Summary

Background

Chronic exposure to nicotine elicits physical dependence in smokers, yet the mechanism and neuroanatomical bases for withdrawal symptoms are unclear. As in humans, rodents undergo physical withdrawal symptoms after cessation from chronic nicotine characterized by increased scratching, head nods, and body shakes.

Results

Here we show that induction of physical nicotine withdrawal symptoms activates GABAergic neurons within the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN). Optical activation of IPN GABAergic neurons via light stimulation of channel rhodopsin elicited physical withdrawal symptoms in both nicotine-naïve and chronic nicotine-exposed mice. Dampening excitability of GABAergic neurons during nicotine withdrawal through IPN-selective infusion of an NMDA receptor antagonist or through blocking IPN neurotransmission from the medial habenula reduced IPN neuronal activation and alleviated withdrawal symptoms. During chronic nicotine exposure, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing the β4 subunit were upregulated in somatostatin interneurons clustered in the dorsal region of the IPN. Blockade of these receptors induced withdrawal signs more dramatically in nicotine-dependent compared to nicotine-naïve mice and activated non-somatostatin neurons in the IPN.

Conclusions

Together, our data indicate that therapeutic strategies to reduce IPN GABAergic neuron excitability during nicotine withdrawal, for example, by activating nicotinic receptors on somatostatin interneurons, may be beneficial for alleviating withdrawal symptoms and facilitating smoking cessation.

Introduction

Adverse health consequences caused by smoking kills approximately 6 million people annually making nicotine addiction the primary cause of preventable mortality in the world [1]. Smokers attempting to quit face a variety of withdrawal symptoms that oftentimes drive relapse [2]. As in humans, rodents chronically exposed to nicotine exhibit somatic (physical), as well as affective withdrawal symptoms [3]. Rodent somatic symptoms include increased scratching, head nods and body shakes [4, 5]; whereas affective symptoms include anxiety and aversion [6]. The initiation and expression of withdrawal is dependent on neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) as symptoms can be precipitated by administration of nicotinic receptor antagonists during chronic nicotine exposure [7]. While the neurocircuitry underlying withdrawal remains to be completely elucidated, the habenular-interpeduncular axis has recently been implicated in nicotine intake and aversion [8, 9]. Interestingly, direct infusion of the non-specific nAChR antagonist, mecamylamine, into the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) can precipitate somatic withdrawal in nicotine-dependent mice, suggesting that the habenular-interpeduncular axis may be important for the expression of somatic signs of nicotine withdrawal. In addition, knock-out mice that do not express nAChR α2, α5, or β4 subunits, which are particularly abundant in the IPN, exhibit fewer somatic symptoms during nicotine withdrawal [10, 11]. However, whether the IPN is activated or inhibited after chronic nicotine cessation or is sufficient to trigger somatic or affective withdrawal symptoms is unknown.

Results

GABAergic neurons in the IPN are activated during nicotine withdrawal

To determine the effects of nicotine withdrawal on neurons within the IPN, we treated C57BL/6J mice chronically with nicotine via nicotine-laced drinking water (200 μl/ml) to induce dependence. Control mice received water containing an equivalent concentration of tartaric acid (see methods and Fig. 1A). To precipitate withdrawal, mice were challenged with mecamylamine (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline. Confirming chronic nicotine exposure was sufficient to induce nicotine dependence, somatic physical withdrawal symptoms including scratching, body shakes, and head nods, as well as total withdrawal symptoms, were significantly increased in nicotine-treated mice after mecamylamine injection compared to nicotine-treated mice that received a saline injection (Fig 1B, C). In addition, the number of symptoms did not differ between nicotine-naïve mice that received mecamylamine or saline injection. Mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal in nicotine-dependent mice was also anxiogenic as mice undergoing withdrawal buried more marbles in the marble burying test (MBT) and spent less time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (EPM) compared to nicotine-naïve mice (Fig 1D, E). Increased anxiety was not an artifact of decreased locomotor activity as total arm entries in the EPM did not significantly differ between groups (Fig. 1F). To test the hypothesis that neurons within the IPN were activated during nicotine withdrawal, IPN slices were immunolabeled for c-Fos, a molecular marker of neuronal activation [12], and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) 2/1, a marker of GABAergic neurons as the IPN is a GABAergic neuron-rich brain region (Fig S1A)[13]. Interestingly, mecamylamine induced c-Fos expression predominantly in chronic nicotine-treated animals (Fig 2A, B). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of chronic treatment (F1,16 = 53.23, p < 0.001), drug (F1,16 = 124.5, p <0.001), and a significant chronic treatment×drug interaction (F1,16 = 51.70, p <0.0001). Post-hoc analysis indicated that the number of c-Fos-immunoreactive (ir) neurons was significantly increased after mecamylamine injection compared to saline injection in nicotine-dependent (p < 0.001), but not nicotine-naïve mice. In addition, the number of c-Fos-ir neurons in nicotine-dependent animals that received mecamylamine was significantly greater than the number of c-Fos-ir neurons in nicotine-naïve animals receiving mecamylamine (p < 0.001). Co-localization of c-Fos with GAD expression in mecamylamine-injected nicotine-dependent mice occurred in >80 % of neurons (Fig. 2A, insets). Together, these data suggest that mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal induces activation of primarily GABAergic neurons in the IPN.

