Abstract

Mexican Americans are one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States, yet we have limited knowledge regarding changes (i.e., developmental trajectories) in cultural orientation based upon their exposure to the Mexican American and mainstream cultures. We examined the parallel trajectories of Mexican American and mainstream cultural values in a sample of 749 Mexican American adolescents (49% female) across assessments during the fifth grade (approximately 11 years of age), the seventh grade (approximately 13 years of age) and the tenth grade (approximately 16 years of age). We expected that these values would change over this developmental period and this longitudinal approach is more appropriate than the often used median split classification to identify distinct types of acculturation. We found four distinct acculturation trajectory groups: two trajectory groups that were increasing slightly with age in the endorsement of mainstream cultural values, one of which was relatively stable in Mexican American cultural values while the other was declining in their endorsement of these values; and two trajectory groups that were declining substantially with age in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values, one of which was also declining in Mexican American cultural values and the other which was stable in these values. These four trajectory groups differed in expected ways on a number of theoretically related cultural variables, but were not highly consistent with the median split classifications. The findings highlight the need to utilize longitudinal data to examine the developmental changes of Mexican American individual’s adaptation to the ethnic and mainstream culture in order to understand more fully the processes of acculturation and enculturation.

Introduction

The rapidly increasing absolute and relative size of several ethnic minority populations in the United States (particularly Mexican Americans: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012) is noteworthy given the empirical evidence that increased exposure to the mainstream culture of the United States may be associated with increased negative behavioral and mental health outcomes for some ethnic minority youth (e.g., Rogler, Cortes, & Malgady, 1991; Samaniego & Gonzalez, 1999). Some ethnic minority youth may be at risk for negative outcomes (e.g., internalizing problems, externalizing problems, academic failure, and drug and alcohol abuse) because the demands to adapt to both the mainstream and ethnic cultures require adherence to the behavioral expectations and values of the ethnic culture and adherence to the behavioral expectations and values of the mainstream culture (e.g., Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002; Szapocznik, & Kurtines, 1993). However, some authors have suggested that a strong connection to the ethnic culture may be protective and suppress these negative effects because these youth may be less differentiated from their parents, less likely to experience family conflict, and more likely to receive strong social support from the family (e.g., Atzaba-Poria & Pike, 2007; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006; Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993; Vega & Gil, 1999). Hence, understanding the nature of this dual cultural adaptation process is critical to understanding the potential risks, and protections, that may be associated with these demands.

Although some (e.g., Berry 2006) describe this dual cultural adaptation under the rubric of acculturation, we describe this dual cultural adaptation as occurring through the processes of acculturation and enculturation (e.g., Gonzales et al., 2002) to differentiate those forces promoting mainstream adaptation from those promoting ethnic adaptations. Acculturation is the process of the adaptation to the mainstream culture, while enculturation is the process of adaptation to the ethnic culture. Although acculturation and enculturation processes are separable, they are not independent or orthogonal, and they lead to outcomes in which an individual may achieve any combination of levels along each dimension. These dual-axis processes of adaptation lead to change over time in a wide array of psychosocial dimensions including cultural knowledge, behaviors, beliefs, attitudes, and values (e.g., Berry, 2006; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Félix-Ortiz, Newcomb, & Myers, 1994; Gonzales et al., 2002; LaFramboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993; Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, & Wong, 2002). Furthermore, these adaptations occur through normal developmental and socialization processes (broadly defined) that unfold throughout the lifespan of ethnic minorities who have immigrated recently, as well as those that have been in the United States for several generations. The resulting developmental changes in culturally related knowledge, behaviors, beliefs, attitudes, and values become an integral part of the ethnic minority individuals’ ethnic and mainstream social identities depending on the culture with which they are associated. Much, but not all, ethnic socialization occurs in the family and ethnic community. Much, but not all, mainstream socialization occurs in schools, mainstream community, and media. Because of the variability in the cultural contexts in which ethnic minority youth live (e.g., school and neighborhood ethnic composition, language spoken in the home, the availability of ethnically related services and products), there is considerable variability in the degree of ethnic and mainstream socialization pressures they experience and in their connection to the ethnic and mainstream cultures. This variability has led many theorists to believe that there are qualitatively different types of dual cultural adaptations and associated developmental trajectories experienced by ethnic minority youths (e.g., Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993; Tadmor & Tetlock, 2006).

Unfortunately, the research literature examining these dual cultural adaptation processes has been limited in several ways. First, although these processes often are described as resulting in changes in response to exposure to both the mainstream and ethic cultures, most of the studies on this topic have been conspicuously cross-sectional and have relied on single point in time assessments. Hence, most of these studies do not directly assess changes in cultural orientation associated with age related changes in exposure to the ethnic culture and the mainstream culture. The few examinations of the longitudinal trajectories associated with these types of adaptations by ethnic minority individuals generally have investigated only one of these processes (often enculturative changes) and/or examined these changes in very select samples (e.g., clinical patients, college students or juvenile offenders, etc.: Altschul, Oyserman, & Bybee, 2006; French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Kiang, Witkow, Baldelomar, & Fuligni, 2010; Knight, Losoya, Cho, Chassin, Williams, & Cota-Robles, in press; Pahl & Way, 2006; Schwartz et al, in press; Syed & Azmitia, 2009). The primary purpose of the present study was to examine the longitudinal trajectories of developmental change associated with acculturative and enculturative adaptation processes in a relatively representative sample of Mexican American adolescents.

Second, much of this research has focused on a limited range of behavioral indicators, such as language use and affiliation patterns, that may be somewhat, if not strongly, determined by the adults (i.e., parents and teachers) in the adolescent’s life. Therefore, we examine the parallel trajectories of change in the endorsement of values relatively more often associated with the Mexican American culture (i.e., referred to as Mexican American cultural values) and values relatively more often associated with the mainstream culture of the United States (i.e., referred to as mainstream cultural values) among Mexican American adolescents across three assessments over a six-year time period. The specific Mexican American cultural values (i.e., Familism-Support, Familism-Obligations, Familism-Referents, Respect, and Religiosity) and mainstream cultural values (i.e., Material Success, Independence and Self-Reliance, and Competition and Personal Achievement) examined in this study were identified as associated with the respective culture by a sequence of focus groups of Mexican American adolescents, mothers, and fathers (Knight, Gonzales, Saenz, Bonds, Germán, Deardorff, Roosa, & Updegraff, 2010). We decided to examine the trajectories of change in culturally related values, and across this age span, because this is a time period during which there are substantial changes in their exposure to the mainstream culture (e.g., Daniel et al., 2012). Although there is considerable variability during the elementary school years, Mexican American children are more likely to attend neighborhood schools that have a relatively higher proportion of Mexican American students, teachers, and staff. As they transition into middle schools and eventually high school they are likely to experience an increase in the proportion of students and adults from a more mainstream background. These transitions represent a developmental time period during which adolescents are increasingly being influenced by peers and during which familial influence may decease somewhat (Brown, 1990; Knight et al., 2009), and they increasingly experience a wider variety of immediate contexts to which they must adapt. The internalization of such values ultimately becomes an important guide to behavior in a wide range of contexts (e.g., Schwartz 1999). Because of the great variability, and sometime novelty, in the contexts to which they are exposed, it is likely that they increasingly rely on the values they have internalized in their ethnic and mainstream identities to guide them to appropriate behavioral responses in these contexts (e.g., Daniel, Schiefer, Möllering, Benish-Weisman, Boehnke, & Knafo, 2012). Second, the internalization of such values very accurately reflects the psychological state of the adolescent experiencing the dual-cultural adaptation demands associated with the processes of acculturation and enculturation. Furthermore, adolescence is a developmental period during which the normative processes of identity development (Erikson, 1968) lead minority adolescents to become more aware of the importance of ethnic group membership and to explore their ethnic origins and commit to that ethnic group (e.g., Phinney, 1990; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). During these developmental transition periods, social identity and self-categorization processes (e.g., Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987) are likely to lead Mexican American youth to internalize values associated with Mexican American culture in part because of their increasing commitment to, and exploration of, their ethnic group membership. While younger children may behave in accordance with the cultural values of the parents and other socialization agents often because of the sanctions (both positive and negative) associated with behaving accordingly; adolescents may be abstracting value rules from their socialization experiences and internalizing these values into their system of social identities so that they become self-chosen guides for behavior (e.g., Knight, Berkel, Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales, Ettekal, Jaconis, & Boyd, 2011). Indeed, there is evidence that late childhood or early adolescence is a time at which important changes in reasoning and values begin to emerge (e.g., Daniel et al, 2012; Eisenberg, Miller, Shell, McNalley, & Shea, 1991).

