Abstract

Anxiety disorders are common after stroke. However, information on how to treat them with psychotherapy in this population is highly limited. Modified cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) has the potential to assist. Two cases of individuals treated with modified CBT for anxiety after stroke are presented. The modification was required in light of deficits in executive and memory function in one individual and in the context of communication difficulties in the other. The anxiety symptoms were treated over seven and nine sessions, respectively. Both participants improved following the intervention, and these improvements were maintained at 3 month follow-ups. Further case-series and randomised controlled designs are required to support and develop modified CBT for those with anxiety after stroke.

Keywords: Stroke, Anxiety, Cognitive-behaviour therapy, Single case design

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the biggest cause of disability in the developed world. The difficulties resulting from it include cognitive (e.g., memory, concentration) deficits and language disorders (Lincoln, Kneebone, Macniven, & Morris, 2012). Up to 70% of people with stroke encounter cognitive dysfunction (Lesniak, Bak, Czepiel, Seniow, & Czlonkowska, 2008; Nys et al., 2007) and around 12% of stroke survivors are left with significant aphasia at six months (Wade, Langton Hewer, David, & Enderby, 1986). Given the effect stroke can have on an individual it is not surprising that anxiety is common, occurring with or separate to depression. A pooled (across time) estimate of the rate of anxiety after stroke is between 18 and 25% (Campbell Burton et al., 2012). In addition to being distressing itself, this anxiety may affect daily functioning, quality of life, relationships and functional outcome (Aström, 1996; Carod-Artal & Egido, 2009; Ferro, Caeiro, & Santos, 2009; West, Hill, Hewison, Knapp, & House, 2010).

A recent systematic review (Campbell Burton et al., 2011) found no studies meeting inclusion criteria that considered psychological treatment of anxiety in the context of stroke. Indeed, even medication studies were restricted to those investigating treatment of anxiety with co-occurring depression. The authors concluded that while there is some evidence to support the use of medications in these circumstances, undesirable side effects are common. Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural psychotherapies are proven in the treatment of anxiety in the general population (e.g., Ayers, Sorrell, Thorp, & Wetherell, 2007). One of the difficulties in psychological treatment of anxiety (and in researching treatment) of those with stroke can be cognitive and communication problems, that impact on the ability of standard treatments to be given. Modified treatment is supported by research indicating that unmodified CBT is not successful in treating depression after stroke (Lincoln & Flannaghan, 2003), but behavioural treatments that consider deficits have proved efficacious (Thomas, Walker, Macniven, Haworth, & Lincoln, 2013). While a number of authors have urged that modified CBT be provided that includes attention to cognitive deficits, including via cognitive rehabilitation (Broomfield et al., 2010; Hibbard, Grober, Gordon, & Aletta, 1990; Lincoln et al., 2012) they have been concerned only with depression and case descriptions are limited. Some support that modified CBT would be useful for those with anxiety after stroke comes from group controlled studies of those with acquired brain injury (ABI), including some participants with stroke (Waldron, Casserly, & O'Sullivan, 2012). CBT targeting depression and anxiety in those with ABI has been found to significantly reduce anxiety (Arundine et al., 2012; Bradbury et al., 2008) and a modified CBT intervention to reduce social anxiety in those with ABI, while not successful in reducing its target concern, did appear to reduce general anxiety (Hodgson, McDonald, Tate, & Gertler, 2005). The intention of the current paper was to address the lack of evidence for CBT treatment of anxiety after stroke by describing the treatment of anxiety without significant co-morbid depression, in two people after stroke, using modified treatment that considers cognitive and communication deficits. It was expected, given the efficacy of behavioural and cognitive-behavioural treatments in treating anxiety in people without stroke, and support from the ABI literature treating individuals with these procedures, making provision for their disabilities, would lead to reductions in anxiety.

PARTICIPANT 1

Method

Participant

Ned (not his real name) was a 62-year-old company director. He encountered a stroke as a consequence of a right total carotid artery occlusion against a background of type II diabetes. The MRI scan identified right temporal and thalamic infarcts and punctuate infarcts of the frontal and parietal lobes. Initial evaluations noted dysarthria, left facial weakness and dyspraxia. Ned was in the acute hospital for 18 days then transferred to a post-acute unit where he underwent rehabilitation for 8 days. At his discharge he was described as having “minimal residual deficits”. Planning and problem solving deficits, however, were identified on the Cognitive Assessment of Minnesota (CAM), by a stroke team for early discharge after he had left inpatient care.

