The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet is perhaps the best example of how a nutrient dense dietary pattern can prevent chronic disease. In randomized trials, DASH dietary patterns lowered blood pressure in hypertensive individuals.1 Subsequent trials and observational studies have consistently found that DASH-type diets reduced cardiovascular and metabolic risk.2

Despite its proven health benefits, the DASH food pattern has not been widely adopted.3 Its limited uptake might be explained by economic constraints, since food prices influence food choices and constitute a major barrier to dietary change.4, 5 Nutrient-dense foods, central to DASH, tend to be more costly compared to calorie dense alternatives.6

In the present study we explored how diets consumed by US adults aligned with DASH guidance. We hypothesized that the DASH accordance of diets would be greater among persons of higher socioeconomic status. We also hypothesized that DASH-accordant diets would be more costly for some ethnic groups but not necessarily for others. Our previous analyses of US adults indicated that Hispanic adults achieved a diet quality similar to non-Hispanic white adults but at lower cost.7

Methods

Data for 4,744 adults from the 2001-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were used for analyses because they allow linkage of dietary data to a contemporaneous, national food price database. The data sources and linkage have been described in detail previously.7 Methods are provided in greater detail in the eAppendix.

The independent variable was a DASH accordance score similar to one previously applied to the Nurses’ Health Study.8 Our score was based on consumption of 5 encouraged food groups: fruits, vegetables (excluding fried potatoes and chips), nuts and legumes, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and three discouraged food and nutrient groups: red/processed meats, added sugars and sodium. Following an established approach, participants were scored on each of the food and nutrient groups and the sum of the scores (range of 8-40) represented the relative DASH accordance of each participant’s diet. Quintiles were used for analysis.

Age-adjusted descriptive analyses evaluated the DASH-score by socio-demographic strata. Survey-weighted linear regression models to examine diet cost and DASH adjusted for age group, sex, race/ethnicity, education and family income. An interaction between diet cost and DASH-score by race/ethnicity was also explored. Analyses accounted for the complex survey design of NHANES.

Results

Diets consumed by US adults had low DASH-accordance scores. The mean DASH score was 20.7, with a range of 8 to 38. DASH scores by demographic strata are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement. DASH accordance scores were highest among individuals with highest income and educational attainment. Non-Hispanic black adults had the lowest DASH accordance among the 3 predominant race/ethnicity groups.