A third limitation often associated with the preponderance of the studies that rely on single-point-in-time assessments is the frequent use of the median-split procedure to classify individuals into different types of acculturation/enculturation groups. The use of sample specific median-splits can be very problematic because the inherent positive skew of many of the indicators of cultural orientation (i.e., measures of acculturation, ethnic identity, ethnic pride, cultural values, etc.) often have median scores that are relatively high (i.e., often nearly a 4.0 or above on a five-point response scale) and the respondents that are below this median are classified as though they are low even though very few may actually score low on these actual response scale (Coatsworth et al., 2005; Knight, Vargas-Chanes, Losoya, Cota-Robles, Chassin, & Lee, 2009). In contrast, we rely on person-centered analytical methods to identify individuals’ longitudinal changes in these culturally related values as they transition from the elementary school years through middle schools and high school years. We also identify groups of Mexican American adolescents who are experiencing similar trajectories of change, and we do so without imposing an arbitrary dichotomization like a median-split. We also examine the association of the resulting trajectory groups to a number of variables reflecting adolescents’ cultural adaptations (i.e., the adolescents reported ethnic pride, ethnic identity, perceptions of ethnic discrimination, biculturalism, and use of the Spanish and English languages) and their gender and nativity.

A secondary purpose of this study is to examine the relationship of these longitudinal trajectories to the single-point-in-time median-split classifications (e.g., Berry, 2007; Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, 1980) in which ethnic minority participants have been classified as “bicultural” if they score above the median on a focal assessment of ethnic cultural orientation and above the median on an assessment of mainstream cultural orientation. The other three quadrants created by a median split on ethnic orientation and mainstream orientation have been labeled “assimilated” (high mainstream, low ethnic); “separated” or “alienated” (high ethnic, low mainstream); and “marginalized” (low on both). Although there has been some debate regarding whether a mid-scale split might be more conceptually defensible (e.g., Arends-Tόth & van de Vijver, 2006), the empirical evidence indicates that the dichotomization of a naturally continuous variable results in: lower measurement reliability and the associated loss of effect size and power, spurious relations and the overestimation of effect sizes in analyses with multiple independent variables, overlooking non-linear relations (MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002). Indeed, analyses that dichotomized continuous variables perform well only when the: underlying distribution of the variable is strongly categorical, the proportion of participants assigned to each dichotomized categories matches the proportion found in latent variable analyses, and the continuous measure is highly reliable (DeCosta, Iselin, and Gallucci, 2009). These problems may well be why recent studies that relied on a person-centered approach (Coatsworth et al., 2005; Knight, et al., 2009), one of which was also longitudinal (Knight, et al., 2009), have not found strong evidence of these four acculturation/enculturation types that result from the median-split procedure. However, these person-centered studies also relied on select samples of adolescents, either youth in an intervention program or juvenile delinquents.

The Current Study

Researchers have suggested that the dual cultural adaptations that ethnic minority youth experience during their routine contact with the ethnic and mainstream cultures may lead to changes in cultural knowledge, behaviors, beliefs, attitudes, and values over time; and that these changes may create either risk factors for, or protective factors against, negative outcomes. Hence, the present study was designed to identify groups of Mexican American youth demonstrating distinct trajectories of change in Mexican American and mainstream cultural values across a seven year developmental time frame. Because the limited longitudinal research on these dual cultural adaptation processes have not supported the four-fold typologies identified by the median-split methodologies, we expected to find a number of distinct trajectory groups but did not have a priori expectations regarding the exact nature of these groups. However, these trajectories may differ in their intercepts and slope of change with age. We also expected that trajectory group membership would be related systematically to a variety of other indicators of cultural orientation (i.e., generation of immigration, ethnic pride, ethnic identity, perceived ethnic discrimination, biculturalism, and language use) in ways that make sense given the nature of the dual cultural adaptations occurring in each trajectory group. For example, the adolescents in trajectory groups that indicate a high endorsement (either initially or increasing over age) of Mexican American cultural values should score high in ethnic pride, ethnic identity, and Spanish language use. Adolescents in trajectory groups that are high in both Mexican American and mainstream cultural values should be high in these same culturally related variables and also be high in biculturalism and low in perceived discrimination. We also expected that the dual cultural adaptations represented by the distinct trajectory groups would not be highly consistent with the groups resulting from single-point-in-time median-split analyses.

Method

Participants

Data for this study come from the first, second, and third assessments (between 2004 and 2011) of an ongoing longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican American families (Roosa, Liu, Torres, Gonzales, Knight, & Saenz, 2008). Participants were 749 Mexican American adolescents (49% female) selected from the rosters of schools that served ethnically and linguistically diverse communities in the Phoenix metropolitan area. To recruit a representative sample of Mexican American families, a multiple step process was implemented that included: a stratified random sampling strategy to select neighborhoods diverse in cultural and economic qualities, recruitment through 47 schools across 35 neighborhoods, the use of culturally sensitive recruitment and data collection processes, conducting interviews in participants’ homes in English or in Spanish according to the participants’ preference, and a financial incentive (Roosa et al., 2008). We originally identified 237 potential communities for inclusion by identifying all public schools (including Catholic schools and Charter schools) in the metropolitan area with at least 20 Mexican American students in the fifth grade. We then scored the degree to which these communities provided support for parental enculturation efforts using multiple indicators (i.e., Mexican American population density, percentage of elected and appointed Latino office holders, the number of Churches holding service in Spanish, the number of locally owned stores selling traditional Latino foods/medications/household items, and the presence of traditional Mexican-style stores). We then selected the five communities that were scored as most “Mexican American” (because they represented Mexican ethnic enclaves). We ensured that we had represented the entire spectrum of community context by choosing a random starting point from within the 10 lowest scoring communities and then selecting every 9th school thereafter. A description of the breadth of these communities is provided in Roosa et al. (2008).

