Abstract

Calmodulin regulation of CaV channels is a prominent Ca2+ feedback mechanism orchestrating vital adjustments of Ca2+ entry. The long-held structural correlate of this regulation has been Ca2+-bound calmodulin complexed alone with an IQ domain on the channel carboxy terminus. Here, however, systematic alanine mutagenesis of the entire carboxyl tail of an L-type CaV1.3 channel casts doubt on this paradigm. To identify the actual molecular states underlying channel regulation, we develop a structure-function approach relating the strength of regulation to the affinity of underlying calmodulin/channel interactions, by a Langmuir relation (iTL analysis). Accordingly, we uncover frank exchange of Ca2+-calmodulin to interfaces beyond the IQ domain, initiating substantial rearrangements of the calmodulin/channel complex. The N-lobe of Ca2+-calmodulin binds an NSCaTE module on the channel amino terminus, while the C-lobe binds an EF-hand region upstream of the IQ domain. This system of structural plasticity furnishes a next-generation blueprint for CaV channel modulation.

Calmodulin (CaM) regulation of the CaV1–2 family of Ca2+ channels ranks among the most consequential of biological Ca2+ decoding systems1,2. In this regulation, the Ca2+-free form of CaM (apoCaM) already preassociates with channels3–5, ready for ensuing Ca2+-driven modulation of channel opening. Upon elevation, intracellular Ca2+ binds to this indwelling CaM, driving conformational changes that enhance opening in some channels6–8 (positive-feedback ‘facilitation’), and inhibit opening in others9,10 (negative-feedback ‘inactivation’). Intriguingly, Ca2+ binding to the individual C- and N-terminal lobes of CaM can semiautonomously induce distinct components of channel regulation7,9,11, where the C-lobe responds well to Ca2+ entering through the channel on which the corresponding CaM resides (‘local Ca2+ selectivity’), and the N-lobe may in some channels require the far weaker Ca2+ signal from distant Ca2+ sources6,7,12–14 (‘global Ca2+ selectivity’). Such Ca2+ feedback regulation influences many biological functions1,15–17, and furnishes mechanistic lessons for Ca2+ decoding14. Indeed, CaM regulation of L-type (CaV1.2) channels strongly influences cardiac electrical stability15,18, and pharmacological manipulation of such regulation looms as a future antiarrhythmic strategy18,19.

Crucial for understanding and manipulating this CaM regulatory system is identification of the conformations that underlie such Ca2+ modulation. Figure 1a summarizes the currently accepted conceptual framework, with specific reference to L-type CaV1.3 channels for concreteness. Configuration E (‘empty’ of CaM) represents channels lacking preassociated Ca2+-free CaM (apoCaM). Such channels can open normally, but do not exhibit Ca2+/CaM-dependent inactivation (CDI) over the typical ~300-msec duration of channel-activity measurements20. Over this period, Ca2+/CaM from the bulk solution cannot appreciably access a channel in configuration E to produce CDI20–23. ApoCaM preassociation with configuration E yields channels in configuration A, where opening can also proceed normally, but subsequent CDI can now ensue. A thereby denotes channels that are ‘active’ and capable of CDI. Switching between configurations E and A occurs slowly (>10s of secs24), and almost exclusively involves apoCaM, because typical experiments only briefly activate Ca2+ channels every 20–30 secs. Thus, there is negligible exchange with configuration E during typical measurements of current. Regarding CDI, Ca2+ binding to both lobes of CaM yields configuration ICN (both C and N lobes of CaM engaged towards CDI), corresponding to a fully inactivated channel with strongly reduced opening2,25. As for intermediate configurations7,9,11,14,26, Ca2+ binding only to the C-lobe induces configuration IC, representing a C-lobe inactivated channel with reduced opening; Ca2+ binding only to the N-lobe yields an analogous N-lobe inactivated configuration (IN), also with reduced opening. Subsequent entry into configuration ICN likely involves cooperative interactions denoted by a λ symbol. Overall, CDI reflects redistribution from configuration A into IC, IN, and ICN. Of note, we exclude cases where one Ca2+ binds a lobe of CaM, because binding within lobes is highly cooperative27. Moreover, only one CaM is included, based on multiple lines of evidence22,23.

Figure 1. General schema for CaM regulation of representative L-type CaV1.3 channels.

(a) Primary configurations of CaM/channel complex with respect to CaM-regulatory phenomena (E, A, IC, IN, and ICN). Inset at far right, cartoon of main channel landmarks involved in CaM regulation, with only the pore-forming α1D subunit of CaV1.3 diagrammed. Ca2+-inactivation (CI) region, in the proximal channel carboxy terminus (~160 aa), contains elements potentially involved in CaM regulation. IQ domain (IQ), comprising the C-terminal ~30 aa of the CI segment, long proposed as preeminent for CaM/channel binding. Dual vestigial EF-hand (EF) motifs span the proximal ~100 aa of the CI module; these have been proposed to play a transduction role in channel regulation. Proximal Ca2+-inactivating (PCI) region constitutes the CI element exclusive of the IQ domain. NSCaTE on channel amino terminus of CaV1.2–1.3 channels may be the N-lobe Ca2+/CaM effector site. (b) Whole-cell CaV1.3 currents expressed in HEK293 cell, demonstrating CDI in the presence of endogenous CaM only. CDI observed here can reflect properties of the entire system diagrammed in a, as schematized by the stick-figure diagram at the bottom of b. Here and throughout, the vertical scale bar pertains to 0.2 nA of Ca2+ current (black); and the Ba2+ current (gray) has been scaled ~3-fold downward to aid comparison of decay kinetics, here and throughout. Horizonal scale bar, 100 ms. (c) Currents during overexpression of CaMWT, isolating the behavior of the diamond-shaped subsystem at bottom. (d) Currents during overexpression of CaM12, isolating C-lobe form of CDI. (e) Currents during overexpression of CaM34, isolating N-lobe form of CDI. (c–e) Vertical bar, 0.2 nA Ca2+ current. Timebase as in b.

The structural basis of this conceptual foundation is less certain, but has been dominated by an IQ-centric hypothesis, where an IQ domain, present on the carboxy termini of all CaV1–2 channels2 (Fig. 1a, far right, blue circle), serves as the dominant CaM binding locus on the channel. By this hypothesis, not only does this element comprise much of the preassociation surface for apoCaM4,5,20 (Fig. 1a, configuration A), it also constitutes the primary effector site2,5,7,9,10,25,28 for Ca2+/CaM rebinding to induce Ca2+ regulation (e.g., Fig. 1a, ICN). The predominance of the IQ-centric paradigm2 has prompted resolution of several crystal structures of Ca2+/CaM complexed with IQ-domain peptides of various CaV1–2 channels29–32.

Nonetheless, certain findings fit poorly with this viewpoint. Firstly, crystal structures of Ca2+/CaM complexed with wild-type and mutant IQ peptides of CaV1.2 indicate that a signature isoleucine in the IQ element is deeply buried within the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM, and that alanine substitution at this isoleucine negligibly perturbs structure30. Moreover, Ca2+/CaM affinities for analogous wild-type and mutant IQ peptides are nearly identical28. How then does alanine substitution at this well-encapsulated locus influence the rest of the channel to strongly disrupt functional regulation30? Secondly, in CaV1.2/1.3 channels, we have demonstrated that the effector interface for the N-lobe of Ca2+/CaM resides within an NSCaTE element of the channel amino terminus13,14,33 (Fig. 1a, far right), separate from the IQ element. Thirdly, analysis of the atomic structure of Ca2+/CaM bound to an IQ peptide of CaV2.1 channels hints that the C-lobe effector site also resides somewhere outside the IQ module31. In all, the long disconnect between challenges like these and IQ-centric theory represents a critical impasse in the field.

