Introduction

High-risk sexual behavior – including unprotected sex with overlapping partners– is the second leading contributor to the burden of disease globally, and HIV/AIDS is responsible for a large share of this burden (Ezzati, Lopez, Rodgers, Vander Hoorn, & Murray, 2002). Certain populations, such as individuals who are homeless, are at particular risk for HIV (Robertson, et al., 2004). Unprotected heterosexual contact is a key route of HIV transmission (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008) and men who self-identify as heterosexual make up the majority of homeless populations in large urban areas (Robertson, et al., 2004). While much existing research focuses on condom use, limiting the degree to which men have concurrent partners is critical to reducing HIV transmission (Wenzel, et al., 2012). Research on the sexual behavior and relationships of homeless men identified a general desire for intimacy, honesty, trust, and commitment in relationships on the street (Kennedy, Tucker, Green, Golinelli, & Ewing, 2012; Ryan, et al., 2009). However, actual patterns of sexual behavior in this population frequently involve multiple, overlapping partnerships – often without condom use and without full disclosure of this behavior to partners (Brown, et al., 2012; Wenzel, et al., 2012).

Recent research has hypothesized that men are influenced to engage in risky sex with women – including multiple, overlapping partners - if they internalize traditional gender roles that promote sexual dominance over women (Kaufman, Shefer, Crawford, Simbayi, & Kalichman, 2008). Further, some studies have hypothesized that this may be a key mechanism behind high rates of HIV among economically marginalized men, who may compensate for lack of economic power by exerting sexual power (Dworkin, Fullilove, & Peacock, 2009; Poehlman, 2008). However, previous analyses of data from the current dataset raise questions about whether hyper-masculinity is a useful explanatory mechanism in understanding homeless men’s risky sexual practices. First, a qualitative analysis of men’s notions of sexual risk indicated that men’s calculations of sexual risk were mostly focused on relationships, and that a large percentage of homeless men perceived relationships with women to carry a high emotional risk (Brown, et al., 2012). Second, these results led to a mixed methods investigation of men’s beliefs about gender and relationships, which showed that most homeless men disagreed with hyper-masculine statements about sexual dominance and endorsed gender equality in relationships (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012). Furthermore, studies of other homeless populations have indicated that relationship factors and emotional dynamics within relationships are significant correlates of sexual risk behavior (Kennedy, Tucker, et al., 2012; Kennedy, Wenzel, et al., 2010; Ryan, et al., 2009).

The goal of this study is to better understand the desire for, constraints on, and predictors of different relationship types and associated sexual behaviors among homeless men, with a specific focus on committed, monogamous relationships. We initially collected rich qualitative data (n=30) on homeless men’s gender ideologies and sexual behaviors and then, several months later, collected detailed quantitative data (n=305) on men’s beliefs, sexual partners, social networks, and sexual behaviors. We begin with an analysis of the qualitative data focused on how men view sex and relationships on the street, and how they describe their own approach to sex and relationships. This qualitative analysis builds on a previous mixed methods study (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012). We use items from a principle components analysis in this study (which in turn originated from qualitative data analysis) to produce analytic codes for the present study. Using the results of the qualitative analysis to assist with variable selection and model construction, we then move to a quantitative analysis of the drivers of monogamy on the street that examines the role of variables at the individual, relationship, and social network level.

High risk sexual behavior and relationships among homeless men is a complex problem with interdependencies at multiple causal levels (Tucker, et al., 2012). Choosing the most effective intervention strategy for such complex problems depends upon a detailed, nuanced, and accurate understanding of the multiple causal pathways involved in such behaviors (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008). However, many existing approaches to reducing sexual risk behavior in this population focus on a single causal level. For example, condom promotion interventions focus on the psychological elements of condom knowledge as well as motivation and skills for condom use (Bowen, Williams, McCoy, & McCoy, 2001; Orr, Langefeld, Katz, & Caine, 1996). A focus on single causal levels in efforts to understand or intervene upon risky sexual practices in homeless populations may be missing many of the important causal drivers of risky sex among homeless populations, such as relationship dynamics, the role of the broader social network, and the socioeconomic and structural barriers that constrain the behaviors of homeless populations. Indeed, most health interventions with homeless populations have met with limited success, likely due to the complexity and interrelatedness of the problems faced by this population (Power, et al., 1999; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & Development, 2007).

Properly addressing such complexity and interdependency requires agile research strategies that can not only assess causal factors at multiple levels but also flexibly incorporate new information as it arises during the research process. This means enabling creative and productive conversation between qualitative and quantitative measurement and analytic modalities – a mixed methods approach (Bernardi, Keim, & von der Lippe, 2007; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007). Thus, to explore the drivers of risky sexual behavior among homeless men, the current study draws upon a creative intersection of qualitative and quantitative methodologies, generates inferences via several iterations of hypothesis generation and testing, and is driven by a practical concern with intervening upon risky sex among homeless men. As such, we incorporated elements of three types of mixed methods perspectives –methods-focused, methodological, and pragmatic (Creswell & Tashakkori, 2007).

As should often occur in studies that allow for multiple iterations of hypothesis generation and testing with interlaced qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis, our initial gender-based model was subject to multiple revisions and modifications over time. Multiple rounds of qualitative and quantitative analysis (including multiple iterations of hypothesis generation and testing) moved us away from thinking about gender ideology and hyper-masculinity and towards thinking about gender roles and structural barriers to enacting these roles. We illustrate how this emergent understanding is attentive to variability among homeless men and the diverse narratives of relationships and homeless men’s experiences. Finally, we show how this progression in understanding has produced new suggestions for intervention strategies targeted at core drivers of risky sexual behavior on the street. We conclude with a holistic causal model of the determinants of risky sex and relationships among homeless men, describing patterns of influence at multiple causal levels.

Methods

The core analysis for this study involved a complementary qualitative and quantitative analytic approach focused on types of sexual relationships reported by men living on Skid Row. Below we describe the qualitative and quantitative samples, data collection and measures, and analytic approach.

Qualitative Sample (n=30)

For the qualitative sample, we used a stratified random sample to recruit participants from meal lines and shelters in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles, which is home to one of the largest homeless populations in the U.S. (Lee & Price-Spratlen, 2004). We first developed a list of shelters and meal lines using existing directories of services for homeless individuals and conducting interviews with services providers. We randomly selected six sites including three shelters and three meal lines, stratified by size of shelter and meal served (breakfast, lunch, dinner). Men were randomly selected from sites via a random numbers table. Additional details on sampling can be found elsewhere (Brown, et al., 2012; Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012).