Ned was referred to the psychologist on account of anxiety 7 months after his stroke. By this time he had been experiencing anxiety since just after his discharge from hospital, that is for approximately 6 months. This was despite having made a good physical recovery; he was playing squash again and his golf was objectively at 80% of his pre-stroke level. Ned had found himself waking up “full of fear” with a lump in his chest. At these times he felt like he was trembling, although he was not physically doing so. He noticed anxiety particularly at work. For instance he described his stream of thoughts when he encountered problems trying to download an attachment from a file on a computer, “I can't do it,” “I have let her [his wife] down,” “I won't understand it,” “I won't know what to do”. Interview also established Ned experienced excessive worry about his future financial security. Ned's anxiety was confirmed by a score of 12 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety sub-scale, as noted in his referral letter. His score on the Depression sub-scale of this measure was in the non-clinical range. Ned's goals for therapy were to: “Not wake with a knot in his chest” and “Be more relaxed and perform better at work.”

Formulation

On the basis of the initial interview with Ned, it was confirmed he was experiencing significant anxiety as a result of having to adjust to the changes associated with his stroke. His difficulty appeared to be maintained by cognitive change affecting his vocational performance, his appraisal of his performance and his concerns for the future. It is likely his physical arousal also contributed to maintenance of his difficulties, providing him with a message that all was not well.

Measure

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety sub-scale (HADS-A, Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) is one of the few anxiety measures validated in a stroke population (Lincoln et al., 2012). While various cut offs in this population have been used, a score of 6 or more has been recommended for a community sample post-stroke (Kneebone, Neffgen, & Pettyfer, 2012; Sagen et al., 2009). The HADS also has a depression subscale and therefore is able to establish the presence absence of significant depressive symptoms.

Intervention

Ned was seen for seven sessions of 45–60 minutes in length, with treatment over a period of 3–4 months. The sessions were provided by a consultant clinical psychologist, listed on the Specialist Register of Clinical Neuropsychologists of the British Psychological Society, with over 20 years of experience working with people who have had a stroke. Intervention consisted of four major elements; psycho-education, relaxation training, cognitive disputation, and cognitive rehabilitation. The psycho-education involved considering with Ned the nature of the anxiety and its frequency post-stroke and developing his understanding of the formulation as noted above. Relaxation training was of the progressive muscle type (Winkler, James, Fatovich, & Underwood, 1982) and was chosen because Ned was a very active sportsman and it was considered this more physical strategy would fit with his background. Cognitive disputes considered coping self-statements for managing challenging moments and dealing with concerns for the future when they arose. Cognitive rehabilitation concentrated on strategies such as paraphrasing in order to slow down conversations and support information acquisition. Ned also prepared himself before answering the phone. For example, when he answered and asked, “Could you hold just one moment,” he could gather his thoughts and shift his attention. Ned was also encouraged to use a coping self-statement, “OK the anxiety is there but that is part of the deal now, if I relax I will absorb more of what they are telling me”. For homework Ned was instructed to practise the relaxation regularly and to trial the strategies developed within the cognitive therapy sessions.

Results

By session four Ned reported “feeling more normal” and described the cognitive strategies as “very useful”. He further reported he added strategies himself, “I stand up to take a phone call to get in business mode”. Ned further noticed that others had been impressed by his “more thoughtful responding”. No direct intervention for Ned's concerns about his financial circumstances proved necessary within the sessions. As Ned's anxiety reduced he became more accepting of his financial circumstances in that he felt he and his wife would manage although their retirement life style may not be as they had expected it would be, prior to the stroke.

Three months after the end of treatment, Ned reported his work days had increased from two hours a day, two days a week, to three hours a day, four days a week and that he was handling telephone calls much more easily. He also reported that he was waking up relaxed, with no “lump in his chest” or sensation of trembling. He also considered he was managing his worries.

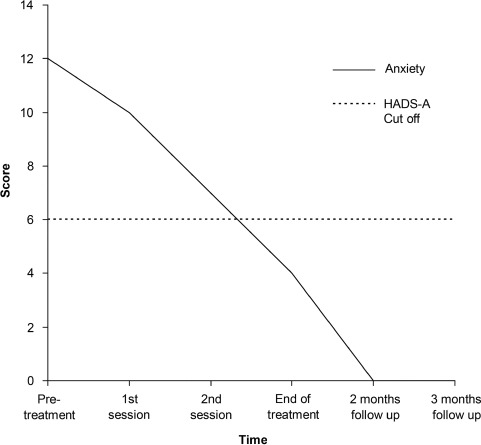

Figure 1 documents change on the HADS-A scale for Ned from pre-treatment to three month follow up. Over the course of treatment Ned's scores for anxiety reduced from well within the clinical range to well below it. This improvement was maintained at 2 and 3 month post-treatment follow ups. It should be noted that throughout the course of the contact with the psychologist Ned's scores on the depression subscale of the HADS remained subclinical.