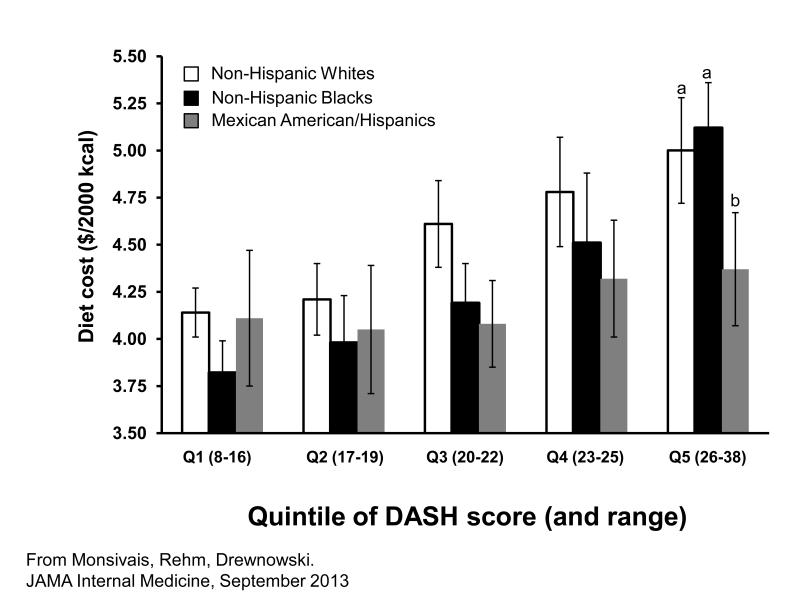

DASH accordance was positively associated with diet cost. In the supplement eTable 2 shows the energy-adjusted diet cost (dollars per 2000 kcal) by DASH-score quintile. Adults in the highest quintile (best accordance) consumed diets with a mean cost that was $0.78 higher (19%) than the cost of diets in the lowest quintile. Moreover, the association between DASH accordance and diet cost appeared to differ by race and ethnicity (P value for interaction = 0.04). Differences by race/ethnicity are evident in the Figure, which plots mean (95% confidence interval) of energy-adjusted diet cost by quintile of DASH score. For non-Hispanic black and white adults, there were significant differences in diet cost across quintiles of DASH accordance, with mean cost in the top quintile higher than the bottom quintile by $1.30 (34%) and $0.86 (21%) for black and white adults, respectively. By contrast, among Mexican-American and Hispanic (MAH) adults, mean diet cost in the top quintile was only $0.26 (6%) higher than the lowest quintile.

Figure.

Diet cost by quintile of DASH accordance score, stratified by race and ethnicity. Bars indicate mean and 95% confidence intervals for individual daily diet cost, adjusted for dietary energy and participant age and sex. $/2000 kcal indicates dollars per 2000 kcal.

a: P value for trend, <0.001 across quintiles.

b: P value for trend, nonsignificant.

Comment

According to NHANES data, diets consumed by US adults showed low DASH accordance scores, with the lowest scores occurring among disadvantaged groups. Overall, we also observed that diets with higher DASH accordance scores were more costly. Costs may explain why the DASH diet pattern has not been more widely adopted. While the DASH pattern was composed of readily available and palatable foods, food prices were not accounted for. Prices are one determinant of food choice5 and affordability of food was a factor of concern for African Americans considering adopting the DASH diet.4

It was therefore important to observe that for MAH adults, more DASH-accordant diets were not associated with significantly higher costs. While most observational studies indicate that nutritious diets are more costly,7 intervention and modeling studies have shown that improvements can be achieved in a cost-neutral fashion. Critical to achieving healthful diets affordably is the modification of the habitual diet to include foods that are both nutrient dense and relatively low-cost. Such foods may feature prominently in the diet patterns of MAH adults and contribute to the findings reported here. A detailed analysis was beyond the scope of the present study but our preliminary analyses (eTable 3 in the Supplement) indicate that MAH adults achieved both ‘encouraged’ and ‘discouraged’ components of DASH accordance at lower cost compared with other non-Hispanic adults.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the wider promotion of the DASH diet and other evidence-based dietary patterns is integral to population-level chronic disease prevention,9 but economic barriers may exist. While DASH-accordant diets were generally more costly, our results indicate that some ethnic eating patterns may hold a key to making healthful diets economically feasible for all Americans.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods and Results, and Supplementary Tables 1-3

Funding Acknowledgement

Supported by NIH grant 1R21DK085406 to AD. PM was also supported by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) Public Health Research Centre of Excellence with funding from the British Heart Foundation, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research and the Wellcome Trust under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration.

References

- 1.Karanja N, Erlinger TP, Pao-Hwa L, Miller ER, 3rd, Bray GA. The DASH diet for high blood pressure: from clinical trial to dinner table. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004 Sep;71(9):745–753. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.9.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L. Components of a cardioprotective diet: new insights. Circulation. Jun 21;123(24):2870–2891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mellen PB, Gao SK, Vitolins MZ, Goff DC., Jr. Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Feb 11;168(3):308–314. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertoni AG, Foy CG, Hunter JC, Quandt SA, Vitolins MZ, Whitt-Glover MC. A multilevel assessment of barriers to adoption of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) among African Americans of low socioeconomic status. J Health Care Poor Underserved. Nov;22(4):1205–1220. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steenhuis IH, Waterlander WE, de Mul A. Consumer food choices: the role of price and pricing strategies. Public Health Nutr. Dec;14(12):2220–2226. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Nov;92:1181–1188. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehm CD, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A. The quality and monetary value of diets consumed by adults in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Sep 14; doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.015560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Apr 14;168(7):713–720. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL, et al. Population approaches to improve diet, physical activity, and smoking habits: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. Sep 18;126(12):1514–1563. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318260a20b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods and Results, and Supplementary Tables 1-3