Thirty-six men screened eligible and 30 completed the interview (four men refused to participate and two interviews were broken off midstream; completion rate=83%). Most of the 30 men (n=23, 77%) self-identified as African American, with four identifying as mixed-race, two as White, and one as Asian or Pacific-Islander. Four men indicated that they were Hispanic in a separate ethnicity question. Men ranged in age from 22 to 54 (median=44, mean (SE)=43.7 (± 1.5)), and ranged in time spent homeless in lifetime from two weeks to 16 years (median=4 years; mean (SE)=4.7 years (± .7)).

Interviews lasted approximately 60–90 min, and were audio recorded. All participants knew they were being audio recorded, consented to the interview after reading and listening to a description of the study and its risks and benefits, and were given $25 in cash for participation.

Quantitative Sample (n=305)

For the quantitative sample, we used a stratified probability sample where the meal lines served as the only strata. A list of meal lines was developed through directories of services for homeless individuals and interviews with services providers. We recruited from 13 meal lines (5 breakfasts, 4 lunches and 4 dinners) offered by 5 different organizations. We assigned an overall quota of completed interviews for each site that was approximately proportional to the size of the meal line (number of men served daily) and drew a probability sample of men from the line during a visit. Additional details concerning sampling procedures and weights can be found elsewhere (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012; Tucker, et al., 2012).

Of the 338 men who were initially screened eligible for the structured interview, 320 interviews were completed (18 refusals). Of these 320, 11 were dropped from the study because they either had large amounts of missing data or were break-offs. Four interviews were dropped from the study after we determined that the respondents had already been interviewed for this study (and were technically ineligible at screening). The final sample size was 305, for a completion rate of 91% (305/334). Structured interviews lasted an average of 83 minutes. Participants were given $25 in cash for participation. Human subject protections and data safeguarding procedures were approved by the RAND and University of Southern California Human Subject Protection Committees for both the qualitative and quantitative data collection phases.

Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative interviews collected information about the gender ideology and beliefs of homeless men as well as details about two sexual encounters with women that occurred within the last 6 months. Sexual events were sampled to maximize diversity in risk behaviors (i.e., condom and substance use) and partners, as described elsewhere (Brown, et al., 2012).

Interviews were designed to help create structured survey items for quantitative data collection, and followed a matrix-based semi-structured format, which allows interviewers to cover a list of topics and subtopics according to two intersecting dimensions. Interviewers were allowed to skip around the matrix and to follow up on topics in the order that they naturally arose in the conversation. This allowed interviewers to follow a natural conversational flow, but also provided a mechanism to check off topics as they are covered so as not to miss crucial components of the interview. Further information on the interviewing matrix approach can be found elsewhere (Brown, et al., 2012, Ryan, 2009).

Two different matrices were used during qualitative interviews: a gender matrix and a sexual event matrix. In the gender matrix, the X-axis represented different groups or aspects of society – men, women, homeless men, men of the respondent’s ethnicity, and historical changes. The Y-axis represented different types of behavioral expectations – general expectations, expectations for family-related behaviors, expectations for behaviors in serious relationships, and expectations in casual relationships. Intersections of topic headings along the X- and Y-axes produced specific interview probes. For example, the intersection of “family” and “historical changes” generated the probe, “How have things changed in terms of what is expected of men and women in families?” In the sexual event matrix, the X-axis represented different stages of each of the two sexual events— the background/pre-existing relationship with partner, the period immediately before sex, the sexual event itself, and the period immediately after sex. The Y-axis represented different aspects of the sexual event—the social context, behaviors, thoughts and decisions, emotions and feelings, alcohol or drug use, and condom use.

Quantitative Data Collection

Individual Characteristics

Background characteristics included demographics and mental health status. Demographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, income in the past 30 days, and total months homeless in the respondent’s lifetime. Mental health measures included: (a) 4-item PTSD screener (Prins, et al., 2004) measuring re-experiencing, numbing, avoidance, and hyper-arousal (respondent’s screened positive for PTSD if they answered yes to three or more items); and (b) 5-item measure of mental health-related distress (MHI-5; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) which asks respondents to rate how frequently in the past month they have felt “calm and peaceful”, “downhearted and blue”, “a happy person,” and so forth (1=none of the time to 6=all of the time).

Measures of sexual behaviors and attitudes included whether the respondent identified as heterosexual and number of female sexual partners in the last 6 months. We used four items each to assess negative attitudes towards condoms (Mutchler, et al., 2008), and condom use self-efficacy (Jemmott & Jemmott, 1991). These items were rated on a 4-point scale (1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree), and scale characteristics are described elsewhere (Tucker, et al., 2012). We also asked respondents if they had ever tested positive for HIV.

Gender-related beliefs were assessed with items from a principal components analysis, as described in (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012).. Items assessed a spectrum ranging from high value placed on serious relationships (sample item: “Having a serious relationship on the street is worth the effort”) to relationship avoidance and mistrust of women (sample item: “If you try to have a relationship on the street, she will probably leave you for someone else”).

Using the aggregation of reported characteristics on the entire set of alters in the personal network, we calculated the proportion of alters believed to be homeless and the proportion of non-sex partners believed to engage in risky sexual practices (defined as having had multiple sex partners, had sex with someone they did not know, or not using a condom with a new partner).

Partner, Relationship, and Social Network Characteristics

To characterize sex partners and their position in respondent’s social networks, we followed established procedures for conducting personal network interviews (McCarty, Bernard, Killworth, Shelley, & Johnsen, 1997). Personal networks encompass the ties that surround a single focal individual, in this case, a homeless man (Campbell & Lee, 1991). Personal network interviews are typically divided into three sections: questions designed to generate the names of people in the respondent’s social network (alters), questions about each alter (network composition), and questions about the relationship between each unique pair of network alters (network structure).

To generate alter names, we asked respondents to name, by first name or nickname only, 20 individuals that they knew, who knew them, and with whom they had contact sometime during the past year or so (face-to-face or by phone, mail or e-mail). We then asked respondents if they had named each of their recent female sex partners among the 20 alters; if not, we collected the additional names of up to four sex partners. To characterize the composition of the network, men answered a series of questions about each alter, including their background characteristics, behaviors, and relationship with the respondent.

