Abstract

Many bacteria use quorum sensing (QS) as an intercellular signaling mechanism to regulate gene expression in local populations. Plant and algal hosts, in turn, secrete compounds that mimic bacterial QS signals, allowing these hosts to manipulate QS-regulated gene expression in bacteria. Lumichrome, a derivative of the vitamin riboflavin, was purified and chemically identified from culture filtrates of the alga Chlamydomonas as a QS signal-mimic compound capable of stimulating the Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasR QS receptor. LasR normally recognizes the N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) signal, N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL). Authentic lumichrome and riboflavin stimulated the LasR receptor in bioassays, and lumichrome activated LasR in gel shift experiments. Amino acid substitutions in LasR residues required for AHL binding altered responses to both AHLs and lumichrome/riboflavin. These results and docking studies indicate that the AHL binding pocket of LasR recognizes both AHLs and the structurally dissimilar lumichrome/riboflavin. Bacteria, plants and algae commonly secrete riboflavin and/or lumichrome, raising the possibility that these compounds could serve as either QS signals or as interkingdom signal-mimics capable of manipulating QS in bacteria with a LasR-like receptor.

Keywords: agonist, lasI, red fluorescent protein, rsaL

Introduction

Quorum sensing (QS) involves the synthesis and exchange of specific signal molecules between cells in a local population of bacteria (Bassler and Losick, 2006). When sufficiently high levels of the QS signal accumulate in the cells, changes in gene expression are triggered. This regulatory mechanism enables nearby sibling cells to coordinate behaviors such as motility, mating, stress responses, and biofilm formation. The global importance of QS is indicated by estimates that 5-20% of the genes/proteins in bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa are directly or indirectly subject to QS regulation (Arevalo-Ferro et al., 2003; Vasil, 2003).

Since a variety of important bacterial pathogens depend on QS regulation to induce gene expression related to virulence, tolerance of antibiotics, and biofilm formation, there has been growing interest in finding ways to disrupt bacterial QS (Dong and Zhang, 2005; Persson et al., 2005; Rasmussen and Givskov, 2006; Riedel et al., 2006). Algae, fungi and higher plants have been found to synthesize compounds that can disrupt QS regulation in bacteria by interfering with signal perception. The best-studied example of interference with QS perception involves the halogenated furanones of a marine red alga, Delisea pulchra. The furanones were recognized as being structurally similar to the N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) QS signals used by various gram-negative bacteria and they were shown to be generally effective inhibitors of QS in such bacteria (Givskov et al., 1996). The Delisea furanones and synthetic analogs appear to act by binding to the LuxR-like protein receptors for AHL QS signals in gram negative bacteria, enhancing the rate of proteolytic degradation of those receptors and thus effectively removing the receptors from a role in QS regulation (Koch et al., 2005; Manefield et al., 2002).

Considerably less is known about the QS-active compounds produced by other eukaryotes. Roots and leaves of various higher plant species secrete QS-active compounds capable of stimulating or inhibiting AHL receptor-mediated gene expression in bacterial reporter strains that synthesize no AHL signals of their own (Degrassi et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2007; Karamanoli and Lindow, 2006; Teplitski et al., 2000). None of these compounds have been chemically identified. However, most of the active compounds in root exudates partition differently in organic solvents than bacterial AHLs, and most of them stimulated QS regulated gene expression (agonists) rather than inhibiting such expression (antagonists). Thus, these plant compounds appear to be different from both bacterial AHLs and the Delisea furanones. Compounds that inhibit QS responses mediated specifically by the LuxR AHL receptor have also been detected in plant extracts (Persson et al., 2005), especially garlic (Bjarnsholt et al., 2005).

In order to determine the chemical nature of a QS agonist produced by a eukaryote, we fractionated culture filtrate extracts from the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas and purified various substances that stimulated gene expression mediated by specific AHL receptor proteins.

Results

Compound purification and identification

Culture filtrate extracts from Chlamydomonas were purified by HPLC and assayed for QS-active compounds as described in Materials & Methods. Bioassay of fractions from the initial HPLC purification revealed the presence of several chromatographically separable substances that specifically stimulated bacterial reporters based on the LasR, AhyR or CepR AHL receptors (Steidle et al., 2001; Winson et al., 1998). These results are consistent with the previous study of QS-active compounds produced by Chlamydomonas (Teplitski et al., 2004). No LuxR agonists were detected. Except for the LasR agonist activity eluting between 16-22 min in the initial fractionation and 13-16 min in the second fractionation, attempts to identify other QS-active substances were unsuccessful.

Material from the peak of LasR agonist activity eluting in methanol at 39 min in the final purification step was pale, metallic yellow in solution and in dry samples. This material was poorly soluble in water, acetonitrile and methanol. It appeared to be increasingly solubilized during elution in the final acetonitrile gradient between 31-49 min. MS analyses of this material showed an apparent molecular ion (M-H) of m/z 241.6, which fragmented in MS/MS experiments to produce a secondary ion of m/z 198.1. Proton NMR measurements recorded clear, readily quantified singlet peaks (δH, ppm) at 7.94 (1H), 7.75 (1H), 2.54 (3H), and 2.52 (3H). UV-visible spectra in acetonitrile showed peaks at 220, 247, 258, 332, and 380 nm. These results are identical to or consistent with those reported previously by this lab (Phillips et al., 1999) and others (Brown et al., 1972; Glebova et al., 1977) for the compound lumichrome, and are consistent with data from parallel measurements here using authentic lumichrome. The structures of lumichrome and its parent, the vitamin riboflavin, are illustrated in Fig. 1A.

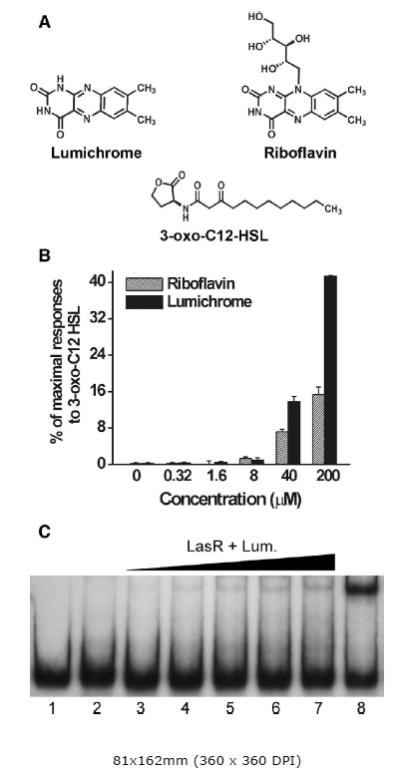

Figure 1. LasR-dependent responses to lumichrome, riboflavin and 3-oxo-C12-HSL.

