Abstract

Background

Moderate intensity physical activity in women with breast cancer has been reported to improve physical and psychological outcomes. Yet, initiation and adherence to a routine physical activity program for cancer survivors after therapy may be challenging.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine the feasibility and effect of a community-based exercise intervention on physical and psychological symptoms and quality of life (QOL) in breast cancer survivors.

Methods

A one group pre-post test design was used to evaluate a thrice weekly, 4 to 6 month supervised exercise intervention on symptoms and QOL. Data were collected at baseline and end of the intervention, using the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Checklist, the Symptom Distress Scale, Centers for Epidemiology Scale for Depression and the Medical Outcomes Short Form.

Results

There were 26 participants with an average age of 51.3 years (SD=6.2) and most were married, well educated and employed. The intervention was delivered at 3 community fitness centers and adherence ranged from 75%-98%. Vasomotor, musculoskeletal, and cognitive symptoms were common but only muscle stiffness, fatigue and depression significantly changed over time (p=0.04, p =0.05 p=0.01 respectively). QOL improved significantly in the areas of physical, emotional and social function, pain, vitality and mental health.

Conclusions

Providing an exercise intervention in the community where women live and work is feasible and improves physical, psychological and functional well-being.

Implications for Practice

Exercise is a key component of cancer rehabilitation and needs to be integrated into our standard care.

Introduction

Physical activity and exercise interventions in women with breast cancer have been reported to improve psychological adjustment, physical functioning, cardiovascular fitness, body composition and emotional well-being; lower levels of fatigue, depression, anxiety; and help maintain a healthy weight 1-5. QOL and health related quality of life (HRQOL) have been reported to significantly improve following moderate intensity physical activity 2, 4, 6-8, and routine physical activity may also translate into survival benefits 9.

Breast cancer patients, however, are not routinely receiving recommendations for adopting healthy lifestyle behaviors and cite barriers to exercise such as fatigue, competing daily responsibilities and scheduling challenges 10, 11. Yet, there is a strong body of evidence from studies with breast cancer survivors on the safety and benefits of routine physical activity after therapy 12. There is a need for comprehensive cancer rehabilitation that addresses physical, psychological, vocational and social functioning 13. Such rehabilitation programs for survivors should include management of persistent symptoms, prevention of late treatment effects, risk reduction of co-morbid illness and health promotion 13-17. Dissemination of rehabilitation programs to communities where the majority of cancer survivors live and work is an essential component to achieving quality survivorship care 13.

Methods

This paper reports the findings on the feasibility of a community-based exercise intervention and effect on physical and psychological symptoms and QOL in a group of breast cancer survivors. A pilot study was conducted to evaluate a three times per week, 4 to 6 month supervised exercise intervention on bone mass, weight, body composition, physical and psychological symptoms and quality of life (QOL). We used a one group pre-post test design and participants were recruited through a comprehensive cancer center, private oncology office practices and notices in community newspapers. Eligible subjects were women diagnosed with Stage I or II breast cancer who completed primary and/or adjuvant chemotherapy ≤36 months from date of enrollment and were either peri-menopausal or postmenopausal at time of study entry. Women needed to be English speaking, able to complete questionnaires, give informed consent and be physically able to participate, the latter verified by signed physician approval. The study was approved by the University's Human Subject Review Committee. A detailed description of the study, data analysis and the findings of the primary outcomes (bone, weight , body composition) have been published 18.

