Abstract

A convenient method for the direct construction of quaternary carbons from tertiary alcohols by visible-light photoredox coupling of tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalate intermediates with electron- deficient alkenes is reported.

Forming sterically demanding quaternary carbons by the reaction of nucleophilic carbon radicals with electron-deficient alkenes is attractive for several reasons: the forming bond is unusually long in calculated transition structures (2.2–2.5 Å);1 the rates of addition of tertiary radicals to electron-deficient alkenes are faster than those of Me, primary and secondary radicals;2 and stereoselectivity in the addition of tertiary radicals to prochiral alkenes is typically larger than that of primary or secondary radicals.2a,3,4, Although these appealing features have been recognized for many years,2a,5 this method is not mentioned in a recent comprehensive survey of methods to construct quaternary carbons.6 The considerable potential such bond constructions hold was suggested in our recent formal total synthesis of (−)- aplyviolene, wherein the stereoselective coupling of a tertiary carbon radical, generated by visible-light photoredox decarboxylative fragmentation of N- (acyloxy)phthalimide 1, to α-chlorocyclopentenone 2 was the central step (eq 1).7a This result represented the first utilization of such substrates in a C–C bondforming reaction since their initial disclosure by Okada.8 We surmise that the reason tertiary carbon radicals have not heretofore played a significant role in assembling quaternary carbons is the lack of convenient methods for generating these intermediates from widely available tertiary alcohols.4 Further-more, despite the pronounced advancement of visible- light photoredox-catalyzed transformations in recent years, methods that generate tertiary carbon radicals remain largely unexplored.7b,9 In this communication, we report such a method.

|

(1) |

The method we developed was inspired by Barton’s pioneering introduction of tert-alkyl N-hydroxypyridine- 2-thionyl oxalates for generating carbon radicals from alcohols.10 Although Barton oxalate intermediates can be formed from tertiary alcohols, the instability of these intermediates, which prevents their isolation, and their light sensitivity are likely responsible for their limited use in the formation of quaternary carbons.11–15 Anticipating that related tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates would be more convenient precursors of tertiary carbon radicals, we initially explored conditions to access these compounds.

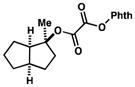

After examining several potential methods for preparing these mixed oxalate diesters, we found that tertiary alcohols smoothly underwent acylation with chloro N-phthalimidoyl oxalate (4, generated in situ from oxalyl chloride and N-hydroxyphthalimide) at room temperature in the presence of Et3N and catalytic DMAP to afford tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates in high yields (5→6, Figure 1). In contrast to N- (acyloxy)phthalimides, which are generally quite stable to aqueous workup and silica gel chromatography, oxalates 6 proved to be much more sensitive. However, we found that the byproducts of their synthesis typically could be removed by simple filtration to furnish the desired product in acceptable purity. tert-Alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates 6a–6k are stable to ambient light and can be easily prepared on multigram scale. Confirmation that this sequence did provide the previously unknown alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates was secured by single-crystal X-ray analysis of oxalate diester 6j.

Figure 1. Synthesis of tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates.

aIsolated yield, bPhth = N-phthalimido

With a general route to tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates in hand, we examined the coupling of oxalate 6a with methyl vinyl ketone. Employing conditions similar to those used in our earlier studies with N-(acyloxy)phthalimides7 resulted largely in decomposition of the oxalate, furnishing coupled product 7a in only small amounts (Table 1, entry 1). Omission of i-Pr2NEt provided an improvement in yield (entry 2), reflecting the instability of 6a to the presence of this amine. The use of i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 resulted in improved yields of 7a (entries 3–9). Whereas using an excess or equal amount of methyl vinyl ketone relative to 6a proved detrimental (entries 1–5),16 optimal yields were obtained when oxalate 6a was present in slight excess (entries 6–10). It was also found that a 1:1 THF-CH2Cl2 solvent mixture was superior to either CH2Cl2 or THF alone (entries 8 and 9). The i- Pr2NEt•HBF4 additive was found to be beneficial even under optimized conditions, as its omission led to lower product yields (entry 10). Finally, [Ru(bpy)3](BF4)2 or the commercially available [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 performed comparably in the reaction (entries 8 and 9). Under the optimized reaction conditions, the coupling of oxalate 6a with methyl vinyl ketone gave ketone product 7a in 82% yield.

Table 1.