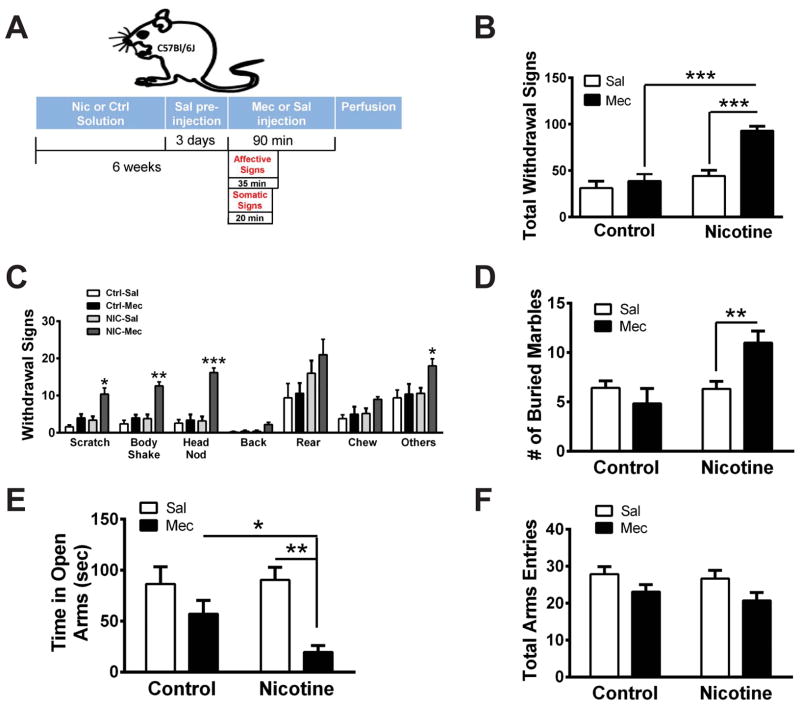

Figure 1. Mecamylamine precipitates withdrawal in nicotine-dependent mice.

A) Experimental strategy for inducing nicotine dependence/withdrawal in C57Bl/6J mice, quantifying symptoms, and perfusing brains for immunohistochemistry experiments illustrated in Figure 1. B) Averaged total somatic withdrawal signs in control and nicotine-treated animals after saline or mecamylamine (1 mg/kg, i.p., n = 5 mice/treatment) injection. Two-way ANOVA: Significant effect of chronic treatment (F1, 16 = 25.79, p < 0.0001), drug (F1, 16 = 18.16, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction (F1, 16 = 9.69, p < 0.01). C) Averaged number of individual nicotine withdrawal symptoms from (A). Two-way ANOVA: Scratches, significant effect of drug (F1,16 = 17.39, p < 0.001), and chronic treatment (F1, 16 = 13.2, p < 0.01); Body Shakes, significant effect of drug (F1,16 = 26.64, p < 0.001), chronic treatment (F1, 16 = 24.63, p < 0.001) and interaction (F1, 16 = 12.77, p < 0.01); Head Nods, significant effect of drug (F1,16 = 31.74, p < 0.001), chronic treatment (F1, 16 = 29.93, p < 0.001) and interaction (F1, 16 = 24.81, p < 0.001). D) Average number of marbles buried in the MBT in control and nicotine-treated animals after saline or mecamylamine injection (n = 7–24 mice/treatment). Two-way ANOVA: Significant effect of chronic treatment (F1, 57 = 7.93, p < 0.01), not drug, and a significant interaction (F1, 57 = 8.47, p < 0.01). E) Average time spent in the open arms of the EPM in mice (n = 7–10) treated as in (D). Two-way ANOVA: Significant effect of drug (F1, 31 = 12.79, p < 0.01). F) Average total arm entries in the EPM in mice from (E). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Bonferroni post-hoc test.

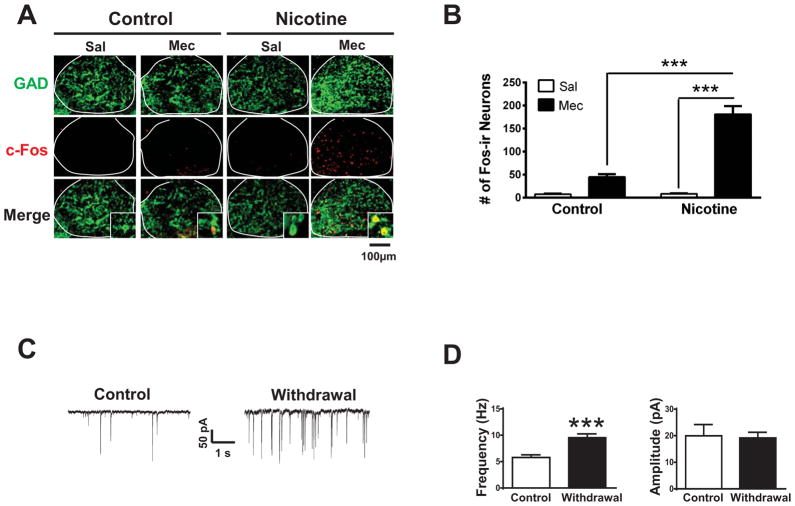

Figure 2. Nicotine withdrawal activates IPN GABAergic neurons.

A) Representative photomicrographs of IPN slices immunolabeled for GAD2/1 (green, top panels) and c-Fos (red, middle panels) from control or nicotine-treated mice that received saline (Sal) or mecamylamine (Mec) injections as indicated. Bottom panels depict merged signals. Insets show 630x images. Co-localization of c-Fos in GAD immunopositive neurons was apparent after mecamylamine injections. Note that a similar pattern of c-Fos labeling after mecamylamine challenge was observed in the IPN of mice that self-administer nicotine in a 24-hr two-bottle choice assay (data not shown). B) Average number of c-Fos immunoreactive (ir) IPN neurons under each condition from panel (A) (n = 5 mice/treatment). Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test. C) Representative whole-cell recordings illustrating sEPSCs from IPN neurons of control mice (left) and nicotine-withdrawn mice (right). D) Average sEPSC frequency (left) and amplitude (right) in IPN neurons of control (n=26 neurons/treatment) and nicotine-withdrawn mice (n=45 neurons/treatment). Error bars indicate SEM. Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. *** p < 0.001.

