Abstract

One of the early events of the DNA damage response (DDR), particularly if the damage involves induction of DNA double-strand breaks, is remodeling of chromatin structure characterized by its relaxation (decondensation). The relaxation increases accessibility of the damaged DNA sites to the repair machinery. We present here a simple cytometric approach to detect chromatin relaxation based on the analysis of the proclivity of DNA in situ to undergo denaturation after treatment with acid. DNA denaturation is probed by the metachromatic fluorochrome acridine orange (AO) which differentially stains single-stranded (denatured) DNA by fluorescing red and the double-stranded DNA by emitting green fluorescence. DNA damage was induced in both human leukemic TK6 cells and mitogen-stimulated human peripheral blood lymphocytes by exposure to UV light or by treatment with H2O2. Chromatin relaxation was revealed by diminished susceptibility of DNA to denaturation, likely reflecting decreased DNA torsional stress, seen as soon as 10 min after subjecting cells to UV or H2O2. While cells in all phases of the cell cycle showed a comparable extent of chromatin relaxation upon UV or H2O2 exposure, H2AX was phosphorylated on Ser139 predominantly in S-phase cells. The data are consistent with the notion that chromatin relaxation is global, affects all cells with damaged DNA, and is a prerequisite to the subsequent steps of DDR that can be selective to cells in a particular phase of the cell cycle. The method offers a rapid and simple means of detecting genotoxic insult on cells.

Keywords: UV light, oxidative DNA damage, H2AX phosphorylation, cell cycle, DNA denaturation, acridine orange, metachromasia, ssDNA, lymphocytes

Introduction

The DNA damage response (DDR) is a complex, highly choreographed process involving the induction of a plethora of molecular interactions between numerous molecules. Halting cell cycle progression and division to prevent transfer of DNA damage to progeny cells, engagement of the DNA damage repair machinery, and/or activation of the apoptotic pathway to exterminate cells whose damaged DNA cannot be successfully repaired are the three critical goals of the DDR (reviewed in refs. 1-7).

One of the early events of the DDR, preceding ATM activation, is remodeling of chromatin that involves its relaxation (decondensation).8-15 In fact, ATM activation appears to be triggered by chromatin changes induced by the altered torsional stress of the DNA double helix that occurs following DNA damage.16 High mobility group proteins (HMGs) play an important role in organization of chromatin that provides a dynamic response to DNA damage.15,17,18 HMGs and histone H1 form a network of proteins that is continuously moving along the chromatin fiber and interacting with each other and with internucleosomal DNA. HMGs are among the most extensively modified nuclear proteins, phosphorylated, acetylated, methylated, ribosylated or sumoylated in response to changes in the physiological state of the cell, induction of cellular stress or cell cycle phase.19 This network provides a continuous highly dynamic interplay between a variety of nuclear structural proteins, modulating their binding to each other and to nucleosomes.17-21 Of particular importance is the nucleosome binding protein HMGN1, which modulates the architecture of chromatin and affects the levels of post-transcriptional modifications of the tails of nucleosomal histones. HMGN1 binds to nucleosomes and reduces the rate of histone H3 phosphorylation on Ser10,22 a modification that facilitates chromatin condensation like that occurring during mitosis.23 Thus, DNA damage induced activation of HMGN1 via post-translational modification may be directly associated with chromatin decondensation and, as a result, activation of ATM.

TIP60 histone acetyltransferase has also been shown to play a role in modulation of chromatin dynamics. In response to DNA damage, in addition to acetylation of histone H2AX, which is a prerequisite for its phosphorylation on Ser139, TIP60 regulates the ubiquitination of H2AX via the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBC13.24 Sequential acetylation and ubiquitination of H2AX by TIP60-UBC13 promotes enhanced histone dynamics, which in turn stimulates a DNA damage response. It should be noted that the presence of wt p53 appears to be critical for the induction of chromatin relaxation upon DNA damage10,25 perhaps through its effect on the tumor suppressor p33ING2.26 Chromatin relaxation enhances the accessibility of sites of DNA damage to the repair machinery.