After receiving consent to contact families through a letter to the home, we attempted to contact 1,982 families. Of these, 12 (0.6%) families could not be contacted, 55 (2.8%) declined to participate before being screened, and 1,970 were screened to determine if they met the eligibility requirements. Of the 1,085 who met the eligibility requirements 749 (69.0%) completed the initial interview, 270 (24.9%) declined to participate, 4 (0.3%) began the interview but were unable to complete it, and 61 (5.6%) were not asked to participate because we had reached our recruitment goal. Of those who were ineligible: 56 (2.8%) no longer attended the participating school, 99 (5.0%) and 243 (12.3%) did not have a biological mother or father (respectively) in the home, 298 (15.1%) and 106 (5.4%) did not have a Mexican American biological mother or father (respectively), 16 (0.8) were severely learning disabled, 3 (.01%) could not speak either English or Spanish, and 9 (.04%) were participating in another research project. We included only families with both a Mexican American biological mother and father to limit the potential of another cultural influence within the home. Hence, the overall recruitment success was 73.2% of those who were eligible and asked to participate. This sample of Mexican American families was diverse with respect to both SES and language (Roosa et al., 2008). Family incomes ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $95,000, with the average family reporting an income of $30,000 – $35,000. In terms of language, 30.2% of mothers, 23.2% of fathers, and 82.5% of adolescents were interviewed in English. At Time 1, the mean age of mothers in our study was 35.9 (SD = 5.81) and mothers reported an average of 10.3 (SD = 3.67) years of education. At Time 2, the mean age of fathers was 38.1 (SD = 6.26) and fathers reported an average of 10.1 (SD = 3.94) years of education. The adolescents (48.7% female) ranged in age from 9 to 12 with a mean of 10.42 (SD = .55; with 97.6% being 10 or 11 years old) at Time 1. A majority of mothers and fathers were born in Mexico (74.3%, 79.9%, respectively), and a majority of adolescents were born in the United States (70.3 %).

At Time 2, approximately two years after Time 1 data collection, most students were in the 7th grade. Of the 39 (5.2%) families who did not participate at Time 2, 16 (2.1%) refused to participate. Families who participated at Time 2 were compared to families who did not participate at Time 2 on several demographic variables and no differences emerged among adolescent (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), mother (i.e., marital status, age, generational status), or father characteristics (i.e., age, generational status). At Time 3, approximately three years after Time 2 data collection, most students were in the 10th grade. Of the 109 (14.6%) families who did not participate at Time 3, 37 (4.9%) refused to participate. Families who participated at Time 3 were compared to families who did not participate at Time 3 on several demographic variables and no differences emerged among adolescent (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), mother (i.e., marital status, age, generational status), or father characteristics (i.e., age, generational status).

Procedure

Adolescents completed computer assisted personal interviews at their home, scheduled at the family’s convenience, that were about 2.5 hours long. The interviewers were: 80–90% female (depending upon the assessment year), between 23 and 60 years of age (with the exception of a 19 year old civil rights activist), fluent in both English and Spanish, recipients of a master’s or bachelor’s degree (or the combination of education and a least 2 years of professional experience in a social service agency), strong in communication and organizational skills, and knowledgeable about computers. Each interviewer received at least 40 hours of training that included information on the project’s goals, characteristics of the target population, the importance of professional conduct when visiting participants’ homes as well as throughout the process, and the critical role they would play in collecting the data. Interviewers read each survey question and possible responses aloud in participants’ preferred language to reduce problems related to variations in literacy levels. Participating adolescents were compensated $45 at Time 1, $50 Time 2, and $55 at Time 3.

Measures

Generation

Participants’ generation of immigration to the United States was determined based on their country of birth and the number of parents and grandparents that were born in Mexico. For example, a participant was coded as a first generation immigrant if they and their parents and grandparents were born in Mexico. A participant was coded as a second generation immigrant if they were born in the United States and their parents and grandparents were born in Mexico. A participant was coded as a third generation immigrant if they and their parents were born in the United States and their grandparents were born in Mexico. A participant was coded as a fourth generation immigrant (technically a fourth or beyond generation immigrant) if they, their parents, and their grandparents, were born in the United States. Participants whose background deviated slightly from these coding rules (i.e., when a grandparent was born in another Latin American country) were assigned the nearest appropriate code.

Mexican American and Mainstream Cultural Values

Adolescents completed the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS: Knight et al., 2010) to assess Mexican American values and mainstream values. The development of the MACVS was based on the values that Mexican American mother, father, and adolescent focus groups identified as associated with the Mexican American and mainstream American cultures. The Mexican American values scale consists of 5 correlated subscales from MACVS: Familism-Support (6 items, e.g., “parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”); Familism-Obligation (5 items, e.g., “if a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”); Familism-Referents (5 items, e.g., “a person should always think about their family when making important decisions”); Respect (8 items, e.g., “children should always be polite when speaking to any adult”); and Religiosity (7 items, e.g., “one’s belief in God gives inner strength and meaning to life”). The mainstream values scale consists of 3 substantially correlated subscales from the MACVS: Material Success (5 items, e.g., “the best way for a person to feel good about himself/herself is to have a lot of money”); Independence and Self-Reliance (5 items, e.g., “as children get older their parents should allow them to make their own decisions””); and Competition and Personal Achievement (4 items, e.g., “one must be ready to compete with others to get ahead”). Adolescents indicated their endorsement of each item by responding with a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) not at all to (5) very much. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the items for each subscale fit best on the respective subscale; that these subscales also loaded on these two higher order factors; and that there was reasonable measurement invariance between 5th grade adolescent and their mothers and fathers (Knight et al., 2010). Knight et al. (2010) also provide evidence of the validity of the MACVS subscale scores. The Cronbach’s α for the Mexican American values scale was .85, .90, and .92 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively. The Cronbach’s α for the mainstream values scale was .84, .84, and .81 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

Language Use

Adolescents completed the four English language use and four Spanish language use items from the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans-II (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995) at the first assessment. These items best represented the different contexts in which language use may be represented that assess both English (α = .69) and Spanish (α = .83) language use. The subset of language use items consists of an English use and Spanish use subscale. The subscales evaluate frequency of language use (e.g., “How often do you speak Spanish?”). The response scale ranged from 1 (almost never) to 5(almost always) and a mean score was computed for each language, with higher scores indicating greater language use.

Ethnic Pride

Adolescents completed the Mexican American Ethnic Pride Scale (Thayer, Valiente, Hageman, Delgado, and Updegraff, 2002) at the first assessment. The four-item scale (α = .78) assessed ethnic pride for in Mexican Americans (e.g., “You feel proud to see Latino actors, musicians, and artists being successful”). The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true) and a mean score was computed with higher scores indicating higher levels of ethnic pride.

Ethnic Identity

Adolescents completed the Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004) at the second assessment. The 17-item scale (α=.84) assessed ethnic exploration (e.g., “You have attended events that have helped you learn more about you ethnic background”), resolution (e.g., “You are clear about what your ethnic background means to you”), and affirmation (e.g., “You feel negatively about your ethnic background”; reverse coded). The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true) and an overall mean score was computed with higher scores indicating higher levels of ethnic identification.

Perceived Ethnic Discrimination

Adolescents completed nine items designed to assess discrimination experiences from peers and teachers at the first assessment. Because we were aware of no well-developed measures of perceived ethnic discrimination for use with Mexican Americans at the outset of the study, items were selected and adapted from three measures that had been validated for other groups [Hughes and Dodge (1997): Racism in the Workplace Scale; Landrine and Klonoff (1996): Schedule of Racist Events; and Klonoff and Landrine, (1995): Schedule of Sexist Events]. There were 4 peer items (e.g., “How often have kids at school called you names because you are Mexican American?”) and 5 teacher items (e.g., “How often have you had to work harder in school than White kids to get the same praise or the same grades from your teachers because you are Mexican American”) had a Cronbach’s α was.78. The response scale ranged from (1) Not at all true to (5) Very true and an overall mean score was computed with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived discrimination.