Procedures

The research team partnered with community fitness centers to enhance feasibility and promote a practical approach to exercise adherence by selecting fitness facilities close to where women lived and/or worked. Three fitness centers located in different communities were selected based on their geographic proximity to recruitment patterns of women who qualified as eligible and consented to participate in the study. . Fitness centers agreed to allow the research staff to implement the intervention at their center. A dedicated area of the gym was provided with sufficient number of treadmills for the blocks of time scheduled for the study. Participants had fitness center memberships, which were subsidized by the centers in support of the research. A certified master's prepared exercise physiologist, a key member of the research team, trained and monitored the study interventionists. The interventionists had various educational preparation in exercise physiology but all had at least one basic training certification. The interventionists supervised the participants at each visit in the community fitness centers. Once women agreed to participate and signed consent, exercise schedules were then tailored to participants reported availability and groups were geographically assigned to the most convenient fitness center location. Using the concept of social support, the exercise protocol offered 2 hour blocks of time 5 days a week to promote adherence through participant interaction. The intervention protocol was a progressive aerobic exercise program on a treadmill using a weight belt and a heart rate monitor watch. Target heart rates were calculated for each participant based on clinical data of their resting heart rates taken at baseline visits in the hospital research unit. The intervention included routine stretching exercises, as recommended by the American College Sports Medicine 19, in combination with a standard 5 minute warm up and cool down period before and after the time on the treadmill. Because less than 25% of the women ever reported having a gym membership prior to study, a training session was developed by the research team. The training session included specific components of a stretching program, a description of target heart ranges and the use of the heart rate monitor watch, and the programming of treadmills for safety and protocol progression. Weeks 1-4 were dedicated to training weeks, progressing from 10-20 minute treadmill sessions three times per week progressing to 30 minutes three times per week in target heart range of 60%-65%. From weeks 5 through 16 or 24, women performed 45 minute sessions on the treadmill sessions to achieve maximal heart rate of 75%. Heart rate monitoring and data collection were conducted simultaneously. Participants reported their heart rates to the interventionist every 5 minutes. Interventionists' maintained exercise consistency by adjusting the speed and grade of the treadmills to ensure participants were in target range during the treadmill sessions. This reporting method kept participants engaged and also provided quality assurance. Details on the weight loading have been previously described 18.

Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected at baseline, 16 and 24 weeks during the participant's visit at the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation Hospital Research Unit. Demographic data were recorded on an investigator designed form. Physical and psychological symptom distress and QOL were rated by the participants using the Breast Cancer Symptom Checklist (BCPT), the Symptom Distress Scale (SDS), the Center for Epidemiology Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Medical Outcomes-Short Form (MOS-SF 36). Medical data were collected from the participant's outpatient clinic or office record.

Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Symptom Checklist is a 42 item list of common physical and psychological symptoms 20, 21. The respondent is asked if she has been bothered by any of the symptoms over the past 4 weeks with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The original instrument indicted a response for presence of the symptom as yes or no. For this study, 0 indicated absence of symptom and severity scores from 1-4 indicated presence of the symptom with distress rated from a little (1) to extremely bothered (4). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses have been conducted with findings suggesting eight symptom clusters or factor structures, although with minor variation on item loading 21-23. Coefficient alphas ranged from 0.55 to 0.87 23 and discriminate validity was established comparing the BCPT with the MOS SF-36 22, 23.

Symptom Distress Scale

Symptom distress is the perceived discomfort of a symptom by a person, regardless of etiology of the symptom 24. The instrument consists of 11 symptoms: nausea , pain, fatigue, appetite, concentration, outlook, insomnia, bowel pattern, appearance, breathing, and cough. Two items were added for this study: sexual interest and weight change. Symptom distress is rated on a 5 point scale (1-mild distress to 5=very distressful).This instrument has been extensively used in research and has established validity and reliability across 47 studies, internal consistency has been reported to range from 0.70-0.92 25.

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item scale designed to assess depressive symptoms 26. Scale scores range from 0 to 60, higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Items are scored on a 4 point scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). The reliability and validity are well established 26, 27.

Medical Outcomes Study-SF (MOS-36) is an assessment of self reported functional ability and has been also conceptualized as a QOL measure. It consists of eight subscales (physical functioning, role function-physical, bodily pain, social functioning, emotional well being, role functioning-emotional, energy/fatigue and general health perceptions) 28. Each subscale is scored from 0-100 with the higher score indicating better functioning. It also provides an overall measure of general health or quality of life. Validity and reliability have been established and internal consistency reliability coefficients have been reported ranging from 0.62 to 0.96.