A major concern with prior IQ-domain analyses is that function was mostly characterized with only endogenous CaM present5,10,25,28,31. This regime is problematic because IQ-domain mutations could alter CaM regulation via perturbations at multiple steps within Fig. 1a, whereas interpretations mainly ascribe effects to altered Ca2+/CaM binding with an IQ effector site. Serious interpretive challenges thus include: (1) While the high apoCaM affinity of most wild-type channels4,20 renders configuration E unlikely (Fig. 1a), this may not hold true for mutant channels, just as observed for certain CaV1.3 splice variants20. Mutations weakening apoCaM preassociation could thereby reduce CDI by favoring configuration E (Fig. 1a, incapable of CDI), without affecting Ca2+/CaM binding. (2) Mutations that do weaken interaction with one lobe of Ca2+/CaM may have their functional effects masked by cooperative steps (λ in Fig. 1a).

This study systematically investigates the IQ-centric hypothesis, minimizing the above challenges by focusing on CaV1.3 channels, a representative L-type channel whose CDI is particularly robust and separable into distinct C- and N-lobe components11,13,14. These attributes simplify analysis as follows. For orientation, Fig. 1b illustrates the CDI of CaV1.3 channels expressed in HEK293 cells, with only endogenous CaM present. Strong CDI is evident from the rapid decay of whole-cell Ca2+ current (black trace), compared with the nearly absent decline of Ba2+ current (gray trace). Because Ba2+ binds negligibly to CaM34, the fractional decline of Ca2+ versus Ba2+ current after 300-ms depolarization quantifies the steady-state extent of CDI (Fig. 1b, right, CDI parameter). The CDI here reflects the operation of the entire Fig. 1a system, as schematized at the bottom of Fig. 1b. We can formally isolate the diamond-shaped subsystem lacking configuration E (Fig. 1c, bottom), by using mass action and strong overexpression of wild-type CaM (CaMWT). The resulting CDI (Fig. 1c) is indistinguishable from that with only endogenous CaM present (Fig. 1b), owing to the high apoCaM affinity of wild-type CaV1.3 channels. Full deconstruction of CDI arises upon strong coexpression of channels with a mutant CaM that only allows Ca2+ binding to its C-terminal lobe9 (Fig. 1d, CaM12). With reference to Fig. 1a, this maneuver depopulates configuration E by mass action, and forbids access into configurations IN and ICN. Thus, the isolated C-lobe component of CDI11,14 is resolved (Fig. 1d), with its signature rapid timecourse of current decay. Importantly, this regime avoids interplay with cooperative λ steps in Fig. 1a. Likewise, strongly coexpressing mutant CaM exhibiting Ca2+ binding to its N-lobe alone9 (CaM34) isolates the slower N-lobe form of CDI11,14 (Fig. 1e), with attendant simplifications. Thus armed, we here exploit selective monitoring of CaV1.3 subsystems (Fig. 1b–e), combined with alanine scanning mutagenesis of the entire carboxyl tail of CaV1.3 channels. In so doing, we argue against the IQ-centric paradigm, and propose a new framework for the CaM regulation of Ca2+ channels.

RESULTS

iTL analysis of CaM/channel regulation

Identifying channel effector interfaces for Ca2+/CaM is challenging. The main subunit of CaV channels alone spans about two-thousand amino acids or more; and peptide assays indicate that Ca2+/CaM can bind to multiple segments of uncertain function25,35–39. Even if mutating these segments alters CaM regulation, the observed functional effects could reflect perturbations of apoCaM preassociation, Ca2+/CaM binding, or transduction. To address these challenges, we initially consider an expanded conceptual layout believed valid for either isolated N- or C-lobe CDI14 (Fig. 2a), then deduce from this arrangement a simple quantitative analysis to identify bona fide effector interfaces. An apoCaM lobe begins prebound to a channel preassociation surface (state 1). Ca2+ binding to CaM in this prebound state is considered rare14,40. However, after apoCaM releases (state 2), it may bind Ca2+ to produce Ca2+/CaM (state 3), or return to state 1. The transiently dissociated lobe of CaM (state 2 or 3) remains within a channel alcove over the usual timescale of CaM regulation (≤ seconds). Finally, Ca2+/CaM binds a channel effector site (state 4, square pocket), ultimately inducing regulation via transduction to state 5. Emergent behaviors of this scheme rationalize local and global Ca2+ selectivities, as argued previously14.

Figure 2. Probing functionally relevant CaM regulatory interactions via iTL analysis.

(a) Isolated C- or N-lobe regulatory system (denoted by stick-figure diagrams on left) can be coarsely represented by a five-state scheme on right. A single lobe of apoCaM begins preassociated to channel (state 1). Following disassociation (state 2), CaM may bind two Ca2+ ions (state 3, black dots). Ca2+/CaM may subsequently bind to channel effector site (state 4). From here, transduction step leads to state 5, equivalent to CDI. Association constant for lobe of apoCaM binding to preassociation site is ɛ; whereas γ1 and γ2 are association constants for respective transitions from states 3 to 4, and states 4 to 5. (b) Unique Langmuir relation (Eq. 1) that will emerge upon plotting channel CDI (defined Fig. 1b, right) as a function of Ka,EFF (association constant measured for isolated channel peptide), if Ka,EFF is proportional to one of the actual association constants in the scheme as in a. Black symbols, hypothetical results for various channel/peptide mutations; green symbol, hypothetical wild type. (c) Predicted outcome if peptide association constant Ka,EFF has no bearing on association constants within holochannels. (d) Outcome if mutations affect holochannel association constants, but not peptide association constants. (e) Outcome if mutations affect holochannel association constant(s) and peptide association constant, but in ways that are poorly correlated.

Despite the multiple transitions present even for this reduced CDI subsystem (Fig. 2a, left schematics), a straightforward relationship emerges that will aid detection of Ca2+/CaM interfaces on the channel, as follows. Suppose we can introduce point alanine mutations into the channel that selectively perturb the Ca2+/CaM binding equilibrium association constant γ1 (Fig. 2a). Also suppose we can measure Ca2+/CaM binding to a corresponding channel peptide, and the affiliated association constant Ka,EFF is proportional to γ1 in the channel. It then turns out that our metric of inactivation (CDI in Fig. 1b) will always be given by the Langmuir function

| (1) |

where CDImax is the value of CDI if Ka,EFF becomes exceedingly large, and Λ is a constant comprised of other association constants in the layout (Supplementary Note 1). Figure 2b plots this function, where the green symbol marks a hypothetical wild-type-channel position, and mutations should create data symbols that decorate the remainder of the curve. Importantly, the requirement that peptide Ka,EFF need only be proportional to (not equal to) holochannel γ1 increases the chances that tagged peptides may suffice to correlate with holochannel function. Additionally, Eq. 1 will hold true only if these two suppositions are satisfied (Supplementary Note 2). For example, if mutations alter two transitions within the holochannel, a function with different shape will result. Alternatively, if mutations change the peptide interaction with Ca2+/CaM (Ka,EFF), but not any of the actual association constants within the channel, the outcome in Fig. 2c will emerge. In this case, though the channel peptide can bind Ca2+/CaM in isolation, this reaction has no bearing on transitions within the intact holochannel (Fig. 2a). By contrast, Fig. 2d diagrams a scenario where mutations actually do affect transition(s) governing CDI within the holochannel, yet altogether fail to perturb Ca2+/CaM binding to a peptide segment of the channel. It is also possible that mutations could affect transition(s) governing CDI within the holochannel, but in ways that are uncorrelated with mutational perturbations of Ca2+/CaM binding to a corresponding peptide segment (Fig. 2e). The red symbol denotes a specific subset of this scenario, where a mutation affects transition(s) within the holochannel so as to enhance CDI, whereas the same mutation produces uncorrelated diminution of Ca2+/CaM binding to a peptide segment of the channel. Yet other deviations from Eq. 1 are possible, including those arising from the existence of effector sites beyond our alanine scan (Supplementary Note 3). Importantly, these outcomes will pertain regardless the size and complexity of the scheme in Fig. 2a (Supplementary Note 4). Because of this generality, we term the analysis individually Transformed Langmuir (iTL) analysis.

