Abstract

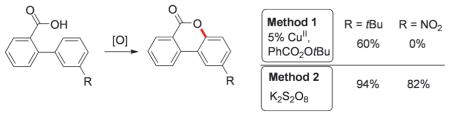

Two methods for remote aromatic C–H oxygenation reaction have been developed. Method 1, the Cu-catalyzed oxygenation reaction is highly efficient for cyclization of electron-neutral and electron-rich biaryl carboxylic acids into 3,4-benzocoumarins. Method 2, the K2S2O8-mediated oxygenation reaction, is more general and practical for cyclization of substrates with electron- donating and -withdrawing groups (see scheme).

Keywords: benzocoumarins, carboxylic acids, C–H activation, oxygenation, radical reactions

Transition-metal-catalyzed aromatic C–H oxygenation reaction[1] is a very powerful tool for straightforward synthesis of valuable oxygen-containing products from abundant arenes.[2] Of these reactions, intramolecular C–H/O–H oxidative coupling of carboxylic acid with unactivated sp2 C–H bond is an important transformation, because it gives an access to a variety of valuable lactone-containing molecules.[3] Thus, 3,4-benzocoumarin fragment 2, containing six-membered lactone moiety, is widely found in natural and bioactive molecules, as well as in useful materials.[4] Expectedly, 2 can be accessed through cyclization of nonpre-functionalized 2-arylbenzoic acids 1; however, the existing methods require either employment of stoichiometric amounts of toxic oxidants[5] or UV irradiation,[6] which substantially limits applicability of these methods (Scheme 1). We hypothesized that it should be possible to develop a general, practical, and environmentally benign dehydrogenative C–H/O–H lactonization reaction of 2-arylbenzoic acids 1 into 3,4-benzocoumarins 2 en route to oxygenated biaryls 3. We envisioned that C–H oxygenation could potentially be performed by formation of carboxyl O-centered radical A, which would undergo a subsequent C–O bond formation.[7]

Scheme 1.

Carboxyl-group-directed C–H oxygenation reactions.

Herein, we report two complimentary methods for this transformation. Method 1, the Cu-catalyzed oxygenation reaction of 2-arylbenzoic acids, which is efficient for electron-neutral and electron-rich substrates. During preparation of this manuscript, a similar to Method 1 Cu-catalyzed transformation was disclosed by Gallardo-Donaire and Martin.[8] Most importantly, we also developed a more general and practical Method 2, the K2S2O8-mediated oxygenation reaction, which is widely applicable for cyclization of electron-neutral, electron-rich, as well as electron-deficient substrates.