Optimization for the coupling of 6a with methyl vinyl ketone.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | oxalate equiv | MVK equiv | Hantzsch ester equiv | additive equiv | solventa | X | Yield (%)b,c |

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | i-Pr2NEt (2.2) | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 16b |

| 2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | none | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 36b |

| 3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (2.2) | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 40b |

| 4 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (2.2) | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 22b |

| 5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (2.2) | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 56b |

| 6 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (2.2) | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 77b |

| 7 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (1.0) | CH2Cl2 | BF4 | 82b |

| 8 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (1.0) | THF/CH2Cl2a | BF4 | 92b |

| 9 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | i-Pr2NEt•HBF4 (1.0) | THF/CH2Cl2a | PF6 | 92b 82c |

| 10 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | none | THF/CH2Cl2a | PF6 | 65c |

1:1 mixture of THF-CH2Cl2; Hantzsch ester = diethyl 1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-3,5-pyridinedicarboxylate.

Yield determined by 1H NMR,

Isolated yield after silica gel chromatography.

The results of our initial survey of the scope of the coupling of tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates with methyl vinyl ketone are summarized in Table 2. In most cases, yields of the coupled products were excellent, ranging from 68–85% (entries 1–7). Chiral oxalates 6c, 6d and 6e coupled with high diastereoselectivity (>20:1) from the sterically most accessible face (entries 3, 4 and 5). The coupling of the estrone- derived precursor 6e is significant as it demonstrates the construction of vicinal-quaternary carbon centers (entry 5). Two nitrogen-containing heterocyclic substrates were also investigated (entries 7 and 8). Piperidinone-derived 6h furnished coupled product 7h in 82% yield, whereas the coupling of indole-containing oxalate 6i proceeded in diminished yield. As expected from our exploratory studies, carrying out the coupling of 6d and 6e with equal equivalents of the oxalate precursor and me- thyl vinyl ketone gave the coupled products in somewhat diminished yields (4 and 5). The reaction of adamantyl oxalate 6j led to the expected product 7j in low yield, with the major product deriving from coupling of the intermediate alkoxycarbonyl radical with methyl vinyl ketone (entry 9). To no surprise, homoallylic oxalate 6k coupled with methyl vinyl ketone to give butyrolactone 7k (entry 7).15a,17

Table 2.

Coupling of tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates with methyl vinyl ketone.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Oxalate | Product | Yield (%)b,c |

| 1 |

6a |

7a |

82b |

| 2 |

6b |

7b |

85b |

| 3 |

6c |

7c |

82b |

| 4 |

6d |

7d |

85b 63c |

| 5 |

6e |

7e |

68b 43c |

| 6 |

6f R = TBS 6g R = PMB |

7f |

81b |

7g |

78b | ||

| 7 |

6h |

7h |

82b |

| 8 |

6i |

7i |

36b |

| 9 |

6j |

7j |

22b |

8j |

65b | ||

| 10 |

6k |

7k |

43b |

1:1 mixture of THF:CH2Cl2,

Isolated yield after silica gel chromatography (average of two experiments),

Isolated yield after silica gel chromatography with 1:1 ratio of oxalate precursor to acceptor,

Phth = N-phthalimido

The scope of this new coupling reaction with respect to the conjugate acceptor is summarized in Table 3. Acceptors possessing a terminal double bond generally performed best in the reaction, with acrylonitrile, phenyl vinyl sulfone, and methyl acrylate providing the coupled products in excellent yield (entries 1–3); the yield was somewhat lower with dimethyl acrylamide (entry 4). Dimethyl fumarate also served as an excellent coupling partner producing 9e in 85% yield (entry 5).

Table 3.

Coupling of 6a with various acceptors.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Acceptor | Product | Yield (%)b |

| 1 |

|

9a |

92b |

| 2 |

|

9b |

89b |

| 3 |

|

9c |

84b |

| 4 |

|

9d |

64b |

| 5 |

|

9e |

85b |

| 6 |

|

9f |

54b |

| 7 |

|

9g |

52b |

| 8 |

|

9h |

72b |

| 9 |

|

9i |

62b |

1:1 mixture of THF:CH2Cl2,

Isolated yield after silica gel chromatography (average of two experiments)

Cyclic acceptors could be utilized also, although the yields of coupled products were slightly lower (entries 6–9). Use of a butenolide acceptor (entry 8) furnished the desired product in 72% yield, with addition occurring exclusively from the face opposite the methoxy substiuent.18 Finally, the activated trisubstituted acceptor 2-carbomethoxycyclopen-2- ene-1-one coupled with tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalate 6a to afford trans product 9i in 62% yield (entry 9).

A plausible mechanism for the visible-light photoredox coupling reported herein is outlined in Scheme 1. As proposed by Okada8 for the fragmentation of N-(acyloxy)phthalimides, single-electron transfer from Ru(bpy)3+ to the tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalate, followed by homolytic cleavage of the N–O bond and subsequent decarboxylation generates alkoxycarbonyl radical 12. A second slower decarboxylation leads to the formation of tertiary radical 13,10,19 which after addition to an electron- deficient alkene provides α-acyl radical 14. Hydrogen atom abstraction from Hantzsch ester radical cation 10b would furnish the final product (14→7). An alternative pathway (not shown), involving reduction of α-acyl radical 14 to the corresponding enolate and subsequent protonation, could also lead to the formation of 7. While the presence of Hantzsch ester 10a is necessary to realize catalytic turnover, the role of the ammonium additive is not fully understood at this time. However, it could potentially serve to protonate intermediate radical anion 11 and also act as a source of BF4− to undergo anion exchange with [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 leading to the formation of the more soluble [Ru(bpy)3](BF4)2 complex.