Data Analysis

Data were entered into an ACCESS® database. Analyses were carried out using SAS® v9.2. Instruments were scored in accordance with instructions specific to each instrument. Unless directed differently by scoring instructions, missing values were replaced by mean imputed values across items if 15% or fewer items were missing. Repeated measures analyses were done using generalized estimating equations. Repeated measures analyses were done using mixed modeling; compound symmetry was used to model intra-class correlation. Assumptions of normality and constant standard deviation were assessed. Assumption of normality was marginally violated on some models, and was addressed by using transforms.

Results

Sample

Thirty-three women consented to participate, two never started and five women did not complete the study. Of those who failed to complete, 3 dropped out for non-study injuries, one for a breast cancer recurrence and one for job related reasons. Of the 26 evaluable women, the average age was 51.3 years (SD=6.2) and most were married, well educated and employed (Table 1). Initially, the study was funded for 16 weeks but additional funds were secured, allowing women to continue for a total of 24 weeks. Due to the timing of additional funding, 24/26 women were offered extension to 24 weeks of the protocol and 79.2% (N=19) accepted. All subjects had completed primary and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer and 62% were currently on endocrine therapy with Tamoxifen or an Aromatase Inhibitor. Adherence ranged from 75%-98% with an average attendance of 88.2% for all sessions 18.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics (N=26).

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 26 | 100 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 20 | 77.0 |

| Single | 3 | 11.5 |

| Divorced | 3 | 11.5 |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate | 8 | 31.0 |

| College graduate | 10 | 38.0 |

| Post-graduate | 8 | 31.0 |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time/part-time | 23 | 88.0 |

| Not employed | 3 | 12.0 |

| Annual Household Income | ||

| < $40,000 | 2 | 8.0 |

| $40,000-80,000 | 5 | 19.5 |

| > $80,000 | 15 | 57.5 |

| Not reported | 4 | 15.0 |

Physical and Psychological Symptom Distress

The 42 item BCPT Checklist 21-23 was used to identify the prevalence and severity or perceived distress from subjects. At baseline, 15 of the 42 symptoms were reported by ≥ 30% of women (range 30%-85%) with average severity ratings ranging from 1.4 to 2.4 (Table 2). The majority of reported symptoms fell into the general categories of vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats, early awakenings), musculoskeletal symptoms (joint pains, aches/pains, muscle stiffness, swelling hands), cognitive changes (difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness) , bodily changes (unhappy with appearance, weight gain), and symptoms of atrophic vaginitis (vaginal dryness, dyspareunia). Vasomotor symptoms were the most commonly reported (> 50% of subjects) and hot flashes were associated with the highest mean severity ratings which did not change over time (Table 2). Of the musculoskeletal symptoms, more women reported aches/pains over time but with lower severity scores while fewer women reported hand swelling, joint pains and muscle stiffness over time. Muscle stiffness, however, was the only symptom that significantly decreased over time (P=.04). Memory problems were reported more often than problems with concentration but both cognitive symptoms had relatively low average distress ratings (1.2-1.4). Body image, especially women's unhappiness with their appearance was reported by > 50% of women.

Table 2. Symptoms reported by ≥ 30% of Subjects and Mean Severity Ratingsa.

| Symptom | Frequency (%) | Mean Severity * (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Baseline | 16 wks | 24 wks | Baseline | 16 wks | 24wks | |

| Hot flashes | 85 | 84 | 89 | 2.3 (0.93) | 2.0 (0.94) | 2.1 (1.02) |

| Joint pains | 80 | 64 | 63 | 1.9 (0.75) | 2.0 (0.73) | 2.0 (0.95) |

| Muscle stiffness | 80 | 52 | 53 | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.0) |

| Unhappy with body | 76 | 68 | 58 | 2.4 (1.16) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.04) |