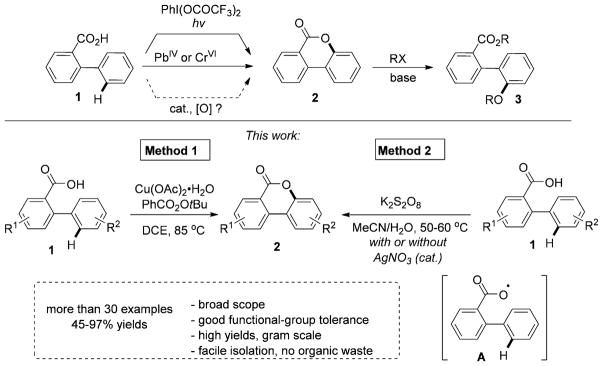

To develop mild and environmentally benign intramolecular lactonization reaction of 2-arylbenzoic acids, we performed extensive screening of transition-metal catalysts and oxidants.[9] It was found that this reaction can efficiently be accomplished by using CuII catalyst. Thus, 2-phenylbenzoic acid 1a was converted into the desired benzocoumarin product 2a in 88% yield in the presence of Cu(OAc)2·H2O (5 mol%) and tert-butyl peroxybenzoate (TBPB, Luperox P) in dichloroethane (Method 1). We found that substrates with electron-neutral and electron-donating substituents, as well as aryl halide fragments (Hal=F, Cl, Br) and cyanogroup on the “guest” aryl ring, produced the desired products in good to excellent yield (Table 1, entries 2a–j). In general, benzoic acids substituted with arene ring containing meta-substituents (F, Cl, OMe, tBu) preferentially underwent cyclization at the less hindered site (Table 1, entries 2k–n). In contrast, meta-Me substituted substrate 1o cyclized at the more hindered site producing 2o as a major regioisomer (4:1).[10] In addition, 2-naphthyl substituted benzoic acid 1p gave the product of cyclization at the more electron-rich 1-position, exclusively (2p). Likewise, substrates containing 3,5-disubstituted arene ring also underwent efficient cyclization into benzocoumarin products 2q and r. 2-Phenylbenzoic acids containing substituents at 1-, 2-, and 3-positions also underwent smooth C–H oxygenation reaction producing products 2s–v. Although electron-neutral and electron-rich substrates under these reaction conditions (Method 1) gave the corresponding benzocoumarins in good to excellent yields, cyclization reaction of electron-deficient substrates was less efficient. Hence, 2-arylbenzoic acids with important electron-withdrawing functional groups, such as CF3 (1w), COMe (1x), and CONMe2 (1y) provided the corresponding products in diminished yields, whereas substrates possessing CHO (1z), CF3 (1aa, ab), and NO2 groups (1ac–ae) produced trace to no product at all (Table 1).

Table 1.

CuII-catalyzed C–H oxygenation reaction.