For these analyses, we focus on the following information men provided on each identified sex partner: (a) whether she had used drugs or drank alcohol to the point of intoxication in the last 6 months; (b) whether she had a job; (c) whether she was homeless; (d) frequency of contact with her in the last 6 months (0=never to 4=daily or almost daily), (e) if he felt emotionally close to her (1=yes, 0=no); and (f) if she had provided him with tangible support (e.g., food, money, clothes, a place to stay) in the last 6 months (1=yes, 0=no). Finally, partner connectedness with the respondent’s network was measured with a variable that was constructed from the network structure data (i.e., whether each alter-alter pair had contact either “sometimes” or “often” in the past year). Specifically, we calculated the partners’ betweenness centrality (Wasserman & Faust, 1994), which is a continuous measure of how often an alter lies on the shortest path between pairs of other alters in the network.

Dependent Variable – Monogamy

The dependent variable in our quantitative analysis was whether each respondent reported having a monogamous relationship with a particular sexual partner. This variable was derived from two questions asked regarding each sexual partner. The first asked whether the respondent had sex with any other partners “around the same time” as sex with that particular partner. Respondents were also asked if they thought the partner was having sex with other partner around the same time period. If answers to both questions were “no,” the relationship was classified as monogamous.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The qualitative analytic component of this study directly draws upon the quantitative output of a cultural consensus analysis focused on gender ideology and beliefs with our Skid Row population-based sample (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012). Cultural consensus analysis (CCA) is a mixed-methods approach to describing and measuring the pattern of agreement within a group regarding a particular cultural domain (Romney, Weller, & Batchelder, 1986; Weller, 2007). Rather than assuming that cultural patterns or beliefs conform to racial-ethnic, social class, or other divisions, CCA is a process for assessing cultural agreement directly.

In the previous study, analysis of semi-structured interviews (n=30) identified themes related to masculinity, relationships, and sexual behavior. Verbatim statements connected with these themes were used in a structured interview with the population-based sample (n=305). Then, the informal consensus analytic model (Weller, 2007) identified patterns of agreement and disagreement regarding these statements among homeless men. Next, principal components analysis was used to identify the predominant axes of agreement and disagreement among homeless men regarding masculinity, relationships, and sexual behavior on the street (Handwerker, 2002). This identified two axes of variation among men: Component 1, concerning the importance of responsibility and equality in relationships (vs. traditional masculinity ideals), and Component 2, concerning the value of long-term relationships (vs. more misogynist and avoidant approaches to relationships).

In the current study, we used the items with the strongest loadings (both negative and positive) on Component 1 and Component 2 with direct relevance to sexual relationships and sexual risk to create five codes for further analysis of semi-structured interviews, which in turn produced five additional emergent themes. The strongest loading items on Components 1 and 2 concerned two major themes – models of relationships and relationship barriers. Topics regarding models of relationships featured: (1) the male role as protector and provider; (2) the perceived ideal state of sharing household tasks in a “50/50” arrangement between man and woman; and (3) women as potential saviors or “cheerleaders” but also sources of men’s downfall. Two additional topics concerning relationship barriers focused on: (4) the struggle and difficulties of relationships on the street; and (5) instability and manipulation in relationships.

We used these five topical areas to code data relating to barriers faced by homeless men who want to have relationships with women, coding all related sections from transcripts using Atlas.ti and organizing output by subject in an Excel spreadsheet (a procedure we also followed for all subsequently described themes). Data coding followed standard methods to identify themes, as described by Ryan & Bernard (2003) and outlined for this particular data set by Brown, et al. (2012).

Directly examining output from these five codes alerted us to a 6th and 7th emergent theme in the data, both focused on barriers to relationships: (6) the lack of access to female partners and how the stigma, low self-esteem, and low social status associated with being a homeless male compounded this problem; and (7) structural and logistical barriers to relationships on Skid Row, including the lack of privacy and safety concerns.

Data on respondents’ two recent sexual events with women and relationships allowed us to examine whether the patterns of behavior that men described as the general modus operandi on the street also played out in their own behavior within sexual relationships. To do this, we created a typology of sexual relationship types based on men’s descriptions of their sexual encounters and details they provided about the nature of their relationships with their partners. We categorized men in terms of the types of relationships they engaged in over the last 6 months and describe condom use for these different types of relationships. The content of men’s descriptions of sexual encounters led us to three additional emergent themes: (8) the opportunistic, unstable nature of most relationships on the street; (9) the idealization of non-monogamous partners; and (10) relationship narratives of committed, monogamous partnerships. In sum, ten themes emerged from the data -- the five original themes identified from Kennedy et al. (2012), and five additional new, emergent themes from the subsequent data analysis. The full list of original and emergent themes for data coding is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Original and Emergent Themes

| Original Themes | Emergent Themes |

|---|---|

| Models of Relationships | Patterns of Relationships and Sex |

| 1. Male as provider and protector | 6. Temporary, unstable relationships |

| 2. Relationships as “50/50” | 7. Idealization of non-monogamous partners |

| 3. Woman as saviors | 8. Monogamy narratives |

| Relationship Barriers | Relationship Barriers - Emergent Themes |

| 4. Difficulties of relationships on the street | 9. Logistical and structural barriers |

| 5. Instability and manipulation in relationships | 10. Lack of access to female partners |

Quantitative Data Analysis: Multi-level Model

Having a large sample with up to four relationships per respondent allowed us to test which characteristics of men, their partners, and relationships predicted monogamous sexual behavior. We analyzed data at two levels, using a multi-level dyadic design (Kennedy, Tucker, et al., 2012; Kennedy, et al., 2010). At the highest level (level 2, individual level), we analyzed variables measuring the men’s demographic characteristics, attitudes about condoms and HIV, gender related attitudes, mental health, and social network composition and structure. At the lowest level (level 1, partner/relationship level) we analyzed variables measuring partner characteristics and characteristics of the relationship between the respondents and their partners. Also at the lowest level is the dependent variable, having a monogamous relationship.