To test if excitability of IPN neurons would increase during spontaneous nicotine withdrawal, we treated mice chronically with nicotine (or control solution) as above. Spontaneous withdrawal was then elicited by replacing the nicotine drinking solution with water. Twenty-four hours after nicotine cessation, brains were sliced and whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made in IPN neurons to measure spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents (sEPSCs, Fig. 2C, D). EPSC analysis revealed that in comparison to control, neurons within the IPN of withdrawn mice had increased sEPSC frequency (t68.9=4.35, p < 0.001), but not amplitude, indicating increased excitatory input elicited by increased release of glutamate in the IPN. GAD expression (both GAD1 and 2) could be detected in >70 % of neurons as measured by single neuron RT-PCR (Fig. S1B).

Optical activation of GAD2-expressing IPN neurons triggers somatic withdrawal symptoms

To test the hypothesis that activation of GABAergic neurons within the IPN was sufficient to elicit the observed nicotine withdrawal symptoms, we selectively expressed channel rhodopsin with an eYFP tag (ChR2-eYFP) in the IPN of GAD2-Cre mice using AAV2-mediated gene delivery of a plasmid containing ChR2-eYFP in a double inverted open reading frame (Fig S2A) [14, 15]. Four to six weeks post-infection, significant eYFP signal was observed in GAD2/1-expressing neurons indicating proper localization to GABAergic neurons (Fig. S2B). Light stimulation of ChR2-eYFP-positive neurons in IPN midbrain slices from ChR2-eYFP-infected GAD2-Cre mice elicited robust trains of action potentials; whereas neurons from control animals did not respond to light (Fig. S2C). These data confirmed that ChR2-eYFP was expressed and functional within the IPN.

To activate GABAergic neurons in vivo, GAD2-Cre mice were infected with AAV2 ChR2-eYFP or control (AAV2-eGFP) virus and optic cannulas were implanted targeting the IPN in both chronic nicotine-treated and nicotine-naïve GAD2-Cre mice 4–6 weeks post-infection. Blue light (via 473 nM LED) was delivered to the IPN in vivo and somatic withdrawal symptoms were scored (Fig. 3). Ten pulses of light at 50 Hz were delivered every 5 s for 10 min (Fig. 3A). This light stimulation protocol was used to induce phasic firing of these neurons [16–18], a stimulation that is also sufficient to induce c-Fos expression [19], mimicking what is observed during mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal. Light delivery into the IPN elicited significant withdrawal-like symptoms in chronic nicotine-treated, ChR2-eYFP-expressing GAD2-Cre mice including scratching (p<0.05), body shakes (p<0.001), and head nodding (p <0.001) compared to light delivery in control mice, which elicited few symptoms (Fig. 3A). A similar phenotype was also observed in nicotine-naïve animals (Fig. S3). To determine if activation of the same neurons within the IPN also triggered the anxiogenic effects of withdrawal, we stimulated neurons as described above and measured anxiety-like behavior in the EPM and MBT assays (Fig. 3B). Time spent in the open arms of the EPM, as well as total arm entries, did not differ between ChR2-eYFP-expressing GAD2-Cre mice and control animals during light stimulation. Similarly, the number of marbles buried in the MBT was not significantly different in ChR2-eYFP-expressing GAD2-Cre mice at baseline (without light stimulation) compared to during light stimulation. To measure expression and function of ChR2-eYFP in infected animals, we isolated brains after light stimulation and verified eYFP expression under fluorescence microscopy (Fig 3C). In addition, the number of c-Fos-ir IPN neurons in ChR2-eYFP-infected mice was significantly greater after light stimulation compared to controls, indicating neuronal activation by light stimulus (Fig. 3C, D, p < 0.001).

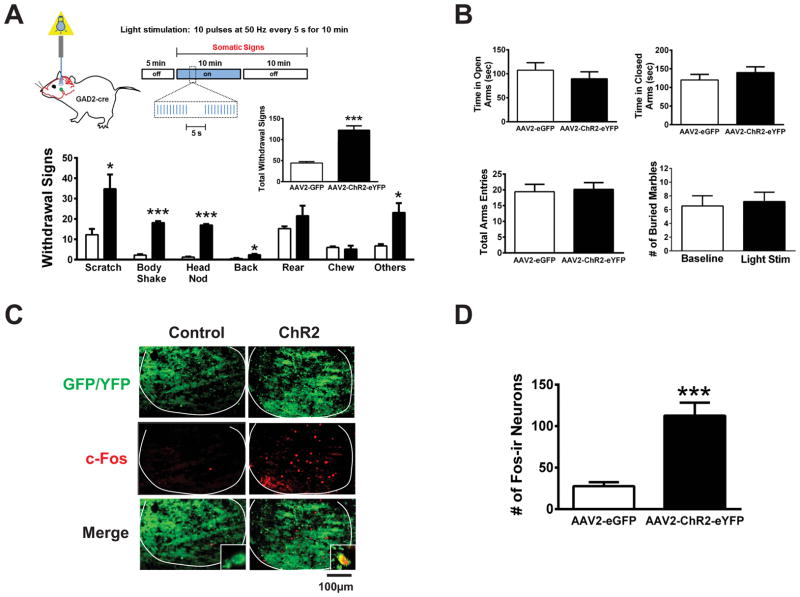

Figure 3. Activation of GABAergic neurons triggers somatic withdrawal symptoms.

A) Top, Schematic of experimental strategy and neuronal activation protocol. Bottom, averaged individual withdrawal symptom behaviors elicited by light exposure in chronic nicotine-treated GAD2-Cre mice infected with AAV2-eGFP (Control, white bars) or AAV2-ChR2-eYFP (black bars, n = 7 mice/condition). Unpaired two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction revealed that light stimulation induced a significant increase in Scratching (t5.22 = 2.96), Body Shakes (t6.54 = 18.2), Head Nods (t5.52 = 26.2), Backings (t6.14 = 3.24) and Other symptoms (t4.27 = 3.49) in AAV2-CHR2-eYFP-infected mice compared to AAV2-eGFP-infected mice (n = 4–6 mice/group). Inset, total signs during light stimulation (unpaired two-tailed t-test, t7 = 6.58). B) Average time spent in the open arms (top, left) and closed arms (top, right), and total arm entries (bottom, left) in the EPM during light stimulation in nicotine-treated GAD2-Cre mice infected with AAV2-eGFP or AAV2-CHR2-eYFP (n = 7–10 mice/group). Average number of marbles buried in the MBT in AAV2-CHR2-eYFP-infected GAD2-Cre mice at baseline prior to light stimulation and during light stimulation (bottom, right, n = 11). C) Representative IPN sections from AAV2-eGFP- and AAV2 ChR2-eYFP-infected mice after light stimulation. Sections were immunolabeled for c-Fos (red). Insets show 630x images. Co-localization of c-Fos in eYFP expressing neurons was apparent after light stimulation. D) Averaged total number of IPN c-Fos-ir neurons after light stimulation (t10 = 5.18). Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Glutamate release from MHb-IPN afferents is necessary for somatic nicotine withdrawal signs