| Headaches | 52 | 50 | 37 | 1.7 (0.89) | 1.2 (0.52) | 1.8 (1.20) |

| Night sweats | 64 | 64 | 68 | 1.8 (1.17) | 1.7 (1.14) | 1.6 (1.12) |

| Forgetfulness | 62 | 60 | 74 | 1.4 (0.73) | 1.2 (0.41) | 1.3 (0.91) |

| Aches /pains | 60 | 72 | 78 | 1.9 (1.03) | 1.6 (0.77) | 1.5 (0.94) |

| Vaginal dryness | 52 | 50 | 37 | 2.2 (0.80) | 1.9 (0.99) | 1.9 (1.34) |

| Early awakening | 50 | 33 | 53 | 2.2 (1.02) | 2.7 (1.03) | 1.8 (0.91) |

| Concentration | 48 | 32 | 37 | 1.5 (0.79) | 1.3 (0.88) | 1.4 (0.79) |

| Weight gain | 40 | 36 | 16 | 1.8 (0.79) | 1.0 (0.50) | 3.3 (0.57) |

| Breast Sensitivity | 36 | 40 | 52 | 2.0 (1.32) | 2.1 (0.99) | 1.8 (1.03) |

| Hand swelling | 32 | 36 | 21 | 1.4 (0.52) | 1.3 (0.71) | 0.8 (0.50) |

| Dyspareunia | 30 | 24 | 16 | 2.0 (1.5) | 2.2 (1.17) | 2.0 (0.0) |

Severity rated from 1 (a little bothersome) to 4 (extremely bothersome)

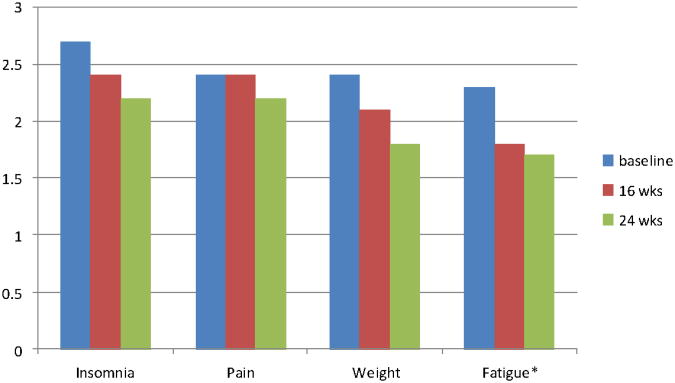

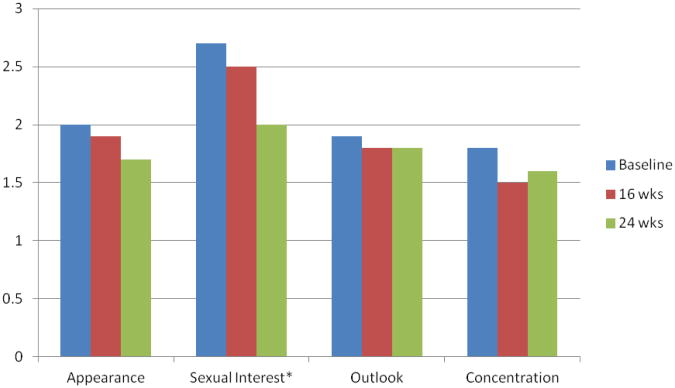

The Symptom Distress Scale was used to identify level of distress associated with 13 symptoms. Of the 13 symptoms, women rated cough, appetite, nausea, bowel and breathing symptoms as infrequent, not a problem or very mildly distress. The remaining 8 symptoms are depicted in Figure 1 (physical symptoms) and Figure 2 (psychological symptoms). Overall, women reported mild to moderate symptom distress and distress related to the common symptom of fatigue improved significantly over the course of the exercise intervention (P=.05).There were significant relationships between physical and psychological symptom distress. Fatigue was associated with insomnia (r=42, P=.003). concentration (r=.45, P=.001) and outlook toward the future (r=.26, P=.03). Distress over weight change was associated with concerns about appearance (r=.56, P=.001), a more negative outlook toward the future (r=.32, P=.006) and decreased sexual interest (r=.32, P=.005).

Figure 1. Physical Symptom Distress.

*p=0.05

Figure 2. Psychological Symptom Distress.

*p-0.08

Depression was measured by the CES-D 26. 27. The average depression score at baseline was 10.98 (8.58) which significantly decreased at 16 weeks (7.0 (SD=9.3), P=.01) and 24 weeks (7.0 (SD=7.7), P=.08). However, there was no significant change between 16 and 24 weeks, suggesting that the intervention had its effect on mood during the first 16 weeks which was sustained over time.