To test which variables had significant associations with monogamy controlling for other variables within and across levels, we built a multivariate, multi-level logistic regression model with a one-to-many personal network design (Gonzalez & Griffin, 2012). We used the gllamm procedure in Stata 10.1 (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992) with a binomial distribution, and a logit link to test associations between the independent and dependent variables. To determine which variables were the best candidates for the final model, we first selected a set of variables based on the results of qualitative data analysis – focused on potential indicators of high vs. low quality partners - in which men described predictors of relationships on the street, complemented by theory and existing studies. We then narrowed this set of variables by running each variable alone in a bivariate model testing for an association with the dependent variable. In the final multivariate model, we included variables associated with the outcome at p < .05 in bivariate analyses.

Results

Qualitative Results

Models of Ideal Relationships

Below, we report the results of using the provider/protector, 50/50, and cheerleader/savior themes to code and analyze data in qualitative interviews. A total of 21 men mentioned the male provider and protector role as highly important in relationships. For example, “You’re supposed to protect your family and protect your loved ones, don’t let any harm or danger come to them,” or ““Be responsible, breadwinner, have a job, take care of the household.” Out of the remaining nine men, three did not bring up this theme during the interview. Four men did not agree with the provider/protector role, saying it put too much pressure on men and put them in an unfair position; “Society puts you in a cage and you can’t escape it.” Finally, two men thought that recent social changes made it possible for the woman to be a provider in relationships. For example, “if she was the breadwinner.…I’ve got to take care of this home front…I know when she comes in she’ll be tired…”

Meanwhile, a total of 22 men described a “50/50” model of sharing household tasks and relationship burden. For example, “…It’s a relationship. It’s equal. They both get equal roles in a relationship.” Of the remaining eight men, four did not mention the 50/50 theme during the interview, and four men were directly opposed to a 50/50 arrangement, seeing it as potentially endangering male status. For example, “the more rights they give women, the more they going to act like they’re domineering over a man.”

A total of 10 men endorsed the savior/cheerleader function for women in relationships, often seeing them as essential for psychological health, motivation, and following a good path in life. For example, several men talked about women as a potential path out of homelessness; “She wants you to be the person that she feels like you’re capable of being, which is not…being homeless on Skid Row.” Another respondent stated that a woman is essential for motivation and direction in life:

…somebody that can help you direct yourself into the right way because a lonely man by himself, he’s liable to do anything…because I’m one of them. But if I had a good woman to stand by my side, just come on, let’s straighten this up and push forward. Maybe I need like a football team, she’ll be my cheerleader…. a good woman can just, you know, they got some kind of way….Keep positive thoughts in his head and direct in the right way and love him like the woman’s supposed to love a man.

Lack of Access to Partners

Eleven men described how being homeless degraded their self-esteem or self-confidence and thereby their interest in as well as ability to pursue partners for relationships. Some of these men felt that their low social status made them virtually unattractive to women, and that their status as homeless men was somehow permanently inscribed on their persona. For example:

…there’s something on my forehead that says homeless or not good enough or income bracket, you know what I mean? …you’re stuck on a low budget type tag on your head. So most women look for an income bracket… Not so much what you’re wearing, but where you’re living. You open your mouth and you say you’re living-because you can’t lie to her, she’s going to find out-you tell her you’re living downtown, okay, alright. You know, it doesn’t fit because she’s living in Beverly Hills….So that isn’t compatibility… Economic status. More so than compatibility, emotionally. They’ll cut you off real quick.

These men described how they felt that those not living on the street believed that homeless people should only date other homeless people. Furthermore, some men described how they felt society placed an additional stigma on homeless men with partners or families on the street, which further discouraged them from trying to have or maintain relationships. With respect to homeless men with families, one respondent said that “society would be shocked. Most people don’t want to even look at a situation like that [homeless man with a family], because it’s very, very depressing.”

Structural/Logistical Barriers to Relationships

A total of twelve men described how living on the street and being forced to rely on the resources provided by homeless shelters as well as the rules laid out by these shelters effectively prevented them from having long-term relationships on the street. Men explained that shelter rules directly blocked any potential for relationships through rules for gender segregation; “It’s like shelters are segregated based on men and women and it’s just really not easy at all if you’re homeless to even be with anybody.” To another participant, this enforced gender segregation was too much to tolerate as a couple:

You’ve got people in here that have a wife on the other side over here and this husband can’t sleep with his wife because he’s homeless and he can’t provide for his wife. But he’s got to sit over here and look at his wife across the room. That makes you feel less than a man.

Men also described how the alternative to sleeping apart in shelters was living on the street or outside “on the grass,” or “in boxes,” which was not a respectable way to live as a couple; “what kind of life is that if you’ve got your woman under a blanket on the grass all night?” Furthermore, they indicated that homeless men simply could not provide the proper shelter or protection for their partners – not to mention resources or even basic hygiene. For example:

You’ve got to be crazy to be in a serious relationship when you’re homeless… she has her sexual - things she needs to keep together on the street. A woman also has her menstruation. It’s just a whole different being - her situation is different than him at that level. It’s just not going to work. He’s got to make sure she’s eating. He’s got to watch out for other men that may be trying to prowl at night…

Instability of Relationships

Seventeen men (over half of the sample) described the ephemeral nature of relationships on the street, highlighting the fact that the harshness of conditions on the street leads to a situation where women pair up with homeless men only temporarily while these men are able provide some money, drugs, protection, or other sustenance – and will leave the man once these resources run dry. The majority of these men described temporary or unstable relationships based on the opportunistic exchange of sex (from the woman) for drugs or other resources (from the man). For example,

…the relationship is centered around using. Usually when the cocaine runs out, the relationship is over - for like a week I guess. They get back together, when the [social services] checks come out…they’re back together. But after they smoke that money out, there’s usually a separation. . .

Men also described temporary relationships between men and women in which the man provided protection in exchange for sex. While some men described how women would skip from one male protector to another depending on who seemed to be most capable of providing protection, or would attempt to ensure that they had multiple protectors by having relationships with several men. For example,

Well, a woman down here -she’s a little bit scared, so she needs someone to protect her….but after she sees that maybe this guy is not going to do anything to help himself, or maybe he’s crazy, she seeks to find somebody else….if that will help her get off the sidewalk, she will have a relationship with them.