Structures of lumichrome, riboflavin and 3-oxo-C12-HSL (A). Responses of E. coli JM109 pSB1075 to dried samples of the compounds (B). Aliquots of riboflavin and lumichrome in methanol were dried in microtiter plate wells, mixed with the reporter, and bioassayed as described in Materials & Methods. Results are averages (+/− SE) from triplicate samples from a representative experiment. LasR-PlasI gel shift (C). Radiolabeled DNA containing the lasI promoter was incubated with E. coli lysates containing LasR which were prepared in the presence of either 20 μM lumichrome, 5 μM 3-oxo-C12-HSL, or in the absence of signal. DNA-protein complexes were separated from unbound DNA by electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. Radiolabeled DNA was incubated with: lane 1, no lysate; lane 2, lysate containing LasR (10 μg total protein); lanes 3-7, lysate containing LasR and lumichrome (4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 μg total protein, respectively); and lane 8, lysate containing LasR and 3-oxo-C12-HSL (10 μg total protein). Results are representative of two independent experiments.

LasR is stimulated by authentic lumichrome and riboflavin

The E. coli JM109 pSB1075 lasR,PlasI-luxCDABE AHL reporter (Winson et al., 1998) responded reproducibly to dried samples of authentic riboflavin and lumichrome (Fig. 1B), confirming the identification of lumichrome as a LasR agonist and establishing that riboflavin is a comparably effective agonist. Maximal luminescence responses of the reporter to exogenous riboflavin and lumichrome were about 15-40% of the maximal responses obtained with 3-oxo-C12-HSL, the cognate AHL for LasR. When the parallel E. coli reporters, pSB401 (LuxR) and pSB536 (AhyR), were tested under the same conditions, neither reporter was activated appreciably by riboflavin or lumichrome (data not shown). Thus, the stimulation of luxCDABE expression by riboflavin and lumichrome appeared to be specific for the LasR receptor. In these initial assays, methanol suspensions of lumichrome and riboflavin were dried in microtiter plate wells prior to adding the reporter bacteria, similar to the bioassay of dried HPLC fractions from Chlamydomonas. The strongest responses to riboflavin and lumichrome were observed when the E. coli pSB1075 reporter bacteria were exposed to an amount of the compound that would generate a concentration of 200 μM if it all dissolved. However, the maximum solubility of lumichrome in water or culture medium is only about 20 μM, and the particles dissolve slowly. This suggests that perhaps only a small, unknown fraction of the added lumichrome dissolved and was accumulated by the E. coli reporter during the assays.

Responses to riboflavin and lumichrome depend on the AHL binding domain of LasR

To test for possible indirect effects of riboflavin and lumichrome on stimulation of the E. coli pSB1075 lasR,PlasI-luxCDABE reporter, control constructs were made that lacked the lasR gene or its AHL binding domain, but retained either the lasI promoter or the lasR promoter. In the absence of the lasR gene or the AHL-binding domain of LasR (pTIM5319), riboflavin, lumichrome and 3-oxo-C12-HSL failed to stimulate either the PlasI-luxCDABE or the PlasR-luxCDABE construct in E. coli JM109 (data not shown). Introduction of a full-length copy of lasR on a low copy number plasmid (pTIM5211) restored responsiveness of the PlasI-luxCDABE construct (pTIM505) to these compounds (data not shown), indicating that luminescence responses to riboflavin and lumichrome in the reporter were fully dependent on the LasR protein. It thus seemed likely that riboflavin and lumichrome, like 3-oxo-C12-HSL, interact directly with the LasR protein to activate lux gene expression in the reporter. This conclusion was tested further by electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Lumichrome-activated LasR binds to the lasI promoter region

The ability of exogenously supplied lumichrome to activate the LasR receptor for in vitro binding to the lasI promoter was tested essentially as described by Wade et al. (2005). LasR expressed in E. coli DH5α cells cultured in the presence of 20 μM lumichrome induced a shift in a modest fraction of the band of labeled lasI promoter DNA (Figure 1C), indicating that lumichrome is able to induce LasR to bind PlasI DNA. The intensity of the band was approximately 5% of that obtained in parallel experiments with comparable amounts of protein isolated from cells exposed to 5 μM 3-oxo-C12-HSL. The low band intensity may reflect poor entry of lumichrome into DH5α cells and/or lower binding affinity.

Riboflavin and lumichrome elicit responses in both lasI and rsaL reporter fusions

The pSB1075 bioluminescence reporter used for the previous bioassays is very sensitive. However, the lasI promoter region that was originally fused to the luxCDABE genes in this reporter also included the rsaL promoter and the rsaL coding sequence (Winson et al., 1998). In P. aeruginosa, where LasR is normally produced, rsaL and lasI are divergently transcribed from the same intergenic region (de Kievit et al., 1999) (Fig. 2A). Both genes are regulated by LasR, with rsaL normally expressed at higher population densities (3-oxo-C12-HSL concentrations) than lasI. Biologically, the consequences of activating lasI and rsaL are opposite. LasR-mediated induction of lasI expression increases levels of the LasI AHL synthase, leading to enhanced production of 3-oxo-C12-HSL and amplified expression of the LasR regulon. In contrast, LasR-mediated induction of rsaL leads to synthesis of the RsaL protein which acts as a negative regulator of lasI by binding to the lasI promoter (Rampioni et al., 2006). In assays with the pSB1075 reporter, maximal luminescence responses to 3-oxo-C12-HSL can be reduced about 100 fold by RsaL-mediated inhibition (data not shown).

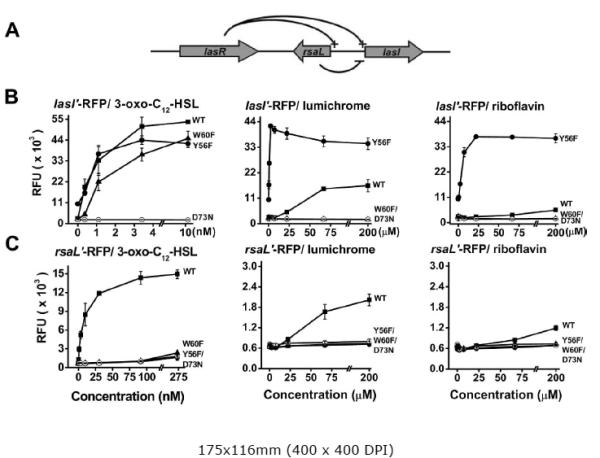

Figure 2. PlasI-rfp and PrsaL-rfp reporter responses to 3-oxo-C12-HSL, lumichrome and riboflavin.