|

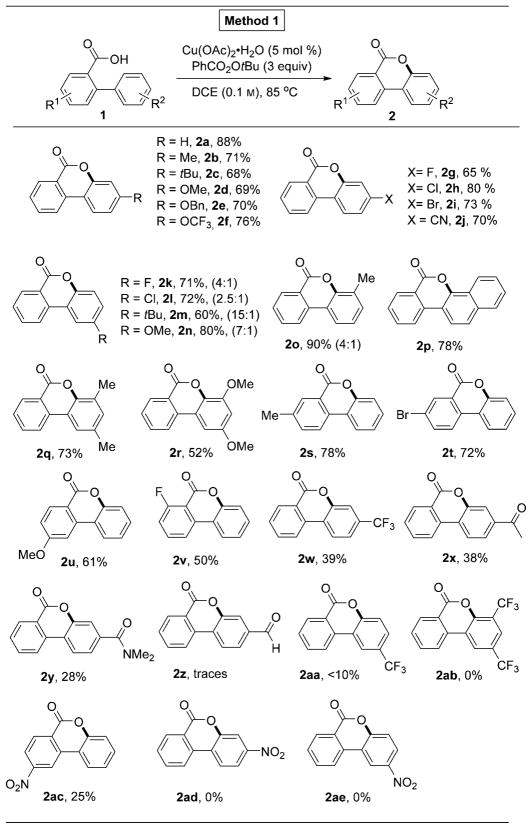

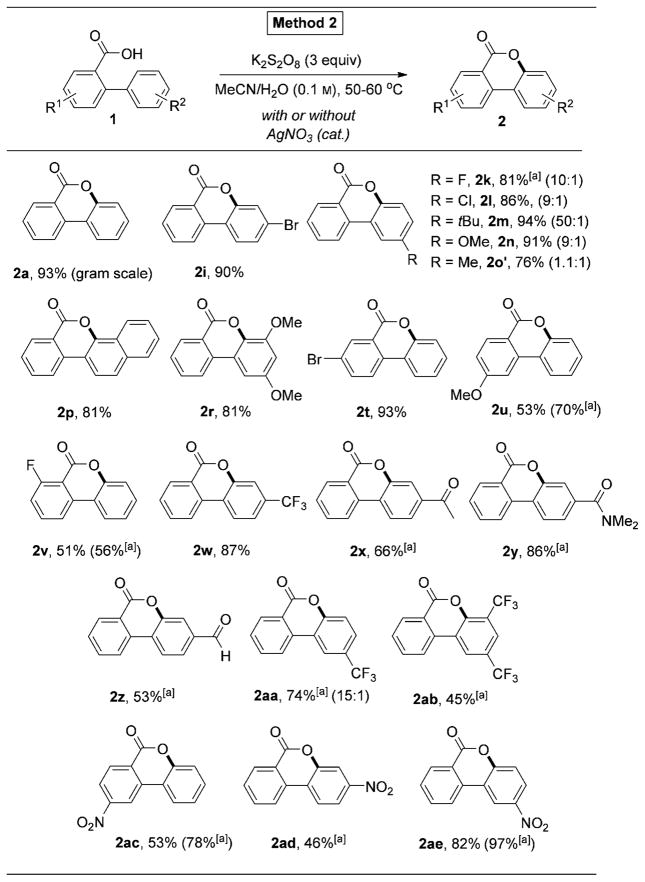

To overcome this limitation of the Cu-catalyzed oxygenation reaction (Method 1, Table 1), we aimed at the development of a complementary method for cyclization of electron deficient 2-arylbenzoic acids. Delightfully, we found that this transformation can be performed in the presence of K2S2O8 oxidant in aqueous acetonitrile.[11] Thus, benzocoumarin 2a was formed in 93% yield from 2-phenylbenzoic acid 1a in gram-scale manner by using this convenient and environmentally benign protocol (Table 2). We found that Method 2 works efficiently for electron-neutral and electron-deficient substrates under these conditions (entries 2a, i,p, r, t,u). Notably, in the presence of K2S2O8, benzoic acids substituted with arene ring containing meta-substituents produced the corresponding products in higher selectivity compared to that of Method 1 (Table 2, entries 2k–o′). Most importantly, the developed protocol can be successfully applied to a variety of electron-deficient substrates. Accordingly, 2-arylbenzoic acids with CF3 (2w, 2aa), COMe (2x), CONMe2 (2y), and CHO (2z) groups underwent cyclization producing the corresponding products in good to excellent yields. Moreover, previously incompetent substrates with highly electron- withdrawing NO2 group (2ac, 2ad, 2ae) and even two CF3 groups (2ab) now were smoothly transformed into the corresponding benzocoumarin products (Method 1, Table 1). It should be mentioned that in some cases, addition of a catalytic amount of AgNO3 (10 mol%) led to substantial increases of reaction rates.[12, 13]

Table 2.

K2S2O8-mediated C–H oxygenation reaction.

|

AgNO3 (10 mol%) additive was used.

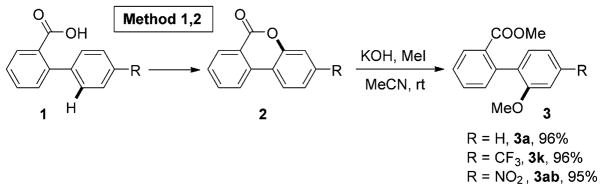

Naturally, the developed methods open access to a variety of densely functionalized benzocoumarin molecules.[4] In addition, considering the importance of aryl ether moiety, we have shown that the obtained 3,4-benzocoumarins could be nearly quantitatively converted into the corresponding biaryl ethers 3 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Conversion of lactones into aryl ethers.