Figure 1.

Change on the HADS-A (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety Sub-scale) for Ned from pre-treatment to three month follow up.

PARTICIPANT 2

Method

Participant

Myrtle (not her real name) was an 80-year-old retired nurse. Prior to her stroke, Myrtle was an active lady who socialised regularly and used public transport independently. Myrtle described herself as always having been “a worrier”. She also saw herself as a very independent lady who did not like to rely on others for help. Myrtle suffered a left middle cerebral artery infarct a year prior to the psychology referral. An MRI scan showed that the infarct involved the insular regions and the left temporal lobe, sparing the corpus striatum structures. The MRI scan also showed an old infarct in the right parietal region.

At the time of the stroke, Myrtle presented with right-sided weakness including right-sided facial weakness, dysphagia and no speech. She was admitted to hospital and thrombolysed. Sixteen days post-stroke, Myrtle was transferred to a rehabilitation ward. By this time, Myrtle had little residual physical disability and her main difficultly was dysphasia. She remained on the stroke rehabilitation ward, where she received physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy and medical care, for one month.

Myrtle did not appear to have long-term cognitive difficulties following the stroke: the Lowenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment completed by occupational therapists during her time on the rehabilitation ward demonstrated intact orientation, perception of objects and self, praxis and memory.

Myrtle was seen by a speech and language therapist (SALT) at acute and rehabilitation hospitals and subsequently as an outpatient. She received input for expressive dysphasia, which was described as “mild” by the time she was discharged from hospital. The SALT intervention focused on adopting a total communication approach (communicating in any way possible, including writing, drawing, gesturing, etc.) and reducing anxiety about her speech. After six sessions of outpatient SALT, Myrtle was referred to the psychology service for further work on anxiety about her speech.

At the time of the psychology referral, Myrtle had episodes of speech that were appropriate and intelligible, but at other times displayed disorganised language, reduced volume and “jargonistic” output. The SALT felt that this variability was directly related to anxiety and confidence. During a SALT session 11 months post-stroke, Myrtle rated her confidence as 1 out of 10 and reported avoiding situations that she used to enjoy, for example talking to friends and going to town.

Initial psychological assessment identified significant levels of anxiety. She reported worry about a stroke happening again, about finding it hard to communicate with others and about being a burden to family and friends. She scored 14 out of 20 on the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI), which is well above the cut off of 9 or more. Myrtle reported often feeling tearful and having a reduced appetite. She did not, however, report any difficulties with sleeping, nor did she report suicidal ideation. Her score on the Brief Assessment Schedule for Depression Cards (BASDEC) was below the cutoff (7 or more), indicating that Myrtle's main difficulties were principally related to anxiety. She believed that these difficulties had been triggered by the stroke and the resulting speech difficulties that this had left her with. Myrtle's goals of therapy were to: “Have more contact with family and friends,” “Visit sisters who lived between 30 and 60 miles away, using public transport independently,” “Visit family in her country of origin,” “Spend less time sitting on her own thinking about the things she worried about,” and “Return to hobbies she had previously enjoyed but currently avoided”.

Formulation

Myrtle appeared to be experiencing a high level of anxiety, including worry that she would have another stroke and that she was a burden to friends and family. She was also finding it hard and embarrassing to communicate with others and worrying on this account. The anxiety had resulted in Myrtle avoiding activities that she previously enjoyed, such as meeting friends, going bowling and going into town. The avoidance of these activities appeared to maintain her feelings of anxiety. Additionally, avoiding social activities resulted in a decrease in social contact, something which she had thoroughly enjoyed before her stroke and which was contributing to feelings of low mood and tearfulness. Due to her difficulties with communication, Myrtle relied more upon her family to help her with day-to-day activities. This decrease in control over her own life led to feelings of frustration and served to further maintain her high levels of anxiety.