LasR in P. aeruginosa activates the lasI and rsaL promoters while RsaL blocks the lasI promoter (A). E. coli BSV11 ribB::Tn5 strains carrying either PlasI-rfp reporter plasmids (B) or PrsaL-rfp reporter plasmids (C) were tested for responses to dried samples of 3-oxo-C12-HSL, lumichrome and riboflavin as described in Materials & Methods. Each RFP reporter plasmid carries a copy of the lasR gene encoding either the normal LasR receptor (WT) or a LasR receptor with the D73N, W60F, or Y56F amino acid substitution. Responses in relative fluorescence units (RFU) are averages (+/− SE) from triplicate samples for a representative experiment.

Two red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporter plasmids were constructed in order to avoid RsaL-mediated inhibition and to separate the lasI and rsaL promoters from each other. Both the pSRLR (= lasRPlasI-rfp) and pLRTD (= lasRPrsaL-rfp) reporters showed significantly enhanced accumulation of RFP in response to 3-oxo-C12-HSL, riboflavin and lumichrome when tested in the E. coli BSV11 ribB mutant (Fig. 2B and C). Responses of these reporters to riboflavin and lumichrome were several times higher in the E. coli BSV11 ribB mutant, a riboflavin auxotroph, than in the JM109 background (data not shown). Based on RFP accumulation, the lasI promoter was induced more strongly by 3-oxo-C12-HSL than the rsaL promoter, and, as expected, it was induced at lower AHL concentrations (Fig. 2B, C). Maximal lasI activation by 3-oxo-C12-HSL was about 4 times higher than maximal activation by lumichrome (Fig. 2B), whereas maximal rsaL activation by 3-oxo-C12-HSL was about 7.5 times higher than maximal activation by lumichrome (Fig. 2C). While these differences are not large, they were consistent and seem potentially interesting.

To test whether or not lumichrome and riboflavin interact with the same part of the AHL binding domain as 3-oxo-C12-HSL, we also constructed RFP reporters parallel to pSRLR and pLRTD that had single amino acid substitutions in residues Y56, W60, and D73 of the LasR receptor protein. These amino acid residues are highly conserved in the LuxR family of AHL receptors. Based on the crystallographic structure of the homologous TraR receptor (Vannini et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002) and amino acid substitution studies in LuxR (Koch et al., 2005), amino acid residues Y56, W60, and D73 were likely to be involved in hydrogen bonding of LasR to the 1-carbonyl, the ring carbonyl, and the NH group, respectively, of AHL QS signals. These roles are in agreement with the recent crystallographic structure of LasR bound to 3-oxo-C12-HSL (Bottomley et al., 2007).

The D73N amino acid substitution in LasR reduced accumulation of RFP in response to both lumichrome and riboflavin to below detectable limits with the pSRLR (PlasI) reporter as well as the pLRTD (PrsaL) reporter (Fig. 2B,C). The D73N substitution also greatly reduced maximal responses to 3-oxo-C12-HSL for the rsaL reporter (Fig. 2C) and required 50-100 fold higher concentrations of 3-oxo-C12-HSL for maximal activation of the lasI reporter (data not shown). The aspartate residue at position 73 thus appears to be crucial to the activation of LasR by 3-oxo-C12-HSL, riboflavin, and lumichrome for induced expression of both lasI and rsaL.

The W60F substitution in LasR modestly affected responses of the PlasI-rfp reporter to 3-oxo-C12-HSL, shifting them to concentrations roughly 3-fold higher than for the WT LasR receptor (Fig. 2B). However, the W60F substitution greatly reduced responses of the PrsaL reporter to 3-oxo-C12-HSL (Fig. 2C). This substitution also reduced the responses of both PlasI-rfp and PrsaL reporters to riboflavin/lumichrome to below detectable limits (Fig. 2B,C). Thus, the tryptophan at position 60 appears to be crucial to the activation of LasR by lumichrome and riboflavin, and this residue is either modestly or strongly important to activation of LasR by 3-oxo-C12-HSL, depending on the promoter tested.

The Y56F substitution resulted in high background expression of the PlasI-rfp reporter (Fig. 2B), but not the PrsaL-rfp reporter (Fig. 2C). The Y56F substitution had relatively little effect on responses of the lasI reporter to 3-oxo-C12-HSL (Fig. 2B). In contrast, it substantially reduced responses of the rsaL reporter to the AHL (Fig. 2C). Thus, as with the W60F substitution, the effects of the Y56F substitution on activation by 3-oxo-C12-HSL depends strongly on the promoter tested. These findings may provide some insight into the evolutionary constraints on LasR structure in relation to the relative activation of specific promoters.

Unexpectedly, the PlasI-rfp reporter with the Y56F substitution in LasR responded much more strongly to added riboflavin and lumichrome than the reporter with wildtype LasR (Fig. 2B). For example, exposure to 2.5 μM lumichrome induced the Y56F LasR PlasI-rfp reporter to maximum levels whereas the WT LasR reporter was not detectably stimulated by this concentration of exogenous lumichrome (Fig. 2B). It appears that the Y56F substitution may selectively enhance lumichrome/riboflavin binding or activation of the receptor for lasI expression without greatly affecting lasI induction by 3-oxo-C12-HSL. In contrast, the Y56F substitution substantially reduced the ability of 3-oxo-C12-HSL as well as riboflavin and lumichrome to stimulate expression of the PrsaL reporter (Fig. 2C). These opposing effects of the Y56F substitution on lumichrome/riboflavin activation of the two promoters cannot be explained by substitution-altered stability of the LasR protein, nor can altered protein stability explain the promoter-dependent effects of the W60F substitution. The D73N substitution in LuxR abolished responses to its cognate AHL without significantly affecting the stability of the LuxR protein (Koch et al., 2005).

In silico modeling of riboflavin/lumichrome interactions with LasR

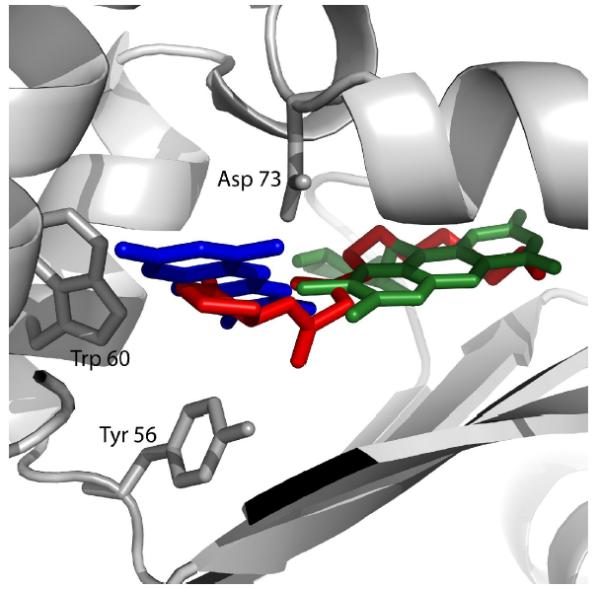

Computer docking analyses indicate that both riboflavin and lumichrome occupy the same binding pocket of LasR as 3-oxo-C12-HSL (Fig. 3), consistent with their identification as LasR agonists based on bioassays and amino acid substitution studies. The docking space occupied by 3-oxo-C12-HSL overlaps the spaces where lumichrome and riboflavin appear to bind, but lumichrome docked in a different space than riboflavin, perhaps due to steric hindrance of the ribityl group. A synthetic triphenyl compound was recently found to activate expression of an rsaL-yfp fusion and to dock with LasR in essentially the same binding pocket as the AHL (Muh et al., 2006b), in agreement with the notion that LasR is able to recognize both AHLs and structurally dissimilar compounds.