Functional Ability and Quality of Life

Physically, women significantly improved over time across the intervention, as measured by the subscales for physical function (P=.03) and vitality (P=.0001) (Table 3). Women also improved in the areas of emotional (P=.02), social functioning (P=.009) and mental health (P=.0005) (Table 3). Overall QOL improved before and after the exercise intervention despite a substantial percentage of women reporting symptoms (Table 2).

Table 3. Effect of Exercise on Functional Ability and Quality of Life (MOS-SF ).

| MOS-SF 36 Scales | Baseline Mean (SD) | 16 weeks Mean (SD) | 24 weeks Mean (SD) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Function | 86.2 (15.7) | 91.0 (7.9) | 92.6 (7.8) | P= .03 |

| Role-physical | 82.2 (22.7) | 91.8 (16.2) | 89.4 (16.8) | NS |

| Bodily Pain | 70.1 (18.4) | 77.5 (13.3) | 74.1 (19.3) | P=.06 |

| Health | 77.3 (18.0) | 78.5 (17.8) | 79.7 (16.0) | NS |

| Vitality | 53.1 (18.8) | 70.1 (17.7) | 70.5 (16.0) | P=.0001 |

| Social | 80.7 (21.8) | 89.9 (17.3) | 90.1 (16.4) | P=.009 |

| Role-emotional | 83.9 (17.1) | 90.3 (15.7) | 93.8 (13.5) | P=.02 |

| Mental Health | 70.9 (15.8) | 80.7 (16.7) | 82.0 (15.0) | P=.0005 |

| Physical Component Score | 51.7 (7.1) | 53.5 (4.5) | 52.7 (5.7) | NS |

| Mental Component Score | 46.8 (10.0) | 52.7 (10.2) | 53.9 (8.8) | P=.002 |

In summary, this aerobic exercise intervention over 4 to 6 months in breast cancer survivors resulted in improvements in physical function, fatigue, emotional and social well being and overall QOL. While women commonly reported symptoms, the level of symptom distress reported was in the mild to mild-moderate range. Limitations include the one group pre and post test design, a volunteer homogenous sample of women, a small sample size and diversity of time since treatment, although all women were within two years of finishing primary or adjuvant chemotherapy and 62% were currently on adjuvant endocrine therapy 18. In a one group design, it is unknown if outcomes would have improved with time, as there is no control group. However, this was only a 4-6 month intervention and it is unlikely that specific outcomes, such as physical function, would have improved without the intervention.

Discussion

Cancer patients transition into survivorship living with persistent physical and psychological symptoms and many are at risk for late treatment effects and co-morbid illness 29. Exercise is perceived as an integral component to cancer rehabilitation for cancer survivors and can improve physical, psychological and social functioning outcomes 12-15. Women report scheduling problems and managing everyday life as barriers to routine exercise. Exercise programs need to be available in the communities where women live and work to optimize participation, integration into daily life and a sustained commitment. The YMCA Livestrong program 11 is a good example of dissemination of cancer rehabilitation into the community 13. For communities that do not have easy access to the YMCA programs, partnering with physical therapists and fitness centers, especially those with certified cancer personal trainers, are viable options to promote access to structured exercise programs for survivors. Structure, supervision, location and social support are factors that contribute to the adoption and maintenance of a routine physical activity program 30, 31. In the present study, the supportive relationships that the women developed exercising together in the assigned blocks of time may have contributed to the high adherence rates and possibly to the QOL outcomes.