We next explored the potential mechanism underlying activation of IPN GABAergic neurons during nicotine withdrawal. To test the hypothesis that increased glutamate release in the IPN during nicotine withdrawal is necessary for the observed increase in neuronal activation, we infused saline or the NMDA receptor antagonist, AP5, prior to infusion of mecamylamine, directly into the IPN of control and chronic nicotine-dependent mice followed by c-Fos analysis (Fig. 4A, B). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of chronic treatment (F1,10 = 52.45, p < 0.0001), infusion (F1,10 = 37.43, p < 0.0001), and a significant chronic nicotine×infusion interaction (F1,10 = 12.97, p < 0.01). Post-hoc analysis revealed that infusion of mecamylamine into the IPN was sufficient to increase the number of c-Fos-ir neurons in nicotine-dependent mice compared to mecamylamine infusion in nicotine-naïve animals (p < 0.001). In addition, pre-infusion of AP5 reduced the number of c-Fos-ir neurons elicited by mecamylamine in nicotine-dependent but not naïve animals (p < 0.001). To test the hypothesis that reducing activation of IPN neurons via an NMDA antagonist could alleviate withdrawal symptoms, we infused saline or AP5 directly into the IPN of nicotine-dependent mice undergoing spontaneous withdrawal (Fig. 4C). Saline infusion did not affect withdrawal symptoms as symptoms were significantly increased compared to baseline responses (symptoms in nicotine-treated mice prior to cessation). In contrast, AP5 infusion during spontaneous withdrawal significantly decreased individual symptoms including scratching and body shakes, as well as the number of total symptoms compared to a saline infusion (Fig. 4C, inset). As we have done previously, guide cannulas were verified to target the IPN in each animal [20] (Fig. S4A). Recent data indicate that cholinergic neuron afferents projecting from the medial habenula (MHb) also synthesize and release glutamate into the IPN [21]. To test the hypothesis that MHb neurons provide the source of glutamate that stimulates IPN neurons during withdrawal, we implanted mice with cannulas targeting the MHb and infused lidocaine to block neurotransmission during spontaneous nicotine withdrawal [8] (Fig. 4D, S4B). Lidocaine infusion significantly blocked both individual and total somatic nicotine withdrawal signs compared to a saline infusion. In addition, infusion of lidocaine into the MHb prior to mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal also reduced neuronal activation of IPN neurons as measured by c-Fos (Fig. S5, p < 0.01).

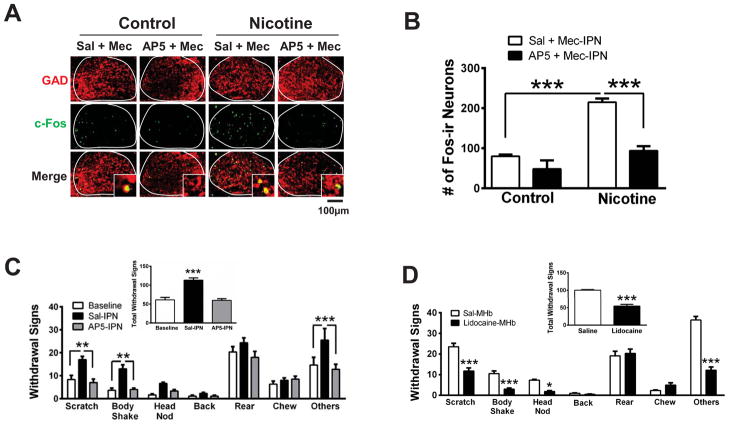

Figure 4. Glutamatergic signaling from MHb projections is critical for IPN neuronal activation during withdrawal and expression of somatic withdrawal symptoms.

A) Representative IPN sections from control or chronic nicotine-treated mice after IPN infusion of Sal + Mec, or AP5 + Mec. Sections were immunolabeled for GAD2/1 (red, top panels) and c-Fos (green, middle panels). Bottom panels depict merged signals. Insets show 630x images and co-localization of c-Fos in GAD immunopositive neurons. B) Averaged total number of c-Fos-ir IPN neurons for each condition in panel A (control mice, n = 3 mice/treatment; chronic nicotine-treated mice, n=4 mice/treatment). C) Averaged number of individual spontaneous withdrawal signs in nicotine-dependent mice at baseline (prior to cessation), after IPN-infusion of saline, or after IPN-infusion of AP5 (n = 6 mice/treatment). One-way repeated measure ANOVA for each symptom indicated a significant main effect of infusion on Scratches (F2,10 = 13.65, p < 0.01), Body Shakes (F2,10 = 33.5, p < 0.001), (Head Nods, F2,10 = 27.34, p < 0.001), (Backing, F2,10 = 4.15, p < 0.05) and Others (F2, 10 = 4.96, p < 0.05). Inset, average total number of withdrawal symptoms. One-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of infusion on total number of symptoms (F2,10 = 30.73, p < 0.001). D) Averaged number of individual spontaneous withdrawal signs in nicotine-dependent mice undergoing spontaneous withdrawal after saline infusion (white bars) or lidocaine infusion (black bars) into the MHb (n = 6 mice/group). Unpaired two-tailed t-tests revealed that lidocaine induced a significant reduction in Scratching (t10= 5.08), Body Shakes (t10= 5.16), Head Nods (t10= 8.64), and Other symptoms (t10= 10.33) compared to saline infusion. Inset, total withdrawal symptoms after MHb saline or lidocaine infusions (unpaired two-tailed t-test, t10 = 8.71). Error bars indicate SEM. * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

