Abstract

Objective

This study aims to examine the associations between microfinance programme membership and intimate partner violence (IPV) in different socioeconomic strata of a nationally representative sample of women in Bangladesh.

Methods

The cross-sectional study was based on a nationally representative interview survey of 11 178 ever-married women of reproductive age (15–49 years). A total of 4465 women who answered the IPV-related questions were analysed separately using χ2 tests and Cramer's V as a measure of effect size to identify the differences in proportions of exposure to IPV with regard to microfinance programme membership, and demographic variables and interactions between microfinance programme membership and factors related to non-economic empowerment were considered.

Results

Only 39% of women were members of microfinance programmes. The prevalence of a history of IPV was 48% for moderate physical violence, 16% for severe physical violence and 16% for sexual violence. For women with secondary or higher education, and women at the two wealthiest levels of the wealth index, microfinance programme membership increased the exposure to IPV two and three times, respectively. The least educated and poorest groups showed no change in exposure to IPV associated with microfinance programmes. The educated women who were more equal with their spouses in their family relationships by participating in decision-making increased their exposure to IPV by membership in microfinance programmes.

Conclusions

Microfinance plans are associated with an increased exposure to IPV among educated and empowered women in Bangladesh. Microfinance firms should consider providing information about the associations between microfinance and IPV to the women belonging to the risk groups.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

National representative sample from entire Bangladesh.

Cross-sectional study design implies that the results can only be used to hypothesise about intimate partner violence causes.

Standards on ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence set by the WHO were strictly adhered to, aiming towards ensuring women's safety while maximising the disclosure of the actual violence.

Introduction

A growing body of research has recognised that intimate partner violence (IPV) has far-reaching health and economic impacts for women and societies worldwide.1 IPV, in all forms, occurs every day in all parts of the world, cutting across age, religion, societal, ethnic and geographic borders. However, women who live in poverty have been reported to be particularly exposed to IPV.2–5 The association between domestic violence and gender imbalance is also a known consequence of the subordinate status of women.6 7 In this context, economic empowerment has been highlighted in policy-making to reduce the gender imbalance and to improve the social status of women.8 Microfinance programmes were introduced in the 1990s throughout the developing countries as income-generating projects to provide credit and savings services, particularly to poor women lacking a formal education. The relationships between microfinance programmes and improved status of child mortality, nutrition, immunisation coverage and contraceptive use have been documented.9–12 In addition, descriptive epidemiological studies of the associations between microfinance programmes and IPV have reported promising findings of reduced IPV,13–15 and a recent cluster randomised trial from southern Africa concluded that a combined microfinance and training programme reduced IPV among participants.16 However, studies using qualitative methods17 have identified microfinance as an exacerbating factor for IPV in Bangladesh. The interactions between microfinance programmes, gender issues, education and IPV thus warrant further epidemiological investigations in low-income countries.

Bangladesh is known globally for its microfinance programmes, especially after the acknowledgment from the Nobel Committee.18 This study set out to examine the associations between membership in microfinance programmes and exposure to IPV in different strata of a nationally representative sample of women in Bangladesh. In a previous research, microfinance programmes have been regarded as a general vehicle for the empowerment and emancipation of women.4 Simultaneously, IPV in Bangladesh has been reported as a sociomedical problem closely related to gender inequality and the position of women in the society.5 19 Therefore, we also wanted to study the interactions between empowerment of women through microfinance and non-economic empowerment through spousal equity and formal education.

Methods

The study was based on a cross-sectional design, implemented in Bangladesh through a nationally representative household survey. Reporting of the study was organised according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.20

Data collection

Data collection was conducted by an interview survey in all six administrative divisions of Bangladesh: Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Rajshahi and Sylhet. Details of the survey are available at http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR207/FR207[April-10–2009].pdf. The survey was designed to be representative for most of the demographic indicators for the country as a whole, for each of the six divisions and for the urban and the rural areas separately. Initially, multistage cluster sampling was used, based on the 2001 population census. In total, 361 representative sample clusters were identified, 227 in the rural areas and 134 in the urban areas. From the sample clusters, 10 819 households were identified for the survey initially. Of these households, 10 416 were found to be occupied and 10 400 were available for the survey. All ever-married women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who slept in the selected households the night before the survey were defined as being eligible for the present study. From the survey households, 11 178 eligible women were identified for interview.

