Abstract

Long-term patient adherence to osteoporosis treatment is poor despite proven efficacy. In this study, we aimed to assess the impact of active patient training on treatment compliance and persistence in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In the present national, multicenter, randomized controlled study, postmenopausal osteoporosis patients (45-75 years) who were on weekly bisphosphonate treatment were randomized to active training (AT) and passive training (PT) groups and followed-up by 4 visits after the initial visit at 3 months interval during 12 months of the treatment. Both groups received a bisphosphonate usage guide and osteoporosis training booklets. Additionally, AT group received four phone calls (at 2nd, 5th, 8th, and 11th months) and participated to four interactive social/training meetings held in groups of 10 patients (at 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 12th months). The primary evaluation criteria were self-reported persistence and compliance to the treatment and the secondary evaluation criteria was quality life of the patients assessed by 41-item Quality of Life European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO-41) questionnaire.. Of 448 patients (mean age 62.4±7.7 years), 226 were randomized to AT group and 222 were randomized to PT group. Among the study visits, the most common reason for not receiving treatment regularly was forgetfulness (54.9% for visit 2, 44.3% for visit 3, 51.6% for visit 4, and 43.8% for visit 5), the majority of the patients always used their drugs regularly on recommended days and dosages (63.8% for visit 2, 60.9% for visit 3, 72.1% for visit 4, and 70.8% for visit 5), and most of the patients were highly satisfied with the treatment (63.4% for visit 2, 68.9% for visit 3, 72.4% for visit 4, and 65.2% for visit 5) and wanted to continue to the treatment (96.5% for visit 2, 96.5% for visit 3, 96.9% for visit 4, and 94.4% for visit 5). QUALEFFO scores of the patients in visit 1 significantly improved in visit 5 (37.7±25.4 vs. 34.0±14.6, p<0.001); however, the difference was not significant between AT and PT groups both in visit 1 and visit 5. In conclusion, in addition to active training, passive training provided at the 1st visit did not improve the persistence and compliance of the patients for bisphosphonate treatment.

Keywords: Bisphosphonates, osteoporosis, patient education, medication adherence.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a highly prevalent disease characterized by low bone mass and decreased bone quality leading to bone fragility and increased risk of fractures1. Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a bone mineral density of 2.5 standard deviations or more below the mean peak bone mass (average of young, healthy adults) as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.2 About 30% of postmenopausal women in the United States and Europe are estimated to have osteoporosis3. A recent report revealed that osteoporosis and hip fracture were prevalent in Turkey as well. The lifetime probability of sustaining a hip fracture at the age of 50 years was 15% in women.4

Osteoporosis is mostly an asymptomatic disease until an individual experiences a fracture. In particular, osteoporotic hip or vertebral fractures, increase morbidity and mortality, affect quality of life of the individual and pose an economic burden on the community.5-7 Clinical trials have shown that osteoporosis treatment by oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate and risedronate is quite effective, increasing bone mass and preventing vertebral fractures8-11.

As with all chronic diseases osteoporosis treatment success relies on patient adherence. Two aspects of patient adherence, compliance (receiving treatment as per the instructions of the physician at regular intervals and dosages) and persistence of treatment (continuing to receive treatment over the long-term) are key factors in treatment success. However, osteoporosis treatments are often hampered by low adherence of the patients due to a number of reasons including poor communication between patient and physician, lack of motivation and non belief in fracture risk, among others. A review of results from 14 large databases concluded that adherence to bisphosphonate treatment is suboptimal with one-year persistence rates ranging from 17.9% to 78%, and compliance assessed by medication possession ratio ranging from 0.59 to 0.8112. Interventions to increase patients' knowledge, involve patients in medical decision making, and motivate patients to continue treatment may help improve adherence to osteoporosis medications13-15.

In this national, multicenter randomized controlled study, we aimed to assess the impact of active training on treatment compliance and persistence in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis receiving weekly bisphosphonate treatment over the course of 12 months.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient population

The present study was planned as a national, multi-center, randomized controlled study in Turkey. Women who aged between 45 and 75 years, had a diagnosis of postmenopausal osteoporosis according to WHO criteria, and had a clinical presentation appropriate for osteoporosis treatment with weekly oral bisphosphonates (alendronate 70 mg, risedronate 35 mg) based on the investigator's clinical judgment were included. However, women who had a secondary osteoporosis and were under osteoporosis treatment such as SERM, HRT, calcitonin, strontium ranelate, and any bisphosphonates were excluded.