Biculturalism

Adolescents completed the Mexican-American Biculturalism Scale (Basilio et al., 2013) at the third assessment. This measure had been developed shortly before the beginning of the third assessment of the second cohort for this sample and was only available for this half of the sample. This measure has three subscales: Bicultural comfort (9 items), bicultural ease (9 items), and bicultural advantage (9 items), which represent the affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of biculturalism respectively. The response scale for bicultural comfort ranged from 1 (e.g., “I am only comfortable when I need to interact with other Mexican/Mexican-Americans” or “I am only comfortable when I need to interact with Whites (Gringos).”) to 5 (e.g., “I am always comfortable in both of these situations.”). The response scale for bicultural ease (e.g., “Needing to work with Mexicans/Mexican-Americans sometimes, and with Whites (Gringos) other times is”) ranged from 1 (very difficult) to 5 (very easy). The response scale for bicultural advantage (e.g., “For me, being able to interact with other Mexicans/Mexican-Americans sometimes, and being able to interact with Whites (Gringos) other times has”) ranged from 1 (many disadvantages) to 5 (many advantages). An overall mean biculturalism score was computed using the items from all three subscales (α = .88) with higher scores indicating higher levels of biculturalism.

Results

Data Analysis Plan

Even though we expected qualitatively different types of developmental trajectories we conducted preliminary longitudinal growth models (not presented here) separately, and jointly, for the trajectories of Mexican American cultural values and mainstream cultural values using Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) to confirm that there was indeed significant variability in the intercepts and slopes of the developmental trajectories. Based on the hypothesis of growth across school transitions, the time metric used in the longitudinal growth curve models was grade (grades 5, 7, and 10; approximately 11, 13, and 16 years of age). The standard deviations of participants age at each assessment was relatively small (SD = 0.55) indicating that using age would provide little or no information gain in growth curve modeling, but would entail much greater modeling demands. Furthermore, preliminary analyses revealed that using age and grade produced virtually identical log-likelihood estimates, parameter estimates, and estimated standard errors. Based on the evidence of significant variability in the intercepts and slopes of parallel process longitudinal growth curve modeling for the Mexican American cultural values and the mainstream cultural values, we conducted parallel latent class growth models centered at fifth grade (approximately 11 years of age). We examined latent class growth models for 1 to 5 classes, and examined the heterogeneity of residual variances across time and latent classes, and that of the intercept variance across latent classes , in order to minimize chances of over-extracting latent classes (Muthén, 2004 ) and producing biased results (Enders & Tofighi, 2008 ). To determine the optimal number of trajectory groups we relied on several criteria including: the Bayesian Information Criterion and the sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC and saBIC), the adjusted Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (LMR), all trajectory groups consisting of at least 5% of the sample; the probabilities of highest trajectory group membership being near .80, and the interpretability of the trajectories (Nylund , Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007).

After identifying the trajectory groups, we examined the association of these trajectory groups with several variables representing the ethnic adaptation of adolescents (adolescents English and Spanish use, ethnic pride, ethnic identity, perceptions of ethnic discrimination, and biculturalism) and adolescents’ gender and nativity. Preliminary analyses revealed that the trajectory groups differed on the intercepts of the trajectories of these culturally related variables that could change over time, but not the changes over time; so we examined the differences between the trajectory groups on these variables measured at the first assessment (with the exception of ethnic identity which was first measured at the second assessment and biculturalism which was first measured at the third assessment). To examine the relationship between the trajectory groups and each categorical variable (i.e., gender and generation) we conducted separate χ2 tests of association. To examine the relationship between the trajectory groups and each remaining continuous variable we conducted a series of one-way ANOVAs using the trajectory groups as the independent variable. Each significant omnibus F was followed by pairwise comparisons. Most of the missing data resulted from individual participants’ being unavailable after the initial data collection (represented by the noted retention rates) or the measure of biculturalism being administered to only half of the sample. Beyond this, less than 1% of participants had missing data for any variable included in this report at any assessment.

Finally, to compare our trajectory findings based upon latent class longitudinal growth curve modeling to the acculturation categorization approach used in earlier research, we compared the obtained trajectory groups to a median split classification (i.e., using those at or above the median versus those below the median) of the Mexican American cultural values and the mainstream cultural values at the first and third assessment. In addition, we compared the median split classification results at the first assessment with those at the third assessment.

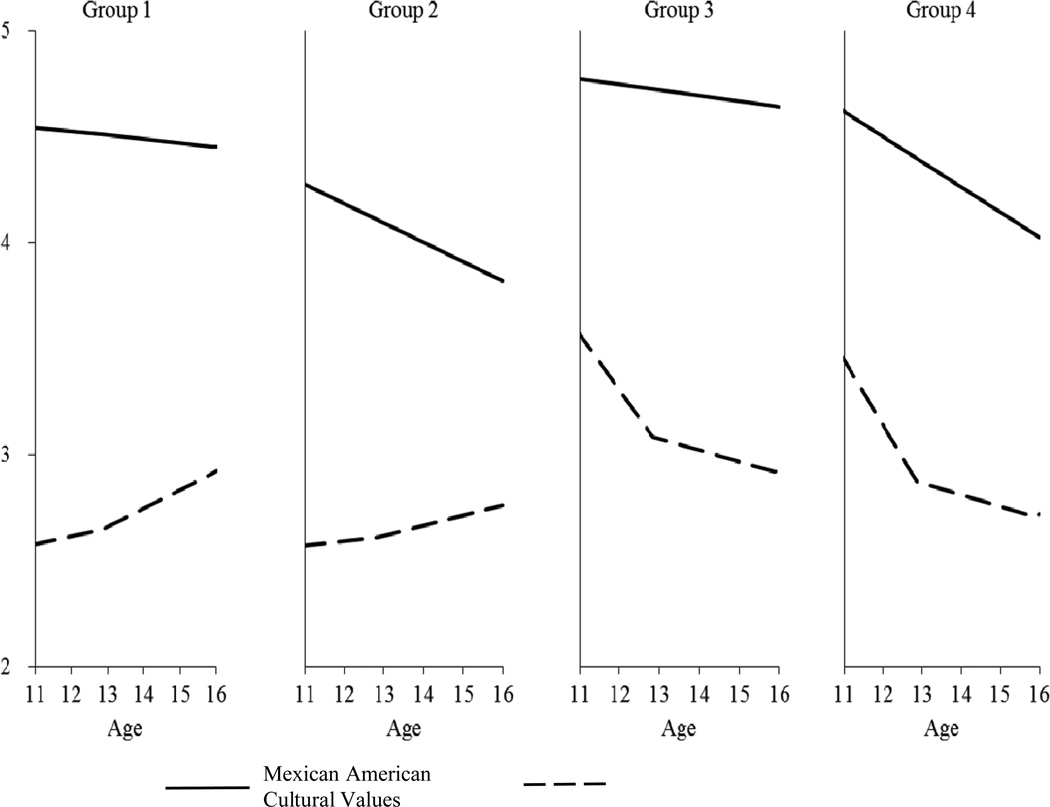

Parallel Latent Class Growth Models for Mexican American and Mainstream Values

Based on the fit criteria, we selected a four-class model in which the log-likelihood estimate = −2,473.54; the BIC = 5,211.83; the saBIC = 5,084.81; the adjusted LMR p = 0.17; the percentage of cases in each trajectory group ranged from 14.3% to 33.8%; and average probabilities of highest trajectory group membership ranged from 0.73 to 0.86 across the four groups. In addition, the average probability of any case being in a different trajectory group ranged from 0.00 to 0.13, indicating that the degree of classification error was not serious. The mean trajectories of the four classes for the Mexican American cultural values and the mainstream cultural values are displayed in Figure 1 with the intercepts and slopes for each class reported in Table 1. When the latent class growth model indicated the need for both a linear and quadratic slope but neither of the mean slopes was significant for a given class, we conducted a subsequent latent basis model (see Grimm, Ram, & Hamagami, 2011) to determine if there is a significant mean change over time (i.e., from the first to the third assessment) represented by the combined mean linear and quadratic slopes. The mean intercepts for all four trajectory groups were significantly greater than zero.