A total of 128 experienced field staff, trained for the task, in 12 interview teams conducted the interviews. Each team consisted of one male supervisor, one female field editor, five female interviewers, two male interviewers and one logistics staff member. Four quality control teams ensured data quality; each team included one male and one female data quality control worker. In the presence of the perpetrator, interviewing the victim carries the risk of further violence. Therefore, interviewers received special training on conducting an interview on spousal violence based on a training manual focusing on collecting date on violence in a secure, confidential and ethical manner. Moreover, the IPV questionnaires were administered at the end of the interview, enabling both the interviewer and the respondent to become well acquainted with each other by the time they were discussing the IPV issues.21 The interview teams were also prepared to help the women (respondents) if they asked for assistance, such as helping them to go to the women's shelter, an organisation assisting distressed women. The face-to-face interview took place in a safe and secure place. If the privacy could not be secured for a woman, the interviewers did not ask IPV-related questions.

The survey obtained detailed information on demographics, salient health issues and issues related to domestic violence. The current study utilised variables covering IPV and membership of a microfinance programme. The following variables were used.

Intimate partner violence

The survey data collected on IPV in the recent 12 months (with the latest/current husband) were transformed into the following variables:

Moderate physical violence: had the husband ever pushed, shaken or thrown something; ever slapped; ever punched with a fist or something harmful; ever kicked or dragged.

Severe physical violence: had the husband ever tried to choke or burn; ever threatened with a knife/gun or other weapon; ever attacked with a knife/gun or other weapon.

Sexual violence: had the husband ever physically forced sex when not wanted.

Any violence: having been exposed to at least one of the types of IPV defined above.

All IPV variables measured spousal violence with a shortened and modified Conflict Tactics Scale.22

Microfinance programmes

Microfinance programme membership was coded for respondents who belonged to any of the following organisations: Grameen Bank, BRDB, BRAC, ASHA, PROSHIKA or any microcredit organisation. These are the best known and popular government-approved organisations providing microfinance credit.

Spousal equity

Household decision-making was used as a proxy measure for gender equity in family relations. Specifically, spousal equity was measured through two variables:

Household decision-making on own health issues: respondent alone; jointly by respondent and her husband; respondent and other family members; respondent's husband; someone else in the family.

Household decision-making in household purchase issues: respondent alone; jointly by respondent and her husband; respondent and other family members; respondent's husband; someone else in the family.

The sociodemographic variables used in the present study were respondent age (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44 and 45–49 years), rural–urban residency, education (no education, primary school, secondary school and higher education), religion (Muslim and non-Muslim) and whether the household head was male or female. The economic status was estimated using the wealth index. This index, which divides populations into five economic quartiles (poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest), is widely used for measuring the economic status in developing countries.23

Statistical analysis

χ2 Tests were used to examine the differences in proportions of exposure to IPV (moderate physical, severe physical, sexual and any violence) and association between microfinance and demographic variables (age, residence, education, religion and wealth index) with Cramer's V as a measure of effect size. ORs were calculated to indicate the increase in exposure to IPV associated with membership in microfinance programmes compared with non-membership. For the analysis of interaction effects between spousal equity and microfinance programmes in relation to the sociodemographic variables found associated with IPV, the categories used for the household decision-making variables were recoded to woman deciding (decision was made by the respondent alone, jointly by the respondent and her husband or by the respondent and other family members) and others deciding (decision was made by the respondent's husband or by someone else in the family). IBM SPSS Statistics V.20 was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from the participants before the start of the survey; the right to withdraw and the guarantee of privacy was emphasised to the respondents throughout the survey. The field workers received specific training and support to deal with issues such as domestic violence. The standards on ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence, which are set by the WHO, were strictly adhered to. The WHO recommendations aim towards ensuring women's safety while maximising the disclosure of the actual violence.24