Due to non-interventional nature of the study, the treatment and follow-up procedures were left to the discretion of the physician, considering the fact that bisphosphonates are the first line choice in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Turkey. The investigators were only asked to collect the study data in accordance with the principles of Good Epidemiological Practice.

The study was approved by both the Local Ethics Committee of Marmara University Faculty of Medicine and the Ethics Committee of Ministry of Health before initiation of the study and the signed informed consent was obtained from all patients. Verbal consent was also obtained for illiterate patients. Additionally, it was asked some help from their relatives for patients' training and study procedures.

Patients were randomized into two groups as active training (AT) group and passive training (PT) group. Randomization was performed centrally by means of 20-patient block design. Stratification was performed according to predefined patient characteristics.

Patients' training and study procedures

Patients were followed-up by 4 visits after the initial visit at 3 months interval during 12 months of the treatment.. Patients in both groups were given a “Starter Training Kit” including bisphosphonate usage guide and osteoporosis training booklets (e.g. Osteoporosis in General, Osteoporosis and Exercise, Osteoporosis and Nutrition, Osteoporosis and Patient Rights). The AT group was additionally trained through a standard training package including four telephone calls (on 2nd, 5th, 8th, and 11th months of treatment) and four interactive /educational meetings (on 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 12th months of treatment) held in groups of ten patients. During the telephone calls, patients were reminded to read the booklets, informed of the topic to be covered in the next educational meeting and invited to the meeting. The topics of the four educational meetings were: Osteoporosis in General, Osteoporosis and Exercise, Osteoporosis and Nutrition, Osteoporosis and Patient Rights. A certificate was given to the patients who attended all four of the educational meetings.

An “Osteoporosis Awareness Test” was given twice to all of study patients during the first (0-1st month of treatment) and fifth (12th month of treatment) study visits.

Adverse events, spontaneously reported by the patient and/or noted by the investigator, were recorded throughout the study.

Evaluation criteria

The primary evaluation criteria were treatment compliance and persistency based on the information given to the investigator by the patient. The secondary evaluation criteria were vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, adverse events, and quality of life. Quality of life of the patients was evaluated by 41-item Quality of Life European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO-41) questionnaire. The QUALEFFO-41 is a quality-of-life questionnaire especially developed for measuring quality of life in patients with vertebral deformities16. It consists of 41 questions arranged in five domains: pain, physical function, social function, general health perception, and mental function. The Turkish version of QUALEFFO was reported to be reliable and valid in the evaluation of patients with osteoporosis17.

Statistical analysis

Data of the study were analyzed using STATA-10 Software. All statistical analyses were performed at the 5% significance level using 2-sided tests. The quantitative variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum. The qualitative variables were expressed as the number of non-missing data, counts, and percentages. Any missing data or unknown responses were counted in the percentages. For comparison of continuous variables, student-t test and ANOVA were used for parametric variables) and Mann Whitney-U and Kruskal Wallis tests were used for non-parametric variables. For comparison of paired variables, Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. For comparison of all categorical data Chi Square and Fisher Exact test was performed. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