Given this insight, we undertook alanine-scanning mutagenesis of CaV1.3 channel domains, and screened electrophysiologically for altered CaM regulatory hotspots. In parallel, we introduced hotspot mutations into peptides overlapping scanned regions, and estimated Ka,EFF of potential CaM binding. For this purpose, we utilized live-cell FRET two-hybrid assays3,4,41, which have the resolution and throughput for the task. If such binding truly reflects holochannel function, then CDI should vary with Ka,EFF as a Langmuir function (Eq. 1, Fig. 2b). By contrast, if Ka,EFF changes in a manner unrelated to holochannel CDI, data would diverge from Eq. 1 (Fig. 2c–e, or otherwise). CaM effector interfaces could thus be systematically resolved.

iTL analysis of IQ domain as Ca2+/CaM effector site

We first addressed whether the CaV1.3 IQ domain serves as a Ca2+/CaM effector site for CDI, as IQ-centric theory postulates. Single alanines were substituted at each position of the entire IQ domain of CaV1.3 channels, whose sequence appears atop Fig. 3a with the signature isoleucine bolded at position ‘0.’ Naturally occurring alanines were changed to threonine. CDI of these mutants was then characterized for the isolated N- and C-lobe CDI subsystems described above (Fig. 3a, b, left schematics), thus minimizing potential complications from diminished preassociation with apoCaM (Fig. 1a, configuration E), or masking of CDI effects by cooperative λ steps (Fig. 1a). Whereas little deficit in N-lobe CDI was observed (Fig. 3a), C-lobe CDI was strongly attenuated by alanine substitutions at I[0]A (Fig. 3b, red bar, exemplar traces) and nearby positions (rose). To test for correspondence between reductions in C-lobe CDI and altered Ca2+/CaM binding, we performed FRET 2-hybrid assays of Ca2+/CaM binding to alanine-substituted IQ peptides, with substitutions encompassing sites associated with the strongest CDI effects (Fig. 3b, red and rose bars). Hatched bars denote additional sites chosen at random. The left aspect of Fig. 3c cartoons the FRET interaction partners, and the right portion displays the resulting binding curve for the wild-type IQ peptide (Fig. 3c, right, black). FR-1 is proportional to FRET efficiency, as indicated by the efficiency EA scale bar on the right. Dfree is the free concentration of donor-tagged molecules (CFP–CaM), where 200 nM ~6100 Dfree units4,42. At odds with a Ca2+/CaM effector role of the IQ domain, the binding curve for the I[0]A substitution (Fig. 3c, right, red) resembled that for the wild-type peptide (black), whereas C-lobe CDI was strongly decreased (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c (middle) displays a bar-graph summary of the resulting association constants (Ka,EFF); the wild-type value is shown as a dashed green line, and that for I[0]A as a red bar (Supplementary Note 5). If the IQ domain were the effector site for the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM, C-lobe CDI over various substitutions should correlate with association constants according to Eq. 1 (Supplementary Notes 1 and 6). However, plots of our data markedly deviate from such a relation (Fig. 3e), much as in Fig. 2e. The green symbol denotes the wild-type IQ case. Likewise, plots of N-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF deviated from a Langmuir (Fig. 3d), much as in Fig. 2c. These outcomes fail to support the IQ domain as an effector site for either lobe of Ca2+/CaM. The actual role of the IQ domain in CDI will be explored later in Fig. 6.

Figure 3. Inconsistencies with IQ domain role as Ca2+/CaM effector site.

(a) No appreciable deficit in isolated N-lobe CDI upon point alanine substitutions across the IQ domain (sequence at top with bolded isoleucine at ‘0’ position). Left, corresponding subsystem schematic. Middle, bar-graph summary of CDI metric, as defined in Fig. 1b. Bars, mean ± SEM for ~6 cells each. Green dashed line, wild-type profile; red bar, I[0]A; blue symbol in all panels, Y[3]D. Right, exemplar currents, demonstrating no change in N-lobe CDI upon I[0]A substitution. Horizontal scale bar, 100 ms; vertical scale bar, 0.2 nA Ca2+ current. Red, Ca2+ current; gray, Ba2+ current. (b) Isolated C-lobe CDI (corresponding subsystem schematized on left) exhibits significant attenuation by mutations surrounding the central isoleucine (colored bars). Format as in a. I[0]A shows the strongest attenuation (red bar and exemplar currents at right). Bars average ~5 cells ± SEM . Dashed green line, wild-type profile. Timebase as in b; vertical scale bar, 0.2 nA Ca2+ current . (c) Bar-graph summary of association constants (Ka,EFF = 1 / Kd,EFF) for Ca2+/CaM binding to IQ, evaluated for constructs exhibiting significant effects in b (colored bars, with I[0]A in red), or chosen at random (hashed in b). Error bars, nonlinear standard-deviation estimates. FRET partners schematized on the left, and exemplar binding curves on the right for I[0]A (red) and wild-type (black). Symbols average ~7 cells. Smooth curve fits, 1:1 binding model. Calibration to efficiency EA = 0.1, far right vertical scale bar. Horizontal scale bar corresponds to 100 nM. (d) Plots of N-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF deviate from Eq. 1, much as in Fig. 2c. Green, wild type; red, I[0]A; blue, Y[3]D. (e) Plots of C-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF also diverge from Langmuir, as in Fig. 1e. This result further argues against the IQ per se acting as an effector site for the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM. Symbols as in d. (d, e) Y[3]D (blue symbol, CDI mean of 4 cells) yields poor Ca2+/CaM binding, but unchanged CDI. Supplementary Note 7, further FRET data.

Figure 6. Role of IQ domain in C-lobe CDI.

(a) Cartoon depicting putative binding interaction between IQ domain and PCI segment, which is also required for C-lobe CDI. (b) Bar-graph summary of C-lobe CDI measured for alanine scan of IQ domain, reproduced from Fig. 3b. Strongest CDI reduction for I[0]A mutant (red), followed closely by loci affiliated with rose and blue bars underneath gray dashed-line. Dashed-green line, wild-type. (c) Association constants Ka,EFF determined for 33-FRET binding between IQ domain and PCI region (partners diagrammed at left), under elevated levels of Ca2+. Wild-type profile, green dashed line. Bars, Ka,EFF for mutants with strongest effects (colored bars in b) or chosen at random (hashed bars in b). Error bars, nonlinear standard deviation estimates. (d) Exemplar 33-FRET binding curves for IQ/PCI interaction. Each symbol, mean ± SEM of ~8 cells. Absent Ca2+, the IQ domain associates only weakly with the PCI region (gray). However, elevated Ca2+ greatly enhances binding (black). (e) 33-FRET binding curves for I[0]A (red) and Q[1]A (blue) mutations under elevated Ca2+. Each symbol, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. Fit for wild type IQ/PCI interaction reproduced from d in black. (f) Plotting C-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF under elevated Ca2+ unveils a well-resolved Langmuir relation. WT (green), I[0]A (red), and Q[1]A (blue).

To undertake a still more stringent test, we investigated a Y[3]D construct, based on a prior analogous mutation in CaV2.1 that intensely diminished Ca2+/CaM affinity31. Indeed, the Y[3]D substitution in CaV1.3 resulted in a large 13.5-fold decrement in Ka,EFF (Fig. 3c, blue symbol). However, there was no change in C- or N-lobe CDI (Fig. 3a, b, blue symbols; Supplementary Note 7). These data deviated yet more strongly from a Langmuir (blue symbols, Fig. 3d, e), arguing further against the IQ domain as a Ca2+/CaM effector site.