Homeless Relationship Patterns

We used a combination of relationship length and reported patterns of sexual fidelity to create a mutually exclusive set of four relationship types that categorized all sexual partners in the sample: (1) long-term monogamous (months or years), (2) long-term non-monogamous (months or years), (3) short-term non-monogamous (days to weeks), and (4) one-time encounter. Five men described monogamous relationships within the last 6 months, and two additional men had only had a single sexual encounter in the last six months (both with non-monogamous casual partners). The remaining 23 men all described two sexual events with two different non-monogamous partners within the last 6 months. Ten of these men had two different short-term non-monogamous partners, and an additional nine men had two different one-time casual encounters. An additional four men described having sex with a long-term non-monogamous partner and also a one-time casual partner in the last 6 months.

Of the five men with monogamous relationships, four of them reported not using condoms for either of the two sexual events. Of the 23 men who had encounters with two different non-monogamous partners over the last 6 months, only four men used condoms for both encounters. The remaining men used a condom for one encounter but not the other, or did not use a condom for either event. Overall, this presents a picture of a minority of homeless men who were in committed, monogamous relationships. The majority of homeless men were involved in short-term, opportunistic, and often overlapping relationships with different types of partners – and using condoms inconsistently if at all.

Idealization of Non-monogamous Partners

Out of the 25 men who described having sex with non-monogamous partners, 15 of these men described these non-monogamous (and often brief) relationships with women in elaborate, often idealistic terms. There were three main patterns in these narratives. The first pattern was to describe casual, one-time encounters in elaborate ways that indicated hope for a future potential relationship, even though there were no plans (and in some cases no possibility) for future encounters. Ten men displayed this pattern in their narratives. For example, “she was very pretty, and I had not run into something of her measure – to be so willing to accept me [in a long time]. She could have been a nice goddess.” This encounter was out of state and very unlikely to result in a second meeting, as was the case with many of these idealized one-time encounters; “‘I’ll never forget her. But she said she’ be downtown…and “I’ll run into you again,” but I haven’t and it’s been like six months.” In some cases, these idealized partners were sex workers. One man described his attempt to reform a sex worker (which failed when she went back to sex work): “I figured I could take her, dip her in some water, polish her up and pretty much show her a better way…” Another man described how he wished he had married a sex worker that he used to frequent; “In a way, I kind of fell in love with the big thing…. Damn, I wish I would have had married her. It’s all history now. From what I heard on the street is she’s dead.”

The second pattern in these narratives was to use idealized descriptions of their non-monogamous sexual partners to justify not using condoms, shown by six men in the sample. For example, “She comes from a good family unit. She’s educated, she has strong values. That’s the only reason I didn’t use protection. I know her, I know her upbringing, I know her family, I know she doesn’t sleep around…”

The third pattern that homeless men displayed in their descriptions of partners and relationships was to idealize their partners in direct comparison to themselves, thereby explaining why they did not deserve to have subsequent encounters or interactions with these women. Five men displayed this pattern in their narratives. For example, one man described himself as a “drifter” and said that although he slept with housed women he always left quietly the next morning, not wanting to burden the women with his presence. Another man had a sexual encounter with a woman whom he greatly admired but said he did not plan to repeat it because, “I’m a bad apple. I’m a bad seed. I’m a bad example.”

Monogamy Narratives

Five men reported monogamous relationships; two were described as “wives,” one as a “fiancé” and two as “steady girlfriends.” Notably, four of these female partners were housed. None of the men lived together with their female partners. All of these men described very infrequent contact with their partners – once per month or less. Despite such infrequent contact, these men described what they perceived as complete fidelity and trust in their relationships, often cast in religious terms. The sexual encounters that men described with these monogamous partners involved either no or very light substance use (only three events involved drinking, and one some light marijuana use). These narratives strongly emphasized resisting temptation – both from drugs and from other women. For example, one man stated:

A second thing that homeless men always encounter is they’re being propositioned by females that have drug habits. I’ve been married 26 years and every other day I get a proposition, but I don’t believe in drugs and I’m not cheating on my wife. I don’t bring no infidelity in my relationship, and that’s why I’ve been married as long as I have.

For the most part, these men in monogamous relationships did not voice the same themes of relationship barriers, lack of partner availability, and other reasons why relationships on the street were not feasible. In fact, one man indicated that he thought relationships on the street were actually stronger than off of the street:

Some homeless couples - from what I can observe - their relationships are stronger than people in more of a normal situation, because they really depend and take care of each other, and - push come to shove - they do what it takes to take care of each other. And I have seen people in normal relationships. They’re too comfortable - they take things for granted….

Quantitative Results

Tables 2 and 3 present descriptive statistics for the variables included in the multi-level logistic regression model. Table 2 presents partner/relationship level variables and Table 3 presents respondent level variables. The 305 respondents discussed 665 relationships with female sex partners: 25% named 4 partners, 12% named 3 partners, 21% named 2 partners and 43% named 1 partner.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Characteristics of Respondents’ Partners and Relationships (n=665)

| Partner/Relationship Level Variables | Mean (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||

| Monogamy | 31.28 | |

| Partner and Relationship Characteristics | ||

| Partner is homeless | 37.14 | |

| Partner has a steady job | 32.03 | |

| Frequency of contact between respondent and partner | 2.4 (1.36) | |

| Respondent feels emotionally close to partner | 46.77 | |

| Respondent received tangible support from partner | 29.17 | |

| Respondent believed partner drank to intoxication last 6 months | 50.23 | |

| Respondent believed partner used drugs last 6 months | 51.73 | |

| Partner’s Social Network Connections | ||

| Centrality (closeness) of partner | .02 (.07) | |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Characteristics of Respondents (n=305)

| Respondent Level Variables | Mean (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 45.79 (10.55) | |

| Respondent ethnicity – Black | 73.11 | |

| Respondent ethnicity – Hispanic | 11.15 | |

| Respondent ethnicity – White | 9.84 | |

| Respondent ethnicity – Other | 5.90 | |

| Income (dollars per month) | 448.31 (427.11) | |

| Months homeless in lifetime | 66.59 (72.59) | |

| Mental Health | ||

| PTSD | 42.95 | |

| MHI-5 (mood disorder screener) | 58.19 (22.11) | |

| Sexual and Relationship Characteristics | ||

| Non-heterosexual | 8.85 | |

| Total female partners in past 6 months | 3.68 (5.75) | |

| Condom efficacy | 3.31 (.65) | |

| Negative condom beliefs | 2.10 (.83) | |

| Culturally Relevant Relationship Beliefs | .02 (.24) | |

| Social Network Norms | ||

| % of non-sex partners in social network rated as likely to engage in risky sex | 20 (27) | |

| % of non-sex partners in social network who are homeless | 21 (26) | |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 4 presents the results of the multi-level multivariate model testing associations with monogamy for a particular partner. The model identified significant correlates of monogamy with a particular partner at both the individual and partner/relationship level. At the individual level, being older (p < .05), self-identifying as Black (p < .10), and positive HIV status (p < .05) were all associated with lower odds of being in a monogamous relationship.