Figure 1.

The parallel process longitudinal trajectory groups for Mexican American and mainstream cultural values.

Table 1.

Intercepts, Slopes, and Standard Errors (in parentheses) of the Latent Class Longitudinal Trajectory Groups for Mexican American and Mainstream Cultural Values.

| Group | Parameter | Mexican American Cultural Values |

Mainstream Cultural Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 241) |

Intercept | 4.544 (0.038)** | 2.578 (0.069)** |

| Linear | −0.018 (0.014) | 0.017 (0.052) | |

| Quadratic | 0.010 (0.010) | ||

| Group 2 (n = 253) |

Intercept | 4.277 (0.031)** | 2.571 (0.059)** |

| Linear | −0.091 (0.013)** | 0.010 (0.049) | |

| Quadratic | 0.006 (0.008) | ||

| Group 3 (n = 107) |

Intercept | 4.776 (0.028)** | 3.560 (0.271)** |

| Linear | −0.027 (0.018) | −0.333 (0.102)** | |

| Quadratic | 0.041 (0.012)** | ||

| Group 4 (n = 148) |

Intercept | 4.618 (0.046)** | 3.437 (0.189)** |

| Linear | −0.119 (0.013)** | −0.399 (0.093)** | |

| Quadratic | 0.051 (0.013)** | ||

Note. Intercept centered at 11 years of age.

p < .05,

p < .01.

The first trajectory group (Group 1) includes 241 (32.2%) adolescents. These adolescents endorsed the Mexican American cultural values at a very high level and were relatively stable in the endorsement of these values over time. These adolescents also were moderate in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values (see Table 1). Neither the mean linear or quadratic slopes in-and-of –themselves indicated significant changes in mainstream cultural values over time; however, the latent basis model analyses indicated that this trajectory group on average did increase significantly (mean latent basis slope = 0.345, p < .001) from the first to the third assessment (see Figure 1). Although these adolescents endorse the Mexican American cultural values at very high levels and the mainstream cultural values at moderate levels, they appear to be increasingly accepting the mainstream cultural values more than any other trajectory group. Hence, these adolescents are high in Mexican American values and moderate but increasing in mainstream values and may be experiencing the demands of the dual cultural adaptation by becoming connected to both the ethnic and mainstream cultures.

The second trajectory group (Group 2) included 253 (33.8%) adolescents. These adolescents were initially the lowest, but still quite high, in the endorsement of Mexican American cultural values (i.e., their mean is 4.277 on a 5-point scale); but their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values declined over time. These adolescents were also moderate in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values (see Table 1). Again, although neither the mean linear or quadratic slopes were statistically significant, the subsequent latent basis model analyses indicated that this trajectory group on average did increase somewhat in mainstream cultural values (mean latent basis slope = 0.234, p < .001) from the first to the third assessment (see Figure 1). The adolescents in this trajectory group were becoming more similar in their level of endorsement of Mexican American and mainstream values over time; however, this is mostly because of their waning endorsement of Mexican American cultural values rather than their very modest increase in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values.

The third trajectory group (Group 3) included 107 (14.3%) adolescents. These adolescents were initially the highest in the endorsement of Mexican American cultural values, and this endorsement remained at a very high level over time. These adolescents were also initially moderately high in the endorsement of mainstream cultural values, but this endorsement declined considerably over time. However, the rate of decline in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values was also decreasing somewhat over time (see Figure 1). These adolescents are maintaining their high endorsement of the Mexican American cultural values, but over time their endorsement of the mainstream cultural values was waning. These adolescents were high in Mexican American Values and moderately high but declining in mainstream values. Hence, these adolescents may be experiencing the demands of the dual cultural adaptation by maintaining their connection to the ethnic culture while distancing themselves from the mainstream culture.

The fourth trajectory group (Group 4) included 148 (19.8%) adolescents. These adolescents initially endorsed the Mexican American cultural values at a very high level, but this endorsement declined considerably over time. This group was also initially moderately high in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values (i.e., 3.437 on a 5-point scale), but their endorsement declined considerably over time. However, the rate of decline in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values was also decreasing somewhat over time (see Figure 1). These adolescents were high in Mexican American values and moderately high in mainstream values but declining substantially in both set of values. Hence, these adolescents may be experiencing the demands of dual cultural adaptation by distancing themselves from both the Mexican American and the mainstream cultures. However, it is important to note that even after these substantial declines these adolescents were still endorsing Mexican American cultural values at moderately high levels and mainstream cultural values at moderate levels.

Relation of Trajectory Groups to Cultural Variables

Table 2 presents the relationships of the trajectory groups to the adolescent’s generational status. Compared to the adolescents in the third and fourth trajectory groups, the adolescents in the first trajectory group, and to some extent those in the second trajectory group, tend to more often have parents who were born in the United States (i.e., be 3rd and 4th generation immigrants). However, the generational differences across the four trajectory groups were quite small. Gender was not significantly associated with the trajectory groups [χ2 (3) = 3.43].

Table 2.

The percentage of each trajectory group by generation status.

| Trajectory Group |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 239) |

Group 2 (n = 252) |

Group 3 (n = 107) |

Group 4 (n = 148) |

χ2 (df) | ||

| Generation | First | 21.34% | 27.78% | 39.25% | 37.84% | χ2(9) =39.69*** |

| Second | 40.59% | 47.62% | 40.19% | 40.54% | ||

| Third | 16.74% | 5.56% | 4.68% | 10.81% | ||

| Fourth | 21.34% | 19.05% | 15.89% | 10.81% | ||

p < .001.

Only 746 out of 749 adolescents reported their generation status.