NSCaTE element upheld as effector site for N-lobe of Ca2+/CaM

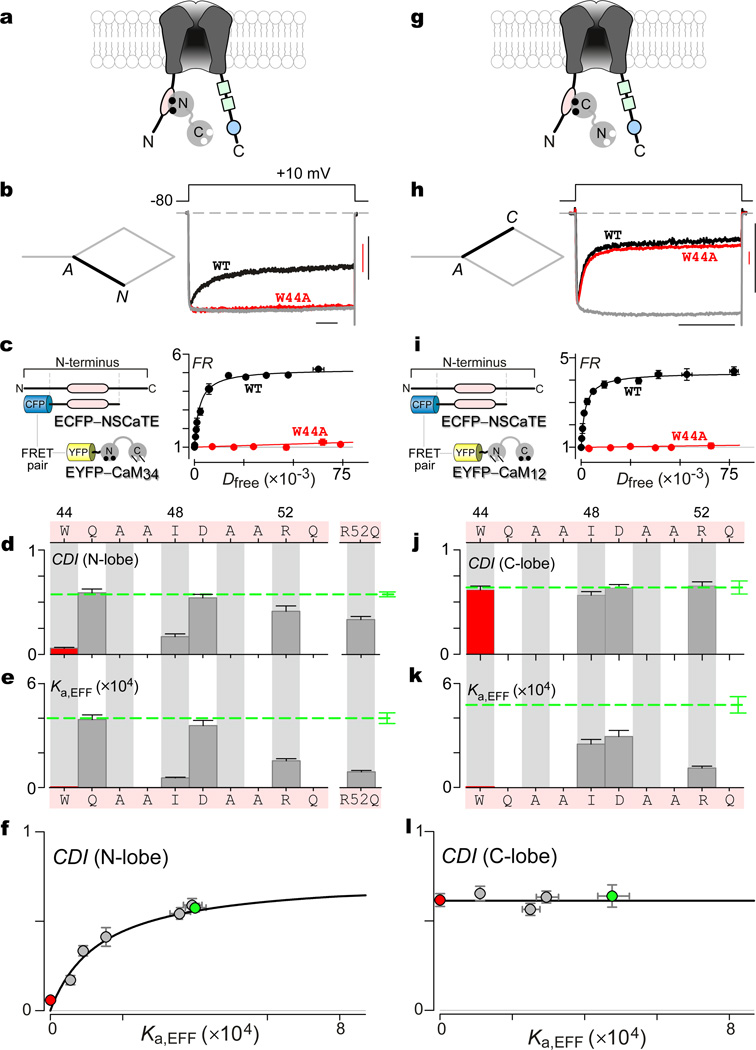

Absent a positive outcome for iTL analysis of the IQ domain (i.e., Fig. 2b), we turned to the amino-terminal NSCaTE module (Fig. 4a, oval), previously proposed as an effector site for N-lobe CDI13,14. For reference, Fig. 4b displays the wild-type CaV1.3 profile for N-lobe CDI. Single alanines were substituted across the NSCaTE module (Fig. 4d, top), at residues that were not originally alanine. The bar-graph summary below (Fig. 4d) indicates strongly diminished N-lobe CDI upon alanine substitution at three residues, previously identified as critical13,14 (W[44]A, I[48]A, and R[52]A). For comparison, the wild-type level of CDI is represented by the green dashed line and affiliated error bars. W[44]A featured the strongest CDI decrement, as shown by the Ca2+ current (Fig. 4b, red trace) and population data (Fig. 4d, red bar). To pursue iTL analysis, we characterized corresponding binding curves between NSCaTE and Ca2+/CaM34 FRET pairs (Fig. 4c, left; Supplementary Note 8). The wild-type pairing exhibited a well-resolved binding curve with Ka,EFF = 4×10−4 Dfree−1 units (Fig. 4c, right, black), whereas the W[44]A variant yielded a far lower affinity with Ka,EFF ~0 (red). A summary of binding affinities is shown for this and additional mutations within NSCaTE in Fig. 4e (Supplementary Note 9), where the dashed-green line signifies the wild-type profile. The crucial test arises by plotting N-lobe CDI as a function of Ka,EFF, which resolves the Langmuir relation in Fig. 4f. For reference, wild type is shown in green, and W[44]A in red. The particular formulation of Eq. 1 for this arrangement is given in Supplementary Note 1. Hence, iTL analysis does uphold NSCaTE as a predominate effector site for N-lobe CDI, as argued before by other means13,14. By contrast, analysis of C-lobe CDI (Fig. 4g-k; Supplementary Note 10) reveals deviation from Eq. 1 (Fig. 4l), much as in Fig. 2c. Thus, NSCaTE mutations have little bearing on C-lobe CDI of the holochannel, though such mutations affect Ca2+/CaM12 binding to an isolated NSCaTE peptide.

Figure 4. iTL analysis of Ca2+/CaM effector role of NSCaTE module of CaV1.3 channels.

(a) Cartoon depicting NSCaTE as putative effector interface for N-lobe of Ca2+/CaM. (b) Exemplar CaV1.3 whole-cell currents exhibiting robust isolated N-lobe CDI, as seen from the rapid decay of Ca2+ current (black trace). Corresponding stick-figure subsystem appears on the left. W[44]A mutation abolishes N-lobe CDI, as seen from the lack of appreciable Ca2+ current decay (red trace). Gray trace, averaged Ba2+ trace for wild-type (WT) and W[44]A constructs. Horizontal scale bar, 100 ms; vertical scale bar, 0.2 nA Ca2+ current (red, W44A; black, WT). (c) FRET 2-hybrid binding curves for Ca2+/CaM34 and NSCaTE segment, with FRET partners schematized on the left. Wild-type pairing (WT) in black; W[44]A mutant pairing in red. Each symbol, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. (d) Bar-graph summary of N-lobe CDI for NSCaTE mutations measured after 800-ms depolarization, with NSCaTE sequence at the top, as numbered by position within CaV1.3.. Data for W[44]A in red; dashed green line, wild type. Bars, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. (e) Association constants (Ka,EFF = 1 / Kd,EFF) for Ca2+/CaM34 binding to NSCaTE module evaluated for constructs exhibiting significant effects in panel d. Error bars, nonlinear standard deviation estimates. Data for W[44]A in red; dashed green line, wild type. (f) Plotting N-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF uncovers a Langmuir, identifying NSCaTE as functionally relevant effector site. W[44]A in red; wild type in green. (g-l) iTL fails to uphold NSCaTE as effector site for C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM. Format as in a–f. (h, j) C-lobe CDI at 300 ms, unchanged by NSCaTE mutations. Bars in j, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. (i, k) Changes in Ka,EFF of NSCaTE module for Ca2+/CaM12 via 33-FRET. Each symbol in i, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. (l) C-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF deviates from Langmuir, as in Fig. 2c.

Identification of the C-lobe Ca2+/CaM effector interface

Satisfied by proof-of-principle tests of the iTL approach, we turned to identification of the as-yet-unknown effector site for the C-lobe form of CDI. Our screen focused upon the entire carboxy tail of CaV1.3 channels upstream of the IQ domain (Fig. 5a, PCI domain), because switching these carboxy-terminal segments in chimeric channels sharply influences this type of CDI31,43. For completeness, we initially characterized isolated N-lobe CDI for mutations throughout the PCI, and found no appreciable decrement from wild-type levels (Fig. 5b, e; Supplementary Note 12), as expected. Gaps indicate nonexpressing configurations. By contrast, for isolated C-lobe CDI, the sharp diminution of CDI upon LGF→AAA substitution (Fig. 5c, f, red) exemplifies just one of many newly discovered ‘hotspot’ loci residing in the PCI midsection (Fig. 5f, rose and red; Supplementary Note 12). As a prelude to iTL analysis, we determined the binding of Ca2+/CaM to the PCI element (Fig. 5g, left cartoon), and indeed the LGF substitution weakens interaction affinity (Fig. 5d). Likewise, binding of the isolated C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM to PCI was similarly attenuated by the LGF mutation (Supplementary Note 11), arguing explicitly for disruption of a C-lobe interface. Additionally, for loci demonstrating the strongest reduction in C-lobe CDI (Fig. 5f, rose and red), corresponding Ca2+/CaM affinities were determined to also attenuate Ka,EFF (Fig. 5g; Supplementary Notes 11–12). Importantly, graphing C-lobe CDI versus binding affinity strikingly resolves a Langmuir relation (Fig. 5i), furnishing compelling evidence that the PCI midsection comprises an effector interface for the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM. The green symbol corresponds to wild type, and the red datum to the LGF mutant. Supplementary Note 1 specifically formulates Eq. 1 for this case. As expected, plots of N-lobe CDI versus binding affinity deviate from a Langmuir (Fig. 5h), much as in Fig. 2c, e. Overall, the impressive mirror-like inversion of results for NSCaTE (Fig. 4f, l) and PCI (Fig. 5h, i) underscores the considerable ability of iTL analysis to distinguish between effector sites of respective N- and C-lobe CDI.

Figure 5. iTL analysis of PCI segment as C-lobe Ca2+/CaM effector interface.