Results

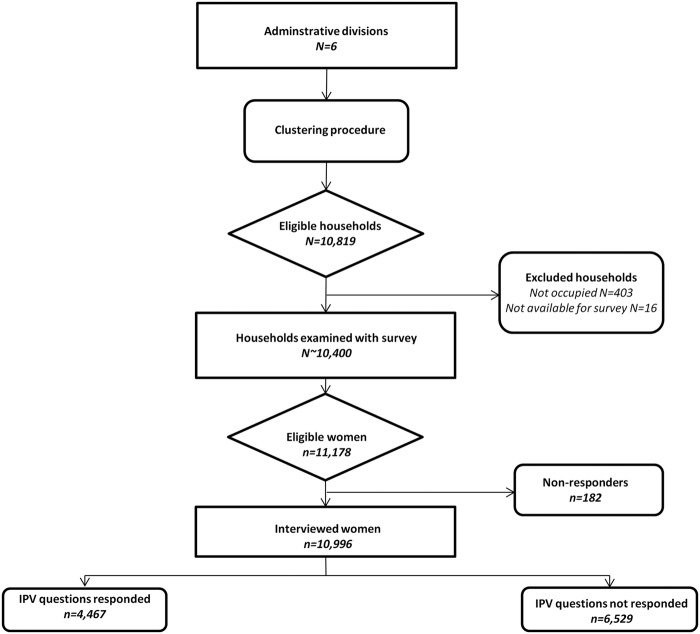

Among 11 178 eligible women, 10 996 (98.4%) were interviewed; 4465 (41%) of the primary survey participants responded to the IPV-related questions (figure 1). The respondents to these questions were more frequently the members of microfinance programmes (39%) than the non-respondents (35%; table 1). It was also found that, among those who responded to the IPV questions, microfinance programme membership was slightly more common among the rural women and women from the households with a male head than the non-responders.

Figure 1.

Study participation displayed according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement (IPV, intimate partner violence).

Table 1.

Prevalence of membership in microfinance programmes among the survey participants divided by response and non-response to the IPV question and displayed by age, residence, education, religion, sex of household head and household wealth index

| Respondents to IPV questions |

Non-respondents to IPV questions |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| Age | ||||||

| 15–19 | 462 | 29 | 886 | 23 | 1348 | 26 |

| 20–24 | 850 | 36 | 1323 | 31 | 2174 | 33 |

| 25–29 | 866 | 43 | 1068 | 37 | 1935 | 40 |

| 30–34 | 742 | 40 | 918 | 39 | 1661 | 39 |

| 35–39 | 701 | 41 | 895 | 41 | 1596 | 41 |

| 40–44 | 462 | 42 | 756 | 38 | 1218 | 40 |

| 45–49 | 380 | 36 | 684 | 35 | 1064 | 35 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 1688 | 36 | 2482 | 33 | 4151 | 34 |

| Rural | 2795 | 40* | 4048 | 36 | 6845 | 37 |

| Education | ||||||

| No education | 1494 | 45 | 2030 | 40 | 3525 | 41 |

| Primary | 1348 | 44 | 1920 | 40 | 3268 | 42 |

| Secondary | 1292 | 31 | 2051 | 29 | 3345 | 30 |

| Higher | 327 | 19 | 528 | 19 | 855 | 19 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Muslim | 4033 | 38 | 5889 | 34 | 9924 | 36 |

| Non-Muslim | 430 | 48 | 641 | 41 | 1072 | 44 |

| Household head | ||||||

| Female | 505 | 25 | 802 | 26 | 1308 | 25 |

| Male | 3958 | 40* | 5728 | 36 | 9688 | 37 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 804 | 47 | 971 | 41 | 1175 | 43 |

| Poorer | 856 | 45 | 1138 | 42 | 1995 | 43 |

| Middle | 849 | 42 | 1246 | 40 | 2095 | 41 |

| Richer | 855 | 41 | 1345 | 37 | 2201 | 38 |

| Richest | 1099 | 23 | 1830 | 22 | 2930 | 22 |

| Total | 4465 | 39* | 6531 | 35 | 10 993 | 36 |

χ2 Tests test for differences in distribution of microfinance programme membership between the respondents and the non-respondents to IPV questions.

Significance for χ2 test is denoted by * (p<0.05, Bonferroni corrected for 22 comparisons in each column).

IPV, intimate partner violence.

Fifty-one per cent (n = 2275 of 4465) of the women who responded to the IPV questions had been the victims of some form of domestic violence (table 2). The specific exposures reported were 48% for moderate physical violence, 16% for severe physical violence and 11% for sexual violence. Forty-nine per cent of the women had not been exposed to any IPV. Having no formal education and belonging to the poorest group, according to the wealth index, were the sociodemographic risk factors most strongly associated with exposure to IPV. Rural residents had a slightly increased proportional rate of exposure to physical and sexual violence, and Muslim women were more exposed to IPV than their non-Muslim peers.

Table 2.