The methods used to measure chromatin relaxation such as assessment of DNA accessibility to nucleases25 or net phosphorus to nitrogen ratio obtained from the elemental maps with an imaging filter electromagnetic spectrometer27 or energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy28 are complex and cumbersome. To date, chromatin relaxation during DDR has yet to be assessed by flow or image-assisted cytometry.

One of the markers of chromatin condensation/relaxation is the propensity of DNA in situ to undergo denaturation after treatment with heat or acid. The extent of DNA denaturation in chromatin can be probed by the metachromatic fluorochrome acridine orange (AO), which upon binding to double-stranded (ds) DNA (by intercalation) fluoresces green with maximum emission at 530 nm while its interaction with the denatured, single-stranded DNA results in red fluorescence emission at ~640 nm.29,30 Therefore, the ratio of red to green fluorescence of AO-stained cells provides information on the relative proportion of denatured to ds DNA, respectively. It has been observed that DNA in condensed chromatin of mitotic31,32 or apoptotic cells32-34 as well as in quiescent G0 cells35 was distinctly more denatured when stressed with heat or acid than DNA of interphase cells having less condensed chromatin. This feature provided a convenient marker to distinguish mitotic, apoptotic or G0 cells by flow cytometry. We hypothesized that relaxation of chromatin during DDR may also be detected by an increase in resistance of DNA in situ to denaturation. The present data indicate that, indeed, exposure of cells to the DNA damaging agents UV light or the oxidant H2O2 rapidly enhances the resistance of DNA in situ to denaturation.

Results

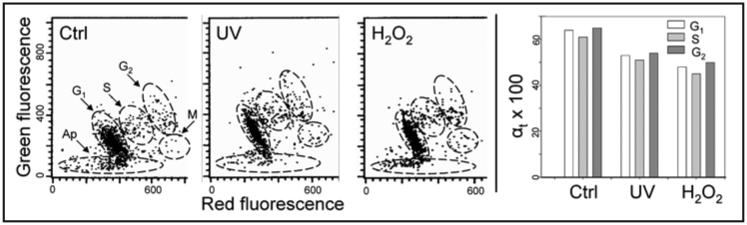

Figure 1 presents the analysis of changes in chromatin structure of TK6 cells treated with UV or H2O2 as detected by the induction of partial DNA denaturation by acid.20 It is quite evident that treatment with UV or H2O2 led to an increase in intensity of green and a decrease of red fluorescence, indicating that DNA in the treated cells was more resistant to acid (0.1 N HCl) driven denaturation. The degree of DNA denaturation is presented as the value αt, which is the ratio of the mean value of red fluorescence intensity of the cell population (reporting AO-interactions with the denatured, ssDNA) to the mean total (red plus green) intensity of fluorescence (reporting AO interactions with ssDNA and dsDNA, i.e., total DNA content) of the same cells. Thus, the αt index is an approximate estimate of the fraction of denatured DNA, and theoretically can vary from 0 (all DNA is in ds conformation) to 1.0 (all DNA is ss).30 This ratio decreased in the cells treated with H2O2 or UV compared to untreated control cells with the extent of decrease more pronounced after treatment with H2O2. The UV- or H2O2-induced decrease in αt occurred rather uniformly in all phases of the cell cycle, including mitotic cells (Fig. 1, bar graphs). It should be noted that in addition to the data shown in Figure 1, more detailed studies were carried out testing UV at 50 J/m2 followed by different times of incubation (5–30 min) after exposure to UV, as well as analyzing cells after different times of treatment with H2O2 (5–60 min). The distinct decrease in αt of DNA in TK6 cells was seen as early as 10 min after either their irradiation with 50 J/m2 or incubation with 100 μM H2O2 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Relaxation of chromatin of TK6 cells treated with UV or H2O2 detected by partial denaturation of DNA and staining with AO. Ctrl, untreated cells; UV, the cells were exposed to 100 J/m2 UV light and then cultured for 30 min; H2O2, the cells were cultured with 100 μM H2O2 for 30 min. Cells were fixed then treated with 0.1 N HCl, stained with AO at pH 2.6 and their fluorescence measured by flow cytometry.30 The red and green fluorescence reports AO binding to ssDNA and dsDNA, respectively.29-31 The bivariate distributions (scatterplots) show the intensity of red and green fluorescence of individual cells. Mitotic cells (M) are characterized by a high degree of DNA denaturation, much higher than the interphase cells, which is reflected by their high intensity of red and low intensity of green fluorescence. The G1, S, G2 and M cell clusters were gated as shown by the dashed lines, and the mean intensity of red fluorescence (ssDNA) to total (red plus green) intensity of fluorescence (reporting ssDNA + dsDNA) was calculated for cells in each cell cycle phase, as described.30 This ratio (αt) provides an approximate estimate of the fraction of the denatured (ssDNA) with respect to total DNA content per cell. The mean values of αt (×100) calculated for populations of G1, S, G2 and M cells are plotted as bar graphs (right).