Myrtle avoided talking to family members when she felt worried or upset, as in these emotional states she found it harder to speak coherently. This meant that at any time when she started to feel upset or worried, she would go upstairs and spend time on her own. This seemed to result in Myrtle's children worrying more about their mother. Myrtle's reluctance to discuss her anxieties with her family was also likely influenced by her independent nature and her reluctance to be “a burden” or to rely on others for help. Spending time on her own also resulted in increased time thinking about the possibility of having another stroke and what that might mean for her independence, thereby maintaining her difficulties.

Measures

There is currently no anxiety measure validated for use with older people after stroke (Kneebone et al., 2012). Given Myrtle's age and cognitive and communication difficulties it was considered inappropriate to administer the HADS-A which requires a choice of four response levels against a descriptive statement. Instead the GAI (Pachana et al., 2007) was used. This scale requires simpler Yes/No responses to statements. The GAI has been specifically developed for use with older people and research has shown it is reliable and valid in older people with another neurological condition, Parkinson's disease (Matheson et al., 2012). The standard cut off (a score of 9 or more) was used to consider the presence of significant anxiety symptoms.

To confirm the presence/absence of significant depressive symptoms, the BASDEC (Adshead, Cody, & Pitt, 1992) was used. The BASDEC was developed specifically for use with older people and has demonstrated good reliability and validity at its recommended cut off (7 or more) in sample with older people who have had a stroke (Healey, Kneebone, Carroll, & Anderson, 2008).

In addition to the standardised measures, one of Myrtle's major presenting concerns, the belief she would have another stroke that would render her completely unable to communicate, was also rated over the course of the intervention using a scale of 0 to 10 (“0” meaning believing this would definitely not happen, “10” meaning believing that this would certainly happen).

Intervention

Following the assessment session, eight sessions were held over an approximate four month period, followed by a one- and three-month follow up session. Sessions were 50–60 minutes in duration and administered by a trainee clinical psychologist, supervised by a consultant clinical psychologist as described under Participant 1.

Initial components of intervention included psycho-education about anxiety and the basis for cognitive-behavioural intervention. Following this, the focus was on relaxation training. This involved teaching breathing for relaxation and an autogenic relaxation exercise (Winkler et al., 1982), the script for which was recorded on a CD for Myrtle to take away and use at home.

Work then moved towards developing a hierarchy of situations that Myrtle was avoiding and working her way through confronting these situations. This was modified to accommodate Myrtle's difficulties with reading and writing. Hierarchies were not formally written down but noted by the therapist and discussed and updated in sessions. This style also served to maintain a collaborative therapeutic relationship and to avoid the therapist appearing didactic. Throughout the intervention, the therapist was careful to allow Myrtle to take the lead in sessions due to the lack of control that she found frustrating in other areas of her life. Cognitive disputation was undertaken while working through the hierarchy. Negative predictions associated with certain activities were challenged. For example, Myrtle avoided going to meet friends for coffee because she was concerned that she would have difficulty speaking and that this would result in her becoming extremely embarrassed and her friends becoming either impatient or pitying towards her. Once she had tested this out by going to meet friends, the evidence for these thoughts was revisited and updated. Myrtle was then able to identify strategies to use when she found it hard to speak clearly, for example taking a deep breath or asking for a moment to think.

The cognitive component of the work also involved disputing some of the beliefs that were contributing towards Myrtle's anxiety. One belief that was causing her a significant amount of distress was that she would definitely have another stroke and that this would render her completely unable to speak. This part of the intervention included psycho-education about stroke recurrence, the wide range of effects strokes can have, and risk factors for stroke. The risk of Myrtle having another stroke was real and acknowledged. However, discussions highlighted those things that Myrtle was already doing to minimise this risk (for example, not drinking alcohol, taking more exercise and using relaxation exercises and prescribed medication to lower blood pressure). The costs and benefits of worrying about something that she only had limited control over were also discussed. In order to support communication, discussions were summarised more frequently than might have been the case for a patient without deficits in this area. Additionally, discussions were revisited across sessions and important points summarised at the end of the session by the therapist when appropriate. Cognitive disputes were also kept as concrete as practical in light of Myrtle's communication problems, and behavioural components of the intervention emphasised. The therapist also wrote things down and slowed the pace of conversations to assist Myrtle's understanding.

The sixth session was used as a review session. At this point Myrtle had made progress towards her goals, including re-commencing a hobby, visiting family more frequently, using public transport to meet friends independently and finding that her speech was less frequently “muddled”.