IPN Sst interneurons express nAChRs containing the β4 subunit that are upregulated during chronic nicotine exposure

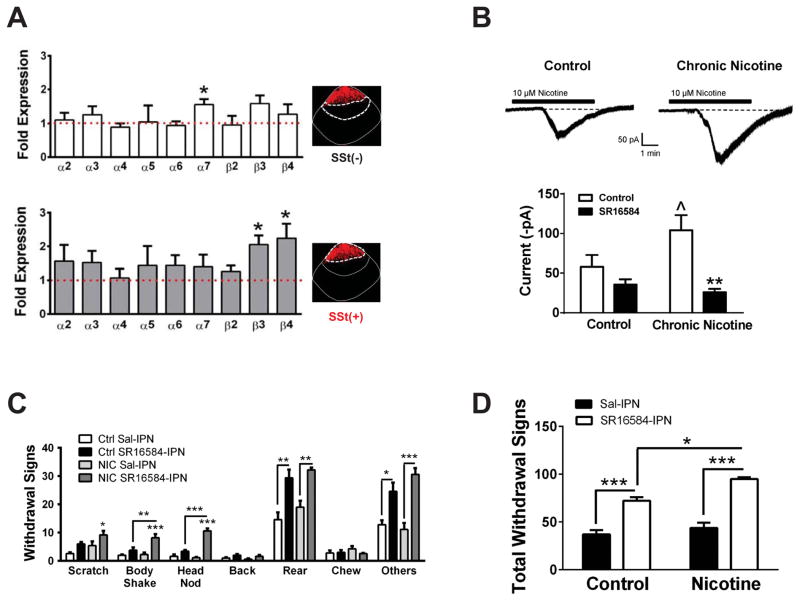

Both nicotine cessation and mecamylamine induce withdrawal symptoms, presumably by decreasing/blocking activity of nAChRs. How might a decrease in activity of excitatory nAChRs lead to neuronal activation? This scenario could occur if nAChRs were prominently expressed in a population of inhibitory interneurons leading to disinhibition of projection neurons or glutamate release from presynaptic terminals upon reduced nAChR activity. To explore this possibility, we examined nAChR expression and function in IPN somatostatin (Sst) interneurons, a sub-population of interneurons known to exist in the IPN [22] and shown to modulate glutamate release from presynaptic terminals in other brain regions [23]. We laser-dissected Sst-immunopositive and –immunonegative IPN neurons and compared nAChR subunit expression from nicotine-dependent and nicotine-naïve mice using qRT-PCR (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, immunolabeling of Sst neurons revealed that they are densely clustered within the very dorsal region of the IPN (Fig. 5A, insets). Expression of α2-α7 and β2-β4 nAChR subunits was detected in both neuronal populations. Expression of β3 and β4 nAChR subunits was significantly upregulated in Sst-immunopositive neurons from chronic nicotine-treated mice compared to nicotine-naïve animals (p < 0.05, Fig. 5A, bottom); whereas only the α7 subunit was modestly upregulated in Sst-immunonegative neurons from chronic nicotine-treated mice (Fig. 5A, top). To determine if nAChRs in Sst neurons were functionally upregulated after chronic nicotine exposure, we measured whole-cell currents in response to nicotine in IPN slices from nicotine-treated and nicotine-naïve mice. Neurons in the dorsal region of the IPN were targeted based on the observed pattern of Sst-immunolabeling. Neuronal identity was confirmed by single-neuronal RT-PCR (Fig. S6A). This analysis also revealed that Sst neurons predominantly express GAD1; whereas GAD2 expression was detected in only 10/43 neurons (~23 %) of Sst-expressing neurons. Nicotine (10 μM) elicited robust inward currents in IPN Sst neurons that were modestly but significantly larger in slices from chronic nicotine-treated mice (Fig. 5B, ~80 % increase, p < 0.05). To determine if the nAChR subtype underlying responses to nicotine in Sst IPN neurons contained, in part, the β4 subunit, we measured nicotine-induced currents in the presence of SR16584 (20 μM), an antagonist selective for nAChRs containing the β4 subunit [24]. In nicotine-naïve slices, SR16584 exhibited a trend to reduce currents induced by nicotine in Sst neurons (~40 % reduction); whereas in slices from nicotine-treated mice, SR16584 significantly and robustly reduced nicotine-elicited currents (~75 %, p<0.01).

Figure 5. A role for Sst interneuron nAChRs containing theβ4 subunit in somatic nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

A) Comparison of nAChR subunit gene expression in Sst-immunopositive (top) and -immunonegative (bottom) neurons from the IPN of nicotine-naïve and chronic nicotine-treated mice. Fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Red dotted line represents equal gene expression between nicotine-naïve and chronic nicotine-treated animals (n = 3 mice/group). Insets, representative photomicrographs of IPN sections immunolabeled for Sst. White dotted lines represent regions where neurons were laser-captured for each analysis. * p < 0.05 gene expression of nAChR subunit from nicotine treated compared to control mice (Unpaired t-tests: α7: t4 = 3.13; β3: t4 = 3.85; β4: t4 = 2.94). B) Top, representative whole-cell currents in response to 10 μM nicotine (bath-applied, black bars) in IPN Sst neurons from nicotine-naïve (left) and chronic nicotine-treated mice (right). Bottom, average peak currents from nicotine whole-cell responses in Sst neurons from nicotine-naïve and chronic nicotine-treated mice in the absence (white bar) and presence (black bar) of SR16584. ^ p < 0.05 compared to neurons from nicotine-naïve mice (t26 = 1.89). ** p < 0.01 compared to control responses in neurons from nicotine-treated mice (t20 = 3.02). C) Averaged number of individual spontaneous withdrawal signs in control and chronic nicotine-treated mice after IPN infusion of saline or SR16584 (n = 5–8 mice/group). Two-way ANOVA: Scratches, significant effect of antagonist (F1,19 = 7.52, p < 0.05), and chronic treatment (F1, 19 = 5.14, p < 0.05); Body Shakes, significant effect of antagonist (F1,19 = 22.02, p < 0.001), chronic treatment (F1, 19 = 9.18, p < 0.01) and interaction (F1, 19 = 7.63, p < 0.05); Head Nods, significant effect of antagonist (F1,19 = 34.38, p < 0.001), chronic treatment (F1, 19 = 96.64, p < 0.001) and interaction (F1, 19 = 44.78, p < 0.001); Rearing, significant effect of drug (F1,19 = 33.95, p < 0.001); Other symptoms, significant effect of antagonist (F1,19 = 62.72, p < 0.001). D) Average total withdrawal symptoms from (C). Two-way ANOVA indicated a statistically significant effect of antagonist (F1,19 = 9.09, p < 0.01) and chronic treatment (F1,19 = 77.77, p < 0.001). Error bars indicate SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Bonferroni post-hoc.