(a) Channel cartoon depicting PCI segment as putative effector site for C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM. (b) Isolated N-lobe CDI for wild type (WT) and LGF→AAA (LGF) mutant channels. Ca2+ current for WT in red, and for LGF in red. Gray, averaged Ba2+ trace. Horizontal scale bar, 100 ms; vertical scale bar, 0.2 nA Ca2+ current (red, LGF; black, WT). (c) Isolated C-lobe CDI for WT and LGF mutant channels, indicating strong CDI attenuation by LGF mutation. Format as in b. (d) FRET 2-hybrid binding curves for Ca2+/CaM pitted against PCI segments, for WT (black) and LGF (red). Each symbol, mean ± SEM from ~ 9 cells. (e) Bar-graph summary confirming no appreciable reduction of isolated N-lobe CDI, over all alanine scanning mutants across the PCI region (sequence at the top). Schematic of corresponding system under investigation at the left. Green dashed line, wild type; red, LGF mutant; gaps, nonexpressing configurations. Bars, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. (f) Bar-graph summary, C-lobe CDI for alanine scan of PCI. Red bar, LGF→AAA mutant showing strong CDI reduction. Rose bar, other loci showing substantial CDI reduction. Hashed, randomly chosen loci for subsequent FRET analysis below. Bars, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. (e, f) CDI decrease for YLT cluster (Fig. 5e, f) reflects reduced Ca2+ entry from 30-mV depolarizing shift in activation, not CDI attenuation per se. Shifts for all other loci were at most ±10 mV (not shown). (g) Association constants for Ca2+/CaM binding to PCI region, with FRET partners as diagrammed on the left. Green dashed line, wild-type profile. PCI mutations yielding large C-lobe CDI deficits were chosen for FRET analysis (red and rose in f), as well as those chosen at random (hashed in f). Error bars, nonlinear estimates of standard deviation. (h) Plots of N-lobe CDI versus Ka,EFF for Ca2+/CaM binding to PCI deviated from Langmuir. Red, LGF; green, WT. (i) Alternatively, plotting C-lobe CDI revealed Langmuir relation, supporting PCI as C-lobe Ca2+/CaM effector site. Symbols as in h.

C-lobe CDI also requires IQ domain interaction with the PCI element

Though the IQ domain alone does not appear to be an effector site for Ca2+/CaM (Fig. 3), alanine substitutions in this element nonetheless attenuated C-lobe CDI7,10,11,28,31, a result reproduced for reference in Fig. 6a, b. Might the departure of Ca2+/CaM to NSCaTE (Fig. 4) and PCI elements (Fig. 5) then allow the IQ domain to rebind elsewhere, in a manner also required for C-lobe CDI? Thus viewed, IQ-domain mutations could diminish C-lobe CDI by weakening this rebinding, but in a way that correlates poorly with IQ-peptide binding to Ca2+/CaM in isolation. Because C-lobe CDI can be conferred to CaV2 channels by substituting PCI and IQ elements from CaV131,43, might the requisite rebinding involve association between these very elements?

Initially disappointing was the existence of only low affinity binding between IQ and PCI modules (Fig. 6c, left cartoon; Fig. 6d, gray) under conditions of resting intracellular calcium3. By contrast, under elevated Ca2+, robust interaction between the same IQ/PCI FRET pair was observed, with Ka-PCI–IQ = 4.35 × 10−5 Dfree units−1 (Fig. 6d, black). In fact, this Ca2+-dependent interaction accords well with a role in triggering CDI, and likely arises from a requirement for Ca2+/CaM to bind the PCI domain before appreciable IQ association occurs (Supplementary Note 13). Beyond mere binding, however, functionally relevant interaction would be decreased by the same IQ-domain mutations that reduced C-lobe CDI. In this regard, IQ peptides bearing I[0]A or Q[1]A substitutions actually demonstrated strong and graded reductions in affinity (Fig. 5e, respective red and blue symbols), coarsely matching observed deficits in C-lobe CDI (Fig. 5b). Figure 5c summarizes the results of these and other FRET binding assays (Supplementary Note 14), performed for loci with the strongest effects on C-lobe CDI (Fig. 6b, colored bars under dashed-gray threshold). With these data, quantitative iTL analysis could be undertaken, where the presumed CDI transition in question would be the γ2 transduction step in Fig. 2a, and the relevant form of Eq. 1 is specified in Supplementary Note 15. Remarkably, plotting C-lobe CDI (Fig. 6b) versus IQ/PCI binding affinity (Fig. 6c) indeed resolves a Langmuir (Fig. 6f). Thus, C-lobe CDI likely requires a tripartite complex of IQ, PCI, and C-lobe Ca2+/CaM (Fig. 6a).

ApoCaM preassociation within the PCI domain

Having explored Ca2+/CaM, we turned to apoCaM interactions. Elsewhere42 we have shown that apoCaM preassociates with a surface that at least includes2,4,5,20 the IQ element. Furthermore, homology modeling42 of a related apoCaM/IQ structure for NaV channels44,45 suggests that the CaV1.3 IQ module interacts with the C-lobe of apoCaM. Might the N-lobe of apoCaM then bind the PCI domain (Fig. 7a)? If so, then our earlier PCI mutations could have weakened N-lobe apoCaM interaction, and potentially diminished CDI by favoring configuration E channels (Fig. 1a, incapable of inactivation). This effect would not have been apparent thus far, because we invariably overexpressed CaM. However, with only endogenous wild-type CaM present in Fig. 7e, CDI reflects the operation of a system that includes configuration E (left schematic), and the observed CDICaMendo is indeed strongly attenuated by mutations at many loci (rose and red bars).

Figure 7. Footprint of apoCaM preassociation with the PCI segment.

(a) Channel cartoon depicting apoCaM preassociated with the CI region, with C-lobe engaging IQ domain, and N-lobe associated with PCI region. (b) Whole-cell currents for TVM→AAA mutant in the PCI segment (Ca2+ in red; Ba2+ in gray), with only endogenous CaM present. Horizontal scale bar, 100 ms; vertical scale bar, 0.2 nA Ca2+ current. (c) Overexpressing CaMWT rescues CDI for TVM→AAA mutation, suggesting that PCI region harbors an apoCaM preassociation locus. Format as in b. (d) 33-FRET binding curves show strong apoCaM binding to CI region. Wild type (WT) in black; TVM→AAA in red. Each symbol, mean ± SEM of ~7 cells. (e) Bar-graph summary of CDI with only endogenous CaM present (CDICaMendo), across alanine scan of PCI region. TVM→AAA (red) shows strongest effect, with rose colored bars also showing appreciable CDI reduction. Bars, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. Left, schematic of relevant CaM subsystem. (f) Bar-graph summary of CDI rescue upon overexpressing CaMWT (CDICaMhi), for mutations showing significant loss of CDI (colored bars in e), or chosen at random (hashed bars in e). Bars, mean ± SEM of ~5 cells. Corresponding subsystem of regulation on the left. (g) Bar-graph summary of Ka,EFF for apoCaM binding to CI region, with partners as sketched on the left. Data obtained for nearly all mutants with significant CDI reduction (colored in e), and for some mutants chosen at random (hashed in e). Error bars, nonlinear estimates of standard deviation. (h) iTL analysis confirms role of PCI as functionally relevant apoCaM site. Plotting CDICaMendo/CDICaMhi (e and f) versus Ka,EFF for apoCaM/CI binding uncovers well-resolved Langmuir relation. TVM→AAA, red; WT, green. (i) Overlaying like data for IQ-domain analysis presented elsewhere42 (blue symbols here) displays remarkable agreement, consistent with the same apoCaM binding both PCI and IQ domains. Deep blue symbols, A[−4], I[0], F[+4] hotspots for apoCaM interaction with IQ element.