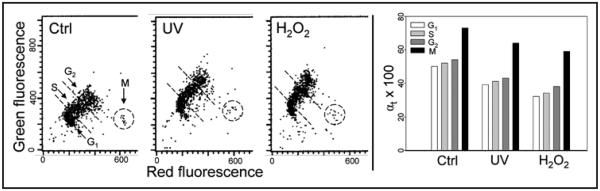

Chromatin changes of proliferating human lymphocytes following treatment with UV or H2O2, as shown in Figure 2. The exposure of lymphocytes to UV or H2O2, as was the case with TK6 cells, led to an increase in resistance of their DNA in situ to denaturation reflected by an increase in intensity of green- and a decrease in red fluorescence after treatment with acid and staining with AO. The effect, expressed as a decrease in αt, was of similar degree in G1, S and G2 cells and was not much different following treatment with UV or H2O2.

Figure 2.

Relaxation of chromatin in mitogenically stimulated lymphocytes after their treatment with UV light or H2O2. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes induced to proliferation by PHA were untreated (Ctrl), exposed to 50 J/m2 UV then cultured for 30 min (UV), or treated in culture with 100 μM H2O2 for 20 min (H2O2). The cells were then fixed, treated with HCl and stained with AO. The extent of their DNA denaturation was assessed by analysis of the intensity of red and green fluorescence by flow cytometry.30 G1, S, G2, M and apoptotic (Ap) cells were identified by their characteristic differences in red and green fluorescence, as described before.32,33,35 Populations of cells in G1, S and G2 were gated as shown by the dashed outlines to obtain mean values of intensity of their red and green fluorescence to estimate the DNA denaturation αt index30 which is shown in the bar-graph to the right.

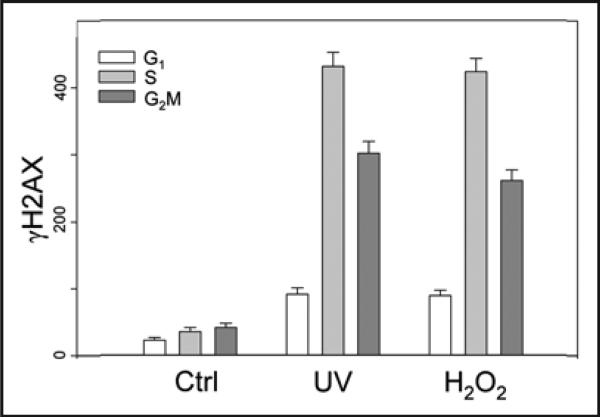

The induction of γH2AX in TK6 cells treated with UV or H2O2 with respect to the cell cycle phase is shown in Figure 3. It is evident that phosphorylation of H2AX induced by UV or H2O2 was cell cycle phase specific, maximal in S phase and minimal in G1 phase cells. The raw data that show the type of bivariate distributions of γH2AX vs. DNA content of cells treated with UV or H2O2 have bas presented previously.36,38

Figure 3.