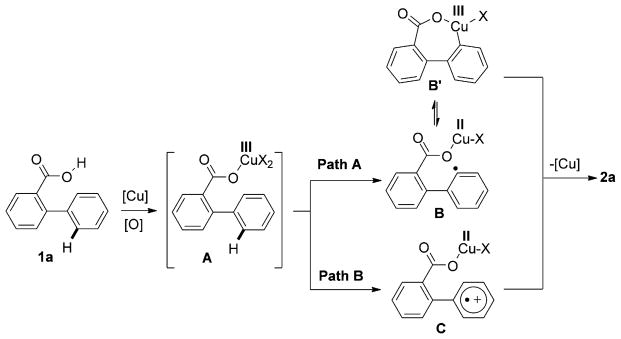

It is likely that the CuII-catalyzed oxygenation reaction (Method 1) proceeds through an active CuIII intermediate A (Scheme 3), which may abstract the adjacent hydrogen atom to form aryl radical B (Path A). The latter, upon oxidative ring closure, would produce B′, followed by a reductive elimination to form 2.[14, 15] Alternatively, a single-electron transfer (SET) process in A would give radical–cation specie C (Path B), which would be transformed into 2 by a subsequent C–O bond-forming reaction.[16]

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for Method 1.

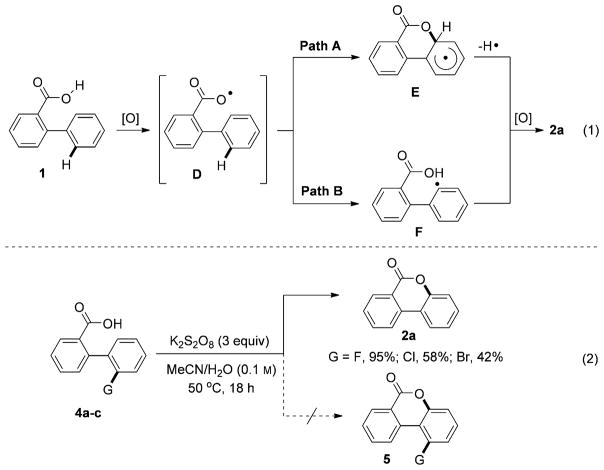

The K2S2O8-mediated oxygenation reaction (Method 2) most likely proceeds by oxidation of benzoic acid 1 into an O-centered carboxylic radical D, which undergoes addition to the arene ring to form an aryl radical intermediate E (Scheme 4, [Eq. (1)], Path A). The latter converts into the benzocoumarin product 2a upon loss of a hydrogen radical. This homolytic aromatic substitution mechanism is supported by our experiments on cyclization of substrates containing 2-haloaryl substituents 4a–c (G= F, Cl, Br). It was found that these reactions exclusively produce substitution products 2a instead of possible C–H coupling products 5 (Scheme 4, [Eq. (2)]).[17] Alternative mechanism involving an abstraction of hydrogen radical from the aromatic ring in the intermediate D to form the aromatic radical F cannot be ruled out at this stage (Scheme 4, [Eq. (1)], Path B).

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism for Method 2.

In conclusion, two complimentary methods for carboxyl-group- directed remote C–H oxygenation reaction of arenes were developed. Method 1, the Cu-catalyzed reaction, produces a variety of 3,4-benzocoumarins containing electron-neutral and electron-releasing substituents. In addition, a more general Method 2, the K2S2O8-mediated transformation, which is widely applicable to various electron-rich and electron-deficient 2-arylbenzoic acids, was developed. This protocol features a broad scope, a good functional group tolerance, and good selectivity. It is also benign, operationally simple, easily scalable, and proceeds under mild conditions.

Experimental Section

Procedure for oxygenation of 2-phenylbenzoic acid

Under ambient atmosphere, 2-phenylbenzoic acid 1a (1.98 g, 10 mmol) and K2S2O8 (8.2 g, 30 mmol, 3 equiv) were added to a round-bottom flask (250 mL) equipped with stirring bar, followed by addition of H2O/MeCN (100 mL, 1:1) mixture. The resulting reaction mixture was heated for 18 h at 50°C by using oil bath (GC monitoring). After reaction was complete, an aqueous solution of NaOH (50 mL, 1M) was added to the reaction mixture at RT. The product was extracted with ethyl acetate (3×30 mL), the combined organic extract was dried (Na2SO4), filtered (short path of silica gel), and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The product 2a was obtained in 93% yield (1.82 g) as a white solid.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The support of the National Institute of Health (GM-64444) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1112055) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201303511.