The findings from this study demonstrated that adoption of regular exercise by breast cancer survivors in a community setting is feasible, demonstrated by high adherence rates. The findings also suggest that selected symptoms, such as depression and fatigue, improve with exercise. Other symptoms commonly reported by women in the first several years following therapy may or may not be affected by exercise. The symptoms reported by women in this study are similar to other published data that used the BCPT for symptom assessment 32-34. The majority of women in this study reported vasomotor symptoms (>80%), but 62% of this sample were on either Tamoxifen or an Aromatase inhibitor (AI). Ganz and colleagues 32 reported a 68% incidence of hot flashes among women in the age range of 45-51 years but only 20% of those women were taking Tamoxifen, in comparison to a higher incidence (73.5%) reported in a sample of women for whom 45% were taking Tamoxifen 33. There are no known data on the effect of exercise on vasomotor symptoms in breast cancer survivors 1, 2 but for postmenopausal women without a cancer diagnosis, the findings are conflicting ranging from no effect to some decrease in symptoms 35, 36. The incidence of vaginal dryness (46%-55%) 32, 34 and dyspareunia (32%-40%) 32-34 were consistent with the experience of women in this study (Table 2). Musculoskeletal symptoms of joint pains and muscle stiffness were more frequent in this study at baseline (80%) compared to women of similar age, but who were not on an AI 32, although these symptoms decreased over time during the exercise intervention. Musculoskeletal symptoms associated with AI therapy are well established and often a reason for discontinuation. Exercise has been cited as a non-pharmacologic intervention to improve strength and maintain joint mobility but has not been studied related to AI symptom relief 37-39. One study 40, used the Western Ontario and MacMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) to assess lower extremity join function and pain in a 12 week physical activity intervention in 41 sedentary breast cancer survivors, all of whom were on adjuvant endocrine therapy and, on average, 3 years since surgery. Improvement in joint function in the intervention versus usual care group was reported (P=.05) but there were no significant differences in joint pain or joint stiffness 40.

Forgetfulness was reported by 62%-74% over the three time points across the 6 months of this study, which is similar to other published research (62%-79%) 32, 33. Changes in cognitive function with chemotherapy 41 and endocrine therapy 42, 43 are well established in breast cancer survivors. Exercise as a targeted non-pharmacologic intervention has not been studied for its potential effect on cognitive functioning 44. “Unhappy with appearance” is the BCPT item that addresses body image and was reported by a high percent of women at baseline (76%) which is consistent with other investigations. Distress ratings for appearance >2.0 was also similarly reported by Alfano and colleagues 33. Body image problems have been associated with type of surgery, chemotherapy side effects (e.g. hair loss), weight change and poorer mental health 45. In this study, the item “unhappy with appearance” was significantly associated with weight change (P=.001). Although this study used aerobic exercise, resistance exercise can improve body composition, even without weight loss, resulting in a potentially better body image.

Depression scores declined significantly over time following the exercise intervention in this study. Duijts and colleagues 6 reported an effect size of -.26 (p=0.016) for the effect of exercise on depression, which is consistent with the previously reported effect size of -.30, although that was not statistically significant (P=.10) 2.

Fatigue is one of the most common cancer treatment related symptoms and there is a large body of research supporting the positive effects of exercise on preventing and/or decreasing the incidence and severity of fatigue 2, 46, which supports the proposed relationship of fatigue and exercise 47. As fatigue interferes with everyday function and QOL, exercise should be recommended routinely in practice for all cancer patients, during and after therapy.

Exercise improves QOL 8, 48 and the effects are greater with moderate intensity physical activity over a longer duration 7. In two meta-analyses 2, 6, statistically significant results were reported for exercise on QOL with an effect size of 0.29, indicating a small to moderate positive effect. In this study, the MOS-SF-36 was used to measure functional ability and QOL. The 8 subscale scores and the two component scale (physical and mental health) scores at baseline were highly consistent with those reported by others in breast cancer survivors ranging from 6 months to 5 years post-treatment 28, 49, 50. The scores, however, in the study reported here, all improved after the exercise intervention and the majority reached statistical significance (Table 3).

Implications for Practice and Research

The findings from this study confirm that adoption of a routine pattern of exercise is feasible for cancer survivors. However, survivors need explicit prescriptions for health promotion 12, 13 and strategies to overcome barriers. In addition, the findings provide support for the benefits exercise on fatigue, depression, and QOL, and as previously reported, exercise maintains weight and bone mass in women who are at otherwise at risk for weight gain and bone loss 18. Combined with the effects of exercise on cardiopulmonary function and the growing evidence to support a potential survival advantage for cancer patients 9, exercise should be included as part of standard care 51. Nurses need to identify community fitness center partners, certified fitness professionals and physical therapists to work with cancer patients and survivors 12, 52. Rehabilitation professionals should be well educated on the sequelae of the various types of cancer treatment so that services can be accurately targeted 12. Health promotion for cancer patients transitioning to survivorship after therapy is completed is an essential nursing responsibility and needs to include information, evidence based recommendations and identified resources.