Blockade of β4 nAChR signaling in the IPN elicits somatic nicotine withdrawal signs

To determine if blockade of nAChRs containing the β4 subunit could elicit somatic withdrawal symptoms in mice similar to mecamylamine, we infused SR16584 into the IPN of nicotine-treated and control mice. SR16584 induced withdrawal-like symptoms in nicotine-naïve animals compared to saline infusion (predominantly rearing and other symptoms, Fig. 5C). However, SR16584 infusion induced greater number of individual symptoms (including head nodding and body shaking), as well as total symptoms in chronic nicotine-treated mice compared to nicotine-naïve animals indicating a role for upregulation of nAChRs containing the β4 subunit in physical withdrawal symptoms (Fig. 5D). Based on our hypothesis, we would expect that blockade of β4 nAChRs would activate non-Sst neurons within the IPN triggering somatic withdrawal symptoms. To test this hypothesis, we immunolabeled IPN sections for c-Fos and Sst expression after IPN infusion of SR16584 (Fig. S6B). We were unable to detect c-Fos in Sst-immunopositive neurons; whereas c-Fos was induced by antagonist in Sst-immunonegative neurons. The number of c-Fos neurons induced by SR16584 infusion was significantly greater in both nicotine-naïve and nicotine-treated animals compared to a saline infusion. In addition, the number of c-Fos immunopositive neurons was significantly greater in chronic nicotine-treated mice compared to nicotine-naïve mice.

Discussion

Here we show that withdrawal from chronic nicotine treatment activates GABAergic neurons of the IPN. GABAergic neuronal activation during withdrawal is mediated, at least in part, by enhancement of excitatory input as EPSC frequencies, but not amplitudes, were increased in GABAergic neurons from nicotine-withdrawn mice compared to nicotine-naïve animals. These data suggest increased glutamate release mediates enhanced activation of IPN GABAergic neurons during nicotine withdrawal. Dampening excitability of IPN GABAergic neurons using an NMDA receptor antagonist reduced neuronal activation and alleviated withdrawal symptoms suggesting that increased glutamate release into the IPN is necessary for expression of somatic withdrawal symptoms. The IPN receives robust input from cholinergic neurons of the MHb [25]. Recent data indicate that these same inputs also synthesize and release glutamate [21]. Consistent with this idea, blocking neurotransmission of the MHb inhibited activation of the IPN during mecamylamine-precipitated nicotine withdrawal and alleviated withdrawal symptoms. Enhanced excitability of IPN GABAergic neurons is mediated by glutamatergic signaling whether withdrawal is precipitated by a mecamylamine infusion or elicited by nicotine abstinence, suggesting the mechanism is similar between both withdrawal paradigms and likely involves decreased nAChR signaling. Indeed, we identified Sst-immunopositive interneurons within the dorsal region of the IPN that robustly expressed nAChRs. Within this population of interneurons, chronic nicotine upregulated gene expression of β3 and β4 nAChR subunits and yielded more robust nicotine-induced currents that were sensitive to a β4 nAChR antagonist. Interestingly, the β3 and β4 nAChRs subunits coassemble in the IPN to form a unique nAChR subtype [26]. IPN infusion of a β4 nAChR antagonist triggered robust withdrawal symptoms in nicotine-treated mice and activated non-Sst IPN neurons, indicating a role for β4 nAChRs in somatic nicotine withdrawal symptoms. These data are in agreement with previous studies on β4 nAChR subunit knock-out mice, which fail to express somatic nicotine withdrawal symptoms [11, 27]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a chronic nicotine-mediated neuroadaptation in the IPN.