Table 4.

Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) from Multi-level Multivariate Logistic Regression Model Predicting Monogamy with a Particular Partner

| Variable | Monogamy (n=305 respondents, 665 partners)

|

|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | |

| Individual characteristics | |

| Age | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99)* |

| Respondent ethnicity – Black (vs. White) | 0.32 (0.08, 1.22) # |

| Respondent ethnicity – Hispanic (vs. White) | 0.56 (0.10, 3.07) |

| Respondent ethnicity – Other (vs. White) | 0.26 (0.04, 1.65) |

| Income | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| Months homeless lifetime | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) |

| PTSD | 0.56 (0.23, 1.36) |

| MHI | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) |

| HIV status | 0.22 (0.06, 0.77)* |

| Non-heterosexual | 0.36 (0.08, 1.58) |

| Total female partners in past 6 months | 0.86 (0.73, 1.03) |

| Condom efficacy | 1.68 (0.78, 3.61) |

| Negative condom beliefs | 0.75 (0.41, 1.38) |

| Culturally Relevant Relationship Beliefs | 0.53 (0.10, 2.74) |

| Proportion of alters homeless | 1.41 (0.25, 8.17) |

| Proportion of non-sex partners in social network rated as likely to engage in risky sex | 0.33 (0.07, 1.61) |

| Partner/Relationship Level Variables | |

| Partner is homeless | 0.28 (0.10, 0.78)* |

| Partner has a steady job | 1.57 (0.72, 4.71) |

| Frequency of contact between respondent and partner | 1.28 (0.94, 1.75) |

| Respondent felt emotionally close to partner | 3.10 (1.23, 7.83)* |

| Respondent received tangible support from the partner | 1.12 (0.47, 2.66) |

| Respondent believed partner drank to intoxication last 6 months | 0.51 (0.23, 1.10) # |

| Respondent believed partner used drugs last 6 months | 0.41 (0.16, 1.02) # |

| Centrality (betweenness) of partner in respondent’s network | 1.15 (1.08, 1.23)** |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Several partner and respondent level variables were associated with monogamy. Respondents were much less likely to be in a monogamous relationship with a female partner if she was homeless; the odds were reduced by 72% (p < .05). If the respondent believed a sexual partner had used drugs or drunk alcohol to the point of intoxication in the last 6 months, this was associated with 59% and 49% drop in the odds of being in a monogamous relationship with this partner, respectively (p < .10). The odds of being in a monogamous relationship were 3.1 times higher if respondents felt emotionally close to their partners (p < .05). Finally, the more central the partner was to the respondent’s network (in terms of betweenness), the more likely they were to engage in a monogamous relationship. Each one point increase in betweenness centrality corresponded to a 15% increase in the odds of being in a monogamous relationship.

Several variables were not significantly associated with monogamy, including frequency of contact with the partner, partner’s job status, and tangible support given to the partner. In addition gender-related beliefs were not significant in the final model; Component 1 dropped out of the model at the bivariate stage and Component 2 was not significant. Likewise, mental health status was not predictive of monogamy, nor was the proportion of alters in men’s sexual networks who were homeless or perceived to engage in high risk sexual behavior.

Discussion

This study represents the culmination of several qualitative and quantitative analyses over three years of a large study. By examining the data from a wide variety of perspectives, including men’s models of risk from sexual and romantic relationships (Brown, et al., 2012), men’s beliefs regarding masculinity and gender roles (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012), and the integrative relationship-centered perspective taken in the current study, we have been able to build an increasingly nuanced understanding of the multiple social, structural, and cultural constraints and causal pathways leading to risky sexual behavior among homeless men living on Skid Row.

The current study built upon these previous investigations of sex and relationships on the street to conduct a focused examination of the psychological, social, and structural determinants of different types of sexual relationships among homeless men in Skid Row. Overall, our analyses illustrated how men maintained hopes and dreams of idealized, committed relationships despite (for the most part) being unable to realize these dreams while living on the street. They also showed how these idealized hopes and dreams in some cases lead to or were used to justify risk behaviors. In particular, analyses pointed to a mixture of social and structural barriers to men actualizing a normatively desired (but infrequently attained), low risk behavioral pathway –being in committed, monogamous relationships.

Reinforcing the results of a previous quantitative analysis (Kennedy, Brown, et al., 2012), most men described idealized models of male-female relationships wherein the male played the role of provider and protector yet shared decision-making power with his female partner in a “50/50” arrangement. A significant proportion of men also emphasized the role of a woman in motivating a man to help him succeed and successfully surpass his struggles in life. However, when discussing the reality of relationships on the street, men indicated frustration and disappointment on multiple levels. They emphasized their relative lack of attractiveness as mates and the poor quality of available partners on Skid Row. They also described how the stigma associated with being a homeless man often made them lose the hope or motivation to interact with women. Additionally, men described myriad structural barriers to stable relationships, most of them imposed by the rules and regulations of homeless shelters. Several men stated directly that trying to live as a couple within the shelter system was untenable due to rules segregating men and women as well as the shame, frustration, and sheer logistical difficulties of having to live and sleep in separate quarters. To these men, the only alternative is living as a couple on the street, which would bring a host of additional struggles – including increased physical danger, unclean conditions, threats from other homeless men, and the added public stigma of being the supposed provider for an openly visible homeless family.

Men’s narratives of sex and relationships on the street clearly followed from their descriptions of barriers to stable relationships. They described relationships as mostly short, opportunistic, and mutually exploitative. Their descriptions of their own recent sexual events revealed a high proportion of temporary partnerships and a low rate of condom use during these encounters. Surprisingly, men quite often idealized these temporary partnerships, describing hopes and dreams of a future together even if they had no reasonable hope of seeing the partner again, or if the partner was a sex worker. Often, these idealized narratives fed into men’s reasoning for why it was safe to forego condom use. In other cases, men used these idealized descriptions of sexual partners to justify to themselves why they were not worthy of a relationship with those partners.