Figure 3. Docking of 3-oxo-C12-HSL, lumichrome and riboflavin in the AHL binding pocket of LasR.

The locations of docked ligands and amino acids D73, W60 and Y56 are shown in a ribbon illustration of the AHL binding pocket region of the LasR protein. Lumichrome (blue), riboflavin (green) were docked with LasR independently as described in Materials & Methods, but are shown superimposed with the location of 3-oxo-C12-HSL (red) as determined from the crystal structure of LasR (Bottomley et al., 2007).

Discussion

The Delisea furanones were the first eukaryotic antagonists of bacterial QS to be chemically identified. Lumichrome appears to be the first metabolite from a eukaryote identified as a bacterial QS agonist. While antagonists of QS have been the primary focus of recent studies, compounds that stimulate QS merit interest for several reasons. Chemically, as exemplified by lumichrome, agonists may include new classes of QS-active compounds, distinct from known QS signals or antagonists. Biologically, agonists produced by host organisms may prove to be as important as antagonists in manipulating bacterial QS regulation. For example, QS agonists from a host might serve to initiate specific, mutually beneficial changes in QS-regulated gene expression in symbiotic bacteria. QS agonists could also protect host organisms from pathogens by prematurely inducing QS-regulated virulence gene expression in pre-quorate populations, leading to activation of host defenses before the pathogens are able to infect or damage the host. QS agonists could also have diverse and unexpected effects on QS regulation in host-associated bacteria beyond the simple stimulatory effects suggested by assays with a specific reporter. For example, another purified LasR agonist from Chlamydomonas affected QS in wild type Sinorhizobium meliloti not only as an agonist, but also as an antagonist, synergist, and canceller of different AHL-inducible changes in protein accumulation (Teplitski et al., 2004).

The halogenated furanones previously identified as antagonists of AHL-mediated QS are structurally rather similar to AHLs (Givskov et al., 1996). Thus, it is not surprising that both the furanones and AHLs interact directly with AHL receptor proteins (Koch et al., 2005). Lumichrome, however, has very little structural similarity to AHLs (Fig. 1A). Its identification as a compound capable of stimulating the LasR AHL receptor was therefore quite unexpected. The possibility that AHL receptors might recognize more than one kind of compound was suggested earlier (Holden et al., 1999) based on AHL receptor-mediated responses in bacteria to cyclic dipeptides. The effects of cyclic dipeptides on QS regulation were originally regarded as fortuitous “cross-talk” because millimolar cyclic dipeptide concentrations were required to elicit responses. The discovery that lumichrome/riboflavin can activate specific AHL receptors suggests the need to reexamine cyclic dipeptides as potential in vivo QS signals or mimics.

It is not clear whether the LasR receptor of P. aeruginosa is unique in its ability to be activated by lumichrome and riboflavin. P. putida, a common rhizosphere inhabitant, for example, has a QS AHL synthase, receptor and regulator very similar to LasI, LasR and Rsal in P. aeruginosa (Bertani et al., 2007), and this QS system plays an important role in regulating biofilms (Arevalo-Ferro et al., 2005). Lumichrome and riboflavin did not act as agonists of the LuxR or AhyR reporters. Receptors such as LuxR and AhyR may prove to recognize other classes of bacterial metabolites in addition to AHLs. For example, recent studies indicate that SdiA, the AHL receptor of E. coli (Ahmer, 2004), might interact with the common metabolite indole as well as AHLs to regulate biofilm formation (Lee et al., 2007).

The identification of a vitamin and a vitamin derivative as QS-active compounds is new and unexpected. It raises interest in learning more about the factors that control the synthesis, secretion and uptake of riboflavin, lumichrome and perhaps other vitamins in bacteria. It also raises the question of whether riboflavin and lumichrome might serve as QS signals in bacteria, perhaps ancestral to other QS signals. Many bacteria are known to secrete riboflavin and/or lumichrome (Bacher et al., 2000; Phillips et al., 2000). In view of such possibilities, it is important to recognize that our present work provides no direct evidence that riboflavin or lumichrome actually serve as natural QS signals, mimics or regulators in bacteria. Future studies to explore these possibilities face some important technical limitations. Unlike AHLs, riboflavin and lumichrome do not appear to exchange freely across bacteria cell membranes. No transport systems have yet been identified in any bacterium possessing AHL receptors that might serve to facilitate riboflavin/lumichrome uptake. Nor has the gene encoding a lumichrome synthase been identified in any organism, even though older reports describe the isolation and partial characterization of lumichrome synthases (riboflavin hydrolases) from both plants and bacteria (Foster and Yanagita, 1956; Kumar and Vaidyanathan, 1964; Yang and McCormick, 1967). Nor can the synthesis of riboflavin be manipulated without risking significant effects on metabolic functions other than QS. At present, these factors make it difficult to rigorously analyze QS-related responses to either endogenous or exogenous riboflavin/lumichrome. In P. aeruginosa, for example, the addition of 10 μM lumichrome stimulated a PlasI-rfp reporter 2 fold over background, comparable to maximal 3 to 4 fold stimulation of the promoter by 3-oxo-C12-HSL, but this stimulation was seen only when the promoter was mutated to reduce RsaL binding and when lasR was provided on a multicopy plasmid (data not shown). Thus, the observed responses do not establish whether lumichrome plays a significant role in normal P. aeruginosa QS.