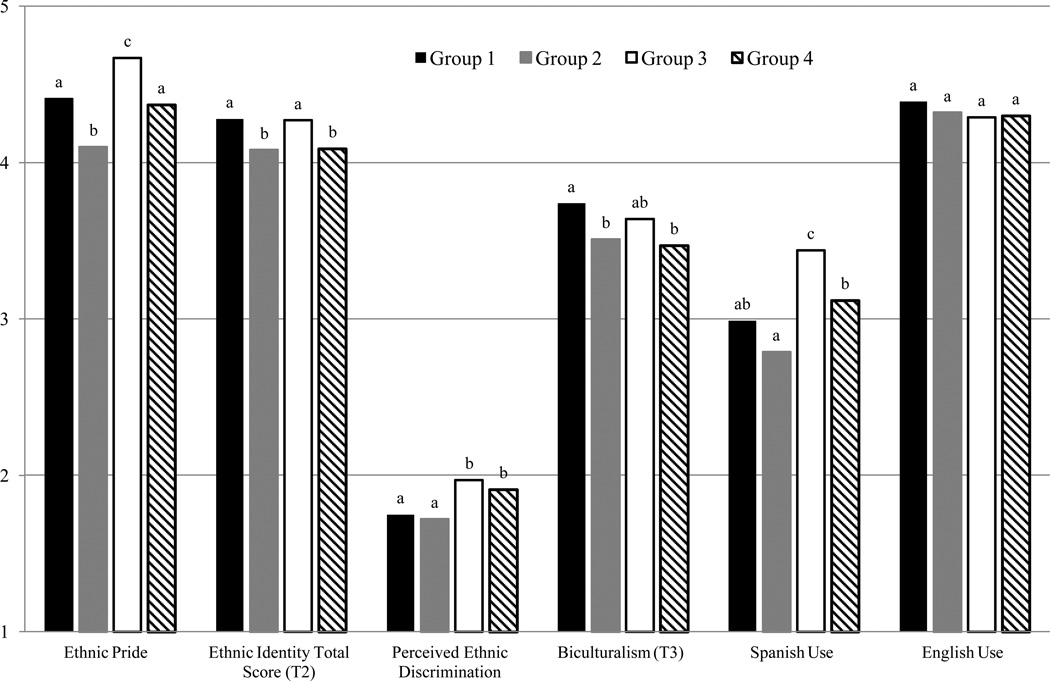

The series of one-way ANOVAs indicate that the four trajectory groups differed significantly in Ethnic Pride [F(3, 745) = 23.19, p < .001], Ethnic Identity [F(3, 706) = 9.96, p < .001], Perceived Ethnic Discrimination [F(3, 745) = 6.38, p < .001], Biculturalism [F(3, 301) = 4.71, p < .01], and Spanish Use [F(3, 745) = 12.25, p < .001], but not English Use [F(3, 745) = 0.96, ns]. The means of each culturally related variable for each trajectory group are presented in Figure 1. We performed all pairwise comparisons between the four trajectory groups using Tukey’s HSD test, and the superscripts above each bar indicate which groups differed significantly (p < .05) The trajectory groups that maintained their high endorsement of Mexican American cultural values over time but declined in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values (Group 3) were the highest in ethnic pride while the group declining in Mexican American cultural values and slightly increasing in mainstream cultural values (Group 2) was the lowest in ethnic pride. Trajectory Group 1 (high and stable Mexican American values and increasing in mainstream cultural values) and Group 4 (high but declining in Mexican American cultural values and declining in mainstream values) reported similar levels of ethnic pride and were between the other two groups. The two trajectory groups that maintained their high level of endorsement of Mexican American cultural values over time (Groups 1 and 3) were higher in ethnic identity than either of the two groups that were declining in their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values (Groups 2 and 4). The two trajectory groups that were increasing somewhat in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values over time (Groups 1 and 2) reported less perceived ethnic discrimination than either of the two groups that were declining in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values (Groups 3 and 4). Trajectory Group 1 (high and stable Mexican American values and increasing in mainstream cultural values) scored highest in biculturalism, and was significantly higher in biculturalism than either of the groups that were declining in their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values (Groups 2 and 4). Trajectory Group 3 (high and stable Mexican American values and decreasing in mainstream cultural values) was not significantly different from any of the other groups in biculturalism. Trajectory Group 3 (high and stable Mexican American values and decreasing in mainstream cultural values) also reported the most Spanish use compared to any of the other trajectory groups; while the two groups who were increasing somewhat in mainstream cultural values (Groups 1 and 2) were similarly lower in Spanish use. Finally, among the two trajectory groups who were declining in their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values (Groups 2 and 4), the group declining in mainstream cultural values (Group 4) reported higher Spanish use than the group increasing somewhat in mainstream cultural values (Group 2).

Relation among the Trajectory Groups and the Median Split Classifications

Table 3 presents the cross-tabulation of the observed trajectory groups with the median split classifications at the first and third assessment. Although the associations are statistically significant at each assessment (Time 1: χ2 (9) = 459.52, p < .001; Time 3: χ2 (9) = 345.61, p < .001), the patterns of associations are not compelling. For example, the Mexican American adolescents in the third and fourth trajectory group were most often classified as “bicultural” by the median split at the first assessment. However, the adolescents in these two trajectory groups were declining substantially in their endorsement of the mainstream cultural values as they got older. Those Mexican American adolescents who were maintaining a relatively high endorsement of Mexican American cultural values while increasingly endorsing mainstream cultural values as they got older (i.e., trajectory group 1) were least likely to be classified as “bicultural” by the median split procedure at the first assessment. Furthermore, the pattern of associations between the trajectory groups and the median split classifications based upon the third assessment of culturally related values were quite different from the associations observed with the first assessment. For example, by the third assessment the Mexican American adolescents in the fourth trajectory groups were no longer very likely to be classified as “bicultural;” and the adolescents in the first trajectory group were most likely to be classified as “bicultural.”

Table 3.

The percentage of each trajectory group by a single-point-in-time median split categorization at the first and the third assessment.

| Group 1 (n = 241) |

Group 2 (n = 253) |

Group 3 (n = 107) |

Group 4 (n = 148) |

χ2 (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1: | χ2(9) = 459.52*** | ||||

| Bicultural | 14.10% | 7.91% | 91.59% | 60.81% | |

| Assimilated | 18.68.% | 23.72% | 1.87% | 33.78% | |

| Separated | 38.59% | 15.02% | 5.61% | 3.38% | |

| Marginalized | 28.36% | 53.36% | 0.93% | 2.03% | |

| Time 3: | (n = 206) | (n = 218) | (n = 82) | (n = 131) | χ2(9) = 345.61*** |

| Bicultural | 52.43% | 7.80% | 56.10% | 10.69% | |

| Assimilated | 7.28% | 38.99% | 0.00% | 35.11% | |

| Separated | 35.44% | 6.42% | 43.90% | 15.27% | |

| Marginalized | 4.85% | 46.79% | 0.00% | 38.93% | |

p < .001.

Table 4 presents the cross-tabulation of the observed median split classifications at the first and third assessment. Although the associations are statistically significant (χ2 (9) = 56.47, p < .001) the patterns of associations are not consistently compelling. Only 36.73% of the Mexican American adolescents were classified into the same dual cultural adaptation group by the median split classification at the first and third assessment. Furthermore, some of the inconsistent classifications are difficult to explain. For example, 22.47% of those adolescents classified as “marginalized” at the first assessment were classified as “bicultural” at the third assessment.

Table 4.

The percentage of Mexican American adolescents categorized by a median split at the first assessment compared to the median split categorization at the third assessment.

| Time 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicultural | Assimilated | Separated | Marginalized | χ2 (df) | |

| Time 3 | χ2(9) = 56.47*** | ||||

| Bicultural | 37.25% | 30.47% | 23.62% | 22.47% | |

| Assimilated | 20.10.% | 33.59% | 15.75% | 23.60% | |

| Separated | 24.02% | 11.72% | 38.58% | 16.85% | |

| Marginalized | 18.63% | 24.22% | 22.05% | 37.08% | |

p < .001

Discussion

A number of authors have suggested that exposure to the ethnic and mainstream cultures will lead to changes in a variety of features of cultural orientation over time (e.g., Berry, 2006; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Félix-Ortiz, Newcomb, & Myers, 1994; Gonzales et al., 2002; LaFramboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993; Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, & Wong, 2002) that may create risk factors for, or protective factors against, negative health and other life outcomes (e.g., Atzaba-Poria & Pike, 2007; Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006; Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993; Vega & Gil, 1999). Hence the present study was designed to identify groups of Mexican American youth demonstrating distinct trajectories of change in Mexican American and mainstream cultural values across a seven year developmental time frame. To help gauge the validity of the resulting trajectory groups, this study was also designed to examine the relationship between these trajectory groups and several other indicators of cultural orientation. Finally, to evaluate the utility of the longitudinal approach to identify trajectories of change in cultural values over time we examined the relationship of these trajectory groups to the groups identified through the median split of a single-point-in-time assessment.