We tested for decreased preassociation as the basis of this effect, by checking whether CDI resurged upon strongly overexpressing wild-type CaM (CaMWT). This maneuver should act via mass action to eliminate CaM-less channels20, restrict channels to the subsystem on the left of Fig. 7f, and restore CDI. For all loci demonstrating appreciable reduction of CDICaMendo (Fig. 7e, rose and red), CDI was measured under strongly overexpressed CaMWT (CDICaMhi), as summarized in Fig. 7f. As baseline, we confirmed that elevating CaMWT hardly affected CDI of wild-type channels (compare wild-type, dashed-green lines in Fig. 7e, f). The high apoCaM affinity of wild-type channels renders configuration E channels rare, even with only endogenous apoCaM present20. By contrast, the TVM mutant exhibits an impressive return of CDI upon elevating CaMWT (Fig. 7b, c), as do many other mutants (Fig. 7f; Supplementary Note 16). Critically, scrutiny of the underlying configurations (Figs. 7e and 7f, left) reveals that CDICaMendo = CDICaMhi · Fb, where Fb is the fraction of channels prebound to apoCaM with only endogenous CaM present. This relation holds true, even with a residual CDICaMhi shortfall compared to wild type (e.g., Fig. 7f, LGF). This is so because a CDICaMhi deficit mirrors changes in the diamond subsystem of Fig. 7f (left), which are identically present in CDICaMendo measurements (Fig. 7e).

Thus aware, we tested whether apoCaM binding to the entire CI domain (spanning IQ and PCI modules) mirrors resurgent CDI (Fig. 7g, left cartoon; Supplementary Note 17). The wild-type pairing showed robust interaction with Ka,EFF = 2.5 × 10−4 Dfree units−1 (Fig. 7d, black; Fig. 7g, green dashed line). By contrast, the TVM pairing, corresponding to strong resurgent CDI (Fig. 7b, c), exhibited far weaker affinity (Fig. 7d, g, red; Ka,EFF = 0.13 × 10−4 Dfree units−1). Figure 7g tallies the graded decrease of Ka,EFF for these and other pairings (Supplementary Note 16).

Most rigorously, if PCI contacts indeed mediate apoCaM preassociation, then plotting CDICaMendo / CDICaMhi (= Fb) versus the Ka,EFF for apoCaM/CI interaction (Fig. 7g) should decorate a Langmuir relation (Supplementary Note 18). Indeed, just such a relation (Fig. 7h) is resolved (Fig. 7e–g), arguing that the N-lobe of apoCaM interfaces with corresponding PCI loci. Notably, this relation is identical to that reported elsewhere for IQ mutations on the same CI module42. Figure 7i explicitly overlays PCI and IQ data (in blue), and this striking resolution of a single Langmuir accords with one and the same apoCaM binding PCI and IQ domains.

DISCUSSION

These experiments fundamentally transform the prevailing molecular view of CaM regulation of Ca2+ channels. The field has long been dominated by an IQ-centric scheme2,5,7,9,10,25,28, wherein indwelling apoCaM begins preassociated with a carboxy-terminal IQ domain, and remains bound to this element upon CaM interaction with Ca2+. Here, our new proposal establishes substantial exchange of CaM to alternate effector loci (Fig. 8a). ApoCaM preassociates with an interface that includes, but is not limited to the IQ domain (configuration A): the C-lobe binds the IQ (cyan circle), and the N-lobe binds the central midsection of the PCI (green box). Ca2+ binding to the N-lobe yields configuration IN, wherein this lobe binds the NSCaTE module on the channel amino terminus (pink oval) to trigger N-lobe CDI. Ensuing Ca2+ binding to the C-lobe induces configuration ICN, with C-lobe binding the proximal PCI midsection (green square), and IQ engagement25. If Ca2+ only binds the C-lobe, the system adopts configuration IC, corresponding to C-lobe CDI. Ultimately, Ca2+/CaM exchange to effector loci diminishes opening, perhaps via allosteric coupling of carboxy-tail conformation to a contiguous IVS6 segment implicated in activation46,47 and inactivation48. Only a single CaM is present22,23 (Supplementary Note 17).

Figure 8. New view of CaM regulatory configurations of CaV1.3 channels.

(a) Molecular layout of configurations A, IC, IN, and ICN for conceptual scheme in Fig. 1a. ApoCaM preassociates with CI region: C-lobe articulates IQ domain, and N-lobe engages the PCI segment. Once Ca2+ binds CaM, the N-lobe of Ca2+/CaM departs to NSCaTE on channel amino terminus, eliciting N-lobe CDI (IN). Alternatively, the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM migrates to PCI segment, recruiting IQ domain to tri-partite complex (IC). Finally, ICN corresponds to channel that has undergone both N- and C-lobe CDI. (b) De novo model of CaV1.3 CI region docked to apoCaM (PCI region: green; IQ domain: blue). ApoCaM hotspots (Fig. 6e–g) in red. C-lobe of apoCaM contacts IQ, while N-lobe binds EF-hand region. (c) Left, atomic structure of NSCaTE bound to N-lobe of Ca2+/CaM (2LQC33). NSCaTE peptide in tan; and N-lobe Ca2+/CaM in cyan. Ca2+, yellow. N-lobe CDI hotspots on NSCaTE in red. Right, de novo model of tripartite IQ-PCI-Ca2+/CaM complex (PCI region, green; IQ domain, blue). C-lobe CDI hotspots in red for both PCI and IQ domains.

The structures of many of these configurations are presently unknown, but ab initio and homology modeling here confirms the plausibility of these configurations. Concerning the apoCaM/channel complex, Figure 8b displays a homology model of the C-lobe complexed with the IQ domain42 (blue), based on an analogous atomic structure from NaV channels44,45. Key IQ-domain hotspots for apoCaM preassociation (red) are rationalized by this model42. To portray the N-lobe as shown in Fig. 8b, we utilized ab initio structural prediction of the CI domain with the Rosetta package49 (Supplementary Note 19), yielding a PCI domain (green) with two vestigial EF hands, and a protruding helix (‘preIQ’ subelement). The EF-hand module (EF) resembles the structure of a homologous segment of NaV channels50,51, and a helical segment has been resolved in atomic structures of analogous CaV1.2 segments36,37. Reassuringly, N-lobe apoCaM hotspots adorn the surface of this PCI model (red coloration), within the more C-terminal of two EF hands. Accordingly, we appose the atomic structure of the N-lobe (1CFD) to this segment of the PCI model, initially using a shape-complementarity docking algorithm52 (PatchDock), followed by refinement with docking protocols of Rosetta (Supplementary Note 20). Of note, the configuration of the N-lobe explains the outright enhancement of N-lobe CDI by PCI mutations in the region of putative N-lobe contact (compare Figs. 5e and 7e, GKL through TLF). Weakening channel binding to the N-lobe (Fig. 2a, state 1) would, through connection to other states, increase state 5 occupancy, thereby boosting N-lobe CDI (Supplementary Note 21). By contrast, no N-lobe CDI enhancement was observed for IQ substitutions at the central isoleucine (I[0]) and downstream42, consistent with IQ binding the C-lobe of apoCaM.

Figure 8c displays a model of Ca2+/CaM complexed with the channel. The N-lobe bound to NSCaTE is an NMR structure33, and functional N-lobe CDI hotspots correspond well with intimate contact points (red). C-lobe CDI hotspots also adorn the surface of the upstream EF-hand region of an alternative ab initio model of the PCI (Fig. 8c, red; Supplementary Note 19). The IQ domain and atomic structure of the C-lobe of Ca2+/CaM (3BXL) were then computationally docked (Supplementary Note 22), yielding a rather canonical CaM/peptide complex where the channel contributes a surrogate lobe of CaM. Overall, this framework promises to set the table for future structural-biology and structure-function work.

More broadly, this regulatory scheme may explain paradoxes and open horizons. First, it has been asked how Ca2+/CaM could ever leave the IQ domain, when the binding affinity between these elements is so high4,5,29,39,53 (e.g., Ka/CaM–IQ = 5.88 × 10−4 Dfree−1 units in Fig. 3c). The answer may arise from the competing binding affinity for the tripartite complex (Fig. 8a, ICN), which multivalent ligand binding theory54 would approximate as Ka/CaM–PCI–IQ ~ Ka/CaM–PCI × Ka/PCI-IQ × (local concentration of IQ) = (4.35 × 10−5 Dfree units−1) × (3.45 × 10−5 Dfree units−1) × (1.36 × 108 Dfree units) ~ 0.2 Dfree units−1, a value far larger than Ka/CaM–IQ (Supplementary Note 23). Second, our scheme offers new interfaces targetable by native modulators and drug discovery. As L-type channel CDI influences cardiac arrhythmogenic potential15,18 and Ca2+ load in substantia nigral neurons prone to degeneration in Parkinson’s55, one could envisage a screen for selective modulators of N- or C-lobe CDI19. Third, our results offer a fine-grained roadmap for CaV1–2 splice/editing variants and channelopathies56. Indeed, we suspect that the design principles revealed here may generalize widely to other molecules modulated by CaM45,50,51,57.