Following the review, sessions focused on relapse prevention. This involved revisiting what Myrtle felt she had learnt over the course of therapy and what strategies she had used that would be helpful in future. These included continuing to practise relaxation and maintaining her current level of social activity. It was acknowledged that setbacks might occur, following which future challenges were identified and strategies to deal with these challenges were discussed. The cognitive-behavioural model was revisited, with specific focus on avoidance and its role in maintaining anxiety. Two follow-up sessions were held after one and then three months.

Results

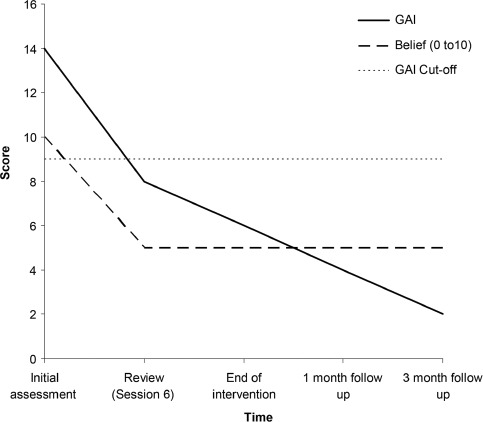

Figure 2 summarises the changes on the GAI, and the belief rating over the course of the intervention and at the two subsequent follow-up sessions. The positive change in scores was maintained over the course of therapy and at both follow up sessions. Myrtle's rating of her belief about having another stroke remained at 5 out of 10 from the review session onwards. When this was discussed, she explained that she was happy with this rating as she felt that it was “realistic” and reflected the real risk of stroke recurrence. Further, she felt that the anxiety associated with this belief had reduced significantly.

Figure 2.

Change on the GAI (Geriatric Anxiety Inventory) and the belief rating that she would have another stroke that would render her completely unable to communicate, for Myrtle from initial treatment to three month follow-up.

Other indicators of change included Myrtle's reports that she felt more confident going out on her own and more confident in her ability to communicate with other people and feeling “more like herself again”. She had also achieved many of her original therapy goals. Myrtle had re-engaged with previously enjoyed activities and more regularly met with friends. She made independent trips to see family members, including booking a holiday to see family in her country of origin who lived some distance away. Myrtle also reported that she felt she spent much less time “worrying about things” and was getting better at “taking each day as it comes”. Two follow-up sessions were held after one and then three months. Myrtle was offered a six month follow up session but declined the offer as she reported that she did not feel that another session was needed.

DISCUSSION

In two cases, cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy proved effective for anxiety unaccompanied by significant depression, after stroke. Both a working company director and a retired nurse demonstrated changes on formal measures of anxiety from the range of concern to sub-clinical levels, over relatively short courses of treatment. Consistent with recommendations (Broomfield et al., 2010; Hibbard et al., 1990; Lincoln et al., 2012) the treatment provided was modified in light of the disabilities evident in the therapy participants. In one case, cognitive rehabilitation strategies were incorporated, in the latter an emphasis was placed on behavioural strategies, more concrete disputation and frequent reviews in light of communication changes evident post-stroke and the age of the participant.

Further single case studies and case series of CBT for anxiety after stroke are required in order to develop a compendium of modifications to suit different presentations and thereby support clinicians’ treatment of particular patients. These case studies will have greater impact if they utilise more robust designs such as those with multiple baselines, more regular mood ratings and long-term follow up. They will also inform the development of manuals for future randomised controlled trials and help identify who is likely to benefit from modified CBT after stroke. If further research is not pursued there is a risk that treatment will not be offered to those affected, with implications for their coping and likely the rehabilitation outcomes that might be achieved. Studies should not only consider generalised anxiety syndrome but other anxieties that occur after stroke such as post-traumatic stress disorder (Bruggimann et al., 2006) and fear of falling (Watanabe, 2005). People with cognitive and communication difficulties present a challenge to the CBT therapist. The current paper indicates how these challenges can be overcome, when appropriate attention to disability is made, and supports further investigation.