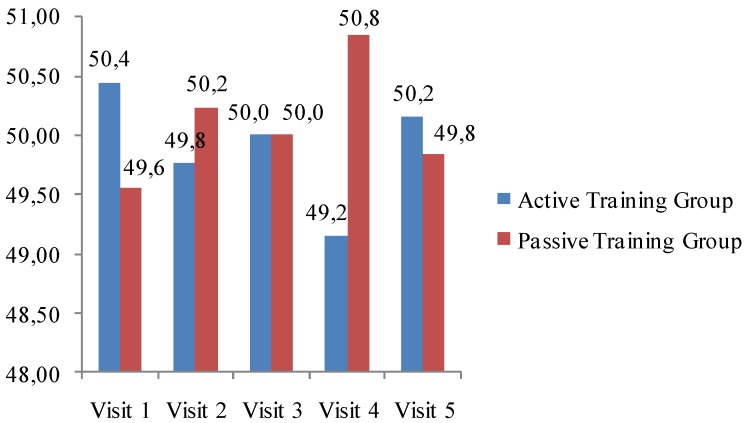

A total of 448 female patients (mean age 62.4±7.7 years) treated with weekly bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate) for postmenopausal osteoporosis were included in the study. Of these patients, 226 (50.5%) were randomized to the AT group and 222 (49.5%) to the PT group; 305 patients (155 from AT group and 150 from PT group) completed the study. There was no statistically significant difference between AT and PT groups in study visit attendance (p>0.05). The actual attendance of the groups to the study visits is demonstrated in Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Actual attendance of the groups to the study visits.

Among 448 study patients, 238 (53.1%) were graduated from elementary school and 92 (20.5%) were illiterate. Of the patients, 274 (61.7%) had any concomitant chronic diseases, 198 (44.6%) had hypertension, 98 (22.1%) had hyperlipidemia, and 45 (10.1%) had diabetes mellitus (Table 1). The baseline T scores are also presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic demographic and clinical data of the patients.

| Demographic and clinical features | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SD | 62.4±7.7 years | |

| Education Level, n (%) | Illiterate | 92 (20.5) |

| Elementary | 238 (53.1) | |

| High school | 67 (15.0) | |

| University/post-graduate | 51 (11.4) | |

| Concomitant chronic diseases, n (%) | Any chronic disease | 274 (61.7) |

| Hypertension | 198 (44.6) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 98 (22.1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 45 (10.1) | |

| Thyroid diseases | 36 (8.1) | |

| Heart failure | 39 (8.8) | |

| Others | 96 (21.4) | |

| Baseline T scores, mean±SD | Neck (n=403) | -2.17±0.92 |

| Trochanter (n=325) | -1.71±0.97 | |

| Total (n=351) | -1.74±1.04 | |

| L1-L4 (n=407) | -2.63±0.8 | |

SD, Standard Deviation.

Osteoporosis Awareness Questionnaire

In total, 444 patients at visit 1 and 299 patients at visit 2 answered the Osteoporosis Awareness Questionnaire. According to the questionnaire, the major reason for applying to an osteoporosis clinic was pain, which was detected in 254 patients (57.2%). Nearly half of the patients (n=219, 49.3%) mentioned that they received information on osteoporosis from Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Specialists.

The Osteoporosis Awareness Questionnaire questions on the definition, reasons for, outcomes, treatments and risk assessment, were answered correctly by 29-48% of patients at visit 1 and by 39-50% at visit 5. This increase was statistically significant for the definition and treatment of osteoporosis in both AT and PT groups, and for reasons for osteoporosis in AT group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of Osteoporosis Awareness Questionnaire of the study groups according to the visits.

| Question for osteoporosis | Correct answer | AT group n (%) |

PT group n (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 5 | p value | Visit 1 | Visit 5 | p value | ||

| Definition | Osteoporosis is a bone disease | 148 (33.3) | 132 (44.1) | 0.002 | 138 (31.1) | 131 (49.8) | 0.004 |

| Reason | The reasons of osteoporosis are genetics, hormonal deficiency, nutritional deficiency, lack of exercise | 133 (30.0) | 122 (40.8) | 0.002 | 129 (29.0) | 102 (34.1) | 0.15 |

| Outcome | The results of osteoporosis are kyphosis, fractures, pain, loss of height | 168 (37.8) | 123 (41.1) | 0.41 | 150 (33.8) | 116 (38.8) | 0.16 |

| Treatment | Osteoporosis is a treatable disease | 172 (38.7) | 139 (46.6) | 0.03 | 162 (36.5) | 135 (45.3) | 0.01 |

| Risk assessment | The risk of osteoporosis is determined by consulting a physician | 215 (48.4) | 150 (50.2) | 0.59 | 206 (46.4) | 149 (49.8) | 0.28 |

AT, Active Training; PT, Passive Training.