The minority of men who did describe successful committed relationships while living on the street did not show the patterns described above, in some cases claiming that homeless relationships were stronger and more cohesive than those among housed partners. Consistent with this pattern, quantitative analyses indicated that men who reported feeling emotionally close to their partners were also more likely to report monogamy. Also, consistent with men’s narratives about women on the street being poor quality partners, men were significantly less likely to report a monogamous relationship with homeless (as opposed to housed) female sexual partners. Similarly, a previous study found that homeless men feared that engaging in romantic partnerships on the street would reinforce existing substance use habits or encourage them to relapse into old drug use habits (Brown, et al., 2012), and men described relationships based on substance use as undesirable in the qualitative portion of this study. Consistent with these findings, our quantitative results indicated that men were less likely to report monogamous relationships with substance-using partners.

Some patterns observed in our quantitative model were not necessarily expected and the qualitative analysis did little to shed light on these findings. For example, older men and men who self-identified as Black were less likely to report monogamous relationships. Men who reported positive HIV status were less likely to report monogamy, which could be due either to a pre-existing pattern of high-risk sexual behavior, or the further social marginalization that positive HIV status incurs (Alonzo & Reynolds, 1995; Takahashi, 1997) above and beyond the social stigma attached to homelessness alone (Courtenay, 2000; Ware, Wyatt, & Tugenberg, 2006). Such men are likely viewed as particularly unattractive mates, as has been documented with other HIV positive populations (Adam & Sears, 1994). Similarly, age, which was also associated with lower chances of monogamy, could be an indicator of less attractiveness as a mate and therefore fewer opportunities to develop a committed relationship.

Finally, men whose partners were on direct social pathways between other members of their network were more likely to report monogamy with these sexual partners. This certainly makes intuitive sense, as such partners are more likely to be “social mediators” connecting other elements of men’s social networks with each other. This position yields more access to information, which would make it more difficult for men to hide other, overlapping relationships. Although it did not collect social network data, another study found that couples who reported overlapping social networks also self-reported less sexual infidelity (Treas & Giesen, 2000).

Conclusions and Limitations

Homeless men’s engagement in sexual risk behaviors is a problem with complex interdependencies that defy simple intervention strategies. These risk behaviors are partially rooted in deep social structural divisions within society and the resultant psychological and behavioral patterns than ensue (Bourgois, 1998), but the effect of social structural barriers is mediated through several more proximal mechanisms. Given the rich and complex nature of the problem, it is no small wonder that simple, mono-causal explanations of sexual risk behavior among homeless men (e.g., high risk sexual behavior is primarily a coping strategy for low socioeconomic status; Courtenay, 2000) have poor explanatory power or are simply wrong.

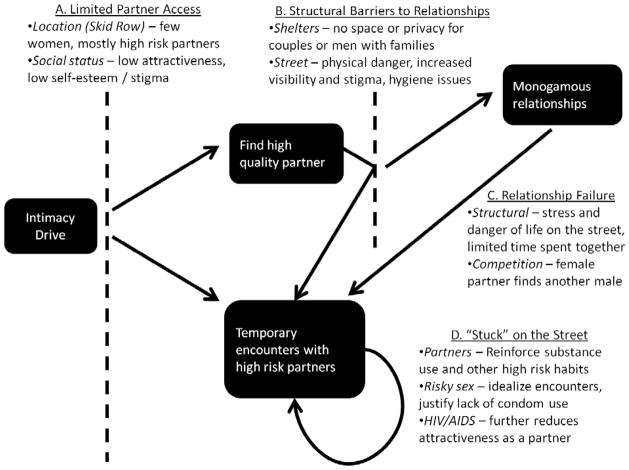

Using qualitative and quantitative analysis to uncover the mechanics surrounding different types of relationships and sexual encounters in this case has helped to lay bare some of the fundamental emotional drivers, social dynamics, and structural features that decrease opportunities for committed relationships on the street. Figure 1 presents a holistic model of the multiple structural, social, and psychological dynamics that lead to homeless men’s high risk sexual behavior, despite their idealization of committed relationships and longing for intimacy with high quality partners. Specifically, this model proposes that despite the drive for intimate, committed relationships, homeless men have limited partner access due to the population composition of Skid Row, as well as their own low social status and the stigma of being homeless (see Figure 1, A), which leads those seeking intimacy towards temporary, high risk encounters with risky female partners. Furthermore, the structural constraints of the shelter system and the dangers of living on the street further conspire to limit men’s relationship possibilities and to thwart emerging monogamous relationships (see Figure 1, B). Even monogamous partnerships that do coalesce are subject to the continuing risks and pressures of life on the street, threatening their long-term viability (see Figure 1, C). Finally, the consequences of temporary, high risk sexual encounters (including STIs such as HIV) further limit men’s relationship opportunities and reinforce their high risk behaviors (see Figure 1, D).

Figure 1.

Holistic Model of High Risk Sex among Homeless Men

Not everything is amenable to intervention. It would not make sense (or be ethical) to try to inhibit homeless men’s desires for intimacy, nor is it possible to interrupt the dynamics of sexual selection that make male resources a large component of female choice (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). However, the structural barriers to relationships inherent to the way services are provided to homeless men present a legitimate and feasible target for intervention. That is, housing interventions that provide some autonomy to men (or women) in whether they are allowed to have members of the opposite sex spend the night would provide a work-around to the multiple logistical barriers to relationships described by homeless men in this study. Given homeless men’s concerns with physical safety in relationships, any structural interventions that improved security could help ameliorate one of the structural factors blocking relationships. Finally, stigma reduction interventions - which have been applied to clinical conditions such as HIV/AIDS (Mahajan, et al., 2008) and mental illness (Dalky, 2011), but could also be applied broadly to social “conditions” like homelessness – could also help reduce one of the psychological barriers men described to establishing and maintaining relationship on the street.