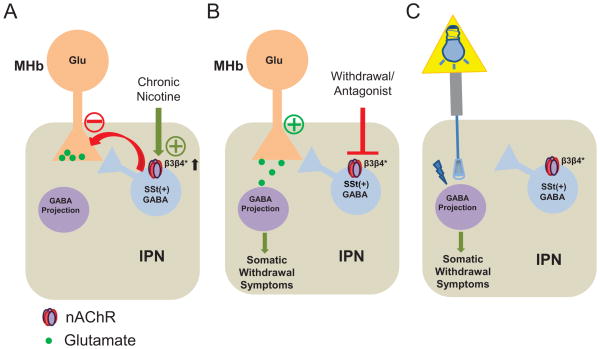

Together, our data allow us to provide a mechanistic model underlying expression of somatic nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Fig. 6). GABAergic (presumably projection) neurons within the IPN receive glutamatergic input from the MHb. Inhibition of MHb glutamatergic terminals is modulated by Sst interneurons clustered in the dorsal portion of the IPN, consistent with the known effect of Sst interneurons in regulating presynaptic glutamate release [23]. During chronic nicotine exposure, nAChRs containing the β3 and β4 subunits are upregulated in Sst interneurons to help increase drive of Sst interneuron activity and offset (i.e., inhibit) glutamate release from the MHb (Fig. 6A). During spontaneous withdrawal or mecamylamine-precipitated withdrawal, decreased nAChR signaling reduces Sst interneuron activity thereby disinhibiting glutamate release from the MHb. The increased glutamate release increases excitability of GABAergic neurons thereby eliciting somatic nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Fig. 6B). In this scenario, it is likely that a specific population of GABAergic neurons (i.e., non-Sst GABAergic or projection neurons) receive glutamatergic input from MHb projections; whereas Sst neurons may receive MHb cholinergic input, although additional experiments will be needed to test this hypothesis. In our optogenetic experiments, this mechanism is bypassed: ChR2 is expressed in GAD2-expressing neurons, which are predominantly non-Sst neurons as GAD2 was detected in only a small fraction of Sst neurons. Optical activation of GAD2-expressing IPN neurons directly triggers somatic withdrawal-like symptoms regardless of nicotine exposure, indicating that activation of these neurons is sufficient for expression of somatic withdrawal behaviors (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Mechanistic model of somatic nicotine withdrawal symptom expression.

A) The IPN receives glutamatergic input (Glu) from the MHb. Presynaptic glutamate release is controlled, in part, by Sst neurons which express nAChRs. Nicotine activates Sst neurons through nAChRs containing the β3 and β4 subunits (β3β4* nAChRs) inhibiting MHb glutamate release (Red arrow). With chronic nicotine exposure these nAChRs are upregulated. B) During nicotine withdrawal, decreased nAChR signaling either through nicotine cessation or via nAChR blockade with an antagonist, reduces Sst neuron activation, disinhibiting glutamate release from MHb presynaptic terminals. The increased glutamate release stimulates activity of IPN GAD2-expressing (presumably projection) neurons eliciting somatic withdrawal signs. C) In the optogenetic experiments, ChR2 is expressed in GAD2-expressing neurons only. Light stimulation ultimately drives activation of these neurons triggering somatic withdrawal signs.

Interestingly, activation of IPN GAD2-expressing neurons did not induce anxiety, suggesting that other brain regions may mediate affective nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Alternatively, distinct populations of neurons within the IPN may be differentially involved in somatic and affective withdrawal symptoms. Regardless, these data are consistent with previous studies indicating somatic and affective withdrawal behaviors, at least in rats, are dissociable [28]. Future experiments are underway to characterize IPN sub-regions and neuronal sub-population in the context of drug withdrawal behaviors.

Together, our data are the first demonstrating direct activation of a brain region eliciting physical withdrawal symptoms. Additional brain regions have been implicated in physical symptoms of nicotine withdrawal including the MHb (confirmed here) and most recently the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which also projects to the IPN [10, 29–32]. Thus, the paraventricular nucleus may also be a part of the neural network underlying nicotine somatic withdrawal symptoms. Additional studies should focus on further mapping this network in an effort to identify neuroanatomical targets to reduce withdrawal symptoms. In summary, our data indicate that withdrawal from chronic nicotine activates GABAergic neurons in the IPN. Activation of these neurons is both necessary and sufficient for the induction of somatic withdrawal symptoms. Reducing activation of these neurons, through stimulating Sst interneuron nAChRs, for example, may represent a potential novel therapeutic strategy to alleviate withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice and GAD2-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory, West Grove, PA, USA), were used in all experiments. GAD2-Cre mice have been described previously and have been back-crossed to a C57BL/6J background for least one generation[15]. Animals were kept on a standard 12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM and off at 7:00 PM. Behavioral experiments were performed during the light cycle. Independent groups of animals were used for each behavioral experiment unless otherwise noted. Mice were housed 4/cage and received food and drinking solution ad libitum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals provided by the National Research Council [33], as well as with an approved animal protocol from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Drugs and drinking solution

Nicotine and control drinking solutions were prepared from nicotine hydrogen tartrate or L-tartaric acid (Sigma-Aldrich), which were dissolved in tap water with concentrations of 200 μg/ml and 300 μg/ml, respectively. Saccharin Sodium (Fisher Scientific) was added to each solution to sweeten the taste with a concentration of 3 mg/ml. Mecamylamine hydrochloride (1 mg/kg, intraperitoneally [i.p.]) was dissolved in sterile saline. For intra-IPN drug infusions, mecamylamine (2 μg/μl) and AP5 (2μg/μl) were dissolved in sterile saline. SR 16584 (2.7 μg/μl) was dissolved in 50% DMSO. For intra-mHb drug infusion, lidocaine (10 μg/μl) was dissolved in sterile saline. Nicotine and mecamylamine doses are reported as free base.

Mecamylamine-precipitated and spontaneous nicotine withdrawal

Mice received chronic nicotine treatment via nicotine in the drinking water (i.e. water and nicotine was received from a single bottle) beginning at age 6 weeks. After 6 weeks of nicotine/control drinking solution and 3 days of habituation to saline i.p. pre-injection, mice were injected (i.p) with 1 mg/kg of mecamylamine or saline, and immediately put back into their home cages. Somatic withdrawal signs were observed 2 min later and recorded for 20 min. Typical signs include scratching, body shaking, head nodding, backing, rearing, chewing, which were tabulated once/event. “Other” behaviors were defined as grooming, circling, jumping, cage scratching, ptosis and digging, and were scored no more than one event/minute. Ninety min post-injection, mice were perfused and the brains were removed for immunohistochemistry. For spontaneous withdrawal, mice were treated with nicotine or control solution for 6 weeks as above. To induce spontaneous withdrawal nicotine solution was replaced with control solution. Withdrawal behaviors were measured 24 hours after nicotine cessation. Similar somatic withdrawal signs were observed in mice receiving a 24 hr/day two bottle choice test (nicotine and control solution) indicating that withdrawal signs also occurred when nicotine exposure was not “forced”.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Nicotine withdrawal activates GABAergic neurons in the IPN

Activation of GAD2-expressing IPN neurons triggers physical withdrawal symptoms.