Treatment compliance and persistence

During visit 1, 238 (53.2%) patients, 125 in AT group and 113 in PT group, were receiving alendronate; while 209 (46.8%) patients, 101 in AT group and 108 in PT group, were receiving risedronate. There were no significant differences between AT and PT groups among the visits regarding the rates of patients who received bisphosphonate treatment, who received bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day, who did not receive bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day, and who did not complete the specified bisphosphonate dosage (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment compliance and persistency of the patients in the study groups.

| AT group n (%) |

PT group n (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment | |||

| Visit 2 | 210 (49.8) | 212 (50.2) | 0.922 |

| Visit 3 | 191 (50.8) | 185 (49.2) | 0.759 |

| Visit 4 | 175 (49.1) | 178 (50.9) | 0.747 |

| Visit 5 | 152 (50.5) | 149 (49.5) | 0.862 |

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | |||

| Visit 2 | 122 (53.7) | 105 (46.3) | 0.261 |

| Visit 3 | 115 (56.6) | 83 (43.4) | 0.068 |

| Visit 4 | 110 (51.2) | 105 (48.8) | 0.734 |

| Visit 5 | 104 (51.7) | 97 (48.3) | 0.622 |

| Patients who did not receive bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | |||

| Visit 2 | 88 (45.1) | 107 (54.9) | 0.176 |

| Visit 3 | 76 (42.7) | 102 (57.3) | 0.054 |

| Visit 4 | 60 (45.8) | 71 (54.8) | 0.305 |

| Visit 5 | 50 (48.5) | 53 (51.5) | 0.766 |

| Patients who did not complete bisphosphonate dose | |||

| Visit 2 | 31 (50.0) | 31 (50.0) | 1.000 |

| Visit 3 | 31 (47.7) | 34 (52.3) | 0.710 |

| Visit 4 | 22 (53.7) | 19 (46.3) | 0.640 |

| Visit 5 | 14 (43.8) | 18 (56.2) | 0.484 |

AT, Active Training; PT, Passive Training.

There were no significant differences in terms of treatment compliance between the state and university hospital settings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Treatment compliance and persistency of the patients in the study groups according to their follow-ups in university and state hospitals.

| University hospital n (%) |

State hospital n (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT group | PT group | p value | AT group | PT group | p value | ||

| Visit 2 | |||||||

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment | 106 (49.1) | 110 (50.9) | - | 104 (50.5) | 102 (49.5) | - | |

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 64 (57.1) | 48 (42.9) | 0.036 | 58 (50.9) | 56 (49.1) | 0.790 | |

| Patients who did not receive bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 42 (40.4) | 62 (59.6) | 0.005 | 46 (50.0) | 46 (50.0) | - | |

| Patients who did not complete bisphosphonate dose | 41 (40.6) | 60 (59.4) | 0.007 | 43 (50.0) | 43 (50.0) | - | |

| Visit 3 | |||||||

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment | 103 (49.0) | 107 (51.0) | - | 88 (53.0) | 78 (47.0) | - | |

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 64 (64.6) | 35 (65.4) | - | 51 (51.5) | 48 (48.5) | - | |

| Patients who did not receive bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 39 (35.1) | 72 (34.9) | - | 37 (55.2) | 30 (44.8) | - | |

| Patients who did not complete bisphosphonate dose | 39 (35.8) | 70 (64.2) | 0.01 | 35 (54.7) | 29 (45.7) | 0.289 | |

| Visit 4 | |||||||

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment | 101 (49.5) | 103 (50.5) | - | 75 (51.0) | 72 (49) | - | |

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 58 (59.6) | 59 (50.4) | - | 53 (53.5) | 46 (46.5) | - | |

| Patients who did not receive bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 43 (49.4) | 44 (50.6) | - | 19 (39.6) | 29 (60.4) | - | |

| Patients who did not complete bisphosphonate dose | 41 (49.4) | 42 (50.6) | - | 16 (36.4) | 28 (63.6) | - | |

| Visit 5 | |||||||

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment | 94 (50.8) | 91 (49.2) | - | 61 (50.8) | 59 (49.2) | - | |

| Patients who received bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 49 (46.7) | 56 (53.3) | 0.345 | 55 (57.3) | 41 (42.7) | 0.043 | |

| Patients who did not receive bisphosphonate treatment at the exact day | 45 (59.2) | 31 (40.8) | 0.023 | 5 (25.0) | 15 (75.0) | 0.002 | |

| Patients who did not complete bisphosphonate dose | 38 (55.1) | 31 (44.9) | 0.224 | 16 (76.2) | 5 (23.8) | 0.001 | |

AT, Active Training; PT, Passive Training.