The parallel process latent class longitudinal growth curve modeling revealed four groups of individuals experiencing different longitudinal trajectories of change in Mexican American and mainstream cultural values. Importantly, all four trajectory groups were initially quite high in their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values, indicating these value dimensions are broadly relevant and prevalent in the families and communities of our diverse sample of Mexican American youth. However, these groups were distinguished by the extent to which their levels of endorsement of Mexican American values declined over time from late childhood to mid-adolescence, and also based on changes over time in adolescents’ endorsement of mainstream cultural values. The adolescents in the first two trajectory groups (Groups 1 and 2) showed a similar pattern of moderate but increasing endorsement of mainstream cultural values that distinguished them from two other groups that decreased in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values over time (Groups 3 and 4). However, whereas the first trajectory group maintained their high endorsement of Mexican American values, the second group showed significant declines in Mexican American values over time. From a person centered perspective, the first group also showed a pattern of scores on culturally related variables that reflected their strong connection to the ethnic culture with increasing connection to the mainstream culture: . The adolescents in this group were high in ethnic pride, ethnic identity, biculturalism, and English use; they used Spanish moderately often and perceived relatively little ethnic discrimination. In contrast, adolescents in the second trajectory group were lower in ethnic pride, ethnic identity, and biculturalism relative to the first trajectory group. Adolescents in the third and fourth trajectory groups showed a similar pattern of moderate but decreasing endorsement of mainstream values over time that contrasted with the first two groups. However, contrasted with each other, adolescents in the third group maintained higher levels of endorsement of Mexican American values over time compared to the fourth group. These adolescents were relatively high in ethnic pride, ethnic identity, biculturalism, and both Spanish and English use. But, they also perceived a bit more discrimination than the adolescents in the first two groups, potentially explaining their relative decline in endorsement of mainstream values over time. Adolescents in the fourth trajectory group declined significantly over time from initially high levels of Mexican American values and also reported lower levels of ethnic pride, ethnic identity, and Spanish language use relative to adolescents in the third group. Furthermore the adolescents in these two trajectory groups with declining mainstream values were somewhat higher in ethnic pride and perceived discrimination and used Spanish somewhat more often than the first two groups with increasing endorsement of mainstream values over time.

Although, these trajectory groups were associated with a variety of culturally related variables in ways that support the validity of these groups, differences between the trajectory groups were very modest in size. These differences were modest, in part, because the Mexican American and mainstream cultural values and the culturally related variables used for validity comparisons were substantially skewed. Hence, although the Mexican American cultural values, the ethnic pride, ethnic identity, biculturalism, and language use measures relied on a four- or five-point response scale almost no participants utilized the lowest response option and relatively few utilized the second lowest response option. Interestingly, the perceived discrimination scores were skewed positively with relatively few participants reporting very high perceived ethnic discrimination.

While the nature of the relationships between the observed trajectory groups and the culturally related variables supports the validity of the trajectory findings, the nature of these trajectory groups is not completely consistent with the groups identified in the studies that have assessed the dual cultural adaptations of individuals in single-point-in-time assessments using median or mid-scale splits (e.g., Berry, 2007; Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, 1980). The adolescents in each of the trajectory groups endorse Mexican American cultural values at relatively high levels, even though there are differences among the groups in the maintenance of these values. Hence, it is difficult to characterize any of these participants as “assimilated” or “marginalized.” The strong endorsement of Mexican American cultural values might well be expected given the relatively extensive Mexican American cultural experiences associated with growing up in Mexican American families. Although one might think that the adolescents who are maintaining their Mexican American cultural values and declining in their endorsement of the mainstream cultural values (i.e., those in trajectory group 3) could be characterized as “separated,” it is important to note that, although their endorsement of these values is declining with age, at sixteen they are still at comparable levels to those in the groups who are increasing in these values. Similarly, although the adolescents who are stable and high in Mexican American cultural values and increasing in mainstream cultural values with age (i.e., those in trajectory group 1) may be conceptually close to the definition of “bicultural”, at sixteen years of age these adolescents are endorsing mainstream cultural values at about the same level as the adolescents in trajectory group 3 who are similar in the maintenance of Mexican American cultural values but declining in mainstream cultural values.

The distinctions between these four trajectory group types of dual cultural adaptations are based primarily on the adolescents’ longitudinal changes in their endorsement of Mexican American and mainstream cultural values rather than their absolute levels of endorsement of these values. This is consistent with the perspective that adolescence is a developmental period during which such culturally related values are internalized at least in part because this internalization may be dependent upon elements of ethnic identity development (e.g., Armenta, Knight, Carlo, & Jacobson, 2011). That is, before one adopts the values of an ethnic group, there likely must be some affirmation of belonging to that group and some exploration of the nature of that group. Although this ethnic identity affirmation and ethnic identity exploration may have begun at a younger age, adolescence is the developmental period during which these features of ethnic identity become particularly salient (e.g., Phinney, 1990; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009).

That these four types of dual cultural adaptation are primarily based on longitudinal changes also has important methodological and analytical implication. A single-point-in-time assessment could not detect these types of dual cultural adaptations. Nor could a static analytical approach (i.e., a median split, mid-scale split, or even a latent class analysis) detect these types of adaptations. Clearly, longitudinal assessments and person-centered analytical procedures that examine individuals’ changes over time are essential for examining the dual cultural adaptations of psychological and behavioral variables that are undergoing substantial developmental change or environmental impact that produces change. There may be some variables for which a single assessment and more static analytical approach might reveal dual cultural adaptation types similar to those identified in a more longitudinal approach. For example, Knight et al. (2009) found two trajectories of ethnic affiliation (i.e., one group that affiliated mostly with other Mexican Americans and one group that affiliated more equally with Mexican Americans and Anglo Americans) that were relatively stable from14 to 20 years of age. Although a latent class analysis at any one assessment would likely have detected these same two groups, a median split or mid-scale split probably would not reveal the same types of dual cultural adaptations. Furthermore, a latent class analysis and single-point-in-time assessment likely would not reveal the same two underlying types of dual cultural adaptation if one’s sample included a substantial number of recent immigrants whose affiliation patterns may be changing based upon their changing life experiences. Given the development of analytical procedures designed to identify longitudinal changes at the individual level, and the identification of groups of individuals experiencing similar types of individual change, it is time for the study of acculturation and enculturation as processes of adaptation to a dual cultural existence to move beyond the single point in time assessment and median or mid-scale split approach.

Although the present developmental trajectory group classifications are significantly related to the median split classifications at both the first (i.e., fifth grade, approximately 11 years of age) and third assessment (i.e., tenth grade, approximately 16 years of age), the nature of these classification agreements suggests that these two different types of classification procedures are identifying essentially different clusters of Mexican American adolescents. For example, the adolescents who are maintaining their high endorsement of Mexican American cultural values as they are increasingly endorsing mainstream cultural values (i.e., those in trajectory group 1) are least likely to be classified as bicultural at the first assessment using the median split procedure. In contrast, these same adolescents are most likely to be classified as bicultural at the third assessment using the median split procedure. Similarly, the adolescents whose endorsement of both the Mexican American and mainstream cultural values are declining substantially over time (i.e., those in trajectory group 4) are most likely to be classified as bicultural by the median split procedure at the first assessment, but most likely to be classified as marginalized or assimilated by the median split procedure at the third assessment. Hence, these two procedures for identifying the type of dual cultural adaptation these Mexican American adolescents are experiencing are not consistent. Furthermore, although there is significant agreement between the medial split classifications at the first and third assessments, this association is weak, and over 63% of the Mexican American adolescents were in different median split categories at the two assessments. Approximately one of every five adolescents classified as bicultural at one of the two assessments were classified as marginalized at the other assessment even though these are the theoretically most distinct types of dual cultural adaptation.