Lumichrome and riboflavin have signal-level effects in various organisms that are independent of QS, effects that help provide a context for understanding their potential QS-related roles. In earlier studies, lumichrome was purified and identified from culture filtrates of Sinorhizobium meliloti as a compound responsible for stimulating root respiration and plant growth in its symbiotic partner, alfalfa (Phillips et al., 1999). Subsequent studies have shown that exposure to 5 nM lumichrome significantly stimulates seedling development in both legume and cereal crops (Matiru and Dakora, 2005a; Matiru and Dakora, 2005b), and triggers diverse changes in gene expression in Arabidopsis (Fox, Bauer and Phillips, unpublished). Application of 10 nM lumichrome to roots also reduced stomatal conductance in bean (Joseph and Phillips, 2003) while application of micromolar lumichrome enhanced photosynthesis in corn and soybean (Khan et al., 2008). These responses suggest that lumichrome has important regulatory roles in plants. Lumichrome was also identified as an inducer of ascidian larval settllment and metamorphosis (Tsukamoto et al., 1999), indicating that it may serve as a developmental signal in animals as well as plants. In plants, there are also hints that riboflavin, or the riboflavin synthesis pathway, has roles in plant signal transduction. Foliar application of riboflavin elicited systemic pathogen resistance in both tobacco and Arabidopsis via specific signaling pathways (Dong and Beer, 2000). Disruption of a gene encoding the enzyme required for synthesis of lumazine, the precursor of riboflavin, affected jasmonate-mediated signaling in Arabidopsis, including defense responses (Xiao et al., 2004).

These responses of eukaryotes to exogenous riboflavin and lumichrome suggest that diverse bacteria could benefit by secreting the compounds during host interactions. In turn, plants, fungi and algae could perhaps benefit by secretion of riboflavin and/or lumichrome to manipulate QS in those bacteria with LasR-like receptors.

Materials and Methods

Collection, purification and bioassay of QS-active compounds from Chlamydomonas

C. reinhardtii CC-2137, initially isolated from soil, was grown in the light on acetate-containing TAP mineral medium (Harris, 1989). Culture filtrates were obtained by centrifugation and passage through glass fiber filters and then subjected to solid phase extraction in 20 L batches passed through 10 g C18 columns (Megabond Elute, Varian) in reverse phase mode. After rinsing with water, the columns were eluted first with 35 mL methanol and then with 35 mL acetonitrile. The two solvent eluates were dried under nitrogen and stored at − 20 C. The compounds were solubilized in 1:1 acetonitrile:water and fractionated in three initial stages on a Waters HPLC employing a model 996 photodiode array detector and two model 510 pumps controlled by Millenium software. Stage I involved injecting 10-L culture equivalents in 10 individual cycles on a semi-preparative HPLC column (Alltech Hypersil C18, 199 × 10 mm), which had been equilibrated in acetonitrile:water (1:9). This column was eluted at 2 mL/min with acetonitrile:water (1:9) for 5 min, followed by a gradient of 10 to 100% acetonitrile from 5-25 min, and then with 100% acetonitrile from 25-50 min. Aliquots of the HPLC fractions were bioassayed with the E. coli pSB1075 LasR, pSB401 LuxR, pSB536 AhyR (Winson et al., 1998) and Pseudomonas putida CepR (Steidle et al., 2001) AHL reporter strains as previously described (Gao et al., 2005; Teplitski et al., 2004), testing for either direct activation of the reporters by compounds from the alga or for inhibition of reporter responses to added AHLs by algal substances. Reporter luminescence or GFP fluorescence were measured with a microtiter plate reader at 37°C or 30°C, for E. coli and P. putida reporters respectively, 3 to 8 h after addition of the reporter suspension to aliquots of the HPLC fractions dried under vacuum in the wells. Aliquots of active fractions were retested to confirm activity and only those activities at least 3-fold above reporter-only controls were considered significant. No compounds with significant agonist or antagonist activities were detected with any of the AHL reporters in fractions from the acetonitrile washes of the solid phase extraction columns, indicating that the initial elution with methanol eluted essentially all of the absorbed QS-active compounds detectable with these reporters.

Further purification of QS-active algal substances focused on one compound capable of stimulating the pSB1075 LasR reporter that eluted between 16 and 22 min during Stage I purification. Pooled active fractions 16-22 obtained from 9 additional runs equivalent to the first were freeze-dried. In Stage 2, the freeze-dried material from Stage 1 was solubilized in acetonitrile:water (1:1) and applied in four separate runs to the same column equilibrated in acetonitrile:water (1:9). This was eluted at 2 mL/min using acetonitrile:water (1:9) for 0-5 min, followed by a gradient of 10 to 30% acetonitrile for 5-85 min, and 30 to 60% acetonitrile for 85-100 min. The LasR stimulatory activity eluted between 13 and 16 min under these conditions. Samples from the four duplicate runs were combined and lyophilized. In Stage 3, the active material was solubilized in acetonitrile:water (1:3) and fractionated on the same column equilibrated with acetonitrile:water (1:9) and eluted at 2 mL/min using acetonitrile:water (1:9) for 0-5 min, followed by a gradient of 10 to 40% acetonitrile for 5-85 min and 100% acetonitrile for 85-100 min. Large amounts of diverse compounds were still evident by UV absorbance across most of elution profile in this separation, but a clear peak of absorbance and LasR stimulatory activity was present at 48-49 min. Material present in this peak was lyophilized and rerun under the same conditions, producing a broad peak of material that was spectrally uniform in the range of 200 to 400 nm and had LasR stimulatory activity proportional to the absorbance. This broad peak of activity started to elute at 31 min and reached a maximum at 49 min. Final HPLC purification was achieved by pooling the active fractions, drying, dissolving in 1:1 methanol:water and running them on an analytical column equilibrated in methanol:water (1:9) and eluted at 1 mL/min with a gradient of 10 to 100% methanol from 5 to 55 min. Under these conditions a sharp, symmetrical, spectrally uniform (240-400 nm) peak with LasR stimulatory activity eluted with maximum absorbance and activity at 39.7 min. Material in this peak was used for UV-visible, mass spectrometric, and NMR analyses. MS data were obtained at the UCD Advanced Instrumentation Facility on a Finnigan LC-ion-trap MS, model LC-Q, using negative mode electrospray ionization after injecting samples in methanol:water (1:1). Tandem MS-MS or MS-MS-MS experiments were conducted by increasing the translational energy of the selected ion and then detecting the major daughter ions. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) analyses were conducted at the UCD NMR Facility with a 600-MHz Bruker Avance DRX-600 operating on XWINNMR software 2.1. Tetramethylsilane was added as an internal standard to the deuterated methanol solvent.

Bioassay of responses to riboflavin and lumichrome

E. coli strains carrying AHL reporter plasmids were taken from glycerol stocks and shake-cultured at 37°C overnight in M9 medium (Meade and Signer, 1977) containing 1% tryptone and the appropriate antibiotic. The cultures were diluted 20-fold into fresh medium, subcultured for 1-2 h, then diluted 10-fold into fresh medium. Triplicate 100 μL portions were dispensed into black microtiter plate wells containing dried samples of 3-oxo-C12-HSL, riboflavin or lumichrome from methanol solutions or suspensions. Plates were incubated at 37°C and luminescence was measured 4 to 8 h later for lux reporters. Fluorescence was measured after 16 to 48 h for RFP reporters. The E. coli BSV11 ribB::Tn5 mutant was obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center, Yale University. Bioassays with reporter plasmids in this mutant were conducted with 500 nM riboflavin in the medium.