Prevalence of intimate partner violence in the final study population (n=4467) displayed by age, residence, education, religion, sex of household head and household wealth index

| N | Moderate physical violence (%) | Severe physical violence (%) | Sexual violence (%) | Any violence (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 15–19 | 462 | 42 | 14 | 14+ | 46 |

| 20–24 | 851 | 47 | 14 | 15+ | 50 |

| 25–29 | 867 | 49 | 17 | 12 | 52 |

| 30–34 | 743 | 51 | 18 | 11 | 55 |

| 35–39 | 701 | 48 | 17 | 9 | 50 |

| 40–44 | 462 | 49 | 19 | 7− | 50 |

| 45–49 | 381 | 50 | 17 | 5− | 51 |

| Residence | p<0.05, V=0.04 | p<0.01, V=0.05 | |||

| Urban | 1669 | 46 | 16 | 9− | 47− |

| Rural | 2798 | 49 | 17 | 12 | 53 |

| Education | p<0.001, V=0.22 | p<0.001, V=0.17 | p<0.001, V=0.21 | ||

| No education | 1496 | 58+ | 23+ | 12 | 60+ |

| Primary | 1349 | 52+ | 18 | 12 | 56+ |

| Secondary | 1293 | 39− | 10− | 9 | 42− |

| Higher | 327 | 20− | 1− | 8 | 25− |

| Religion | p<0.001, V=0.06 | p<0.01, V=0.05 | p<0.001, V=0.07 | ||

| Muslim | 4036 | 49 | 17 | 11 | 52 |

| Non-Muslim | 430 | 38− | 10− | 6− | 40− |

| Household head | |||||

| Female | 506 | 44 | 16 | 11 | 47 |

| Male | 3961 | 48 | 16 | 11 | 52 |

| Wealth index | p<0.001, V=0.18 | p<0.001, V=0.14 | p<0.001, V=0.11 | p<0.001, V=0.19 | |

| Poorest | 804 | 58+ | 22+ | 16+ | 62+ |

| Poorer | 857 | 53+ | 19 | 13 | 57+ |

| Middle | 850 | 53+ | 18 | 11 | 56+ |

| Richer | 856 | 46 | 17 | 10 | 49 |

| Richest | 1099 | 34− | 8− | 6− | 36− |

| Total | 4467 | 48 | 16 | 11 | 51 |

χ2 Tests are presented for differences in distributions related to each of the variables age, residence, education, religion, household head and wealth index.

Significant χ2 tests (p<0.05, Bonferroni corrected for 6 tests per column yielding p<0.0083) including at least one standardised residual >2 (indicated by +) or <−2 (indicated by −) are reported by p values and effect size V (Cramer's V).

For women with secondary or higher education, microfinance programme membership was associated with a twofold or threefold increase in exposure to IPV, respectively (table 3). Similarly, women at the two wealthiest levels of the wealth index showed a twofold increase in exposure to IPV associated with programme membership. The least educated and poorest groups showed no change in IPV exposure associated with microfinance programmes. The sexual violence did not show any statistically significant increase with microfinance activities.

Table 3.

Associations between IPV and membership in MF programmes in different sociodemographic strata

| Moderate physical violence |

V (OR) | Severe physical violence |

V (OR) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MF |

MF |

No MF |

MF |

||||||||

| N | IPV | No IPV | IPV | No IPV | IPV | No IPV | IPV | No IPV | |||

| Age | |||||||||||

| 15–19 | 462 | 123 | 204 | 72 | 63 | 47 | 280 | 17 | 118 | ||

| 20–24 | 850 | 218− | 327+ | 179+ | 126− | 0.18 (2.1) | 58− | 487 | 62+ | 243 | 0.13 (2.1) |

| 25–29 | 866 | 216 | 279 | 205 | 166 | 73 | 422 | 75 | 296 | ||

| 30–34 | 742 | 207 | 238 | 174 | 123 | 68 | 377 | 63 | 234 | ||

| 35–39 | 701 | 173 | 243 | 160+ | 125− | 0.14 (1.8) | 55 | 361 | 62 | 223 | |

| 40–44 | 462 | 114 | 156 | 114+ | 78− | 0.17 (2.0) | 39 | 231 | 47 | 145 | |

| 45–49 | 380 | 114 | 129 | 74 | 63 | 37 | 206 | 27 | 110 | ||

| Residence | |||||||||||

| Urban | 1668 | 418− | 645+ | 344+ | 261− | 0.17 (2.0) | 138− | 925 | 120+ | 485 | 0.09 (1.7) |

| Rural | 2795 | 747− | 931+ | 634+ | 483− | 0.12 (1.6) | 239− | 1439 | 233+ | 884 | 0.09 (1.6) |