The most common reason for not receiving treatment regularly was forgetfulness among the study visits (54.9% for visit 2, 44.3% for visit 3, 51.6% for visit 4, and 43.8% for visit 5). The majority of the patients always used their drugs regularly on recommended days and dosages (63.8% for visit 2, 60.9% for visit 3, 72.1% for visit 4, and 70.8% for visit 5). Most of the study patients were highly satisfied with the treatment (63.4% for visit 2, 68.9% for visit 3, 72.4% for visit 4, and 65.2% for visit 5) and wanted to continue to the treatment (96.5% for visit 2, 96.5% for visit 3, 96.9% for visit 4, and 94.4% for visit 5) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Reasons for not receiving treatment regularly and treatment satisfaction of the patients during the study visits.

| Visit 2 (n=423) |

Visit 3 (n=376) |

Visit 4 (n=351) |

Visit 5 (n=355) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did the patient use the drug as recommended? | Always | 73.0 | 72.6 | 79.2 | 77.0 |

| Mostly | 25.3 | 24.7 | 19.4 | 21.6 | |

| Rarely | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | |

| What is the reason for the missing dose? | Forgetfulness | 54.9 | 44.3 | 51.6 | 43.8 |

| Economical reasons | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 4.1 | |

| Traveling /Holidays | 9.3 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 4.1 | |

| Other | 32.3 | 44.3 | 36.9 | 47.9 | |

| Does the patient think that it is difficult to continue the treatment as recommended? | Yes | 4.5 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 5.9 |

| Slightly | 18.9 | 13.8 | 15.1 | 18.4 | |

| No | 76.6 | 82.7 | 81.5 | 75.7 | |

| Did the patient use the drug regularly on recommended days and dosages? | Always | 63.8 | 60.9 | 72.1 | 70.8 |

| Mostly | 34.3 | 36.7 | 26.2 | 27.2 | |

| Rarely | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.0 | |

| What do you think about the efficacy of bisphosphonate treatment you used? | Very good | 13.2 | 12.8 | 15.1 | 18.0 |

| Good | 65.2 | 73.9 | 75.2 | 70.2 | |

| Moderate | 19.4 | 10.9 | 9.1 | 10.8 | |

| Poor | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | |

| What do you think about the safety/tolerability of bisphosphonate treatment you used? | Very good | 18.2 | 16.8 | 19.1 | 20.7 |

| Good | 61.0 | 71.3 | 69.7 | 67.2 | |

| Moderate | 18.7 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 11.5 | |

| Poor | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| Treatment toleration | Very good | 25.8 | 21.8 | 19.1 | 19.7 |

| Good | 61.9 | 68.4 | 75.5 | 73.8 | |

| Moderate | 9.7 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 5.9 | |

| Poor | 2.6 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | |

| Patient's satisfaction with the treatment | Very high | 20.1 | 17.0 | 15.7 | 21.3 |

| High | 63.4 | 68.9 | 72.4 | 65.2 | |

| Medium | 14.0 | 11.7 | 10.5 | 12.8 | |

| Low | 2.6 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 | |

| How does the patient feel after the last visit? | Same | 50.4 | 49.2 | 59.3 | 47.2 |

| Better | 44.0 | 43.1 | 36.5 | 47.5 | |

| Worse | 5.7 | 7.7 | 4.3 | 5.3 | |

| Does the patient want to continue the treatment? (Persistence) |

Yes | 96.5 | 96.5 | 96.9 | 94.4 |

| No | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 5.6 | |

Data are presented as percentages.

Quality of Life Assessment

There was a significant difference between the QUALEFFO scores of all patients in visit 1 and visit 5 (37.7±25.4 vs. 34.0±14.6, p<0.001); however, no significant difference was found between the QUALEFFO scores of the AT and PT groups both in visit 1 and visit 5 (Table 6).