Induction of γH2AX in TK6 cells treated with UV or H2O2. The cells were untreated (Ctrl), treated with 57 J/m2 UV and then cultured for 30 min (UV), or treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 60 min (H2O2), then fixed. The expression of γH2AX was detected immunocytochemically and measured by cytometry in conjunction with cellular DNA content as described.36,37 By gating analysis the mean values (+SD) of γH2AX expression were estimated for populations of G1, S and G2M cells and plotted as a bar graph.

Discussion

We report here that a very early event of the DDR, relaxation (decondensation) of chromatin can be detected by a method utilizing the metachromatic fluorochrome AO to differentially stain double-stranded versus denatured (ss) DNA. As mentioned, this methodology developed by us several decades ago29,30 has been widely used in variety of applications to distinguish cells differing in their degree of chromatin condensation, such as mitotic31 or quiescent G0,35 cells from the proliferating interphase cells, apoptotic from non-apoptotic cells22,23 or normal from abnormal spermatozoa.34,39 Because optimal staining with AO requires stringent conditions of equilibrium between the dye and DNA (permeabilized cells) the method is more amenable to flow cytometry rather than to microscope imagining. However, with proper control of AO concentration, the method can be applied in microscopy.32

Chromatin decondensation as measured by the decreased predisposition of DNA in situ to denaturation (DNA denaturation index αt) could be detected 10 min after exposure of TK6 cells to UV light (50 or 100 J/m2) or 10 min after treatment with 100 μM H2O2 (Fig. 1). The extent of αt change was approximately similar in the TK6 cells treated with 50 J/m2 as compared with 100 J/m2 of UV light, and lasted for up to 60 min (not shown). Comparable effects were also seen in the case of proliferating normal human lymphocytes (Fig. 2).

The present data demonstrate that chromatin relaxation was global, affecting cells in all phases of the cell cycle, including mitotic cells, i.e., the cells with initially maximally condensed chromatin. In contrast, confirming our earlier findings,36,38 we observed that the induction of γH2AX either by UV or H2O2 was uneven, cell cycle phase dependent and much more pronounced in DNA replicating than in G1 phase cells (Fig. 3). Other steps of DDR induced by H2O2 such as activation of ATM through its phosphorylation on Ser1981, Chk2 activation through Thr68 phosphorylation and p53 activation through Ser15 phosphorylation were also seen to be cell cycle phase dependent and maximal in S-phase cells.37,38 However, the recruitment of Mre11 upon the treatment with H2O2, similar to chromatin relaxation, was shown to be global, affecting all cells regardless of their cell cycle phase.38 Thus, DNA damage triggers chromatin relaxation and Mre11 recruitment with no regard to the cell cycle phase whereas the DDR steps subsequent to chromatin relaxation and Mre11 recruitment appear to be cell cycle-phase dependent, apparently regulated by cell cycle specific factors.

It is not entirely clear why DNA in condensed chromatin shows a higher propensity to denature when stressed by heat or acid compared to DNA in relaxed chromatin. It has been proposed that due to chromatin supercoiling, which is more intense in condensed chromatin, the torsional stress on the double helical structure of DNA is greater which makes the structure less stable and prone to denature (DNA melting) upon exposure to heat or acid.29,31,40 In fact, DNA in the condensed chromatin of metaphase chromosomes, likely due to the increased torsional stress, shows the presence of ss sections sensitive to the ss-specific S1 or mung bean nucleases.41,42 This global torsional DNA stress in nuclear chromatin dependent on the degree of chromatin condensation should not be confused with the local torsional stress that propagates through the chromatin fiber and appears to be essential in transcription regulation.43-45

It should be noted that AO has been used to measure DNA damage and repair in cytometric assays based on the alkaline unwinding of DNA.46-48 Following DNA damage or during nucleotide excision repair (NER) the damaged DNA sections become denatured under alkali conditions and AO is then used to measure the extent of DNA denaturation. Unlike in the present studies, in which we observed a decrease in the extent of DNA denaturation induced by acid following DNA damage, in the alkaline unwinding cytometric assay the increase in extent of DNA denaturation is a marker of DNA damage.