| Education | |||||||||||

| No education | 1494 | 463 | 363 | 402 | 266 | 181 | 645 | 166 | 502 | ||

| Primary | 1348 | 356 | 400+ | 348+ | 244− | 0.12 (1.6) | 115 | 641 | 126 | 466 | |

| Secondary | 1292 | 302− | 591+ | 206+ | 193− | 0.17 (2.1) | 70 | 823 | 54 | 345 | |

| Higher | 327 | 44 | 220 | 22 | 41 | 11 | 253 | 7 | 56 | ||

| Religion | |||||||||||

| Muslim | 4033 | 1093− | 1425+ | 885+ | 630− | 0.15 (1.8) | 357− | 2161 | 329+ | 1186− | 0.10 (1.7) |

| Non-Muslim | 430 | 72 | 151 | 93 | 114 | 20 | 203 | 24 | 183 | ||

| Wealth index | |||||||||||

| Poorest | 804 | 249 | 177 | 219 | 159 | 96 | 330 | 84 | 294 | ||

| Poorer | 856 | 234 | 240 | 221 | 161 | 84 | 390 | 77 | 305 | ||

| Middle | 849 | 237 | 251 | 217 | 144 | 77 | 411 | 76 | 285 | ||

| Richer | 855 | 191− | 311+ | 206+ | 147− | 0.20 (2.3) | 60− | 442 | 89+ | 264 | 0.17 (2.5) |

| Richest | 1099 | 254 | 597 | 115+ | 133− | 0.15 (2.0) | 60 | 791 | 27 | 221 | |

| Sexual violence |

V (OR) | Any violence |

V (OR) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MF |

MF |

No MF |

MF |

||||||||

| N | IPV | No IPV | IPV | No IPV | IPV | No IPV | IPV | No IPV | |||

| Age | |||||||||||

| 15–19 | 462 | 52 | 275 | 15 | 120 | 139 | 188 | 75 | 60 | ||

| 20–24 | 850 | 83 | 462 | 42 | 263 | 245 | 300 | 184+ | 121− | 0.15 (1.9) | |

| 25–29 | 866 | 47 | 448 | 54 | 317 | 231 | 264 | 221+ | 150− | 0.13 (1.7) | |

| 30–34 | 742 | 42 | 403 | 34 | 263 | 223 | 222 | 181 | 116 | ||

| 35–39 | 701 | 29 | 387 | 35 | 250 | 183 | 233 | 164 | 121 | ||

| 40–44 | 462 | 19 | 251 | 12 | 180 | 117 | 153 | 116 | 76− | 0.17 (2.0) | |

| 45–49 | 380 | 14 | 229 | 5 | 132 | 120 | 123 | 75 | 62 | ||

| Residence | |||||||||||

| Urban | 1668 | 90 | 973 | 64 | 541 | 436− | 627+ | 354+ | 251− | 0.17 (2.0) | |

| Rural | 2795 | 196 | 1482 | 133 | 984 | 822− | 856+ | 662+ | 455− | 0.10 (1.5) | |

| Education | |||||||||||

| No education | 1494 | 101 | 725 | 76 | 592 | 486 | 340 | 415 | 253 | ||

| Primary | 1348 | 96 | 660 | 67 | 525 | 389 | 367 | 359 | 233 | ||

| Secondary | 1292 | 74 | 819 | 43 | 356 | 330− | 563+ | 215+ | 184− | 0.16 (2.0) | |

| Higher | 327 | 15 | 249 | 11 | 52 | 53 | 211 | 27+ | 36 | 0.21 (3.0) | |

| Religion | |||||||||||

| Muslim | 4033 | 276 | 2242 | 183 | 1332 | 1183− | 1335+ | 919+ | 596− | 0.13 (1.7) | |

| Non-Muslim | 430 | 10 | 213 | 14 | 193 | 75 | 148 | 97 | 110 | ||

| Wealth index | |||||||||||

| Poorest | 804 | 79 | 347 | 52 | 326 | 271 | 155 | 229 | 149 | ||

| Poorer | 856 | 62 | 412 | 46 | 336 | 255 | 219 | 230 | 152 | ||

| Middle | 849 | 48 | 440 | 44 | 317 | 254 | 234 | 224 | 137 | ||

| Richer | 855 | 45 | 457 | 40 | 313 | 203− | 299+ | 213+ | 140− | 0.20 (2.2) | |

| Richest | 1099 | 52 | 799 | 15 | 233 | 275 | 576 | 120+ | 128− | 0.14 (2.0) | |

Significant χ2 tests for exposure to IPV and belonging to MF programmes are reported by their effect sizes Cramer's V. ORs indicate an increased risk of IPV for women belonging to MF programmes compared with women who did not belong to such programmes. Only significant tests (p<0.05, Bonferroni corrected for 80 tests yielding p<0.000625) including at least one standardised residual >2 (indicated by +) or <−2 (indicated by −) are reported.