The implications are clear. In addition to the problems associated with the use of the median split procedure with arbitrary cut-points (e.g., DeCosta, Iselin, & Gallucci, 2009; MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002), this procedure cannot be used to evaluate the nature of the dual cultural adaptation of ethnic minority individuals on indices of cultural adaptation that are changing over time due to some normative developmental processes or changing experiential processes. One may suspect that the present limitations of the median-split findings are a sample/variable specific problem associated with the skewedness of the scores on the culturally related variables. However, such a skewed distribution of scores has been shown to be relatively common among measure of culturally related constructs in measures of acculturation, ethnic identity, ethnic pride, ethnically associated stress, and perceived discrimination (e.g., Coatsworth et al., 2005; Knight et al., 2009). Hence, the median split procedure is not optimal for examining the acculturation and enculturation of ethnic/mainstream identities, the internalization of culturally related values, or the formation of relatively complex attitudes and behavior patterns among ethnic minority youths at certain ages because these features of cultural orientation undergo developmental changes across a relatively broad age-span. This is not to say that the more traditional median-split procedure is always inappropriate. The median split procedure may be useful for characterizing the acculturation/enculturation outcomes of relatively simple behaviors that are generally stable after a relatively young age and that are relatively normally distributed. For example, there is relatively little change in language use (i.e., Spanish and English use) patterns among Mexican American youth after early to mid-adolescence (Knight et al, 2009). Hence, the median-type split procedure could be useful for characterizing the dual cultural adaptation, indexed by language use, of Mexican American adults, assuming one uses a more nuanced and valid cut-point (e.g., Coatsworth et al., 2005) rather than the arbitrary and sample specific median. Even here, though, this type of classification could be compromised if the sample were to include a substantial number of recent immigrant adults who are in the process of improving their English capabilities and increasingly being exposed to situations in which they use the English language.

In summary, the present study identified four groups of Mexican American adolescents that are demonstrating distinct patterns of developmental changes in their endorsement of Mexican American and mainstream cultural values that reflect the adaptations associated with growing up in a dual cultural context. All of these adolescents were relatively high in their endorsement of Mexican American cultural values, and even those adolescents in the two trajectory groups that declined substantially in Mexican American cultural values remained relatively high in their endorsement of these values. All of these adolescents were more moderate in their endorsement of mainstream cultural values and some demonstrated modest increases with age while others demonstrated substantial decreases with age. Hence, these trajectory groups do not conform to those characterized by the common four-fold typology of dual cultural adaptations based upon median splits of single-point-in-time assessments (e.g., Berry, 2007; Szapcoznik et al., 1980). Further, the adolescents in these trajectory groups differ in a number of culturally related variables (i.e., generation of immigration, English and Spanish language use, ethnic pride, ethnic identity, perceived discrimination, and biculturalism) in ways that make conceptual sense. Hence, the present study demonstrates the utility of modern latent class longitudinal growth modeling as a means of assessing the outcomes associated with the processes of acculturation and enculturation for psychological constructs that may be undergoing developmental changes (e.g., the internalization of values) or changes associated with life experience experiences (e.g., immigration). Although this method of characterizing the process of change in cultural orientation during a critical stage of development may be important for advancing the field, future research is needed to evaluate how these changes relate to other aspects of development (i.e., academic success, mental and physical health, and well-being, etc.) that are important for advancing theory and culturally relevant services and policy.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of each trajectory group on each culturally related variable.

Groups with a differnt superscript differ significantly (p ≤.05).]

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by NIMH grant MH68920 (Culture, Context, and Mexican American Mental Health). The authors are thankful for the support of Mark W. Roosa, Jenn-Yun Tein, Marisela Torres, Jaimee Virgo, our Community Advisory Board and interviewers, and the families who participated in the study.

References

- Altschul I, Oyserman D, Bybee D. Racial-ethnic identity in mid-adolescence: Content and change as predictors of academic achievement. Child Development. 2006;77:1155–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends-Tόth J, van de Vijver FJR. Assessment of psychological acculturation. In: David S, Berry JW, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Knight GP, Carlo G, Jacobson RP. The relation between ethnic group attachment and prosocial tendencies: The mediating role of cultural values. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;41:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Atzaba-Poria N, Pike A. Are ethnic minority adolescents at risk for problem behavior? Acculturation and intergenerational acculturation discrepancies in early adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2007;25:527–541. [Google Scholar]

- Basilio C, Knight GP, O’Donnell M, Roosa M, Gonzales NA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Torres M. The Mexican American Biculturalism Scale: Bicultural Comfort, Ease, and Advantage for Adolescents and Adults. Manuscript under review. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0035951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: A conceptual overview. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2006. pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation strategies and adaptation. In: Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Bornstein MH, editors. Immigrant Families in Contemporary Society. Duke Series in Child Development and Public Policy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB. Peer groups and peer cultures. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:157–174. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel E, Schiefer D, Möllering A, Benish-Weisman M, Boehnke K, Knafo A. Value differentiation in adolescence: The role of age and culture. Child Development. 2012;83:322–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCosta J, Iselin A-MR, Gallucci M. A conceptual and empirical examination of justifications for dichotomization. Psychological Methods. 2009;14:349–366. doi: 10.1037/a0016956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Miller PA, Shell R, McNalley S, Shea C. Prosocial development in adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:849–857. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. The impact of misspecifying class-specific residual variances in growth mixture models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2008;15:75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz M, Newcomb MD, Myers H. A multidimensional scale of cultural identity for Latino and Latina adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1994;16:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez A, Saenz D, Sirolli AA. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States: Current Research and Future Directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Ram N, Hamagami F. Nonlinear growth curves in developmental research. Child Development. 2011;82:1357–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Dodge MA. African American women in the workplace: Relationships between job conditions, racial bias at work, and perceived job quality. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:581–599. doi: 10.1023/a:1024630816168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Witkow MR, Baldelomar OA, Fuligni AJ. Changes in ethnic identity across the high school years among adolescents with Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:683–693. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff EA, Landrine H. The Schedule of Sexist Events: A measure of lifetime and recent sexist discrimination in women's lives. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:439–472. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettkal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds D, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Losoya SH, Cho YI, Chassin L, Williams JL, Cota-Robles S. Ethnic identity and offending trajectories among Mexican American juvenile offenders: Gang membership and psychosocial maturity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Vargas-Chanes D, Losoya SH, Cota-Robles S, Chassin L, Lee JM. Acculturation and enculturation trajectories among Mexican American adolescent offenders. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:625–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFramboise T, Coleman HLK, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus (Version 6.00) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Lee S. Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:311–342. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77:1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Cortes DE, Malgady RG. Acculturation and mental health among Hispanics. American Psychologist. 1991;46:585–597. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Liu F, Torres M, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Saenz DS. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego RY, Gonzalez NA. Multiple mediators of the effects of acculturation status on delinquency for Mexican American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:189–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1022883601126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Des Rosier S, Huang S, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Knight GP, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12047. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, Briones E. The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development. 2006;49:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH. A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology. 1999;48:23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Azmitia M. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:601–624. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines W, Fernandez T. Biculturalism and adjustment among Hispanic youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1980;4:353–375. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM. Family psychology and cultural diversity: Opportunities for theory, research and application. American Psychologist. 1993;48:400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tadmor CT, Tetlock PE. Biculturalism: A model of the effects of second-culture exposure on acculturation and integrative complexity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SM, Valiente C, Hageman D, Delgado M, Updegraff KA. Conflict resolution in friendships: A comparison of Mexican American and Anglo American adolescents; Paper presented at the poster presented at National Council of Family Relations; Houston, TX. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]