Chromatin dynamics during DDR is currently the focus of wide interest in many disciplines of biology and medicine.6-11,49-52 Remodelling of chromatin is considered to be the prerequisite for further events associated with DNA repair. The cytometric method to detect chromatin relaxation we present here, by virtue of its simplicity, offers an attractive alternative to more complex assays such as those involving assessment of DNA accessibility to nucleases,25 electron spectroscopic analysis of the elemental maps requiring an imaging filter electromagnetic spectrometer27 or energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy.28

Materials and Methods

Cells, cells treatment

Human B cell lymphoblastoid TK6 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Howard Liber of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.53 The cells were grown in 25 ml FALCON flasks (Becton Dickinson Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (all from GIBCO/BRL) at 37.5°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. At the onset of the experiments, there were fewer than 5 × 105 cells per ml in culture such that the cells were in an exponential and asynchronous phase of growth. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes, obtained from healthy volunteers by venipuncture were isolated by density gradient centrifugation as described.54 The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (all from GIBCO/BRL Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) at a density of ~5 × 105 cells/ml. The cells were then treated with 10 μg/ml of phytohemagglutinin (PHA-P, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and incubated in 25-ml (12.5 cm2) polystyrene flasks (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) in a mixture of 95% air and 5% carbon dioxide at 37.5°C for 72 h. The cultures of TK6 cells as well as of nonstimulated and PHA-stimulated lymphocytes were exposed to UV-B light (~300 nm) by placing them onto a UV-light gel illuminator (Fotodyne; West Berlin, WI), as described before36 with the doses as shown in the Figure legends. The cultures were then transferred into the incubator at 37.5°C for up to 60 min. Other cultures were treated with 100 μM H2O2 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for different time intervals, as described in the legends to figures.

Cell staining, fluorescence measurements

The cells were fixed in suspension in 70% ethanol for over 12 h then suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in the presence of 100 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma) at 37°C for 20 min. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 0.1 M HCl followed by a solution phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 2.6) containing of 6 μg/ml of AO, at room temperature. The details of this methodology are presented elsewhere.30 Green (Fl 1) and red (Fl 3) fluorescence were measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) with the standard emission filters. Gating analysis was carried out to obtain the mean values of integrated green and red fluorescence of G1, S and G2M cells as shown in the Figures. The extent of DNA denaturation for cells in each phase of the cell cycle is presented as αt value which represents the ratio of the mean red fluorescence intensity of cells at that phase of the cell cycle divided by the total (red plus green) mean fluorescence intensity of the same cells, as defined previously.29,30 Other details are presented in Figure legends. Cells from the cultures parallel to these analyzed with respect to DNA denaturation as presented above were also subjected to the analysis of histone H2AX phosphorylation (Fig. 3) by the method described by us before.38,55,56

Acknowledgements

Supported by NCI Grant R01 CA 28 704.