Construction of las control plasmids

Primers used to construct the PlasI-luxCDABE and PlasR-luxCDABE control reporters pTIM505, pTIM84 and pTIM5319 are listed in Table 1. pTIM84, a PlasR-luxCDABE reporter was constructed by amplifying the lasR promoter with BA1404 and BA1415 using pSB1075 as a template. The product was then cloned upstream of the promoterless luxCDABE cassette in pSB377 (Winson et al., 1998). pTIM505 consists of just the lasI’ promoter amplified from pSB1075 with BA1403 and BA439 and cloned upstream of the luxCDABE cassette. To confirm that the lasI promoter cloned in pTIM505 was functional, the full length lasR was supplied in trans on pTIM5211. The resulting reporter JM109 pTIM505 pTIM5211 was fully responsive to 3-oxo-C12-HSL. pTIM5211 was constructed by Pfu polymerase-catalyzed PCR amplification of the full length lasR with its own promoter using BA1404 and BA1407. The resulting fragment was cloned into pWSK129. The pTIM5319 control plasmid is a chimeric construct identical to pSB1075 but lacks sequences for the AHL-binding domain of LasR. To construct pTIM5319, the lasR promoter and the codons corresponding to the first five amino acids of the protein were PCR amplified with BA1404 and BA1415, the remainder of the gene and the downstream lasI promoter were amplified with BA1403 and BA439 using pSB1075 as template. The resulting 387 and 676-bp products were gel purified, in vitro phosphorylated with T4 PNK polynucleotide kinase, and the reaction products were then purified, ethanol-precipitated and ligated overnight with T4 HC ligase. The ligation reaction was used as a template for a Pfu-catalyzed PCR amplification using primers BA1404 and BA439. The resulting 1053-bp fragment was gel-purified, cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO® from which it was excised with EcoRI, gel purified and ligated into EcoRI, CIAP-treated pSB377. The resulting constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Table 1.

| Primer | Sequence | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BA439 | CACTAACGTCCCAGCCTTTGCGC TC |

binds at nt. 1559362 of PAO1 genome AE004091 within lasI |

(Winson et al., 1998) |

| BA1403 | TTCTCTCGTGTGAAGCCATTGCTC TGAT |

binds at nt. 1559104 of AE004091 upstream of the lasI promoter |

This study |

| BA1404 | GCGTGGCGATGGGCCGACAGTG | binds at nt. 1557820 of AE004091, upstream of the lasR promoter |

(Winson et al., 1998) |

| BA1407 | ACCTGAGAGGCAAGATCAGAGA GTAAT |

binds at nt.1558905, downstream from lasR |

This study |

| BA1415 | GCGTTCCAGCTCAAGAAAACCGT C |

binds at nt. 1558206 of AE004061 within lasR |

This study |

| 5’RFP | ACAAGCTTAGCTAAGGAGATCTA AATATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG A |

5’ tdRFP primer with in-frame three translational stops, T7genel0 SD and Hind III |

This study |

| 3’RFP | TCTAGATTACTTGTACAGCTCGTC CATGCCGTA |

3’ tdRFP primer with in-frame translational stop and Xba I |

This study |

| 5’LasR | CAGGTACCGCGTGGCGATGGGCC GAC |

5’ LasR primer with Kpn I, binds at nt. 1557817 of AE004091 |

This study |

| 3’LasR-l | CGGACGTCTCAGAGAGTAATAAG ACCCAAATTAACGGCCATAATG |

3’ LasR primer with Aat II binds at nt. 1558893 of AE004091 |

This study |

| 3’LasR−2 | CGGGGCCCTCAGAGAGTAATAAG ACCCAAATTAACGGCCATAATG |

Similar to 3’LasR−1 with Aap I site instead of Aat II |

This study |

| 5’PrLasI | GCGGATCCCGGACGTTTCTTC GAGCCTAGCAAGG |

5’ promoter LasI primer with BamHI site, binds at nt. 1559133 of AE004091 |

This study |

| 3’PrLasI | GCAAGCTTCGATCATCTTCACTTC CTCCAAATAGGAAGCTG |

3’ promoter LasI with Hind III site, binds at nt. 1559263 of AE004091 |

This study |

| 5’LasRY56F | GCCTTCATCGTCGGCAACTTTCC GGCAGCCTGGCGC |

Used with 3’ complementary primer for creating Y56F QuikChangeTM mutagenesis (Stratagene) in LasR. |

This study |

| 5’LasRW60F | GCAACTACCCGGCAGCCTTTCGC GAGCATTACGACCG |

Used with 3’ complementary primer for creating W60F QuikChangeTM mutagenesis (Stratagene) in LasR. |

This study |

| 5’LasRD73N | GCTACGCGCGGGTCAATCCGACG GTCAGTCACTGTAC |

Used with 3’ complementary primer for creating D73N QuikChangeTM mutagenesis (Stratagene) in LasR. |

This study |

Construction of RFP reporter plasmids and LasR amino acid substitution mutants

The PlasI-rfp and PrsaL-rfp plasmids pSRLR and pLRTD were constructed as derivatives of the rasL-yfp plasmid pUM15 (Muh et al., 2006a). The synthetic RFP designated tdTomato (Shaner et al., 2004) was used to replace YFP in pUM15 in order to avoid the strong fluorescence of riboflavin and lumichrome. The tdTomato gene was amplified using primers 5’RFP and 3’RFP (Table 1) using pCR2.1v-tdTomato (Shaner et al., 2004) as template. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and XbaI and then cloned into pUC19. The resulting plasmid was digested with HindIII/ScaI and used to replace YFP in pUM15, thus creating the rsaL’-tdTomato reporter designated pTD. To create the pLRTD (lasR,PrsaL-tdTomato) reporter plasmid, the lasR gene was amplified from template pSB1075 (Winson et al., 1998) with 5’LasR and 3’LasR-1. The lasR PCR product and vector pTD were digested with KpnI, AatII and ligated to create pLRTD. The PlasI-rfp reporter plasmid pSR and the lasR, PlasI-rfp reporter plasmid pSRLR were created by first cloning the lasI promoter (PlasI) into the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1MCS5 (Kovach et al., 1995). PlasI was PCR amplified with 5’PrLasI and 3’PrLasI using pSB1075 as a template. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and HindIII and cloned into pBBR1MCS5 making pBBR1MCS5-PlasI. To create a PlasI-tdTomato fusion, the tdTomato-lasR cassette in pLRTD was PCR amplified with 5’RFP and 3’LasR-2, then digested with HindIII and ApaI and cloned downstream of PlasI in pBBR1MCS5-PlasI, creating pBRC12. The pBRC12 construct was digested with BamHI to release the PlasI -tdTomato cassette, which was then used to replace the PrsaL-tdTomato cassette in the pTD and pLRTD plasmids. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Site-directed mutations in lasR were created using the plasmids pSRLR and pLRTD as templates using the QuikChange™ XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as detailed in the users manual. The substitution mutants were confirmed by sequencing.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