IPV, intimate partner violence; MF, microfinance.

The detailed analyses of interaction effects showed that only formally educated women, who were more equal with their spouses in their family relationships, experienced more IPV by membership in microfinance programmes (table 4). Women participating in decision-making about management of their own health issues and who had a higher formal education than primary school were between two and three times more exposed to spousal violence when they were members of microfinance programmes. Among these women, those with the highest formal education were at more than four times higher risk of sexual violence when associated with microfinance than when not. No increase in IPV risk was observed for women who were not involved in decision-making about management of their own health issues. In addition, using decision-making on household purchases as a proxy for spousal equity, the women with formal education experienced an increased spousal violence when they were also the members of microfinance programmes. No such increase in IPV risk associated with microfinance was observed for women who were not involved in decision-making on household purchases.

Table 4.

Increase in risk of intimate partner violence (IPV) by membership in microfinance programmes compared with non-membership displayed with regard to interaction with the woman's educational level and spousal equity (N=4467)

| IPV risk increase associated with microfinance programme membership |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate physical violence | Severe physical violence | Sexual violence | Any violence | |||

| Spousal equity | Woman's education | N | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Health decisions | ||||||

| Woman | No schooling | 956 | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.56) | 1.07 (0.79 to 1.44) | 0.88 (0.58 to 1.32) | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.56) |

| Primary | 865 | 1.83 (1.39 to 2.40) | 1.65 (1.17 to 2.33) | 0.93 (0.61 to 1.40) | 1.83 (1.40 to 2.41) | |

| Secondary | 834 | 2.74 (2.03 to 3.69) | 2.06 (1.31 to 3.24) | 1.34 (0.83 to 2.14) | 2.67 (1.98 to 3.61) | |

| Higher | 255 | 3.20 (1.62 to 6.34) | 2.00 (0.65 to 6.12) | 4.55 (1.85 to 11.19) | 3.20 (1.62 to 6.34) | |

| Other | No schooling | 538 | 1.14 (0.81 to 1.61) | 1.42 (0.94 to 2.14) | 1.00 (0.60 to 1.65) | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.59) |

| Primary | 483 | 1.26 (0.88 to 1.81) | 1.25 (0.77 to 2.03) | 0.79 (0.45 to 1.39) | 1.25 (0.87 to 1.79) | |

| Secondary | 458 | 1.23 (0.81 to 1.86) | 1.41 (0.71 to 2.81) | 1.30 (0.63 to 2.70) | 1.22 (0.80 to 1.84) | |

| Higher | 72 | 1.47 (0.34 to 6.44) | 15.25 (1.24 to 187.85) | – | 1.47 (0.34 to 6.44) | |

| Daily purchase decisions | ||||||

| Women | No schooling | 1034 | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.42) | 1.04 (0.78 to 1.39) | 0.94 (0.62 to 1.41) | 1.10 (0.86 to 1.41) |

| Primary | 882 | 1.92 (1.46 to 2.51) | 1.79 (1.26 to 2.53) | 0.89 (0.57 to 1.37) | 1.90 (1.45 to 2.49) | |

| Secondary | 840 | 2.16 (1.61 to 2.89) | 2.06 (1.32 to 3.23) | 1.34 (0.83 to 2.14) | 2.10 (1.57 to 2.82) | |

| Higher | 249 | 2.90 (1.44 to 5.86) | 2.80 (0.76 to 10.32) | 4.55 (1.61 to 12.81) | 2.90 (1.44 to 5.86) | |

| Other | No schooling | 460 | 1.37 (0.94 to 2.00) | 1.57 (1.01 to 2.42) | 0.95 (0.57 to 1.58) | 1.37 (0.94 to 2.00) |

| Primary | 466 | 1.13 (0.78 to 1.64) | 1.07 (0.66 to 1.75) | 0.91 (0.54 to 1.53) | 1.14 (0.79 to 1.65) | |

| Secondary | 452 | 1.94 (1.26 to 2.98) | 1.28 (0.61 to 2.68) | 1.28 (0.61 to 2.68) | 1.91 (1.24 to 2.94) | |

| Higher | 78 | 2.28 (0.64 to 8.06) | 3.60 (0.74 to 17.48) | 2.49 (0.55 to 11.25) | 2.28 (0.64 to 8.06) | |

Spousal equity is estimated by household decision-making policies regarding health issues and daily household purchases. The risk increase is given as OR with corresponding 95% CIs.

