Banini AE, Boyd LC, Allen JC, et al. Muscadine grape products intake, diet and blood constituents of non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects 1. Nutrition. 2006;22:1137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gerges NZ, Aleisa AM, Alkadhi KA. Impaired long-term potentiation in obese zucker rats: possible involvement of presynaptic mechanism 6. Neuroscience. 2003;120:535–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Li XL, Aou S, Oomura Y, et al. Impairment of long-term potentiation and spatial memory in leptin receptor-deficient rodents 3. Neuroscience. 2002;113:607–15. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hwang LL, Wang CH, Li TL, et al. Sex differences in high-fat diet-induced obesity, metabolic alterations and learning, and synaptic plasticity deficits in mice 1. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:463–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Stranahan AM, Norman ED, Lee K, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity and cognition in middle-aged rats 1. Hippocampus. 2008;18:1085–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tang CY, Eaves EL, Ng JC, et al. Brain networks for working memory and factors of intelligence assessed in males and females with fMRI and DTI. Intelligence. 2011;38:293–303. [Google Scholar]