Table 6.

QUALEFFO scores of the study groups.

| AT group | PT group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | 37.5±15.0 | 37.9±15.9 | 0.956 |

| Visit 5 | 32.9±14.7 | 35.1±14.4 | 0.165 |

AT, Active Training; PT, Passive Training.

Safety

During the study, 10 fractures (6 in AT group and 4 in PT group) and 6 adverse events (4 in AT group and 2 in PT group) of which one of them was serious were reported. No significant difference was observed between the study groups in terms of either vertebral or non-vertebral fractures.

Discussion

This national multicenter observational study on postmenopausal osteoporotic women found no difference between active training and passive training in terms of persistence and compliance to weekly bisphosphonate treatments. The osteoporosis awareness test conducted at baseline and at 12 months consisted of basic questions on osteoporosis and a similar improvement in knowledge was detected in both groups.

In patient surveys the main reason for missing a dose was stated as forgetfulness. Most patients persistent through 12 months of treatment thought that the medication was effective, safe and well tolerated and their overall treatment satisfaction was high or very high. Furthermore, a majority of persistent patients showed an interest in continuing the weekly bisphosphonate treatment. QUALEFFO scores improved similarly in both groups, emphasizing that treatment was perceived as beneficial by patients persistent with their treatment at 12 months. However, QUALEFFO may be due to the fact that 57% of the patients presented with pain and pain due to fracture tend to diminish over time even in the absence of treatment.

A variety of interventions were tested in randomized trials as possible ways of improving adherence to osteoporosis treatment. In a study based in Denmark, patient education by a multidisciplinary team in small groups over 4 weeks significantly improved adherence to osteoporosis therapy, compared to no education group18. However, adherence rate was reported to be exceedingly higher than average for both groups: 92% for school group and 80% for control group, two years after initiation of therapy18. Thus far, this Danish study is the only example of patient education improving long-term adherence in osteoporosis treatment. Educational interventions were successful in increasing treatment adherence for other chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease19, but there is more incentive to adhere to treatment in these diseases as the patient has symptoms. Factors such as education level, socioeconomic status or cultural differences may also contribute to patients' receptiveness of health-related information/training provided by health care professionals19. In the present study, trainings had no impact on treatment compliance and persistence as there were no significant differences between the AT and PT groups regarding the receiving or not receiving treatment at the exact day and not completing the treatment dosage.

Another education-related intervention involved face-to-face training of primary care physicians by trained pharmacists, while automated phone calls and letters were used to inform their patients20. Although this approach increased the number of patients starting on osteoporosis medication, adherence was not significantly different than the control group (PCPs and patients not receiving education) after 10 months of follow-up19. Similarly, handing out an educational leaflet about osteoporosis at the start of treatment versus regular practice did not improve adherence to therapy21.

Since osteoporosis is an asymptomatic disease and bone mass densitometry is generally repeated only 2 years after initiation of treatment, patients do not get immediate feedback. A randomized study investigated the impact of physician reinforcement using bone turnover markers (BTM) on persistence with risedronate treatment22. Although both patients receiving and not receiving reinforcement had high persistence rates, patients with good BTM response had significantly increased persistence. However, patients with similar and poor BTM responses had similar and worse persistence as compared to patients receiving no reinforcement.22 However, good responses in biochemical markers could be the result of better persistence rather than its cause.

In another study, Clowes et al. showed improved adherence with raloxifene use when a nurse monitoring system was implemented23. However, in the same study sharing BTM response information with the patient did not improve adherence beyond nurse-monitoring23. Clowes at al. described nurse monitoring as attention to patient by a health care professional at 3-monthly visits by means of questions related to patient well-being, medication problems and adverse events. In that sense our study has also implemented a form of monitoring to both active and passive training groups, and this may have influenced the adherence rates, perhaps even masking the effect of education on adherence.