Implications for future research include larger randomized controlled trials with population based samples to increase generalizability. Longer duration exercise programs monitoring adherence over time, follow-up for sustainability of intervention effects and exercise interventions with more diverse cancer survivor populations are also needed. It is known that older adults benefit from exercise and there is a gap in our research for the role of exercise in rehabilitation of the older cancer survivor who may also be at greater risk for co-morbid health conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paige Woodward and Daniele Avila for their contributions to the analysis of the quality of life data; Marie LaGasse, Barbara Womer and Linda Dickey-Saucier for their roles as exercise interventionists in the study and the local community fitness centers who supported the research.

This study was supported in part by the American Cancer Society Professorship in Oncology Nursing, NIH/NINR 1P20NR07806-01 and by CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.”

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim C, Kang D, Park J. A meta-analysis of aerobic exercise interventions for women with breast cancer. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31(4):437–461. doi: 10.1177/0193945908328473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong DY, Ho JW, Hui BP, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SS, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e70. doi:101136/bmje70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfano CM, Smith AW, Irwin ML, Bowen DJ, Sorensen B, Reeve BB, et al. Physical activity, long term symptoms and physical health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective analysis. J Cancer Surv. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg SA, van Beurden M, Aaronsoon NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors-a meta-analysis. Psycho-oncol. 2011;20:115–126. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrer RA, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT, Ryan S, Pescatello LS. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:32–47. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knobf MT, Musanti R, Dorward J. Exercise and quality of life outcomes in patients with cancer. Seminars Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(4):285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballard-Barbash R, Freidenreich CM, Courneya KS, Siddiqi SM, McTiernan A, Alfano CM. Physical activity, biomarkers and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(11):815–840. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers LQ, Matevey C, Hopkins P, Shah P, Dunnington G, Courneya KS. Exploring social cognitive theory constructs for promoting exercise among breast cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(6):462–473. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajotte EJ, Yi JC, Baker KS, Gregerson L, Leiserowtiz A, Syrala KL. Community-based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surv. 2012;6:219–228. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2010;42(7):1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alfano CM, Ganz PA, Rowland J, Hahn EE. Cancer survivorship and cancer rehabilitation: revitalizing the link. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(9):904–906. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binkley JM, Harris SR, Levangie PK, Pearl M, Guglielmino J, Kraus V, Rowden D. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment side effects and the prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(8suppl):2207–2016. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger AM, Gerber LH, Mayer DK. Cancer-related fatigue. Cancer. 2012;118(8suppl):2261–2269. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demark-Wahnefreid W, Campbell KL, Hayes SC. Weight management and its role in breast cancer rehabilitation. Cancer. 2012;118(8suppl):2277–2287. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knobf MT, Coviello J. Lifestyle interventions for cardiovascular risk reduction in women with breast cancer. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2011;7:250–257. doi: 10.2174/157340311799960627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knobf MT, Insogna K, DiPietro L, Fennie K, Thompson AS. An aerobic weight-loaded pilot exercise intervention for breast cancer survivors: bone remodeling and body composition outcomes. Biol Res Nurs. 2008;10(1):34–43. doi: 10.1177/1099800408320579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th. Philadelphia: ACSM; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Day R, Ganz PA, Costantino JP, Cronin WM, Wickerham DL, Fisher B. Health related quality of life and tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention: a report from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2659–2669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA. The BCPT symptom scales: a measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:448–456. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella D, Land SR, Chang C, Day R, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, Ganz PA. Symptom measurement in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) (P-1): psychometric properties of a new measure of symptoms for mid-life women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:515–526. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9682-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terhorst L, Blair-Belansky H, Moore PJ, Bender C. Evaluation of the psychometric properties f the BCPT Symptom Checklist with a sample of breast cancer patients before and after adjuvant therapy. Psycho-oncol. 2011;20:961–968. doi: 10.1002/pon.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCorkle R, Young K. Development of a symptom distress scale. Canc Nurs. 1978;1:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCorkle R, Cooley M, Shea J. Unpublished. Yale School of Nursing; 2009. A user's manual for the symptom distress scale. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research. 1978;2:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Sherborne CD. The MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivors: Lost in Transition. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Mackey JR, Fredenreich CM, et al. Predictors of supervised exercise adherence during breast cancer chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2008 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318168da45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner J, Hayes S, Ruel-Hirche H. Improving the physical status and quality of life of women treated for breast cancer: a pilot study of a structured exercise intervention. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:141–146. doi: 10.1002/jso.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4184–4193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, Reeve BB, Bowen DJ, Baumgartner KB, et al. Psychometric properties of a tool for measuring hormone-related symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncol. 2006;15:985–1000. doi: 10.1002/pon.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;23(15):3322–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aiello EJ, Yasui Y, Tworoger SS, Ulrich CM, Irwin M, Bowen D, et al. Effect of a year long, moderate intensity exercise intervention on the occurrence and severity of menopause symptoms in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2004;11(4):383–388. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000113932.56832.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miolanene JM, Mikkola TS, Raitanene JA, Heinonen RH, Tomas EI, Nygard C, Luoto M. Effect of aerobic training on menopausal symptoms-a randmonized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(6):691–696. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31823cc5f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorne C. Clinical management of arthralgia and bone health in women undergoing adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Curr Opinion Oncol. 2007;19(suppl1):S19–S28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dent SF, Gaspo R, Kissner M, Pritchard KI. Aromatase inhibitor therapy: toxicities and management strategies in the treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:295–310. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park S, Knobf MT, Sutton K. Etiology, assessment and management of aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal symptoms. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(3):260–266. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.260-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Markwell S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity and health outcomes three months after completing a physical activity behavior change intervention: persistent and delayed effects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Pre. 2009;18:1410–1408. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart A, Bielajew C, Collins B, Parkinson M, Tomiak E. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in women treated for breast cancer. Clin Neuropsychologist. 2006;20:76–89. doi: 10.1080/138540491005875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer JL, Trotter T, Joy AA, Carlson LE. Cognitive effects of Tamoxifen in premenopausal women with breast cancer compared to healthy controls. J Cancer Surv. 2008;2:275–282. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bender CM, Sereika SM, Brufsky AM, Ryan CM, Vogel VG, Rastogi P, et al. Memory impairment with adjuvant anastrozole versus tamoxifen in women with early-stage breast cancer. Menopause. 2007;14(6):995–998. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318148b28b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Ah D, Jansen C, Allen DH, Schiavone RM, Wulff J. Putting evidence into practice: evidence-based interventions for cancer and cancer treatment-related cognitive impairment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(6):607–613. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.607-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D'Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Pscyho-oncol. 2006;15:579–594. doi: 10.1002/pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eaton LH, Tipton JM. Putting Evidence into Practice Improving Oncology Patient Outcomes. Oncology Nursing Society; Pittsburgh: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Mahid S, Gray DP. A biobehavioral model for the study of exercise interventions in cancer –related fatigue. Biol Res Nurs. 2009;10(4):381–391. doi: 10.1177/1099800408324431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Brown LM. Meta-analysis of quality-of-life outcomes from physical activity interventions. Nur Res. 2009;58(3):175–183. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318199b53a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganz PA, Coscarelli A, Fred C, Kahn B, Polinsky ML, Peteren L. Breast cancer survivors:psychosocial concerns and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;38:183–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01806673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bardwell WA, Major JM, Rock CL, Newman VA, Thomson CA, Chilton JA, Dimsdale JE, Pierce JP. Health-related quality of life in women previously treated for early stage breast cancer. Psycho-oncol. 2004;13:595–604. doi: 10.1002/pon.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giovannucci EL. Physical activity as a standard cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(11):797–799. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campbell KL, Pusic AL, Zucker DS, McNeely ML, Binkley JM, Cheville AL, et al. A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation:function. Cancer. 2012;118(8suppl):2300–2311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]