METHODS

Molecular biology

To simplify mutagenesis, the wildtype construct in this study was an engineered CaV1.3 construct α1DΔ1626, nearly identical to and derived from the native rat brain variant (α1D, AF3070009). Briefly, the α1DΔ1626 construct, as contained with mammalian expression plasmid pCDNA6 (Invitrogen), features introduction of a silent and unique Kpn I site at a position corresponding to ~50 amino acid residues upstream of the carboxy terminal IQ domain (G1538T1539). As well, a unique Bgl II restriction site is present at a locus corresponding to ~450 amino acid residues upstream of the IQ domain. Finally, a unique Xba I and stop codon have been engineered to occur immediately after the IQ domain. These attributes accelerated construction of cDNAs encoding triple alanine mutations of α1DΔ1626. Point mutations of channel segments were made via QuikChange® mutagenesis (Agilent), prior to PCR amplification and insertion into the full-length α1DΔ1626 channel construct via restriction sites Bgl II/Kpn I, Kpn I/Xba I, or Bgl II/Xba I. Some triple alanine mutation constructs included a seven-aa extension (SRGPAVRR) after residue 1626. For FRET 2-hybrid constructs, fluorophore-tagged (all based on ECFP and EYFP) CaM constructs were made as described4. Other FRET constructs were made by replacing CaM with appropriate PCR amplified segments, via unique Not I and Xba I sites flanking CaM4. YFP-CaMC (Supplementary Fig. S4.1) was YFP fused to the C-lobe of CaM (residues 78–149). To aid cloning, the YFP-tagged CI region was made with a 12 residue extension (SRGPYSIVSPKC) via Not I / Xba I sites as above. This linker did not alter apoCaM binding affinity versus wild-type YFP-tagged CI region (not shown). Throughout, all segments subject to PCR or QuikChange® mutagenesis were verified in their entirety by sequencing.

Transfection of HEK293 cells

For whole-cell patch clamp experiments, HEK293 cells were cultured on 10-cm plates, and channels transiently transfected by a calcium phosphate method9. We applied 8 µg of cDNA encoding the desired channel α1 subunit, along with 8 µg of rat brain β2a (M80545) and 8 µg of rat brain α2δ (NM012919.2) subunits. We utilized the β2a auxiliary subunit to minimize voltage-dependent inactivation. For experiments involving CaM overexpression, we coexpressed 8 µg of rat CaMWT, CaM12, or CaM34, as described9. All of the above cDNA constructs were included within mammalian expression plasmids with a cytomegalovirus promoter. To boost expression, cDNA for simian virus 40 T antigen (1–2 µg) was co-transfected. For fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) 2-hybrid experiments, HEK293 cells were cultured on glass-bottom dishes and transfected with FuGENER 6 (Roche), before epifluorescence microscope imaging4. Electrophysiology/FRET experiments were performed at room temperature 1–3 days after transfection.

Whole-cell recording

Whole-cell recordings were obtained using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Electrodes were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, MTW 150-F4), yielding 1–3 MΩ resistances which were in turn compensated for series resistance by >70%. Currents were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz prior to digital acquisition at several times that frequency. A P/8 leak-subtraction protocol was used. The internal solution contained, (in mM): CsMeSO3, 114; CsCl2, 5; MgCl2, 1; MgATP, 4; HEPES (pH 7.4), 10; and BAPTA, 10; at 290 mOsm adjusted with glucose. The bath solution was (in mM): TEA-MeSO3, 102; HEPES (pH 7.4), 10; CaCl2 or BaCl2, 40; at 300 mOsm, adjusted with TEA-MeSO3.

FRET optical imaging

We conducted FRET 2-hybrid experiments in HEK293 cells cultured on glass-bottom dishes, using an inverted fluorescence microscope as extensively described by our laboratory4. Experiments utilized a bath Tyrode’s solution containing either 2 mM Ca2+ for experiments probing apoCaM binding or 10 mM Ca2+ with 4 µM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) for elevated Ca2+ experiments. 33-FRET efficiencies (EA) were computed as elaborated in our prior publications4. E-FRET efficiencies (ED), whose measurement methodology was developed and refined in other labortories41, could be determined from the same single-cell 33-FRET measurements using the following relationship, which expresses ED in terms of our own calibration metrics and standard measurements:

| (2) |

where G is a constant, defined as

| (3) |

SFRET, SYFP, and SCFP correspond to fluorescent measurements from the same cell using FRET, YFP, and CFP cubes whose spectral properties have been detailed previously4. RD1 and RA are constants relating to the respective spectral properties of ECFP and EYFP; ɛCFP(440 nm) / ɛYFP(440 nm) approximates the ratio of molar extinction coefficients of ECFP and EYFP at 440 nm, respectively; and MA/MD is the ratio of optical gain factors and quantum yields pertaining to EYFP and ECFP, respectively. Detailed descriptions of these parameters and their determination appear in our prior publications4. For all FRET efficiencies, spurious FRET relating to unbound ECFP and EYFP moities has been subtracted13. For 33-FRET, spurious FRET is linearly proportional to the concentration of CFP molecules, and the experimentally determined slopewas obtained from cells coexpressing ECFP and EYFP fluorophores. Similarly, for E-FRET, the spurious FRET is linearly proportional to the concentration of EYFP molecules. The slope for this relationship can be obtained from:

| (4) |

The methods for FRET 2-hybrid binding curves have been extensively described in previous publications3,4,41. Briefly, binding curves were determined by least-squared-error minimization of data from multiple cells, utilizing a 1:1 binding model with adjustment of parameters Kd,EFF and maximal FRET efficiency at saturating donor concentrations. For a small number of interactions involving mutations that strongly disrupted binding, the maximal FRET efficiency was set equal to that of the corresponding wild-type interaction and Kd,EFF varied to minimize errors. Standard-deviation error bounds on Kd,EFF estimates were determined by Jacobian error matrix analysis58.

Supplementary Note 24 characterizes our FRET 2-hybrid constructs, specifying their precise sequence composition, and behavior via western blot and confocal imaging analysis.