Neurotransmission from MHb afferents is necessary for somatic withdrawal expression.

Blockade of IPN β4 nAChRs elicits somatic nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Karl Deisseroth for the AAV-Ef1A-DIO-ChR2-eYFP plasmid and Dr. Guangping Gao for AAV-eGFP and for packaging of viral plasmids. We also thank Dr. Kensuke Futai for insightful discussion. This work was supported by award numbers R21DA025853 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and R01AA017656 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Picciotto MR, Kenny PJ. Molecular mechanisms underlying behaviors related to nicotine addiction. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2013;3:a012112. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benowitz NL. Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: implications for smoking cessation treatment. Am J Med. 2008;121:S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenny PJ, Markou A. Neurobiology of the nicotine withdrawal syndrome. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:531–549. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damaj MI, Kao W, Martin BR. Characterization of spontaneous and precipitated nicotine withdrawal in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:526–534. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grabus SD, Martin BR, Batman AM, Tyndale RF, Sellers E, Damaj MI. Nicotine physical dependence and tolerance in the mouse following chronic oral administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;178:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson KJ, Martin BR, Changeux JP, Damaj MI. Differential role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in physical and affective nicotine withdrawal signs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salas R, Main A, Gangitano D, De Biasi M. Decreased withdrawal symptoms but normal tolerance to nicotine in mice null for the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler CD, Lu Q, Johnson PM, Marks MJ, Kenny PJ. Habenular alpha5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature. 2011;471:597–601. doi: 10.1038/nature09797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frahm S, Slimak MA, Ferrarese L, Santos-Torres J, Antolin-Fontes B, Auer S, Filkin S, Pons S, Fontaine JF, Tsetlin V, et al. Aversion to nicotine is regulated by the balanced activity of beta4 and alpha5 nicotinic receptor subunits in the medial habenula. Neuron. 2011;70:522–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salas R, Sturm R, Boulter J, De Biasi M. Nicotinic receptors in the habenulo-interpeduncular system are necessary for nicotine withdrawal in mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3014–3018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4934-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salas R, Pieri F, De Biasi M. Decreased signs of nicotine withdrawal in mice null for the beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10035–10039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1939-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole AJ, Saffen DW, Baraban JM, Worley PF. Rapid increase of an immediate early gene messenger RNA in hippocampal neurons by synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Nature. 1989;340:474–476. doi: 10.1038/340474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaja MD, Flumerfelt BA, Hrycyshyn AW. Glutamate decarboxylase immunoreactivity in the rat interpeduncular nucleus: a light and electron microscope investigation. Neuroscience. 1989;30:741–753. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenno L, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. The development and application of optogenetics. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:389–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsiani D, Fu Y, Lu J, Lin Y, et al. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan KR, Yvon C, Turiault M, Mirzabekov JJ, Doehner J, Labouebe G, Deisseroth K, Tye KM, Luscher C. GABA neurons of the VTA drive conditioned place aversion. Neuron. 2012;73:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai HC, Zhang F, Adamantidis A, Stuber GD, Bonci A, de Lecea L, Deisseroth K. Phasic firing in dopaminergic neurons is sufficient for behavioral conditioning. Science. 2009;324:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1168878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tye KM, Mirzabekov JJ, Warden MR, Ferenczi EA, Tsai HC, Finkelstein J, Kim SY, Adhikari A, Thompson KR, Andalman AS, et al. Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature. 2013;493:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covington HE, 3rd, Lobo MK, Maze I, Vialou V, Hyman JM, Zaman S, LaPlant Q, Mouzon E, Ghose S, Tamminga CA, et al. Antidepressant effect of optogenetic stimulation of the medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16082–16090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Pang X, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Activation of alpha4* nAChRs is necessary and sufficient for varenicline-induced reduction of alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10169–10176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren J, Qin C, Hu F, Tan J, Qiu L, Zhao S, Feng G, Luo M. Habenula “cholinergic” neurons co-release glutamate and acetylcholine and activate postsynaptic neurons via distinct transmission modes. Neuron. 2011;69:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmendinger LM, Moore RY. Interpeduncular nucleus organization in the rat: cytoarchitecture and histochemical analysis. Brain Res Bull. 1984;13:163–179. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehm S, Betz H. Somatostatin inhibits excitatory transmission at rat hippocampal synapses via presynaptic receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4066–4075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04066.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaveri N, Jiang F, Olsen C, Polgar W, Toll L. Novel alpha3beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-selective ligands. Discovery, structure-activity studies, and pharmacological evaluation. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2010;53:8187–8191. doi: 10.1021/jm1006148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:503–513. doi: 10.1038/nrn2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grady SR, Moretti M, Zoli M, Marks MJ, Zanardi A, Pucci L, Clementi F, Gotti C. Rodent habenulo-interpeduncular pathway expresses a large variety of uncommon nAChR subtypes, but only the alpha3beta4* and alpha3beta3beta4* subtypes mediate acetylcholine release. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2272–2282. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5121-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoker AK, Olivier B, Markou A. Role of alpha7- and beta4-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the affective and somatic aspects of nicotine withdrawal: studies in knockout mice. Behavior genetics. 2012;42:423–436. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9511-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins SS, Stinus L, Koob GF, Markou A. Reward and somatic changes during precipitated nicotine withdrawal in rats: centrally and peripherally mediated effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:1053–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plaza-Zabala A, Flores A, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. Hypocretin/orexin signaling in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus is essential for the expression of nicotine withdrawal. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albanese A, Castagna M, Altavista MC. Cholinergic and non-cholinergic forebrain projections to the interpeduncular nucleus. Brain Res. 1985;329:334–339. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contestabile A, Flumerfelt BA. Afferent connections of the interpeduncular nucleus and the topographic organization of the habenulo-interpeduncular pathway: an HRP study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1981;196:253–270. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamill GS, Jacobowitz DM. A study of afferent projections to the rat interpeduncular nucleus. Brain Res Bull. 1984;13:527–539. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.