Experiments were conducted essentially as described (Wade et al., 2005) with LasR overproduced in E. coli cultures exposed to either 5 μM 3-oxo-C12-HSL or 20 μM lumichrome. Overnight cultures of E. coli strain DH5α carrying either plasmid pECP8 (Ptac-lasR) or vector plasmid pEX1.8 (Pearson et al., 1997) were subcultured to an optical density of 0.05 at 600 nm into LB medium buffered with 50 mM MOPS, and supplemented with either 5 μM 3-oxo-C12-HSL or 20 μM lumichrome. Subcultures were grown at 37°C with shaking for 3 hours, and then isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mM to induce expression of LasR. Cultures were then incubated another 2 hours, after which the cells were harvested by centrifugation. Lysates were prepared by passing the cells through a French pressure cell at 16,000 psi. The total protein concentration of lysates was determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). A 241 bp DNA fragment containing the lasI promoter region was amplified by PCR using primers 5’-TTTTGGGGCTGTGTTCTCTC-3’ and 5’-CACTTGAGCACGCAACTTGT-3’, and P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 chromosomal DNA as template. DNA fragments were radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin-Elmer) by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen). DNA binding reactions were carried out in the buffer described by Wade et al (Wade et al., 2005). Each binding reaction contained radiolabeled DNA equivalent to approximately 6 × 104 cpm, 0.5 μg salmon sperm DNA, and lysate containing 0 to 20 μg protein. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes and then separated on a native 6% polyacrylamide gel. Radiolabeled fragments were visualized by autoradiography after 2 d exposure of X-ray film. All binding reactions containing E. coli lysate, both with and without LasR present and regardless of the presence or absence of signal, caused a shift in the mobility of the radiolabeled lasI promoter fragment (data not shown). The mobility shift created by LasR in combination with either lumichrome or 3-oxo-C12-HSL was clearly distinct from the shift caused by E. coli lysate alone.

Lumichrome and Riboflavin Docking

The x-ray crystal structure coordinates of the LasR protein and ligands were obtained from the protein data bank: LasR - pdb id 2UV0, 3-oxo-C12-HSL - pdb id 2UV0, lumichrome - pdb id 2CC7 and riboflavin - pdb id 1BU5. Dockings of lumichrome and riboflavin with LasR were carried out independently, with docking of 3-oxo-C12-HSL as a control, using ZDOCK (Chen and Weng, 2002) in its default global scanning mode.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. J. S deRopp and W. T. Jewell, respectively, for NMR and MS analyses, and Dr. D.R. Cook for generously providing access to a microtiter plate reader. We are also indebted to Dr. Rinku Jain, Malathy Krishnamurthy, Charles Friday, Chris Noriega and Zeeshan Qamar for generous assistance, Deb Hogan for induced culture filtrates, and Roger Tsien for the td Tomato RFP strain. Support was provided by grants from the Ohio Plant Biotechnology Consortium (WDB,JBR), NSF DEB-0120269 (DAP), National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension 2003-01177 (WDB, JBR), NRI 2004-03250 (WDB), NRI 2007-35319-18158 (MT, WDB, JBR), and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease R01-AI076272 (ECP). Partial support for salary and supplies was provided to WDB by the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center. Horticulture & Crop Science manuscript # xxx.