References

- 1.For general reviews on transition-metal-catalyzed C–H activation reactions, see: Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. Nat Chem. 2013;15:369. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1607.Kuhl N, Hopkinson MN, Wencel-Delord J, Glorius F. Angew Chem. 2012;124:10382. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203269.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:10236.Enthaler S, Company A. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4912. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15085e.Xu LM, Li BJ, Yang Z, Shi ZJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:712. doi: 10.1039/b809912j.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e.Gulevich AV, Gevorgyan VG. Chem Heterocycl Compd. 2012;48:1720.Alonso DA, Nájera C, Pastor IM, Yus M. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:5274. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000470.Yu J-Q, Shi Z-J, editors. Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol 292: C–H Activation. Springer; Berlin: 2010.

- 2.For selected example of transition-metal-catalyzed C–H oxygenation of arenes, see: Dick AR, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2300. doi: 10.1021/ja031543m.Dick AR, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12790. doi: 10.1021/ja0541940.Emmert MH, Cook AK, Xie YJ, Sanford MS. Angew Chem. 2011;123:9680. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103327.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9409.Chen X, Hao XS, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6790. doi: 10.1021/ja061715q.Zhang YH, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14654. doi: 10.1021/ja907198n.Wang X, Lu Y, Dai HD, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12203. doi: 10.1021/ja105366u.Gu S, Chen C, Chen W. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7203. doi: 10.1021/jo901316b.Gou FR, Wang XC, Huo PF, Bi HP, Guan ZH, Liang YM. Org Lett. 2009;11:5726. doi: 10.1021/ol902497k.Chernyak N, Dudnik AS, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8270. doi: 10.1021/ja1033167.Huang C, Ghavtadze N, Chattopadhyay B, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17630. doi: 10.1021/ja208572v.Lubriks D, Sokolovs I, Suna E. Org Lett. 2011;13:4324. doi: 10.1021/ol201665c.Huang C, Ghavtadze N, Godoi B, Gevorgyan V. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:9789. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201616.Sun P, Li W. J Org Chem. 2012;77:8362. doi: 10.1021/jo301384r.Gulevich AV, Melkonyan FS, Sarkar D, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5528. doi: 10.1021/ja3010545.Li W, Sun P. J Org Chem. 2012;77:8362. doi: 10.1021/jo301384r.Thirunavukkarasu VS, Ackermann L. Org Lett. 2012;14:6206. doi: 10.1021/ol302956s.Yang F, Ackermann L. Org Lett. 2013;15:718. doi: 10.1021/ol303520h.Liu W, Ackermann L. Org Lett. 2013;15:3484. doi: 10.1021/ol401535k.Takemura N, Kuninobu Y, Kanai M. Org Lett. 2013;15:844. doi: 10.1021/ol303533z.Rosen BR, Simke LR, Thuy-Boun PS, Dixon DD, Yu J-Q, Baran PS. Angew Chem. 2013;125:7458. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303838.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:7317.Wang H, Li G, Engle KM, Yu JQ, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6774. doi: 10.1021/ja401731d.Bhadra S, Matheis C, Katayev D, Gooßen LJ. Angew Chem. 2013;125:9449. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303702.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:9279.

- 3.For recent selected examples on transition metal-catalyzed C–H/O–H oxidative coupling of carboxylic acid with unactivated sp2 C–H bond, see: Li Y, Ding YJ, Wang JY, Su YM, Wang XS. Org Lett. 2013;15:2574. doi: 10.1021/ol400877q.Yang M, Jiang X, Shi WJ, Zhu QL, Shi ZJ. Org Lett. 2013;15:690. doi: 10.1021/ol303569b.Cheng XF, Li Y, Su YM, Yin F, Wang JY, Sheng J, Vora HU, Wang XS, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1236. doi: 10.1021/ja311259x.