Discussion

Several previous epidemiological studies of IPV,13–15 including an early study from rural Bangladesh,9 have reported a protective effect of microfinance programmes. Our results do not support the assertion that microfinance generally reduces IPV. The results from our study showed a pattern where microfinance was associated with an increased exposure to IPV among women with a formal education. However, educated programme members were less exposed to IPV if they were not involved in the family affairs, that is, no increase in IPV was observed in households where the wife was associated with microfinance but excluded from the day-to-day decision-making. Sexual violence was less clearly associated with different risk of IPV when being part of a microfinance programme. This finding of different patterns between sexual and physical violence hypothesises the existing differences in the causes of sexual and physical IPV, which is in accordance with several previous studies from Bangladesh.5 25–30

There are several limitations that have to be taken into account when interpreting the current results. The study used a cross-sectional design, implying that the results can be used only to hypothesise about the IPV causes. However, the observation that formally educated microfinance programme members who participated in household decision-making were more exposed to IPV suggests that either disagreements between spouses related to the management of household resources were linked to IPV, or that formally educated women who participate in household decision-making are more able to free themselves from an established IPV pattern by participating in microfinance programmes. The current study does not include dowry demands. Therefore, possible effects of dowry demands and/or microfinance plans on IPV are not explored here. Nonetheless, a recent study reports that dowry is uncommon among educated women in Bangladesh.31 Other mechanisms linking microfinance with IPV are more likely to explain these association patterns. Even though the formally educated women were generally less exposed to IPV, microfinance loans may have caused more economic stress in this group due to larger business projects and multiple loans. It is possible that solidarity circles, which extend informal economic reciprocity beyond the family to the local community, were accepted as security for the microfinance loans among the poor. In contrast, formal security limited to the family may have been more common among the more wealthy and educated women. Such circumstances could explain why microfinance in the educated group reported more IPV exposure in interaction with non-financial empowerment, that is, by shared household decision-making.9 Hence, there may have been fewer conflicts in households where the wife was not empowered mainly because the husbands managed the loans in these households single-handedly. In addition, data on when the women joined the microfinance programmes were not collected in the study. Thus, the associations between the microfinance programme membership phase and occurrence of IPV could not be examined. Therefore, further research is needed on the mechanisms by which repayment of microfinance loans is associated with IPV among empowered women in the developing countries.23

Even though the initial survey response rate was 98%, the rate of response to the IPV-related questions was only 39%. However, we found only minor differences in relation to sociodemographic variables between responders and non-responders. Moreover, response bias may have resulted from recall bias or deliberate unwillingness to disclose a history of domestic violence. The participants may have been reluctant to disclose their own victimisation of IPV, given the sensitive nature of the questions and the strong social stigma. Under-reporting of events which are associated with the IPV-related questions may therefore have reduced the primary rates. Nonetheless, we do not expect that such under-reporting influenced the analyses of associations between IPV, microfinance programme membership, spousal equity and the woman's educational level. The analysis included a numerous statistical tests but, with corrections for multiple comparisons, the family-wise error rate was maintained at a reasonable level. The effect sizes were low to moderate. The results are relevant at a group level, but another research design is needed to examine the factors that identify individual women at different risks for IPV.

In accordance with the previous research,3 5 9 about every second woman in our study reported having been a victim of IPV. There is thus ample evidence that women in Bangladesh and other countries in the Indian subcontinent suffer from a heavy burden of IPV, and the identification of predisposing factors as well as countermeasures has recently been called for in this region.25 We found that microfinance programme membership was not associated with a decreased level of IPV in any population strata. The membership was associated with higher IPV exposure among women with a formal education. However, our findings should be interpreted in light of the limitations of the study (ie, a cross-sectional design was used and there was a considerable non-response to the IPV-related survey questions). Other studies in different countries have indicated that the association with microfinance reduces IPV exposure.13–15 The findings in this study raise the question whether the association with microfinance are not always associated with reduced levels of IPV. Therefore additional prospective studies in different settings are warranted to study the mechanisms by which economic stress might be a contributing factor for IPV associated with microfinance, as well as on the effects resulting from interactions between economic and non-economic empowerment.