Bisphosphonate usage presents certain inconveniences since it has to be taken with a full glass of water after an overnight fast, no food or drink should be consumed and the patient should remain upright for the following half hour. Thus, one way of improving adherence may be to decrease dose frequency. In a UK study comparing weekly and monthly bisphosphonate preparations, adherence was significantly improved in patients allocated to monthly ibandronate plus a patient support program where phone calls reminded patients of their upcoming dose and stressed the importance of adherence to therapy24. Such reminders become important in less frequent dosing options as it is easier to forget about the medication altogether. Availability of quarterly or yearly intravenous bisphosphonate formulations may also improve adherence in selected patient populations25.

The present study had some limitations. Due to the observational nature of the study no strict monitoring devices were used to determine the compliance of the patient. Instead we relied on voluntary patient information to determine if the medications were taken on a timely manner, at recommended dosages, per physicians' instructions. Some patients may feel embarrassed to admit that they missed some doses or did not follow instructions. In addition, follow-up visits every 3 months is unlikely to reflect real-life practices and may have influenced patients to be more adherent to treatment during the study period.

In conclusion, an active training program consisting of small group meetings every 3 months and reminder phone calls did not improve persistence and compliance for bisphosphonate treatment.

Acknowledgments

Sanofi-aventis Turkey provided funding for the study. We would like to thank following researchers for their contribution to the study: (Alphabetical order) Ü. Akarırmak, E. Akcan, S. Akı, A. Alp, S. Bal, S. Başaran, S. Büyükkaya, A. Çevikol, E. Esen, A. Gürgan, P. Işıkçı, K. Kaya, T. Kaya, N. Ölmez, M. Sarıdoğan, EK Saygı, F. Şahin, C. Tezel, FG Uysal; and to Cagla Isman, MD and Prof. Sule Oktay, MD, PhD. from KAPPA Consultancy Traning Research Ltd, Istanbul who provided editorial support funded by sanofi-aventis Turkey.

References

- 1.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organization technical report series. 1994;843:1–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock O, Felsenberg D. Bisphosphonates in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis--optimizing efficacy in clinical practice. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:279–97. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuzun S, Eskiyurt N, Akarirmak U. et al. Incidence of hip fracture and prevalence of osteoporosis in Turkey: the FRACTURK study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:949–55. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Ensrud KC. et al. Risk of mortality following clinical fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:556–61. doi: 10.1007/s001980070075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D. et al. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999;353:878–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726–33. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB. et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE. et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK. et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH. et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s001980050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1023–31. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleeson T, Iversen MD, Avorn J. et al. Interventions to improve adherence and persistence with osteoporosis medications: a systematic literature review. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:2127–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold DT, Alexander IM, Ettinger MP. How can osteoporosis patients benefit more from their therapy? Adherence issues with bisphosphonate therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1143–50. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverman SL, Schousboe JT, Gold DT. Oral bisphosphonate compliance and persistence: a matter of choice? Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:21–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lips P, Cooper C, Agnusdei D. et al. Quality of life in patients with vertebral fractures: validation of the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO). Working Party for Quality of Life of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10:150–60. doi: 10.1007/s001980050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocyigit H, Gulseren S, Erol A. et al. The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO) Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:18–23. doi: 10.1007/s10067-002-0653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen D, Ryg J, Nielsen W. et al. Patient education in groups increases knowledge of osteoporosis and adherence to treatment: a two-year randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansà M, Hernández C, Vidal M. et al. Multidimensional analysis of treatment adherence in patients with multiple chronic conditions. A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu AD, Stedman MR, Polinski JM. et al. Adherence to osteoporosis medications after patient and physician brief education: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:417–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guilera M, Fuentes M, Grifols M. et al. Does an educational leaflet improve self-reported adherence to therapy in osteoporosis? The OPTIMA study. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:664–71. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delmas PD, Vrijens B, Eastell R. et al. Improving Measurements of Persistence on Actonel Treatment (IMPACT) Investigators. Effect of monitoring bone turnover markers on persistence with risedronate treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1296–304. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R. The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1117–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper A, Drake J, Brankin E. Treatment persistence with once-monthly ibandronate and patient support vs. once-weekly alendronate: results from the PERSIST study. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warriner AH, Curtis JR. Adherence to osteoporosis treatments: room for improvement. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:356–62. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832c6aa4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]