- 4.For 3,4-benzocoumarin-containing natural products and bioactive compounds, see: Murray RDH, Mendez J, Brown SA. The Natural Coumarins: Occurrence, Chemistry, and Biochemistry. Wiley; New York: 1982. Omar R, Li L, Yuan T, Seeram NP. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:1505. doi: 10.1021/np300417q.Tibrewal N, Pahari P, Wang G, Kharel MK, Morris C, Downey T, Hou Y, Bugni TS, Rohr J. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18181. doi: 10.1021/ja3081154.For benzocoumarin-containing materials, see: Yang C, Hsia T, Chen C, Lai C, Liu R. Org Lett. 2008;10:4069. doi: 10.1021/ol801561b.Nakashima M, Clapp R. J Sousa, Nature Phys Sci. 1973;245:124.Fletcher SP, Dumur F, Pollard MM, Feringa BL. Science. 2005;310:80. doi: 10.1126/science.1117090.

- 5.For chromic acid mediated cyclization, see: Kenner GW, Murray MA, Tylor CMB. Tetrahedron. 1957;1:259.for [Pb(OAc)4]-mediated cyclization, see: Davies D, Waring C. Chem Commun. 1965:263.

- 6.For UV-promoted ArI(OCOR)2-mediated cyclization, see: Togo H, Muraki T, Yokoyama M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:7089.Togo H, Muraki T, Hoshina Y, Yamaguchi K, Yokoyama M. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1997:787.Muraki T, Togo H, Yokoyama M. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1999:1713.Furuyama S, Togo H. Synlett. 2010:2325.

- 7.For early reports on O-centered carboxylic radicals, see: Kochi JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:1811. See also ref. 11 and ref. 12.

- 8.Gallardo-Donaire J, Martin R. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9350. doi: 10.1021/ja4047894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 10.The observed selectivity is similar to that in recently reported radical- mediated C–O bond-formation reaction, see: Yuan C, Liang Y, Hernandez T, Berriochoa A, Houk HN, Siegel D. Nature. 2013;499:192. doi: 10.1038/nature12284.

- 11.For a single example of nonefficient K2S2O8-mediated cyclization of biphenyl-2-carboxylic acid, see: Brown PM, Russell J, Thomson RH, Wylie AG. J Chem Soc C. 1968:842.for examples K2S2O8-mediated reactions of carboxylic acids, see: Russell J, Thomson RH. J Chem Soc. 1962:3379.Chalmers DJ, Thomson RH. J Chem Soc C. 1966:321.

- 12.Presumably, AgNO3 increases the rate of RCO2· radical formation. For examples on AgNO3/K2S2O8-mediated radical-decarboxylation reactions of carboxylic acids, see: Anderson JM, Kochi JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:1651.Fristad WE, Klang JA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:2219.Fristad WE, Fry MA, Klang JA. J Org Chem. 1983;48:3575.

- 13.For selected recent examples of AgNO3/K2S2O8-mediated transformations, see: Seiple IB, Su S, Rodriguez RA, Gianatassio R, Fujiwara Y, Sobel AL, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13194. doi: 10.1021/ja1066459.Lockner JW, Dixon DD, Risgaard R, Baran PS. Org Lett. 2011;13:5628. doi: 10.1021/ol2023505.Fujiwara Y, Domingo V, Seiple IB, Gatassio R, Del Bel M, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3292. doi: 10.1021/ja111152z.

- 14.The hydrogen-atom abstraction mechanism was also proposed by J. Gallardo-Donaire and R. Martin, see ref. [8].

- 15.For a related Kharasch–Sosnovsky reaction’s mechanism, see: Kharasch MS, Sosnovsky G, Yang NC. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:5819.Beckwith ALJ, Zavitsas AA. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:8230.

- 16.For a review on Cu-involved SET reactions, see: Zhang C, Tang C, Jiao N. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3464. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15323h.

- 17.For recent review on homolytic aromatic substitution mechanism, see: Studer A, Curran DP. Angew Chem. 2011;123:5122. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101597.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:5018.and references therein. See also ref. 11a for examples

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.