Molecular Modeling

De novo structural prediction was performed using the Robetta online server49 (http://robetta.bakerlab.org) as described in Supplementary Note 19,20–22. We used web-based molecular docking programs, PatchDock52 (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock/) and FireDock59 (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/FireDock/) to obtain preliminary models for molecular docking. Such preliminary models were subsequently used as starting models for further structural modeling and refinement using a customized docking protocol of PyRosetta60. A homology model of the C-lobe of apoCaM bound to IQ domain was constructed as described elsewhere42. All molecular models and atomic structures were visualized and rendered using PyMOL v1.2r1. (DeLano Scientific, LLC).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Paul Adams, Ivy Dick, and other members of the Ca2+ signals lab for valuable comments. Michael Tadross furnished early insights regarding the potential differences of mutation effects on C- and N-lobe forms of CDI. Ms. Wanjun Yang contributed substantial technical support, including western blots in Supplementary Figure S9. Manu Ben Johny, Philemon Yang, and Hojjat Bazzazi created mutant channels, performed electrophysiology and FRET experiments, and undertook extensive data analysis. Manu Ben Johny pioneered and conducted many of the FRET binding assays, performed molecular modeling, and undertook extensive software development. David Yue conceived and supervised the project; and helped formalize iTL theory and translation of 33-FRET to E-FRET methodologies. All authors refined hypotheses, wrote the paper, and created figures. Supported by grants from the NIMH (to D.T.Y.), NIDCD (P.S.Y. and Paul Fuchs), and NIMH (M.B.J.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunlap K. Calcium channels are models of self-control. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:379–383. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halling DB, Aracena-Parks P, Hamilton SL. Regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by calmodulin. Sci STKE. 2006;2006 doi: 10.1126/stke.3182006er1. er1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson MG, Alseikhan BA, Peterson BZ, Yue DT. Preassociation of calmodulin with voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels revealed by FRET in single living cells. Neuron. 2001;31:973–985. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erickson MG, Liang H, Mori MX, Yue DT. FRET two-hybrid mapping reveals function and location of L-type Ca2+ channel CaM preassociation. Neuron. 2003;39:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitt GS, et al. Molecular basis of calmodulin tethering and Ca2+-dependent inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30794–30802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhuri D, Issa JB, Yue DT. Elementary Mechanisms Producing Facilitation of Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) Channels. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:385–401. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMaria CD, Soong TW, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2001;411:484–489. doi: 10.1038/35078091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee A, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin binds to and modulates P/Q-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:155–159. doi: 10.1038/20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of L- type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuhlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:159–162. doi: 10.1038/20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang PS, et al. Switching of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CaV1.3 channels by calcium binding proteins of auditory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10677–10689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3236-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation and inactivation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6830–6838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06830.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dick IE, et al. A modular switch for spatial Ca2+ selectivity in the calmodulin regulation of CaV channels. Nature. 2008;451:830–834. doi: 10.1038/nature06529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tadross MR, Dick IE, Yue DT. Mechanism of local and global Ca2+ sensing by calmodulin in complex with a Ca2+ channel. Cell. 2008;133:1228–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alseikhan BA, DeMaria CD, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolmetsch R. Excitation-transcription coupling: signaling by ion channels to the nucleus. Sci STKE. 2003;2003 doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.166.pe4. PE4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans RM, Zamponi GW. Presynaptic Ca2+ channels--integration centers for neuronal signaling pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahajan A, et al. Modifying L-type calcium current kinetics: consequences for cardiac excitation and arrhythmia dynamics. Biophys J. 2008;94:411–423. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson ME, Mohler PJ. Rescuing a failing heart: think globally, treat locally. Nat Med. 2009;15:25–26. doi: 10.1038/nm0109-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Yang PS, Yang W, Yue DT. Enzyme-inhibitor-like tuning of Ca2+ channel connectivity with calmodulin. Nature. 2010;463:968–972. doi: 10.1038/nature08766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Findeisen F, et al. Calmodulin overexpression does not alter Cav1.2 function or oligomerization state. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:320–324. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.4.16821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori MX, Erickson MG, Yue DT. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science. 2004;304:432–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1093490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang PS, Mori MX, Antony EA, Tadross MR, Yue DT. A single calmodulin imparts distinct N- and C-lobe regulatory processes to individual CaV1.3 channels (abstr.) Biophys. J. 2007;92:354a. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhuri D, Alseikhan BA, Chang SY, Soong TW, Yue DT. Developmental activation of calmodulin-dependent facilitation of cerebellar P-type Ca2+ current. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:8282–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2253-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Ghosh S, Nunziato DA, Pitt GS. Identification of the components controlling inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2004;41:745–754. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee A, Zhou H, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent regulation of Ca(v)2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16059–16064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linse S, Helmersson A, Forsen S. Calcium binding to calmodulin and its globular domains. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8050–8054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuhlke RD, Pitt GS, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Ca2+-sensitive inactivation and facilitation of L-type Ca2+ channels both depend on specific amino acid residues in a consensus calmodulin-binding motif in the(alpha)1C subunit. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21121–21129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Petegem F, Chatelain FC, Minor DL., Jr Insights into voltage-gated calcium channel regulation from the structure of the CaV1.2 IQ domain-Ca2+/calmodulin complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fallon JL, Halling DB, Hamilton SL, Quiocho FA. Structure of calmodulin bound to the hydrophobic IQ domain of the cardiac Ca(v)1.2 calcium channel. Structure. 2005;13:1881–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mori MX, Vander Kooi CW, Leahy DJ, Yue DT. Crystal structure of the CaV2 IQ domain in complex with Ca2+/calmodulin: high-resolution mechanistic implications for channel regulation by Ca2+ . Structure. 2008;16:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim EY, et al. Structures of CaV2 Ca2+/CaM-IQ domain complexes reveal binding modes that underlie calcium-dependent inactivation and facilitation. Structure. 2008;16:1455–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Z, Vogel HJ. Structural basis for the regulation of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels: interactions between the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain and Ca2+-calmodulin. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:38. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chao SH, Suzuki Y, Zysk JR, Cheung WY. Activation of calmodulin by various metal cations as a function of ionic radius. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984;26:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanina T, Blumenstein Y, Shistik E, Barzilai R, Dascal N. Modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by Gβγ and calmodulin via interactions with N and C termini of α1C . J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:39846–39854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim EY, et al. Multiple C-terminal tail Ca2+/CaMs regulate CaV1.2 function but do not mediate channel dimerization. EMBO J. 2010;29:3924–3938. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fallon JL, et al. Crystal structure of dimeric cardiac L-type calcium channel regulatory domains bridged by Ca2+ calmodulins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5135–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807487106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pate P, et al. Determinants for calmodulin binding on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:39786–39792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asmara H, Minobe E, Saud ZA, Kameyama M. Interactions of calmodulin with the multiple binding sites of Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:397–404. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09342fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houdusse A, et al. Crystal structure of apo-calmodulin bound to the first two IQ motifs of myosin V reveals essential recognition features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19326–19331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H, Puhl HL, Koushik SV, 3rd, Vogel SS, Ikeda SR. Measurement of FRET efficiency and ratio of donor to acceptor concentration in living cells. Biophys J. 2006;91:L39–L41. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bazazzi HX, Ben Johny M, Yue DT. Continuously tunable Ca2+ regulation of RNA-edited CaV1.3 channels. in review. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Leon M, et al. Essential Ca(2+)-binding motif for Ca(2+)-sensitive inactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels. Science. 1995;270:1502–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chagot B, Chazin WJ. Solution NMR structure of Apo-calmodulin in complex with the IQ motif of human cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5. J Mol Biol. 2011;406:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feldkamp MD, Yu L, Shea MA. Structural and energetic determinants of apo calmodulin binding to the IQ motif of the Na(V)1.2 voltage-dependent sodium channel. Structure. 2011;19:733–747. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tadross MR, Ben Johny M, Yue DT. Molecular endpoints of Ca2+/calmodulin- and voltage-dependent inactivation of CaV1.3 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2010;135:197–215. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie C, Zhen XG, Yang J. Localization of the activation gate of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:205–212. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stotz SC, Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Functional roles of cytoplasmic loops and pore lining transmembrane helices int he voltage-dependent inactivation of HVA calcium channels. J Physiol. 2003;554:263–273. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim DE, Chivian D, Baker D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W526–W531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chagot B, Potet F, Balser JR, Chazin WJ. Solution NMR structure of the C-terminal EF-hand domain of human cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6436–6445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807747200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang C, Chung BC, Yan H, Lee SY, Pitt GS. Crystal Structure of the Ternary Complex of a NaV C-Terminal Domain, a Fibroblast Growth Factor Homologous Factor, and Calmodulin. Structure. 2012;20:1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black DJ, et al. Calmodulin interactions with IQ peptides from voltage-dependent calcium channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C669–C676. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00191.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jencks WP. On the attribution and additivity of binding energies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:4046–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan CS, et al. 'Rejuvenation' protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams PJ, Snutch TP. Calcium channelopathies: voltage-gated calcium channels. Subcell Biochem. 2007;45:215–251. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarhan MF, Van Petegem F, Ahern CA. A double tyrosine motif in the cardiac sodium channel domain III-IV linker couples calcium-dependent calmodulin binding to inactivation gating. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33265–33274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson KJ. Numerical methods in chemistry. Marcel Dekker; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mashiach E, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Andrusier N, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. FireDock: a web server for fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W229–W232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaudhury S, Lyskov S, Gray JJ. PyRosetta: a script-based interface for implementing molecular modeling algorithms using Rosetta. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:689–691. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.