References

- 1.Kastan MB, Lim DS. The many substrates and functions of ATM. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:179–86. doi: 10.1038/35043058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helt CE, Cliby WA, Keng PC, Bambara RA, O’Reilly MA. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad3-related protein exhibit selective target specificities in response to different forms of DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1186–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. Initiating cellular stress responses. Cell. 2004;118:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42462–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J-H, Paull TT. ATM activation by DNA double-strand breaks through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Science. 2005;308:551–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1108297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paull TT, Lee JH. The Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex and its role as a DNA-double strand break sensor for ATM. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:737–40. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.6.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziv Y, Bielopolski D, Galanty Y, Lukas C, Taya Y, Schultz DC, et al. Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double-strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:870–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandita TK, Richardson C. Chromatin remodeling finds its place in the DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009:1–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murga M, Jaco I, Soria R, Martinez-Pastor B, Cuadrado M, Yang S-M, et al. Global chromatin compaction limits the strength of the DNA damage response. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1101–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouleau M, Aubin RA, Poirier GG. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated chromatin domains: access granted. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:815–25. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi K, Kaneko I. Changes in nuclease sensitivity of mammalian cells after irradiation with 60Co., gamma-rays. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1985;48:389–95. doi: 10.1080/09553008514551391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruhlak MJ, Celeste A, Nussenzweig A. Spatio-temporal dynamics of chromatin containing DNA breaks. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1910–2. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayoub N, Jeyasekharan AD, Bernal JA, Venkitaraman AR. Paving the way for H2AX phosphorylation: Chromatin changes in the DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1494–500. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.10.8501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gertlitz G, Bustin M. Nucleosome binding proteins potentiate ATM activation and DNA damage response by modifying chromatin. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1641. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa R, Kastan MB. The ATM-dependent DNA damage signaling pathway. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:99–109. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YC, Gerlitz G, Furusawa T, Catez F, Nussenzweig A, Oh KS, et al. Activation of ATM depends on chromatin interactions occurring before induction of DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:92–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerlitz G, Hock R, Ueda T, Bustin M. The dynamics of HMG protein-chromatin interactions in living cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:127–37. doi: 10.1139/O08-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Q, Wang Y. High mobility group proteins and their post-transcriptional modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1794:1159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misteli T, Soutoglou E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:243–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soutoglou E. DNA lesions and DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3653–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.23.7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim J, Catez F, Birger Y, West K, Prymakowska-Bosak M, Postnikov M, et al. Chromosomal protein HMGN1 modulates histone H3 phosphorylation. Mol Cel. 2004;15:573–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juan G, Traganos F, James WM, Ray JM, Roberge M, Sauve DM, et al. Histone H3 phosphorylation and expression of cyclins A and B1 measured in individual cells during their progression through G2 and mitosis. Cytometry. 1998;32:71–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19980601)32:2<71::aid-cyto1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikura T, Tashiro S, Kakino A, Shima H, Jacob N, Amunugama R, et al. DNA damage-dependent acetylation and ubiquitination of H2AX enhances chromatin dynamics. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7028–40. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00579-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubbi CP, Milner J. p53 is a chromatin accessibility factor for nucleotide excision repair of DNA damage. EMBO J. 2003;22:975–86. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Chin MY, Li G. The novel tumor suppressor p33ING2 enhances nucleotide excision repair via inducement of histone H4 acetylation and chromatin relaxation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1906–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bazett-Jones DP, Hendzel MJ. Electron spectroscopic imaging of chromatin. Methods. 1999;17:188–200. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kruhlak MJ, Celeste A, Dellaire G, Fernandez-Capetillo, Muller WG, McNally JG, et al. Changes in chromatin structure and mobility in living cells at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:823–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darzynkiewicz Z, Traganos F, Sharpless T, Melamed MR. Thermal denaturation of DNA in situ as studied by acridine orange staining and automated cytofluorometry. Exp Cell Res. 1975;90:411–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darzynkiewicz Z. Acid-induced denaturation of DNA in situ as a probe of chromatin structure. Meth Cell Biol. 1990;33:337–52. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60537-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darzynkiewicz Z, Traganos F, Carter SP, Higgins PJ. In situ factors affecting stability of the DNA helix in interphase nuclei and metaphase chromosome. Exp Cell Res. 1987;172:168–79. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobrucki J, Darzynkiewicz Z. Chromatin condensation and sensitivity of DNA in situ to denaturation during cell cycle and apoptosis. A confocal microscopy study. Micron. 2001;32:645–52. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(00)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darzynkiewicz Z, Bruno S, Del Bino G, Gorczyca W, Hotz MA, Lassota P, et al. Features of apoptotic cells measured by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1992;13:795–808. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorczyca W, Traganos F, Jesionowska H, Darzynkiewicz Z. Presence of DNA strand breaks and increased sensitivity of DNA in situ to denaturation in abnormal human sperm cells. Analogy to apoptosis of somatic cells. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207:202–5. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darzynkiewicz Z, Traganos F, Andreeff M, Sharpless TK, Melamed MR. Different sensitivity of chromatin to acid denaturation in quiescent and cycling cells as revealed by flow cytometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1979;27:478–85. doi: 10.1177/27.1.86572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halicka HD, Huang X, Traganos F, King MA, Dai W, Darzynkiewicz Z. Histone H2AX phosphorylation after cell irradiation with UV-B: Relationship to cell cycle phase and induction of apoptosis. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:339–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao H, Traganos F, Darzynkiewicz Z. Phosphorylation of p53 on Ser15 during cell cycle caused by Topo I and Topo II inhibitors in relation to ATM and Chk2 activation. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3048–55. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao H, Traganos F, Albino AP, Darzynkiewicz Z. Oxidative stress induces cell cycle-dependent Mre11 recruitment, ATM and Chk2 activation and histone H2AX phosphorylation. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1490–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.10.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evenson DP, Darzynkiewicz Z, Melamed MR. Relation of mammalian sperm chromatin heterogeneity to fertility. Science. 1980;210:1131–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7444440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benham CJ. Torsional stress and local denaturation in supercoiled DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979:3870–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juan G, Pan W, Darzynkiewicz Z. DNA segments sensitive to single strand specific nucleases are present in chromatin of mitotic cells. Exp Cell Res. 1996;227:197–202. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bianchi U, Ferruci L, Pignone D, Vanni R, Mezzanotte R. S1 nuclease removes DNA from metaphase chromosomes: cytological evidence. Basic Appl Histochem. 1985;29:191–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavelle C. DNA torsional stress propagates through chromatin fiber and participates in transcriptional regulation. Nat Struct Molec Biol. 2008;15:123–5. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0208-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kouzine F, Liu J, Sanford S, Chung HJ, Levens D. The dynamic response of upstream DNA to transition-generated torsional stress. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1092–100. doi: 10.1038/nsmb848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freeman LA, Garrard WT. DNA supercoiling in chromatin structure and gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1992;2:156–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rydberg B. The rate of strand separation in alkali of DNA of isolated mammalian cells. Radiat Res. 1975;61:274–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potter AJ, Gollahon KA, Palanca BJA, Harbert MJ, Choi YM, Moskovitz AH, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle phase specificity of DNA damage induced by radiation, hydrogen peroxide and doxorubicin. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:398–401. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thyagarajan B, Anderson KE, Lessard CJ, Veltri G, Jacobs DR, Folsom AR, et al. Alkaline unwinding flow cytometry assay to measure nucleotide excision repair. Mutagenesis. 2007;22:147–53. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fazzio TG, Huff JT, Panning B. Chromatin regulation Tip(60)s balance in embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3302–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huertas D, Sendra R, Munoz P. Chromatin dynamics coupled to DNA repair. Epigenetics. 2009;4:31–42. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.1.7733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altaf A, Auger A, Covie M, Cote J. Connection between histone H2A variants and chromatin remodeling complexes. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:35–50. doi: 10.1139/O08-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou W, Wang X, Rosenfeld MG. Histone H2A ubiquitination in transcriptional regulation and DNA damage repair. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:12–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartz JL, Jordan E, Evans HH, Lenarczyk M, Liber H. The TP53 dependence of radiation-induced chromosome instability in human lymphoblastoid lines. Radiat Res. 2003;159:730–9. doi: 10.1667/rr3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka T, Halicka HD, Traganos F, Darzynkiewicz Z. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX on Ser 139 and activation of ATM during oxidative burst in phorbol ester-treated human leukocytes. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2671–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.22.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka T, Halicka HD, Huang X, Traganos F, Darzynkiewicz Z. Constitutive histone H2AX phosphorylation and ATM activation, the reporters of DNA damage by endogenous oxidants. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1940–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tanaka T, Kurose A, Halicka HD, Huang X, Traganos F, Darzynkiewicz Z. Nitrogen oxide-releasing aspirin induces histone H2AX phosphorylation, ATM activation, and apoptosis preferentially in S-phase cells; involvement of reactive oxygen species. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1669–74. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]