The current study benefited from funding for a multi-year investigation, which allowed for a multi-stage data collection design and provided the necessary time and resources for several analytic “cuts” at both qualitative and quantitative data. Nevertheless, we were not able to collect qualitative and quantitative data on all of the causal processes involved in determining sexual risk on the street. For example, despite having rich and detailed quantitative data on homeless men’s social networks, we did not conduct qualitative interviews regarding the nature of these networks. As such, our inferences regarding the relationship between partner betweenness centrality and monogamy are based more on supposition than on grounded ethnographic findings. However, as multiple previous steps in the analytic process described in the current study, this presents yet another hypothesis generated, awaiting further data collection and analysis.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments This research was supported by NICHD-R01HD059307 (Wenzel). Many thanks to Mary Lou Gilbert, Fred Mills, and Rick Garvey for their critical efforts during field work and interviewing. We would also like to thank the men we interviewed on Skid Row for their trust and patience during the interview process. This research would not have been possible without the cooperation of participating shelters and meal lines in downtown Los Angeles: Los Angeles Mission, Midnight Mission, Union Rescue Mission, New Image Emergency Shelter, St. Vincent Cardinal Manning Center, Fred Jordan Mission, and Emmanuel Baptist Rescue Mission.

References

- Adam BD, Sears A. Negotiating sexual relationships after testing HIV-positive. Medical Anthropology. 1994;16(1–4):63–77. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1994.9966109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo AA, Reynolds NR. Stigma, HIV and AIDS: An exploration and elaboration of a stigma trajectory. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;41(3):303–315. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi L, Keim S, von der Lippe H. Social influences on fertility. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(1):23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. The moral economies of homeless heroin addicts: Confronting ethnography, HIV risk, and everyday violence in San Francisco shooting encampments. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33(11):2323–2351. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen AM, Williams M, McCoy HV, McCoy CB. Crack smokers’ intention to use condoms with loved partners: Intervention development using the theory of reasoned action, condom beliefs, and processes of change. AIDS Care. 2001;13(5):579–594. doi: 10.1080/09540120120063214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Kennedy D, Tucker J, Wenzel S, Golinelli D, Wertheimer S, et al. Sex and relationships on the street: How homeless men judge partner risk on Skid Row. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(3):774–784. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9965-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Schmitt DP. Sexual Strategies Theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review. 1993;100(2):204–232. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KE, Lee BA. Name generators in surveys of personal networks. Social Networks. 1991;13(3):203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS in the United States. CDC HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. 2008 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/us.htm.

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Tashakkori A. Editorial: Differing perspectives on mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(4):303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Dalky HF. Mental illness stigma reduction interventions: Review of intervention trials. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0193945911400638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drigotas SM, Rusbult CE. Should I stay or should I go? A dependence model of breakups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62(1):62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Fullilove RE, Peacock D. Are HIV/AIDS prevention interventions for heterosexually active men in the United States gender-specific? American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(6):981–984. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJL. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. The Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Griffin D. Dyadic data analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf D, Sher KJ, editors. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 3: Data analysis and research publication. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker WP. The construct validity of cultures: Cultural diversity, culture theory, and a method for ethnography. American Anthropologist. 2002;104(1):106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB. Applying the theory of reasoned action to AIDS risk behavior: Condom use among Black women. Nursing Research. 1991;40(4):228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MR, Shefer T, Crawford M, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC. Gender attitudes, sexual power, HIV risk: A model for understanding HIV risk behavior of South African men. AIDS Care-Psychological And Socio-Medical Aspects Of AIDS/HIV. 2008;20(4):434–441. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Brown RA, Golinelli D, Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Wertheimer SR. Masculinity and HIV risk among homeless men in Los Angeles. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027570. No Pagination Specified. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Tucker J, Green H, Golinelli D, Ewing B. Unprotected sex of homeless youth: Results from a multilevel dyadic analysis of individual, social network, and relationship factors. AIDS and Behavior. 2012:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Wenzel S, Tucker J, Green H, Golinelli D, Ryan G, et al. Unprotected sex of homeless women living in Los Angeles County: An investigation of the multiple levels of risk. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):960–973. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BA, Price-Spratlen T. The geography of homelessness in American communities: Concentration or dispersion? City & Community. 2004;3(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22:S67–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, Bernard HR, Killworth PD, Shelley GA, Johnsen EC. Eliciting representative samples of personal networks. Social Networks. 1997;19(4):303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler M, Bogart L, Elliott M, McKay T, Suttorp M, Schuster M. Psychosocial correlates of unprotected sex without disclosure of HIV-positivity among African-American, Latino, and White men who have sex with men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):736–747. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9363-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr DP, Langefeld CD, Katz BP, Caine VA. Behavioral intervention to increase condom use among high-risk female adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1996;128(2):288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlman J. Masculine identity and HIV/AIDS risk behavior among African-American men. Practicing Anthropology. 2008;30(1):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Power R, French R, Connelly J, George S, Hawes D, Hinton T, et al. Health, health promotion, and homelessness. BMJ. 1999;318(7183):590–592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2004;9(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MJ, Clark RA, Charlebois ED, Tulsky J, Long HL, Bangsberg DR, et al. HIV seroprevalence among homeless and marginally housed adults in San Francisco. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1207–1217. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romney AK, Weller SC, Batchelder WH. Culture as consensus: A theory of culture and informant accuracy. American Anthropologist. 1986;88:313–338. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Stern SA, Hilton L, Tucker JS, Kennedy DP, Golinelli D, et al. When, where, why and with whom homeless women engage in risky sexual behaviors: A framework for understanding complex and varied decision-making processes. Sex Roles. 2009;61(7–8):536–553. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 465–485. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM. The socio-spatial stigmatization of homelessness and HIV/AIDS: Toward an explanation of the NIMBY syndrome. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(6):903–914. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treas J, Giesen D. Sexual infidelity among married and cohabiting Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(1):48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Wenzel S, Golinelli D, Kennedy D, Ewing B, Wertheimer S. Understanding heterosexual condom use among homeless men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, & Development. Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-ltem short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):904–910. doi: 10.1080/09540120500330554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman S, Faust K. Social network analysis: Methods and applications. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC. Cultural consensus theory: Applications and frequently asked questions. Field Methods. 2007;19(4):339–368. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel S, Rhoades H, Hsu H-T, Golinelli D, Tucker J, Kennedy D, et al. Behavioral health and social normative influence: Correlates of concurrent sexual partnering among heterosexually-active homeless men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0066-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]