The results of this study still have policy implications. Microfinance programmes in Bangladesh make claims in their marketing campaigns about social responsibility. These organisations can therefore be expected to act with particular social conscientiousness. According to the results of this study, microfinance firms should be aware that programme membership may increase IPV exposure among women belonging to the risk groups. Alternatively, microfinance firms should be aware that microfinance programme membership among formally educated women might reflect an increased exposure of IPV. However, before the demands to provide information about the risk of IPV can be put on microfinance firms, the identification of the risk groups should be confirmed in prospective studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the field staff and management of measure DHS for procuring data and permission to use them.

Footnotes

Contributors: KD, TT and ÖD conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. ÖD was responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. TT and KD provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by KD and TT and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. KD was responsible for the acquisition of the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the survey was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Opinion Research Corporation (ORC), Macro International Incorporated.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.WHO World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diop-Sidibe N, Campbell J, Becker S. Domestic violence against women in Egypt. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1260–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JC, Watts CH, Hargreaves JR, et al. Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women's empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1794–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalal K, Rahman F, Jansson B. Wife abuse in rural Bangladesh. J Biosoc Sci 2009;41:561–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan ME, Ubaidur R, Hossain SMI. Violence against women and its impact on women's lives—some observations from Bangladesh. J Fam Welfare 2001;46:12–24 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates LM, Schuler SR, Islam F, et al. Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2004;30:190–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Commission on Social Determinants of Health Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuler SR, Hashemi SM. Credit programmes, women's empowerment and contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plan 1994;25:65–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashemi SM, Schuler SR, Riley AP. Rural credit programmes and women's empowerment in Bangladesh. World Dev 1996;24:635–53 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khandker SR. Fighting poverty with microcredit: experience in Bangladesh. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuler S, Hashemi S, Riley A. The influence of women's changing roles and status in Bangladesh's fertility transition: evidence from a study of credit programmes and contraceptive use. World Dev 1997;25:563–75 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayoux L. Women's empowerment and microfinance programmes: strategies for increasing impact. Dev Pract 1998;8:235–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNFPA Microcredit Summit Campaign From microfinance to macro change: integrating health education and microfinance to empower women and reduce poverty. New York: Microcredit Summit Campaign and the United Nations Population Fund, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed SM. Intimate partner violence against women: experiences from a woman-focused development programme in Matlab, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 2006;23:95–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomized trial. Lancet 2006;368:1973–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Badal SH. Men's violence against women in rural Bangladesh: undermined or exacerbated by microcredit programmes? Dev Pract 1998;8:148–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Nobel Peace Prize for 2006. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2006/press.html (accessed 10 Oct 2012)

- 19.Koenig MA, Ahmed S, Hossain MB, et al. Women's status and domestic violence in rural Bangladesh: individual- and community-level effects. Demography 2003;40:269–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. STROBE statement. http://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed 13 Jan 2012)

- 21.Kishor S, Johnson K. Profiling domestic violence: a multi-country study. Calverton, MD: ORC Marcro, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss M. Measuring intra-family conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scales. In: Strauss MA, Gelles RJ. eds. Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8145 families. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1998: 29–47 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports no. 6. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston HB, Naved RT. Spousal violence in Bangladesh: a call for a public-health response. J Health Popul Nutr 2008;26:366–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuler S, Hashemi S, Riley P, et al. Credit programs, patriarchy and men's violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med 1996;43:1729–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhuiya A, Sharmin T, Hanifi SMA. Nature of domestic violence against women in a rural area of Bangladesh: implication for preventive interventions. 2003;21:48–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Kapur NA, et al. Violence against wives, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection among Bangladeshi men. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:211–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naved RT, Azim S, Bhuiya A, et al. Physical violence by husbands: magnitude, disclosure and help-seeking behavior of women in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:2917–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salam A, Alim A, Noguchi T. Spousal abuse against women and its consequences on reproductive health: a study in the urban slums in Bangladesh. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:83–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naved RT, Rimi NA, Jahan S, et al. Paramedic-conducted mental health counselling for abused women in rural Bangladesh: an evaluation from the perspective of participants. J Health Popul Nutr 2006;27:477–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.