REFERENCES

- Adshead F., Cody D. D., Pitt B. BASDEC: A novel screening instrument for depression in elderly medical in-patients. British Medical Journal. 1992;305:397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6850.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aström M. Generalised anxiety disorder in stroke patients. Stroke. 1996;27:270–276. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arundine A. M., Bradbury C. L. P., Dupuis K. M. A., Dawson D. R. P., Ruttan L. A. P., Green R. E. A. P. Cognitive behaviour therapy after acquired brain injury: Maintenance of therapeutic benefits at 6 months post treatment. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2012;27:104–112. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182125591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers C. R., Sorrell J. T., Thorp S. R., Wetherell J. L. Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychology & Ageing. 2007;22(1):8–17. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield N. M., Laidlaw K., Hickabottom E., Murray M. F., Pendrey R., Whittick J. E., Gillespie D. C. Post-stroke depression: The case for augmented, individually tailored cognitive behavioural therapy. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2010;18:202–217. doi: 10.1002/cpp.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury C. L., Christensen B. K., Lau M. A., Ruttan L. A., Arundine A. L., Green R. E. The efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of emotional distress after acquired brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89(12 Suppl):S61–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.08.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggimann L., Annoni J. M., Staub F., von Steinbuchel N., Van der Linden M., Bogous-slavsky J. Chronic posttraumatic stress symptoms after nonsevere stroke. Neurology. 2006;66:513–516. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194210.98757.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal F. J., Egido J. A. Quality of life after stroke: The importance of good recovery. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009;27:204–214. doi: 10.1159/000200461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Burton C. A., Holmes J., Murray J., Gillespie D., Lightbody C. E., Watkins C. L., Knapp P. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011. DOI: 10.1002/14658. CD008860.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Campbell Burton C. A., Murray J., Holmes J., Astin F., Greenwood D., Knapp P. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: A systematic review of observational studies. International Journal of Stroke. 2012. DOI: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.0096.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ferro J. M., Caeiro L., Santos C. Poststroke emotional and behaviour impairment: A narrative review. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009;27:197–203. doi: 10.1159/000200460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey A., Kneebone I., Carroll M., Anderson S. A preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of the Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards and the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen to screen for depression in older stroke survivors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23:531–536. doi: 10.1002/gps.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard M. R., Grober S., Gordon W. A., Aletta E. G. Modification of cognitive psychotherapy for the treatment of post-stroke depression. The Behavior Therapist. 1990;13:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson R. J., McDonald S., Tate R., Gertler P. A randomised controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioural therapy program for managing social anxiety after acquired brain injury. Brain Impairment. 2005;6:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kneebone I. I., Neffgen L., Pettyfer S. Screening for depression and anxiety after stroke: Developing protocols for use in the community. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2012;34:1114–1120. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.636137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniak M., Bak T., Czepiel W., Seniow J., Czlonkowska A. Frequency and prognostic value of cognitive disorders in stroke patients. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2008;26:356–363. doi: 10.1159/000162262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln N. B., Flannaghan T. Cognitive behavioural psychotherapy for depression following stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:111–115. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000044167.44670.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln N. B., Kneebone I. I., Macniven J. A. B., Morris R. Psychological management of stroke. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Matheson S. F., Byrne G. J., Dissanayaka N. N. W., Pachana N. A., Mellick G. D., O'Sullivan J. D., Silburn P. A., Sellbach A., Marsh R. Validity and reliability of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory in Parkinson's disease. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2012;31:13–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nys G., van Zandvoort M., De Kort P., Jansen B., De Haan E., Kappelle L. Cognitive disorders in acute stroke: Prevalence and clinical determinants. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2007;23:408–416. doi: 10.1159/000101464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachana N. A., Byrne G. J., Siddle H., Koloski N., Harley E., Arnold E. Development and validation of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory. International Psychogeriatrics. 2007;19:103–114. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagen U., Vik T. G., Moum T., Morland T., Finset A., Dammen T. Screening for anxiety and depression after stroke: Comparison of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. A., Walker M. F., Macniven J. A., Haworth H., Lincoln N. B. Communication and Low Mood (CALM): A randomized controlled trial of behaviour therapy for stroke patients with aphasia. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2013;27(5):398–408. doi: 10.1177/0269215512462227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade D. T., Langton Hewer R., David R. M., Enderby P. M. Aphasia after stroke: Natural history and associated deficits. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1986;49:11–16. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron B., Casserly L. M., O'Sullivan C. Cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety in adults with acquired brain injury. What works for whom? Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2012. DOI: 10.1080/09602011.2012.724196. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Watanabe Y. Fear of falling among stroke survivors after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2005;28:149–152. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R., Hill K., Hewison J., Knapp P., House A. Psychological disorders after stroke are an important influence on functional outcomes. A prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2010;41:1723–1727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler J., James R., Fatovich B., Underwood P. Migraine and tension headaches: A mulit-modal approach to the prevention and control of headache pain. University of Western Australia, The Self-Care Research Team; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]