References

- Ahmer BM. Cell-to-cell signalling in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:933–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo-Ferro C, Reil G, Gorg A, Eberl L, Riedel K. Biofilm formation of Pseudomonas putida IsoF: the role of quorum sensing as assessed by proteomics. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2005;28:87–114. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo-Ferro C, Hentzer M, Reil G, Gorg A, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M, Riedel K, Eberl L. Identification of quorum-sensing regulated proteins in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa by proteomics. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:1350–1369. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher A, Eberhardt S, Fischer M, Kis K, Richter G. Biosynthesis of vitamin b2 (riboflavin) Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:153–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Losick R. Bacterially speaking. Cell. 2006;125:237–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani I, Rampioni G, Leoni L, Venturi V. The Pseudomonas putida Lon protease is involved in N-acyl homoserine lactone quorum sensing regulation. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PO, Rasmussen TB, Christophersen L, Calum H, Hentzer M, Hougen HP, Rygaard J, Moser C, Eberl L, Hoiby N, Givskov M. Garlic blocks quorum sensing and promotes rapid clearing of pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Microbiol. 2005;151:3873–80. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley MJ, Muraglia E, Bazzo R, Carfi A. Molecular insights into quorum sensing in the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the structure of the virulence regulator LasR bound to its autoinducer. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13592–600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Hornbeck CL, Cronin JR. Alloxazines and isoalloxazines. Mass spectromteric analysis of riboflavin and related compounds. Organic Mass Spectrometry. 1972;6:1383–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Weng Z. Docking unbound proteins using shape complementarity, desolvation, and electrostatics. Proteins. 2002;47:281–94. doi: 10.1002/prot.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kievit T, Seed PC, Nezezon J, Passador L, Iglewski BH. RsaL, a novel repressor of virulence gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2175–84. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2175-2184.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degrassi G, Devescovi G, Solis R, Steindler L, Venturi V. Oryza sativa rice plants contain molecules that activate different quorum-sensing N-acyl homoserine lactone biosensors and are sensitive to the specific AiiA lactonase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Beer SV. Riboflavin induces disease resistance in plants by activating a novel signal transduction pathway. Phytopathology. 2000;90:801–811. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.8.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong YH, Zhang LH. Quorum sensing and quorum-quenching enzymes. J Microbiol. 2005;43:101–9. Spec No. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JW, Yanagita T. A bacterial riboflavin hydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1956;221:593–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Teplitski M, Robinson JB, Bauer WD. Production of substances by Medicago truncatula that affect bacterial quorum sensing. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16:827–834. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.9.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Chen H, Eberhard A, Gronquist MR, Robinson JB, Rolfe BG, Bauer WD. sinI- and expR-dependent quorum sensing in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7931–44. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.7931-7944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Chen H, Eberhard A, Gronquist MR, Robinson JB, Connolly M, Teplitski M, Rolfe BG, Bauer WD. Effects of AiiA-mediated quorum quenching in Sinorhizobium meliloti on quorum sensing signals, proteome patterns and symbiotic interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:843–856. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-7-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givskov M, Nys R.d., Manefield M, Gram L, Maximilien R, Eberl L, Molin S, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. Eukaryotic interference with homoserine lactone-mediated prokaryotic signalling. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6618–6622. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6618-6622.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glebova GD, Kirillova NI, Berezovskii VN. Investigation in the alloxazine and isoalloxazine series XLVIII. Synthesis and properties of the 5-N-oxides and 5, 10-di-N-oxides of alloxazines. J. Organ. Chem. USSR. 1977;13:996–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Harris EH. The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook. Academic Press; San Diego: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Holden MT, Ram Chhabra S, de Nys R, Stead P, Bainton NJ, Hill PJ, Manefield M, Kumar N, Labatte M, England D, Rice S, Givskov M, Salmond GP, Stewart GS, Bycroft BW, Kjelleberg S, Williams P. Quorum-sensing cross talk: isolation and chemical characterization of cyclic dipeptides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1254–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph CM, Phillips DA. Metabolites from soil bacteria affect plant water relations. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2003;41:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanoli K, Lindow SE. Disruption of N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated cell signaling and iron acquisition in epiphytic bacteria by leaf surface compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7678–86. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01260-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan W, Prithiviraj B, Smith DL. Nod factor [Nod Bj V (C(18:1), MeFuc)] and lumichrome enhance photosynthesis and growth of corn and soybean. J Plant Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch B, Liljefors T, Persson T, Nielsen J, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M. The LuxR receptor: the sites of interaction with quorum-sensing signals and inhibitors. Microbiol. 2005;151:3589–602. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SA, Vaidyanathan CS. Hydrolysis of riboflavin in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;89:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0926-6569(64)90106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Jayaraman A, Wood TK. Indole is an inter-species biofilm signal mediated by SdiA. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manefield M, Rasmussen TB, Henzter M, Andersen JB, Steinberg P, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M. Halogenated furanones inhibit quorum sensing through accelerated LuxR turnover. Microbiol. 2002;148:1119–27. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matiru VN, Dakora FD. The rhizosphere signal molecule lumichrome alters seedling development in both legumes and cereals. New Phytol. 2005a;166:439–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matiru VN, Dakora FD. Xylem transport and shoot accumulation of lumichrome, a newly recognized rhizobial signal, alters root respiration, stomatal conductance, leaf transpiration and photosynthetic rates in legumes and cereals. New Phytol. 2005b;165:847–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade HM, Signer ER. Genetic mapping of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:2076–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.5.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muh U, Schuster M, Heim R, Singh A, Olson ER, Greenberg EP. Novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing inhibitors identified in an ultra-high-throughput screen. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006a;50:3674–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00665-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muh U, Hare BJ, Duerkop BA, Schuster M, Hanzelka BL, Heim R, Olson ER, Greenberg EP. A structurally unrelated mimic of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006b;103:16948–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JP, Pesci EC, Iglewski BH. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5756–67. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5756-5767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson T, Hansen TH, Rasmussen TB, Skinderso ME, Givskov M, Nielsen J. Rational design and synthesis of new quorum-sensing inhibitors derived from acylated homoserine lactones and natural products from garlic. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:253–62. doi: 10.1039/b415761c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DA, Martínez-Romero E, Yang G, Joseph CM. Release of nitrogen: A key trait in selecting bacterial endophytes for agronomically useful nitrogen fixation. In: Ladha PMRJK, editor. The Quest for Nitrogen Fixation in Rice. International Rice Research Institute; Makati City, Philippines: 2000. pp. 205–>217. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DA, Joseph CM, Yang GP, Martínez-Romero E, Sanborn JR, Volpin H. Identification of lumichrome as a Sinorhizobium enhancer of alfalfa root respiration and shoot growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA. 1999;96:12275–12280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampioni G, Bertani I, Zennaro E, Polticelli F, Venturi V, Leoni L. The quorum-sensing negative regulator RsaL of Pseudomonas aeruginosa binds to the lasI promoter. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:815–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.815-819.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen TB, Givskov M. Quorum sensing inhibitors: a bargain of effects. Microbiol. 2006;152:895–904. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel K, Kothe M, Kramer B, Saeb W, Gotschlich A, Ammendola A, Eberl L. Computer-aided design of agents that inhibit the cep quorum-sensing system of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:318–23. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.318-323.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidle A, Sigl K, Schuhegger R, Ihring A, Schmid M, Gantner S, Stoffels M, Riedel K, Givskov M, Hartmann A, Langebartels C, Eberl L. Visualization of N-acylhomoserine lactone-mediated cell-cell communication between bacteria colonizing the tomato rhizosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5761–70. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5761-5770.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitski M, Robinson JB, Bauer WD. Plants secrete substances that mimic bacterial N-acyl homoserine lactone signal activities and affect population density-dependent behaviors in associated bacteria. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:637–648. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitski M, Chen H, Rajamani S, Gao M, Merighi M, Sayre RT, Robinson JB, Rolfe BG, Bauer WD. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii secretes compounds that mimic bacterial signals and interfere with quorum sensing regulation in bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:137–46. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.029918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto S, Kato H, Hirota H, Fusetani N. Lumichrome. A larval metamorphosis-inducing substance in the ascidian Hhalocynthia roretzi. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:785–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini A, Volpari C, Gargioli C, Muraglia E, Cortese R, De Francesco R, Neddermann P, Marco SD. The crystal structure of the quorum sensing protein TraR bound to its autoinducer and target DNA. EMBO J. 2002;21:4393–401. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil ML. DNA microarrays in analysis of quorum sensing: strengths and limitations. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2061–5. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2061-2065.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade DS, Calfee MW, Rocha ER, Ling EA, Engstrom E, Coleman JP, Pesci EC. Regulation of Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4372–80. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4372-4380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winson MK, Swift S, Fish L, Throup JP, Jorgensen F, Chhabra SR, Bycroft BW, Williams P, Stewart GS. Construction and analysis of luxCDABE-based plasmid sensors for investigating N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:185–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Dai L, Liu F, Wang Z, Peng W, Xie D. COS1: an Arabidopsis coronatine insensitive1 suppressor essential for regulation of jasmonate-mediated plant defense and senescence. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1132–42. doi: 10.1105/tpc.020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CS, McCormick DB. Substrate specificity of riboflavin hydrolase from Pseudomonas riboflavina. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;132:511–3. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(67)90171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HB, Wang LH, Zhang LH. Genetic control of quorum-sensing signal turnover in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4638–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022056699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]