Scheme 1.

In conclusion, we have developed a convenient method for the direct construction of quaternary carbons from tertiary alcohols by visible-light photoredox coupling of tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalate intermediates with electron-deficient alkenes. In three examples, in which the intermediate tertiary carbon radical is chiral and sterically biased, diastereoselection in forming the new quaternary carbon stereocenter was excellent. Additional synthetic applications of tert-alkyl N-phthalimidoyl oxalates, as well as mechanistic studies of their reactivity in photoredox-mediated processes, are currently under investigation and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the National Science Foundation (CHE1265964). NMR and mass spectra were determined at UC Irvine using instruments purchased with the assistance of NSF and NIH shared instrumentation grants. We thank Dr. Joseph Ziller and Dr. John Greaves, Department of Chemistry, UC Irvine, for their assistance with X-ray and mass spectrometric analyses.

Footnotes

Experimental details, characterization data, and CIF files for 6j and 7d. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Damm W, Giese B, Hartung J, Hasskerl T, Houk KN, Hüter; Zipse H. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4067. [Google Scholar]; Arnaud R, Postlethwaite H, Barone V. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:5913. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Giese B. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1983;22:753. [Google Scholar]; (b) Beckwith AL, Poole JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9489. doi: 10.1021/ja025730g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayen A, Koch R, Saak W, Haase D, Metzger JO. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12458. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For recent reviews that discuss the addition of carbon radicals to alkenes, see: Renaud P, Sibi MP. Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Vol. 2. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2001. Zard SZ. Radical Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Oxford; New York: 2003. Srikanth GSC, Castle SL. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:10377.Rowlands GJ. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:8603.

- 5.Barton DHR, Sas W. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:3419. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christoffers A Baro. Quaternary Stereocenters–Challenges and Solutions for Organic Synthesis. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For use of visible-light photoredox catalysis in complex natural product synthesis see: Schnermann MJ, Overman LE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:9576. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204977.For use of a tertiary halide as a radical precursor see: Furst L, Narayanam JMR, Stephenson CRJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:9655. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103145.

- 8.For the pioneering development of N-(acyloxy)phthalimides for forming carbon radicals, see: Okada K, Okamoto K, Morita N, Okubo K, Oda M. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9401.

- 9.For recent reviews, see: Tucker JW, Stephenson CRJ. J Org Chem. 2012;77:1617. doi: 10.1021/jo202538x.Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5322. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r.

- 10.(a) Barton DHR, Crich D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:757. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barton DHR, Crich D, Kretzschmar G. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1986:39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elimination is a serious complication,10b see also: Aggarwal VK, Angelaud R, Bihan D, Blackburn P, Fieldhouse R, Fonquerna SJ, Ford GD, Hynd G, Jones E, Jones RVH, Jubault P, Palmer MJ, Ratcliffe PD, Adams H. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 2001:2604.

- 12.Tertiary bromides and iodides are the most widely employed precursors of tertiary radicals.4,7b However, as a result of competing rearrangement and elimination reactions, these halides will not be available from many structurally complex tertiary alcohols.7a

- 13.Although many alcohol derivatives have found use in the deoxygenation of tertiary alcohols,14 to our knowledge there are only scattered reports of the bimolecular trapping of tertiary radicals generated from these precursors to construct quaternary carbons.10,15

- 14.McCombie SW, Motherwell WB, Tozer MJ. Org React. 2012;77:161. [Google Scholar]

- 15.For examples, see: Togo H, Fujii M, Yokoyama M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1991;64:57.Togo H, Matsubayashi S, Yamazaki O, Yokoyama M. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2816. doi: 10.1021/jo991715r.Blazejewski J–C;, Diter P, Warchol T, Wakselman C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:859.Sunazuka T, Yoshida K, Kojima N, Shirahata T, Hirose T, Handa M, Yamamoto D, Harigaya Y, Kuwajima I, Omura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:1459.

- 16.Excess methyl vinyl ketone contributes to diminished product yields by the addition of intermediate 14 (Scheme 3) to a second equivalent of methyl vinyl ketone. See reference 8 for similar observations.

- 17.Togo H, Yokoyama M. Heterocycles. 1990;31:437. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morikawa T, Washio Y, Harada S, Hanai R, Kayashita T, Nemoto H, Shiro M, Taguchi T. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1995:271. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simakov PA, Martinez FN, Horner JH, Newcomb M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:1226. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.